Aggression

Introduction

Violence and aggression is recognized as a major hazard for staff within the healthcare sector (Chuo et al. 2012a). The fields of mental health, learning disability and emergency care, unsurprisingly, report the highest incidence of verbal and physical threats to staff (Health & Safety Commission Advisory 1997). The regular occurrence of violence within the NHS has been frequently documented (Crilly et al. 2004, Whittington & Winstanley 2008). A review of the management of work-related violence by the Royal College of Nursing (2008) suggested that the impact of work-related violence and aggression is not only physical in terms of injuries sustained by an individual, but can also result in psychological harm that may lead to stress, burn-out, anxiety and depression. These effects can, in turn, lead to a diminished job satisfaction, lower commitment to work and increasing levels of absence for the individual, which clearly impacts on the NHS as an organization.

While far from being the only area within the general hospital setting to see a rise in aggression and violence, the growing level of aggression witnessed within the emergency care setting is also well documented (Atawnehet et al. 2003, Crilly et al. 2004). Standing & Nicolini (1997) argued that the highest risks of violence at work are associated with:

• working with confused older people

• working with those who have mental health problems

In a study of the psychological impact of violence on staff, Hislop & Melby (2003) found that emergency nurses who had experienced violence in their departments expressed feelings of frustration, anger and fear as a result of this. The Scottish Government recognized the growing number of aggressive and violent incidents being perpetrated against emergency care staff, introducing new legislation, the Emergency Workers (Scotland) Act (2005) aimed at offering some protection for staff in this area. Although prevention of aggression and violence in the Emergency Department (ED) is the aim, it may not always be possible to stop this occurring. Aggression and violence in the ED develops as a result of a wide variety of factors, some of which can be identified and managed within the clinical setting. Others are unfortunately beyond the control of the emergency care staff; however, their awareness of these factors and the appropriate strategies to manage these issues is vital to maintain a safe environment for both staff and patients. This chapter will discuss the problem from these perspectives and offer some suggestions to assist the emergency nurse to resolve this increasing difficulty.

Assessing the problem

If staff are to attempt to resolve aggression in the ED, it is necessary to assess and manage the problem from a holistic and caring viewpoint, maintaining the safety and dignity of everyone involved. The ED can appear a very hostile and threatening place to a patient or relative in an emotionally charged state. Brennan (1998), in examining the range of theories of aggression and violence, suggested that providing satisfactory definitions or an explanation as to where or how these behaviours originate is a complex task.

From a psychological perspective the occurrence of a sudden crisis resulting from a serious illness or accident, with the hurried removal of an individual to an ED, can often trigger strong emotions (Hildegard et al. 1987). These emotions of fear, anxiety, confusion and loss of control often result in stress reactions within the patient or relative and can be displayed in a variety of ways, sometimes displayed as aggression. Many individuals view the ED as an anxiety-provoking and hostile environment. In these situations adrenaline (epinephrine) is released, and the classical ‘flight or fight’ response triggered. Freud (1932) argued that aggression was an innate, independent, instinctive tendency in humans. In contrast, Bandura (1973) identified the way in which children learn aggressive responses by role modelling what they had observed in adults. Bateson (1980) further argued that an individual is only aggressive when assessed in relation to the other people or surroundings affecting that individual. Dollard et al. (1939) suggested the hydraulic type model of aggression where he viewed the need to release built-up frustration as a natural event similar to that of a pressure cooker effect. The frustration of prolonged waiting times in ED can also trigger an aggression (Derlet & Richards 2000), however Crilly et al. (2004) found that 67% of patients who exhibited violent behaviour had been in the departments for less than 1 hour.

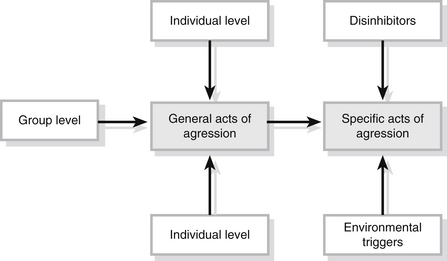

In reviewing the theories underpinning the development of aggression, Brewer (2007) identified a synthesis model of aggression within which the individual’s general level of aggression is determined by the combination of three types of factors; the individual, group and social (Fig. 12.1). In this model, physiological factors and neurochemical changes in the individual may combine with perceptions of other people’s behaviour to influence their response to an event or a situation. In this interpretation of factors that influence a person’s aggressive response, family or peer group views of acceptable levels of aggression or violence may also influence the individual’s response. Finally, this model acknowledges the impact of social factors such as the frequency of aggression portrayed on televions and the acceptability by society.

The major contribution made by physiological factors in the development of aggression in the ED has been identified as being the high consumption or withdrawal from alcohol or drugs (Jenkins et al. 1998). Intoxication with these drugs not only reduces the individual’s capacity to understand and interpret events, but also reduces inhibitory responses in times of stress. Violent incidents in the ED are more likely to occur within the hours of 00.00–07.00 with alcohol being identified as a major cause of violent behaviour (Schnieden & Marren-Bell 1995, Jenkins et al. 1998). Other organic reactions seen in acute confused states, e.g., metabolic disorders (diabetes or hypoxia resulting from respiratory or head injuries) or pain, may result in altered perceptions for the patient. These alterations in perception may also result in a confused aggressive patient arriving in the ED. When admitting these patients, the nurse may have to utilize very well-developed communication skills in order to make themself understood. In this condition the patient also may experience major problems in perceiving what is happening.

From an organizational viewpoint, the location of the ED, e.g., near to the public street, and 24-hour access may also attract a number of hostile individuals (Lyneham 2000). Distressed or psychologically disturbed patients often attend ED aware of the immediate access to medical and nursing care for crisis intervention. Their confused or distressed state may also result in aggressive responses to the ED staff. The ED itself can also influence the level of aggression displayed by patients and relatives who attend. The frustration that results from unrealistic expectations of the service may produce conflict and confrontation between the nurse and the patient or relative. Brewer (2007) suggests that the negative perceptions of the NHS often portrayed in the media may also impact upon the level of aggression demonstrated towards NHS staff. Lack of information and long waiting times for treatment as a result of poor staffing levels can also lead to frustration and anger (Jenkins et al. 1998). Poor waiting environments with lack of stimulation have also been suggested as being influential in developing aggression.

Further research suggests that less-experienced staff who demonstrated a more authoritarian attitude were potentially more at risk of assault (Breakwell & Rowett, 1989). Studies also identify that certain characteristics might be associated with some assaulted staff, which made them more prone to being assaulted (Lanza et al. 1991). The key element in all these studies is the nurse’s ability to communicate in a positive and caring manner with the patient or client. The importance of the nurse’s verbal and non-verbal communications with the patient or relative is demonstrated to be very important in conveying a caring, understanding attitude to an individual in times of stress or crisis, and in averting confrontation or aggression. It is acknowledged, however, that it may be difficult for the nurse to mask their underlying negative views on a patient and prevent negative non-verbal cues from being transmitted.

Identifying and recording the incidence of violence and aggression in the ED

Many authors suggest that aggressive incidents within healthcare and the ED are not recorded, and it is therefore difficult to measure the problem accurately (Forrester 2002, Pawlin 2008). This may be as a result of the lack of appropriate strategies and structures with which to recognize and record these incidents that occur all too regularly in ED. The Royal College of Nursing (2008) identifies a growing need for NHS staff to have access to the appropriate tools to identify the nature of the problem of violence and aggression in the workplace. They also recognize the lack of knowledge and information held by individuals, teams and organizations in relation to this issue, identifying a structure for risk assessments that should be undertaken to assess the problem. For staff, one of these risk assessments may require a review of the particular factors that influence aggression and violence in this particular environment, identifying practical measures within the emergency setting to address these factors.

Careful consideration of seating arrangements and decor of ED can help to reduce stress in those waiting to be treated. Other measures such as providing up-to-date reading material and a television or radio within the waiting area can reduce the boredom and frustration so often experienced while waiting in ED. The use of videos/DVDs explaining the organization of the ED or providing healthcare information can reduce tension and anxiety in the waiting area. These measures can also be employed to provide health promotion advice to the public. The provision of information is easily the most important issue to stressed relatives and friends, with other environmental factors also impacting on the level of anxiety and frustration experienced by the patient or relative (Box 12.1).

The increasing number of triage systems has been invaluable in improving the communication between the nurse and the public in the ED. During triage the patient can be assessed by the nurse and gain information with regard to their illness or injury and the expected waiting times. This initial assessment allows a relationship to be formed between the nurse and the patient and can provide an opportunity for the nurse to reduce the stress experienced by the patient. Access to the triage nurse keeps patients or relatives in constant communication with their progress through the department, further reducing stress and anxiety (Dolan 1998, Pich et al. 2011). The provision of adequate numbers of medical and nursing staff in the ED prevents long waiting times and allows good communication and the development of good patient–staff relationships. Less aggression is usually demonstrated if the patient or relative is satisfied with the level of care provided and good patient–staff relationships are formulated. This cannot occur in areas where patients and staff are under-resourced and under pressure. Dolan et al. (1997) found that the use of emergency nurse practitioners in the ED helped to reduce waiting times, assisting in a reduction in aggressive incidents at the times when nurse practitioners were on duty. In some inner city EDs it has been necessary, however, to provide increased security measures to limit the risk of aggression to staff. These measures have included the provision of security screens for reception staff, closed circuit security cameras, security guards, direct links to police stations via panic buttons and personal attack alarms (Cooke et al. 2000). Although these measures are not often conducive to conveying a caring, trusting attitude to the public, in some instances they have been required to protect the staff from injury.

Managing aggression in the ED

Managing aggression needs to be a planned and organized process. The nurse needs to have an awareness of the contributing factors in the development of aggression. In addition, the nurse must also have the ability to spot physical signs of impending aggression in order to measure the potential risk and manage it successfully. Aggressive outbursts rarely occur without warning and are almost always preceded by clear indications that the individual is becoming agitated or aggressive. Examination of behaviours immediately prior to an assault suggests that there are often ‘normal signs’ of impending aggression, both verbal and non-verbal, which if left to go unheeded may result in violent outbursts (Whittington & Patterson 1996). In the patient or relative, these signs include:

The ED nurse may not be the intended object of the aggressive individual’s outburst, but merely an obstacle in the path of the patient or a vehicle for releasing pent-up emotions. This, however, may be of little comfort to the nurse who experiences an aggressive outburst or who is injured by an agitated patient or relative. The nurse therefore has a responsibility to develop an awareness of the patient’s or relative’s emotional status through good communication, in order to prevent potentially aggressive incidents occurring.

Inexperience and lack of skill in some nurses in dealing with aggression may result in their avoidance of the agitated person until a violent situation occurs. Indeed, not all nurses are equipped or able to deal with aggressive or violent individuals. Defusing or de-escalating aggression is a complex process. Self-efficacy can be a major factor in the success of resolving an aggressive situation (Lee 2001). This perception of ourselves can help guide our behaviour and prevent escalation of an aggressive incident. Good verbal communication with the aggressive individual is vital in defusing the situation. A calm, confident non-threatening but assertive attempt to engage the individual in conversation is viewed as the first step to restoring order to the situation. This low-level approach to communication with the aggressor may prevent them from viewing the nurse as the aggressor. Lowe (1992) offers advice on how to manage the aggressive individual during this important stage:

• inform colleagues prior to your approach

• use confirming messages, expressing the person’s worth

• model personal control, and the ability to stay calm during the expression of anger and resentment towards you

• use honesty, expressing your feelings congruently

• if it is safe to do so, suggest a quieter area of the department

• set limits and clear guidelines that are consistently exerted

• use structure to let people know in advance what is expected of them

• monitor and learn to recognize patterns of behaviour

• timely and calmly intervene (de-escalation), helping the person to work through their anger, thereby breaking the aggressive cycle

• facilitate expression, allow people to express anger and fear somewhere safely

• use non-verbal skills, avoiding threat, and promoting calm and maintaining openness.

Encouraging the patient to discuss the problem may assist in defusing the tension of the moment. If the aggressive individual is confused or under the influence of alcohol or drugs, the nurse may have to repeat the message several times, before being understood. Intoxicated thinking often proceeds by association rather than logic. Key phrases such as ‘let us work together’ are recommended. Conversely, negative phrases such as ‘you’re not going to fight or give us trouble’ are generally inflammatory as the patient may associate with the words ‘fight’ and ‘trouble’ (Taylor & Ryrie 1996). Nothing will be gained by the nurse responding to the patient or relative negatively, despite the provocation from the aggressor. The nurse should listen carefully to the complaint and attempt to offer an explanation or agree a plan of action with the individual to resolve the situation. The use of solutions that are unachievable and the use of inaccurate information to pacify the individual are to be avoided. When these promises are not forthcoming, aggression is more likely. Self-awareness should also relate to the nurse taking appropriate measures to anticipate potential violence and initiate appropriate behaviours to avoid this.

Managing the violent individual

Managing the violent individual can be very distressing for staff and result in an acute crisis within the ED. As previously highlighted, many departments now employ security guards to assist in dealing with violent incidents and issue staff with personal attack alarms to reduce the risks to their person. This support is certainly useful to staff, but if a caring approach is to be adopted towards all individuals, the nurse cannot discharge the responsibility of managing the violent patient or relative to other colleagues. Learning to deal with this challenging and stressful situation is not easy. The appropriate knowledge and skills must result from a combination of role modelling of good management strategies and education (Paterson et al. 1999).

Whilst some question the use of physical restraint in patient care, Section 13.5 of the Code of Practice for the appropriate application of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (Public Guardians Office 2005) suggests that restraint is acceptable when it is: ‘Necessary to protect the person who lacks capacity from harm and in proportion to the likelihood and seriousness of that harm’.

• ensure that all staff are trained in crisis management

• remain calm and non-threatening in manner avoiding counter transference

• assess the person’s position and possible mode of attack – adjust response as necessary

• approach safely and gradually – do not be rushed

• move to a side-on position reducing exposure to assault and minimizing the appearance of threat

• one person should be responsible for verbal communication

• keep talking and negotiating on a non-physical alternative

• do not make promises or make offers which you cannot keep

• provide at least one face-saving opportunity

• the team should all be aware of the safe distance threshold

• if negotiation fails be decisive about reacting as a team

• when the individual is secured, move them to a resting position in a chair, to a trolley or on the floor

• allow the person time to relax

• ensure that only one team member communicates with the person

• use appropriate measures to screen the individual from the rest of the department maintaining dignity at all times

• when the individual is calm move to a quieter area with less stimulation.

The method of restraint will vary, depending on the incident. There are a variety of systems of physical intervention skills designed specifically for use in healthcare settings. It is strongly recommended that all staff that may be expected to implement restraint should be fully trained in carrying out these and other related procedures. In any type of restraint, it is essential that the individual being held is not compromised in their ability to breathe adequately. During restraint procedures, one team member must take responsibility for monitoring the individual’s airway, breathing and circulation. At no point in any restraint should pressure be applied to the throat, neck, chest, back or abdomen. Physical restraint should be used for the minimum amount of time required to control the situation, and the level of force used should be no greater than that required to achieve safety and control. This may include sedation or observation and counselling of the individual by staff. The decision to release the individual must be made by the team and carried out in a controlled, coordinated fashion to minimize the risk of injury to the violent individual and staff.

It is acknowledged that in extreme instances the degree of reasonable force necessary to control a violent individual may be of concern to the staff involved. In line with the requirement to treat people as individuals and respect their dignity highlighted in the Nursing and Midwifery Council (2008) Code of Conduct, the degree of force should be the minimum required to control the violence in a manner appropriate to calm rather than provoke further violence (Ferns 2005). Staff injured in the attempt to restrain the violent individual must also be reviewed by a doctor at the earliest opportunity and be made aware of their entitlement to criminal injuries compensation, if appropriate.

Follow-up care after an aggressive violent incident

In accordance with good professional practice, any aggressive or violent incidents should be reported to the senior nursing, medical and management teams and recorded appropriately within the documentation. In recognition of the growing levels of violence in the ED, most departments now require completion of an incident form specifically designed to record verbal or physical abuse of the staff. In making the report it is important to provide as much detail as possible about the circumstances of the incident. Pawlin (2008) reports the development of a data-recording tool used to capture incidences of violence and abuse directed towards staff in the ED. Analysis of this information may be useful in the prevention of further incidents, safeguarding future patients and staff. Box 12.2 identifies some of the information that should be documented following an aggressive or violent event.

In addition to the care of the aggressive individual, the nurse also has a responsibility for the psychological care of the staff and patients who may have been involved in or witnessed the incident. Distressed staff or patients/relatives should be afforded an opportunity to discuss their fears and anxieties arising from the incident, not least as one study found that nearly a third of post-violent incident reports indicated that there were no warning signs prior to the violent incidents (Chuo et al. 2012b). In some cases following extreme events, individuals involved in incidents of aggression or violence may require post-traumatic counselling. It is not a sign of weakness or failure for a nurse to admit the need for this support to overcome the trauma of such incidents. Critical incident stress debriefing should also be available for involved members of staff (Whitfield 1994) (see also Chapter 13).

Clearly, education in the risk factors that may lead to aggression and violence in the ED, the prevention and management of aggression, together with the skills in de-escalation strategies and breakaway techniques should violence occur, is vital for the nurse in the emergency care setting. In acknowledging this the Welsh Assembly Government (2004) has recently developed a new education programme for all NHS staff, the All Wales Violence and Aggression Training Passport and Information Scheme, designed to equip staff with the knowledge and skills to manage this problem (Box 12.3). This comprehensive programme will be available to all NHS staff and particularly aimed at the staff within the ED.

Conclusion

There should be a coordinated approach to dealing with aggression and violence in the ED, similar to the coordinated approach adopted in dealing with a critically ill patient or a cardiac arrest situation. Planning and resourcing for the prevention of aggression and violence in the ED should, therefore, be as detailed as the planning and resources provided for the prevention of death from cardiac arrest. For this to be achieved there must be a planned policy of response to a violent or aggressive outburst, which is known to all the staff within the department and practised on a regular basis. This policy should address key components such as a risk assessment, prevention strategies, training for staff, together with acceptable methods of managing violence and aggression (Hardin 2012).

References

Atawnehet, F.A., Zahid, M.A., AL-Sahlawi, K.S., et al. Violence against nurses in hospitals: Prevalence and effects. British Journal of Nursing. 2003;12(2):102–107.

Bandura, K. Aggression: A Social Learning Analysis. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hill; 1973.

Bateson, G. Mind and Nature. London: Fontana; 1980.

Breakwell, G., Rowett, C. Violence and social work. In: Archer J., Browne K., eds. Human Aggression Naturalistic Approaches. London: Routledge, 1989.

Brennan, W. Aggression and violence: Examining the theories. Emergency Nurse. 1998;6(2):18–21.

Brewer, K. Analysing aggression. Emergency Nurse. 2007;15(4):8–9.

Chuo, J.B., Magarey, J., Wiechula, R. Violence in the emergency department: An ethnographic study (part 1). International Emergency Nursing. 2012;20(2):69–75.

Chuo, J.B., Magarey, J., Wiechula, R. Violence in the emergency department: An ethnographic study (part 1). International Emergency Nursing. 2012;20(4):126–132.

Cooke, M.W., Higgins, J., Bridge, P. The Present State Emergency. In Medicine Research Group Warwick. University of Warwick; 2000.

Crilly, J., Chaboyer, W., Creedy, D. Violence towards emergency department nurses and patients. Accident and Emergency Nursing. 2004;12:67–73.

Derlet, R.W., Richards, J.R. Overcrowding in the nation’s emergency departments: Complex causes and disturbing effects. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2000;35(1):63–68.

Dolan, B. Waiting times (Editorial). Emergency Nurse. 1998;6(4):1.

Dolan, B., Dale, J., Morley, V. Nurse practitioners: Role in A&E and primary care. Nursing Standard. 1997;11(17):33–38.

Dollard, J., Doob, L.W., Miller, N.E., et al. Frustration and Aggression. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press; 1939.

Emergency Workers (Scotland) Act 2005. Edinburgh, Scottish Parliament.

Ferns, T. Terminology, stereotypes and aggression dynamics in the accident and emergency department. Accident and Emergency Nursing. 2005;13(4):238–246.

Forrester, K. Aggressions and assault against nurse in the workplace: Practice and legal issues. Journal of Law and Medicine. 2002;9(4):386–391.

Freud, S. The Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. London: Hogarth Press; 1932.

Hardin, D. Strategies for nurse leaders to address aggressive and violent events. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2012;42(1):5–8.

Health & Safety Commission Advisory. Committee on Violence and Aggression to Staff in the Health Services. London: HSE Books; 1997.

Hildegard, E.R., Hildegard, R., Atkinson, R.C. Introduction to Psychology. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; 1987.

Hislop, E., Melby, V. The lived experience of violence in accident and emergency. Accident and Emergency Nursing. 2003;11(1):5–11.

Jenkins, M.G., Rocke, L.G., McNicholl, B.P., et al. Violence and verbal abuse against staff in A&E departments: Survey of consultants in the UK and the Republic of Ireland. Journal of Accident and Emergency Medicine. 1998;15(4):262–265.

Lanza, M.L., Kayne, H.L.C., Hicks, C., et al. Nursing staff characteristics related to patients assault. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 1991;12(3):253–265.

Lee, F. Violence in A&E: The role of training in self-efficacy. Nursing Standard. 2001;15(46):33–38.

Lowe, T. Characteristics of effective nursing interventions in the management of challenging behaviour. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1992;17:1226–1232.

Lyneham, J. Violence in New South Wales emergency departments. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2000;18:8–17.

Nursing and Midwifery Council. The Code: Standards of Conduct Performance and Ethics for Nurses and Midwives. London: NMC; 2008.

Paterson, B., McCormish, A.G., Bradley, P. Violence at work. Nursing Standard. 1999;13(21):43–46.

Pawlin, S. Reporting violence. Emergency Nurse. 2008;16(4):16–21.

Pich, J., Hazelton, M., Sundin, D., et al. Patient-related violence at triage: A qualitative descriptive study. International Emergency Nursing. 2011;19:12–19.

Public Guardians Office. Code of Practice for the Appropriate Application of the Mental Capacity Act 2005. London: PGO; 2005.

Royal College of Nursing. Work-related Violence: an RCN Tool to Manage Risk and Promote Safer Working Practices in Health Care. London: RCN; 2008.

Schnieden, V., Marren-Bell, U. Violence in the A&E department. Accident and Emergency Nursing. 1995;3(2):74–78.

Standing, H., Nicolini, D. Review of Workplace Related Violence. London: HSE Books; 1997.

Taylor, R., Ryrie, I. Chronic alcohol users in A&E. Emergency Nurse. 1996;4(3):6–8.

Welsh Assembly Government. All Wales Violence and Aggression Training Passport and Information Scheme. Cardiff: WAG; 2004.

Whitfield, A. Critical incident debriefing in A&E. Emergency Nurse. 1994;2(3):6–9.

Whittington, R., Patterson, P. Verbal and non-verbal behaviour immediately prior to aggression by mentally disordered people: enhancing risk assessment. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 1996;3:47–54.

Whittington, R., Winstanley, R. Commentary on Luck L, Jackson D, Usher K (2008) Innocent or culpable? Meanings that ED nurses ascribe to individual acts of violence. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2008;17(16):2235–2237.