Chapter 145 Adverse Reactions to Foods

Adverse reactions to foods consist of any untoward reaction following the ingestion of a food or food additive and are classically divided into food intolerances, which are adverse physiologic responses, and food hypersensitivities, which include adverse immunologic responses and allergies (Tables 145-1 to 145-3). Like other atopic disorders, food allergies have increased over the past 3 decades, primarily in “Westernized” countries, and now affect an estimated 3.5% of the U.S. population. Up to 6% of children experience food allergic reactions in the 1st 3 yr of life, including about 2.5% with cow’s milk allergy, 1.5% with egg allergy, and 1% with peanut allergy. Most children “outgrow” milk and egg allergies, with about 50% doing so within 3-5 yr. In contrast, about 80-90% of children with peanut, nut, or seafood allergy retain their allergy for life.

Table 145-1 ADVERSE FOOD REACTIONS

FOOD INTOLERANCE

Host Factors

Enzyme deficiencies—lactase (primary or secondary), fructase (maturational delay)

Gastrointestinal disorders—inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome

Idiosyncratic reactions—caffeine in soft drinks (“hyperactivity”)

Psychologic—food phobias

Migraines (rare)

Food Factors

Infectious organisms—Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Clostridium

Toxins—histamine (scombroid poisoning), saxitoxin (shellfish)

Pharmacologic agents—caffeine, theobromine (chocolate, tea), tryptamine (tomatoes), tyramine (cheese)

Contaminants—heavy metals, pesticides, antibiotics

FOOD HYPERSENSITIVITIES

IgE-Mediated

Cutaneous—urticaria, angioedema, morbilliform rashes, flushing, contact urticaria

Gastrointestinal—oral allergy syndrome, gastrointestinal anaphylaxis

Respiratory—acute rhinoconjunctivitis, bronchospasm

Generalized—anaphylactic shock, exercise induced anaphylaxis

Mixed IgE- and Cell-Mediated

Cutaneous—atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis

Gastrointestinal—allergic eosinophilic esophagitis and gastroenteritis

Respiratory—asthma

Cell Mediated

Cutaneous—contact dermatitis, dermatitis herpetiformis

Gastrointestinal—food protein–induced enterocolitis, proctocolitis, and enteropathy syndromes, celiac disease

Respiratory—food-induced pulmonary hemosiderosis (Heiner syndrome)

Unclassified

Cow’s milk–induced anemia

IgE, immunoglobulin E.

Table 145-2 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF ADVERSE FOOD REACTIONS

GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS (WITH VOMITING AND/OR DIARRHEA)

Structural abnormalities (pyloric stenosis, Hirschsprung disease)

Enzyme deficiencies (primary or secondary):

Disaccharidase deficiency—lactase, fructase, sucrase-isomaltase

Galactosemia

Malignancy with obstruction

Other: pancreatic insufficiency (cystic fibrosis), peptic disease

CONTAMINANTS AND ADDITIVES

Flavorings and preservatives—rarely cause symptoms:

Sodium metabisulfite, monosodium glutamate, nitrites

Dyes and colorings—very rarely cause symptoms (urticaria, eczema):

Tartrazine

Toxins:

Bacterial, fungal (aflatoxin), fish-related (scombroid, ciguatera)

Infectious organisms:

Bacteria (Salmonella, Escherichia coli, Shigella)

Virus (rotavirus, enterovirus)

Parasites (Giardia, Akis simplex [in fish])

Accidental contaminants:

Heavy metals, pesticides

Pharmacologic agents:

Caffeine, glycosidal alkaloid solanine (potato spuds), histamine (fish), serotonin (banana, tomato), tryptamine (tomato), tyramine (cheese)

PSYCHOLOGIC REACTIONS

Food phobias

Etiology

Adverse reactions to foods may result from intolerances, which are based on functional properties of foods, or from physiologic responses of the host, including hypersensitivities and adverse immunologic responses (see Table 145-1). Although food represents the largest antigenic load confronting the body, the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) is able to readily discriminate between “harmless” foods and pathogenic organisms. Ingestion of food normally leads to oral tolerance, which is the induction of T-cell anergy and T regulatory cells that enable the systemic immune system to “ignore” the roughly 2% of antigenic protein normally entering the systemic circulation at each meal. In young infants, functional barriers (stomach acidity, intestinal enzymes, glycocalyx) and immunologic barriers (secretory immunoglobulin [Ig] A) are immature, allowing increased penetration of food antigens, and the GALT appears less capable of “tolerizing” than the mature system. Consequently, food hypersensitivity reactions most commonly develop at this susceptible age.

Pathogenesis

Children in whom IgE-mediated food allergies develop may be sensitized by food allergens penetrating the gastrointestinal barrier, which are class 1 food allergens, or by partially homologous allergens such as plant pollens penetrating the respiratory tract, which are class 2 food allergens. Any food may serve as a class 1 food allergen, but egg, milk, peanuts, tree nuts, fish, soy, and wheat account for 90% of food allergies during childhood. Many of the major allergenic proteins of these foods have been characterized. There is variable but significant cross reactivity with other proteins within an individual food group. Exposure and sensitization to these proteins often occur very early in life, because intact food proteins are passed to the infant through maternal breast milk, and after introduction of solid foods, many parents strive to provide their infants with a highly varied diet. Virtually all milk allergies develop by 12 mo of age and all egg allergies by 18 mo of age, and the median age of 1st peanut allergic reactions is 14 mo. Class 2 food allergens are typically plant or fruit proteins that are partially homologous with pollen proteins (see Table 145-3). With the development of seasonal allergic rhinitis from birch, grass, or ragweed pollens, subsequent ingestion of certain uncooked fruits or vegetables provokes the oral allergy syndrome. Intermittent ingestion of allergenic foods may lead to acute symptoms, whereas prolonged exposure may lead to chronic disorders such as atopic dermatitis and asthma. Cell-mediated sensitivity typically develops to class 1 allergens.

Clinical Manifestations

From a clinical and diagnostic standpoint, it is most useful to subdivide food hypersensitivity disorders according to the predominant target organ and immune mechanism (see Table 145-1).

Gastrointestinal Manifestations

Food protein–induced enteropathy often manifests in the 1st several months of life as diarrhea, not infrequently steatorrhea, and poor weight gain. Symptoms include protracted diarrhea, vomiting in up to 65% of cases, failure to thrive, abdominal distention, early satiety, and malabsorption. Anemia, edema, and hypoproteinemia occur occasionally. Cow’s milk sensitivity is the most common cause of this food protein–induced enteropathy in young infants, but it has also been associated with sensitivity to soy, egg, wheat, rice, chicken, and fish in older children. Celiac disease, the most severe form of protein-induced enteropathy, occurs in 1 : 100-1 : 250 of the U.S. population, although it may be “silent” in many patients (Chapter 330.2). The full-blown form is characterized by extensive loss of absorptive villi and hyperplasia of the crypts, leading to malabsorption, chronic diarrhea, steatorrhea, abdominal distention, flatulence, and weight loss or failure to thrive. Oral ulcers and other extraintestinal symptoms secondary to malabsorption are not uncommon. Genetically susceptible individuals (HLA-DQ2 or DQ8) demonstrate a cell-mediated response to tissue transglutaminase (tTGase) deamidated gliadin, which is found in wheat, rye, and barley.

Skin Manifestations

Cutaneous food allergies are also common in infants and young children.

Atopic dermatitis is a form of eczema that generally begins in early infancy and is characterized by pruritus, a chronically relapsing course, and association with asthma and allergic rhinitis (Chapter 139). Although not often apparent from history, at least 30% of children with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis have food allergies. The younger the child and the more severe the eczema, the more likely food allergy is playing a pathogenic role in the disorder.

Acute urticaria and angioedema are among the most common symptoms of food allergic reactions (Chapter 142). The onset of symptoms may be very rapid, within minutes after ingestion of the responsible allergen. Symptoms result from activation of IgE-bearing mast cells by circulating food allergens that are absorbed and circulated rapidly throughout the body. Foods most commonly incriminated in children include egg, milk, peanuts, and nuts, although reactions to various seeds (sesame, poppy) and fruits (kiwi) are becoming more common. Chronic urticaria and angioedema are rarely due to food allergies.

Respiratory Manifestations

Food allergic reactions are the single most common cause of anaphylaxis seen in hospital emergency departments. In addition to the rapid onset of cutaneous, respiratory, and gastrointestinal symptoms, patients may demonstrate cardiovascular symptoms, including hypotension, vascular collapse, and cardiac dysrhythmias, which are presumably caused by massive mast cell–mediator release. Food-associated exercise-induced anaphylaxis occurs more frequently among teenage athletes, especially females (Chapter 143).

Diagnosis

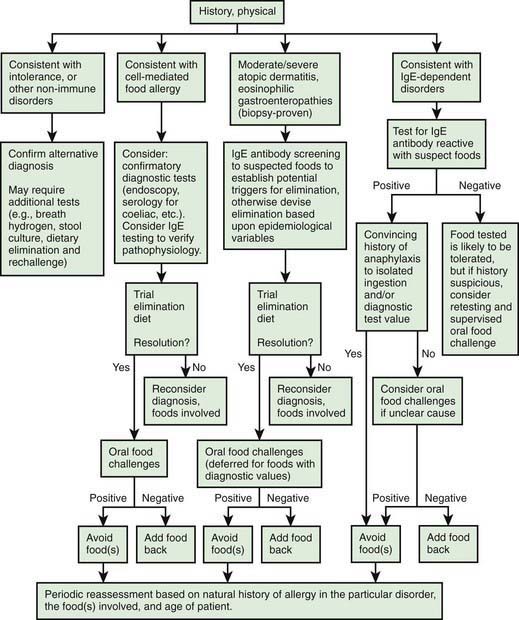

A thorough medical history is necessary to determine whether a patient’s symptomatology represents an adverse reaction (see Table 145-2), whether the adverse food reaction is an intolerance or hypersensitivity reaction, and if the latter, whether it is likely to be an IgE-mediated or a cell-mediated response (Fig. 145-1). The following facts should be established: (1) the food suspected of provoking the reaction and the quantity ingested, (2) the interval between ingestion and the development of symptoms, (3) the types of symptoms elicited by the ingestion, (4) whether ingesting the suspected food produced similar symptoms on other occasions, (5) whether other inciting factors, such as exercise, are necessary, and (6) the interval from the last reaction to the food.

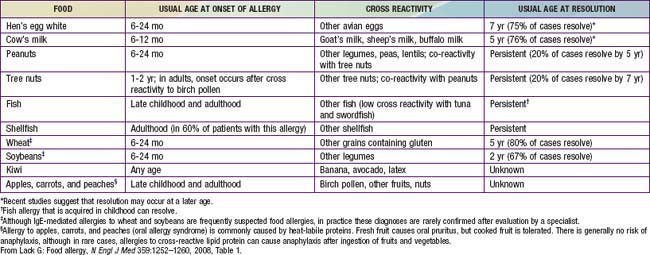

Figure 145-1 General scheme for diagnosis of food allergy.

(From Sicherer SH: Food allergy, Lancet 360:701–710, 2002.)

Prick skin tests and in vitro laboratory tests are useful for demonstrating IgE sensitization. Many fruits and vegetables require testing with fresh produce because labile proteins are destroyed during commercial preparation. A negative skin test result virtually excludes an IgE-mediated form of food allergy. Conversely, the majority of children with positive skin test responses to a food do not react when the food is ingested, so more definitive tests, such as quantitative IgE tests or food elimination and challenge, are often necessary to establish a diagnosis of food allergy. Serum food-specific IgE levels ≥15 kUA/L for milk (≥5 kUA/L for children ≤1 yr), ≥7 kUA/L for egg (≥2 kUA/L for children <3 yr), and ≥14 kUA/L for peanut are associated with a >95% likelihood of clinical reactivity to these foods in children with suspected reactivity. In the absence of a clear history of reactivity to a food and evidence of food-specific IgE antibodies, definitive studies must be performed before recommendations are made for avoidance or the use of highly restrictive diets that may be nutritionally deficient, logistically impractical, disruptive to the family, and a potential source of future feeding disorders. IgE-mediated food allergic reactions are generally very food specific, so the use of broad exclusionary diets, such as avoidance of all legumes, cereal grains, or animal products, is not warranted (Tables 145-3 and 145-4).

Table 145-4 CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS OF CROSS-REACTIVE PROTEINS IN IMMUNOGLOBULIN E–MEDIATED ALLERGY

| FOOD FAMILY | RISK OF ALLERGY TO ≥ 1 MEMBER (%; APPROXIMATE) | FEATURE(S) |

|---|---|---|

| Legumes | 5 | Main causes of reactions are peanut, soya, lentil, lupine, and garbanzo |

| Tree nuts (e.g., hazel, walnut, brazil) | 35 | Reactions are often severe |

| Fish | 50 | Reactions can be severe |

| Shellfish | 75 | Reactions can be severe |

| Grains | 20 | |

| Mammalian milks | 90 | Cow’s milk is highly cross reactive with goat’s or sheep’s milk (92%) but not with mare’s milk (4%) |

| Rosaceae (rock) fruits | 55 | Risk of reactions to more than three related foods is very low (<10%) |

| Latex-food | 35 | For individuals allergic to latex, banana, kiwi, and avocado are the main causes of reactions |

From Sicherer SH: Food allergy, Lancet 360:701–710, 2002.

Treatment

Appropriate identification and elimination of foods responsible for food hypersensitivity reactions are the only validated treatments for food allergies. Complete elimination of common foods (milk, egg, soy, wheat, rice, chicken, fish, peanut, nuts) is very difficult because of their widespread use in a variety of processed foods. The Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network (www.foodallergy.org or 800-929-4040) provides excellent information to help parents deal with both the practical and emotional issues surrounding these diets. Children with asthma and IgE-mediated food allergy, peanut or nut allergy, or a history of a previous severe reaction should be given self-injectable epinephrine (EpiPen) and a written emergency plan in case of accidental ingestion (Chapter 143). Because many food allergies are outgrown, arrangements should be made to have children reevaluated periodically by an allergist to determine whether they have lost their clinical reactivity. A number of clinical trials are under way, evaluating the use of oral immunotherapy and sublingual immunotherapy for the treatment of IgE-mediated food allergies (milk, egg, peanut). In addition, other forms of therapy, such as anti-IgE immunoglobulin therapy, engineered recombinant food protein vaccines, and herbal formulations, are being evaluated and may provide more definitive means of treating food allergies or at least raising the threshold for adverse reactions. In addition, tolerance may be generated by heating (cooking) the food (milk).

Angier E, Sheikh A. Pollen food syndrome in a teenage student. BMJ. 2010;340:b3405.

Baldassarre ME, Laforgia N, Fanelli M, et al. Lactobacillus GG improves recovery in infants with blood in the stools and presumptive allergic colitis compared with extensively hydrolyzed formula alone. J Pediatr. 2010;156:397-401.

Battista Pajno G, Caminiti L, Ruggeri P, et al. Oral immunotherapy for cow’s milk allergy with a weekly up-dosing regimen: a randomized single-blind controlled study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105:376-381.

Bischoff SC, Crowe S. Gastrointestinal food allergy: new insights into pathophysiology and clinical perspectives. Gastroenterol. 2005;128:1089-1113.

Bock SA, Munoz-Furlong A, Sampson HA. Further fatalities caused by anaphylactic reactions to food, 2001–2006. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:1016-1018.

Boyce JA, Assa’ad A, Burks AW, et al. Guideline for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the United States: report of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(6):S1-S58.

Burks AW. Peanut allergy. Lancet. 2008;371:1538-1546.

Chapman JA, Bernstein IL, Lee RE, et al. Food allergy: a practice parameter. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;96:S1-S68.

Du Toit G, Katz Y, Sasieni P, et al. Early consumption of peanuts in infancy is associated with a low prevalence of peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:984-991.

Fleischer DM, Conover-Walker MK, Matsui EC, et al. The natural history of tree nut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:1087-1093.

Green TD, LaBelle VS, Steele PH, et al. Clinical characteristics of peanut-allergic children: recent changes. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1304-1310.

Greer FR, Sicherer SH, Burks AW. Effects of early nutritional interventions on the development of atopic disease in infants and children: the role of maternal dietary restriction, breastfeeding, timing of introduction of complementary foods, and hydrolyzed formulas. Pediatrics. 2008;121:183-191.

Lack G. Epidemiological risk factors for food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:1331-1336.

Lack G. Food allergy. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1252-1260.

Longo G, Barbi E, Berti I, et al. Specific oral tolerance induction in children with very severe cow’s milk-induced reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:343-347.

Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Bloom KA, Sicherer SH, et al. Tolerance to extensively heated milk in children with cow’s milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:343-347.

Nwaru BI, Erkkola M, Ahonen S, et al. Age at introduction of solid foods during the first year and allergic sensitization at age 5 years. Pediatrics. 2010;125:50-59.

Pratt CA, Demain JG, Rathkopg MM. Food allergy and eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders: guiding our diagnosis and treatment. Curr Prob Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2008;38:165-196.

Rudders SA, Banerji A, Clark S, et al. Age-related differences in the clinical presentation of food-induced anaphylaxis. J Pediatr. 2011;158:326-328.

Sackeyflo A, Senthinathan A, Kandaswamy P, et al. Diagnosis and assessment of food allergy in children and young people: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2011;342:544-546.

Sampson HA. Food allergy—accurately identifying clinical reactivity. Allergy. 2005;60(Suppl 79):19-24.

Schneider Chafen JJ, Newberry SJ, Riedl MA, et al. Diagnosing and managing common food allergies. JAMA. 2010;303(18):1848-1856.

Sheikh A, Venderbosch I, Nurmatov U. Oral immunotherapy for peanut allergy. BMJ. 2010;341:264.

Sicherer SH, Mahr T, Section on Allergy and Immunology. Clinical report—management of food allergy in the school setting. and the. Pediatrics. 2010;126:1232-1239.

Sicherer SH, Sampson HA. Food allergy: recent advances in pathophysiology and treatment. Ann Rev Med. 2009;60:261-278.

Sicherer SH, Sampson HA. Peanut allergy: Emerging concepts and approaches for an apparent epidemic. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:491-503.

Skripak JM, Nash SD, Rowley H, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of milk oral immunotherapy for cow’s milk allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:1154-1160.

Townley RG. Is sublingual immunotherapy “ready for prime time”. Chest. 2008;133:589-590.