Chapter 4 Advancement Flaps

FLAP DESIGN AND CONSIDERATIONS

Aulius Cornelius Celsus wrote his 21-volume medical textbook, De Re Medicina Libri Octi, almost 2000 years ago. In it he described a method for repairing “mutilations” of the ear, lips, and nose that is still in use today, the advancement flap:

The method of treatment is as follows: the mutilation is enclosed in a square; from the inner angles of this, incisions are made across, so that the part on one side of the quadrilateral is completely separated from that on the opposite side. Then the two flaps, which have been freed are brought together.1

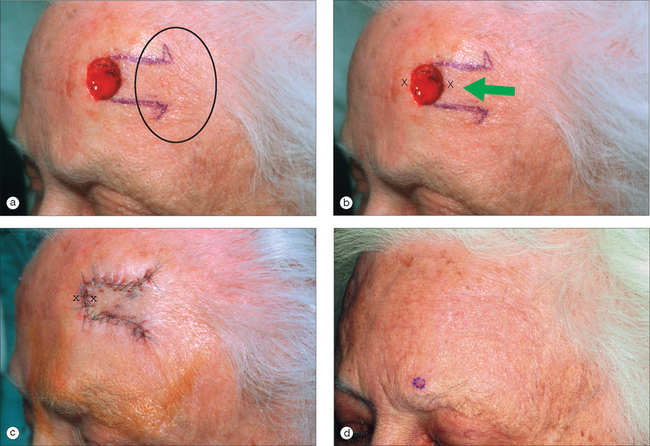

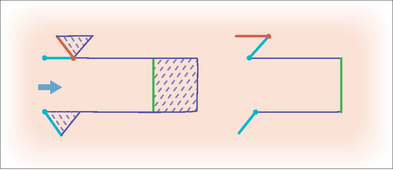

Clearly not a recent innovation, the advancement flap can be thought of as a sliding flap that moves along a single vector directly into the surgical defect (Figure 4.1). Once the defect is closed, the surrounding tissue provides the secondary movement or opposing force.2 The flap is designed by extending parallel incisions (not necessarily of the same length) from one side of a surgical defect. Since the flap is created from adjacent skin, one edge of the defect becomes the advancing tip of the flap. This basic design has also been called a U-plasty or rectangular flap. The prominent horizontal lines make the advancement flap particularly useful in the reconstruction of the eyebrow and forehead areas. It can also be effective for reconstruction of defects on the upper lip, dorsal nose, and helical rim.

The primary advantage of an advancement flap lies in its ability to redistribute standing cones (dog-ears) to a more favorable location that is not necessarily contiguous with the defect. When a circular wound is closed with a linear side-to-side closure, standing cones develop adjacent to the superior and inferior apices. In both rotation and transposition flaps, a standing cone develops at the pivotal base where it must be excised to allow for full movement of the flap.3 The geometry of an advancement flap allows for excision of tissue redundancy anywhere along the length of the flap. In this way the incisions can be hidden within relaxed skin tension lines (RSTLs) or cosmetic unit junction lines (Figure 4.2).

There are several factors that must be taken into account when designing an advancement flap. The most important consideration is the amount of tissue laxity available for closure of the defect. An advancement flap does not lower the tension of closure much beyond that which can be achieved with a side-to-side closure and it is not a good choice for large defects without surrounding laxity. With experience, the surgeon can estimate the degree of tissue mobility and identify tissue reservoirs by pinching and stretching the defect and surrounding skin. The physical manipulation of tissue to estimate mobility cannot be stressed enough. Once the flap is incised from the surrounding tissue, it relies on the blood supply within its pedicle to maintain viability. The flap’s perfusion is determined largely by its dimensions, the quality of the vasculature within its pedicle, and the tension placed upon it during closure.4 Blood flow to the tip of the flap is inversely related to the tension of wound closure and even a wide, well-perfused flap is at risk for necrosis if placed under too much strain.5

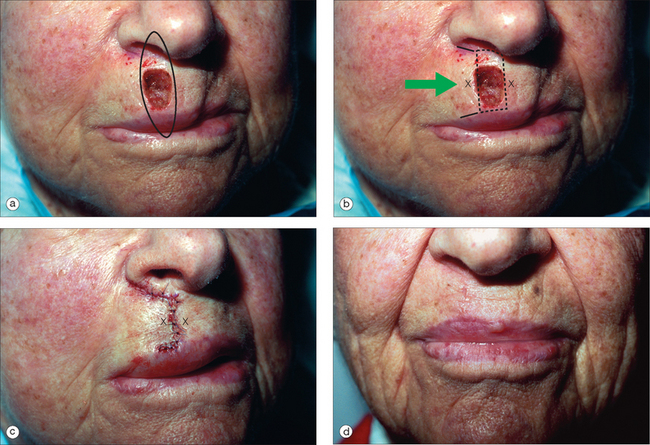

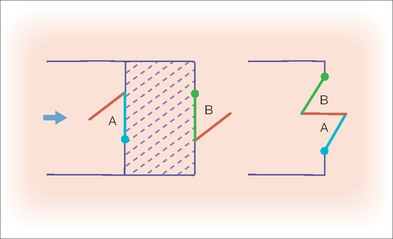

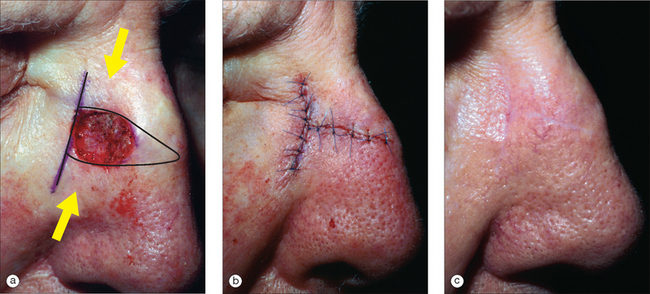

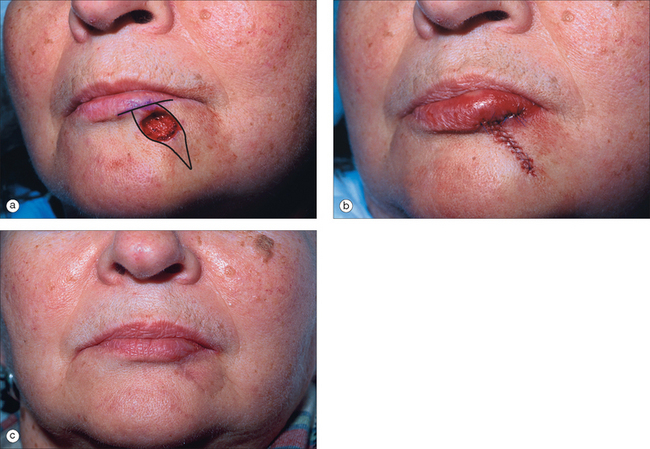

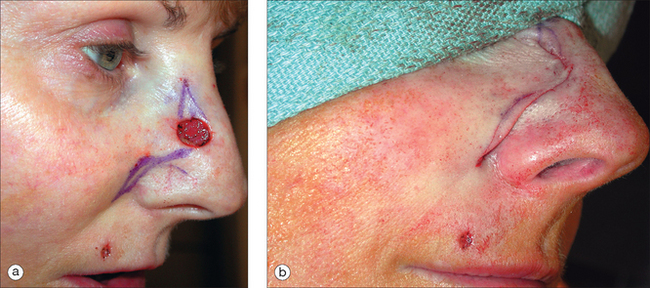

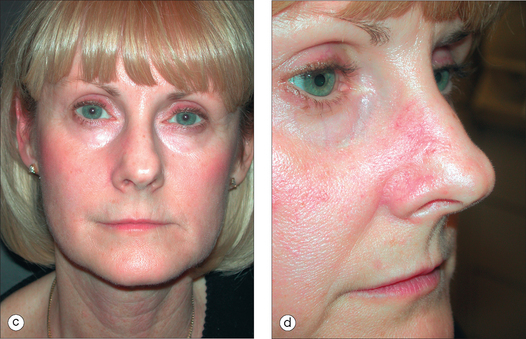

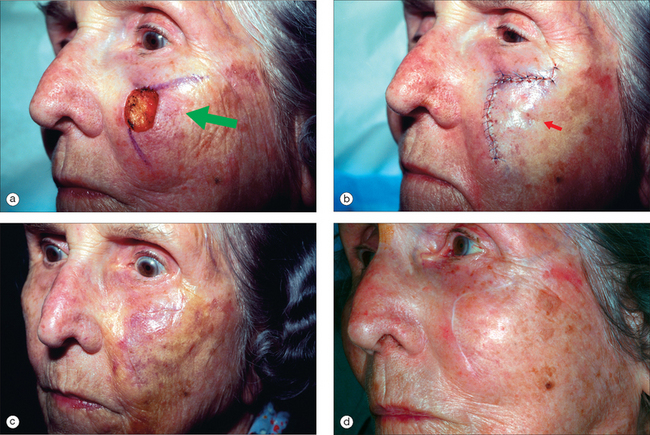

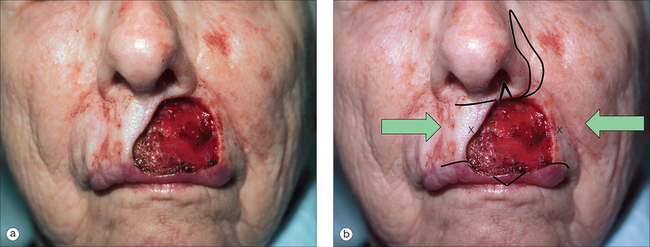

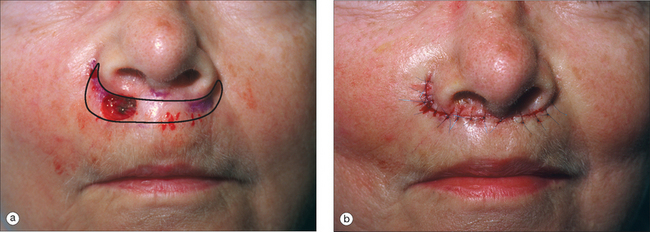

Figure 4.3 demonstrates some of the fundamental considerations of flap design, which include sufficient tissue laxity to allow for tension-free closure, no distortion of free margins, placement of incision lines in cosmetic junction lines, and reliable flap perfusion. In this case, by pinching the defect and surrounding skin, the surgeon was able to identify the melolabial fold as an available tissue reservoir and the lip as the free margin at highest risk for distortion. There was sufficient laxity to permit a horizontal side-to-side closure but this would have created standing cones that extended into the nostril and across the vermilion. Instead, an advancement flap that displaced the standing cones laterally instead of vertically was designed. The tension vector was oriented parallel to the free margin of the lip to minimize any distortion. The flap had a wide, tension-free pedicle that increased the likelihood of an adequate blood supply. Of note is that the defect was enlarged slightly to allow for placement of the incisions along cosmetic junction lines. Generally, the width of an advancement flap is determined by the height of the defect but in select circumstances, the surgeon may consider widening the defect to allow for better camouflage of incision lines and a more aesthetic outcome.6 If desired, a Z-plasty may be incorporated into the leading edge of the advancement flap to further decrease the risk for upward pull on the lip with scar contraction (Figure 4.4). This modification not only widens the flap tip, but also breaks up and partially redirects the scar line along which some contraction will occur during wound healing.

FLAP MOBILIZATION AND KEY SUTURES

Once the flap design has been determined, the proposed incision lines should be marked on the skin prior to infiltrating additional local anesthesia. This allows for more accurate placement without distortion by tumescence. To ensure symmetry, these markings should be confirmed with the patient in the upright position. After local anesthesia is achieved, the surgical defect may be undermined in all directions prior to incising the flap. This allows the surgeon to assess the degree of tissue laxity and to reconfirm the surgical plan. It is wise to approach each reconstruction with several alternatives in mind, recognizing that intraoperative adjustments in the surgical plan may be necessary. For example, there are times when unexpected laxity may allow for a less complex closure with comparable cosmesis and lower morbidity. Conversely, there may be less movement than expected requiring flap modification. The potential for either scenario always exists and it is best to have considered all potential outcomes before starting any surgical procedure. It is usually helpful to make incisions that keep the most options available first, and save those that lock into a particular closure for last.

The classic advancement flap is designed for a rectangular defect but it is not always necessary to square the edges of a circular defect prior to incising the flap.7 In fact, it may be prudent to wait until the flap has been mobilized to evaluate whether the recipient defect should be modified or the flap tip rounded. Since flap viability is directly related to the width of the pedicle and not the shape of the flap distal to it, the surgeon is free to choose the option that achieves the best aesthetic result.4

The final length of the flap will depend upon the width of the pedicle, anatomic location of the defect, and adjacent skin laxity. In general, the maximum length for a random pattern flap on the face is limited to 3–4 times the width of the pedicle.8 The surgeon may consider making the initial incisions slightly shorter than were originally designed to accommodate unexpected laxity discovered after undermining. These incisions can always be extended if additional length is needed. The flap should be thick enough to fill the defect and include the subdermal vascular plexus with at least a portion of the upper subcutaneous fat. In the absence of vital anatomic structures, the flap should become progressively thicker as it extends towards the base of the pedicle. This allows for larger caliber vessels to be recruited and may increase the likelihood of flap survival. If there is a question of sufficient blood supply, it may be appropriate to deepen the defect to accommodate a thicker flap with more robust perfusion.

In an advancement flap, the entire flap and surrounding skin should be undermined in all directions. This increases mobility, distributes tension more evenly, and, by spreading out the forces of contracture that will occur during wound healing, may limit the development of pincushioning.9 The exact undermining depth will vary with the location of the defect.10 In anatomic danger zones, such as over the zygoma and mandible and within the posterior triangle of the neck, the dissection must remain in the upper subcutaneous fat and above motor nerves, or permanent functional loss may result. Small defects on the forehead can be undermined in the subcutaneous fat above the frontalis fascia. However, large forehead defects are best dissected in the subgaleal plane. In hair-bearing locations such as the eyebrow, the undermining should be well into the subcutis and deep to the hair papillae. The nose should be undermined in the submuscular plane and the ears above the perichondrium. Once undermining has been performed, the flap is pulled gently into the defect to test its mobility. If this maneuver produces excessive tension, the most common cause is insufficient undermining. If tension remains despite wide undermining, the surgeon may consider lengthening the flap or converting it into a bilateral advancement flap to obtain additional tissue movement.11

By design, an advancement flap has skin edges of unequal lengths and closure of the primary defect almost always creates tissue redundancies along the outer edges of the surrounding skin. In most cases it is best to wait until the flap has been undermined and the primary defect closed before excising the standing cones, as tissue stretch and accommodation often leave them smaller than were expected preoperatively. Not infre-quently, the redundant tissue may be distributed by the “rule of halves” and will not require excision at all (Figure 4.3).12 If excision is necessary, one common method is to remove the standing cones as Burow’s triangles. These triangular cones can be excised at the base of the flap to create a flared or “hockey stick-shaped” suture line (Figure 4.1). Alternatively, in advancement flaps, they may be placed at any point along the skin edge (Figure 4.2). The traditional Burow’s triangle is oriented with its base placed along the wound edge and apex pointing away from the flap but may be inverted if a zigzag suture line is desired (Figure 4.5). This maneuver lengthens the overall suture line but may decrease the extent of contraction and in certain instances be more inconspicuous than a linear scar.13

FLAP MODIFICATIONS AND APPLICATIONS

H-plasty or Bilateral Advancement Flap

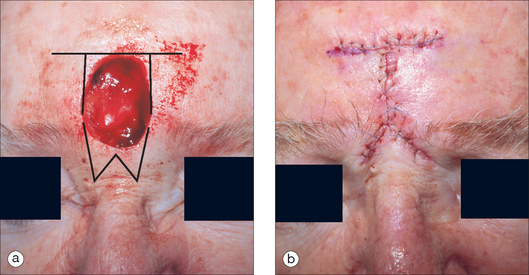

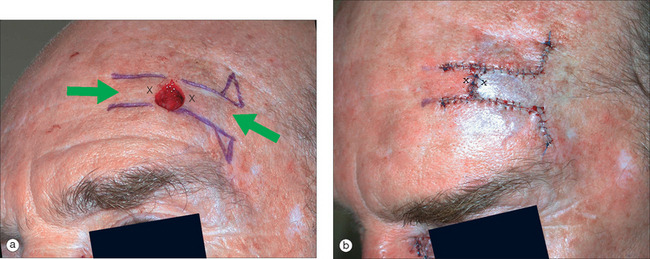

In the H-plasty or bilateral advancement or rectangular flap, parallel incisions are created on opposite sides of the defect. The two limbs of the flap are then advanced centrally to form an H-shaped suture line (Figure 4.6). This flap is most useful for locations with prominent horizontal lines such as the forehead, eyebrow, or glabella. The incision lines do not need to be exactly parallel and may be curved to conform to RSTLs. The advantage of an H-plasty is that each flap must advance only half as far as the single flap design. It is used in situations where a unilateral flap will not provide adequate tissue for tension-free wound closure.14 A significant drawback to the H-plasty is the multiple linear incisions required for its execution. Depending on the anatomic location, it may be prudent to incise and elevate one of the flaps on the least conspicuous side to see whether this achieves sufficient movement to close the defect. If there is excessive tension despite wide undermining, the second flap can be incised. However, keep in mind that both of the flaps do not need to be the same size. Once hemostasis has been achieved, the key suture is placed in the advancing edges of both flaps and closes the primary defect. Similar to the single advancement flap or U-plasty, tissue redundancies will occur along the edges of each flap that will need to be excised as Burow’s triangles or redistributed by the rule of halves.

Figure 4.6 (a) Similar defect as in Figure 4.1 but with less laxity, requiring a bilateral advancement flap or H-plasty to attain tension-free closure. (b) Immediate postoperative appearance with lateral standing cones excised as Burow’s triangles and medial standing cones redistributed by the rule of halves. Note that the actual flap length was shorter than the proposed incisions drawn preoperatively.

T-plasty

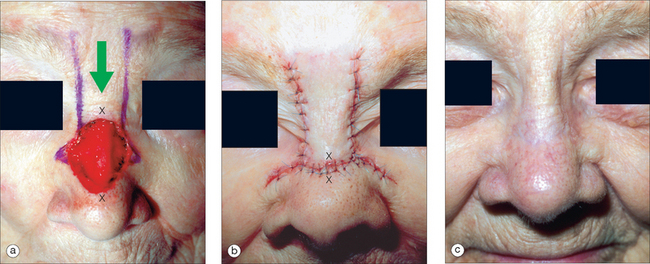

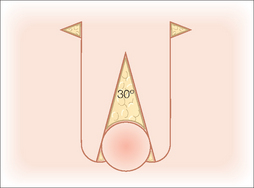

The T-plasty is a bilateral advancement flap that is also known as an A-to-T (when the defect is triangular), V-to-T (an inverted A-to-T), and O-to-T (when the defect is oval). The T-plasty is simple in its design, with the vertical height of the flap approximately twice the height of the defect and the base incisions extending one defect diameter in each direction (Figure 4.7).15 The incision lines do not need to be exactly linear and may be adjusted to conform to RSTLs (Figures 4.8, 4.9). If desired, an M-plasty can be placed in the apex of the triangle to decrease the vertical length of closure (Figure 4.10).16 Both flaps must be undermined widely to allow full mobility and tension-free closure.

Once hemostasis has been achieved, the key suture closes the primary defect and creates tissue redundancy along the base of the flap. These standing cones can be redistributed by the rule of halves, or excised. An alternative to the Burow’s triangle method is to excise the standing cones with curvilinear or crescentic incisions that redistribute the redundancy along the length of closure (Figure 4.11).17 This crescentic technique serves to lengthen the shorter advancing flap edge so that it more closely matches the length of the outer skin edge and thus mitigates the need for standing cone repair. It has the benefit of not creating additional incision lines and seems to be best suited when tissue is being moved over bony convexities. Because the vector of closure for the secondary defect changes with this maneuver and may become somewhat vertical, care must be taken not to elevate an adjacent free margin. This technique should not be used with an H- or U-plasty as the crescents would be excised from both edges of a flap that was relatively a narrow flap to begin, thereby possibly increasing the risk for ischemia. The key advantages of the T-plasty are that the T portion of the flap can be placed along anatomic boundaries, which hides a large portion of the scar within a cosmetic junction line, and its broad pedicles provide a reliable vascular supply.18

L-plasty

For defects with sufficient laxity, a unilateral T- or L-plasty may be performed. This single tangent flap takes advantage of tissue laxity that is displaced to one side of the defect. The vertical limb is designed similar to a T-plasty and the advancing limb should extend to the tissue reservoir along RSTLs. Tissue redundancy is either redistributed by the rule of halves (Figure 4.11) or lengthened with the crescentic technique (Figure 4.12 and 4.13). If excision of a Burow’s triangle is necessary, the suture line is no longer L-shaped and it is best referred to as a Burow’s triangle flap (see next section).

Burow’s Triangle Flap

In 1855, the German surgeon Karl August von Burow described a method for excision of the standing cones created by flap closure that bears his name, the Burow’s triangle. An advancement flap based on the excision of this redundant tissue is also named in his honor, the Burow’s triangle flap or Burow’s wedge flap. This flap moves in a single direction and is most effective for defects where tissue laxity is limited to one side of the defect. It is also useful for repair of defects in close proximity where advancement of the flap closes both defects with one movement.19

For a single defect, a linear incision is extended from the defect along a cosmetic junction or RSTL (Figure 4.14). This incision is usually two to three times as long as the width of the surgical defect but will vary with anatomic location and laxity. The incision may be extended to take advantage of a tissue reservoir or to allow better camouflage of the Burow’s triangle. For two defects in close proximity, the incision is placed along the bridge of tissue connecting them in such a way that the Burow’s triangles are displaced over both defects (Figure 4.15). This conserves tissue and closes both defects with one single motion.

Cheek advancement

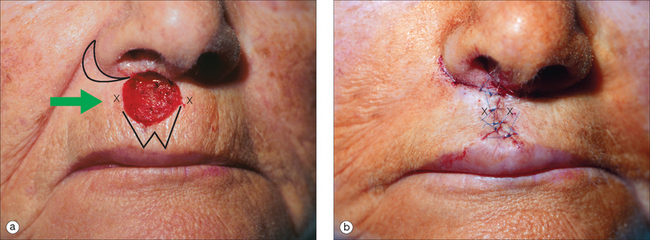

The cheek advancement flap is a widely based unilateral flap used to close medium- to large-sized defects of the medial cheek, nasofacial sulcus, and lateral nose. The primary movement is from lateral to medial. The inferior incision is frequently hidden within the melolabial fold or along RSTLs that run parallel to it. Depending on the location of the defect, the superior incision can be hidden along the nasofacial crease (Figure 4.16) or within the junction of the lower eyelid and cheek (Figure 4.17). One drawback to using an infraorbital incision is the potential for edema due to disruption of lymphatics, which usually lasts weeks to months and in some cases may be permanent.

In this flap, similar to other advancement flaps, the key suture closes the primary defect and creates standing cones that must be redistributed or excised. Suspension or tacking sutures that extend from the dermal portion of the flap to the periosteum of the underlying bone are used to decrease any downward pull on the eyelid or blunting of the nasofacial sulcus.20 Suspension sutures have the potential to impinge on blood flow and should be placed parallel to the blood vessels supplying the flap and not used if there is concern for ischemia. An alternative approach for reconstruction across a concavity is to advance the flap just up to the sulcus and suture it in place. The perpendicular surface is either allowed to heal by second intention (Figure 4.18) or repaired with a full-thickness skin graft harvested from a Burow’s triangle.

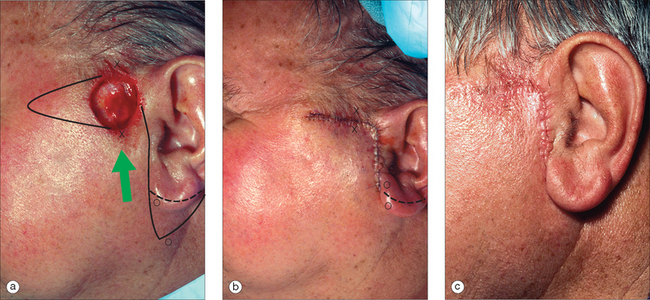

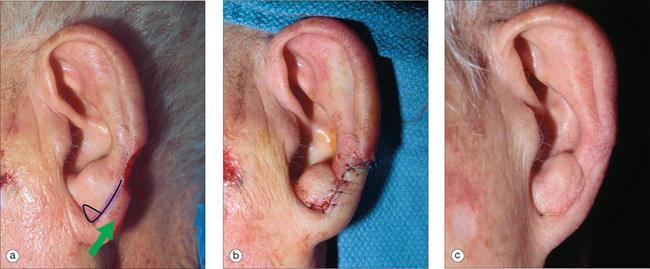

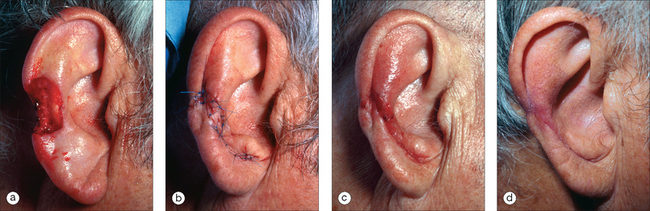

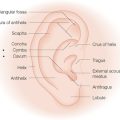

Helical rim advancement flap

The helical rim advancement flap can be an extremely useful method for repairing defects on the helix. As with other advancement flaps, sufficient tissue laxity must be present and the length-to-width ratio should not exceed 3 or 4:1. In the classic version, a full-thickness incision is placed through the cartilage and auricular skin and extended inferiorly from the defect along the scaphoid fossa to the lobule, which provides the tissue reservoir. For defects of the mid- to superior helix, this creates a long, narrow pedicle that is at risk for ischemia. In 1967 Antia and Buch described a modified chondrocutaneous advancement flap where the incision, instead of being through and through, is limited to the anterior auricular skin and cartilage.21 The postauricular skin is left intact and dissected above the perichondrium to the postauricular sulcus. This modification allows for the same mobility as the classical version but with a more reliable blood supply. In both flaps, after wide undermining is performed and hemostasis is achieved, the flap is advanced along the curvature of the helical rim to close the defect. If there is too much tension or the movement produces cupping of the ear, a Burow’s triangle can be placed in the lobule to lengthen the flap (Figure 4.19). Alternatively the rotational arc can be shortened by shaving the scaphal cartilage.22 For additional movement, a second flap can be incised superior to the helical crus, which is then detached and repositioned posteriorly toward the defect in a V-to-Y fashion. After the wound is closed, any redundant auricular skin can be excised as a Burow’s triangle. For defects extending to the anti-helix, the excised Burow’s triangle can be defatted and used as a full-thickness skin graft (Figure 4.20).

A significant disadvantage to both versions of the helical rim advancement flap is that they may cause ear asymmetry by shortening the overall height of the ear and/or by cupping.22 This is particularly true for large defects and if marked asymmetry is anticipated, another form of reconstruction should be considered. For unexpected asymmetry, the contralateral ear can be shortened with a wedge excision for a better match. A second concern is that any inversion of the suture line results in a highly visible notch along the curve of the helical rim (Figure 4.20). There are several methods for limiting this risk, which include careful wound edge eversion with vertical mattress sutures, modification of the flap tips with Z-plasties, and full-thickness interlocking step-cuts.23,24

Crescentic advancement flap

Webster’s perialar crescentic flap

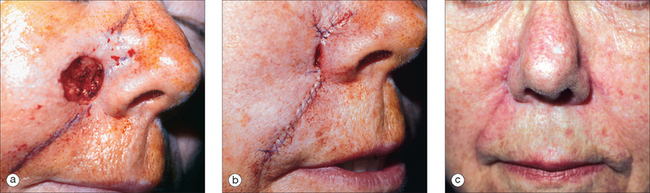

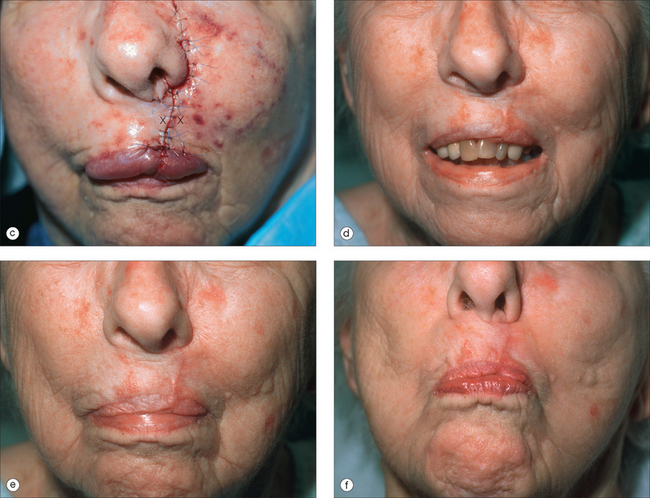

Webster published his experience with the crescentic perialar cheek advancement flap for upper lip repair in 1955.25 He described a method for lengthening the flap’s superior skin edge by excising a crescentic-shaped piece of tissue from the perialar cheek. This maneuver removes intervening redundant skin and facilitates the flap’s advancement into the upper lip defect (Figure 4.21). The superior standing cone is displaced laterally to the perialar sulcus instead of into the nostril. The inferior incision may be placed along the vermilion border but for smaller defects, an M-plasty may shorten the suture line sufficiently to maintain it within the cutaneous lip subunit (Figure 4.22).

Modifications of the crescentic advancement flap

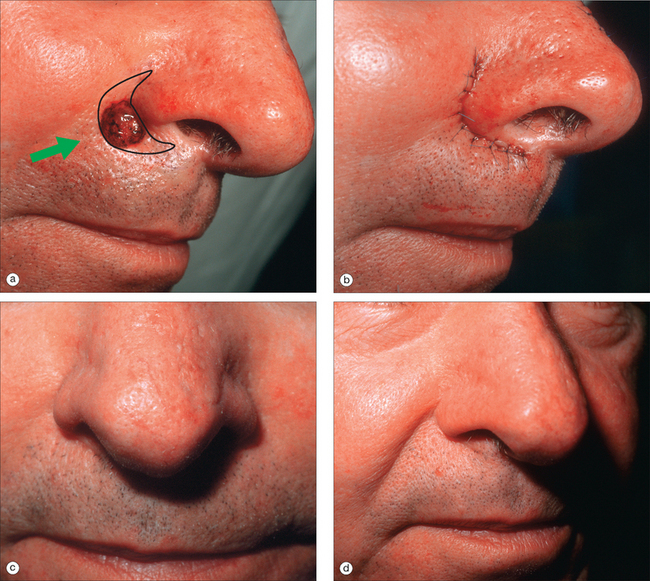

The perialar sulcus is an ideal location to hide an incision line and many variations from Webster’s classic design are possible. For example, defects up to a centimeter in diameter on the perialar lip and cheek can be advanced into the sulcus where the standing cones are excised as a continuation of the crescent and the suture line is hidden entirely within this natural curve (Figures 23, 24).

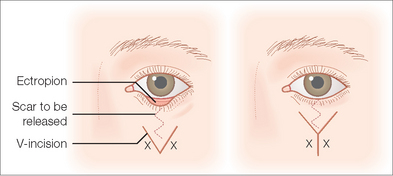

V to Y

The V–Y advancement flap is used to lengthen a structure or release a contracted scar. It is not to be confused with the island pedicle flap (discussed in Chapter 6). In the V–Y advancement flap, a V-shaped incision is placed in the contracted scar or structure to be lengthened. This releases the tethered skin and allows it to recoil to its natural position leaving a triangular defect (Figure 4.25). The edges of the defect are advanced toward each other, which pushes the flap forward and creates a Y-shaped suture line. The V–Y advancement flap is very useful for releasing burn scar contractures, distorted free margins (ectropion, eclabion), and lengthening the columella to enhance nasal tip protrusion.14

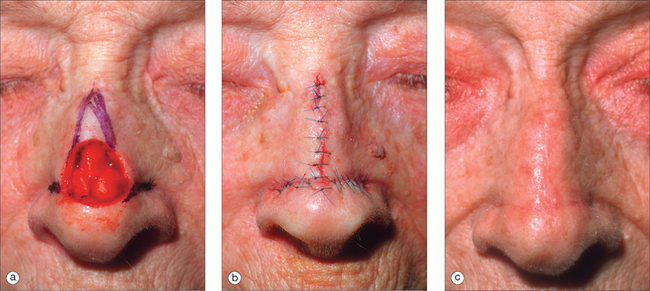

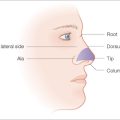

Rintala flap

In 1969, Rintala and Asko-Seljavaara reported their experience with a superiorly based rectangular advancement flap for closure of midline defects of the proximal to mid-nose (Figure 4.2).26 They suggested that the best locations for excision of Burow’s triangle are immediately above the eyebrows, at the corner of the eyes or proximal to the alar grooves. The flap length should be at least twice the vertical height of the defect and elevated above the periosteum in the submuscular plane. It must be dissected carefully from all adhesions, particularly those found in the canthal regions. The tension vectors created with this flap will elevate the nasal tip to some degree. If there is significant tip ptosis, this may be cosmetically pleasing. Conversely, if there is no ptosis, the upward nasal distortion may be unacceptable. There are no particular modifications from the standard advancement flap but when used in this area, it may be appropriately referred to as a Rintala flap.

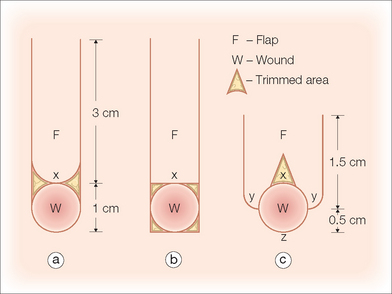

Peng flap

For repair of central nasal tip defects, Peng and colleagues suggested a “pinch” modification to the Rintala flap that shortens the vertical incision lines and widens the pedicle.27 The geometry of placing a Rintala flap into a circular defect necessitates that healthy tissue must be sacrificed, by either trimming the flap tips or squaring the defect. In the Peng modification, instead of vertical incisions, the flap limbs are extended laterally from the middle of the wound along the alar groove and then superiorly in a linear fashion along the nasofacial sulcus (Figure 4.26). The flap is advanced inferiorly and the tips are rotated medially to form a rounded and slightly convex tip. This maneuver shortens the overall flap length to 1.5 to 1.8 times the vertical height of the defect and does not effect flap survival. It does, however, elevate the ala slightly. Rowe and colleagues suggested starting the incision for the rotating arms of the flap as far distal as possible and not mid-defect as described by Peng et al (Figure 4.27).28 This modification decreases the amount of vertical advancement involved in the flap and increases the amount of rotation into the defect. This will serve to shorten the length of the lateral vertical incisions and help facilitate closure, given there is some laxity lateral to the defect. Careful attention must be paid to the position of the nasal ala during this closure. Any significant distortion may be cosmetically unacceptable.

DISADVANTAGES

No new substance is produced at the place itself but it is drawn from the neighbourhood; and when the change is small, this hardly robs any other part and may pass unnoticed; but when large, it cannot do so. … For instance, we should not attempt to make traction upon the lobules of the ears, the bridge of the nose, the margins of the nostrils or the corners of the lips.1

As noted by Celsus almost 2000 years ago, the two major drawbacks of an advancement flap are that in most circumstances it does not recruit tissue for closure and, unless diligently designed and executed, has a propensity to distort free margins. It is not the repair of choice for large defects without surrounding laxity or nearby tissue reservoirs. Another disadvantage is that most advancement flaps are designed with straight lines and thus, if not appropriately placed, may be highly visible.

1 Spencer WG. Celsus on medicine: Books VII–VIII volume VII. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994.

2 Larrabee WFJr. A finite element model of skin deformation. I. Biomechanics of skin and soft tissue: a review. Laryngoscope. 1986;96:399-405.

3 Dzubow LM. The dynamics of flap movement: effect of pivotal restraint on flap rotation and transposition. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1987;13:1348-1353.

4 Stell PM. Letter: Viability of skin flaps. Lancet. 1974;2:1385.

5 Larrabee WFJr., Holloway GAJr., Sutton D. Wound tension and blood flow in skin flaps. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1984;93:112-115.

6 Burget GC, Menick FJ. Aesthetic restoration of one-half of the upper lip. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;78:583-593.

7 Dzubow LM. Chemosurgical report: indications for a geometric approach to wound closure following Mohs surgery. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1987;13:480-486.

8 Brodland DG. Advancement flaps. In: Roenigk RK, Roenigk HK, editors. Roenigk & Roenigk’s dermatologic surgery: principles and practice. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1996:825-834.

9 Kaufman AJ, Kiene KL, Moy RL. Role of tissue undermining in the trapdoor effect of transposition flaps. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1993;19:128-132.

10 Boyer JD, Zitelli JA, Brodland DG. Undermining in cutaneous surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:75-78.

11 Larrabee WFJr., Sutton D. The biomechanics of advancement and rotation flaps. Laryngoscope. 1981;91:726-734.

12 Weisberg NK, Nehal KS, Zide BM. Dog-ears: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:363-370.

13 Suzuki S, Matsuda K, Nishimura Y. Proposal for a new comprehensive classification of V-Y plasty and its analogues: the pros and cons of inverted versus ordinary Burow’s triangle excision. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98:1016-1022.

14 Brown MD. Advancement flaps. In: Baker SR, Swanson NA, editors. Local flaps in facial reconstruction. St. Louis: Mosby; 1995:91-107.

15 Stevens CR, Tan L, Kassir R, Calhoun K. Biomechanics of A-to-T flap design. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:113-117.

16 Webster RC, Davidson TM, Smith RC, et al. M-plasty techniques. J Dermatol Surg. 1976;2:393-396.

17 Moody BR, Sengelmann RD. Standing cone avoidance via advancement flap modification. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:632-634. discussion 635.

18 Hirshowitz B, Mahler D. T-plasty technique for excisions in the face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1966;37:453-458.

19 Boggio P, Gattoni M, Zanetta R, Leigheb G. Burow’s triangle advancement flaps for excision of two closely approximated skin lesions. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:622-625.

20 Robinson JK. Placement of the tension-bearing suture in repairing the alar facial junction. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36:440-443.

21 Antia NH, Buch VI. Chondrocutaneous advancement flap for the marginal defect of the ear. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1967;39:472-477.

22 Calhoun KH, Slaughter D, Kassir R, Seikaly H, Hokanson JA. Biomechanics of the helical rim advancement flap. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;122:1119-1123.

23 Ramsey ML, Marks VJ, Klingensmith MR. The chondrocutaneous helical rim advancement flap of Antia and Buch. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21:970-974.

24 Butler CE. Reconstruction of marginal ear defects with modified chondrocutaneous helical rim advancement flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:2009-2013.

25 Webster JP. Crescentic peri-alar cheek excision for upper lip flap advancement with a short history of upper lip repair. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1955;16:434-464.

26 Rintala AE, Asko-Seljavaara S. Reconstruction of midline skin defects of the nose. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1969;3:105-108.

27 Peng VT, Sturm RL, Marsh TW. “Pinch modification” of the linear advancement flap. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1987;13:251-253.

28 Rowe D, Warshawski L, Carruthers A. The Peng flap: The flap of choice for the convex curve of the central nasal tip. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21:149-152.