Adrenals, urinary tract and testes

8.1

Adrenal calcification

1. Cystic disease – similar to that seen in the child. Blunt abdominal trauma is a much more common cause in adults. Bilateral in 15% of cases.

2. Carcinoma – irregular punctate calcifications seen in 30%. Average size of tumour is 14 cm and there is frequently displacement of the ipsilateral kidney.

3. Addison’s disease – now most commonly due to autoimmune disease or metastasis. Historically, when TB was a frequent cause, calcification was a common finding.

4. Ganglioneuroma – 40% occur over the age of 20 years. Slightly flocculent calcifications in a mass, which is usually asymptomatic. Large tumours may cause displacement of the adjacent kidney and/or ureter.

5. Inflammatory – primary tuberculosis and histoplasmosis.

6. Phaeochromocytoma – calcification is rare but when present is usually an ‘egg-shell’ pattern.

8.2

Incidental adrenal mass (unilateral)

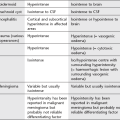

Functioning tumours

1. Conn’s adenoma – accounts for 70% of Conn’s syndrome. Usually small, 0.5–1.5 cm. Homogeneous, relatively low density due to build-up of cholesterol. 30% of Conn’s syndrome due to hyperplasia, which can occasionally be nodular and mimic an adenoma.

2. Phaeochromocytoma – usually large, > 5 cm, with marked contrast enhancement (beware hypertensive crisis with i.v. contrast medium). 10% malignant, 10% bilateral, 10% ectopic (of these 50% are located around the kidney, particularly the renal hilum. If CT does not detect, MIBG isotope scan may be helpful). 10% are multiple and usually part of MEN II syndrome, neurofibromatosis or von Hippel–Lindau.

3. Cushing’s adenoma – accounts for 10% of Cushing’s syndrome. Usually > 2 cm in diameter. 40% show slight reduction in density. 80% of Cushing’s syndrome due to excess ACTH from pituitary tumour or ectopic source (small cell carcinoma, pancreatic islet cell, carcinoid, medullary carcinoma of thyroid, thymoma) which causes adrenal hyperplasia not visible on CT scan. 10% of Cushing’s syndrome due to adrenal carcinoma. The possibilities for adrenal mass in Cushing’s syndrome are:

(a) Functioning adenoma/carcinoma.

(b) Coincidental non-functioning adenoma.

(c) Metastasis from small cell primary.

(d) Nodular hyperplasia, which occurs in 20% of Cushing’s syndrome due to pituitary adenoma.

4. Adrenal carcinoma – 50% present as functioning tumours (Cushing’s 35%, Cushing’s with virilization 20%, virilization 20%, feminization 5%).

Malignant tumours

1. Metastases – may be bilateral, usually > 2–3 cm, irregular outline with patchy contrast enhancement. Recent haemorrhage into a vascular metastasis (e.g. melanoma) can give a patchy high density on precontrast scan. In patients without a known extra-adrenal primary tumour the vast majority of adrenal masses are benign; even in the presence of a known primary malignant tumour many adrenal masses will still be benign (40% are metastases).

2. Carcinoma – typical features are:

3. Lymphoma – 25% also involve kidneys at autopsy. Lymphadenopathy will be seen elsewhere.

4. Neuroblastoma – > 5 cm. Calcification in 90%. Extends across midline. Nodes commonly surround and displace the aorta and inferior vena cava.

Benign

1. Non-functioning adenoma – occurs in 5% at autopsy. Usually relatively small (50% < 2 cm), homogeneous and well-defined.

2. Myelolipoma – 0.2% at autopsy. Rare benign tumour composed of adipose and haemopoietic tissue. 85% are found in the adrenal but extra-adrenal tumours (liver, retroperitoneum, pelvis) have been reported. Low attenuation on CT and may enhance. Mean diameter of 10 cm.

3. Angiomyolipoma – adrenal lesions are very rare in practice. Usually contain vascular tissue and fat density.

4. Cyst – well-defined, water density.

5. Post-traumatic haemorrhage – homogeneous, hyperdense. Occurs in 25% of severe trauma, 20% bilateral, 85% on right. Adrenal haemorrhage can also occur in vascular metastases, anticoagulant treatment and severe stress (e.g. surgery, sepsis, burns, hypotension).

6. Granulomatous disease (TB, histoplasmosis) – present as diffuse enlargement or as discrete mass. Can have a central cystic component, with/without calcification.

Boland, G. W., Blake, M. A., Hahn, P. F., Mayo-Smith, W. W. Incidental adrenal lesions: principles, techniques, and algorithms for imaging characterization. Radiology. 2008; 249(3):756–775.

Boland, G. W., Dwamena, B. A., Jagtiani Sangwaiya, M., et al. Characterization of adrenal masses by using FDG PET: a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test performance. Radiology. 2011; 259(1):117–126.

Low, G., Dhliwayo, H., Lomas, D. J. Adrenal neoplasms. Clin Radiol. 2012; 67:988–1000.

Park, B. K., Kim, C. K., Lee, J. H. Comparison of delayed enhanced CT and chemical shift MR for evaluating hyperattenuating incidental adrenal masses. Radiology. 2007; 243(3):760–765.

8.3

Bilateral adrenal masses

1. Metastases – bilateral in 15%. Common at autopsy. Most common primary sites are lung or breast; also melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, gastrointestinal tract, thyroid, contralateral adrenal gland. Usually does not affect adrenal function; may cause adrenal insufficiency if extensive (replacing > 80% of adrenal gland).

2. Phaeochromocytoma – bilateral in 10%.

3. Hyperplasia – adrenogenital syndromes result in symmetrically enlarged and thickened adrenal glands. Adrenocortical hyperplasia can cause bilateral adrenal enlargement but usually these are not visible on CT.

4. Spontaneous adrenal haemorrhage.

5. Lymphoma – primary adrenal lymphoma is rare. Usually presents with bilateral adrenal masses, often with adrenal hypofunction. Usually diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. Adrenal involvement occurs at autopsy in up to 25% with disseminated lymphoma, usually with no associated adrenal insufficiency.

6. Granulomatous disease – histoplasmosis/TB. Can be acute or chronic. Patients with adrenal masses and adrenal failure caused by chronic disseminated histoplasmosis may have symptoms and CT findings that are indistinguishable from those of malignancy.

8.4

Adrenal pseudotumours

Imaging structures mimicking adrenal mass

1. Exophytic upper pole renal mass – requires sagittal or coronal reconstructions and thin-section CT.

2. Gastric diverticulum – give oral contrast.

3. Splenic lobation/accessory spleen – give intravenous contrast, should enhance to the same level as the body of the spleen.

4. Prominent lobation of the hepatic lobe, or hepatic tumour.

5. Varices – give intravenous contrast.

6. Large mass in tail of pancreas – give intravenous contrast, pancreatic mass usually displaces splenic vein posteriorly, whereas adrenal mass displaces it anteriorly.

7. Fluid-filled colon – give intraluminal contrast and thin-section CT. Intraluminal gas is diagnostic.

8.5

Mibg imaging

The scintigraphic distribution of 131I MIBG occurs in organs with adrenergic innervation or those that process catecholamines for excretion.

8.6

Congenital renal anomalies

These may be anomalies of position, of form or of number.

Anomalies of position

1. Pelvic kidney – ectopic kidney due to failure of renal ascent. There is non-rotation with anteriorly positioned renal pelvis in most cases. Blood supply is from the iliac artery or the aorta. Most ectopic kidneys are asymptomatic, notwithstanding the fact that pelvic kidneys are more susceptible to trauma and infection and may complicate natural childbirth later in life.

2. Ectopic kidney – in the case of intrathoracic kidney, usually an acquired duplication through the foramen of Bochdalek. Can also be presacral or at the lower lumbar level.

Anomalies of form

1. Horseshoe kidney – two kidneys joined by parenchymal/fibrous isthmus. Most common fusion anomaly with incidence of 1 in 400 births. Fusion of right and left kidneys at lower pole in 90%. Abnormal axis of each kidney (bilateral malrotation). Renal pelves and ureters situated anteriorly and renal long axis medially oriented. Associated with other anomalies in 50% (e.g. vesicoureteral reflux, ureteral duplication, genital anomalies, Turner’s syndrome).

2. Pancake/discoid kidney – bilateral fused pelvic kidneys, usually near the aortic bifurcation.

3. Crossed renal ectopia – kidney is located on opposite side of midline from its ureteral orifice. Usually L > R. The lower kidney is usually ectopic. In 90% there is fusion of both kidneys (= crossed fused ectopia). May be associated with anorectal anomalies and renal dysplasia. Slightly increased incidence of calculi.

4. Renal hypoplasia – incomplete development results in a smaller (< 50% of normal size) kidney with fewer calyces and papillae. Normal function.

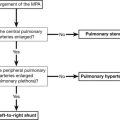

Anomalies of number

1. Unilateral renal agenesis – 1 : 1000 live births. Increased incidence of extrarenal abnormalities (meningomyelocoele, ventricular septal defect, intestinal tract strictures, imperforate anus, unicornuate uterus skeletal abnormalities). Hyperplastic normal solitary kidney – up to twice normal size.

2. Bilateral renal agenesis – Potter syndrome. 1 : 10,000 live births. Invariably fatal in first few days of life due to pulmonary hypoplasia secondary to the associated oligohydramnios.

3. Supernumerary kidney – very rare. Most commonly on left side caudal to normal kidney.

Cohen, H. L., Kravets, F., Zucconi, W., et al. Congenital abnormalities of the genitourinary system. Semin Roentgenol. 2004; 39(2):282–303.

Philip, J., Kenney, P. J., Spirt, B. A., et al. Genitourinary anomalies: radiologic–anatomic correlations. Radiographics. 1984; 4:233–260.

Servaes, S., Epelman, M. The current current state of imaging pediatric genitourinary anomalies and abnormalities. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2013; 42(1):1–12.

8.7

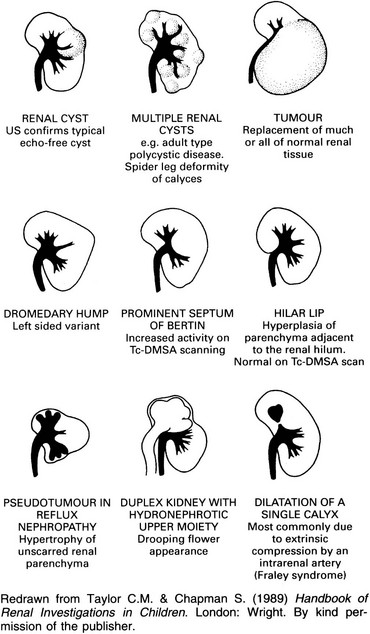

Localized bulge of the renal outline

1. Cyst – well-defined nephrographic defect with a thin wall on the outer margin. Beak sign. Displacement and distortion of smooth-walled calyces without obliteration.

2. Tumour – mostly renal cell carcinoma in adults and Wilms’ tumour in children. See 8.21.

3. Fetal lobation – the lobule directly overlies a normal calyx. Normal interpapillary line. See 8.8.

4. Dromedary hump – on the midportion of the lateral border of the left kidney. Occurs secondary to prolonged pressure by spleen during fetal development. The arc of the interpapillary line parallels the renal contour.

5. Splenic impression – on the left side only. This produces an apparent bulge inferiorly.

6. Enlarged septum of Bertin – overgrowth of renal cortex from two adjacent renal lobules. Usually between upper and interpolar portion. Excretory urography shows a pseudomass with calyceal splaying and associated short calyx ± attempted duplication. Tc-DMSA accumulates normally or in excess. On US echogenicity is usually similar to normal renal cortex but may be of increased echogenicity. CT – enhances similar to cortex.

7. Localized compensatory hypertrophy – e.g. adjacent to an area of pyelonephritic scarring.

8. Acute focal nephritis (lobar nephronia) – usually an ill-defined hypoechoic mass on US, but may be hyperechoic. CT shows an ill-defined, low-attenuation, wedge-shaped mass with reduced contrast enhancement.

9. Abscess – loss of renal outline and psoas margin on the control film. Scoliosis concave to the involved side. Initially there is no nephrographic defect, but following central necrosis there will be a central defect surrounded by a thick irregular wall. Adjacent calyces are displaced or effaced.

10. Non-functioning moiety of a duplex – usually a hydronephrotic upper moiety. Delayed films may show contrast medium in the upper moiety calyces. Lower moiety calyces display the ‘drooping lily’ appearance.

Bhatt, S., MacLennan, G., Dogra, V. Renal pseudotumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007; 188(5):1380–1387.

O’Connor, S. D., Pickhardt, P. J., Kim, D. H., et al. Incidental finding of renal masses at unenhanced CT: prevalence and analysis of features for guiding management. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011; 197(1):139–145.

Silverman, S. G., Israel, G. M., Herts, B. R., Richie, J. P. Management of the incidental renal mass. Radiology. 2008; 249(1):16–31.

8.8

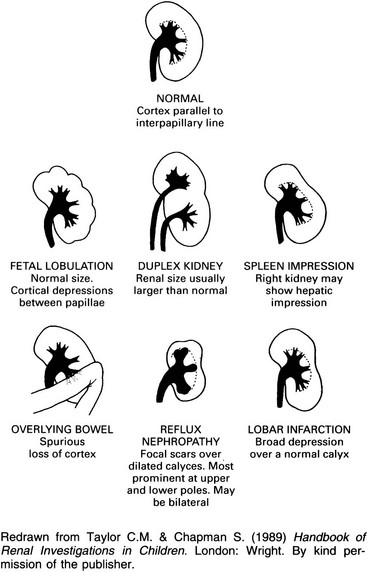

Unilateral scarred kidney

1. Reflux nephropathy – a focal scar over a dilated calyx. Usually multifocal and may be bilateral. Scarring is most prominent in the upper and lower poles. Minimal scarring, especially at a pole, may produce decreased cortical thickness with a normal papilla and is then indistinguishable from lobar infarction.

2. Tuberculosis – calcification differentiates it from the other members of this section.

3. Lobar infarction – a broad contour depression over a normal calyx. Normal interpapillary line.

4. Renal dysplasia – a forme fruste multicystic kidney. Dilated calyces. Indistinguishable from chronic pyelonephritis. Arteriography outlines a small threadlike renal artery.

8.9

Unilateral small smooth kidney

Prerenal = vascular

1. Ischaemia due to renal artery stenosis – ureteric notching is due to enlarged collateral vessels and differentiates this from the other causes in this group. See 8.28.

2. Radiation nephritis – at least 23 Gy over 5 weeks. The collecting system may be normal or small. Depending on the size of the radiation field, both, one or just part of one kidney may be affected. There may be other sequelae of radiotherapy, e.g. scoliosis following radiotherapy in childhood.

3. End result of renal infarction – due to previous severe trauma involving the renal artery or renal vein thrombosis. The collecting system does not usually opacify during excretion urography.

8.10

Bilateral small smooth kidneys

8.11

Unilateral large smooth kidney

Renal = parenchymal

1. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease* – asymmetrical bilateral enlargement, but 8% of cases are unilateral. Lobulated rather than completely smooth.

2. Duplex kidney – F : M = 2 : 1. Equal incidence on both sides and 20% are bilateral. Incomplete more common than complete. Only 50% are bigger than the contralateral kidney; 40% are the same size; 10% are smaller.

3. Crossed fused ectopia – see 8.6.

5. Acute pyelonephritis – impaired excretion of contrast medium ± dense nephrogram. Attenuated calyces but may have non-obstructive pelvicalyceal or ureteric dilatation. Completely reversible within a few weeks of clinical recovery.

Davidson, A. J. Renal parenchymal disease. In: Davidson A. J., Hartman D. S., Choyke P. L., Wagner B. J., eds. Radiology of the kidney and genitourinary tract. third ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1999:73–358.

Pickhardt, P. J., Lonergan, G. J., Davis, C. J., Jr., et al. Infiltrative renal lesions: radiologic–pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2000; 20:215–243.

8.12

Bilateral large smooth kidneys

It is often difficult to distinguish, radiologically, the members of this group from one another. The appearance of the nephrogram may be helpful – see 8.25. Associated clinical and radiological abnormalities elsewhere are often more useful, e.g. in sickle-cell anaemia, Goodpasture’s disease and acromegaly.

8.13

Renal calcification

Dystrophic calcification due to localized disease

Usually one kidney or part of one kidney.

(a) Tuberculosis – variable appearance of nodular, curvilinear or amorphous calcification. Typically multifocal with calcification elsewhere in the urinary tract.

(b) Hydatid – the cyst is usually polar and calcification is curvilinear or heterogeneous. 50% of echinococcal cysts calcify.

(c) Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis – large obstructive calculus in 80% of cases.

(d) Abscess – tuberculous abscess frequently calcifies. Pyogenic abscesses rarely calcify.

(a) Carcinoma – in 6% of carcinomas. Usually amorphous or irregular, but occasionally curvilinear.

3. Cysts – usually related to previous infection or haemorrhage.

8.14

Renal calculi

Non-opaque

Uric acid, xanthine, matrix (mucoprotein) and stones related to treatment with indinavir.

Calcium-containing

1. With normocalcaemia – obstruction, urinary tract infection, prolonged bed rest, ‘horseshoe’ kidney, vesical diverticulum, renal tubular acidosis, medullary sponge kidney and idiopathic hypercalciuria.

2. With hypercalcaemia – hyperparathyroidism, milk-alkali syndrome, excess vitamin D, idiopathic hypercalcaemia of infancy and sarcoidosis.

Pure calcium oxalate due to hyperoxaluria

1. Primary hyperoxaluria – rare. AR. 65% present below 5 years of age. Radiologically – nephrocalcinosis (generally diffuse and homogeneous but may be patchy), recurrent nephrolithiasis, dense vascular calcification, osteopenia or renal osteodystrophy and abnormal metaphyses (dense and/or lucent bands).

2. Enteric hyperoxaluria – due to a disturbance of bile acid metabolism. Mainly in patients with small bowel disease, either Crohn’s disease or surgical resection.

Blake, S. P., McNicholas, M. M., Raptopoulos, V. Nonopaque crystal deposition causing ureteric obstruction in patients with HIV undergoing indinavir therapy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999; 171(3):717–720.

Dyer, R. B., Chen, M. Y., Zagoria, R. J. Abnormal calcifications in the urinary tract. Radiographics. 1998; 18(6):1405–1424.

Sandhu, C., Anson, K. M., Patel, U. Urinary tract stones – Part I: role of radiological imaging in diagnosis and treatment planning. Clin Radiol. 2003; 58(6):415–421.

Sandhu, C., Anson, K. M., Patel, U. Urinary tract stones – Part II: current state of treatment. Clin Radiol. 2003; 58(6):422–423.

8.15

Signs of urinary tract stone disease on CT

1. Calcification within the renal collecting system or ureteric lumen.

3. Asymmetric inflammatory change of the perinephric fat.

6. Soft tissue rim sign – refers to a soft tissue ring surrounding the calcification, representing the oedematous wall of the surrounding ureter, and may be helpful in differentiating a phlebolith from a ureteric stone.

8.16

Mimics of renal colic on unenhanced CT urography

Non-stone genitourinary

1. Pyelonephritis – asymmetric perinephric stranding or mild renal enlargement. Mild disease may have no signs on unenhanced CT. Following intravenous contrast administration, pyelonephritis may be seen as a focal wedge-shaped region of low attenuation or a more widespread striated enhancement of the kidney. Renal or perinephric abscesses are rare sequelae.

2. Congenital pelviureteric obstruction.

3. Ureteric obstruction secondary to abdominal and pelvic lymphadenopathy.

Gastrointestinal

1. Appendicitis – the normal appendix is usually less than 6 mm wide, thin walled, and may contain an appendicolith. Gas in the lumen may be both a normal and abnormal finding. Look for dilatation of the appendix to more than 6 mm, inflammatory stranding of the periappendiceal or pericaecal fat, and surrounding phlegmon or abscess. A faecalith within a fluid collection in the right lower quadrant is very helpful for making the diagnosis of a perforated appendicitis.

2. Diverticulitis – characteristic findings include inflammation of pericolic fat related to diverticula, focal colonic wall thickening, thickening of adjacent fascia, thickening of the root of the mesentery and intra-abdominal abscess. Most inflamed diverticula are usually within the sigmoid or descending colon.

3. Small bowel diverticulitis and Meckel diverticulitis may mimic renal colic.

Vascular

1. Renal infarction – unilateral perinephric stranding is suggestive of a dissection flap into the renal artery.

4. Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm – crescent-shaped area of high attenuation, higher than intraluminal blood, in the wall of an abdominal aortic aneurysm. Periaortic stranding or haemorrhage, > 60 HU is indicative of active bleeding.

5. Aortic dissection – high attenuation on unenhanced CT in the wall of the aorta indicates intraluminal haematoma, displacement of intimal calcification into the aortic lumen; renal infarction.

6. Isolated SMA dissection – rare; signs include perivascular fat stranding, vessel enlargement, irregular contour and displacement of intimal calcification. Secondary signs of bowel compromise are bowel wall thickening, pneumatosis and bowel distension.

7. SMA thrombosis or embolism – may present with pain radiating to one side; the signs are an enlarged vessel, perivascular stranding and high-attenuation material within the vessel caused by clotted blood.

8. Intraperitoneal and retroperitoneal haemorrhage – trauma-related, spontaneous haemorrhage is usually related to use of anticoagulants, also in bleeding diatheses, vasculitis (polyarteritis nodosa), splenic rupture and certain neoplasms.

Miscellaneous conditions

Focal fatty intraperitoneal infarctions – e.g. epiploic appendagitis and focal omental infarction. Signs of fat surrounding the colon include fat stranding without bowel wall thickening and a well-circumscribed fatty mass with a centre of high attenuation. These two conditions may be indistinguishable, are treated conservatively and are usually self-limiting.

8.17

Nephrocalcinosis

Medullary (pyramidal)

The first three causes account for 70% of cases.

1. Medullary sponge kidney – a variable portion of one or both kidneys contains numerous small medullary cysts which communicate with tubules and therefore opacify during excretion urography. The cysts contain small calculi, giving a ‘bunch of grapes’ appearance. Big kidneys. ± Multiple cysts or large medullary cystic cavities which may be > 2 cm in diameter. (Although not strictly a cause of nephrocalcinosis, because it comprises calculi in ectatic ducts, it is included here because of the plain film findings which simulate nephrocalcinosis.)

3. Renal tubular acidosis – may be associated with osteomalacia or rickets. Calcification tends to be more severe than that due to other causes. It is the commonest cause in children. Almost always a distal tubular defect.

4. Renal papillary necrosis – calcification of necrotic papillae. See 8.26.

5. Causes of hypercalcaemia or hypercalciuria

6. Preterm infants – in up to two-thirds. Risk factors include extreme prematurity, severe respiratory disease, gentamicin use, and high urinary oxalate and urate excretion. 50% resolve spontaneously.

7. Primary hyperoxaluria – rare. AR. 65% present below 5 years of age (younger than the other causes). Radiologically – nephrocalcinosis (generally diffuse and homogeneous but may be patchy), recurrent nephrolithiasis, dense vascular calcification, osteopenia or renal osteodystrophy and abnormal metaphyses (dense and/or lucent bands).

Habbig, S., Beck, B. B., Hoppe, B. Nephrocalcinosis and urolithiasis in children. Kidney Int. 2011; 80(12):1278–1291.

Hoppe, B., Kemper, M. J. Diagnostic examination of the child with urolithiasis or nephrocalcinosis. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010; 25(3):403–413.

Narendra, A., White, M. P., Rolton, H. A., et al. Nephrocalcinosis in preterm babies. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2001; 85:F207–213.

8.18

Cortical defects in radionuclide renal images

8.19

Renal cystic disease

Polycystic disease*

1. Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease.

2. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease.

Polycystic renal disease is associated with hepatic cysts in approximately 60% of cases.

Haemorrhage into cysts relatively common, so may be of varying density. Associated with increased incidence of renal cell carcinoma.

Cortical cysts

1. Simple cyst – unilocular. Increase in size and number with age. Thin-walled, no enhancement. Occasionally haemorrhage can occur within one, producing a round hyperdense lesion.

2. Multilocular cystic nephroma.

3. Syndromes associated with cysts – Zellweger’s syndrome, tuberous sclerosis, Turner’s syndrome, von Hippel–Lindau disease, trisomy 13 and 18.

4. End-stage renal disease and haemodialysis – in 8–13% of patients in renal failure not on dialysis; 10–20% of patients after 1–3 years of dialysis; > 90% of patients after 5–10 years of dialysis but can involute after a successful renal transplant. Diagnosis based on finding at least 3–5 cysts in each kidney. Cysts are of variable size and occur in cortex and medulla. Increased incidence of renal cell carcinoma (7%), particularly when on dialysis.

Medullary cysts

1. Calyceal cysts (diverticulum) – small, usually solitary cyst communicating via an isthmus with the fornix of a calyx.

2. Medullary sponge kidney – bilateral in 60–80%. Multiple, small, mainly pyramidal cysts which opacify during excretion urography and contain calculi.

3. Papillary necrosis – see 8.26.

4. Juvenile nephronophthisis (medullary cystic disease) – usually presents with polyuria and progressive renal failure. Positive family history. Normal or small kidneys. US shows a few medullary or corticomedullary cysts, loss of corticomedullary differentiation and increased parenchymal echogenicity.

Miscellaneous intrarenal cysts

2. Neoplastic – cystic degeneration of a carcinoma. 5% of renal cell carcinomas are cystic. Suspect if thick walls or separations but this may just indicate previous infection/haemorrhage in cyst.

3. Traumatic – intrarenal haematoma.

4. Cystic hamartoma – usually large with thick capsule and septations.

Extraparenchymal renal cysts

1. Parapelvic cyst – located in or near the hilum, but does not communicate with the renal pelvis and therefore does not opacify during urography. Simple or multilocular; single or multiple, unilateral or bilateral. It compresses the renal pelvis and may cause hydronephrosis.

2. Perinephric cyst – beneath the capsule or between the capsule and perinephric fat. Secondary to trauma, obstruction or replacement of haematoma. It may compress the kidney, pelvis or ureter, leading to hydronephrosis or causing displacement of the kidney.

Bae, K. T., Grantham, J. J. Imaging for the prognosis of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2010; 6(2):96–106.

Choyke, P. L. Acquired cystic kidney disease. Eur Radiol. 2000; 10:1716–1721.

Katabathina, V. S., Kota, G., Dasyam, A. K., et al. Adult renal cystic disease: a genetic, biological, and developmental primer. Radiographics. 2010; 30(6):1509–1523.

Meister, M., Choyke, P., Anderson, C., Patel, U. Radiological evaluation, management, and surveillance of renal masses in Von Hippel–Lindau disease. Clin Radiol. 2009; 64(6):589–600.

Pedrosa, I., Saiz, A., Arrazola, L., et al. Hydatid disease: radiologic and pathologic features and complications. Radiographics. 2000; 20:795–817.

Saunders, A. J., Denton, E., Stephens, S., et al. Cystic kidney disease presenting in infancy. Clin Radiol. 1999; 54:370–376.

8.20

CT findings in renal cystic disease

Hindman, N. M., Bosniak, M. A., Rosenkrantz, A. B., et al. Multilocular cystic renal cell carcinoma: comparison of imaging and pathologic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012; 198(1):W20–26.

Israel, G. M., Bosniak, M. A. How I do it: evaluating renal masses. Radiology. 2005; 236:441–450.

Israel, G. M., Hindman, N., Bosniak, M. A. Evaluation of cystic renal masses: comparison of CT and MR imaging by using the Bosniak classification system. Radiology. 2004; 231(2):365–371.

Katabathina, V. S., Kota, G., Dasyam, A. K., et al. Adult renal cystic disease: a genetic, biological, and developmental primer. Radiographics. 2010; 30(6):1509–1523.

Smith, A. D., Remer, E. M., Cox, K. L., et al. Bosniak category IIF and III cystic renal lesions: outcomes and associations. Radiology. 2012; 262(1):152–160.

8.21

Fat-containing renal mass

1. Angiomyolipoma – 80% of cases are sporadic and 20% are associated with tuberous sclerosis. 80% of sporadic cases are on the right side. Angiomyolipomas are seen in up to 80% of patients with tuberous sclerosis where they are commonly large, bilateral and multifocal. May be the only evidence of tuberous sclerosis. Also seen in neurofibromatosis and von Hippel–Lindau.

Ultrasound, CT and MRI: fat densities within the tumours.

NB. Fat may occasionally be identified within Wilms’ tumour.

2. Renal cell carcinoma – invasion of perirenal fat or intratumoral metaplasia into fatty marrow (in one-third of renal cell carcinomas if < 3 cm).

3. Lipoma – no different on CT to angiomyolipoma. Diagnosis only confirmed at pathological inspection.

4. Liposarcoma – large, bulky and peripheral. Usually capsular, extends into perirenal space and hypovascular at angiography.

6. Oncocytoma – entrapment of perirenal or sinus fat or production of fatty marrow in association with osseous metaplasia.

7. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis.

8. Teratoma – very rare. Contains varying amounts of fat and calcification.

8.22

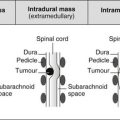

Renal neoplasms in an adult

Malignant

1. Renal cell carcinoma – 90% of adult malignant tumours. Bilateral in 10% and an increased incidence of bilaterality in polycystic kidneys and von Hippel–Lindau disease. A mass lesion (showing irregular or amorphous calcification in 10% of cases). Calyces are obliterated, distorted and/or displaced. Half-shadow filling defect in a calyx or pelvis. Arteriography shows a typical pathological circulation in the majority.

2. Urothelial carcinoma – usually papilliferous. May obstruct or obliterate a calyx or obstruct a whole kidney. Seeding may produce a second lesion further down the urinary tract. Bilateral tumours are rare. Calcification in 2%.

3. Squamous cell carcinoma – ulcerated plaque or stricture. 50% are associated with calculi. There is usually a large parenchymal mass before there is any sizeable intrapelvic mass. No calcification. Avascular at arteriography.

4. Leukaemia/lymphoma – bilateral large smooth kidneys. Thickened parenchyma with compression of the pelvicalyceal systems.

5. Metastases – not uncommon. Usually multiple. Bronchus, breast and stomach.

Benign

1. Hamartoma – usually solitary but often multiple and bilateral in tuberous sclerosis. Diagnostic appearance on the plain film of radiolucent fat (but only observed in 9%). Other signs are of any mass lesion, and angiography does not differentiate from renal cell carcinoma.

2. Adenoma – usually small and frequently multiple. Majority are found at autopsy. Hypovascular at arteriography.

3. Others – myoma, lipoma, haemangioma and fibroma are all rare.

Browne, R. F., Meehan, C. P., Colville, J., et al. Transitional cell carcinoma of the upper urinary tract: spectrum of imaging findings. Radiographics. 2005; 25(6):1609–1627.

Helenon, O., Correas, J. M., Balleyguier, C., et al. Ultrasound of renal tumours. Eur Radiol. 2001; 11:1890–1901.

Israel, G. M., Bosniak, M. A. Pitfalls in renal mass evaluation and how to avoid them. Radiographics. 2008; 28(5):1325–1338.

Prasad, S. R., Humphrey, P. A., Catena, J. R., et al. Common and uncommon histologic subtypes of renal cell carcinoma: imaging spectrum with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2006; 26(6):1795–1806.

Wagner, B. J., Wong-You-Cheong, J. J., Davis, C. J., Jr. Adult renal hamartomas. Radiographics. 1997; 17(1):155–169.

8.23

CT of focal hypodense renal lesions

Tumours

(a) Renal cell carcinoma – usually inhomogeneous and irregular if large.

(c) Lymphoma – usually late-stage non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma; only 5% at initial staging. 70% multiple and bilateral. Usually rounded in appearance.

(d) Urothelial carcinoma – can infiltrate and mimic renal cell carcinoma.

(a) Oncocytoma – adenoma arising from proximal tubular cells. Round, well-defined, homogeneous (usually high-density precontrast, low-density postcontrast), ± central stellate low-density scar if tumour bigger than 3 cm.

(b) Angiomyolipoma – well-defined containing fat densities. Association with tuberous sclerosis.

Infection

1. Abscess – thick irregular walls ± perirenal fascial thickening, but this can occur in malignancy.

2. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis – obstructing calculus seen in 80% cases leading to chronic sepsis, perinephric fluid collections and fistula formation.

3. Acute focal bacterial nephritis – wedge-shaped low density ± radiating striations after intravenous contrast.

Craig, W. D., Wagner, B. J., Travis, M. D. Pyelonephritis: radiologic–pathologic review. Radiographics. 2008; 28(1):255–277.

Pallwein-Prettner, L., Flöry, D., Rotter, C. R., et al. Assessment and characterisation of common renal masses with CT and MRI. Insights Imaging. 2011; 2(5):543–556.

Urban, B. A., Fishman, E. K. Renal lymphoma: CT patterns with emphasis on helical CT. Radiographics. 2000; 20:197–212.

8.24

Renal sinus mass

Neoplastic

1. Urothelial carcinoma – intraluminal filling defect on excretory urography, centred in the renal pelvis which secondarily invades the renal sinus and the renal parenchyma.

2. Squamous cell carcinoma – strongly associated with renal calculi.

3. Metastasis to sinus lymph nodes.

4. Mesenchymal tumour – e.g. lipoma, fibroma, haemangioma.

5. Retroperitoneal tumours that extend into the renal sinus – any retroperitoneal tumour but lymphoma most commonly.

6. Renal parenchymal tumours that project into the renal sinus – renal cell carcinoma, multilocular cystic nephroma.

Non-neoplastic lesions

1. Sinus lipomatosis – echogenic central sinus complex on ultrasound. CT and MRI directly reveal fatty nature.

2. Peripelvic cyst – multiple, small, benign, extraparenchymal cysts, probably lymphatic in origin, which appear to arise in the sinus itself. Distinguished from hydronephrosis by contrast-enhanced CT.

3. Parapelvic cyst – single, larger cyst protruding into the sinus, most likely originating from the adjacent parenchyma. Large cysts may cause haematuria, hypertension or hydronephrosis by local compression.

4. Vascular – renal artery aneurysm, arteriovenous communication or renal vein varix can manifest as parapelvic masses or peripelvic lesions. Colour Doppler or contrast-enhanced CT used for diagnosis.

5. Inflammatory – usually extension into the sinus from chronic or severe pyelonephritis.

6. Haematoma – as a complication of anticoagulant therapy or less commonly secondary to trauma.

7. Urinoma – usually associated with ureteral obstruction secondary to stone disease or trauma.

8.25

Neoplastic and proliferative disorders of the perinephric space

Soft tissue rind

(a) Persistence of multiple macroscopic or diffuse nephrogenic rests.

(b) Distribution classified as intralobar or perilobar.

(c) Perilobar is more common and is associated with Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome, sporadic aniridia and WAGR syndrome (Wilms’ tumour, aniridia, genitourinary anomalies and mental retardation).

(d) Perinephric nephroblastomatosis – appears as a homogeneous, low-attenuation rind of subcapsular soft tissue with minimal enhancement.

(e) Malignant transformation to Wilms’ tumour occurs in 35% of patients.

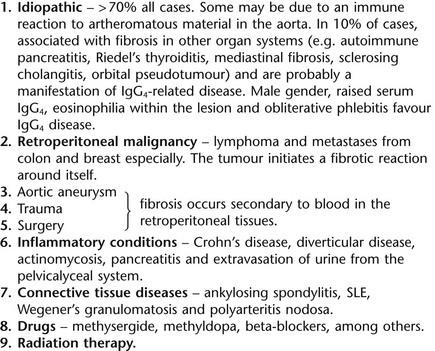

2. Retroperitoneal fibrosis (RPF)

(a) Fibrotic reaction resulting in encasement of the abdominal aorta, IVC and ureters, and may extend into the perinephric space.

(b) Two to three times more common in men, presenting usually between 40 and 60 years of age.

(c) Idiopathic in 70%, or secondary to inflammatory disorders, malignancy or medications.

(d) May be isolated or occur as part of multifocal fibrosclerosis (e.g. IgG4 disease) together with autoimmune pancreatitis, sclerosing cholangitis, Riedel’s thyroiditis and scleroderma.

(e) Male gender, raised serum IgG4, eosinophilia within the lesion and obliterative phlebitis favour IgG4 disease.

(f) Differentiation of benign disease from malignant disease is difficult.

3. Erdheim–Chester disease (ECD)

(a) Rare, non-Langerhans’, histiocytic disorder.

(b) Affects middle-aged adults, mean age 53 years.

(c) May involve long bones, lungs, skin, pituitary gland, kidneys, adrenal gland and heart.

(d) Lower extremity bone pain is the most common symptom.

(e) Renal involvement in 29% and progressive fibrous perinephritis can lead to renal failure.

(f) Homogeneous soft tissue in the perinephric space, giving a hairy kidney appearance.

4. Extramedullary haemopoiesis

(a) A physiological compensatory mechanism for failure of erythropoiesis.

(b) Typically hypodense on CT and hypointense on T1W and mildly hyperintense on T2W imaging.

(c) Commonly occurs in the liver or spleen but may also be found in the kidneys, breast, skin and adrenal glands.

(e) May present with abdominal pain or renal failure due to parenchymal involvement or ureteric compression.

(f) Hepatosplenomegaly and paraspinal soft tissue can help in the diagnosis.

(a) Perinephric lymphoma commonly due to extension of retroperitoneal or renal lymphoma.

(b) Most often associated with an intermediate- to high-grade non-Hodgkin’s B-cell type.

(c) Less than 10% of cases of perinephric lymphoma are isolated to the perinephric space.

(d) Usually clinically silent, but may present with flank pain, haematuria, palpable mass, or weight loss, and rarely acute renal failure.

(a) Haematogenous spread from melanoma, prostate, breast, gastrointestinal tumours.

(b) Lung cancer metastases from lymphatic spread.

(c) Metastases to the kidney can infiltrate the perinephric space.

(a) Most commonly due to renal, adrenal or retroperitoneal tumours and metastases.

(b) Renal cell carcinoma, multiple myeloma, plasmacytoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, leukaemia, gastrointestinal stomal tumours, haemangiomas, leiomyomas and haemangiopericytomas are rare in the perirenal space and lack distinguishing features.

(c) Castleman’s disease is a rare systemic lymphoproliferative disorder.

Cystic lesions

Lymphangiomas – rare, congenital benign mesenchymal neoplasms.

Numerous intercommunicating, endothelial-lined spaces containing lymph fluid.

Usually asymptomatic, but may result in haematuria, proteinuria, hypertension and page kidney.

CT and MRI show perinephric cysts with variable peripheral or septal enhancement associated with normal kidneys.

Bechtold, R. E., Dyer, R. B., Zagoria, R. J., Chen, M. Y. The perirenal space: relationship of pathologic processes to normal retroperitoneal anatomy. Radiographics. 1996; 16(4):841–854.

Heller, M. T., Haarer, K. A., Thomas, E., Thaete, F. L. Neoplastic and proliferative disorders of the perinephric space. Clin Radiol. 2012; 67(11):31–41.

Surabhi, V. R., Menias, C., Prasad, S. R., et al. Neoplastic and non-neoplastic proliferative disorders of the perirenal space: cross-sectional imaging findings. Radiographics. 2008; 28(4):1005–1017.

8.26

Nephrographic patterns

Increasingly dense nephrogram

Increasingly faint nephrogram becoming increasingly dense over hours to days.

8.27

Renal papillary necrosis

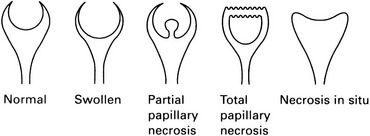

1. Normal – small kidneys with smooth outlines.

2. Bilateral in 85% with multiple papillae affected – usually a systemic cause.

3. Unilateral – usually obstruction, renal vein thrombosis or acute bacterial nephritis.

(b) Partial sloughing – a fissure forms and may communicate with a central irregular cavity.

(c) Total sloughing – the sloughed papillary tissue may:

(d) Necrosis in situ – the papilla is shrunken and necrotic but has not separated.

5. Calyces will appear dilated following total sloughing of a papilla.

6. Calcification and occasionally ossification of a shrunken, necrotic papilla. If marginal, it appears as a calculus with a radiolucent centre.

8.28

Renal-induced hypertension

8.29

Renal artery stenosis

Aetiology

1. Arteriosclerosis – 66% of renovascular causes. Stenosis of the proximal 2 cm of the renal artery; less frequently the distal artery or early branches at bifurcations. More common in males.

2. Fibromuscular dysplasia – 33% of renovascular causes. Stenoses ± dilatations which may give the characteristic ‘string of beads’ appearance. Mainly females less than 40 years. Bilateral in 60% of cases.

4. Arteritis – polyarteritis nodosa, thromboangiitis obliterans. Takayasu’s disease, syphilis, congenital rubella or idiopathic.

5. Neurofibromatosis* – coarctation of the aorta. ± Stenoses of other arteries. ± Intrarenal arterial abnormalities.

7. Aneurysm – of the aorta or the renal artery.

8. Arteriovenous fistula – traumatic, congenital or a stump fistula following nephrectomy.

9. Extrinsic compression – neoplasm, aneurysm or lymph nodes.

Signs of unilateral renal artery stenosis on ACE inhibitor renal scintigraphy

1. Low probability suggested by a normal study.

2. Intermediate probability when:

(a) Small kidney contributing < 30% of total renal function.

(b) Time to maximum activity (Tmax) ≤ 2 minutes, and shows no change following administration of ACE inhibitor.

3. High probability when unilateral parenchymal retention, indicated by

(a) A change in the 20 minute/peak uptake ratio of 0.15 or greater.

(b) Delayed excretion of tracer into the renal pelvis > 2 minutes.

(c) Increase in the Tmax of greater than 2 minutes or 40% after administration of ACE inhibitor.

4. Decreased sensitivity when bilateral renal artery stenosis, impaired renal function, urinary obstruction or long-term ACE therapy.

Hartman, R. P., Kawashima, A. Radiologic evaluation of suspected renovascular hypertension. Am Fam Physician. 2009; 80(3):273–279.

Kawashima, A., Sandler, C. M., Ernst, R. D., et al. CT evaluation of renovascular disease. Radiographics. 2000; 20:1321–1340.

Rankin, S., Saunders, A. J., Cook, G. J., et al. Renovascular disease. Clin Radiol. 2000; 55:1–12.

Soulez, G., Oliva, V. L., Turpin, S., et al. Imaging of renovascular hypertension: respective values of renal scintigraphy, renal Doppler US, and MR angiography. Radiographics. 2000; 20:1355–1368.

8.30

Renal vein thrombosis

Unilateral or bilateral. The ultrasound findings (after Cremin et al., 1991) are:

Conventional radiographic findings

Sudden occlusion

1. Large non-functioning kidney which, over a period of several months, becomes small and atrophic.

2. Retrograde pyelography reveals thickened parenchyma (due to oedema) with elongation and compression of the major calyces.

3. Arteriography shows stretching and separation of arterial branches with decreased flow and a poor persistent nephrogram. No opacification of the renal vein.

Argyropoulou, M. I., Giapros, V. I., Papadopoulou, F., et al. Renal venous thrombosis in an infant with predisposing thrombotic factors: color Doppler ultrasound and MR evaluation. Eur Radiol. 2003; 13(8):2027–2030.

Cremin, B. J., Davey, H., Oleszczuk-Raszke, K. Neonatal renal venous thrombosis: sequential ultrasonic appearances. Clin Radiol. 1991; 44:52–55.

8.31

Non-opacification of a calyx on CT or excretory urography

1. Technical factors – incomplete filling during excretory urography.

2. Tumour – most commonly a renal cell carcinoma (adult) or Wilms’ tumour (child).

3. Obstructed infundibulum – due to tumour, calculus or tuberculosis.

4. Duplex kidney – with a non-functioning upper or lower moiety. Signs suggesting a non-functioning upper moiety are:

(a) Fewer calyces than the contralateral kidney. This sign is only reliable in unilateral duplication. (Calyceal distribution is symmetrical in 80% of normal individuals.)

(b) A shortened upper calyx which does not reach into the upper pole.

(c) The upper calyx of the lower moiety may be deformed by a dilated upper pole pelvis.

(d) The kidney may be displaced downward by a dilated upper moiety pelvis. The appearances mimic a space-occupying lesion in the upper pole.

(e) The upper pole may be rotated laterally and downward by a dilated upper moiety pelvis and the lower pole calyces adopt a ‘drooping lily’ appearance.

(f) Lateral displacement of the entire kidney by a dilated upper moiety ureter.

(g) The lower moiety ureter may be displaced or compressed by the upper pole ureter, resulting in a series of scalloped curves.

(h) The lower moiety renal pelvis may be displaced laterally and its ureter then takes a direct oblique course to the lumbosacral junction.

5. Infection – abscess or tuberculosis.

6. Partial nephrectomy – with a surgical defect in the twelfth rib.

8.32

Filling defect in the renal collecting system or ureter

Extrinsic with a smooth margin

1. Cyst – see 8.18 and 8.19.

2. Vascular impression – an intrarenal artery producing linear transverse or oblique compression lines and most commonly indenting an upper pole calyx, especially on the right side.

3. Renal sinus lipomatosis – most commonly in older patients with a wasting disease of the kidney. Fat in the renal hilum produces a relative lucency and narrows and elongates the major calyces.

4. Collateral vessels – most commonly ureteric artery collaterals in renal artery stenosis. Multiple small irregularities in the pelvic wall.

Inseparable from the wall and with smooth margins

1. Blood clot – due to trauma, tumour or bleeding diathesis. May be adherent to the wall or free in the lumen. Change in size or shape over several days.

2. Papilloma – solitary or multiple.

3. Pyeloureteritis cystica – due to chronic infection. Multiple well-defined submucosal cysts project into the lumen of the pelvis and/or ureter.

8.33

Spontaneous urinary contrast extravasation

Pyelorenal backflow

1. Pyelosinus backflow – contrast extravasation from fornix rupture.

2. Pyelotubular ‘backflow’ – opacification of terminal portions of collecting ducts, so not really ‘backflow’. May be physiological. Fan-like streaks from calyx towards periphery.

3. Pyelointerstitial backflow – contrast flows from pyramids into subcapsular tubules. More amorphous than pyelotubular.

4. Pyelolymphatic backflow – dilated lymphatics. Visualization of small lymphatics draining medially.

5. Pyelovenous backflow – forniceal rupture into arcuate or interloper veins. Very rare.

8.34

Dilated calyx

With a wide infundibulum

1. Postobstructive atrophy – generally all the calyces are affected and associated with parenchymal thinning.

2. Megacalyces – dilated calyces ± a slightly dilated pelvis. ± Stones. Increased number of calyces: 20–25 (normal 8–12). Because of the large volume collecting system, full visualization during urography is delayed. Normal cortical thickness and good renal function differentiate it from postobstructive atrophy.

8.35

Dilated ureter

Obstruction

In the wall

1. Oedema or stricture due to calculus.

2. Tumour – carcinoma or papilloma.

3. Tuberculous stricture – a particular hazard during the early weeks of treatment.

4. Schistosomiasis – especially the distal ureter. ± Calcification in the ureter or bladder.

5. Postsurgical trauma – e.g. a misplaced ligature.

7. Megaureter – symmetrical tapered narrowing above the ureterovesical junction.

Vesicoureteric reflux

No obstruction or reflux

1. Postpartum – more common on the right side.

2. Following relief of obstruction – most commonly calculus or prostatectomy.

3. Urinary tract infection – due to the effect of P-fimbriated E. coli on the urothelium.

4. Primary non-obstructive megaureter – children > adults. The juxtavesical segment of ureter is of normal calibre but fails to transmit an effective peristaltic wave due to faulty development of muscle layers.

8.36

Stricture of the ureter

Inflammatory

8.37

Filling defect within the ureter

Multiple

In the wall

1. Ureteritis cystica – asymptomatic multiple, small (2–4 mm) cysts usually related to infection or calculi. Usually upper ureter.

3. Pseudodiverticulosis – associated with malignancy and 50% eventually develop uroepithelial malignancy.

4. Vascular impressions (collateral veins in IVC obstruction).

6. Multiple metastases – melanoma.

7. Suburothelial haemorrhage – usually associated with a coagulopathy. Less discrete than ureteritis cystica.

8.38

Retroperitoneal fibrosis

1. Dense retroperitoneal, periaortic fibrous tissue mass which typically begins around the aortic bifurcation and extends superiorly to the renal hila. Rarely extends below the pelvic rim.

2. Envelops the aorta and IVC, lymphatics and ureter(s) en route.

3. Demonstrable by CT (= muscle), US (hypoechoic) or MRI (low signal on T1W, high signal on T2W in the active stage, low signal on T2W in the chronic stage). Contrast enhancement in the early, active stage.

4. Ureteric obstruction is of variable severity. 75% bilateral.

5. Tapering ureteral lumen or complete obstruction – usually at L4–5 level and never extreme lower end.

6. Medial deviation of the ureters – more significant if there is a right-angled step in the course of the ureter rather than a gentle drift. The position of the ureters is frequently normal.

7. Easy retrograde catheterization of ureter(s).

8. Clinically – back pain, high ESR and elevated creatinine.

Cronin, C. G., Lohan, D. G., Blake, M. A., et al. Retroperitoneal fibrosis: a review of clinical features and imaging findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008; 191(2):423–431.

Vaglio, A., Salvarani, C., Buzio, C. Retroperitoneal fibrosis. Lancet. 2006; 367(9506):241–251.

Zen, Y., Onodera, M., Inoue, D., Kitao, A., et al. Retroperitoneal fibrosis: a clinicopathologic study with respect to immunoglobulin G4. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009; 33(12):1833–1839.

8.39

Deviated ureters

Medial deviation

1. Normal variant – 15% of individuals. Commoner in people of African–Caribbean descent, in whom bilateral displacement is also commoner.

2. Retroperitoneal fibrosis – see 8.37.

3. Retrocaval ureter – the right ureter passes behind the IVC at the level of L4. The distal ureter lies medial to the dilated proximal portion.

4. Pelvic lipomatosis – other signs suggesting the diagnosis are:

(a) Elevation and elongation of the bladder.

(b) Elongation of the rectum and sigmoid with widening of the retrorectal space.

5. Following abdominoperineal resection – the ureters are medially placed inferiorly.

8.40

Vesicoureteric reflux

Congenital (= primary reflux)

Renal scarring with UTI in 50%.

Congenital reflux – due to incompetence of vesicoureteric junction secondary to abnormal tunnelling of distal ureter through bladder. 10% of normal Caucasian babies and 30% of children with a first episode of UTI. Renal scars in up to 50%. Usually disappears in 80% but can cause end-stage renal disease in 10% of adults.

Acquired (= secondary reflux)

4. Urethral obstruction – posterior urethral valves. Mainly on left side (reflux in 33%).

5. Duplication with ureterocoele.

6. Prune-belly syndrome – almost exclusively males. High mortality. Bilateral hydronephrosis and hydroureters with a distended bladder are associated with undescended testes, hypoplasia of the anterior abdominal wall and urethral obstruction.

8.41

Filling defect in the bladder

In the wall

Shebel, H. M., Elsayes, K. M., Abou El Atta, H. M., et al. Genitourinary schistosomiasis: life cycle and radiologic–pathologic findings. Radiographics. 2012; 32(4):1031–1046.

Stenzl, A., Cowan, N. C., De Santis, M., et al. European Association of Urology (EAU). Treatment of muscle-invasive and metastatic bladder cancer: update of the EAU guidelines. Eur Urol. 2011; 59(6):1009–1018.

8.43

Bladder calcification

In the wall

1. Urothelial and squamous cell carcinoma – radiographic incidence about 0.5%. Usually surface calcification, which may be linear, curvilinear or stippled. Punctate calcification of a villous tumour may suggest chronicity. No extravesical calcification.

2. Schistosomiasis – an infrequent cause in the Western hemisphere but the commonest cause of mural calcification worldwide. Thin curvilinear calcification outlines a bladder of normal size and shape. Calcification spreads proximally to involve the distal ureters in 15%.

3. Tuberculosis – rare and usually accompanied by calcification elsewhere in the urogenital tract. Unlike schistosomiasis, the disease begins in the kidney and spreads distally. Contracted bladder.

8.45

Gas in the urinary system

Gas inside the bladder

8.46

Calcifications of the male genital tract

1. Diabetes mellitus – the cause in the vast majority of cases.

2. Chronic infection – TB, schistosomiasis, chronic UTI and syphilis.

Chen, M. Y., Bechtold, R. E., Bohrer, S. P., et al. Abnormal calcification on plain radiographs of the abdomen [Review]. Crit Rev Diagn Imaging. 1999; 40(2–3):63–202.

Rodriguez-de-Velasquez, A., Yoder, I. C., Velasquez, P. A., Papanicolaou, N. Imaging the effects of diabetes on the genitourinary system. Radiographics. 1995; 15(5):1051–1068.

8.47

Ultrasound of intratesticular abnormalities

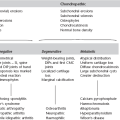

Neoplastic

1. Germ cell tumours – 95% of primary testicular tumours. 40% are of mixed histology. 8% are bilateral.

(a) Seminoma – most common testicular tumour in the adult. 40–50% of testicular germ cell tumours. 25% have metastases at presentation. Most common tumour in the undescended testis. A solid, homogeneous, hypoechoic, round or oval mass which is sharply delineated from normal testicular tissue.

(b) Embryonal carcinoma – 20–25% of germ cell tumours. More aggressive than seminoma and more heterogeneous because of necrosis, haemorrhage, cysts and calcification.

(d) Teratoma – 5–10% and most common in infants and children. Heterogeneous echo texture because of the different tissue elements present.

2. Non-germ cell tumours – usually benign. May secrete oestrogens (Sertoli cell) or testosterone (Leydig cell). Non-specific appearance but usually solid hypoechoic mass ± cystic areas.

3. Metastases – kidney, prostate, bronchus, pancreas. More common than germ cell tumours in the over 50-year-old age group. Patients with leukaemia or lymphoma may relapse in the testis and present as focal or diffuse decreased echogenicity in an enlarged testis.

Vascular

(a) Acute – presentation within 24 hours. Enlarged hypoechoic or heterogeneous testis ± hydrocoele and enlargement of the epididymis. Colour Doppler: absent testicular flow; normal peritesticular flow.

(b) Subacute or missed – presentation at 1–10 days. Colour Doppler: absent testicular flow; increased peritesticular flow.

(c) Spontaneous detorsion – colour Doppler: normal or increased testicular flow; increased peritesticular flow.

Inflammatory

1. Orchitis – generalized testicular swelling and hypoechogenicity, initially; progresses to patch focal low reflectivity. Hypoechoic areas are hypervascular. There may be swelling of the epididymis, hydrocoele and scrotal wall oedema. Complications occur in 50% – abscess formation, necrosis, haematoma and testicular atrophy.

2. Abscess – complicating epididymo-orchitis, often in a diabetic patient or those with mumps. Hypoechoic or mixed echogenic mass.

Cassidy, F. H., Ishioka, K. M., McMahon, C. J., et al. MR imaging of scrotal tumors and pseudotumors. Radiographics. 2010; 30(3):665–683.

Dogra, V. S., Gottlieb, R. H., Rubens, D. J., et al. Benign intratesticular cystic lesions: US features. Radiographics. 2001; 21:S273–281.

Kim, W., Rosen, M. A., Langer, J. E., et al. US MR imaging correlation in pathologic conditions of the scrotum [Review]. Radiographics. 2007; 27(5):1239–1253.

Mirochnik, B., Bhargava, P., Dighe, M. K., Kanth, N. Ultrasound evaluation of scrotal pathology [Review]. Radiol Clin North Am. 2012; 50(2):317–332.

8.48

Ultrasound of extratesticular abnormalities

Vascular

Varicocoele – dilated pampiniform plexus of veins posterior to the testis. In 15% of adult males and virtually always on the left side. Important to exclude a compressive retroperitoneal aetiology if the varicocoele is right-sided or does not decompress in the erect position or with a Valsalva manoeuvre.

Cassidy, F. H., Ishioka, K. M., McMahon, C. J., et al. MR imaging of scrotal tumors and pseudotumors. Radiographics. 2010; 30(3):665–683.

Kim, W., Rosen, M. A., Langer, J. E., et al. US MR imaging correlation in pathologic conditions of the scrotum. Radiographics. 2007; 27(5):1239–1253.

Woodward, P. J., Schwab, C. M., Sesterhenn, I. A. Extratesticular scrotal masses: radiologic–pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2003; 23(1):215–240.