168 Adrenal Crisis

• Adrenal crisis is an uncommon cause of shock.

• An inappropriate adrenal response may contribute to shock in patients with sepsis, trauma, myocardial infarction, and other conditions associated with extreme physiologic stress.

• The diagnosis of acute adrenal crisis may be challenging because the symptoms are often nonspecific (e.g., weakness, fatigue, gastrointestinal symptoms, abdominal, flank, or back pain).

• Laboratory findings include hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, hypoglycemia, lymphocytosis, and eosinophilia.

• Adrenal crisis may result from either primary adrenal insufficiency or secondary adrenal suppression as a result of exogenous steroids or from failure of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. In the latter, mineralocorticoid replacement is not necessary, but thyroid supplementation may be lifesaving.

• Emergency department management includes aggressive fluid resuscitation, correction of electrolyte abnormalities, maintenance of euglycemia, and administration of glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids.

• Treatment should begin with initial suspicion of adrenal crisis, not at the time of laboratory confirmation. Interventions are indicated when the cause of the shock is obscure, the patient fails to respond to volume and pressors within 1 hour, or the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency is confirmed.

Epidemiology

Most cases of primary adrenal insufficiency are autoimmune mediated, but other common causes include infection and hemorrhage. Onset is generally indolent, although acute adrenal crisis accounts for approximately 25% of all cases. Primary adrenal insufficiency has an estimated incidence of 50 per 1 million persons. Secondary insufficiency as a result of chronic glucocorticoid administration is more common than primary insufficiency in the United States; 2% of the population is estimated to have relative insufficiency that becomes manifested only at times of physiologic stress.1

Feedback Loops

Targets of Action

Mineralocorticoids act at the renal tubules to maintain Na+, K+, and water balance. Glucocorticoid subunits enter various cell nuclei and modify the expression of a wide range of genes in different organ systems (Table 168.1). Cortisol is capable of targeting the mineralocorticoid receptors at pharmacologic doses, although at physiologic levels it is converted to inactive cortisone on entering the kidney.

| FUNCTION/TARGET SYSTEM | ACTION |

|---|---|

| Metabolism |

Clinical Application

Adrenal insufficiency is classified as primary, secondary, or relative. Causes of primary insufficiency are numerous (Table 168.2). Secondary insufficiency is most commonly due to exogenous steroid withdrawal. Relative adrenal insufficiency occurs in individuals who may have normal glucocorticoid levels but exhibit an inadequate response of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis to major stress.

| CAUSE | ASSOCIATED FACTORS |

|---|---|

| Autoimmune adrenal atrophy (80% of cases) | |

| Associated endocrinopathies | Hypoparathyroidism, hepatitis, type 1 diabetes mellitus, hypogonadism, hypothyroidism |

| Infections | Disseminated tuberculosis, cytomegalovirus, histoplasmosis, human immunodeficiency virus, candidiasis |

| Genetic diseases | Congenital adrenal hyperplasia, adrenoleukodystrophy, familial glucocorticoid deficiency |

| Metastatic malignancy or lymphoma | |

| Adrenal hemorrhage | |

| Infiltrative disorders | Amyloidosis, hemochromatosis |

| Drugs | Ketoconazole, suramin |

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Patients with primary and secondary adrenal insufficiency typically have chronic complaints. Those with primary disease may exhibit weakness, fatigue, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, hypotension, hyperpigmentation, hyponatremia, and hyperkalemia. The hyperpigmentation is initially generalized and later becomes evident in the mucous membranes, palmar creases, nail beds, and nipples. Gastrointestinal disturbances are present in about half of patients with postural symptoms. Salt craving is a less common complaint. Associated endocrinopathies may complicate the initial findings (see Table 168.2).

Types of Adrenal Insufficiency

Acute Adrenal Hemorrhage

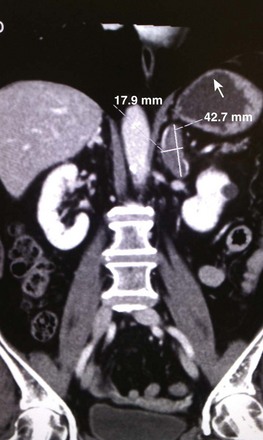

Treatment should begin on suspicion of this diagnosis. Early intervention has been shown to reduce mortality in postoperative patients and those with antiphospholipid syndrome; the timing of therapy does not appear to affect the usually high mortality associated with this condition in patients with sepsis or severe shock. Only a minority of patients will be found to have hyponatremia or hyperkalemia. The diagnosis is confirmed through imaging studies2,3 (Fig. 168.1).

Relative Adrenal Insufficiency in Critically Ill Patients*

It is estimated that approximately 2% of the U.S. population has an inadequate adrenal response to stress. The incidence of relative adrenal insufficiency in critically ill patients has been reported to be as low as 0% and as high as 77%.12,15

Diagnosis and treatment of relative adrenal insufficiency are controversial. Disagreement exists about the incidence of disease, the normal range of serum cortisol levels in response to stress or corticotropin testing in the seriously ill, the dose of corticotropin to be administered for testing, and the indications for, optimal dosing of, and desired efficacy of steroids in the critically ill.4–1315

1. There is evidence that the use of “low-dose” hydrocortisone may be beneficial for severe septic shock refractory to fluid resuscitation and vasopressors if given early in the course of the shock (within 8 hours).15

2. Delayed administration of steroids in resuscitated patients is not beneficial and may be harmful.6

Drug-Induced Adrenal Insufficiency

A number of medications may cause reversible adrenal insufficiency. Examples include ketoconazole, rifampin, phenytoin, and etomidate. Use of etomidate as an induction agent for rapid-sequence intubation (RSI) of critically ill patients is controversial. A single dose can cause relative adrenal insufficiency for up to 48 hours, but the clinical significance of this degree of suppression is unclear.14,16,17 In two retrospective and one prospective observational studies of single-dose etomidate RSI in the ED, no significant difference was found in in-hospital mortality.18–20 In a randomized study of trauma patients requiring RSI, those receiving etomidate had longer intensive care unit and hospital length of stay and more ventilator days and required more red blood cell transfusions and fresh frozen plasma.21 In an a priori substudy of the CORTICUS trial, use of etomidate in the 72 hours before study inclusion was associated with higher mortality.22 However, the survival curves did not separate until 10 to 18 days after the administration of etomidate, thus leading to questions about how the drug could have caused the deaths because relative adrenal suppression usually resolves within 72 hours of a single dose.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of adrenal crisis includes most other conditions known to cause shock (Box 168.1). These same conditions may induce relative adrenal insufficiency, and therefore their diagnosis does not exclude a concurrent adrenal crisis.

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Conditions that promote shock may induce concurrent relative adrenal insufficiency; diagnosis of one condition does not exclude a second occult disease.

Induction doses of etomidate may cause relative adrenal insufficiency for up to 72 hours after rapid-sequence intubation in critically ill patients.

Diagnostic Testing

Imaging studies may identify adrenal tumors or hemorrhage that may be responsible for the insufficiency. Incidental adrenal pathology is observed in approximately 2% of abdominal scans. Tumors may be benign or malignant, primary or metastatic.19,20

Treatment

Other Treatment Considerations

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

Do

Use a bedside glucometer and administer 50% dextrose in water as needed.

Administer a 20-mL/kg bolus of normal saline.

Begin vasopressors when shock persists despite volume resuscitation.

Check serum electrolytes, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and free thyroxine levels.

Check a random serum cortisol level.

Administer 100 mg of hydrocortisone intravenously every 6 hours.

Search for comorbid conditions, particularly causes of sepsis.

Disposition

Patients with shock or obtundation should be admitted to a critical care unit. Those who quickly respond to treatment may be considered for admission to an unmonitored floor. Patients with mild symptoms, known disease, and reliable follow-up can be treated in the emergency department and be discharged to the care of their personal physician (see Tables 168.1 and 168.2).

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Absolute lifelong compliance with outpatient medication regimens is mandatory.

Double the steroid doses during times of physiologic stress and minor illness.

Seek medical attention if nausea and vomiting occur; they may be symptoms of adrenal crisis and might prevent tolerance of needed oral medications.

Annane D, Sebille V, Charpentier C, et al. Effect of treatment with low doses of hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone on mortality in patients with septic shock. JAMA. 2002;288:862–871.

Cuthbertson BH, Sprung CL, Annane D, et al. The effects of etomidate on adrenal responsiveness and mortality in patients with septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:1868–1876.

Hildreth AN, Mejia VA, Maxwell RA, et al. Adrenal suppression following a single dose of etomidate for rapid sequence induction: a prospective randomized study. J Trauma. 2008;65:573–579.

Sprung CL, Annane D, Keh D, et al. Hydrocortisone therapy for patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:111–124.

Tekwani KL, Watts HF, Rzechula KH, et al. A prospective observational study of the effect of etomidate on septic patient mortality and length of stay. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:11–14.

1 Silva Rdo C, Castro M, Kater CE, et al. [Primary adrenal insufficiency in adults: 150 years after Addison.]. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2004;48:724–738.

2 Rao RH, Vagnucci AH, Amico JA. Bilateral massive adrenal hemorrhage: early recognition and treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:227–235.

3 Vella A, Nippoldt TB, Morris JC. Adrenal hemorrhage: a 25-year experience at the Mayo Clinic. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:161–168.

4 Briegel J, Schelling G, Haller M, et al. A comparison of the adrenocortical response during septic shock and after complete recovery. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:894–899.

5 Goodman S, Sprung CL. The International Sepsis Forum’s controversies in sepsis: corticosteroids should be used to treat septic shock. Crit Care. 2002;6:381–383.

6 Sprung CL, Annane D, Keh D, et al. Hydrocortisone therapy for patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:111–124.

7 Manglik S, Flores E, Lubarsky L, et al. Glucocorticoid insufficiency in patients who present to the hospital with severe sepsis: a prospective clinical trial. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:1668–1675.

8 Minneci PC, Deans KJ, Banks SM, et al. Meta-analysis: the effect of steroids on survival and shock during sepsis depends on the dose. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:47–56.

9 Pizarro CF, Troster EJ, Damiani D, et al. Absolute and relative adrenal insufficiency in children with septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:855–859.

10 Siraux V, De Backer D, Yalavatti G, et al. Relative adrenal insufficiency in patients with septic shock: comparison of low-dose and conventional corticotropin tests. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:2479–2486.

11 Soni A, Pepper GM, Wyrwinski PM, et al. Adrenal insufficiency occurring during septic shock: incidence, outcome, and relationship to peripheral cytokine levels. Am J Med. 1995;98:266–271.

12 Widmer IE, Puder JJ, König C, et al. Cortisol response in relation to the severity of stress and illness. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:4579–4586.

13 Yildiz O, Doganay M, Aygen B, et al. Physiological-dose steroid therapy in sepsis [ISRCTN36253388]. Crit Care. 2002;6:251–259.

14 Absalom A, Pledger D, Kong A, et al. Adrenocortical function in critically ill patients 24 h after a single dose of etomidate. Anaesthesia. 1999;54:861–867.

15 Annane D, Sebille V, Charpentier C, et al. Effect of treatment with low doses of hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone on mortality in patients with septic shock. JAMA. 2002;288:862–871.

16 De Coster R, Helmers JH, Noorduin H. Effect of etomidate on cortisol biosynthesis: site of action after induction of anaesthesia. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh). 1985;110:526–531.

17 Schenarts CL, Burton JH, Riker RR, et al. Adrenocortical dysfunction following etomidate induction in emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:1–7.

18 Baird CRW, Hay AW, McKeown DW, et al. Rapid sequence induction in the emergency department: induction drug and outcome of patients admitted to the intensive care unit. Emerg Med J. 2009;26:576–579.

19 Tekwani KL, Watts HF, Chan CW, et al. The effect of single bolus etomidate on septic patient mortality: a retrospective review. West J Emerg Med. 2008;9:195–200.

20 Tekwani KL, Watts HF, Rzechula KH, et al. A prospective observational study of the effect of etomidate on septic patient mortality and length of stay. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:11–14.

21 Hildreth AN, Mejia VA, Maxwell RA, et al. Adrenal suppression following a single dose of etomidate for rapid sequence induction: a prospective randomized study. J Trauma. 2008;65:573–579.

22 Cuthbertson BH, Sprung CL, Annane D, et al. The effects of etomidate on adrenal responsiveness and mortality in patients with septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:1868–1876.