Adolescence

Adolescent development

The research on adolescent development is vast (Erikson 1965, Croghan 2005, Lerner & Steinberg 2009). An understanding of adolescent development is essential for ED nurses in their daily practice. Adolescence is a period in the life span where the individual, previously dependent on parents and carers for his values and identity, becomes independent and, in this move towards independence, attempts to establish a new and personal identity. The key factors in this process appear to relate to the onset of puberty, i.e., the physical and emotional changes leading to sexual maturity (Bickley & Szilagyi 2003, Tortora & Grabowski 2003), and the need for independence (Smetana 2011).

Cognitively, adolescents are capable of abstract thought and understand many variables within a situation. They should also be able to understand the consequences of their actions (Bernardo & Schenkel 1995). It is a period where group identity is vital, a time of experimentation with self-image, and a time to question fundamental family values. Adolescents are pushing for independence, testing the boundaries of their existing life and, importantly, hoping to find boundaries that will aid the development of their future identity (Croghan 2005, Damon & Lerner 2008).

Caring for the adolescent in the ED

As a client group, adolescents are considered difficult to care for by the majority of nurses (Holt 1993). In the ED, many causes of adolescent attendance can be viewed as self-inflicted, e.g., as a result of alcohol or substance testing, which may render ED nurses less compassionate towards the patient. Although less an issue than before due to the ageing nursing workforce, caring for adolescents presents a particular challenge, as many nurses are just emerging from adolescence themselves. To the adolescent, these nurses may represent a more realistic role model, enhancing the opportunity for health education. This is particularly pertinent to ED nurses because there is a greater likelihood of interaction with this age group at a time when they are physically and emotionally vulnerable.

Providing ED nurses with a better idea of the process of adolescence may equip them more satisfactorily to meet their patients’ needs, which will enable them to recognize normal behaviour instead of reacting to it (Holt 1993).

Hospital staff, particularly in EDs, are quick to meet the physical needs of these patients, such as maintaining a safe environment for the drunken teenager or arresting haemorrhage in a patient with slashed wrists, but often with little regard to their emotional needs (Kuykendall 1989). An understanding of these needs, however, could reduce the risk of confrontation and diminish any perceived power struggle. The question for ED nurses is how far these needs can be facilitated within an ED without compromising the care or well-being of others in the environment. When young people are asked why they do not use health services they admit to feeling intimidated by both the service and the service providers, they dislike the times and locations, and are concerned about confidentiality and trust (Croghan et al. 2004, Croghan 2005).

The adolescent patient needs to assert his independence, but is not yet ready to cope with the implications of this. In ‘crisis’ situations, as a visit to an ED is often perceived, the ED nurse may be in a position of setting boundaries for the patient. This is not a negative action as it provides the security the adolescent indirectly seeks. All too often, however, on a busy shift, in a packed waiting room, antagonistic behaviour is allowed to escalate into confrontation, often because cues for boundaries have not been recognized by ED nurses inexperienced in adolescent development. Consistency among staff is essential. Boundaries for acceptable behaviour should be decided as a matter of policy, and this should be made clear to patients on admission while respecting their independence and individuality. In addition, Knight & Rush (1998) argue that waiting rooms should be made more ‘user-friendly’ for adolescents, ideally incorporating separate waiting and treatment areas.

Personal fable

Despite the upheaval and trauma of adolescence during this life phase, mortality is at its lowest, with the top cause of death being accident-related (Department of Health 2004). An important cause of accident in adolescence is risk-taking behaviour, not just risky sports, but minor law infringement such as failure to wear a safety belt, exceeding speed limits and experimentation with alcohol and illegal substances (Bellis et al. 2005).

A possible explanation of this is the concept of personal fable (Elkind 1967, Pahlke et al. 2010), a belief that despite risk-taking behaviour they will not be affected by life’s difficulties. This has both a positive and a negative function, and represents normal cognitive development. Positively, it allows goals to be believed in and attainable, such as dreams of success. Its negative function is that it induces risk-taking behaviour. Normally, consequences of actions are considered, but personal fable gives the security of invulnerability to consequences. This is not unique to adolescents; witness, for example, smoking and lung cancer in older people (Winkenstein 1992).

Personal fable affects not only conformity with perceived authority, but also with chronic illnesses, such as diabetes. Thinking of himself or herself as the centre of attention, the adolescent comes to believe that it is because he or she is special and unique (Alberts et al. 2007).

It is important for ED nurses to understand this concept in order to intervene in the risk-taking behaviour that can result in an ED attendance. Personal fable is there to protect the self-concept at the vulnerable time of adolescence. It allows conformity with peers despite negative consequences; for instance, the diabetic patient who presents in ED with hypoglycaemia because he has been drinking to conform with peers. The patient can ‘blot out’ the likely hypoglycaemic attack because being the same is more important. Education and support from ED nurses who understand that this behaviour is not intended to be self-destructive, but is normal adolescent experimentation, can reduce the risk of further occurrence. This perception of invulnerability may contribute to the statistic that the largest cause of adolescent death is from risk-taking – in cars, with fire arms, in water and with toxic substances. Sensitive questioning helps adolescents expose their personal myth, recognize their irrationality and induce a change in behaviour.

Risk-taking behaviour

Most common behaviours evolve from experimentation with alcohol, solvents or drugs, but it can be hard for the busy ED nurse to accept the drunk who is abusive as ‘normal’ when his behaviour is disruptive and difficult to contain. The majority of adolescents who attend ED with drug- or alcohol-related problems are not abusive, and are there because of an injury or illness related to their risk-taking behaviour. These individuals often present with their peer groups and engage in sensation-seeking behaviour, which can appear threatening to ED nurses. Adequate staffing levels and nurse skill mix, with appropriate back-up such as security officers and an incident alarm, should be available. Sensation-seeking is a normal need for experimentation and new experiences, and adolescents are prepared to take physical and social risks to attain these (Barker 1988). Despite risk-taking and sensation-seeking, most adolescents maintain conventional modes of behaviour and deviants are in the minority. EDs frequently treat adolescents as a result of risk-taking behaviour. A non-judgemental attitude is not always easy to foster, and the ED nurse must be aware of her own vulnerability and biases, as well as understanding adolescent development. This enables the nurse to treat adolescents in an appropriate manner, reduces the risk of confrontation or resentment, and respects the adolescents’ rights as individuals.

Not all adolescent risk-taking is because of a low perception of danger. Some revolves around deliberate self-harm. This is usually a cry for help from adolescents who cannot cope with the pressures of growing up. Self-poisoning is the most common reason for hospital treatment (Cook et al. 2008). Only the minority of adolescents take this route, and of these the majority are not clinically depressed. This course of behaviour is not just a result of the strains of adolescence, identity confusion, anger and guilt; it is a way of getting back at those seen as responsible for the torment, such as parents, teachers and peers. Adolescent patients often demonstrate this by a blasé attitude towards their actions. Despite low suicide intent, the danger of real harm is great because of low risk awareness. The prevalence of mental health problems among adolescents is estimated at 10–20 %, while the incidence of suicide among young men continues to increase and is linked to lifestyle behaviours such as alcohol and drug misuse, and mental health problems (Marfé 2003). Gunnarsdottir & Rafnsson (2010) found that frequent visits to the ED were significantly associated with suicide and fatal poisoning. However, up to 60 % of those who later commit suicide have attended the ED the year before the suicide but did not present themselves as cases of self-harm (Gairin et al 2003). Box 19.1 outlines the risk range for suicide among young people.

It is vital that nurses are able to distinguish between normal behaviour and abnormal distress. This can only be achieved by listening to and hearing the adolescent. Nothing should be taken at face value, as the superficial self-confidence and frequent mood changes common to teenagers can mask real and needy patients, as well as making them difficult to nurse. It is recognized that the ED is not the ideal place for in-depth discussion, but it may be the only opportunity available to the adolescent. An understanding of why the event occurred is essential before discharging the patient. The adolescent practice of ‘dumping distress’ on others via self-harm must be controlled and appropriate coping strategies learned in order to prevent further real harm. The ED nurse has a key role to play by providing constructive advice and follow-up arrangements where appropriate, not by punitive intervention (see also Chapter 15).

Substance misuse

Within the past 30 years, the worldwide drug culture has evolved dramatically, stemming from two developments. First, the major consumer generation has shifted sharply towards the young, especially adolescent and young adult males; and second, the availability of drugs has become much more widespread (Emmett & Nice 1996). While substance misuse is clearly a problem for young adults as well as adolescents, for convenience the subject will be addressed in this chapter.

In addition, the growth of the rave scene in Britain and designer drugs such as ecstasy, which appear to have become accepted by many as an integral part of relaxation and pleasure, have resulted in a culture in which substance misuse is no longer perceived as an antisocial activity, but where penalties for use and supply are severe (Box 19.2 and Table 19.1). While the ED nurse will be aware that alcohol is a major causative factor in attendances, there has been a marked increase in attendances as a consequence of other substance misuse.

Table 19.1

| Word | Meaning |

| Acid | LSD |

| Bad trip | A frightening or unpleasant LSD trip |

| Banging up | To inject drugs |

| Blow | Herbal cannabis |

| Buzzing | Feelings after use of ecstasy |

| Chill out | A period of cooling down to reduce risk of overheating from ecstasy use |

| Clean | Not using drugs |

| Coke | Cocaine |

| Crack | Freebase cocaine |

| Cut | To mix other substances with a drug to add bulk and weight |

| Detox | To withdraw from drugs under medical supervision |

| Dope | Resin and herbal cannabis |

| Doves | Ecstasy tablets with dove imprint |

| ‘E’ | Ecstasy |

| Eggs | Temazepam tablets |

| Flashback | Tripping out again sometime after LSD use. Can be days, months or even years later and is usually a bad trip (q.v.) |

| GBH | Gamma hydroxybutyrate or sodium oxybate, a liquid hallucinogenic stimulant |

| Grass | Herbal cannabis |

| ‘H’ | Heroin |

| Hash | Cannabis resin |

| High | The feeling of elation while under the influence of a drug |

| Hit | To buy or inject drugs |

| Jack up | To inject drugs |

| Jellies | Temazepam in capsule form |

| Joint | A hand-rolled cannabis cigarette |

| Magic mushrooms | Any of the species of hallucinogenic mushrooms |

| Main lining | Injecting drugs |

| Marijuana | Herbal cannabis |

| Moggies | Mogadon sleeping pills |

| Poppers | Amyl/alkyl/butyl nitrate |

| Pot | Cannabis resin |

| Rock | Freebase cocaine |

| Score | To purchase drugs |

| Shoot up | To inject drugs |

| Smack | Heroin |

| Snorting | Sniffing cocaine or other drug up the nose |

| Speed | Amphetamine |

| Stash | An amount of drugs, usually hidden |

| Trip | A hallucinogenic experience under LSD |

| Wacky bacci | Herbal cannabis |

| Whiz | Amphetamine |

| Works | Needles and syringes |

(After Emmett D, Nice G (1996) Understanding Drugs: A Handbook for Parents, Teachers and other Professionals. London: Jessica Kingsley.)

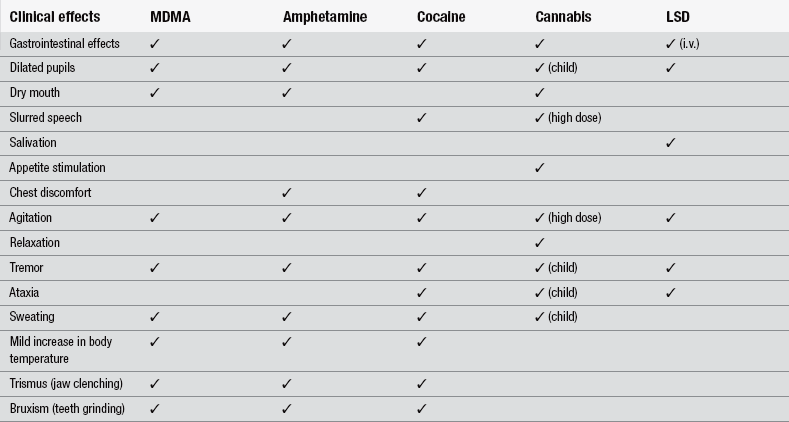

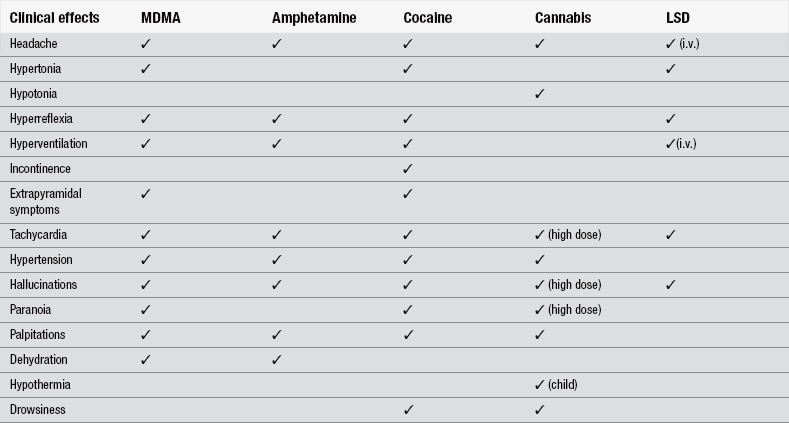

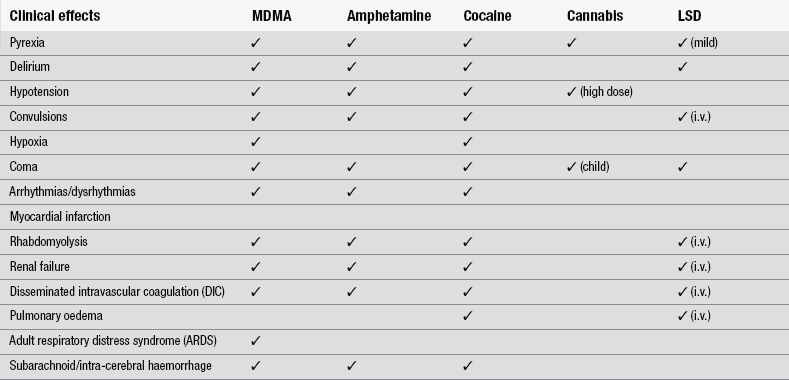

The mild, moderate and severe effects of drugs of abuse are outlined in Tables 19.2–19.4(pages 283-284).

Table 19.2

Mild clinical effects of drugs of abuse

(After Schofield E, Lawman S, Volans G et al. (1997) Drugs of abuse: clinical features and management. Emergency Nurse, 5(6), 17–22.)

Table 19.3

Moderate clinical effects of drugs of abuse

(After Schofield E, Lawman S, Volans G et al. (1997) Drugs of abuse: clinical features and management. Emergency Nurse, 5(6), 17–22.)

Table 19.4

Severe clinical effects of drugs of abuse

(After Schofield E, Lawman S, Volans G et al. (1997) Drugs of abuse: clinical features and management. Emergency Nurse, 5(6), 17–22.)

Alcohol

Despite its legal status as a controlled substance, alcohol is the most widely available and commonly used psychoactive substance among adolescents aged 12 to 16 years (Rassool & Winnington 2003). Alcohol is a central nervous system depressant. It is absorbed into the bloodstream and starts to have an effect within 5–10 minutes of drinking. The rate of absorption is affected by sex, weight, duration of drinking, nature of drink consumed, food in the stomach, physiological factors, genetic variation and rate of elimination. Paton (1994) suggested that there are 4 million heavy drinkers in the UK, of whom 800 000 are problem drinkers and 400 000 are alcohol-dependent. In recent years there has been a steady decline in the proportion of 11-to-15-year-olds who drink alcohol. The proportion of pupils who had never drank alcohol rose from 39 % in 2003 to 55 % in 2010. Less than half (45 %) of pupils aged between 11 and 15 years said that they had drunk alcohol at least once in their lifetimes. This increased with age from 10 % of 11-year-olds to 77 % of 15-year-olds. The proportion of pupils who drank alcohol in the last week fell from a peak of 26 % in 2001 to 18 % in 2009 (Fuller 2011).

In the UK, alcohol misuse and alcohol-related harm cost the NHS nearly ≤3 billion in 2006/2007 with an estimated 800 000 alcohol-attributable hospital admissions in 2006/2007 (Purshouse et al. 2010). Concomitant misuse of alcohol is also common among drug misusers. Individuals who are habituated to ethanol may have few symptoms despite massive blood ethanol concentrations. In contrast, teenagers unaccustomed to ethanol may become comatose at more modest blood ethanol concentrations (1000–2000 mg/L) (Vale 2012a). Signs, symptoms and management of alcohol intoxication are addressed in Chapter 15.

Ecstasy

For most users, ecstasy provides a feeling of euphoria, together with an increase in confidence, emotional wellness, enhanced perception of colours and lights, exhilaration and increased intimacy towards other people (Rogers et al. 2009, Meehan et al. 2010). As an amphetamine derivative, it also provides users with feelings of energy and freedom from hunger. Ecstasy use frequently leads to jaw clenching and teeth grinding (gurning), which causes tooth surface loss (Nixon et al. 2002). While adverse reactions are rare, Halpern et al. (2011) describe the most common manifestations of 52 admissions were restlessness, agitation, disorientation, shaking, high blood pressure, headache and loss of consciousness. More serious complications were hyperthermia, hyponatraemia, rhabdomyolysis, brain oedema and coma. They argue that the image of ecstasy as a safe drug is spurious. Walsh & Kent (2001) suggest that signs that should alert an ED nurse to an ecstasy-induced collapse include admission from a late night party or rave of a previously fit young person who has collapsed for no apparent reason. Some deaths have been related to cerebral oedema secondary to excess water ingestion, because the drug has an antidiuretic effect on the kidney (Braback & Humble 2001).

The control of the patient’s temperature is the key to survival, as temperatures of up to 42°C are not uncommon. Cool replacement fluids should be given at as fast a rate as the patient can tolerate and unnecessary clothing should be removed. A brisk fluid-led diuresis should be encouraged; however, if this does not control the rise in temperature then endotracheal intubation, sedation and paralysis will be instituted (Henry et al. 1992). If the temperature continues to rise, dantrolene may be used. This has muscle-relaxant properties and is used in the treatment of malignant hyperthermia following anaesthetic hypersensitivity (Jones 1993).

A central venous catheter should be inserted to measure and guide the rapid dehydration of the patient, and a urinary catheter to monitor renal function. The colour of the urine should be observed for an orange tinge that is suggestive of rhabdomyolysis, the breakdown of skeletal muscle, due to the toxic effects of released globins. Blood tests for creatinine kinase may be ordered to measure this process. Other blood tests may include regular clotting tests, and the patient should be closely observed for clinical signs of coagulation problems. The picture of disseminated intravascular coagulation, falling platelet and fibrinogen count, raised partial thromboplastin (PT) and kaolin cephalin clotting time (KCCT) is an ominous sign (Jones 1993).

Cannabis

Cannabis is the most commonly used illegal drug in the world. It is the collective term for all psychoactive substances derived from the dried leaves and flowers of the plant Cannabis sativa (Vale 2012b). It may be smoked or eaten in food. If smoked, its effects appear within 10–30 minutes and the effects have a duration of 4–8 hours. If eaten, it takes approximately 1 hour to produce its effects. Cannabis comes in three forms:

• herbal – a dried plant material, similar to coarse cut tobacco and sometimes compressed into blocks

• resin – dried and compressed sap, found in blocks of various sizes, shapes and colours

• oil – this is rare; it is extracted from the resin by the use of a chemical solvent and ranges in colour from dark green or dark brown to jet black with a distinctive smell like rotting vegetation.

After use, cannabis has the effect of creating feelings of relaxation, happiness, increased powers of concentration, sexual arousal, loss of inhibitions, increased appetite and talkativeness (Kalant 2004). Fergusson & Boden (2011) note that until relatively recently, cannabis has been viewed as a relatively harmless drug that has few adverse effects. However, in the last two decades there has been an accumulation of evidence suggesting that cannabis may have multiple harmful effects, with these effects being particularly marked for adolescent users (Hall & Degenhardt 2009). It is believed that the greater vulnerability of adolescent users may be due to the biological effects of cannabis on the developing adolescent brain (Asharti et al. 2009).

Amphetamine

Signs and symptoms of intoxication include tachypnoea, tachycardia, dilatation of pupils, dry mouth, pyrexia, blurring of vision, dizziness, loss of desire to eat or sleep, hypertension and loss of coordination (Vale 2012b). The after-effects of lethargy and fatigue can last for several days. Since tolerance develops rapidly, individual response varies greatly, and toxicity correlates poorly with dose. Amphetamines also suppress appetite and, if used regularly, can lead to substantial weight loss (Bellis et al. 2005). Fatalities are rarely reported but predominantly result from convulsions and intracranial haemorrhage. Sedatives, such as chlorpromazine, and antihypertensive agents may be used for management of the patient.

Cocaine

Snorting cocaine can cause permanent damage inside the nose, and sustained use may lead to frequent nosebleeds and recurrent sinus infections (Bellis et al. 2005). In extreme cases, use leads to exposure of the septal cartilage and nasal bones, with eventual collapse of the nose (Millard & Mejia 2001). Administering cocaine by rubbing it into the gums or other mouth-parts can cause ulcers, lesions and gingival recession (Gandara-Rey et al. 2002). Fatalities may rapidly occur secondary to convulsion, intracranial haemorrhage, intestinal ischaemia, respiratory arrest or cardiac arrhythmias. Sedatives such as haloperidol, diazepam for convulsions and antihypertensive agents may be required as part of the management regime in ED. Active external cooling is required when the patient’s temperature exceeds 41°C as cocaine impairs sweating and cutaneous vasodilation. Hypertension and tachycardia also respond to sedation and cooling (Vale 2012b).

Overdose

About 80 % of people who present to EDs following self-harm will have taken an overdose of prescribed or over-the-counter medication (Horrocks et al. 2003). A small additional percentage will have intentionally taken a dangerously large amount of an illicit drug or have poisoned themselves with some other substance. The pattern of the type of drug taken in overdose has changed in recent years, largely with changes in their availability (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health 2004).

Poisonings can be categorized into three groups: accidental, intentional and iatrogenic. Accidental poisoning most commonly occurs among young children, although death is relatively uncommon. Intentional ingestion includes recreational drug use and suicide attempts. Iatrogenic poisoning usually results from unanticipated drug interactions (Zull 1995). In cases of intentional poisoning the ED nurses should ascertain which drugs have been taken by asking the patient or attending friends or relatives (Box 19.3). The Children Act gives children under the age of 16 the right to refuse consent to treatment (Department of Health 2001). Castledine (1994) stressed the importance of establishing a good relationship with the patient, but in all cases a patient must consent if care is to be given or he can sue for assault and battery. Castledine (1994) suggested that if a patient is mentally confused due to the physical effects of illness or as a consequence of mind-altering drugs, the ED nurse could proceed to treat on the basis of urgency and necessity. Careful recording of the patient’s details and the nursing and medical staffs’ actions are important in such cases.

Conclusion

Adolescent attendance patterns highlight the need for ED nurses to understand the normal processes through which adolescents pass. Nurses can appear judgemental and less sympathetic towards a patient perceived as being responsible for his own illness (Stockbridge 1993). ED nurses can be affected by the apparent lack of compliance from adolescent patients. This can lead to paternalistic or confrontational behaviour that destroys the therapeutic relationship and exacerbates conflict. Adolescents cannot be treated wholly as adults as they lack the emotional maturity to cope with independence and still need the emotional support of parents and other carers. ED attendance is often a result of normal adolescent behaviour and ED nurses should be equipped with the knowledge necessary to provide appropriate support and education. An environment that provides boundaries, privacy and protected independence, with support, and peer support if appropriate, should be developed.

It is important to remember that psychological distress can be just as great as physical illness or trauma. ED nurses have a responsibility to consider the needs of young people as individuals. Perhaps an alteration of attitude is more important than a vast financial outlay in the improvement of adolescent care.

References

Alberts, A., Elkind, D., Ginsberg, S. The personal fable and risk-taking in early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007;36:71–76.

Ashtari, M., Cervellione, K., Cottone, J., et al. Diffusion abnormalities in adolescents and young adults with a history of heavy cannabis use. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2009;43:189–204.

Barker, P. Basic Child Psychiatry. Oxford: Blackwell; 1988.

Bellis, M.A., Hughes, K., McVeigh, J., et al. Effects of nightlife activity on health. Nursing Standard. 2005;19(30):63–71.

Bernardo, L.M., Schenkel, K.A. Pediatric medical emergencies. In: Kitt S., Selfridge-Thomas J., Proehl J.A., Kaiser J., eds. Emergency Nursing: A Physiologic and Clinical Perspective. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1995.

Bickley, L.S., Szilagyi, P.G. Bates’ Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking, eighth ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.

Braback, L., Humble, M. Young woman dies of water intoxication after taking one tablet of ecstasy. Today’s drug panorama calls for increased vigilance in health care. Lakartidningen. 2001;98(8):817–819.

Castledine, G. Ethics and law in ED. Emergency Nurse. 1994;2(1):25.

Cook, R., Allcock, R., Johnston, M. Self-poisoning: current trends and practice in a UK teaching hospital. Clinical Medicine. 2008;8(1):37–40.

Croghan, E. Supporting adolescents through behaviour change. Nursing Standard. 2005;19(34):50–53.

Croghan, E., Johnson, C., Aveyard, P. School nurses: policies, working practices, roles and value perceptions. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2004;47(4):377–385.

Damon, W., Lerner, R.M. Child and Adolescent Development: An Advanced Course. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2008.

Department of Health. Reference Guide to Consent for Examination and Treatment. London: Department of Health; 2001.

Department of Health. The National Service Framework for Children, Young People and Maternity Services. London: Department of Health; 2004.

Elkind, D. Egocentrism in adolescence. Child Development. 1967;38(4):1025–1034.

Emmett, D., Nice, G. Understanding Drugs: A Handbook for Parents, Teachers and other Professionals. London: Jessica Kingsley; 1996.

Erikson, E. Childhood and Society. Harmondsworth: Penguin; 1965.

Fergusson, D., Boden, J. Cannabis use in adolescence. In: Gluckman P., ed. Improving the Transition: Reducing Social and Psychological Morbidity During Adolescence. A Report from the Prime Minister’s Chief Science Advisor. Auckland: Office of the Prime Minister’s Science Advisory Committee, 2011.

Fuller E., ed. Smoking, Drinking and Drug Use Among Young People in England in 2010. London: NHS Information Centre, 2011.

Gairin, I., House, A., Owens, D. Attendance at the accident and emergency department in the year before suicide: retrospective study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;183:28–33.

Gandara-Rey, J.M., Diniz-Freitas, M., Gandara-Vila, P., et al. Lesions of the oral mucosa in cocaine users who apply the drug topically. Medicina Oral. 2002;7(2):103–107.

Gunnarsdottir, O.S., Rafnsson, V. Risk of suicide and fatal drug poisoning after discharge from the emergency department: a nested case-control study. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2010;27:93–96.

Hall, W., Degenhardt, L. Adverse health effects of non-medical cannabis use. Lancet. 2009;374:1383–1391.

Halpern, P., Moskovich, J., Avrahami, B., et al. Morbidity associated with MDMA (ecstasy) abuse: A survey of emergency department admissions. Human and Experimental Toxicology. 2011;30(4):259–266.

Henry, J., Jeffreys, K.J., Dawling, S. Toxicity and deaths from 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (‘ecstasy’). Lancet. 1992;340:384–387.

Holt, L. The adolescent in accident & emergency. Nursing Standard. 1993;8(8):30–34.

Horrocks, J., Price, S., House, A., et al. Self-injury attendances in the accident and emergency department: clinical database study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;183:34–39.

Jones, C. MDMA: the doubts surrounding ecstasy and the response of the emergency nurse. Accident & Emergency Nursing. 1993;1:193–198.

Kalant, H. Adverse effects of cannabis on health: an update of the literature since (1996). Progress in Neuropsychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2004;28(5):849–863.

Knight, S., Rush, H. Providing facilities for adolescents in ED. Emergency Nurse. 1998;6(4):22–26.

Kuykendall, J. Teenage traumas. Nursing Times. 1989;85(27):26–28.

Lerner, R.M., Steinberg, L.D. The Scientific Study of Adolescent Development. In Lerner R.M., Steinberg L.D., eds.: Handbook of Adolescent Psychology: Individual Bases of Adolescent Development, third ed, Hoboken New Jersey: Wiley, 2009.

Marfé, E. Assessing risk following deliberate self harm. Paediatric Nursing. 2003;15(8):32–34.

Meehan, T.J., Bryant, S.M., Aks, S.E. Drugs of abuse: The highs and lows of altered states in the emergency department. Emergency Clinics of North America. 2010;28:663–682.

Millard, D.R., Mejia, F.A. Reconstruction of the nose damaged by cocaine. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2001;107(2):419–424.

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Self-harm: The Short-Term Physical and Psychological Management and Secondary Prevention of Self-Harm in Primary and Secondary Care. The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists. 2004.

Nixon, P.J., Youngson, C.C., Beese, A. Tooth surface loss: does recreational drug use contribute? Clinical Oral Investigations. 2002;6(2):128–130.

Pahlke, E., Bigler, R.S., Green, V.A. Effects of learning about historical gender discrimination on early adolescents’ occupational judgements and aspirations. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 2010;30(6):854–894.

Paton, A. ABC of Alcohol. third ed. London: BMA Publishing Group; 1994.

Purshouse, R.C., Meier, P.S., Brennan, A. Estimated effect of alcohol pricing policies on health and health economic outcomes in England: an epidemiological model. Lancet. 2010;375:1355–1364.

Rassool, G.H., Winnington, J. Adolescents and alcohol misuse. Nursing Standard. 2003;17(30):46–52.

Rogers, G., Elston, J., Garside, R., et al. The harmful health effects of recreational ecstasy: a systematic review of observational evidence. Health Technology Assessment. 2009;13(6):1–354.

Schofield, E., Lawman, S., Volans, G., et al. Drugs of abuse: clinical features and management. Emergency Nurse. 1997;5(6):17–22.

Smetana, J.G. Adolescents’ social reasoning and relationships with parents: Conflicts and coordinations within and across domains. In: Amsel E., Smetana J.G., eds. Adolescent Vulnerabilities and Opportunities: Developmental and Constructivist Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Stockbridge, J. Parasuicide: does discussing it help? Emergency Nurse. 1993;1(2):19–21.

Tortora, G.J., Grabowski, S.R. Principles of Anatomy and Physiology, tenth ed. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2003.

Vale, A. Alcohols and glycols. Medicine. 2012;40(2):89–90.

Vale, A. Drugs of abuse (amfetamines, BZP, cannabis, cocaine, GHB, LSD). Medicine. 2012;40(2):84–87.

Walsh, M., Kent, A. Accident & Emergency Nursing: A New Approach, fourth ed. London: Butterworth Heinemann Ltd; 2001.

Winkenstein, M. Adolescent smoking. Journal of Paediatric Nursing. 1992;7(2):120–127.

Zull, D.N. Poisoning and drug overdose. In Kitt S., Selfridge-Thomas J., Proehl J.A., Kaiser J., eds.: Emergency Nursing: a Physiologic and Clinical Perspective, second ed, Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1995.