199 Addiction

• Drug abuse and alcohol abuse irrevocably change brain physiology; addiction represents a brain disorder.

• The acute manifestations of substance abuse and dependency arise from drug-specific patterns of intoxication and withdrawal.

• Acute pharmacologic detoxification is accomplished through the administration of a long-acting medication in the same category as the drug of dependence, thereby blocking withdrawal symptoms.

• Anticraving medications are psychotropic agents that reduce the desire for drugs or alcohol in detoxified patients and prevent relapse into compulsive substance abuse.

Scope, Epidemiology, and Definitions

From several viewpoints the problem is vast. Regarding alcohol, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that approximately 79,000 deaths are attributable to excessive alcohol use annually in the United States, which makes it the third leading lifestyle-related cause of death for the nation. In addition, excessive alcohol use accounts for 2.3 million years of potential life lost annually—an average of about 30 years of potential life lost for each death.1 Concerning drugs, the Substance Abuse and Mental Services Administration of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services reported that in 2009, 21.8 million Americans used an illegal drug during the month before the survey, which represents 8.7% of the population aged 12 years or older. Illegal drugs include marijuana or hashish, cocaine (including crack cocaine), heroin, hallucinogens, inhalants, and nonmedical use of prescription-type psychotherapeutics.2

Many of those abusing or dependent on alcohol or drugs, or both, disproportionately consume public health care resources, particularly emergency services. Between 1992 and 2000, alcohol-related visits to U.S. emergency departments (EDs) averaged 76 million per year, which accounted for 7.9% of the total ED visits.3 The Drug Abuse and Warning Network reported that in 2007, 1.9 million ED visits were associated with drug misuse or abuse. Although the overall number of ED visits attributable to drug misuse and abuse was stable from 2004 to 2007, ED visits involving nonmedical use of pharmaceuticals with no other drug involvement rose significantly (73%), as did the nonmedical use of pharmaceuticals with alcohol (36%).4

The societal burdens of substance abuse extend well beyond EDs. The U.S. Office of National Drug Control Policy reported that incarcerated offenders were often under the influence of drugs when they committed their offenses and that offenders often commit crimes to support their drug habit. In addition, trafficking in illicit drugs tends to be associated with the commission of particularly violent crimes.5

The cumulative economic cost of substance abuse is astounding. In 1998, alcohol abuse in the United States cost approximately $185 billion, with 47% of this cost simply being due to lost productivity at work.6 The same year, drug abuse in the United States cost $143 billion.7 When adjusted for 2010 dollars, abuse of both drugs and alcohol costs the nation $440 billion—the equivalent of 80% of all revenue raised to fund public education for grades prekindergarten through 12.8 Substance abuse is as much a public crisis for our nation as it is a personal crisis for the addict.

With substance abuse, adverse consequences occur but the pattern has not yet deteriorated into a state of dependence. More specifically, the American Psychiatric Association defines substance abuse as “a maladaptive pattern of substance use” revealed by the recurrent and significant consequences arising from repeated use of the substance: failure to fulfill major role obligations, recurrent use in situations in which it is physically hazardous, multiple substance-related legal problems, and recurrent social and interpersonal problems9 (Box 199.1). Although the consequences of use are significant, some degree of control is present.

Box 199.1

Criteria for Substance Abuse

A. A maladaptive pattern of substance use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested by one (or more) of the following occurring within a 12-month period:

B. The symptoms have never met the criteria for substance dependence for this class of substance.

From First MB, Frances A, Pincus HA. Substance-related disorders. In: DSM-IV-TR guidebook. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2004.

In contrast, substance dependence is defined as severe impairment or absence of control. Use is compulsive and occurs under the ever-present threats of tolerance and withdrawal. As stated earlier, the American Psychiatric Association more specifically defines substance dependence as a cluster of cognitive, behavioral, and physiologic symptoms indicating continued use of the substance despite significant substance-related problems9 (Box 199.2).

Box 199.2

Criteria for Substance Dependence

1. Tolerance, as defined by either of the following:

2. Withdrawal, as manifested by either of the following:

3. The substance is often taken in larger amounts or over a longer period than was intended.

4. There is a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control substance use.

5. A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the substance (e.g., visiting multiple doctors, driving long distances), use the substance (e.g., chain smoking), or recover from its effects.

6. Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of substance use.

7. The substance use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychologic problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance (e.g., current cocaine use despite recognition of cocaine-induced depression, continued drinking despite recognition that an ulcer was made worse by alcohol consumption).

From First MB, Frances A, Pincus HA. Substance-related disorders. In: DSM-IV-TR guidebook. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2004.

Tolerance is reflected by the “need for increasing amounts of the substance to achieve intoxication or desired effect … or diminished effect with continued use of the same amount of the substance.”9

Withdrawal is a physiologic response manifested by the characteristic “withdrawal” syndrome for the particular substance or use of the same or a closely related substance to relieve or avoid such symptoms.9

Pathophysiology and Anatomy

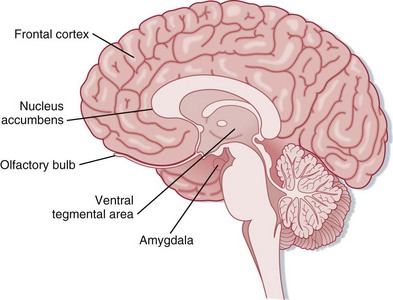

Addiction changes brain physiology, thus prompting designation of this condition as a brain disorder.10 Addictive substances alter multiple neurotransmitter pathways within the brain, including N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors, as well as the endogenous opioid, serotonin, and dopamine systems.11 Changes particularly occur within the mesolimbic system of the brain. Projecting from the ventral tegmental area to the nucleus accumbens, olfactory tubercle, frontal cortex, and amygdala, the mesolimbic system is regarded as the “reward center” of the brain12 (Fig. 199.1). These neurocircuits presumably evolved to reward survival-enhancing behavior, including productive familial and social interactions, reproduction, and other such behavior. Some suggest that mesolimbic dopamine is a direct mediator of reward, whereas others emphasize that dopamine signals an interest in reward or the expectation that reward is forthcoming. Either way, evidence suggests that the common reinforcing and incentive effects of addictive substances are substantially mediated by increasing extracellular dopamine within the mesolimbic system. On an elementary level, this drug-induced efflux of dopamine is pleasurable.10

See Figure 199.1, Mesolimbic Dopaminergic System, online at www.expertconsult.com

As addicts and clinicians mutually recognize, artificially inducing the mesolimbic system with drugs and alcohol for these pleasant effects is accompanied by grave shortcomings. Neurochemical pleasure circuits, overwhelmed by excessive stimulation, adapt by desensitizing.13 Evaluation by multiple disciplines, including anatomic, behavioral, biochemical, and electrophysiologic studies, commonly shows that dopamine neurons function insufficiently in addicts. A hypodopaminergic state develops.10 The dopamine deficiency associated with acute withdrawal is manifested clinically as acute dysphoria, depression, irritability, and anxiety. Neurochemically, baseline levels of the “reward” neurotransmitters are depressed.12 The traditional social and behavioral stimulants of the mesolimbic system that function effectively in the nonaddictive state, such as family and positive affirmation from work or friends, become inadequate to generate a significant perception of pleasure. Drugs and alcohol are the sole stimuli sufficient to activate the impaired mesolimbic neurocircuits and generate pleasure.13 Yet even though the baseline mesolimbic system remains hypodopaminergic in addicts, the system remains hyperresponsive to abused drugs and alcohol, thereby conferring long-lasting vulnerability even after extensive periods of abstinence.10 The most promising avenues of treatment for addicts are pharmacologic agents aimed at restoring these dopaminergic neurocircuits.10

Not all individuals are equally susceptible. Those with risk-taking and novelty-seeking traits favor the use of addictive drugs. Psychiatric conditions, in particular, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, are associated with increased risk for substance abuse and dependency. A dual diagnosis of substance abuse and mental disorder has especially unfavorable implications for both management and outcome.14

Genetic factors clearly increase the risk for addiction. First-degree relatives of alcoholics (e.g., parents, siblings, children) have a threefold to fourfold greater prevalence of alcohol abuse than the general population does.15 Men whose parents were alcoholics have an increased likelihood for alcoholism even when adopted at birth and raised by nonalcoholic parents.14 Genetic factors, as revealed by studies in identical twins, account for approximately half of the risk for alcohol abuse.15

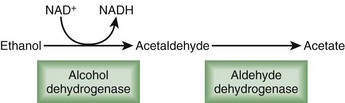

Some of this genetic predilection for addiction is expressed through enzymatic variants. For instance, highly active forms of aldehyde dehydrogenase increase alcohol metabolism and decrease the negative side effects of alcohol intake, thereby enhancing consumption and addiction (Fig. 199.2). In contrast, less active variants of aldehyde dehydrogenase (i.e., the ALDH2*2 allele initially detected in eastern Asian populations) allow accumulation of acetaldehyde, the toxic intermediary by-product of alcohol metabolism. Sensitivity to alcohol increases with a subsequent reduction in the rates of alcoholism.16 Genetic influence is also expressed through neurotransmitter variants. Neuropeptide Y, a 36–amino acid peptide neurotransmitter, regulates appetite, anxiety, and reward. A functional Lue7Pro polymorphism in the neuropeptide Y gene increases the risk for alcohol dependence by 7.3%, primarily in European Americans.17 Although the initial use of a drug or alcohol is a willful act, for those predisposed to abuse or dependency, some if not most of what follows is progressively beyond their control.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Acute intoxication with central nervous system depressants—alcohol, sedatives, hypnotics, and anxiolytics—is characterized by dysfunctional behavioral and neurologic changes. Individuals suffer mood swings and impaired social or occupational functioning. Poor judgment prevails, often reflected by inappropriate sexual or aggressive behavior. Neurologic dysfunction occurs along a clinical spectrum determined by the degree of intoxication and ranges from slurred speech, incoordination, and unsteady gait to impairment of memory and attention, stupor, and coma (Box 199.3). In contrast, acute withdrawal from central nervous system depressants is manifested as physiologic and behavioral agitation. Psychomotor distress can be significant, with transient visual, tactile, or auditory hallucinations. Patients experience autonomic hyperactivity, evident as tachycardia and diaphoresis. Nausea and vomiting may be prevalent, as well as hand tremors. Generalized seizures can occur. Mentally, emotionally, and physically miserable, such patients cannot function.9

Box 199.3

Diagnostic Criteria for Intoxication with Alcohol, Sedatives, Hypnotics, or Anxiolytics

A. Recent use of a sedative, hypnotic, or anxiolytic

B. Clinically significant maladaptive behavioral or psychologic changes (e.g., inappropriate sexual or aggressive behavior, mood lability, impaired judgment, impaired social or occupational functioning) that developed during or shortly after sedative, hypnotic, or anxiolytic use

C. One (or more) of the following signs developing during or shortly after sedative, hypnotic, or anxiolytic use:

D. The symptoms are not due to a general medical condition and are not better accounted for by another mental disorder

From First MB, Frances A, Pincus HA. Substance-related disorders. In: DSM-IV-TR guidebook. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2004.

Though also central nervous system depressants, opiates confer somewhat unique states of intoxication and withdrawal. Because of the rapid but variable degrees of tolerance that develops to opiates, incremental doses are required to achieve euphoria. However, the unreliable concentration of opiates in street drugs complicates attempts by addicts to self-administer a specific dose. Overdosage frequently results in extreme drowsiness and potentially coma and death from respiratory depression (Box 199.4). In contrast, opiate withdrawal is an extremely unpleasant, conscious experience. Patients experience severe dysphoria, diaphoresis, vomiting, and diarrhea.9

Box 199.4

Diagnostic Criteria for Opioid Intoxication

B. Clinically significant maladaptive behavioral or psychologic changes (e.g., initial euphoria followed by apathy, dysphoria, psychomotor agitation or retardation, impaired judgment, or impaired social or occupational functioning) that developed during or shortly after opioid use

C. Pupillary constriction (or pupillary dilation as a result of anoxia from a severe overdose) and one (or more) of the following signs developing during or shortly after opioid use:

D. The symptoms are not due to a general medical condition and are not better accounted for by another mental disorder

From First MB, Frances A, Pincus HA. Substance-related disorders. In: DSM-IV-TR guidebook. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2004.

The signs and symptoms of acute intoxication with central nervous system stimulants—cocaine, amphetamines, and sympathomimetics—are determined by the pattern, route, and amount of drug used, as well as the specific agent. Intermittent “binge” use is often accompanied by euphoria and heightened psychomotor and autonomic activity (e.g., tachycardia, hypertension, seizures, cardiac arrhythmias, chest pain). Chronic daily users have a contrasting scenario. Psychomotor depression and affective blunting may be present, often in the setting of hypotension, bradycardia, and respiratory insufficiency (Box 199.5). Withdrawal from central nervous system stimulants occurs after a period of heavy and prolonged use. The withdrawal symptoms of dysphoria, suicidal ideation, extreme fatigue, and hypersomnia are the antithesis of those of acute intoxication.9

Box 199.5

Diagnostic Criteria for Cocaine and Amphetamine Intoxication

A. Recent use of cocaine or amphetamine

B. Clinically significant maladaptive behavioral or psychologic changes (e.g., euphoria or affective blunting; changes in sociability; hypervigilance; interpersonal sensitivity; anxiety, tension, or anger; stereotyped behavior; impaired judgment; impaired social or occupational functioning) that developed during or shortly after the use of cocaine or amphetamine

C. Two (or more) of the following developing during or shortly after cocaine or amphetamine use:

D. The symptoms are not due to a general medical condition and are not better accounted for by another mental disorder

From First MB, Frances A, Pincus HA. Substance-related disorders. In: DSM-IV-TR guidebook. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2004.

Emergency physicians often encounter a particularly challenging if not frustrating clinical scenario arising from addiction—drug-seeking activity. Those seeking drugs may engage in “doctor shopping” by visiting multiple outpatient clinics, EDs, and pain management clinics to obtain prescriptions for controlled substances. At times, “scam” situations are presented, such as chronic toothaches, lost or stolen prescriptions, or multiple drug allergies. While recognizing the need to evaluate each situation separately, the physician must be particularly vigilant when patients insist on specific controlled substances, self-assert a high tolerance to medications, or issue veiled threats. Additional clues to drug-seeking behavior are listed in Box 199.6. When in doubt, the signs and symptoms can often be validated through contact with the patient’s personal physician, review of recently issued prescription drugs with the patient’s pharmacist, or perusal of previous medical records.18

See Box 199.6, Drug-Seeking Behavior, online at www.expertconsult.com

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of substance abuse–related disorders is limited (Box 199.7). Hypochondriasis and somatization disorders are generally difficult to distinguish from true addiction in a single ED encounter. Pseudoaddiction describes behavior similar to that of addiction but arising from mismanaged pain. Pseudoaddiction patients are highly focused on obtaining medications, though usually through appropriate routes. They may be “clock watchers” and be focused on the scheduled delivery of approved analgesics. When suspecting a disruption in their expected regimen, a pseudoaddict may become deceptive or overly dramatic in attempts to ensure treatment. As noted, distinguishing between addicts and pseudoaddicts is challenging in an isolated encounter. In a broader perspective, however, pseudoaddicts generally function well once their pain is treated effectively, usually with long-acting opioids.19

See Box 199.7, Differential Diagnosis of Substance-Related Disorders, online at www.expertconsult.com

Diagnostic Testing

In contrast to the increasing reliance on technology in diagnosing other medical disorders, the clinical interview remains the best tool for the diagnosis of substance-related disorders. Patients should be questioned about the quantity and frequency of use in an empathetic, nonjudgmental manner. Problems and symptoms current and past should be addressed, including any other family members with substance-related disorders. A number of screening tools are available: CAGE, the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST), the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), and the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST). These interview tools consist of anywhere from 4 to 28 “yes or no” or multiple choice questions and require from 30 seconds to 7 minutes to complete.20

Treatment and Disposition

The treatment goals of substance abuse, in particular, substance dependency, are twofold: detoxification and prevention of relapse (Table 199.1). These objectives are approached through two strategies: pharmacotherapy and behavioral therapy.

| AGENT | DETOXIFICATION | ANTICRAVING |

|---|---|---|

| Ethanol |

* Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved as an anticonvulsant but potentially effective in preventing alcohol relapse.

† Use in Britain; not currently FDA approved for use in the United States.

‡ FDA approved for another indication.

Detoxification is a pharmacologic process. The principle of pharmacologic detoxification is straightforward. Patients receive a long-acting medication in the same category as the drug of dependence, thereby blocking withdrawal symptoms. The dosage of this medication is gradually reduced under medical supervision.21

Alcoholics are detoxified with benzodiazepines: lorazepam, diazepam, and chlordiazepoxide. These drugs act by decreasing the hyperautonomic state of alcohol withdrawal by facilitating inhibitory GABA transmission.22 Simultaneous therapy is directed not at alcohol withdrawal per se but rather at frequently associated comorbid conditions, such as malnutrition, and includes thiamine, multivitamins, folate, and magnesium.

Opiate detoxification is managed with two classes of medications: opioid agonists and α2-agonists. The time-tested opioid agonist of broadest use is methadone. The 36-hour half-life of methadone far exceeds the 3- to 4-hour half-life of heroin. Methadone may be prescribed only by maintenance programs approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and designated state authorities. However, methadone may be used by physicians for temporary maintenance or detoxification if an addicted patient is admitted to the hospital for an illness other than opioid addiction. Methadone may also be used in an outpatient setting when administered daily for a maximum of 3 days while a patient awaits admission to a licensed methadone treatment program.23 Buprenorphine, a partial µ-receptor opioid agonist, has a half-life of 20 to 25 hours and may be prescribed by physicians who have received a waiver by the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). α2-Agonists are a commonly used detoxification therapy for mild to moderate opiate withdrawal symptoms in the ED. Activation of presynaptic α2 receptors inhibits sympathetic outflow.24 Currently, only clonidine is available in the United States. However, lofexidine, another α2-agonist similar to clonidine but with a lower incidence of associated hypotension, has been used effectively in Britain for opioid detoxification for more than a decade. Lofexidine will probably be submitted to the FDA for approval based on recent clinical trials.25

Prevention of Relapse

In the past 25 years, a new class of psychoactive medications has emerged that show substantial promise in the treatment of addiction disorders. These “anticraving” medications reduce desire for the drug or alcohol in detoxified patients and deter relapse into compulsive substance abuse.21

Three medications have been approved by the FDA for the prevention of alcohol relapse: naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram. As noted earlier in the section “Pathophysiology and Anatomy,” alcohol increases extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens.21 In mice pretreated with naltrexone, an opioid µ-receptor antagonist, the alcohol-induced increase in dopamine is blocked. These mice do not self-administer alcohol.26 Similarly, in a study of 99 alcoholic men, naltrexone-treated subjects reported reduced alcohol craving and drinking and decreased alcohol-related euphoria. Relapse rates in naltrexone-treated men were also significantly lower.

Naltrexone can be administered in two formats: an oral daily dosage of 50 mg and depot intramuscular injections of 380 mg every 4 weeks. A metaanalysis of 18 trials of naltrexone for alcohol dependence demonstrated a decrease in the risk for relapse with naltrexone when compared with placebo (relative risk, 0.64; 95% confidence interval, 0.51 to 0.82), as well as a reduction in craving and return to drinking and an increase in time to the first drink. The effect size for reducing relapse was modest (number needed to treat, 7).27

Not unexpectedly, daily dosing regimens with naltrexone limit compliance. Depot injections of naltrexone every 4 weeks both enhance compliance and establish more stable therapeutic levels. Three extended-release injectable formulations of naltrexone are available: Vivitrol, Naltrel, and Depotrex.27

Acamprosate was approved by the FDA in 2004 for the maintenance of abstinence in detoxified alcohol-dependent patients. The neurochemical effect of acamprosate is attributed to modification of glutamate neurotransmission.27 Administered orally three times daily, acamprosate is less convenient than either oral or depot naltrexone. In addition, the impact of acamprosate on abstinence is unclear. Several largely positive clinical trials in Europe were contradicted by three negative clinical trials in the United States and Australia. Thus the clinical benefits of acamprosate are equivocal.27

Disulfiram blocks aldehyde dehydrogenase, an enzyme fundamental to alcohol metabolism. When someone consumes alcohol while taking disulfiram, acetaldehyde, an intermediate and relatively toxic by-product, accumulates 5- to 10-fold relative to normal circumstances. A most disagreeable clinical consequence, the “disulfiram reaction,” develops. Diaphoresis, headache, dyspnea, hypotension, flushing, palpitations, nausea, and vomiting can all occur. Individuals taking disulfiram have poor compliance because of the unpleasantness of this effect.21 Disulfiram is administered at 500 mg/day for 1 to 2 weeks, followed by an average maintenance dose of 250 mg/day. Reviews of efficacy show mixed results.27

Topiramate, though approved by the FDA as an anticonvulsant, has shown promise in preventing alcohol relapse. A multisite U.S. trial showed that topiramate reduced the percentage of heavy drinking days when compared with placebo (43.8% versus 51.8%) in 371 men and women with alcohol dependence over a period of 14 weeks. Topiramate was also more effective than placebo in improving the secondary outcomes of percent days abstinent and number of drinks per day.28

Additional agents under investigation for the prevention of relapse include baclofen, nalmefene, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and ondansetron, among others.29

Three medications have been approved by the FDA for the prevention of relapse from opiates: methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone. Methadone and buprenorphine act as complete (methadone) or partial (buprenorphine) µ-receptor agonists. Conceptually, methadone and buprenorphine provide long-term replacement therapy for the brain disorder of addiction, comparable with the use of prednisone in patients with adrenal insufficiency or levothyroxine in those with hypothyroidism. Naltrexone, a µ-receptor antagonist, blocks the euphoric effects of opioids. Compliance is relatively poor with naltrexone.21

Unfortunately, no medications have been approved by the FDA for the prevention of relapse from cocaine addiction. However, five agents that are FDA-approved for other indications have been found in randomized, controlled trials to be effective for cocaine addiction. Topiramate, modafinil, and vigabatrin affect glutamate and GABA neurotransmission. The mechanism of two others, disulfiram and propranolol, is unknown.21

Clinical trials have yet to demonstrate any clear therapeutic options for prevention of relapse from methamphetamine.30

Disposition

Multiple behavioral therapies are available to diminish the likelihood of relapse. Contingency management is based on the operant conditioning principle that behavior resulting in positive consequences is more likely to recur. Patients meeting specific drug-free goals receive incentives or rewards. Cognitive behavioral and skills training emphasizes a functional analysis of drug use by taking into account the antecedents and consequences of drug use. Addicts then learn to identify situations at high risk for drug use and relapse. Through rehearsal and role-playing, addicts develop strategies to either avoid such situations or cope effectively. Motivational enhancement therapy (MET) seeks to develop the individual’s inner drive for change. Couples and family treatment takes into account the familial and social systems in which substance use commonly occurs. Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) provides a facilitative form of behavioral therapy that consists of a 12-step program based on self-assessment and fellowship activities.31

As noted earlier, pharmacologic and behavioral therapies appear to be most effective when used together. To assess this assumption, from 2001 through 2004 the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) compared the efficacy of acamprosate, naltrexone, and placebo in combination with behavioral treatments among 1383 recently alcohol-abstinent volunteers (median age, 44 years) from 11 U.S. academic sites in the nationwide clinical study COMBINE (Combining Medications and Behavioral Intervention). Patients receiving medical management with naltrexone, combined behavioral intervention (CBI), or both fared better on drinking outcomes. Acamprosate showed no evidence of efficacy, with or without CBI. No combination produced better efficacy than did naltrexone or CBI alone in the presence of medical management. Placebo pills and meeting with a health care professional had a positive effect above that of CBI during treatment. Naltrexone with medical management could be delivered in health care settings, thus serving alcohol-dependent patients who might otherwise not receive treatment.32,33

Treatment Efficacy

Alcohol

To better understand the value of particular therapies for alcoholism, the NIAAA initiated Project MATCH (Matching Alcoholism Treatment to Client Heterogeneity) in late 1989. A total of 1726 patients were recruited at treatment facilities throughout the United States. Two parallel cohorts represented the primary formats of treatment: outpatients recruited directly from the community and “aftercare” patients consisting of those who had just completed an inpatient or intensive day hospital treatment program. The three treatment arms included MET, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and a Twelve-Step Facilitation (TSF) program grounded on the 12-step principles of AA but based on professionally delivered individualized therapy rather than therapy in peer groups.34

Project MATCH revealed several notable findings. Most significantly, linking patients to specific behavioral therapies added little to treatment outcome. This disputed the notion that specific patient–behavioral treatment matching is essential for effective treatment of alcoholism. In addition, when compared with their status before treatment, drinking and negative consequences declined regardless of which of the three treatments the participants received. In the outpatient group, 10% more patients receiving TSF achieved continuous abstinence than did those receiving the other two treatments (24% for TSF as opposed to 15% for CBT and 14% for MET).34

Opiates

Since 1964, methadone has been the mainstay of opiate pharmacotherapy. Studies have shown that moderate- to high-dose treatment with methadone (80 to 120 mg) reduces or eliminates opiate use in outpatient settings. A placebo-controlled study of methadone involving 100 male narcotic-addicted subjects evaluated both long-term retention in treatment and criminal activity. After initial stabilization of acute withdrawal symptoms with methadone, subjects were randomized to treatment with either methadone or placebo. At 32 weeks, the placebo group had a 10% retention rate as compared with a 76% retention rate in the methadone group. At 156 weeks, 2% of the control group and 56% of the methadone group were still in treatment. Approximately one third of subjects in the methadone group continued to use illicit opiates. Felonious behavior was also positively affected by methadone. Criminal activity in the placebo group, measured by conviction per man-month, was double that of the methadone group.35

1 http://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/alcohol-use.htm.

2 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: national findings (Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-25, DHHS Publication No. SMA 10-4586). Rockville, Md. 2010.

3 McDonald A, Wang N, Camargo C. US emergency department visits for alcohol-related diseases and injuries between 1992 and 2000. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:531–537.

4 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2007: national estimates of drug-related emergency department visits. Rockville, Md. 2010.

5 http://www.whitehousedrugpolicy.gov/publications/factsht/crime/index.html.

6 Harwood H. Updating estimates of the economic costs of alcohol abuse in the United States: estimates, update methods, and data. Report prepared by The Lewin Group for the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2000. Based on estimates, analyses, and data reported in Harwood H, Fountain, D, Livermore G. The economic costs of alcohol and drug abuse in the United States 1992. Report prepared for the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services. NIH Publication No. 98-4327. Rockville, Md: National Institutes of Health; 1998.

7 Office of National Drug Control Policy. The economic costs of drug abuse in the United States, 1992-1998. Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President (Publication No. NCJ-190636); 2001.

8 http://www.usgovernmentspending.com/year2010_US.html#usgs30220.

9 First MB, Frances A, Pincus HA. Substance-related disorders: In: DSM-IV-TR guidebook. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2004.

10 Melis M, Spiga S, Diana M. The dopamine hypothesis of drug addiction: hypodopaminergic state. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2005;63:101–154.

11 http://www.uptodate.com/online/content/topic.do?topicKey=substan/7100&selectedTitle=3~150&source=search_result#H12.

12 Koob G. Neurobiology of addiction: toward the development of new therapies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;909:170–185.

13 Helmuth L. Addiction: beyond the pleasure principle. Science. 2001;294:983–984.

14 Camí J, Farré M. Drug addiction. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:976.

15 http://www.uptodate.com/online/content/topic.do?topicKey=substan/7100&selectedTitle=3~150&source=search_result#H9.

16 Nestler EJ. Genes and addiction. Nat Genet. 2000;26:277–281.

17 Lappalainen J, Kranzler HR, Malison R, et al. A functional neuropeptide Y Leu7Pro polymorphism associated with alcohol dependence in a large population sample from the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:825–831.

18 Parran T, Jr. Prescription drug abuse. A question of balance. Med Clin North Am. 1997;81:971–973.

19 Hansen GR. The drug-seeking patient in the emergency room. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2005;23:349–365.

20 Miller NS, Brady KT. Addictive disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2004;27:xi–xviii.

21 O’Brien CP. Anticraving medications for relapse prevention: a possible new class of psychoactive medications. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1423–1431.

22 Chiang C, Wax PM. Withdrawal syndromes. In: Ford MD, Delaney KA, Ling LJ, et al. Clinical toxicology. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2001:585.

23 http://www.uptodate.com/online/content/topic.do?topicKey=substan/6738&selectedTitle=1~60&source=search_result#H5.

24 Gonzalez G, Oliveto A, Kosten TR. Combating opiate dependence: a comparison among the available pharmacological options. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5:713–725.

25 http://www.uptodate.com/online/content/topic.do?topicKey=substan/6738&selectedTitle=2~4&source=search_result#H7.

26 Roberts AJ, McDonald JS, Heyser CJ, et al. mu-Opioid receptor knockout mice do not self-administer alcohol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293:1002–1008.

27 http://www.uptodate.com/online/content/topic.do?topicKey=substan/2267&selectedTitle=13~150&source=search_result.

28 http://www.uptodate.com/online/content/topic.do?topicKey=substan/2267&selectedTitle=1~40&source=search_result#H21.

29 http://www.uptodate.com/online/content/topic.do?topicKey=substan/2267&selectedTitle=1~40&source=search_result#H26.

30 Cretzmeyer M, Sarrazin MV, Huber DL, et al. Treatment of methamphetamine abuse: research findings and clinical directions. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003;24:267–277.

31 Carroll KM, Onken LS. Behavioral therapies for drug abuse. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1452–1460.

32 Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, et al. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence. JAMA. 2006;295:2003–2017.

33 NIAAA Launches COMBINE Clinical Trial. National Institute of Health News Release March 8. http://www.nih.gov/news/pr/mar2001/niaaa-08.htm, 2001. Available at January 19, 2006

34 . Patient Treatment Matching—Alcohol Alert No. 36-1997. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. No. 36. April 1997. Available at pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/aa36.htm January 9, 2006

35 Kreek MJ, Vocci FJ. History and current status of opioid maintenance treatments: blending conference session. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;23:93–105.