CHAPTER 9 Adaptation to General Health Problems and Their Treatment

This chapter reviews (1) how children learn to distinguish being sick from being healthy, what causes one to feel sick, and how to get better; (2) how sick children’s understanding of health and illness states is similar to and yet different from that of healthy children; (3) how children adapt to or cope with stress; (4) how chronic illness stresses the child and family unit; (5) children’s competency in medical decision making; (6) the importance of proactively transitioning chronically ill young adults to adult care; and (7) children’s understanding of death. The crucial role of the cognitive developmental sequence in determining what pediatric patients understand and why they respond as they do to the need for adherence to treatment regimens is evident in virtually every aspect of any medical encounter. Time and repetition remain key elements in fostering understanding of illness and promoting healthy behaviors.

CHILDREN’S UNDERSTANDING OF HEALTH AND ILLNESS

In 1986, the First International Conference on Health Promotion defined child health as “the extent to which individual children or groups of children are able or enabled to: a) develop and realize their potential; b) satisfy their needs; and c) develop the capacities that allow them to interact successfully with their biological, physical, and social environments.”1 In 1997, the World Health Organization defined health as a state of complete physical, social, and mental well-being.2

What is the child’s conceptualization of illness? A number of investigators surveying children with a variety of illness types and in a variety of cultures3–9 have consistently found that the child’s understanding of illness is a stepwise process that evolves in a systematic and predictable sequence. A useful, although by no means the only, framework for understanding this evolution is Piaget’s theory of cognitive development.10,11 According to this paradigm, both biological and cognitive maturation and the accumulation of experiences facilitate a progression to sequentially more sophisticated stages of understanding. Salient characteristics of each stage include the progressive ability to engage in logical (operational) thought, to separate internal realities (wishes, desires, thoughts) from the external world, and to distinguish other people’s points of view from one’s own.

Children with almost any type of chronic illness have a more sophisticated understanding of disease, especially their own, than do healthy children, and their knowledge base can expand quickly with increasing experience with the disease.12–14 Similarly, children in the general population have a better understanding of “everyday”-type illnesses—which they or a family member or friend have experienced—than they do of less common or unusual illnesses.15 However, even younger children (e.g., those in kindergarten through sixth grade) can benefit from appropriate, developmentally based instruction about relatively complicated conditions, such as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), without engendering fear of contracting or being harmed by the illness.5,16,17 Thus, acquired knowledge plays a role in children’s conceptual development that augments gains in understanding purely from the maturational process or experience.

Understanding of illness in children as young as 4 to 6 years includes such dimensions as identity (what the illness is, including labels and symptoms); consequences (the short- and long-term effects); time frame (how long the illness usually lasts or how long it will take to get better); cause (factors contributing to the onset of the illness); and cure (actions needed to become well again). Young children’s understanding of these dimensions of illness is similar to, although less mature and informed than, that of adults and appears to be an important influence on health-related beliefs and behavior.

Although preschool-aged children have limited understanding of their role in illness causation, most understand that they have a role to play in the remediation of illness, probably because they have already been asked to do so (e.g., take medication, drink lots of fluids, stay in bed). Thus, if clinicians desire to involve children in health decisions, they should provide appropriate, structured choices regarding the various treatment options available to encourage a patient’s willing participation.15

Symptoms are the outward manifestation of disease and serve as the cues that enable children to identify and recognize illness. Studies of how children understand illness have typically been based on the conceptual complexity, factual content, and accuracy of their responses about causation and transmission.4,5,18 Brewster12 outlined a three-stage sequence of conceptual development in children’s understanding of illness causation: (1) illness is caused by human action, (2) illness is caused by germs, and (3) illness is caused by physical weakness or susceptibility. Perrin and Gerrity3 reinterpreted these findings as follows: (1) illness is the consequence of transgression against rules, (2) illness is caused by the mere presence of germs in the environment, and (3) illness may have many causes, including the body’s particular response (host factor) to a variety of external agents that either cause or cure disease.

Piagetian Framework of Illness Conceptualization

Piaget19 demonstrated that children exhibit a system of logic that is fundamentally different from that of adults, as they try to understand and explain basic concepts such as space, time, number, and causality. As the child’s understanding of the world increases, the system of logic follows a developmental sequence that appears to be independent of specific cultural differences, although it is influenced by age, particularly developmental age, and by experience. In a landmark 1980 study, Bibace and Walsh11 investigated the relationship between children’s assimilation of their illness experience and Piaget’s stages of cognitive development, especially causal reasoning. In particular, they investigated the degree of differentiation between self and others as a major determinant of differences in children’s conceptions of health and illness.

PRELOGICAL CONCEPTUALIZATIONS

According to Piaget,20 children between the ages of about 2 and 6 years are egocentric and unable to separate themselves from their environment. They are also anthropomorphic and bound by magical thinking. These characteristics typically result in explanations of causality that are undifferentiated, logically circular, and superstitious and that reflect the immediate spatial or temporal cues that dominate their experience. Juxtaposition in time or space is interpreted as having a cause-and-effect relationship (syncretism). They are unable to understand processes and mechanisms because they focus solely on one aspect of a situation or an object without attending to the whole. (For example, if a child of this age looks at two pencils of equal length that are aligned so that one pencil is placed below and an inch to the right of the upper pencil, the child will designate the lower pencil as longer if he or she focuses on the right side and will designate the upper pencil as longer if he or she focuses on the left side.) Children of this age also have little understanding of being sick, except as this is told to them (“Your face feels warm; you should go to bed” or, conversely, “You don’t have a fever; go out and play”). Whereas getting sick may be seen as the consequence of a misbehavior (“If you had worn your boots as I told you to, you wouldn’t have gotten sick”), getting well is seen as the result of following certain rules (“You’ll get better if you stay in bed and drink lots of orange juice”).21 This just-world view (good behavior is rewarded and bad behavior is punished, or people get what they deserve) occurs when fairness judgments predominate over physical causality and is referred to as immanent justice. In the youngest children, the outcome of an act is more important than intent (breaking three dishes while helping to clear the dinner table is worse than breaking one dish when climbing up to a cupboard to get some forbidden candy stored there).

Two types of explanation about illness are characteristic of prelogical thinking: phenomenism and contagion. Phenomenism is considered the most developmentally immature explanation of illness causality. In this conceptualization, the child is unable to explain how spatially or temporally remote phenomena, which they ascribe as the causes of illnesses, actually have that effect. Example: “How do people get colds?” “From the sun.” “How does the sun give you a cold?” “It just does, that’s all.”11 Contagion theory explains the cause of illness as people or objects that are proximate, but not touching, the person. The link explaining how the illness is transmitted is magical. Example: “How do people get colds?”… when someone else gets near you.” “How?” “I don’t know—by magic, I think.”11

Raman and Gelman,22 investigating children’s understanding of transmission of genetic disorders and contagious illnesses, found that children as young as early school age were able to distinguish genetic disorders from contagious illnesses in the presence of kinship cues (e.g., “Someone else in the family has this condition.”). In contrast, in the presence of contagion cues (e.g., “Someone coughed in your face.”), preschoolers selectively applied contagious links primarily to contagious illnesses. When they were presented with descriptions of novel illnesses, children were most likely to infer that permanent illnesses were probably transmitted by birth parents rather than by contagion. Thus, even at the late preoperational stage, children appear to recognize that not all disorders are transmitted exclusively by germ contagion.

CONCRETE OPERATIONAL CONCEPTUALIZATIONS

Children aged about 7 to early adolescence are able to distinguish between self and others.19 Unlike younger children, who have a univariate view of the world, older children are able to understand phenomena from multiple points of view and can understand relationships between events or objects (the pencils from the previous example are understood to be of equal length, just placed differently in space). By manipulating objects, the older child is also able to understand reversibility. However, hypothesis formation is not yet possible. In terms of understanding health and illness, the older child is likely to see external agents causing illness; getting well is a passive experience in which body systems play little or no role.

Two explanations are particularly salient: contamination and internalization. Contamination explanations are characterized by beginning to understand the cause of an illness and how this cause might act. Example: “How do people get [colds]?” “You’re outside without a hat and you start sneezing. Your head would get cold—the cold would touch it—and then it would go all over your body.”11 Internalization refers to understanding that the cause of illness (person, object) might be outside the body, but it causes an illness that is inside the body by being incorporated within it. Typically, the child has little understanding of organs and organ systems. Example: “How do people get colds?” “In winter, they breathe in too much air into their nose, and it blocks up the nose.” “How does this cause colds?” “The bacteria get in by breathing. Then the lungs get too soft [child exhales], and it goes to the nose.” “How does it get better?” “Hot fresh air, it gets in the nose and pushes the cold air back.”11

FORMAL OPERATIONAL CONCEPTUALIZATIONS

Formal operational explanations tend to be physiological or psychophysiological. Physiological explanations place the source or nature of an illness within specific body parts or functions. Example: “What is a cold?” “It’s when you get all stuffed up inside, your sinuses get filled up with mucus….” “How do people get colds?” “They come from viruses.… Other people get the virus and it gets into your bloodstream.”11 Psychophysiological explanations are among the most sophisticated responses. Building on the physiological model, the child recognizes that thoughts or feelings can affect how the body functions. Example: “What is a heart attack?” “It’s when your heart stops working right. Sometimes it’s pumping too slow or too fast.” “How do people get a heart attack?”… You worry too much. The tension can affect your heart.”11

SICK CHILDREN’S UNDERSTANDING OF ILLNESS

Children process information about their own illnesses according to a predictable sequence of cognitive maturation12 that is similar to their understanding of illness in general. They understand first human causation (especially doing something “wrong”), followed by the germ theory, the differentiation of causes depending on the type of condition, and finally an interactional model, in which physical or psychological susceptibility and external factors act together to cause illness. Although this sequence is no different from that in healthy children, having an illness can influence the rapidity with which children pass through the various stages of understanding. Crisp and colleagues14 found that experience with a chronic illness (present for 3 or more months, involving repeated hospitalizations, or interfering with normal childhood activity) increases children’s understanding at various ages; this increase may be especially prominent at the transition points between Piaget’s stages of cognitive functioning. However, this greater sophistication does not necessarily generalize beyond the child’s specific condition. For example, children with cancer do not necessarily know more than their healthy peers about the common cold.14 Krishnan and associates23 actually raised the question about whether children with a chronic disease are resistant to learning about new medical information that has no bearing on their own illness.

What Is Being “Sick”?

An important issue is the child’s perception of what is considered illness in the context of self and what is not. Note, for example, the following exchange with an 8-year-old boy with Legg-Perthes disease, published by Brewster:12 “How does someone get sick?” “Because they touch something. I mean because they eat junk.” “How did you get sick?” “I didn’t.” “Why did you come?” “My leg got hurt.” “How?” “I was born with a leg like this.” “How did it happen?” “I don’t know.” For this boy, having Legg-Perthes disease fits into the same category of personal physical characteristics as having brown eyes or curly hair: “I have it, it’s a fact of my life.” In contrast, being “sick” is a state other than baseline, and the most common sicknesses are viral infections, especially gastroenteritis or colds. When children of this age think about illnesses, they are most likely to consider those conditions that they, their family, and their friends have experienced that preclude them from their usual participation in activities of daily living (e.g., school, playing).

Did I Cause My Illness?

Despite an advanced understanding of their own disease, children may experience egocentric or magical thinking, especially about causation. In fact, adults may also experience such egocentrism (“I know that my child’s cancer is caused by bad white blood cells, but I wonder if I did something to cause it”). Brewster12 found that such magical thinking was especially likely to occur at times of great stress, when temporary regression to earlier developmental stages is common. This regression results in a state of “cognitive dissonance.” For example, children (and adults) may maintain a notion of personal culpability (sense of guilt) despite “knowing better” and understanding logical explanations for illness causation.

In the mid-20th century, Gardner24 hypothesized that guilt (acknowledgment of “something bad I did”) served to protect parents of children with severe physical illnesses against the feelings of helplessness that might otherwise overwhelm them were they to believe that their child’s condition was merely the result of random chance. In this context, Gardner urged health care personnel to be wary of assuaging guilt feelings of parents—and older children, especially adolescents—too quickly, if such feelings serve a useful purpose in the search for meaning. Eliminating a defense is hazardous without some reasonable expectation that a more constructive concept will take its place. In the final analysis, the clinician’s hearing and understanding what the patient or parent is saying and why are more important than the patient’s or parent’s hearing and understanding what the clinician is saying.

The Evolution of the Concept of Being Sick

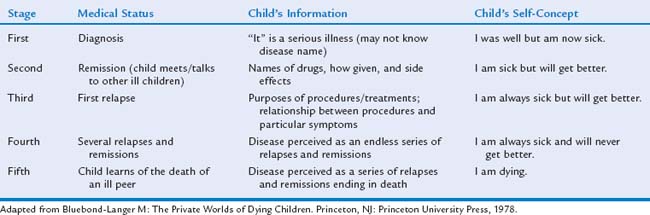

Table 9-1 provides insight into the evolution of sick children’s thinking about health—and death—as their illness progresses. This particular schema is most useful when there is an abrupt onset of “disease,” so that the moment of diagnosis is a discrete event coinciding with a perceived state of illness. This is different for children with cystic fibrosis, for example, when the “diagnosis” typically occurs as the result of a laboratory study performed in the context of ongoing concern about the child’s growth or general state of health, rather than in response to an acute event that is easily recognized as signaling being “sick.” In this instance, the moment of diagnosis is less clear and the transition from “maybe” being sick to “really” being sick is more problematic. For children who experience a gradually progressive, almost imperceptible decline over long intervals, the series of discrete steps exemplified by cancer relapse and remission is not as obvious. Over time, however, the general principles of increasing experience, interaction with others in similar circumstances, and the growing understanding that certain skills or functions are being either lost or never fully developing, serve as the basis for these patients’ advanced knowledge about their illness.

Unlike children with cancer or other progressively deteriorating conditions, children with non-life-threatening handicapping conditions typically do not progress to the fifth stage (see Table 9-1). Instead, they habituate to the fourth stage. Instead of seeing themselves as “sick,” they are more likely to see themselves as “different.” In fact, children with such conditions as spina bifida, seizure disorder, hemophilia, or cerebral palsy reject the notion of sickness unless they have an illness (e.g., a cold, gastroenteritis) that any member of the general population would consider a sign of being sick.

Hidden Disabilities

Children with such “hidden” disabilities as diabetes, sickle cell anemia, dyslexia or other learning disability, or a psychiatric disorder such as anxiety face unique challenges. In the optimal scenario, such children develop a self-perception that positively integrates their experience of disability and enables them to cope with their limitations and adjust to the expectations of society.25 Unfortunately, this is a cognitive process that frequently does not become manifest until late adolescence or young adulthood, if ever. In the meantime, dependence on peers and diminished acceptance by the peer group, which can be particularly cruel to anyone who is perceived as different, can result in years of social isolation that is either imposed by the group or self-imposed.

Disclosure to Friends

For other children, whether to disclose their illness can become an inescapable issue when asked to participate in sleepovers and class trips. Such interventions as insulin injections, chest physiotherapy, or colostomy bags may be impossible to hide. Most children are surprised when their friends and classmates are, aside from curious, also supportive.

The Role of Health Education

Health care personnel often assume that providing information to a child will lead to greater understanding and, as a result, better adherence to treatments. Yet this outcome is rarely realized, for several reasons: (1) children have their own conceptualization of what is happening to them; (2) their ability to assimilate information may be limited by their general level of cognitive functioning; and (3) other factors, particularly emotional factors, may further impede understanding.12

Although many educational interventions have been implemented in attempts to increase adherence to treatment regimens, only modest improvements have been found in certain clinical outcomes. A meta-analysis of educational programs for children with asthma revealed small to moderate gains in lung function, activity level, school attendance, and self-efficacy and decreases in emergency room visits.26 Such modest findings are fairly typical for educational interventions, especially among children with chronic but nondisabling conditions. Current approaches must be modified in order to realize significant benefits.

In contrast, children and adolescents diagnosed with potentially life-threatening illnesses such as cancer are interested in knowing about their disease and treatment.1 Knowledge appears to reduce anxiety and depression and to increase self-esteem. For teenagers, increased knowledge leads to more trusting relationships with staff and enhanced coping with painful procedures. The process of information sharing is not a one-time event but rather extends over a series of sessions that address the child’s status and any anticipated changes in treatment.

CHILDREN’S ADAPTATION TO STRESS

Coping, or adaptation to stress, entails managing emotions, thinking constructively, regulating and directing behavior, controlling autonomic arousal, and acting on both social and physical environments to alter or decrease stressors.27 Both mental and physical health are strongly influenced by exposure to and ability to cope with stress.

Eisenberg and colleagues28 defined three aspects of coping, or self regulation: regulation of emotion (emotion-focused coping or emotional regulation); regulation of the situation (problem-focused coping); and regulation of emotionally driven behavior (behavior regulation). Compas and colleagues27 add that the child’s or adolescent’s developmental level both contributes to and constrains the repertoire of mechanisms available for coping. Thus, infants have the capacity to self-soothe (e.g., sucking), a primitive, automatic, reflexive behavior. Conscious, volitional self-regulation does not appear until the development of the concept of intentionality, representational language, metacognition, and the capacity for delay. These are characteristics that first begin to emerge during the late preoperational or early concrete operational stages and are unlikely to be seen until early school age.

Rudolph and colleagues,29 when considering a child’s reaction to a stressor, identified three particular portions of that reaction: the coping response (the intentional physical or emotional action in response to a stress); the coping goal (the objective or intent of the coping response, which is usually to reduce the aversive effects of the stressor); and the coping outcome (the specific consequences of the person’s deliberate, volitional attempts to reduce the stress). Attempts at coping may become maladaptive when the consequences of the coping response meet the initial coping goal but create a more severe stressor in its place. For example, a child might develop a headache in anticipation of a math test. The headache is severe enough that the child stays home from school. Absence results in not having to take the math test (realization of primary goal) but also causes the student to miss a key lesson in social studies, which then causes him or her to fall behind in that subject. Unless the student makes up the work quickly and does extra studying (added stress), it is likely that another headache will occur at the time of the social studies test. Over time, the headache becomes recurrent because of sequential isolated stress and then, eventually, progresses to chronic, persistent pain because of anxiety about poor academic performance in many areas (overwhelming stress).

Coping responses can be characterized according to a number of different types. Behavioral versus cognitive coping distinguishes between external modes of coping (e.g., overt, observable actions such as seeking information or support; holding someone’s hand) and internal modes of coping (e.g., constructive self-talk such as “I can do this”; diversionary thinking). Another type distinguishes between problem-focused coping (eliminating or altering a distressing situation; constructive problem solving) and emotion-focused coping (regulating one’s emotional reaction to a situation: positive reframing, acceptance). Primary versus secondary coping highlights the differences between altering the situation and maximizing the person’s fit to the current situation in ways that are similar to problem-versus emotion-focused coping. Approach versus avoidance might be described as information seeking versus information avoiding or attention versus distraction. For example, during venipuncture, some children want to see the needle, watch the needle being inserted, and calculate how long it will take for the tube to be filled with blood; other children want to look away and do not want to be told when the needle will be inserted, preferring to carry on a loud, unrelated conversation with a parent. Finally, another way to look at coping style is what Field and associates30 described as sensitizers versus repressors. Sensitizers exhibit higher levels of anxiety before procedures, whereas repressors tend to be more fearful and disruptive during procedures and rate themselves as more distressed after procedures. Sparse research focuses on the efficacy of different coping approaches or whether it is more desirable for a child to have a few successful coping strategies31 or many coping strategies in order to be prepared for a novel stressor.32

In summary, children’s coping is a complex phenomenon. We should view coping not in terms of single, mutually exclusive categories of responses but rather as a multifaceted process. Crouch33 developed a multidimensional model, COPE, that classifies coping along four separate, non-orthogonal dimensions: (1) control—primary versus secondary; (2) orientation (toward or away from the stressor)—attention versus distraction; (3) process (specific categories of coping thoughts and behaviors)—information seeking, support seeking, emotional regulation, and direct action; and (4) environmental match—the degree of match or mismatch between the child’s coping goals or responses and the parent’s or other caregiver’s method of facilitating coping. This classification is a reminder that giving the child some level of control over how he or she will handle the stressor is crucial for successful coping. Furthermore, we can promote constructive coping by helping the child at his or her level of understanding and incrementally molding the response to become increasingly adaptive.

CHILDREN’S UNDERSTANDING OF DEATH

Until the mid-1970s, it was unusual for children to be given information about their illness. In particular, little was said about potentially fatal illness. Pioneering work by Spinetta,34,35 among others, led to the discovery that children who were uninformed about their illness, its treatment, and the prognosis often felt lonely and isolated and were subject to frightening fantasies about their condition. These findings have led to greater openness, more developmentally appropriate explanations, and frequent invitations to the child to ask questions and express wishes and worries. Greater awareness of how children understand their illness and the unnecessary stress imposed by silence has led to better understanding of how children conceptualize death in general and how terminally ill children conceptualize their own death specifically.

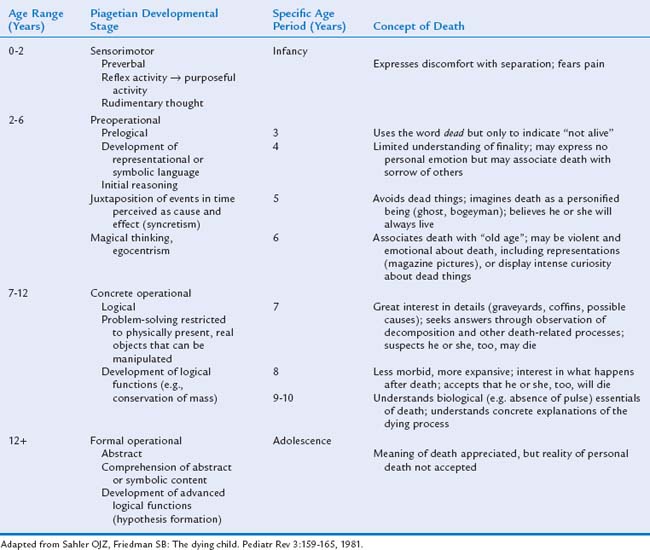

Development of the Concept of Death

The acquisition of four basic cognitive concepts frames the stages of understanding death: irreversibility (death is permanent), inevitability or universality (all living things eventually must die), finality or nonfunctionality (dead people no longer have experiences or feelings), and causality (why a death occurs).36

A Piagetian framework helps explain observable behaviors that reflect cognitive understanding of death, like that of health and illness (Table 9-2). This, like all stage-based frameworks, represents only a guide to common behavior in the general population of children. The time at which children display these behaviors is clearly influenced by personal experience, such as the death of a family member, friend, or pet and by their specific education about death.

Children at the sensorimotor stage have limited language skills that are typically “instrumental,” used to make known simple wants and needs (e.g., “ba-ba” for bottle, or “go car” to signal going for a ride). Their emotions are expressed primarily through behaviors such as laughing, tugging at someone or something, or crying. Children of this age are uncomfortable with separation from familiar people or surroundings, as evidenced by separation anxiety and stranger anxiety. They react to pain by crying, because they do not understand that they might have some control over the intensity of their experience of pain, despite past successful experiences with such approaches as distraction.

Terminally Ill Children’s Perceptions of Their Own Death

Clarifying the terminally ill child’s concerns can be emotionally difficult for the caregiver who understands the finality of death and the pain of loss. Adults may believe that discussion will provoke, rather than allay, children’s fear and anxiety. However, speaking directly with a dying child is the most effective way to explore the range of issues that preoccupy such children. Some children are most concerned with the rituals surrounding their own death. Questions such as “Can I take Barbie with me?” “Will Dr. X and my nurses come to the funeral?” or “What will heaven be like?” are seeking reassurance about the continuation of what is familiar and comfortable. Comments such as “Don’t cry a lot, Daddy” reflect the child’s concern for the welfare of others. Questions such as “Will you keep my pictures in the album?” are efforts to gain assurance that their lives have been meaningful and that they will be remembered.

CHRONIC ILLNESS AS A PARADIGM OF STRESS

Diagnosis of a significant chronic health condition in child of any age has a profound effect on the entire family. Level of adaptation is directly related to the success of the various coping mechanisms available to each individual. Parental adjustment to chronic and life-threatening illness in children remains an important focus of psychosocial investigation because parental adjustment influences not only parent but also child-patient and sibling adaptation within the dynamic family system.37–39

Parental Adjustment to a Child’s Chronic Illness

In studies of parental adjustment to childhood cancer, investigators have documented increased levels of emotional distress, typically heightened anxiety and depression.40–45 However, mothers and fathers appear to differ in their responses. For example, Barrera and colleagues40 found higher levels of distress among mothers of children with cancer than among mothers of children with acute illnesses, and Noll and associates46 similarly reported greater distress in mothers of children with cancer than in mothers of classmates without a chronic illness but found no differences for fathers. Additional studies have confirmed that mothers of children with cancer experience higher levels of distress than do fathers.44,47 Most longitudinal studies suggest that any increased levels of distress in parents of children with cancer attenuate to normal levels over 6 to 12 months,48–51 although some have revealed no significant decreases up to 18 months after diagnosis.44,52

Studies of the effects of being persistently exposed to a major stressor, such as cancer in their children, suggest that mothers are especially at risk for posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS), with an incidence as high as 40%.38,53–59 Overall, it appears that mothers of children with cancer represent a group prone to high levels of emotional distress and that the period after their child’s diagnosis and the initiation of treatment may be particularly traumatic.51,60

Dolgin and colleagues61 reported on a multisite, longitudinal study, monitoring more than 200 English-speaking and newly immigrated Spanish-speaking mothers for 6 months, beginning about 8 weeks after diagnosis of cancer in their children. These mothers received no intervention except “usual psychosocial care” (mental health, financial, and education assessments typically provided at the cancer center where their children were treated). As a group, the mothers displayed moderately elevated levels of negative affectivity (anxiety, depression) and PTSS during the period immediately after diagnosis. These levels were higher than those reported for general populations of adults without a child with cancer and also higher than those reported for mothers of long-term survivors.38 Distress declined steadily, in line with previous studies documenting moderate initial levels of distress that diminish over the year after diagnosis.49–52,62

Dolgin and colleagues61 were able to identify specific trajectories of maternal adjustment over time, with three distinct patterns emerging from the sample as a whole: mothers whose initial distress levels were comparatively low and remained so over time (stable-low); mothers who exhibited moderate levels of initial distress that remained so over time (stable-moderate); and mothers who had very high initial distress levels that declined over time (early-high). Trajectory analyses may help target those most likely to benefit from intervention efforts.

PREDICTORS OF PARENTAL ADJUSTMENT

Studies of predictors of parental adjustment to childhood cancer often focus on such variables as social support and parental coping style.47,48,63 In Dolgin and colleagues’61 report, maternal personality traits (i.e., neuroticism) and problem-solving ability (to be discussed) were significant predictors of initial distress levels, as well as the rate of improvement over time. Mothers with higher levels of neuroticism and poorer problem-solving skills had initially increased negative affectivity and PTSS.

The model presented by Dolgin et al61 suggests that quantifiable personality characteristics (neuroticism, extroversion, agreeability, problem-solving ability) in combination with readily available sociodemographic data (marital status, ethnicity, and education level) can be meaningful predictors of how a mother will adjust. Developing robust screening tools that incorporate identified predictors can assist in targeting intervention services and allocating clinical resources. Between one third and one half of the total sample reported on by Dolgin and colleagues had a stable-low distress adjustment trajectory, which suggests that delayed distress, or late-onset adjustment difficulties, are unlikely to occur in parents who are doing well initially, if their children continue to do well (the children of the mothers in this study were all clinically stable). Targeting individuals with a stable-moderate or early-high distress trajectory for intervention would be clinically most sensible, as well as resource efficient.

Interventions designed to improve parental adaptation to childhood cancer are increasingly available. Kazak and associates64 developed a promising four-session intervention integrating cognitive-behavioral and family therapy approaches to reduce PTSS in childhood cancer survivors and their parents. The report by Dolgin and colleagues61 demonstrated the benefits of an eight-session cognitive-behavioral intervention based on the five steps of problem-solving therapy (“Identify the problem”; “Determine your options”; “Evaluate your options, and pick the one most likely to succeed in your hands”; “Act”; and “See whether it worked”).65

The Stress of Procedural Pain

HOW CHILDREN PERCEIVE THE INTENT OF PROCEDURES

A child’s conceptualization of the value, function, and consequences of the procedure has implications for the coping process.29 A child who appreciates the secondary gain of expressing feelings of pain may view it as an opportunity to garner sympathy or a reward, whereas a child who views a medical procedure as unnecessary may recount all the dangers and side effects; a child who understands the benefits may focus on the positive aspects of the procedure and its potential results (perhaps indicating that no further [painful] treatment is required).

Children’s understanding of the intent of medical procedures and the role of medical personnel parallels their changing concept of illness and reflects their general understanding of intentionality and social roles. In the very earliest stage, the child perceives medical treatment or procedures as punishment for some undesired behavior. This is much the same as the child’s perception that illness is a punishment. In the next stage, children perceive painful procedures as something done to help them, but they are unable to infer the good intent of the care providers. Thus, they typically believe that the providers will know that the procedure is painful only if the child cries, which typically elicits a response like “I’m sorry. I don’t mean to hurt you.” In the final stage, children are able to understand that the intent is to help them and that providers are aware of the pain they are causing (“because they were kids once”) and that providers would not inflict the pain if they could avoid it. Children also develop the perception, frequently carried into adulthood, that others who have not suffered as they have cannot fully understand their distress (“Sometimes I feel nobody understands what’s really happening to me, I think because I’ve had it and other people don’t, so they don’t know”).12

THE EXPERIENCE OF PROCEDURAL PAIN

Fordyce66 distinguished four basic facets of a pain episode: nociception (physiological signal that alerts the central nervous system to an aversive stimulus), pain (the sensory perception of the stimulus), suffering (the affective reaction to the stimulus, such as fear or distress), and pain behavior (the person’s actions in response to the stimulus).

The experience of pain is unique to each individual. What may be merely a minor inconvenience to one child may be debilitating to another. Until improvements were made in nonverbal and indirect techniques to assess pain, clinicians believed that children had a lower sensitivity to pain perception than did adults, commonly attributed to immaturity of the nervous system or high levels of resilience. These assumptions frequently led to underestimates of perceived pain and undertreatment.67 In fact, current evidence suggests that neonates experience more pain sensitivity than do older age groups.68 Furthermore, although critically ill neonates may demonstrate little visible response to pain, they mount impressive hormonal, metabolic, and cardiovascular responses to invasive procedures.69

In early investigation of the possible neurophysiological repercussions of early exposure to painful stressors, Barr and colleagues70 hypothesized that repeated exposure may redirect the growth of neural pathways and result in a “nociceptive neural architecture that renders the individual pain vulnerable or pain resilient.” Specifically, an increase in dendritic branching may accompany the experience of pain, producing a permanently lowered pain threshold. Anand and Scalzo,71 reporting on the effects of repeated pain experiences in animal models, demonstrated that the plasticity of the neonatal brain responds by altering pain sensitivity and anxiety levels. These alterations result in an increased occurrence of, for example, stress disorders in adults. Among children, pain, fear, and separation anxiety all are likely to contribute to the child’s perception of invasive medical procedures as bodily threats and even punishments.

Inadequately managed procedural pain associated with common childhood experiences (e.g., immunization, venipuncture, laceration repair) can have long-term, negative effects on future pain tolerance and pain responses.72 These findings have contributed to increased attention to pain management in all clinical settings, including the emergency department72,73 and the inpatient hospital setting,74 with the use of both pharmacological and nonpharmacological approaches.29,31,32,75–77

Most children do not habituate to repeated painful procedures.78 Although sedation may remove the memory of the event, the pain itself is nonetheless experienced. Furthermore, it distorts thinking and may interfere with the child’s understanding during the procedure. Of even more concern is that sedation has been associated with airway obstruction, hypoxia, and apnea, especially when used with other central nervous system depressants (e.g., opiates). Such side effects as simple pooling of secretions can be life-threatening in children who have impaired pulmonary functioning, such as those with cerebral palsy who undergo painful Botox injections.79

Recollection of Pain

Despite advances in pediatric pain management, misconceptions persist. Some providers believe that children do not remember pain or do not experience pain as intensely as do adults. In fact, children as young as age 2 years can recall a painful procedure (e.g., voiding cystourethrogram) up to 6 months later. As expected, older children provide more complete and accurate reports than do younger children. The specific behaviors recalled by children are influenced by various factors: crying during a procedure is inversely correlated with the ability to report correct information; procedure-related talk is positively associated with correct information; and distraction is negatively associated with the accuracy of recall.80

Children as young as 5 years can provide detailed information about their pain, using a variety of descriptors. They can reliably discriminate among the sensory (quality, duration), affective (tension, fear), and evaluative (intensity) components of pain.81 By school age, children can recall painful experiences, understand the nature of pain causality, and associate pain with certain feelings, such as fear, anxiety, and embarrassment.82 However, children also have conceptual deficiencies in understanding. For example, few school-aged children can identify how pain is transmitted (e.g., “It’s a signal sent by a nerve”)82 or identify a beneficial function (e.g., a warning about being burned by a hot stove).83 Children at this age are, however, well aware of the secondary gain derived from having pain (e.g., missing school, avoidance of responsibilities). Children and teenagers functioning at the formal operational level show advanced understanding of the physiological, biological, and psychosocial aspects of pain.84

COPING WITH PROCEDURAL PAIN

Several child-specific variables moderate or affect the strength of coping responses to procedural pain, including age or developmental level, gender, prior experience,29 and temperament.

Age/Developmental Level

Younger children are more likely to use loud verbalizations (crying, screaming) and whole body contortions (squirming); older children are likely to exhibit verbal expressions of pain and greater muscular rigidity. Increasing age is also associated with increasing information seeking, higher levels of direct problem solving, lower levels of problem-focused avoidance, more cognitive self-distraction, and less rumination about escape strategies.29

Gender

Girls are likely to report more pain and anxiety when coping with medical procedures.85 Girls are also more likely to cry, cling, and seek emotional support, whereas boys are more likely to be uncooperative. These differences are probably the result of typical socialization processes that encourage boys to adopt stoic attitudes about pain and encourage girls to be more passive and affective in their expression of pain. This responsiveness to social expectations tends to increase these gender differences as children mature into adolescents.29

Prior Experience

Repeated pain may have significant negative effects on brain development. Whether children beyond early infancy are able to habituate to painful procedures is unclear. In some instances, experience may facilitate the purposeful development of adaptive skills such as information-seeking strategies86 to reduce current anxiety. In other instances, especially among younger children, responses to feared stressors are more likely to be automatic and conditioned. Thus, unpleasant or painful memories of experiences may increase the negative emotions associated with procedures and interfere with coping.87

In general, the quality of past experiences may be a more accurate predictor of coping response than is the quantity. For example, negative experiences appear to be predictive of parental, staff, and observer ratings of children’s increased anxiety and distress during medical examinations.88 However, it is also possible that there is some expectation, perhaps unconscious, on the part of parents or staff about how the child will react, and this can become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Temperament

Temperament may also play a role in how a child copes with painful procedures. Psychologically, temperament is classically defined as an inborn dispositional difference in behavioral style and self-regulation or variability in individual behavioral responses to external stimuli.89 Physiologically, temperament is conceptualized in terms of individual differences in reactivity to stress and focuses on, for example, cardiovascular and neuroendocrine responsiveness (heart rate, blood pressure, vagal tone, cortisol levels).90 Children with temperaments characterized by higher levels of behavioral or physiological reactivity, lower levels of adaptability, and lower thresholds for behavioral or physiological responsiveness to stimuli demonstrate higher levels of distress when confronted with medical stressors and seem to prefer coping responses that decrease their perception of the stressor (avoidance, distraction). From a physiological viewpoint, such coping responses may downregulate a child’s reaction to the stressor. Children with less reactive and more adaptable temperaments, who demonstrate lower levels of distress, may be able to take better advantage of coping responses that involve direct confrontation with the stressor (information seeking, observation).29

PREPARATION OF THE CHILD FOR PAINFUL PROCEDURES

Reviews of how best to prepare children for painful procedures focus primarily on two approaches: the use of pharmacological therapies91,92 and the use of nonpharmacological, complementary, or alternative therapies.93 In fact, as advocated by Kazak and associates,94 a combination of the two approaches is most likely to achieve maximal benefit for the majority of children. The primary goal should be adequate pain control with the minimum amount of sedation while helping the child develop a sense of mastery from self-regulation through distraction (e.g., music, puppets), education about the procedure, or mind-body (e.g., self-hypnosis) techniques. Studies have repeatedly demonstrated cognitive-behavioral therapies, in particular, to be effective in pain management.95 (See Chapter 21 for more details on pain.)

THE ROLE OF PARENTS DURING PROCEDURES

Nonpharmacological strategies, such as distraction, are useful as pain-controlling maneuvers, because children are particularly responsive to imaginative play. Imaginative play delivered by a parent or other familiar figure to provide comforting physical contact and distraction is even more powerful.96

Parental assistance appears to be crucial for addressing the three stages of coping with procedure-associated pain: anticipation of the procedure (i.e., whether it is appraised as a harm/loss, a threat, a challenge to be overcome, or an activity that is ultimately valuable in fighting disease); the actual procedure (encounter); and the aftermath (recovery) period. The anticipation stage may be associated with apprehension and psychological distress; coping responses during this stage may be directed toward managing anxiety or fear. The encounter stage is characterized not only by psychological distress but also by physiological sensations of pain. The recovery phase may include coping with feelings of having been assaulted and may also require coping that reduces pain or regulates reactions to pain. Not surprisingly, children may cope in different ways during different stages of medical stressors. For example, children are more likely to engage in verbal coping (humor) during the nonpainful stages, and audible, deep breathing is more frequent during the painful stages.29

Data on the effect of parental presence during stressful medical procedures are mixed.97 Much depends on the parents’ tolerance for pain in their child, which is based on their understanding the reason for the procedure and the intent of the person doing the procedure. Parental support may facilitate children’s adaptive coping responses. Alternatively, certain parental behaviors, such as empathic comments, apologies to the child, criticism, undue reassurance, and affording the child control over when the procedure begins, actually increase the child’s distress.97 This variability in research findings on parental presence may also relate to parental characteristics. For example, children with anxious mothers exhibit greater anxiety in their mother’s presence, whereas children with mothers who are not anxious show more distress in their mother’s absence.29

THE COMPETENCY OF MINORS TO MAKE MEDICAL DECISIONS

Being considered competent to make a decision implies being able to understand the risks, benefits, and alternatives when choices are available and to express a choice between the alternatives; to demonstrate logical and rational reasoning; to make a “reasonable” choice; and to make a choice without coercion. Children in Piaget’s preoperational stage are unable to reason beyond their own personal experiences and are limited in their understanding of cause-and-effect relationships. During the concrete operational stage, children begin to think logically, but only about things that are physically present or that they have experienced. However, in the formal operational stage, children show an intellectual capacity to reason, generalize beyond personal experience, deal with abstract ideas, and hypothesize or predict potential consequences of actions. Apart from inexperience, most individuals 14 years of age and older have the same capacities for processing information as do adults.98 Bibace and Walsh11 found that more than 40% of 11-year-old children understood that disease has a physiological basis. Thus, children begin to understand disease processes around the age of 10 or 11 and demonstrate the competence to make treatment decisions by the age of 14.

Virtually all states recognize the concept of the emancipated minor (i.e., married or living independently without parental financial support) as a person who is able to make his or her own health care decisions. The concept of the mature minor (an individual who is capable of fully appreciating the nature and consequences of a particular treatment) is, however, not recognized in all states, although it is part of Canadian law.99 The concept of the mature minor is a higher standard than that of the emancipated minor, inasmuch as it demands specific knowledge and understanding, rather than mere circumstances, to grant decision-making rights. What, however, should be the level of participation in decision making by teenagers who are not capable of full understanding?

In adolescent decision making, the proportionality of a decision, such as the withdrawing of life-sustaining treatment, may be considered.100 Proportionality refers to a “sliding scale” of competency: The more important or serious the outcome, the higher the level of competency that should be required to make that decision. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics,… physicians and parents should give great weight to clearly expressed views of child patients regarding life-sustaining medical treatment, regardless of the legal particulars.”101 Similarly, the Society for Adolescent Medicine has stated the general principle that an adolescent should have a major decision-making role in agreeing to participate in the research process.102 Although neither the American Academy of Pediatrics nor the Society for Adolescent Medicine endorses sole decision making by the pediatric patient, the shift from “great weight” given to children’s opinions to “major” decision making by adolescents reflects the growing influence of the child’s wishes as he or she matures. Although most formal discussion of the capacity of pediatric patients to make informed decisions has centered on life-sustaining treatments and research participation, proponents of greater child patient participation in decision making have suggested that all clinical situations be opened for discussion at the policy-making level.98

Optimally, the adolescent does participate in all health care decisions, including those concerning life-sustaining medical treatment, with the health care team and parents in a supportive environment. On occasion, the adolescent disagrees with the parents, physicians, or both. Under this circumstance, all parties should receive accurate information on prognosis, treatment options, and the clinical course with and without treatment. The physician should assess an adolescent’s ability to comprehend and reflect on the choices available, to balance risks and benefits, and to understand the implications of his or her decisions. When an adolescent has the capacity to make competent health care decisions, the ethical physician should allow the adolescent the right to exercise autonomy.98

TRANSITION TO ADULT CARE

Overall, children with special health care needs born during the early 21st century have a 90% chance of surviving into adulthood. The lack of familiarity of many adult physicians with the management of chronic diseases that begin in childhood has been an issue for several decades.103 Despite endorsements of the concept of a smooth transition from pediatric to adult care by many specialty organizations, no consensus exists as to how this transition should be made, and few training programs proactively address this issue.104

Because of the complexity of many childhood conditions and their effects on families, health care for youth with special needs typically entails an interdisciplinary model that stresses family-centered care (for more detail, see Chapter 8B). Such family-centered models are rare in adult health care settings, which typically stress the autonomy of adult patients. Thus, it is not uncommon for older teenage or young adult patients with chronic illnesses (e.g., cystic fibrosis, sickle cell anemia) to be cared for by a pediatric team consisting of physicians, nurses, social workers, and child life specialists, all working in concert with the family to provide reliable, ongoing care. With transfer of care to an adult provider, the patient is expected to function autonomously. The influence of chronic illness on patient and family functioning, especially the effect of illness on young adults’ transition to independence, is rarely understood or addressed in the adult care setting.

To address this issue, some institutions have attempted to have physicians who are trained in both pediatrics and internal medicine provide care for late teenage and young adult patients with chronic conditions. However, the number of such physicians, especially those with subspecialty training in such relevant disciplines as cardiology, hematology/oncology, and pulmonology is very small. A more feasible approach is to view transition as a twofold issue: (1) the educational and technical aspects of diagnosis and treatment and (2) the socioemotional aspects of management. In this model, the former is primarily the responsibility of internists and other adult providers who must expand their training experience to include care of chronic pediatric conditions that extend into adulthood. The latter is the responsibility of pediatric providers who must improve their direct communication with teenage patients, promote self-efficacy in both patients and families, and allow for a graduated move toward autonomy and independence that mirrors the developmental tasks of every family with children.

1 Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion: Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion-First International Conference on Health Promotion, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, November 21, 1986. (Available at http://www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/ottawa_charter_hp.pdf.)

2 World Health Organization. The World Health Report: Conquering Suffering, Enriching Humanity. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1997.

3 Perrin EC, Gerrity PS. There’s a demon in your belly: Children’s understanding of illness. Pediatrics. 1981;67:841-849.

4 Chin DG, Schonfeld DJ, O’Hare LL, et al. Elementary school-age children’s developmental understanding of the causes of cancer. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1998;19:397-403.

5 Shoemaker MR, Schonfeld DJ, O’Hare LL, et al. Children’s understanding of the symptoms of AIDS. AIDS Educ Prev. 1996;8:414.

6 Berry SL, Hayford JR, Ross CK, et al. Conceptions of illness by children with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: A cognitive developmental approach. J Pediatr Psychiatry. 1993;18:83-97.

7 Chang C, Chen LH, Chen PY. Developmental stages of Chinese children’s concepts of health and illness in Taiwan. Zhonghua Min Guo Xiao Er Ke Yi Xue Hui Za Zhi. 1994;35:27-35.

8 Sanger MS, Perrin EC, Sandler HM. Development in children’s causal theories of their seizure disorders. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1993;14:88-93.

9 Peltzer K, Promtussananon S. Black South African children’s causal theories of their seizure disorders. Child Care Health Dev. 2003;29:385-393.

10 Burbach DJ, Peterson L. Children’s concepts of physical illness: A review and critique of the cognitive-developmental literature. Health Psychol. 1986;5:307-325.

11 Bibace R, Walsh ME. Development of children’s concepts of illness. Pediatrics. 1980;66:912-917.

12 Brewster AB. Chronically ill hospitalized children’s concepts of their illness. Pediatrics. 1982;69:355-362.

13 Perrin EC, Sayer AG, Willett JB. Sticks and stones may break my bones … Reasoning about illness causality and body functioning in children who have a chronic illness. Pediatrics. 1991;88:608-619.

14 Crisp J, Ungerer JA, Goodnow JJ. The impact of experience on children’s understanding of illness. J Pediatr Psychol. 1996;21:57-72.

15 Goldman SL, Whitney-Saltiel D, Granger J, et al. Children’s representations of “everyday” aspects of health and illness. J Pediatr Psychol. 1991;16:747-766.

16 Schonfeld DJ. Teaching young children about HIV and AIDS. Child Adolesc Clin North Am. 2000;9:375-387.

17 Schonfeld DJ, O’Hare LL, Perrin EC, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a school-based, multifaceted AIDS education program in the elementary grades: The impact on comprehension, knowledge and fears. Pediatrics. 1995;95:480-486.

18 Chin DG, Schonfeld DJ, O’Hare LL, et al. Elementary school-age children’s developmental understanding of the causes of cancer. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1998;19:397-403.

19 Piaget J. The Origins of Intelligence in Children. New York: International Universities Press, 1952.

20 Piaget J. The Child’s Conception of Physical Causality. London: Kegan Paul, 1930.

21 Hergenrather JR, Rabinowitz M. Age-related difference in the organization of children’s knowledge of illness. Dev Psychol. 1991;27:952-959.

22 Raman L, Gelman SA. Children’s understanding of the transmission of genetic disorders and contagious illnesses. Dev Psychol. 2005;41:171-182.

23 Krishnan B, Glazebrook C, Smyth A. Does illness experience influence the recall of medical information? Arch Dis Child. 1998;79:514-515.

24 Gardner R. The guilt reaction of parents of children with severe physical disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1969;126:636-644.

25 Olney MF, Kim A. Beyond adjustment: Integration of cognitive disability into identity. Disabil Soc. 2001;16:563-583.

26 Richardson CR. Educational interventions improve outcomes for children with asthma. J Fam Pract. 2003;52:764-766.

27 Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK, Saltzman H, et al. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychol Bull. 2001;127:87-127.

28 Eisenberg N, Fabes RA, Guthrie I. The roles of regulation and development. In: Sandler JN, Wolchik SA, editors. Handbook of Children’s Coping with Common Stressors: Linking Theory, Research, and Intervention. New York: Plenum Press; 1997:41-70.

29 Rudolph KD, Denning MD, Weisz JR. Determinants and consequences of children’s coping in the medical setting: Conceptualization, review, and critique. Psychol Bull. 1995;118:328-357.

30 Field T, Alpert B, Vega-Lahr N, et al. Hospitalization stress in children: Sensitizer and repressor coping styles. Health Psychol. 1988;7:433-445.

31 Siegel LJ. Hospitalization and medical care of children. In: Walker E, Roberts M, editors. Handbook of Clinical Child Psychology. New York: Wiley; 1983:1089-1108.

32 Worchel FF, Copeland DR, Barker DG. Control-related coping strategies in pediatric oncology patients. J Pediatr Psychol. 1987;12:25-38.

33 Crouch MD. Children with Cancer: A Study of Coping in the Medical Setting. Los Angeles: University of California, 1999. (Dissertation)

34 Spinetta JJ. The dying child’s awareness of death: A review. Psychol Bull. 1974;81:256-260.

35 Spinetta JJ. Adjustment in children with cancer. Pediatr Psychol. 1977;2:49-51.

36 Schonfeld DJ. Talking with children about death. J Pediatr Health Care. 1993;7:269-274.

37 Dolgin M, Phipps S. Reciprocal influences in family adjustment to childhood cancer. In: Baider L, Cooper C, Kaplan de-Nour A, editors. Cancer and the Family. Oxford, UK: Wiley; 1996:73-92.

38 Kazak AE, Alderfer M, Rourke MT, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) in families of adolescent childhood cancer survivors. J Pediatr Psychol. 2004;29:211-219.

39 Sahler OJ, Roghmann KJ, Mulhern RK, et al. Sibling adaptation to childhood cancer collaborative study: The association of sibling adaptation with maternal well-being, physical health, and resource use. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1997;18:233-243.

40 Barrera M, D’Agostino NM, Gibson J, et al. Predictors and mediators of psychological adjustment in mothers of children newly diagnosed with cancer. Psychooncology. 2004;13:630-641.

41 Landolt MA, Vollrath M, Ribi K, et al. Incidence and associations of parental and child posttraumatic stress symptoms in pediatric patients. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2003;44:1199-1207.

42 Lansky SB, Cairns NU. The Family of the Child with Cancer. New York: American Cancer Society, 1979.

43 Overholser JC, Fritz GK. The impact of childhood cancer on the family. J Psychosoc Oncol. 1990;8:71-85.

44 Sloper P. Predictors of distress in parents of children with cancer: A prospective study. J Pediatr Psychol. 2000;25:79-91.

45 Steele RG, Dreyer ML, Phipps S. Patterns of maternal distress among children with cancer and their association with child emotional and somatic distress. J Pediatr Psychol. 2004;29:507-517.

46 Noll RB, Gartstein MA, Hawkins A, et al. Comparing parental distress for families with children who have cancer and matched comparison families without children with cancer. Fam Syst Med. 1995;13:11-28.

47 Frank NC, Brown RT, Blount RL, et al. Predictors of affective responses of mothers and fathers of children with cancer. Psychooncology. 2001;10:293-304.

48 Hoekstra-Weebers JEHM, Jaspers JPC, Kamps WA, et al. Psychologic adaptation and social support of parents of pediatric cancer patients: A prospective longitudinal study. J Pediatr Psychol. 2001;26:225-235.

49 Steele RG, Long A, Reddy KA, et al. Changes in maternal distress and child-rearing strategies across treatment for pediatric cancer. J Ped iatr Psychol. 2003;28:447-452.

50 Kupst MJ, Schulman JL. Long-term coping with pediatric leukemia: A six-year follow-up study. J Pediatr Psychol. 1988;13:7-22.

51 Sawyer M, Antoniou G, Toogood I, et al. Childhood cancer: A 4-year prospective study of the psychological adjustment of children and parents. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2000;22:214-220.

52 Manne S, Miller D, Meyers P, et al. Depressive symptoms among parents of newly diagnosed children with cancer: A 6-month follow-up study. Child Health Care. 1996;25:191-209.

53 Brown RT, Madan-Swain A, Lambert R. Posttraumatic stress symptoms in adolescent survivors of childhood cancer and their mothers. J Trauma Stress. 2003;16:309-318.

54 Hall M, Baum A. Intrusive thoughts as determinants of distress in parents of children with cancer. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1995;25:1215-1230.

55 Kazak AE, Boeving CA, Alderfer MA, et al. Posttraumatic stress symptoms during treatment in parents of children with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7405-7410.

56 Nelson AE, Miles MS, Reed SB, et al. Depressive symptomatology in parents of children with chronic oncologic or hematologic disease. J Psychosoc Oncol. 1994;12:61-75.

57 Pelcovitz D, Goldenberg B, Kaplan S, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in mothers of pediatric cancer survivors. Psychosomatics. 1996;37:116-126.

58 Stuber ML, Christakis DA, Houskamp B, et al. Post-trauma symptoms in childhood leukemia survivors and their parents. Psychosomatics. 1996;37:254-261.

59 Stuber ML, Gonzales S, Meeske K, et al. Posttraumatic stress after childhood cancer II: A family model. Psychooncology. 1994;3:313-319.

60 Wallander JL, Varni JW. Effects of pediatric chronic physical disorders on child and family adjustment. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1998;39:29-46.

61 Dolgin MJ, Phipps S, Fairclough DL, et al: Trajectories of adjustments in mothers of children with newly diagnosed cancer: A natural history investigation. J Pediatr Psychol (in press).

62 Dahlquist LM, Czyzewski DI, Jones CL. Parents of children with cancer: A longitudinal study. J Pediatr Psychol. 1996;21:541-554.

63 Manne S, DuHamel K, Redd WH. Association of psychological vulnerability factors to posttraumatic stress symptomatology in mothers of pediatric cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2000;9:372-384.

64 Kazak AE, Alderfer MA, Streisand R, et al. Treatment of posttraumatic stress symptoms in adolescent survivors of childhood cancer and their families: A randomized clinical trial. J Fam Psychol. 2004;18:493-504.

65 Sahler OJ, Fairclough DL, Phipps S, et al. Using problem-solving skills training to reduce negative affectivity in mothers of children with newly diagnosed cancer: Report of a multisite randomized trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:272-283.

66 Fordyce WE. Pain and suffering: A reappraisal. Am Psychol. 1988;43:276-283.

67 Thompson KL, Varni JW. A developmental cognitive-biobehavioral approach to pediatric pain assessment. Pain. 1986;25:283-296.

68 Anand KJS. Clinical importance of pain and stress in preterm neonates. Biol Neonate. 1998;73:1-9.

69 Johnston CC, Stevens BJ, Yang F, et al. Differential response to pain by very premature neonates. Pain. 1995;61:471-479.

70 Barr RG, Boyce WT, Zeltzer LK. The stress-illness association in children: A perspective from the biobe-havioral interface. In: Haggerty RJ, Sherrod LR, Garmezy N, et al, editors. Stress, Risk, and Resilience in Children and Adolescents: Processes, Mechanisms, and Interventions. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1994:182-224.

71 Anand KJ, Scalzo FM. Can adverse neonatal experiences alter brain development and subsequent behavior? Biol Neonate. 2000;77:69-82.

72 Young KD. Pediatric procedural pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45:160-171.

73 Bauman BH, McManus JGJr. Pediatric pain management in the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2005;23:393-414.

74 Greco C, Berde C. Pain management for the hospitalized pediatric patient. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005;52:995-1027.

75 Hain RD, Miser A, Devins M, et al. Strong opioids in pediatric palliative medicine. Paediatr Drugs. 2005;7:1-9.

76 Chitkara DK, Rawat DJ, Talley NJ. The epidemiology of childhood recurrent abdominal pain in Western countries: A systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1868-1875.

77 Mercadante S. Cancer pain management in children. Palliat Med. 2004;18:654-662.

78 Kuttner L. Management of young children’s acute pain and anxiety during invasive medical procedures. Pediatrician. 1989;16:39-44.

79 http://www.centerwatch.com/patientdrugs/dru246.html [database online]. 2004.

80 Salmon K, Price M, Pereira JK. Factors associated with young children’s long-term recall of an invasive medical procedure: A preliminary investigation. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2002;23:347-352.

81 McGrath P. Psychological aspects of pain perception. In: Schecter N, Berde C, Yaster M, editors. Pain in Infants, Children and Adolescents. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1993:39-63.

82 Ross DM, Ross SA. Childhood pain: The school-aged child’s viewpoint. Pain. 1984;20:179-191.

83 Savedra M, Tesler M, Ward J, et al. Descriptions of the pain experience: A study of school-age children. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 1981;5:373-380.

84 Gaffney A. Cognitive developmental aspects of pain in school-age children. In: Schecter N, Berde C, Yaster M, editors. Pain in Infants, Children and Adolescents. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1993:75-83.

85 Weisz JR, McCabe M, Denning MD. Primary and secondary control among children undergoing medical procedures: Adjustment as a function of coping style. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:324-332.

86 Smith KE, Ackerson JP, Blotchy AD, et al. Preferred coping styles of pediatric cancer patients during invasive medical procedures. J Psychosoc Oncol. 1991;8:59-70.

87 Siegel L, Smith KE. Children’s strategies for coping with pain. Pediatrician. 1989;16:110-118.

88 Lumley MA, Melamed BG, Abeles LA. Predicting children’s presurgical anxiety and subsequent behavior change. J Pediatr Psychol. 1993;18:481-497.

89 Thomas A, Chess S. Temperament and Development. New York: Brunner/Mazel, 1977.

90 Boyce WT, Barr RG, Zeltzer LK. Temperament and the psychobiology of childhood stress. Pediatrics. 1992;90:483-486.

91 Evans D, Turnham L, Barbour K, et al. Intravenous ketamine sedation for painful oncology procedures. Paediatr Anaesth. 2005;15:131-138.

92 Krauss B, Green SM. Procedural sedation and analgesia in children. Lancet. 2006;367:766-780.

93 Kuppenheimer WG, Brown RT. Painful procedures in pediatric cancer: A comparison of interventions. Clin Psychol Rev. 2002;22:753-786.

94 Kazak AE, Penati B, Brophy P, et al. Pharmacologic and psychological interventions for procedural pain. Pediatrics. 1998;102:59-66.

95 Powers SW. Empirically supported treatments in pediatric psychology: Procedure-related pain. J Pediatr Psychol. 1999;24:131-145.

96 Gerik SM. Pain management in children: Developmental considerations and mind-body therapies. South Med J. 2005;98:295-302.

97 Blount R, Davis N, Powers S, et al. The influence of environmental factors and coping style on children’s coping and distress. Clin Psychol Rev. 1991;11:93-116.

98 Doig C, Burgess E. Withholding life-sustaining treatment: Are adolescents competent to make these decisions? CMAJ. 2000;162:1585-1588.

99 Rozovsky LE. Children, Adolescents, and Consent. The Canadian Law of Consent to Treatment. Toronto: Butterworths, 1997;61-75.

100 Gaylin W. The competence of children: No longer all or none. Hastings Cent Rep. 1982;12:33-38.

101 American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Bioethics. Guidelines on foregoing life-sustaining medical treatment. Pediatrics. 1994;93:532-536.

102 Sigman G, Silber TJ, English A, et al. Confidential health care for adolescents: Position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J Adolesc Health. 1997;21:408-415.

103 Schidlow DV. Transition in cystic fibrosis: Much ado about nothing? A pediatrician’s view. Pediatr Pulm-onol. 2002;33:325-326.

104 Hagood JS, Lenker CV, Thrasher S. A course on the transition to adult care of patients with childhood-onset chronic illness. Acad Med. 2005;80:352-355.