Acute surgical problems in children

Introduction

A neonate is a newborn less than 28 days old, an infant is less than a year, a child is 1–18 years old and an adult is 18 or older. In the UK, those between 13 and 18 are increasingly being managed in adolescent units, where their needs are better met. Many children are treated by general surgeons with a paediatric interest, but surgical problems in infants, major congenital abnormalities and malignant tumours are usually managed in regional centres by specialists. The range of surgical conditions in children differs from adults and varies between age groups, particularly for emergency presentations. Paediatric emergencies are considered here by age group, i.e. newborn (the first few days of life, including premature babies), infants and young children (up to about 2 years) and older children (up to puberty). During puberty, the disorders merge with those of adulthood. Non-emergency and urogenital disorders are less age-specific (see Ch. 51).

Physiological differences between infants and adults

Abdominal emergencies in the newborn

The more common neonatal abdominal emergencies are summarised in Box 50.1. All are congenital with the exception of necrotising enterocolitis.

Intestinal obstruction

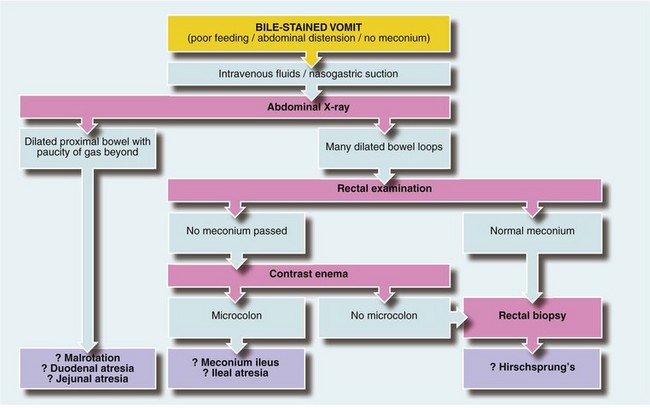

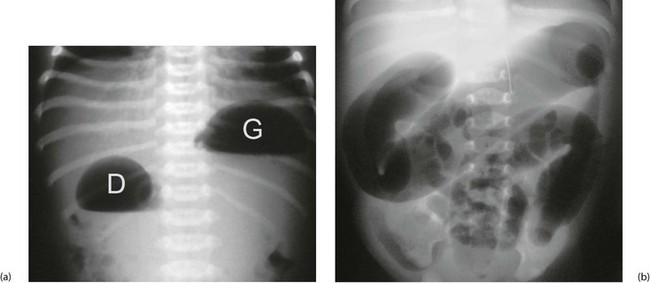

The important causes of upper intestinal obstruction in babies are duodenal atresia and malrotation with volvulus. Causes of low obstruction include Hirschsprung’s disease and meconium ileus. Small bowel atresia may affect jejunum or ileum, causing high or low obstruction respectively. Plain abdominal X-rays usually confirm intestinal obstruction. When obstruction is high, there is a lack of distal intestinal gas (Fig. 50.1a); when low, there are dilated loops of bowel (Fig. 50.1b). If malrotation is suspected, an upper GI contrast study can determine the abnormal position of the duodeno-jejunal flexure. Other causes such as incarcerated inguinal hernia or imperforate anus can be detected by clinical examination. A plan for managing babies with suspected obstruction is outlined in Fig 50.2.

Fig. 50.1 Intestinal obstruction

(a) Erect plain abdominal X-ray of a baby with ‘high’ intestinal obstruction, showing the typical ‘double bubble’ appearance of gas in the dilated stomach G and the first part of the duodenum D. The differential diagnosis includes duodenal atresia, malrotation with volvulus obstructing the duodenum and a very high jejunal atresia. Fluid levels are seen in this erect film.

(b) Abdominal X-ray of a baby with a ‘low’ intestinal obstruction, showing several dilated loops of bowel. The differential diagnosis includes Hirschsprung’s disease, meconium ileus and ileal atresia

Gastrointestinal atresias and stenoses

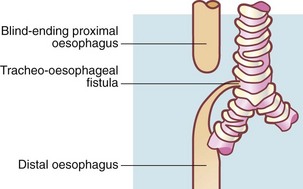

Oesophageal abnormalities: Potentially lethal oesophageal abnormalities occur in 1 in 3000 live births and there is associated polyhydramnios in nearly 30%. Oesophageal atresia with a distal tracheo-oesophageal fistula (TOF, Fig. 50.3) accounts for 90% of these, pure oesophageal atresia without a fistula for 5% and other variations for the other 5%. Babies with oesophageal atresia may have other abnormalities as part of a spectrum of disorders, the VACTERL association. This may include one or more V—vertebral, A—anorectal, C—cardiac, T—TOF, E—‘(o)esophageal’ atresia, R—renal and L—limb abnormalities.

Fig. 50.3 Oesophageal atresia with tracheo-oesophageal fistula

This is the most common variant of oesophageal atresia, found in 90% of cases. Air enters the gastrointestinal tract via the fistula and may be seen on plain X-ray. ‘Frothy’ breathing may occur because the mouth and pharynx are full of saliva

Duodenal obstruction: Duodenal atresia causes obstruction of the second part of the duodenum, usually just below the common bile duct entry resulting in bile-stained vomiting. The anomaly is a web across the lumen or complete separation of the bowel ends. If the web is incomplete, there is initial poor feeding and failure to thrive until a milk curd impacts, causing obstruction. Plain abdominal X-ray shows a double bubble, with one air–fluid interface in the stomach and another in the duodenum (Fig. 50.1a).

Jejuno-ileal atresias: Jejunal or ileal atresias are similar to duodenal atresia, with a gap between bowel ends or an intraluminal web. A gap is often the result of a mesenteric vascular accident in utero. Obstructions occur at any level and are sometimes multiple. Bile-stained vomiting and abdominal distension are often associated with visible peristalsis and hypertrophied proximal bowel. The diagnosis is usually evident from the abdominal X-ray.

Obstruction may be present from birth or delayed a few days if a web is incomplete. Presenting signs depend on the level of obstruction: high jejunal obstruction presents like duodenal atresia or malrotation with bile-stained vomiting and a lack of gas on X-ray (Fig. 50.1a); low ileal obstruction presents like meconium ileus or Hirschsprung’s disease, with failure to pass meconium, poor feeding, abdominal distension and dilated intestine on X-ray. Small bowel atresia is sometimes associated with cystic fibrosis, and patients should have a genetic screen and a sweat test to exclude it.

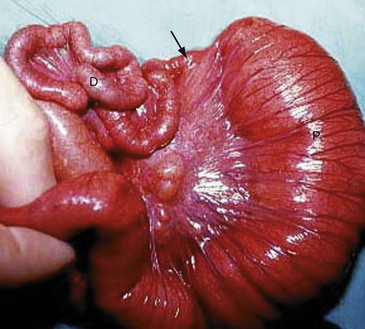

Surgery involves resecting the web segment or the blind ends and end-to-end anastomosis. Return of intestinal function may be slow, but may be accelerated if the most dilated and atonic proximal bowel is resected too (Fig. 50.4).

Fig. 50.4 Jejunal atresia

Findings at laparotomy on a neonate presenting with intestinal obstruction. The proximal jejunum P is greatly dilated whilst the distal jejunum is collapsed D. In between is an atretic segment without a lumen (arrow). This was resected and the bowel ends joined. The infant thrived soon afterwards

Midgut malrotation with volvulus

Pathophysiology: The midgut develops outside the abdomen during early embryological development. By the end of the third month, it normally returns, rotating 270° anti-clockwise, giving a normally sited duodeno-jejunal (DJ) flexure and the caecum in the right iliac fossa. The midgut mesentery is wide, stretching obliquely across the posterior abdominal wall, preventing volvulus. If rotation is incomplete, the DJ flexure lies right of the midline rather than left; the mesenteric fixation to the posterior abdominal wall is narrow and volvulus may occur. At one time Ladd’s bands (peritoneal folds across the duodenum) were thought responsible but it is now known that volvulus is the usual cause.

Acute volvulus: Children with malrotation may undergo acute volvulus at any time, in which the mass of bowel twists on its axis, occluding the superior mesenteric (midgut) vessels, causing intestinal ischaemia and infarction. This is a surgical emergency presenting as high intestinal obstruction with bile-stained vomiting. Plain radiographs show features similar to any other high obstruction (Fig. 50.1a). Previously well children who present acutely with sudden duodenal obstruction, particularly with signs of peritonitis, should have very urgent surgery to prevent midgut infarction. At operation, the bowel is untwisted and any gangrenous bowel resected. Surgery also involves dividing Ladd’s bands. This broadens the mesenteric base by moving the duodenum to the right and caecum to the left. A stable situation is thus created, reducing the risk of recurrent volvulus. If there is insufficient small bowel remaining, short bowel syndrome (intestinal insufficiency) is likely.

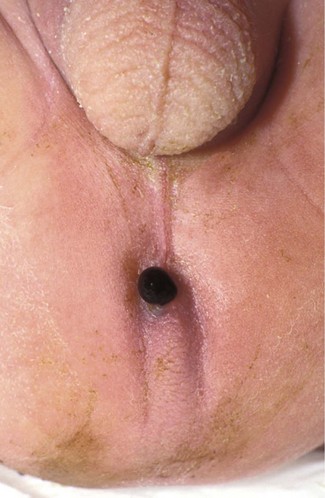

Anorectal abnormalities

There is a spectrum of congenital anorectal disorders (imperforate anus) that has led to complex classifications. However, clinically, it is sufficient to separate imperforate anus into high or low according to whether the bowel terminates above or below levator ani. In nearly all, there is a fistula from the end of the bowel. When the malformation is low, the fistula opens to skin anterior to the sphincter complex and meconium may emerge from it; because of this, the abnormality may not be immediately recognised (Fig. 50.5). Newborn babies need to be carefully examined to ensure the anus is situated correctly. In high malformations, there is usually a fistula to the urethra in the male or vagina in the female. Patients with a urethral fistula require prophylactic antibiotics to prevent UTIs. Urinary tract malformations and lower vertebral anomalies are commonly associated with anorectal abnormalities and should be sought.

Failure to pass meconium

In meconium ileus, the distal ileum is obstructed by abnormal thick, viscid meconium and mucus plugs. About 95% of babies with this have cystic fibrosis and all babies with meconium ileus must be tested for it. The colon and rectum distal to the obstruction are of very small calibre. This microcolon results from the fact that no bowel contents have passed down it rather than any inherent abnormality (Fig. 50.6).

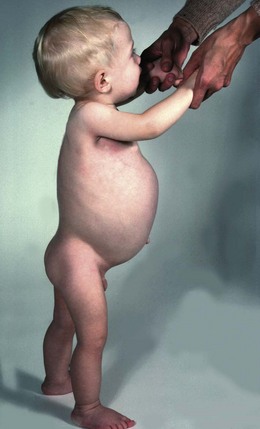

Hirschsprung’s disease (congenital aganglionosis)

Peristalsis is deficient in the affected bowel and the internal anal sphincter does not relax. The baby therefore has a functional obstruction that usually presents soon after birth with intestinal obstruction; in patients with long-segment disease, it can present in later childhood with constipation and failure to thrive (Fig. 50.7). About 80% of normal babies pass meconium within the first 24 hours but about 80% of babies with Hirschsprung’s disease do not, and this is a diagnostic pointer.

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia

Failure of the pleuroperitoneal canal to close results in the most common type of diaphragmatic hernia (Fig. 50.8b) which is postero-lateral. The incidence is 1 : 3500 live births and 80% are on the left side. Abdominal viscera lie in the chest, displacing the mediastinum. Lung development is abnormal, with fewer branching events during development causing variable pulmonary hypoplasia (Fig. 50.8a), which may be so severe as to be incompatible with life.

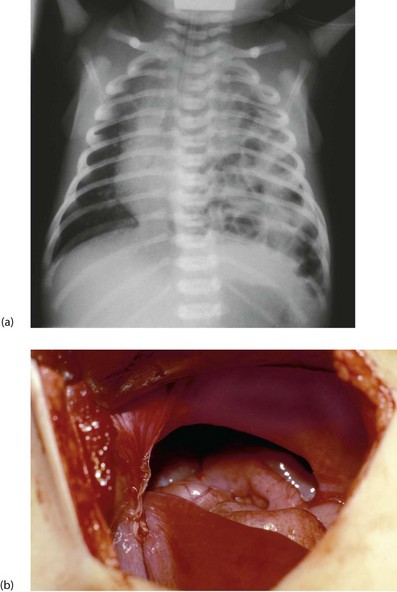

Fig. 50.8 Congenital diaphragmatic hernia

(a) Plain chest X-ray showing air-containing loops of bowel in the left chest and displacement of the mediastinum to the right. Note the endotracheal tube in place to allow assisted ventilation. (b) An operative picture viewed from the abdomen, showing the pleuro-peritoneal canal defect in the diaphragm. Some of the intestine had already been reduced from the thorax

Other surgical conditions causing respiratory problems in the newborn

Abdominal wall defects

Major deficiencies in the anterior abdominal wall are dramatically obvious antenatally on ultrasound and at birth. They originate from a midline abdominal wall defect so much of the bowel (and sometimes other viscera) lies outside the abdominal cavity, with or without a membranous covering. In exomphalos (or omphalocoele), the viscera are invested with a layer of amnion whereas in gastroschisis (Fig. 50.9) coils of bare gut are exposed. Ectopia vesicae (bladder exstrophy) is the rarest of the major defects and is more common in boys. It presents as a defect between the rectus muscles and pubic bones with failed development of the entire anterior wall and neck of the bladder and urethra.

Gastroschisis

This abdominal wall defect is characterised by bowel herniation through a slit-like defect right of the umbilicus. There are few associated congenital problems, although babies may be small and are often premature. The defect is usually about 3 cm long and the bowel has no covering membrane (Fig. 50.9). A narrow defect may impair the intestinal blood supply in the fetus causing small bowel atresias. Malrotation or non-rotation is usually present. Antenatal exposure to amniotic fluid can cause adhesions and shortened oedematous bowel loops which may lead to intestinal insufficiency.

Treatment of exomphalos major and gastroschisis: The aim is to reduce the viscera and close the abdominal wall. In gastroschisis, primary abdominal wall closure is often possible. In exomphalos, part of the abdominal wall is missing and the abdominal cavity never reached its normal capacity so primary closure would cause diaphragmatic splinting and IVC compression. In these, a silo bag covering the intestine can be placed and the bowel progressively reduced by putting tucks into the silo, expanding the intra-abdominal volume. Repair is performed when this is complete. Intravenous feeding is usually needed until normal bowel activity returns. The mortality rate for even large lesions requiring a silo is low except when associated with cardiac malformations.

Abdominal emergencies in infants and young children

Pathophysiology

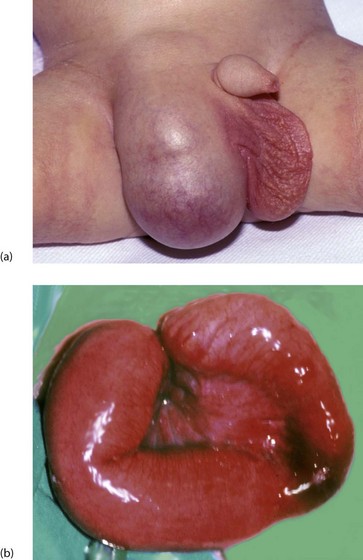

The description incarcerated means a hernia has become acutely irreducible, whereas the term strangulated implies there is also impairment of the blood supply to its contents. Strangulation can follow incarceration but luckily is uncommon in young children, unlike in adults (Fig. 50.10).

Clinical features

When a hernia incarcerates it becomes painful, tender and irreducible. Classically, a mother discovers a firm lump in the groin in her crying (usually male) child. He may have vomited but the diagnosis is usually made before intestinal obstruction becomes established. The child is usually well with an obvious, irreducible lump in the groin (Fig. 50.10) sometimes extending into the scrotum. If bowel becomes obstructed, vomiting follows, causing fluid depletion and electrolyte disturbances. The blood supply of the incarcerated segment of intestine may become obstructed (strangulation) causing bowel infarction (Fig. 50.10b). Pressure on the spermatic cord at the external ring may cause testicular vascular obstruction, and rapid treatment is needed to prevent testicular infarction and irreversible damage.

Congenital hypertrophic pyloric stenosis

Treatment

The natural history without surgery is for the hypertrophy to gradually resolve over several months. However, most children would die from electrolyte disturbances or malnutrition before this happened. Treatment is surgical, by Ramstedt’s pyloromyotomy—Figure 50.11—described in 1912 (Conrad Ramstedt, 1867–1963). However GA in an unprepared neonate with alkalosis and an immature respiratory drive would often result in prolonged postoperative ventilation and all its attendant risks. Operation should be performed only on a stable baby after correcting dehydration responsible for the metabolic alkalosis. The stomach should be emptied by nasogastric aspiration and washed out with normal saline to prevent further vomiting.

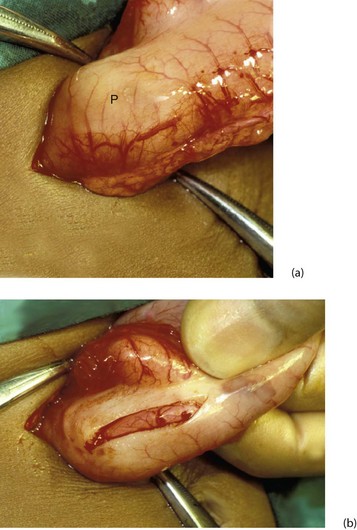

Fig. 50.11 Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis—Rammstedt’s operation

(a) A small supra-umbilical incision has been made and the stomach and pyloric ‘tumour’ P delivered. (b) The serosa over the tumour has been incised and the hypertrophic muscle split with forceps. The mucosa is seen bulging through the muscle split

In the classical operation, operation is via an incision lateral to the umbilicus. Nowadays the procedure is carried out via a periumbilical incision or laparoscopically. The hypertrophied pyloric muscle is incised longitudinally and then split without breaching the mucosa (Fig. 50.11). Postoperative recovery is rapid, with full-strength milk feeding started immediately afterwards. Babies typically tolerate sufficient feeds to be discharged within 24 h. Babies with a prolonged preoperative course may develop gastritis, which may itself lead to postoperative vomiting; this may be helped by ranitidine.

Intussusception

Intussusception is an acquired disorder most common between the ages of 6 weeks and 2 years. There appears to be a seasonal increase in the spring and autumn. Up to 40% of children with intussusception have adenovirus infection, commoner at these times of year. Intussusception arises when a proximal segment of bowel becomes telescoped or prolapsed into the bowel immediately distal to it (Fig. 50.12). The lead point (intussusceptum) is commonly a thickening of bowel wall caused by non-specific or viral hypertrophy of Peyer’s lymphatic patches. The invaginated segment progressively elongates as it is propelled distally by peristalsis. Ileocolic intussusception is the usual variety and it commonly extends well into the transverse colon and sometimes even prolapses from the anus.

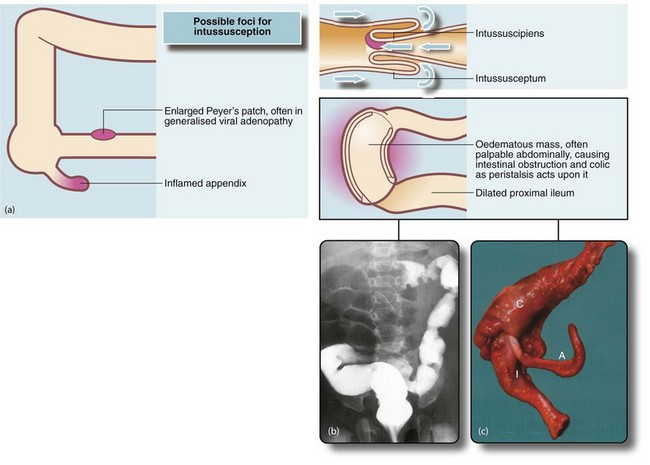

Fig. 50.12 Intussusception

(a) Mechanism of intussusception. (b) This 2-year-old child presented as an emergency with spasms of abdominal pain, having passed ‘redcurrant jelly’ rectally. This barium enema shows the typical appearance of large bowel obstruction by an intussusception of ileum which in this case has progressed to the transverse colon. The barium infusion pressure was increased, resulting in hydraulic reduction of the intussusception which did not recur. (c) In this case neither preoperative barium enema nor manual attempts at reduction were successful so the terminal ileum I and ascending colon C were resected. Note the appendix A

Management

Treatment needs to be prompt and active. Intravenous access should be secured early as deterioration may be imminent. Fluid resuscitation is vital even before attempting to diagnose or reduce an intussusception in an often isolated radiology department. Patients are usually given a fluid bolus of 20ml/kg of suitable crystalloid and an empirical broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy before transfer to the radiology department. The intussusception can usually be reduced using an air enema with carefully controlled pressure, performed under X-ray screening (Fig. 50.12b). Reported rates of successful reduction are as high as 90%. Radiological reduction is inappropriate if the child is unwell; in these, rapid resuscitation should be followed by laparotomy. At operation, the intussusception is reduced by gentle manipulation. Resection with primary bowel anastomosis becomes necessary if the intestine is ischaemic or if it proves impossible to completely reduce without causing major trauma to the bowel (see Fig. 50.12c).

Swallowed foreign body

Young children examine their environment with their mouths and frequently swallow foreign bodies such as coins, safety pins, buttons or plastic objects. A potentially dangerous foreign body is a mercury button battery (Fig. 50.13). The greatest danger is that electrical currents allow it to burn through the stomach wall. There is also a danger of disintegration, releasing toxic mercury salts. Button batteries remaining in the stomach are removed by upper GI endoscopy or sometimes using a magnet on the end of a nasogastric tube. After passing beyond the stomach, GI propulsive agents and laxatives are given and the child is admitted until the battery passes out.

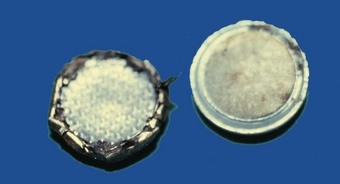

Fig. 50.13 Ingested foreign bodies

Mercury battery. Young children often put small hearing aid-type batteries into their mouths. They are at risk from inhalation and bronchial obstruction, and also from electrical activity burning through the stomach wall. Batteries can be removed without anaesthesia or sedation using a magnet on the end of a nasogastric tube

Abdominal emergencies in older children

Differential diagnosis (Box 50.2)

From childhood to adolescence, acute abdominal pain is a common cause of surgical admission. Appendicitis is usually suspected (see Ch. 26). Major differential diagnoses are acute non-specific abdominal pain (common), closely followed by mesenteric adenitis (Box 50.2). Mesenteric adenitis sometimes causes a higher fever than appendicitis and signs and symptoms usually settle within 24 hours; there is often a recent history of viral upper respiratory tract infection, and enlarged cervical lymph nodes may be palpable.

Less commonly, acute abdominal pain in this age group is caused by extra-abdominal causes such as:

Torsion of the testis

Torsion can occur when there is a congenital abnormality of testicular fixation (termed the ‘bell-clapper’ testis) that predisposes to twisting on its vascular pedicle. The diagnosis must be considered in any male less than 25 years of age presenting with acute testicular pain. Torsion may present with iliac fossa pain alone, without testicular pain. Torsion must not be missed as the testis undergoes necrosis within 4–6 hours. Predisposition to torsion is usually bilateral and both testes are at risk; thus the non-torted testis should undergo fixation at the same time as the torted testis (see Ch. 33).

When a diagnosis of torsion cannot be excluded, the only safe option is to carry out urgent surgical exploration. If torsion is present and the testis is viable, it should be untwisted and fixed to prevent re-torsion. A non-viable testis should be removed and the contralateral testis should be fixed at the same time since predisposition to torsion is usually bilateral and both testes are at risk (see Ch. 33).