49 Acute Rheumatic Fever and Rheumatic Heart Disease

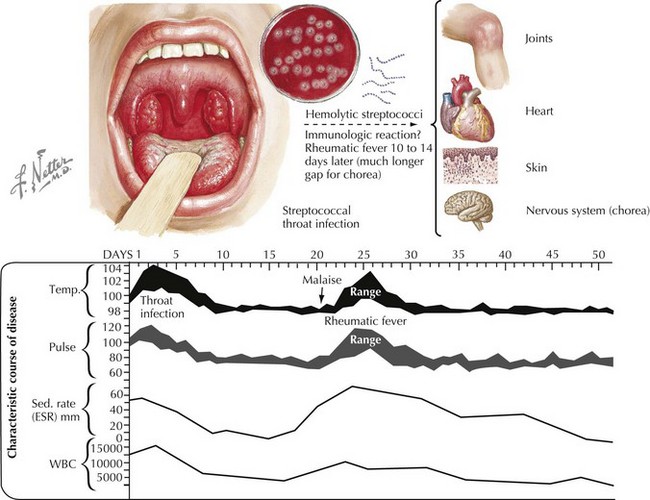

Acute rheumatic fever (ARF) is postulated to be caused by a delayed systemic autoimmune reaction to group A β-hemolytic streptococcal (GAS) pharyngitis. It is a self-limited disease that may involve the heart, skin, brain, joints, and serosal surfaces (Figure 49-1). It is a disease of clinical interest primarily because of its propensity to create heart disease. Rheumatic carditis and valvulitis may be self-limited or may lead to progressive valve deformity.

Etiology And Pathogenesis

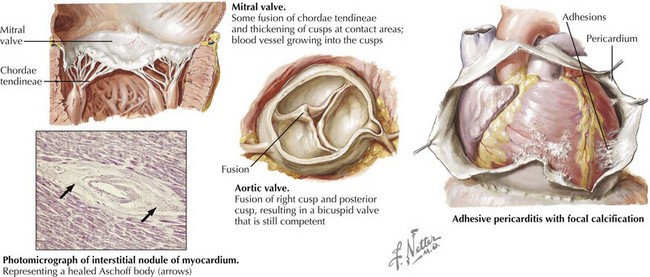

The virulence of GAS is related to the bacterial M protein, which structurally resembles human myosin. It is presumed that GAS adheres to the pharyngeal mucosa of the patient and activates antigens and superantigens, which triggers an immune response. In genetically susceptible individuals, antibodies against myosin are produced, which can lead to carditis. Repeated untreated infections with GAS may reactivate antibody production and lead to an autoimmune response that lasts several weeks and eventually damages heart valves (Figure 49-2).

Clinical Presentation

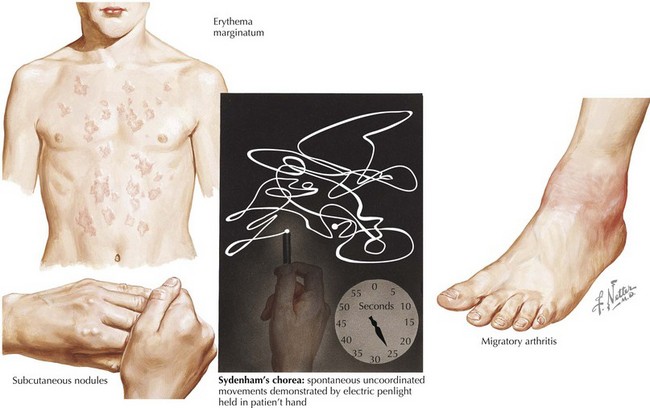

More than 60 years ago, T. Duckett Jones published guidelines for diagnosis of ARF that have been slightly revised by the World Health Organization (Box 49-1 and Figure 49-3). To make a primary diagnosis of ARF, two major or one major and two minor criteria plus evidence of a preceding GAS infection are needed. The exception is rheumatic chorea. Sydenham’s chorea (St. Vitus dance) in isolation is considered diagnostic, and no other criteria or evidence of GAS infection are required to make the diagnosis.

Box 49-1 2002 to 2003 World Health Organization Revision of Jones Criteria for the Diagnosis of Rheumatic Fever

Major Criteria

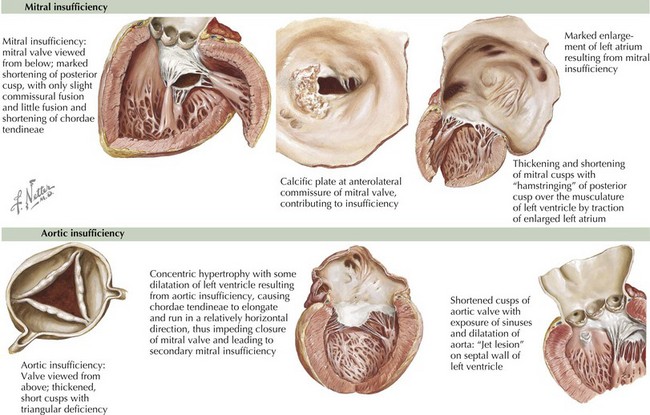

A history of ARF is obtained in only 60% of patients with RHD. Whereas chronic mitral regurgitation is the most common form of RHD in children and young adults (Figure 49-4), mitral stenosis is more common in older adults. Aortic regurgitation, although less common than mitral regurgitation with ARF, is more likely to persist (see Figure 49-4). Patients with mitral or aortic valve disease may present with an isolated heart murmur or palpitations caused by atrial arrhythmias. They can present with fatigue, decreased exercise tolerance, dyspnea on exertion, orthopnea, and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, which can represent low cardiac output or pulmonary hypertension. However, the onset of symptoms can often be so insidious that patients adapt and are unaware of their significant functional limitations.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Cardiac Evaluation

Management And Therapy

Acute Rheumatic Fever and Rheumatic Carditis

All patients with ARF should be treated with antibiotics to eliminate GAS from the throat even with negative culture results. Oral penicillin V is the drug of choice. Alternatives include single-dose benzathine penicillin injection or a course of oral ampicillin or amoxicillin. Macrolides or first-generation cephalosporins can be used in patients who are allergic to penicillin. It should be noted that some patients who are allergic to penicillin may also be allergic to cephalosporins. Because the risk of valvar heart disease is greatly increased with each subsequent attack of ARF, all patients should be placed on an antibiotic regimen for secondary prophylaxis to prevent future recurrences (Table 49-1).

Table 49-1 Antibacterial Therapy for Group A Streptococcus Pharyngitis and Acute Rheumatic Fever

| Penicillin V | Weight ≤27 kg: 250 mg PO BID or TID for 10 days Weight >27 kg: 500 mg PO BID or TID daily for 10 days |

| or | |

| Amoxicillin | 50 mg/kg PO SID (maximum, 1 g) for 10 days |

| or | |

| Benzathine penicillin G | Weight ≤27 kg: 0.6 million U IM once Weight >27 kg:1.2 million U IM once |

| Patients Allergic to Penicillin | |

| Narrow-spectrum cephalosporins: cephalexin, cephadroxil | Dose varies with selection for 10 days |

| or | |

| Clindamycin | 20 mg/kg/d PO in three doses (maximum, 1.8 g/d) for 10 days |

| or | |

| Azithromycin | 12 mg/kg PO SID (maximum, 500 mg) for 5 days |

| or | |

| Clarithromycin | 15 mg/kg/day in two doses (maximum, 250 mg BID) for 10 days |

| Secondary Prophylaxis After ARF or in Patients with Chronic RHD | |

| Benzathine penicillin G | Weight ≤27 kg: 0.6 million U IM every 3 to 4 weeks Weight >27 kg: 1.2 million U IM every 3 to 4 weeks |

| or | |

| Penicillin V | 250 mg PO BID |

| Patients Allergic to Penicillin | |

| Sulfadiazine or sulfisoxazole | Weight ≤27 kg: 0.5 g PO SID Weight >27 kg: 1 g PO SID |

| or | |

| Macrolide or azalide | Variable |

| Duration of Secondary Prophylaxis | |

| Rheumatic fever with carditis and residual heart disease | 10 years or until 40 years of age (whichever is longer), sometimes lifelong |

| Rheumatic fever with carditis but no residual heart disease | 10 years or until 21 years of age (whichever is longer) |

| Rheumatic fever without carditis | 5 years or until 21 years of age (whichever is longer) |

ARF, acute rheumatic fever; BID, twice a day; IM, intramuscular; PO, orally; RHD, rheumatic heart disease; SID, once a day; TID, three times a day.

Chronic Rheumatic Heart Disease

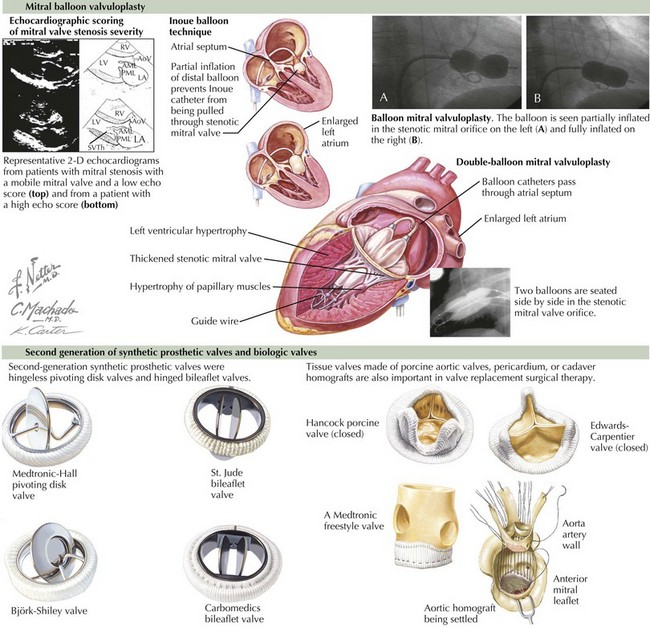

The AHA also has recommendations regarding the timing of surgical intervention for valvar heart disease based on symptoms and diagnostic testing. Percutaneous balloon valvuloplasty is the procedure of choice for patients with mitral stenosis when possible (Figure 49-5). For patients requiring surgical correction, every effort should be made to repair the native valve when feasible. However, a large number of patients go on to require surgical replacement of the valve with a pericardial, bioprosthetic, or a mechanical valve (see Figure 49-5).

Chin TK, Li D. Rheumatic fever. Emedicine. 2008.

Fyler DC. Rheumatic fever. In: Keane JF, Lock JE, Fyler DC, editors. Nadas’ Pediatric Cardiology. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2006:387-400.

Gerber MA, Baltimore RS, Eaton CB, et al. Prevention of rheumatic fever and diagnosis and treatment of acute Streptococcal pharyngitis: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, the Interdisciplinary Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology, and the Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research: endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Circulation. 2009;119(11):1541-1551.

Jones TD. The diagnosis of rheumatic fever. JAMA. 1944;126:481.

Tani LY. Rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. In: Allen HD, Driscoll DJ, Shaddy RE, Feltes TF, editors. Moss and Adams’ Heart Disease in Infants, Children, and Adolescents Including the Fetus and Young Adult. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:1256-1280.

World Health Organization. Rheumatic Fever and Rheumatic Heart Disease: Report of WHO Expert consultation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. p 923