Chapter 40 Acute renal failure

Acute renal failure (ARF) remains a major diagnostic and therapeutic challenge for the critical care physician. The term ‘ ARF’ describes a syndrome characterised by a rapid (hours to days) decrease in the kidney’s ability to eliminate waste products. Such loss of function is clinically manifested by the accumulation of end-products of nitrogen metabolism such as urea and creatinine. Other typical clinical manifestations include decreased urine output (not always present), accumulation of non-volatile acids and an increased potassium and phosphate concentration.

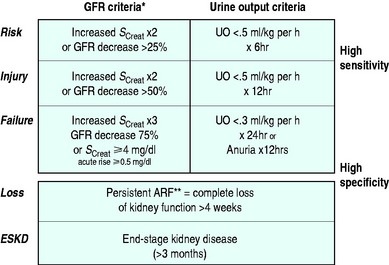

Depending on the criteria used to define its presence, ARF has been reported to occur in 15–20% of intensive care unit (ICU) patients.1 Recently a consensus definition and classification for ARF have been developed and validated in hospital and ICU patients.2–4 This definition, which goes by the acronym of RIFLE, divides renal dysfunction into the categories of risk, injury and failure (Figure 40.1) and is likely to be the dominant approach to defining ARF in ICUs for the next 5–10 years. Using this classification, the incidence of some degree of renal dysfunction has reported to be up to 67% in a recent study of > 5000 ICU patients.3 In hospital patients, the development of failure (in the RIFLE classification) increases the odds ratio of death 10 times.4

DIAGNOSIS AND CLINICAL CLASSIFICATION

PRERENAL RENAL FAILURE

This form of ARF is by far the most common in ICU. The term indicates that the kidney malfunctions predominantly because of systemic factors, which decrease GFR. For example, GFR may be decreased if renal blood flow is diminished by decreased cardiac output, hypotension or raised intra-abdominal pressure. Raised intra-abdominal pressure can be suspected on clinical grounds and confirmed by measuring bladder pressure with a urinary catheter. A pressure of > 25–30 mmHg above the pubis should prompt consideration of decompression. If the systemic cause of renal failure is rapidly removed or corrected, renal function improves and relatively rapidly returns to near-normal levels. However, if intervention is delayed or unsuccessful, renal injury becomes established and several days or weeks are then necessary for recovery. Several tests (measurement of urinary sodium, fractional excretion of sodium and other derived indices) have been promoted to help clinicians identify the development of such ‘ established’ ARF. Unfortunately, their accuracy is doubtful.5 The clinical utility of these tests in ICU patients who receive vasopressors, massive fluid resuscitation and loop diuretic infusions is low. Furthermore, it is important to observe that prerenal ARF and established ARF are part of a continuum, and their separation has limited clinical implications. The treatment is the same – treatment of the cause while promptly resuscitating the patient using invasive haemodynamic monitoring to guide therapy.

PARENCHYMAL RENAL FAILURE

This term is used to define a syndrome where the principal source of damage is within the kidney and where typical structural changes can be seen on microscopy. Disorders which affect the glomerulus or the tubule can be responsible (Table 40.1).

| Glomerulonephritis |

| Vasculitis |

| Interstitial nephritis |

| Malignant hypertension |

| Pyelonephritis |

| Bilateral cortical necrosis |

| Amyloidosis |

| Malignancy |

| Nephrotoxins |

Among these, nephrotoxins are particularly important, especially in hospital patients. The most common nephrotoxic drugs affecting ICU patients are listed in Table 40.2. Many cases of drug-induced ARF rapidly improve upon removal of the offending agent. Accordingly, a careful history of drug administration is mandatory in all patients with ARF. In some cases of parenchymal ARF, a correct working diagnosis can be obtained from history, physical examination and radiological and laboratory investigations. In such patients one can proceed to a therapeutic trial without the need to resort to renal biopsy. However, if immunosuppressive therapy is considered, renal biopsy is recommended. Renal biopsy in ventilated patients under ultrasound guidance does not carry additional risks compared to standard conditions.

Table 40.2 Drugs which may cause acute renal failure in the intensive care unit

| Radiocontrast agents |

| Aminoglycosides |

| Amphotericin |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| β-lactam antibiotics (interstitial nephropathy) |

| Sulphonamides |

| Acyclovir |

| Methotrexate |

| Cisplatin |

| Cyclosporin A |

| FK-506 (tacrolimus) |

HEPATORENAL SYNDROME

This condition is a form of ARF, which occurs in the setting of severe liver dysfunction in the absence of other known causes of ARF. Typically, it presents as progressive oliguria with a very low urinary sodium concentration (< 10 mmol/l). Its pathogenesis is not well understood. It is important to note, however, that, in patients with severe liver disease, other causes of ARF are much more common. They include sepsis, paracentesis-induced hypovolaemia, raised intra-abdominal pressure due to tense ascites, diuretic-induced hypovolaemia, lactulose-induced hypovolaemia, alcoholic cardiomyopathy, and any combination of these. The avoidance of hypovolaemia by albumin administration in patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis has been shown to decrease the incidence of renal failure in a recent randomised controlled trial (RCT).6 These causes must be looked for and promptly treated. Recent small studies suggest that a vasopressin derivative called terlipressin may improve GFR in this condition.7

RHABDOMYOLYSIS-ASSOCIATED ARF

This condition accounts for close to 5–10%8 of cases of ARF in ICU depending on the setting. Its pathogenesis involves prerenal, renal and postrenal factors. It is now typically seen following major trauma, drug overdose with narcotics, vascular embolism, and in response to a variety of agents which can induce major muscle injury. The principles of treatment are based on retrospective data, small series and multivariate logistic regression analysis, because no RCTs have been conducted. They include prompt and aggressive fluid resuscitation, elimination of causative agents, correction of compartment syndromes, the alkalinisation of urine (pH > 6.5) and the maintenance of polyuria (> 300 ml/h). The role of mannitol is controversial.

POSTRENAL RENAL FAILURE

Obstruction to urine outflow is the most common cause of functional renal impairment in the community,9 but is uncommon in the ICU. Typical causes of obstructive ARF include bladder neck obstruction from an enlarged prostate, ureteric obstruction from pelvic tumours or retroperitoneal fibrosis, papillary necrosis or large calculi. The clinical presentation of obstruction may be acute or acute-on-chronic in patients with long-standing renal calculi. It may not always be associated with oliguria. If obstruction is suspected, ultrasonography can be easily performed at the bedside. However, not all cases of acute obstruction have an abnormal ultrasound and, in many cases, obstruction occurs in conjunction with other renal insults (e.g. staghorn calculi and severe sepsis of renal origin). Assessment of the role of each factor and overall management should be conducted in conjunction with a urologist. Finally the sudden and unexpected development of anuria in an ICU patient should always suggest obstruction of the urinary catheter as the cause. Appropriate flushing or changing of the catheter should be implemented in this setting.

PATHOGENESIS OF ACUTE RENAL FAILURE

In septic patients with hyperdynamic circulations, ARF may occur in the setting of increased renal blood flow, with the loss of GFR being secondary to decreased intraglomerular pressure induced by efferent arteriolar vasodilatation.14

THE CLINICAL PICTURE

The most common clinical picture seen in ICU is that of a patient who has sustained or is experiencing a major systemic insult (trauma, sepsis, myocardial infarction, severe haemorrhage, cardiogenic shock, major surgery and the like). When the patient arrives in the ICU, resuscitation is typically well under way or surgery may have just been completed. Despite such efforts, the patient is already anuric or profoundly oliguric, the serum creatinine is rising and a metabolic acidosis is developing. Potassium and phosphate levels may be rapidly rising as well. Accompanying multiple-organ dysfunction (mechanical ventilation and need for vasoactive drugs) is common. Fluid resuscitation is typically undertaken in the ICU under the guidance of invasive hemodynamic monitoring. Vasoactive drugs are often used to restore mean arterial pressure (MAP) to ‘ acceptable’ levels (typically > 65–70 mmHg). The patient may improve over time and urine output may return with or without the assistance of diuretic agents. If urine output does not return, however, renal replacement therapy needs to be considered.

PREVENTING ACUTE RENAL FAILURE

RESUSCITATION

Intravascular volume must be maintained or rapidly restored, and this is often best done using invasive hemodynamic monitoring (central venous catheter, arterial cannula and pulmonary artery catheter or pulse contour cardiac output catheters in some cases). Oxygenation must be maintained. An adequate haemoglobin concentration (at least > 70 g/l) must be maintained or immediately restored. Once intravascular volume has been restored, some patients remain hypotensive (MAP < 70 mmHg). In these patients, autoregulation of renal blood flow may be lost. Restoration of MAP to near-normal levels may increase GFR.15,16 Such elevations in MAP, however, require the addition of vasopressor drugs.15,16 In patients with hypertension or renovascular disease, a MAP of 75–80 mmHg may still be inadequate. The nephroprotective role of additional fluid therapy in a patient with a normal or increased cardiac output and blood pressure is questionable. Despite these resuscitation measures renal failure may still develop if cardiac output is inadequate. This may require a variety of interventions from the use of inotropic drugs to the application of ventricular assist devices.

NEPHROPROTECTIVE DRUGS

‘ RENAL DOSE’ OR ‘ LOW-DOSE’ DOPAMINE

Evidence of the efficacy or safety of its administration in critically ill patients is lacking. However, this agent is a tubular diuretic and occasionally increases urine output. This may be incorrectly interpreted as an increase in GFR. Furthermore, a recent large phase III trial in critically ill patients showed low-dose dopamine to be as effective as placebo in the prevention of renal dysfunction.17

LOOP DIURETICS

These agents may protect the loop of Henle from ischaemia by decreasing its transport-related workload. Animal data are encouraging, as are ex-vivo experiments. There are no double-blind RCTs of suitable size to prove that these agents reduce the incidence of renal failure. However, there are some studies which support the view that loop diuretics may decrease the need for dialysis in patients with developing ARF.18 They appear to achieve this by inducing polyuria, which results in the prevention or easier control of volume overload, acidosis and hyperkalaemia, the three major triggers for renal replacement therapy in the ICU. Because avoiding dialysis simplifies treatment and reduces cost of care, loop diuretics are occasionally used in patients with renal dysfunction, especially in the form of continuous infusion.

OTHER AGENTS

Other agents, such as theophylline, urodilatin and anaritide (a synthetic atrial natriuretic factor), have also been proposed. Studies so far, however, have been experimental, too small or have shown no beneficial effect. In a randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, fenoldopam has been shown to attenuate the deterioration in serum creatinine typically seen in septic patients.19 Studies of this agent in other situations, however, have failed to show a benefit.20 Its role in ARF remains uncertain. Similarly, in a single-centre study, rhANF has been shown to attenuate renal injury in higher-risk patients having cardiac surgery21 but a large multicentre study of ARF failed to show a benefit.22 Many more investigations are needed in this field.

RADIOCONTRAST NEPHROPATHY

In patients receiving radiocontrast an RCT suggested that saline infusion to maintain intravascular fluid expansion is superior to the addition of mannitol or furosemide. Several RCTs of similar patients demonstrated a beneficial effect of N-acetylcysteine treatment before and after radiocontrast administration, as confirmed in a recent meta-analysis.23 Since these preventive interventions have minimal toxicity, they should be considered whenever a patient is scheduled for the administration of intravenous radiocontrast. Their effectiveness in ICU patients who have already been fluid-resuscitated remains unknown.

DIAGNOSTIC INVESTIGATIONS

An aetiological diagnosis of ARF must always be established. Such diagnosis may be obvious on clinical grounds. However, in many patients, it is best to consider all possibilities and exclude common treatable causes by simple investigations. Such investigations include the examination of urinary sediment and exclusion of a urinary tract infection (in most, if not all, patients), the exclusion of obstruction when appropriate (some patients) and the careful exclusion of nephrotoxins (all patients).

MANAGEMENT OF ESTABLISHED ACUTE RENAL FAILURE

Metabolic acidosis is almost always present but rarely requires treatment per se. Anaemia requires correction to maintain a haemoglobin of at least > 70 g/l. More aggressive transfusion needs individual patient assessment.24 Drug therapy must be adjusted to take into account the effect of the decreased clearances associated with loss of renal function. Stress ulcer prophylaxis is advisable and should be based on H2-receptor antagonists or proton pump inhibitors in selected cases. Assiduous attention should be paid to the prevention of infection.

Fluid overload can be prevented by the use of loop diuretics in polyuric patients. However, if the patient is oliguric, the only way to avoid fluid overload is to institute renal replacement therapy at an early stage (see Chapter 41). Marked azotaemia ([urea] > 40 mmol/l or [creatinine] > 400 μmol/l) is undesirable and should probably be treated with renal replacement therapy unless recovery is imminent or already under way and a return toward normal values is expected within 24–48 hours. It is recognized, however, that no RCTs exist to define the ideal time for intervention with artificial renal support.

PROGNOSIS

The mortality of critically ill patients with ARF remains high (40–80% depending on case-mix). It is frequently stated that patients die with renal failure rather than of renal failure. However, growing evidence suggests that better uraemic control and more intensive artificial renal support may improve survival by perhaps 30%.25,26 Such evidence supports a careful and proactive approach to the treatment of patients with ARF, which is based on the prevention of uncontrolled uraemia and the maintenance of low urea levels throughout the patient’s illness.

1 Chew SL, Lins RL, Daelemans R, et al. Outcome in acute renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1993;8:101-107.

2 Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA, et al. Acute renal failure – definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: the Second International Consensus Conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) Group. Crit Care. 2004;8:R204-210.

3 Hoste EAJ, Clermont G, Kersten A, et al. RIFLE criteria for acute kidney injury are associated with hospital mortality in critically ill patients: a cohort analysis. Crit Care. 2006;10:R73-83.

4 Uchino S, Bellomo R, Goldsmith D, et al. An assessment of the RIFLE criteria for acute renal failure in hospitalized patients. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1913-1917.

5 Langenberg C, Wan L, Bagshaw SM, et al. Urinary biochemistry in experimental septic acute renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:3389-3397.

6 Sort P, Navasa M, Arroyo V, et al. Effect of intravenous albumin on renal impariment and mortality in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:403-409.

7 Fabrizi F, Dixit V, Martin P. Meta-analysis: terlipressin therapy for the hepatorenal syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:935-944.

8 Uchino S, Kellum J, Bellomo R, et al. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients – a multinational, multicenter study. JAMA. 2005;294:813-818.

9 Feest TG, Round A, Hamad S. Incidence of severe acute renal failure in adults: results of a community-based study. Br Med J. 1993;306:481-483.

10 Brezis M, Rosen SN, Silva P, et al. Selective vulnerability of the medullary thick ascending limb to anoxia in the isolated perfused rat kidney. J Clin Invest. 1984;73:182-190.

11 Bonventre JV. Mechanisms of ischemic acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 1993;43:1160-1178.

12 Portilla D, Mandel LJ, Bar-Sagi D, et al. Anoxia induces phospholipase A2 activation in rabbit renal proximal tubules. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:F354-360.

13 Di Mari JF, Davis R, Safirstein RL. MAPK activation determines renal epithelial cell survival during oxidative injury. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:F195-203.

14 Langenberg C, Wan L, Egi M, et al. Renal blood flow in experimental septic acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1996-2002.

15 Bellomo R, Kellum JA, Wisniewski SR, et al. Effects of norepinephrine on the renal vasculature in normal and endotoxemic dogs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1186-1192.

16 Bersten AD, Holt AW. Vasoactive drugs and the importance of renal perfusion pressure. N Horizons. 1995;3:650-661.

17 ANZICS Clinical Trials Group. Low-dose dopamine in patients with early renal dysfunction: a placebo-controlled randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;356:2139-2143.

18 Majumdar S, Kjellstrand CM. Why do we use diuretics in acute renal failure? Semin Dialysis. 1996;9:454-459.

19 Morelli A, Ricci Z, Bellomo R, et al. Prophylactic fenoldopam for renal protection in sepsis: a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:2451-2456.

20 Bove T, Landoni G, Calabro MG, et al. Renoprotective action of fenoldopam in high-risk patients undergoing cardiac surgery: a prospective double-blind randomized clinical trial. Circulation. 2005;111:3230-3235.

21 Sward K, Valsson F, Odencrants P, et al. Recombinant human atrial natriuretic peptide in ischemic acute renal failure: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1310-1315.

22 Chertow GM, Lazarus JM, Paganini EP, et al. Predictors of mortality and the provision of dialysis in patients with acute tubular necrosis: the Auriculin Anaritide Acute Renal Failure Study Group. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9:692-698.

23 Birck R, Krzossok S, Markowetz F, et al. Acetylcysteine for prevention of contrast nephropathy. Lancet. 2003;362:598-603.

24 Hebert P, Wells G, Blajchman MA, et al. A multicenter randmized controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409-417.

25 Saudan P, Niederberger M, De Seigneux S, et al. Adding dialysis dose to continuous hemofiltration increases survival in patients with acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 2006;70:1312-1317.

26 Ronco C, Bellomo R, Homel P, et al. Effects of different doses in continuous veno-venous haemofiltration on outcomes of acute renal failure: a prospective randomized trial. Lancet. 2000;355:26-30.