Chapter 28 Acute Myocardial Infarction

1 Who is at risk for acute myocardial infarction (AMI)?

Nonmodifiable: older age, noncardiac atherosclerotic disease, first-degree relative with early atherosclerosis (male age < 55 years, female age < 65 years).

Nonmodifiable: older age, noncardiac atherosclerotic disease, first-degree relative with early atherosclerosis (male age < 55 years, female age < 65 years).

Modifiable: diabetes mellitus; hypertension; smoking; elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and triglycerides; C-reactive protein; lipoprotein (a); low HDL; hypertriglyceridemia; metabolic syndrome; sedentary lifestyle; atherogenic diet.

Modifiable: diabetes mellitus; hypertension; smoking; elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and triglycerides; C-reactive protein; lipoprotein (a); low HDL; hypertriglyceridemia; metabolic syndrome; sedentary lifestyle; atherogenic diet.

Unclear: In more than 10% of patients, no obvious risk factor is seen for coronary artery disease (CAD).

Unclear: In more than 10% of patients, no obvious risk factor is seen for coronary artery disease (CAD).

3 How are patients typically seen initially with an AMI?

Severe retrosternal pressure with radiation to arms, neck, or jaw. Usually ≥ 30 minutes in duration and associated with dyspnea, weakness, or diaphoresis. May be provoked by exertion, emotional stress, or extreme temperatures.

Severe retrosternal pressure with radiation to arms, neck, or jaw. Usually ≥ 30 minutes in duration and associated with dyspnea, weakness, or diaphoresis. May be provoked by exertion, emotional stress, or extreme temperatures.

Rales, diaphoresis, hypotension, bradycardia or tachycardia, and transient murmur of mitral regurgitation are potential physical findings, though the examination results are most often unremarkable.

Rales, diaphoresis, hypotension, bradycardia or tachycardia, and transient murmur of mitral regurgitation are potential physical findings, though the examination results are most often unremarkable.

The key considerations in differential diagnosis are aortic dissection, pulmonary embolism, and pericarditis.

The key considerations in differential diagnosis are aortic dissection, pulmonary embolism, and pericarditis.

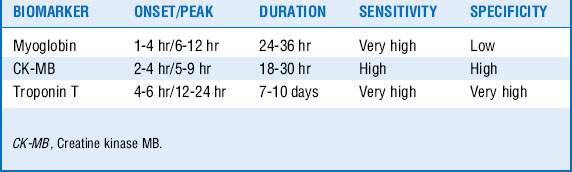

4 Which biomarkers diagnose AMI?

The recently adopted universal definition of AMI includes elevation in cardiac biomarkers above the 99th percentile of the upper reference limit. See Table 28-1.

5 How do you diagnose an ST-elevation MI (STEMI)?

New left bundle branch block or ≥ 1-mm ST elevations in two or more contiguous leads. Absence of these electrocardiogram (ECG) changes leads to the alternative diagnosis: non–ST-elevation MI (NSTEMI). Both types of MI demonstrate positive cardiac biomarkers.

New left bundle branch block or ≥ 1-mm ST elevations in two or more contiguous leads. Absence of these electrocardiogram (ECG) changes leads to the alternative diagnosis: non–ST-elevation MI (NSTEMI). Both types of MI demonstrate positive cardiac biomarkers.

Formation of a fibrin-rich red clot, which adheres to activated platelets, causing total occlusion of the affected artery and probable transmural infarction.

Formation of a fibrin-rich red clot, which adheres to activated platelets, causing total occlusion of the affected artery and probable transmural infarction.

This syndrome was formerly termed Q-wave MI, but this terminology has been abandoned in favor of the more specific STEMI term.

This syndrome was formerly termed Q-wave MI, but this terminology has been abandoned in favor of the more specific STEMI term.

6 In whom does cardiogenic shock develop?

Shock complicating MI is most common among elderly patients.

Shock complicating MI is most common among elderly patients.

Criteria for cardiogenic shock include persistent hypotension with a systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg, cardiac index < 1.8 L/min1/m2, left ventricular end-diastolic pressure > 18 mm Hg, or need for pressors or hemodynamic support.

Criteria for cardiogenic shock include persistent hypotension with a systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg, cardiac index < 1.8 L/min1/m2, left ventricular end-diastolic pressure > 18 mm Hg, or need for pressors or hemodynamic support.

Causes of cardiogenic shock include ventricular septal rupture, free wall or papillary muscle rupture, large MI, and nonischemic causes (myocarditis, takotsubo cardiomyopathy, valvular heart disease).

Causes of cardiogenic shock include ventricular septal rupture, free wall or papillary muscle rupture, large MI, and nonischemic causes (myocarditis, takotsubo cardiomyopathy, valvular heart disease).

7 What is the prognosis of a patient with AMI and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest?

The cause of cardiac arrest is AMI in ≥ 50% of patients. Other causes include nonischemic causes of arrhythmias (i.e., nonischemic cardiomyopathy).

The cause of cardiac arrest is AMI in ≥ 50% of patients. Other causes include nonischemic causes of arrhythmias (i.e., nonischemic cardiomyopathy).

Approximately 40% of patients with cardiac arrest may survive to hospital discharge. Predictors of discharge from hospital include witnessed arrest, initial ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation, bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation, cooling or hypothermia, younger age, male sex, acute myocardial ischemia or heart failure, early invasive management of CAD, and absence of comorbidities.

Approximately 40% of patients with cardiac arrest may survive to hospital discharge. Predictors of discharge from hospital include witnessed arrest, initial ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation, bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation, cooling or hypothermia, younger age, male sex, acute myocardial ischemia or heart failure, early invasive management of CAD, and absence of comorbidities.

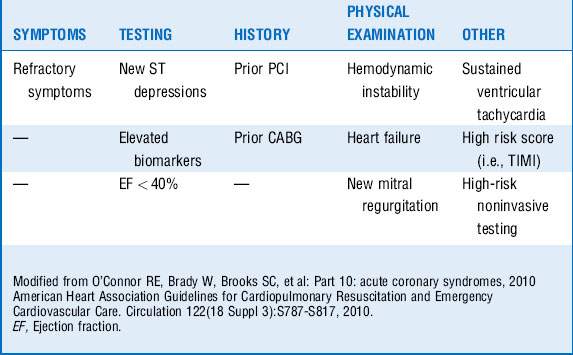

12 You are evaluating a patient with unstable angina. What patient characteristics would sway you to choose an early referral to the catheterization laboratory and possible invasive revascularization?

17 What are the indications for cooling or hypothermia after AMI and cardiac arrest?

Adult successfully resuscitated from a witnessed out-of-hospital or in-hospital cardiac arrest and now hemodynamically stable

Adult successfully resuscitated from a witnessed out-of-hospital or in-hospital cardiac arrest and now hemodynamically stable

Patient with a presenting rhythm of ventricular fibrillation or nonperfusing ventricular tachycardia who remains comatose after restoration of spontaneous circulation

Patient with a presenting rhythm of ventricular fibrillation or nonperfusing ventricular tachycardia who remains comatose after restoration of spontaneous circulation

Key Points Treatment of Acute Myocardial Infarction

1. Distinguish between unstable angina [UA]–NSTEMI and STEMI: STEMI is an occluded artery and requires immediate reperfusion with PCI or fibrinolysis; UA-NSTEMI requires medical therapy and invasive approach (within 4-48 hours of presentation) for all patients at increased risk.

2. Oral antiplatelet therapy should be initiated including aspirin and clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor.

3. Antithrombotics (heparin, enoxaparin, fondaparinux, or bivalirudin) should be administered with weight- and glomerular filtration rate–adjusted dosing to avoid bleeding risks.

4. Statin, β-blocker, and ACE inhibitors should be considered in all patients with AMI regardless of baseline LDL level, blood pressure, and heart rate.

5. Revascularization (PCI, CABG) is warranted immediately (STEMI–primary PCI) or urgently (STEMI-postlytic, pharmacoinvasive approach) or within 4 to 48 hours of presentation (high-risk UA-NSTEMI).

1 Antman E.M., Cohen M., Bernink P.J., et al. The TIMI risk score for unstable angina/non-ST elevation MI: a method for prognostication and therapeutic decision making. JAMA. 2000;284:835–842.

2 Dauerman H.L. Challenges in oral antiplatelet therapy: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104(5 Suppl):39C–43C.

3 Dauerman H.L., Sobel B.E. Synergistic treatment of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction with pharmacoinvasive recanalization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:646–651.

4 De Backer D., Biston P., Devriendt J., et al. Comparison of dopamine and norepinephrine in the treatment of shock. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:779–789.

5 Holzer M. Targeted temperature management for comatose survivors of cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1256–1264.

6 Redpath C., Sambell C., Stiell I., et al. In-hospital mortality in 13,263 survivors of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Canada. Am Heart J. 2010;159:577–583. e1

7 Reynolds H.R., Hochman J.S. Cardiogenic shock: current concepts and improving outcomes. Circulation. 2008;117:686–697.

8 Sleeper L.A., Ramanathan K., Picard M.H., et al. Functional status and quality of life after emergency revascularization for cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:266–273.

9 Stone G.W., Maehara A., Lansky A.J., et al. A prospective natural-history study of coronary atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:226–235.

10 Thygesen K., Alpert J.S., White H.D., et al. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:2173–2195.

11 White H.D., Chew D.P. Acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 2008;372:570–584.

12 Wiviott S.D., Braunwald E., McCabe C.H., et al. Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2001–2015.