Chapter 25 Acute Myeloid Leukemia in Children

Table 25-1 2008 World Health Organization Classification of Acute Myeloid Leukemia

Modified from Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, et al: The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: Rationale and important changes, Blood 114:937, 2009.

Extramedullary Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Myeloid Sarcoma and Leukemia Cutis

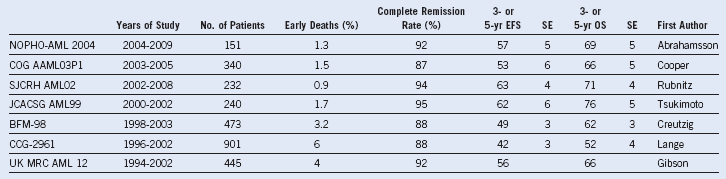

Table 25-2 Outcomes From Recent Cooperative Group Pediatric Acute Myeloid Leukemia Trials

BFM, Berlin-Frankfurt Muenster; CCG, Children’s Cancer Group; COG, Children’s Oncology Group; EFS, event-free survival; JCACSG, Japanese Childhood AML Cooperative Study Group; NOPHO, Nordic Society for Pediatric Hematology and Oncology; OS, overall survival; SE, standard error; SJCRH, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital; UK MRC, United Kingdom Medical Research Council.