Chapter 19

Acute Kidney Injury (Case 12)

Isai Gopalakrishnan Bowline MD amd Akhtar Ashfaq MD

Case: The patient is a 77-year-old man with diabetes, hypertension, and benign prostatic hypertrophy who was admitted with nausea, vomiting, and altered mental status. He was well until 2 weeks ago when he developed cough and myalgias. He was seen in a walk-in clinic and prescribed antibiotics for an upper respiratory infection (URI). Although his URI symptoms subsided, he subsequently developed loose stools and anorexia. For the past 2 days he has been unable to keep down any food, and the morning of presentation he became confused and disoriented. His family has noticed that he has not been urinating much but states that he has not been drinking much either. On exam he is hypotensive and tachycardic. Initial admission lab tests show a blood urea nitrogen (BUN) of 43 mg/dL and a creatinine (Cr) of 3.5 mg/dL.

Differential Diagnosis

Speaking Intelligently

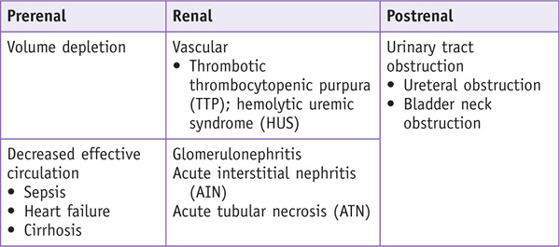

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is defined by a sudden decline in kidney function as manifested by a decrease in glomerular filtration rate (GFR). The etiologies of AKI can be divided into three categories: prerenal azotemia, postrenal azotemia, and intrinsic renal disease. Prerenal azotemia is a physiologic response to volume depletion or renal hypoperfusion. Postrenal azotemia is due to an obstruction of the urine flow from the kidney. Intrinsic azotemia is due to dysfunction of the renal parenchyma.

PATIENT CARE

Clinical Thinking

• Classify the patient based on urine output.

History

• When evaluating for prerenal azotemia, it is important to inquire about volume loss.

• Has the patient had any diarrhea, vomiting, or burns, or is he or she taking diuretics?

• Eliminating postrenal etiologies involves assessing urine output.

• Review medications for use of anticholinergic medications that may cause urinary retention.

• Consider etiologies that precipitate intrinsic renal disease.

• Inquire about recent trauma, which can precipitate rhabdomyolysis.

• Consider atheroembolic disease in patients with recent endovascular procedures.

• Review medications that may potentially cause ATN, such as the aminoglycosides.

Physical Examination

• Physical assessment of volume status is very important in evaluating the cause of AKI.

• Dry mucous membranes and hyperthermia support hypovolemia as a diagnosis.

Tests for Consideration

| Clinical Entities | Medical Knowledge |

|

Volume Depletion |

|

|

Pφ |

Volume depletion activates central baroreceptors, which results in activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, release of antidiuretic hormone (ADH), and activation of the sympathetic nervous system. These mechanisms result in systemic vasoconstriction and sodium and water retention, which maintains renal blood flow. Within the kidney, renal hypoperfusion causes dilatation of the afferent arterioles and constriction of the efferent arterioles, maintaining GFR. In cases of prolonged hypoperfusion, these mechanisms are overwhelmed and decompensation develops, resulting in decreased GFR and resultant AKI. |

|

TP |

Patients present with a history of volume loss (i.e., vomiting, diarrhea, diuretic use, bleeding). On exam they are often hypotensive, tachycardic, and orthostatic. |

|

Dx |

Expected laboratory findings include an elevated BUN and creatinine with a BUN/Cr ratio > 20 : 1, FeNa < 1%, and UNa < 20 mmol/L. Urine sediment is bland. |

|

Tx |

Restore renal blood flow. Intravenous fluids aid in returning perfusion pressures to the normal range. Crystalloids are preferred for resuscitation. Colloids such as packed-red-cell transfusions are indicated if the patient is bleeding. See Cecil Essentials 28, 32. |

|

Heart Failure |

|

|

Pφ |

Even though circulatory volume is overloaded on exam, decreased cardiac output results in a decreased effective circulation. The central baroreceptors become activated, resulting in the same neurohumoral response the body has to volume depletion. Initially the body compensates by systemic vasoconstriction with sodium and water retention, but if these mechanisms are overwhelmed, decreased GFR and AKI will develop. |

|

TP |

Patients may have extensive cardiac histories with low ejection fractions. They usually present with decompensated heart failure with jugular venous distension, pulmonary edema, and lower extremity swelling. |

|

Expected laboratory findings include an elevated BUN and creatinine with a BUN/Cr ratio > 20 : 1, FENa < 1%, and UNa < 20 mmol/L. Urine sediment is bland. |

|

|

Tx |

Restore renal blood flow by improving cardiac function. Administer diuretics to assist in decreasing the work load on the heart. Inotropic support may be necessary to augment renal perfusion in refractory cases. See Cecil Essentials 6, 28, 32. |

|

Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura/Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (TTP/HUS) |

|

|

Pφ |

TTP and HUS are characterized by fibrin and platelet thrombi in the microvasculature of various organs, primarily affecting the kidneys and brain. The inciting event appears to be injury to the endothelium, resulting in dysregulation of the coagulation/complement system and unchecked thrombosis. In typical HUS, the mechanism is associated with exotoxins found in certain bacteria that bind microvascular endothelium, leading to vascular damage and thrombi formation. With TTP and atypical forms of HUS, the underlying mechanism results from defects in proteinases or other factors that are crucial to the coagulation system. |

|

TP |

The classic findings associated with both TTP and HUS consist of thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, renal failure, neurologic symptoms, and fevers. The degree of renal failure varies between these two entities; HUS more commonly presents with overt renal failure. Neurologic symptoms include confusion, headaches, seizures, and even coma. In typical HUS, additional symptoms may include abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea. |

|

Dx |

Diagnosis is primarily based on clinical assessment of the above constellation of symptoms. The microangiopathic anemia demonstrates signs of hemolysis (i.e., elevated lactate dehydrogenase [LDH], low haptoglobin, elevated bilirubin). Schistocytes can be seen on examination of the peripheral smear. |

|

Although the pathology is similar for both of these disorders, distinguishing between them is crucial to management. Plasmapheresis/plasma exchange is considered first-line therapy in patients with TTP and atypical HUS. Additional treatment modalities include intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), plasma infusion, and steroids. Patients with typical Shiga toxin–induced HUS fare well with supportive management. See Cecil Essentials 29, 31, 32. |

|

|

Glomerulonephritis |

|

|

Pφ |

Acute glomerulonephritis (GN) occurs as a result of glomerular inflammation. When the inflammation is so profound that it causes renal failure in days to weeks, the syndrome is called rapidly progressive GN. The pathologic finding in acute GN is cellular proliferation around the glomerular tuft, which is termed crescent formation. Crescent formation occurs when glomerular injury results in breaks in the glomerular basement membrane, allowing deposition of fibrin in Bowman space. The fibrin deposition causes epithelial cell proliferation and macrophage infiltration, which results in crescent formation. The etiologies of acute GN are varied and include both vasculitides (e.g., Wegener granulomatosis, microscopic polyangiitis) and immune complex diseases (e.g., SLE, post-streptococcal GN, endocarditis, IgA nephropathy). |

|

TP |

Patients with acute GN typically present with hypertension, proteinuria, microscopic hematuria, and acute renal failure (ARF). The ARF can be oliguric or nonoliguric. If the acute GN is part of a systemic illness such as lupus or endocarditis, the patient will have additional symptoms suggestive of those clinical entities. |

|

Dx |

Expected laboratory findings include an elevated BUN and creatinine. The urinalysis reveals an active urine sediment with microscopic hematuria, proteinuria, and red blood cell casts. A serologic evaluation and a kidney biopsy are often necessary to determine the cause of the acute GN. |

|

Tx |

The treatment of an acute GN depends on the underlying cause. When acute GN is due to a systemic illness, such as endocarditis or streptococcal infection, the underlying condition should be treated. When the acute GN is the result of an autoimmune disease, such as lupus or Wegener granulomatosis, the treatment often requires immunosuppressive medications. See Cecil Essentials 29, 32. |

|

Pφ |

The histologic finding in AIN is an inflammatory cell infiltrate within the renal interstitium in response to a medication or infection. The inflammatory cell infiltrate, which is made up primarily of lymphocytes, leads to interstitial edema and tubular damage. Although the provoking factor varies, animal studies have shown that both cellular and humoral mechanisms are important in its pathogenesis. |

|

TP |

Patients with drug-induced AIN present with ARF occurring days to weeks after starting a new medication. The ARF can range from mild elevations in creatinine to oliguric renal failure requiring dialysis. Affected individuals may report associated fevers, rash, arthralgias, or flank pain. |

|

Dx |

Expected laboratory findings include an elevated BUN and creatinine. Urinary sediment typically reveals microscopic hematuria, non-nephritic–range proteinuria, pyuria, and WBC casts. Eosinophiluria is a hallmark of this disease but also can be seen with other renal injuries. Definitive diagnosis can be made only through renal biopsy. |

|

Tx |

Management is primarily supportive, requiring discontinuation of the offending agent. Corticosteroid therapy has been employed in more severe cases of AIN and may hasten recovery. Often a renal biopsy definitively diagnosing AIN is mandated before beginning therapy. See Cecil Essentials 27, 30, 32. |

|

Acute Tubular Necrosis |

|

|

Pφ |

ATN can be caused by prolonged hypoperfusion, exogenous nephrotoxins (medications, contrast agents), or endogenous nephrotoxins (myoglobin, hemoglobin, or uric acid), resulting in direct tubular damage and irreversible cellular injury. ATN commonly occurs within a hospital setting. |

|

TP |

Ischemia is the most common cause of ATN, and affected patients may present with hypotension and marked volume depletion. When ATN is the result of a nephrotoxic injury, the patient will often have a history of a recent contrast study, evidence of trauma, or a history of tumor lysis syndrome. |

|

Laboratory studies show an elevated BUN and creatinine with a BUN/Cr ratio < 20 : 1. In addition, high UNa and an FENa >1% characterize ATN. The urine sediment shows tubular epithelial cells and granular casts. A definitive diagnosis can be made with renal biopsy but is rarely necessary. |

|

|

Tx |

Most cases of ATN resolve once the offending agent is removed. In the setting of rhabdomyolysis and tumor lysis syndrome, intravenous hydration may prevent the tubular damage. Depending on the severity of tubular damage and level of preexisting renal function, hemodialysis may have to be initiated. See Cecil Essentials 32. |

|

Urinary Tract Obstruction |

|

|

Pφ |

Obstruction at any level of the urinary tract, irrespective of the etiology, will increase pressure in the collecting systems resulting in compensatory dilatation proximal to the lesion. If left untreated, this will result in a decreased net glomerular filtration pressure and overall decline in GFR. The extent of injury is determined by the severity and duration of the obstruction. |

|

TP |

Presentations may vary widely. Patients may give a history of flank or suprapubic tenderness depending on the etiology and site of obstruction. If obstruction is complete, anuria may be reported. Patients with partial obstruction may complain of urgency or frequency. Obstruction is commonly seen in patients with enlarged prostates, history of stones, or neurogenic bladders. |

|

Dx |

Laboratory findings include an elevated creatinine. Chemistries may reveal hyperkalemia and suggest type IV renal tubular acidosis (RTA). Sonography of the kidneys and bladder will show the site of obstruction. |

|

Tx |

For bladder outlet obstruction, placement of a urinary catheter is usually sufficient. If a catheter cannot be placed, a suprapubic cystostomy can be employed. Ureteral obstruction is treated with cystoscopy and stent placement, or placement of percutaneous nephrostomy tubes. See Cecil Essentials 30, 32. |

Many medications have been associated with renal failure through a variety of mechanisms. It is important to be aware of the common culprits when evaluating patients with AKI. In addition to reviewing medication lists with patients, always inquire about over-the-counter medications, herbal preparations, and vitamins. Often patients do not divulge this information without being prompted. Below is a list of common drugs implicated in renal failure.*

*There are many more agents associated with renal injury; this list is not comprehensive.

Practice-Based Learning and Improvement: Evidence-Based Medicine

Title

Mortality after acute renal failure: models for prognostic stratification and risk adjustment

Authors

Chertow GM, Soroko SH, Paganini EP, et al.

Reference

Kidney Int 2006;70:1120–1126. ©2006 Nature Publishing Group

Problem

Acute renal failure in critically ill patients

Intervention

Identifying clinical predictors of mortality in acute renal failure

Outcome/effect

PICARD study is a comprehensive analysis of demographic and clinical factors associated with mortality in 618 patients in ARF evaluated at three discrete time points. On the day of ARF diagnosis, advanced age, liver failure, and high BUN were associated with increased mortality; however, these factors were not statistically significant early in the course. On the day of consultation, advanced age, liver failure, high BUN, Cr less than 2 mg/dL, low urine output, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), sepsis, and thrombocytopenia were all associated with poor outcomes. On the day of dialysis initiation, advanced age, liver failure, high BUN, and Cr less than 2 mg/dL were significant predictors of death. Of note, low urine output did not correlate with mortality.

Historical significance/comments

Ability to predict mortality in patients with ARF will enable physicians, patients, and family members to more appropriately make management decisions.

Interpersonal and Communication Skills

Communicate Clearly about Risks and Benefits of Hemodialysis

Given the varied clinical manifestations and outcomes in patients with AKI, it is imperative that physicians communicate effectively regarding the specific disease process, prognosis, and treatment options. Such knowledge allows patients to make informed decisions regarding their management, specifically when the initiation of hemodialysis is a consideration. The physician must ensure that patients understand the risks of dialysis, such as hemodynamic instability, rapid fluid/electrolyte shifts, and infections, as well as the potential permanence of the treatment. All risks and benefits should be thoroughly reviewed and all questions clearly addressed. In cases of critically ill patients who are unable to participate in the decision-making process, physicians should educate the appropriate family members.

Demonstrate Societal Responsibility with Respect to Allocation of Finite Resources

Physicians are under constant pressure to not only meet the individual needs of patient care but also provide cost-effective management in a setting of limited resources. Nephrologists are often asked to evaluate terminally ill patients for hemodialysis. In these cases it may be evident that hemodialysis will only prolong the dying process. It is the physician’s professional responsibility to consider appropriate allocation of resources. This prevents any unnecessary treatment that not only exposes patients to avoidable harm and expense, but also diminishes the resources available for others. In these cases it is imperative that the physician has a clear and honest discussion with the patient regarding his or her overall prognosis.

Systems-Based Practice

Contrast-induced Nephropathy (CIN): Know the Benefits and Risks of Diagnostic Testing

CIN has become a significant source of hospital morbidity and mortality. With the increasing use of contrast dye in diagnostic imaging and interventional procedures, CIN has become a common cause of hospital-acquired AKI. Researchers have explored prophylactic measures to prevent onset of CIN, such as the use of N-acetylcysteine, sodium bicarbonate, and IV fluids. In addition, as a quality improvement initiative, much investigation has focused on identifying patients most at risk for developing CIN. It has been noted that patients with preexisting kidney disease, age over 75 years, and diabetes appear to be at highest risk of renal injury. Other notable risk factors include congestive heart failure, left ventricular dysfunction (ejection fraction < 40%), hypertension, use of an ACE inhibitor, and periprocedural hypotension. With this knowledge, nephrologists and radiologists are able to minimize risk in these individuals.