Chapter 377 Acute Inflammatory Upper Airway Obstruction (Croup, Epiglottitis, Laryngitis, and Bacterial Tracheitis)

The lumen of an infant’s or child’s airway is narrow; because airway resistance is inversely proportional to the 4th power of the radius (Chapter 365), minor reductions in cross-sectional area due to mucosal edema or other inflammatory processes cause an exponential increase in airway resistance and a significant increase in the work of breathing. The larynx is composed of 4 major cartilages (epiglottic, arytenoid, thyroid, and cricoid cartilages, ordered from superior to inferior) and the soft tissues that surround them. The cricoid cartilage encircles the airway just below the vocal cords and defines the narrowest portion of the upper airway in children <10 yr of age.

Inflammation involving the vocal cords and structures inferior to the cords is called laryngitis, laryngotracheitis, or laryngotracheobronchitis, and inflammation of the structures superior to the cords (i.e., arytenoids, aryepiglottic folds [“false cords”], epiglottis) is called supraglottitis. The term croup refers to a heterogeneous group of mainly acute and infectious processes that are characterized by a bark-like or brassy cough and may be associated with hoarseness, inspiratory stridor, and respiratory distress. Stridor is a harsh, high-pitched respiratory sound, which is usually inspiratory but can be biphasic and is produced by turbulent airflow; it is not a diagnosis but a sign of upper airway obstruction (Chapter 366). Croup typically affects the larynx, trachea, and bronchi. When the involvement of the larynx is sufficient to produce symptoms, they dominate the clinical picture over the tracheal and bronchial signs. Traditionally, a distinction has been made between spasmodic or recurrent croup and laryngotracheobronchitis. Some clinicians believe that spasmodic croup might have an allergic component and improves rapidly without treatment, whereas laryngotracheobronchitis is always associated with a viral infection of the respiratory tract. Others believe that the signs and symptoms are similar enough to consider them within the spectrum of a single disease, in part because studies have documented viral etiologies in both acute and recurrent croup.

377.1 Infectious Upper Airway Obstruction

Etiology and Epidemiology

With the exceptions of diphtheria, bacterial tracheitis, and epiglottitis, most acute infections of the upper airway are caused by viruses. The parainfluenza viruses (types 1, 2, and 3; Chapter 251) account for ∼75% of cases; other viruses associated with croup include influenza A and B, adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and measles. Influenza A has been associated with severe laryngotracheobronchitis. Mycoplasma pneumoniae has rarely been isolated from children with croup and causes mild disease (Chapter 215). Most patients with croup are between the ages of 3 mo and 5 yr, with the peak in the 2nd yr of life. The incidence of croup is higher in boys; it occurs most commonly in the late fall and winter but can occur throughout the year. Recurrences are frequent from 3-6 yr of age and decrease with growth of the airway. Approximately 15% of patients have a strong family history of croup.

In the past, Haemophilus influenzae type b was the most commonly identified etiology of acute epiglottitis. Since the widespread use of the HiB vaccine, invasive disease due to H. influenzae type b in pediatric patients has been reduced by 80-90% (Chapter 186). Therefore, other agents, such as Streptococcus pyogenes, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Staphylococcus aureus, now represent a larger portion of pediatric cases of epiglottitis in vaccinated children. In the prevaccine era, the typical patient with epiglottitis due to H. influenza type b was 2-4 yr of age, although cases were seen in the 1st year of life and in patients as old as 7 yr of age. The typical patient with epiglottitis is an adult with a sore throat, although cases still do occur in underimmunized children; vaccine failures have been reported.

Clinical Manifestations

Croup (Laryngotracheobronchitis)

Croup is a clinical diagnosis and does not require a radiograph of the neck. Radiographs of the neck can show the typical subglottic narrowing, or steeple sign, of croup on the posteroanterior view (Fig. 377-1). However, the steeple sign may be absent in patients with croup, may be present in patients without croup as a normal variant, and may rarely be present in patients with epiglottitis. The radiographs do not correlate well with disease severity. Radiographs should be considered only after airway stabilization in children who have an atypical presentation or clinical course. Radiographs may be helpful in distinguishing between severe laryngotracheobronchitis and epiglottitis, but airway management should always take priority.

Acute Epiglottitis (Supraglottitis)

The diagnosis requires visualization of a large, cherry red, swollen epiglottis by laryngoscopy. Occasionally, the other supraglottic structures, especially the aryepiglottic folds, are more involved than the epiglottis itself. In a patient in whom the diagnosis is certain or probable based on clinical grounds, laryngoscopy should be performed expeditiously in a controlled environment such as an operating room or intensive care unit. Anxiety-provoking interventions such as phlebotomy, intravenous line placement, placing the child supine, or direct inspection of the oral cavity should be avoided until the airway is secure. If epiglottitis is thought to be possible but not certain in a patient with acute upper airway obstruction, the patient can undergo lateral radiographs of the upper airway first. Classic radiographs of a child who has epiglottitis show the thumb sign (Fig. 377-2). Proper positioning of the patient for the lateral neck radiograph is crucial in order to avoid some of the pitfalls associated with interpretation of the film. Adequate hyperextension of the head and neck is necessary. In addition, the epiglottis can appear to be round if the lateral neck is taken at an oblique angle. If the concern for epiglottitis still exists after the radiographs, direct visualization should be performed. A physician skilled in airway management and use of intubation equipment should accompany patients with suspected epiglottitis at all times. An older cooperative child might voluntarily open the mouth wide enough for a direct view of the inflamed epiglottis.

Acute Infectious Laryngitis

Laryngitis is a common illness. Viruses cause most cases; diphtheria is an exception but is extremely rare in developed countries (Chapter 180). The onset is usually characterized by an upper respiratory tract infection during which sore throat, cough, and hoarseness appear. The illness is generally mild; respiratory distress is unusual except in the young infant. Hoarseness and loss of voice may be out of proportion to systemic signs and symptoms. The physical examination is usually not remarkable except for evidence of pharyngeal inflammation. Inflammatory edema of the vocal cords and subglottic tissue may be demonstrated laryngoscopically. The principal site of obstruction is usually the subglottic area.

Differential Diagnosis

These 4 syndromes must be differentiated from one another and from a variety of other entities that can present as upper airway obstruction. Bacterial tracheitis is the most important differential diagnostic consideration and has a high risk of airway obstruction. Diphtheritic croup is extremely rare in North America, although a major epidemic of diphtheria occurred in countries of the former Soviet Union beginning in 1990 from the lack of routine immunization. Early symptoms of diphtheria include malaise, sore throat, anorexia, and low-grade fever. Within 2-3 days, pharyngeal examination reveals the typical gray-white membrane, which can vary in size from covering a small patch on the tonsils to covering most of the soft palate. The membrane is adherent to the tissue, and forcible attempts to remove it cause bleeding. The course is usually insidious, but respiratory obstruction can occur suddenly. Measles croup almost always coincides with the full manifestations of systemic disease and the course may be fulminant (Chapter 238).

Sudden onset of respiratory obstruction can be caused by aspiration of a foreign body (Chapter 379). The child is usually 6 mo-3 yr of age. Choking and coughing occur suddenly, usually without prodromal signs of infection, although children with a viral infection can also aspirate a foreign body. A retropharyngeal or peritonsillar abscess can mimic respiratory obstruction (Chapter 374). CT scans of the upper airway are helpful in evaluating the possibility of a retropharyngeal abscess. A peritonsillar abscess is often a clinical diagnosis. Other possible causes of upper airway obstruction include extrinsic compression of the airway (laryngeal web, vascular ring) and intraluminal obstruction from masses (laryngeal papilloma, subglottic hemangioma); these tend to have chronic or recurrent symptoms.

Treatment

Acute laryngeal swelling on an allergic basis responds to epinephrine (1:1,000 dilution in dosage of 0.01 mL/kg to a maximum of 0.5 mL/dose) administered intramuscularly or racemic epinephrine (dose of 0.5 mL of 2.25% racemic epinephrine in 3 mL of normal saline) (Chapter 143). Corticosteroids are often required (2-4 mg/kg/24 hr of prednisone). After recovery, the patient and parents should be discharged with a preloaded syringe of epinephrine to be used in emergencies. Reactive mucosal swelling, severe stridor, and respiratory distress unresponsive to mist therapy may follow endotracheal intubation for general anesthesia in children. Racemic epinephrine and corticosteroids are helpful.

Tracheotomy and Endotracheal Intubation

Endotracheal intubation or tracheotomy is required for most patients with bacterial tracheitis and all young patients with epiglottitis. It is rarely required for patients with laryngotracheobronchitis, spasmodic croup, or laryngitis. Severe forms of laryngotracheobronchitis that require intubation in a high proportion of patients have been reported during severe measles and influenza A virus epidemics. Assessing the need for these procedures requires experience and judgment because they should not be delayed until cyanosis and extreme restlessness have developed (Chapter 65).

Borland ML, Babl FE, Sheriff N, et al. Croup management in Australia and New Zealand: a PREDICT study of physician practice and clinical practice guidelines. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24:452-456.

Bjornson CL, Johnson DW. Croup. Lancet. 2008;371:329-338.

Bjornson CL, Klassen TP, Williamson J, et al. A randomized trial of a single dose of oral dexamethasone for mild croup. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1306-1313.

Cherry JD. Croup. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:384-391.

Everard ML. Acute bronchiolitis and croup. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2009;56:119-133. x–xi

Geelhoed GC, Turner J, MacDonald WB. Efficacy of a small single dose of oral dexamethasone for outpatient croup: a double blind placebo controlled trial. Br Med J. 1996;313:140-142.

Kristjansson S, Berg-Kelly K, et al. Inhalation of racemic adrenaline in the treatment of mild and moderately severe croup: clinical symptom score and oxygen saturation measurements for evaluation of treatment effects. Acta Pediatr. 1994;83:1156-1160.

Ledwith CA, Shea LM, Mauro RD. Safety and efficacy of nebulized racemic epinephrine in conjunction with oral dexamethasone and mist in the outpatient treatment of croup. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;25:331-337.

Luria JW, Gonzalez-del-Rey JA, DiBiulio GA, et al. Effectiveness of oral or nebulized dexamethasone for children with mild croup, Pediatr. Adolesc Med. 2001;155:1340-1345.

Moore M, Little P. Humidified air inhalation for treating croup: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fam Pract. 2007;24(4):295-301.

Rihkanen H, Beng ER, Nieminen T, et al. Respiratory viruses in laryngeal croup of young children. J Pediatr. 2008;152:661-665.

Rittichier KK, Ledwith CA. Outpatient treatment of moderate croup with dexamethasone: intramuscular versus oral dosing. Pediatrics. 2000;106:1344-1348.

Scolnik D, Coates AL, Stephens D, et al. Controlled delivery of high vs low humidity vs mist therapy for croup in emergency departments. JAMA. 2006;295:1274-1280.

Sparrow A, Geelhoed G. Prednisolone versus dexamethasone in croup: a randomized equivalence trial. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:580-583.

Waisman Y, Klein BL, Boenning DA, et al. Prospective randomized double-blind study comparing L-epinephrine and racemic epinephrine aerosols in the treatment of laryngotracheitis. Pediatrics. 1992;89:302-306.

Wall SR, Wat D, Spiller OB, et al. The viral aetiology of croup and recurrent croup. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:359-360.

Walner DL, Ouanounou S, Donnelly LF, et al. Utility of radiographs in the evaluation of pediatric upper airway obstruction. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1999;108:378-383.

Weber JE, Chudnofsky CR, Younger JG, et al. A randomized comparison of helium-oxygen mixture (Heliox) and racemic epinephrine for the treatment of moderate to severe croup. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E96.

Adams WG, Deaver KA, Cochi SL, et al. Decline in childhood Haemophilus influenzae type b (HiB) in the HiB vaccine era. JAMA. 1993;269:221-226.

Frantz TD, Rasgon BM. Acute epiglottitis: changing epidemiologic patterns. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;109:457-460.

Gorelick MH, Baker MD. Epiglottitis in children, 1979 through 1992: effects of Haemophilus influenzae type b immunization. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1994;148:47-50.

Hickerson SL, Kirby RS, Wheeler JG, et al. Epiglottitis: a 9-year case review. South Med J. 1996;89:487-490.

Kulick RM, Selbst SM, Baker MD, et al. Thermal epiglottitis after swallowing hot beverages. Pediatrics. 1988;81:441-444.

Murrage KJ, Janzen VD, Ruby RR. Epiglottitis: adult and pediatric comparisons. J Otolaryngol. 1988;17:194-198.

Senior BA, Radkowski D, MacArthur C, et al. Changing patterns in pediatric epiglottis: a multi-institutional review, 1980 to 1992. Laryngoscope. 1994;104:1314-1322.

377.2 Bacterial Tracheitis

Diagnosis

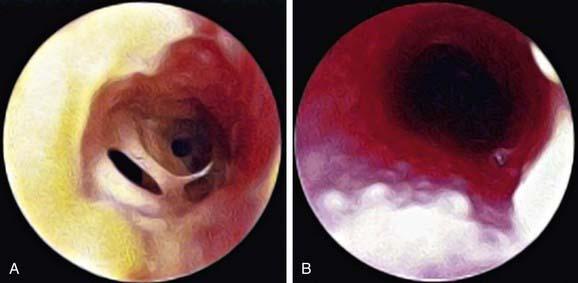

The diagnosis is based on evidence of bacterial upper airway disease, which includes high fever, purulent airway secretions, and an absence of the classic findings of epiglottitis. X-rays are not needed but can show the classic findings (Fig. 377-3); purulent material is noted below the cords during endotracheal intubation (Fig. 377-4).

Complications

Chest radiographs often show patchy infiltrates and can show focal densities. Subglottic narrowing and a rough and ragged tracheal air column can often be demonstrated radiographically. If airway management is not optimal, cardiorespiratory arrest can occur. Toxic shock syndrome has been associated with staphylococcal tracheitis (Chapter 174.2).

Donnelly LF. Diagnostic imaging pediatrics. Salt Lake City: Amirys; 2005.

Eckel HE, Widemann B, Damm M, et al. Airway endoscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of bacterial tracheitis in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1993;27:147-157.

Faden H. The dramatic change in the epidemiology of pediatric epiglottitis. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22:443-444.

Graf J, Stein F. Tracheitis in pediatric patients. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2006;17:11-13.

Huang YL, Peng CC, Chiu NC, et al. Bacterial tracheitis in pediatrics: 12 year experience at a medical center in Taiwan. Pediatr Int. 2009;51:110-113.

Salamone FN, Bobbitt DB, Myer CM, et al. Bacterial tracheitis reexamined: is there a less severe manifestation? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131:871-876.

Tebruegge M, Pantazidou A, Thorburn K, et al. Bacterial tracheitis: a multi-centre perspective. Scand J Infect Dis. 2009;28:1-10.