13 Acute diarrhoea

Case

A 70-year-old man presents with crampy, left-sided abdominal pain and bloody diarrhoea for 7 days. The patient has a background history of ischaemic heart disease and peripheral vascular disease. He also has bronchiectasis requiring regular courses of antibiotics.

Introduction

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiological mechanisms resulting in acute or chronic diarrhoea can be divided into several major groups: osmotic, secretory, exudative and abnormal motility (see Box 13.1).

Osmotic diarrhoea results when a non-absorbable solute accumulates within the small intestine. The osmolality of the small intestine is adjusted to that of plasma by water influx across the small bowel and watery diarrhoea results. Examples of osmotic diarrhoea include carbohydrate malabsorption (such as lactase deficiency) and ingestion of magnesium salts. Osmotic diarrhoea ceases when the poorly absorbed solute is removed from the diet.

The fourth major cause is increased transit in the small bowel or colon: abnormal intestinal motility. Increased transit may occur with thyrotoxicosis (due to excess thyroid hormone), diabetes mellitus or in the irritable bowel syndrome (Ch 7).

Clinical Approach to Acute Diarrhoea

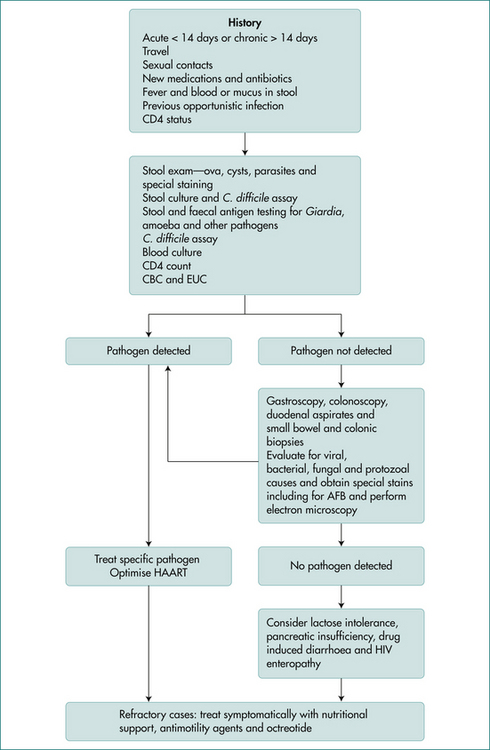

The causes of diarrhoea vary depending on the type of practice, but in all settings gastrointestinal infections are a common cause of acute diarrhoea (Box 13.2). It is clinically useful to divide acute causes of diarrhoea into clinical syndromes, watery (non-inflammatory) diarrhoea, blood (inflammatory) diarrhoea, food poisoning, diarrhoea in the traveller, diarrhoea associated with recent antibiotics or other drug use and diarrhoea in the HIV-positive (Fig 13.1) or male homosexual patient. Overlap may occur between the categories. Of course, an illness may begin as watery diarrhoea, only to progress to bloody diarrhoea later.

The clinical approach to those with acute diarrhoea should focus initially on:

History

A careful history is important in evaluating patients with acute diarrhoea and in separating minor from severe illness. Features that suggest the diarrhoea may not be self-limiting include severe diarrhoea, blood in the stool, severe abdominal pain or a high fever (Box 13.2).

Ask about the duration of symptoms as well as severity. An abrupt onset of diarrhoea, which then gradually improves, suggests an infective process. Systemic features with infectious diarrhoea include fever, myalgia, malaise, nausea and vomiting. The onset of diarrhoea with food poisoning is often severe but short-lived. With prolonged watery diarrhoea, volume depletion is more likely to develop, especially when there is associated vomiting. Large volume, watery diarrhoea may be of small bowel origin. The presence of blood in the stool is usually due to an intestinal inflammatory process (see Box 13.3).

Investigations

Those with minor resolving diarrhoea need no investigations and no specific therapy beyond maintenance of hydration. Those with features outlined in Box 13.2, where a definitive diagnosis is likely to alter management and outcome, should usually be further investigated. Those diagnostic tests should be targeted, where possible, towards a specific diagnosis according to clues from the history and physical examination.

Stool examination

Specific testing for various pathogens should be requested where appropriate. If the epidemiological settings suggest the possibility of C. difficile infection, a specific request for that pathogen as well as C. difficile toxin should be made. Viral cultures may need to be considered in immunocompromised patients.

Therapy

Antibiotics

Antibiotics should be avoided in the routine treatment of acute diarrhoea. They are usually ineffective in reducing the duration of the illnesses and in some cases may prolong excretion of the pathogen. They also have significant side effects and indiscriminate use will increase drug resistance. There are a limited number of situations where antibiotics may be helpful. Box 13.4 outlines the indication for antibiotics and these are discussed in more detail under disease headings.

Conditions Causing Food-borne Illnesses

Food-borne illnesses are caused by the consumption of contaminated food and result in significant worldwide morbidity and mortality. They can be caused by the consumption of bacteria or bacterial toxins, viruses, parasites or chemicals.

Some of the common causes of food-borne illnesses are discussed below under aetiological headings.

Bacterial food-borne illnesses

Vibrio parahaemolyticus

V. parahaemolyticus is associated with seafood and causes food poisoning outbreaks after the ingestion of shellfish or raw fish. It causes explosive watery diarrhoea with an incubation period of 12–24 hours. The diarrhoea may be associated with nausea, vomiting and fever and occurs in about 25% of patients. Occasionally, a dysenteric syndrome may result with blood diarrhoea. A specific request must be made to the laboratory for culturing the organism. Symptoms are generally short-lived and require no specific therapy.

Travellers’ Diarrhoea

Aetiology and transmission

Travellers’ diarrhoea is predominantly due to gastrointestinal infective illnesses, with an enteropathogen being documented in up to 80% of cases (Table 13.1). Causes vary considerably with country of destination, but the commonest pathogen isolated in most studies is enterotoxigenic E. coli, which accounts for up to 50% of travellers’ diarrhoea. In about 20% of cases no pathogen is isolated and this group may represent known pathogens not identified due to insensitive or inadequate culture technique, unknown pathogens or non-infectious causes of diarrhoea, such as stress, alcohol and medications.

Clinical manifestations

The onset of travellers’ diarrhoea is usually abrupt, with symptoms beginning within 3–4 days of arrival at the country of destination. Typically, the illness is mild, with less than six bowel actions daily, and it lasts 3–4 days in 85% of untreated sufferers. Occasionally, symptoms may be more severe with profuse watery diarrhoea leading to dehydration, or are associated with a high fever and blood in the stool. The presence of blood suggests invasive disease (see ‘Conditions causing acute blood diarrhoea’ later in this chapter).

Conditions Causing Acute Watery Diarrhoea

Giardia lamblia

Clinical manifestations

Ingestion of G. lamblia cysts results in a spectrum of symptoms, ranging from asymptomatic cyst passage to an acute diarrhoeal illness or chronic diarrhoea with malabsorption. After an incubation period of 1–2 weeks, a minority of patients will develop a symptomatic infection with prolonged passage of cysts. Those who develop symptoms will report watery diarrhoea with crampy abdominal pain, nausea and excessive flatus. The stools are often malodorous and may develop typical features of malabsorption, becoming greasy, bulky, pale and floating. The symptoms usually settle after 1–3 weeks but prolonged infection with marked weight loss has been reported. Blood and pus are not found in the stool and fever is not a feature of the illness.

Cholera

Treatment

Parenteral killed whole cell vaccine provides less than 50% protection and is not recommended. Newer oral vaccines may provide an increased level of protection and, since the B subunit of cholera is antigenically similar to the heat labile enterotoxin of ETEC (enterotoxigenic E. coli) it may provide a dual protection but the cost–benefit ratio needs to be considered.

Conditions Causing Acute Blood Diarrhoea

The differential diagnosis is summarised in Box 13.3.

Shigella spp.

Diagnosis

A patchy colitis with ulceration may be demonstrated at sigmoidoscopy and biopsies will help to exclude inflammatory bowel disease and amoebic colitis.

Non-typhoidal salmonellosis

The incubation of S. enteritidis is short, within the range of 24–48 hours. There is a spectrum of symptoms ranging from mild diarrhoea to severe watery diarrhoea with cramping abdominal pain and fever. Risk factors for severe disease or complications include extremes of age, haemolytic disease, immunocompromised hosts and the presence of prosthetic devices (Box 13.5).

Complications include bacteraemia, osteomyelitis, localised abscesses, meningitis and pneumonia.

Treatment

Maintenance of hydration with fluid and electrolyte replacement is indicated, as appropriate. The routine use of antibiotics should be avoided, as they do not shorten the average illness and may prolong excretion of the organisms. Antibiotics should be reserved for those with severe symptoms or at risk of complications (see Box 13.5). Antimicrobial resistance is an emerging problem. Antibiotics that are effective include quinolones, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and amoxicillin.

Typhoid fever

Clinical manifestations

The fever is persistent over a period of 4 weeks with the illness becoming more severe during the second and third week: persistent high fever, delirium and complications from waves of bacteraemia including meningitis, nephritis, osteomyelitis and hepatitis. Diarrhoea may develop at this stage of the disease with haemorrhage or perforation.

Symptoms generally start to abate after the third week, but relapses may occur.

Yersinia enterocolitica

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is established by culture of the organism, usually in the stool. It may also be cultured from atypical cases at surgery from lymph nodes or from free peritoneal fluid. Serological tests are also available, but their sensitivity and specificity are serotype-dependent, can cross-react with other bacteria and other inflammatory conditions and their titre can fluctuate in individuals with chronic sequelae.

Entamoeba histolytica

Occurrence and transmission

There is a worldwide distribution of E. histolytica with a prevalence ranging from 1% in industrialised nations up to 50% in some developing nations. The cystic form can survive in the environment and is responsible for spread of the disease via the faecal–oral route. Direct person-to-person transmission is usual, but food- and waterborne spread can occur. Several other species of amoebae, including E. dispar, reside in the lumen of the large intestine and are non-pathogenic but need to be distinguished from E. histolytica.

Antibiotic-associated Diarrhoea and C. difficle Colitis

Clinical manifestations

Those who develop symptoms usually do so during or shortly after antibiotic therapy. The illness begins as diarrhoea with cramping abdominal pain. A low-grade fever may be present together with lower abdominal tenderness. A small proportion of patients progress to colitis, which may become life-threatening, with severe bloody diarrhoea, diffuse abdominal tenderness and abdominal distension. Fulminating colitis with toxic megacolon has been reported.

Diarrhoea Associated with AIDS

Aetiology

Potential pathogens involved in AIDS diarrhoea are listed in Table 13.2 and vary with the stage of the illness and degree of immunocompetence of the host. Some patients with AIDS develop diarrhoea without any detectable pathogens and non-infectious causes of diarrhoea, including drugs, pancreatic insufficiency and tumour invasion, may be involved. The AIDS virus itself and small bowel bacterial overgrowth may also be responsible for diarrhoea in some patients.

| Source | Rate (%) |

|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | 50 |

| Shigella spp. | 10 |

| Salmonella spp. | 5 |

| Campylobacter jejuni | 3 |

| Yersinia enterocolitica | 2 |

| Entamoeba histolytica | 1 |

| Giardia lamblia | 4 |

| Cryptosporidium parvum | 3 |

| Viruses | 3 |

| Unknown | 19 |

Table 13.2 Pathogens associated with AIDS diarrhoea

| Bacterium | Virus | Protozoan |

|---|---|---|

| Myocobacterium avium–intracellulare (MAI) | Cytomegalovirus | Cryptosporidium parvum |

| Salmonella spp. | Herpes simplex virus | Giardia lamblia |

| Shigella spp. | Adenovirus | Isospora belli |

| Campylobacter jejuni | Entamoeba histolytica | |

| Clostridium difficile | Microsporidium spp. |

Key Points

Butzler J.P. Campylobacter, from obscurity to celebrity. Clin Microbio Infect. 2004;10:868-876.

Cello J.P., Day L.W. Idiopathic AIDS enteropathy and treatment of gastrointestinal opportunistic pathogens. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1952-1965.

Clark B., McKendrick M. A review of viral gastroenteritis. Curr Opinion Infect Dis. 2004;17:461-469.

Gore J.I., Surawicz C. Severe acute diarrhoea. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2003;32:1249-1267.

Greenbergand H.B., Estes M.K. Rotavirus: from pathogenesis to vaccination. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1939-1951.

Jabbar A., Wright R.A. Gastroenteritis and antibiotic associated diarrhea. Prim Care. 2003;30:63-80. iv

Leffler D.A., Lamont J.T. Treatment of Clostriduim difficile-associated disease. Gastrenterology. 2009;136:1899-1912.

Resigner E.C., Fritzche C., Krause R., et al. Diarrhea caused by primarily non-gastrointestinal infections. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;2:216-222.