Chapter 66 Acute Care of the Victim of Multiple Trauma

Epidemiology

Injury is a leading cause of death and disability in children throughout the world (Chapter 5.1). According to the World Health Organization report on child injury prevention, unintentional injuries are one of the leading causes of death in children younger than 20 yr and the leading cause of death in children between 10 and 20 yr in the world. Road traffic accidents, drowning, fire-related events, and falls rank among the top causes of death and disability in children. In Asia, injury accounts for more than 50% of deaths in children <18 yr, with drowning accounting for approximately half. In the USA, more than 12,000 children die each year secondary to unintentional injury, with motor vehicle related injuries being the leading cause.

Regionalization and Trauma Teams

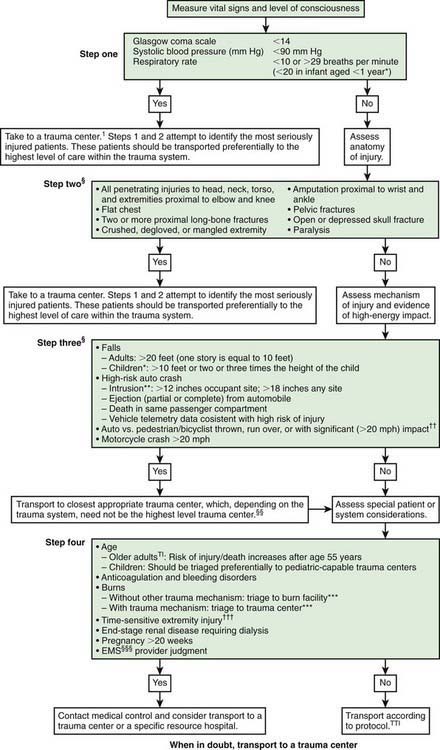

Mortality and morbidity rates have decreased in geographic regions with comprehensive, coordinated trauma systems. Treatment at designated trauma centers is associated with decreased mortality. At the scene of injury, paramedics should administer necessary advanced life support and perform triage (Fig. 66-1; Tables 66-1 and 66-2). It is usually preferable to bypass local hospitals and rapidly transport a seriously injured child directly to a pediatric trauma center (or a trauma center with pediatric commitment). Children have lower mortality rates after severe blunt trauma when they are treated in designated pediatric trauma centers or in hospitals with pediatric intensive care units.

Figure 66-1 Field triage decision scheme—United States, 2006.

§Any injury noted in Steps 2 and 3 triggers a “yes” response.

†††Injuries such as an open fracture or fracture with neurovascular compromise.

Table 66-1 CHANGES IN FIELD TRIAGE DECISION SCHEME CRITERIA FROM 1999 TO 2006 VERSION*

STEP ONE: PHYSIOLOGIC CRITERIA

STEP TWO: ANATOMIC CRITERIA

STEP THREE: MECHANISM-OF-INJURY CRITERIA

STEP FOUR: SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

* Scheme is shown in Fig. 66-1.

Modified from Sasser SM, Hunt RC, Sullivent EE, et al: Guidelines for field triage of injured patients: recommendations of the National Expert Panel on Field Triage, MMWR Recomm Rep 58(RR-1):1–35, 2009. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr5801.pdf.

Table 66-2 CHILDREN REQUIRING PEDIATRIC TRAUMA CENTER CARE

Modified from Krug SE: The acutely ill or injured child. In Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, editors: Nelson essentials of pediatrics, ed 4, Philadelphia, 2002, WB Saunders, p 96.

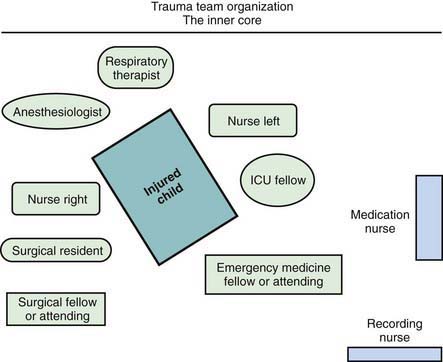

When the receiving ED is notified before the child’s arrival, the trauma team should also be mobilized in advance. Each member has defined tasks. A senior surgeon (surgical coordinator) or, sometimes initially, an emergency physician leads the team. Team compositions vary somewhat from hospital to hospital; the model used at Children’s National Medical Center (Washington, DC) is shown in Figure 66-2. Consultants, especially neurosurgeons and orthopedic surgeons, must be promptly available; the operating room staff should be alerted.

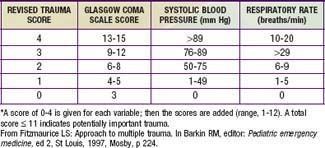

Physiologic status, anatomic locations, and/or mechanism of injury are used for field triage as well as to determine whether to activate the trauma team (see Table 66-2). More importance should be placed on physiologic compromise and less on mechanism of injury. Scoring scales such as the Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS), Injury Severity Score (ISS), Pediatric Trauma Score, and Revised Trauma Score (Table 66-3) use these parameters to predict patient outcome. The AIS and ISS are used together. First, the AIS is used to numerically score injuries—as 1 minor, 2 moderate, 3 serious, 4 severe, 5 critical, or 6 probably lethal—in each of 6 ISS body regions: head/neck, face, thorax, abdomen, extremity, and external. The ISS is the sum of the squares of the highest 3 AIS region scores.

Primary Survey

Breathing

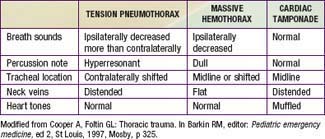

Although less common than a pulmonary contusion, tension pneumothorax and massive hemothorax are immediately life-threatening (Tables 66-4 and 66-5). Tension pneumothorax occurs when air accumulates under pressure in the pleural space. The adjacent lung is compacted, the mediastinum is pushed toward the opposite hemithorax, and the heart, great vessels, and contralateral lung are compressed or kinked (Chapter 405). Both ventilation and cardiac output are impaired. Characteristic findings include cyanosis, tachypnea, retractions, asymmetric chest rise, contralateral tracheal deviation, diminished breath sounds on the ipsilateral (more than contralateral) side, and signs of shock. Needle thoracentesis, followed by thoracostomy tube insertion, is diagnostic and lifesaving. Hemothorax results from injury to the intercostal vessels, lungs, heart, or great vessels. When ventilation is adequate, fluid resuscitation should begin before evacuation, because a large amount of blood may drain through the chest tube, resulting in shock.

Table 66-4 LIFE-THREATENING CHEST INJURIES

TENSION PNEUMOTHORAX

OPEN PNEUMOTHORAX (SUCKING CHEST WOUND)

Effect on ventilation depends on size

MAJOR FLAIL CHEST

MASSIVE HEMOTHORAX

CARDIAC TAMPONADE

Beck Triad:

Modified from Krug SE: The acutely ill or injured child. In Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, editors: Nelson essentials of pediatrics, ed 4, Philadelphia, 2002, WB Saunders, p 97.

Circulation

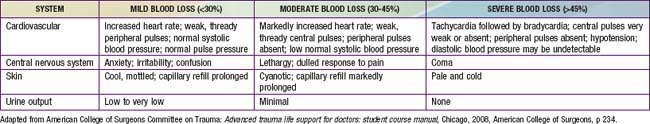

The most common type of shock in trauma is hypovolemic shock due to hemorrhage. Signs of shock include tachycardia; weak pulse; delayed capillary refill; cool, mottled, pale skin; and altered mental status (Chapter 64). Early in shock, blood pressure remains normal because of compensatory increases in heart rate and peripheral vascular resistance (Table 66-6). Some individuals can lose up to 30% of blood volume before blood pressure declines. It is important to note that 25% of blood volume equals 20 mL/kg, which is only 200 mL in a 10-kg child. Losses >40% of blood volume cause severe hypotension that, if prolonged, may become irreversible. Direct pressure should be applied to control external hemorrhage. Blind clamping of bleeding vessels, which risks damaging adjacent structures, is not advisable.

Neurologic Deficit

Head injuries account for approximately 70% of pediatric blunt trauma deaths. Primary direct cerebral injury occurs within seconds of the event and is irreversible. Secondary injury is caused by subsequent anoxia or ischemia. The goal is to minimize secondary injury by ensuring adequate oxygenation, ventilation, and perfusion, and maintaining normal intracranial pressure (ICP). A child with severe neurologic impairment—i.e., with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS; see Table 62-3) score of 8 or less—should be intubated.

Secondary Survey

During the secondary survey, the physician completes a detailed, head-to-toe physical examination.

Head Trauma

A GCS or Pediatric GCS score (see Table 62-3) should be assigned to every child with significant head trauma. This scale assesses eye opening and motor and verbal responses. In the Pediatric GCS, the verbal score is modified for age. The GCS further categorizes neurologic disability, and serial measurements identify improvement or deterioration over time. Patients with low scores 6-24 hr after injuries have poorer prognoses.

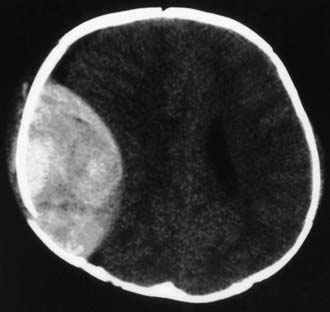

In the ED, CT scanning of the head without a contrast agent has become standard to determine the type of injury. Diffuse cerebral injury with edema is a common and serious finding on CT scan in severely brain-injured children. Focal evacuable hemorrhagic lesions (e.g., epidural hematoma) occur less commonly but may require immediate neurosurgical intervention (Fig. 66-3).

Monitoring of ICP should be strongly considered for children with severe brain injury, particularly for those with a GCS score of 8 or less and abnormal head CT findings (Chapter 63). An advantage of an intraventricular catheter over an intraparenchymal device is that cerebrospinal fluid can be drained to treat acute increases in ICP. Hypoxia, hypercarbia, hypotension, and hyperthermia must be aggressively managed to prevent secondary brain injury. Cerebral perfusion pressure should be maintained >40 mm Hg at least (although some experts recommend an even higher minimum).

Cervical Spine Trauma

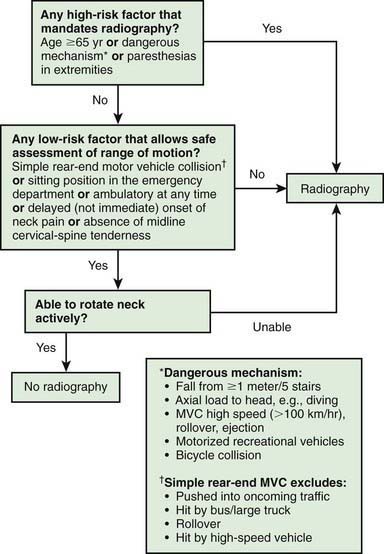

Whenever the history, physical examination, or mechanism of injury suggests a cervical spine injury, radiographs should be obtained after initial resuscitation. In adults, the Canadian C-spine rule helps identify low-risk patients who may not require radiographs (Fig. 66-4). The standard series of plain radiographs includes lateral, anteroposterior, and odontoid views. Some centers use cervical spine CT as the primary diagnostic tool, particularly in patients with abnormal GCS scores and/or significant injury mechanisms, recognizing that CT is more sensitive in detecting bony injury than plain radiographs. CT is also helpful if an odontoid fracture is suspected, because young children typically do not cooperate enough to obtain an “open-mouth” (odontoid) radiographic view. Use of cervical spine CT scan must be balanced with the knowledge that CT exposes thyroid tissue to 90-200 times the amount of radiation from plain films. MRI is indicated in a child with suspected SCIWORA.

Thoracic Trauma

Rib fractures result from significant external force. They are noted in patients with more severe injuries and are associated with a higher mortality rate. Flail chest, which is caused by multiple rib fractures, is rare in children. Indications for operative management in thoracic trauma are listed in Table 66-7. The differential diagnosis of immediately life-threatening cardio-pulmonary injuries is shown in Table 66-5.

Table 66-7 INDICATIONS FOR OPERATION IN THORACIC TRAUMA

THORACOTOMY IMMEDIATELY OR SHORTLY AFTER INJURY

DELAYED THORACOTOMY

Modified from O’Neill JA Jr: Principles of pediatric surgery, ed 2, St Louis, 2003, Mosby, p 157.

Abdominal Trauma

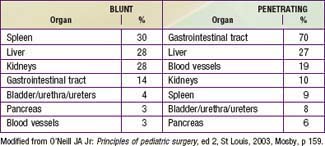

Liver and spleen contusions, hematomas, and lacerations account for the majority of intra-abdominal injuries from blunt trauma. The kidneys, pancreas, and duodenum are relatively spared because of their retroperitoneal location. Pancreatic and duodenal injuries are more common after a bicycle handlebar impact or a direct blow to the abdomen (Table 66-8).

Although a thorough examination for intra-abdominal injuries is essential, achieving it often proves difficult. Misleading findings can result from gastric distention after crying or in an uncooperative toddler. Calm reassurance, distraction, and gentle, persistent palpation help with the examination. Important findings include distention, bruises, and tenderness. Specific symptoms and signs give insight into the mechanism of injury and the potential for particular injuries. Pain in the left shoulder may signify splenic trauma. A lap belt mark across the abdomen suggests a bowel or mesentery injury. The presence of certain other injuries, such as lumbar spinal fractures and femur fractures, increases the likelihood of intra-abdominal injury. Other risks are listed in Table 66-9.

Table 66-9 PREDICTION RULE FOR IDENTIFICATION OF CHILDREN WITH INTRA-ABDOMINAL INJURIES AFTER BLUNT TORSO TRAUMA

If any one of the following is present, the patient likely has intra-abdominal injury:

* Serum aspartate aminotransferase level >200 U/L or serum alanine aminotransferase level >125 U/L.

† >5 red blood cells/high powered field.

Modified from Holmes JF, Mao A, Awasthi S, et al: Validation of a prediction rule for the identification of children with intra-abdominal injuries after blunt torso trauma, Ann Emerg Med 54:528–533, 2009.

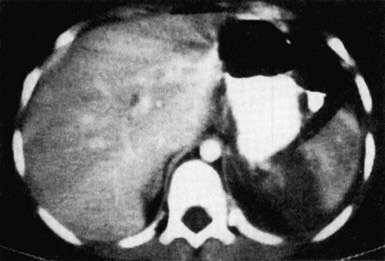

An abdominal CT scan with intravenous contrast medium enhancement rapidly identifies structural and functional abnormalities and is the preferred study in a stable child. It has excellent sensitivity and specificity for splenic (Fig. 66-5), hepatic (Fig. 66-6), and renal injuries but is not as sensitive for diaphragmatic, pancreatic, or intestinal injuries. Small amounts of free fluid or air or a mesenteric hematoma may be the only sign of an intestinal injury. Administration of an oral contrast agent is not routinely recommended for all abdominal CT scans, but it sometimes aids in identifying an intestinal, especially a duodenal, injury.

Radiologic and Laboratory Evaluation

Clinical prediction rules that combine patient history with physical exam findings have been developed to identify those at low risk of injury for whom specific radiographic and laboratory studies may not be necessary. The Canadian C-spine rule for adults is one such rule (see Fig. 66-4). In children, a clinical prediction rule for the identification of children with intra-abdominal injuries following blunt trauma has been validated. The presence of any of the risk factors in this prediction rule had a sensitivity of 95% for identifying children with intra-abdominal injury (see Table 66-9). Several clinical prediction rules have also been developed to predict traumatic brain injury following blunt head trauma. These rules, if successfully validated, may allow for more appropriate use of CT in pediatric trauma patients and may potentially reduce unnecessary radiation exposure.

American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Orthopaedics, American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Critical Care, American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Surgery, American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Transport Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine, Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North AmericaKrug SE, Tuggle DW. Management of pediatric trauma. Pediatrics. 2008;121:849-854.

American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. Advanced trauma life support for doctors: student course manual. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 2008.

Atabaki SM, Stiell IG, Bazarian JJ, et al. A clinical decision rule for cranial computed tomography in minor pediatric head trauma. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:439-445.

Borse NN, Gilchrist J, Dellinger AM, et al. CDC childhood injury report: patterns of unintentional injuries among 0–19 year olds in the United States. 2000–2006. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention, Atlanta, 2008. http://www.cdc.gov/SafeChild/ChildhoodInjuryReport/b_Summary.html.

Bracken MB: Steroids for acute spinal cord injury, Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2):CD001046, 2002.

Bratton SL, Chestnut RM, Ghajar J, et al. Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:S7-S95.

Cooper A, Fallat ME, Mooney DP, et al, editors. National trauma data bank pediatric report. Chicago: American College of Surgeons, 2007.

Davis DH, Localio AR, Stafford PW, et al. Trends in operative management of pediatric splenic injury in a regional trauma system. Pediatrics. 2005;115:89-94.

Demetriades D, Karaiskakis M, Velmahos GC, et al. Pelvic fractures in pediatric and adult trauma patients: are they different injuries? J Trauma. 2003;54:1146-1151.

Dingeman RS, Mitchell EA, Meyer EC, et al. Parent presence during complex invasive procedures and cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a systematic review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2007;120:842-854.

Dowd MD, McAneney C, Lacher M, et al. Maximizing the sensitivity and specificity of pediatric trauma team activation criteria. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:1119-1125.

Feliz A, Shultz B, McKenna C, et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic laparoscopy in pediatric abdominal trauma. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:72-77.

Frenk J, Gomez-Dantes O. Whole-body CT in multiple trauma. Lancet. 2009;373:1408-1409.

Holmes JF, Gladman A, Chang CH. Performance of abdominal ultrasonography in pediatric blunt trauma patients: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:1588-1594.

Holmes JF, Mao A, Awasthi S, et al. Validation of a prediction rule for the identification of children with intra-abdominal injuries after blunt torso trauma. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:528-533.

Jansen JO, Thomas R, Louden MA, et al. Damage control resuscitation for patients with major trauma. BMJ. 2009;338:1436-1440.

Jansen JO, Yule SR, Louden MA. Investigation of blunt abdominal trauma. BMJ. 2008;36:938-942.

Jimenez RR, DeGuzman MA, Shiran S, et al. CT versus plain radiographs for evaluation of c-spine injury in young children: do benefits outweigh risks? Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38:635-644.

Karam O, Sanchez O, Chardot C, et al. Blunt abdominal trauma in children: a score to predict the absence of organ injury. J Pediatr. 2009;154:912-917.

Kristoffersen KW, Mooney DP. Long-term outcome of nonoperative pediatric splenic injury management. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:1038-1042.

Linnan M, Anh LV, Cuong PV, et al. Child mortality and injury in Asia: survey results and evidence. Innocenti working paper 2007–06, special series on child injury no. 3. UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, Florence, 2007.

Mathen R, Inaba K, Munera F, et al. Prospective evaluation of multislice computed tomography versus plain radiographic cervical spine clearance in trauma patients. J Trauma. 2007;62:1427-1431.

Pracht EE, Tepas JJ, Langland-Orban B, et al. Do pediatric patients with trauma in Florida have reduced mortality rates when treated in designated trauma centers? J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:212-221.

Sammour T, Kahokehr A, Caldwell S, et al. Venous glucose and arterial lactate as biochemical predictors of mortality in clinically severely injured trauma patients: a comparison with ISS and TRISS. Injury. 2009;40:104-108.

Sasser SM, Hunt RC, Sullivent EE, et al. Guidelines for field triage of injured patients: recommendations of the National Expert Panel on Field Triage. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009;58(RR-1):1-35. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr5801.pdf.

Stiell IG, Clement CM, McKnight RD, et al. The Canadian C-spine rule versus the NEXUS low-risk criteria in patients with trauma. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2510-2518.

Valentino M, Serra C, Pavlica P, et al. Blunt abdominal trauma: diagnostic performance of contrast-enhanced US in children—initial experience. Radiology. 2008;246:903-909.

Wakai A, Roberts IG, Schierhout G: Mannitol for acute traumatic brain injury, Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1):CD001049, 2007.

Wolf SJ, Bebarta VS, Bonnett CJ, et al. Blast injuries. Lancet. 2009;376:405-414.

Zealley IA, Chakraverty S. The role of interventional radiology in trauma. BMJ. 2010;340:356-360.

66.1 Care of Abrasions and Minor Lacerations

Lacerations and Cuts

Treatment

Most lacerations seen in the pediatric ED or office should be closed primarily. Contraindications to primary closure (e.g., certain bite wounds) do exist (Chapter 705). Although it is commonly accepted that the time from injury to repair should be as brief as possible to minimize the risk of infection, there is no universally accepted guideline as to what length of time is too long for primary wound closure. Also, this length of time varies for different types of lacerations. A prudent recommendation is that higher-risk wounds should be closed within 6 hr at most after the injury but that some low-risk wounds (e.g., clean facial lacerations) may be closed as late as 12-24 hr.

For most routine lacerations evaluated in the ED or office that are repaired early and carefully, prophylactic systemic antibiotics are unnecessary because they do not decrease the rate of infection. Antibiotic prophylaxis is or may be indicated for human and many animal bites, for open fractures and joints, and for grossly contaminated wounds, as well as for wounds in patients who are immunosuppressed or have prosthetic devices. Tetanus prophylaxis should be administered, if indicated, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines (Chapter 203).

Abrasions

Treatment

All abrasions should be cleansed thoroughly, and any debris or foreign material removed. If debris is not removed, abnormal skin pigmentation, known as post-traumatic tattooing, can occur and can be difficult to treat. A nonadherent occlusive dressing or a topical antibiotic and conventional dressing should be applied. Tetanus prophylaxis should be administered, if indicated (Chapter 203). Large and/or deep abrasions that have not healed in a few weeks require consultation with a plastic surgeon for more advanced care.

Brown DJ, Jaffe JE, Henson JK. Advanced laceration management. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2007;25:83-99.

Chatterjee JS. A critical review of irrigation techniques in acute wounds. Int Wound J. 2005;2:258-265.

Cummings P, Del Beccaro MA. Antibiotics to prevent infection of simple wounds: a meta-analysis of randomized studies. Am J Emerg Med. 1995;13:396-400.

Field FK, Kerstein MD. Overview of wound healing in a moist environment. Am J Surg. 1994;167(Suppl 1A):2S-6S.

Hollander JE, Singer AJ, Valentine SM, et al. Risk factors for infection in patients with traumatic lacerations. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:716-720.

Lammers RL, Hudson DL, Seaman ME. Prediction of traumatic wound infection with a neural network-derived decision model. Am J Emerg Med. 2003;21:1-7.

Nakamura Y, Daya M. Use of appropriate antimicrobials in wound management. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2007;25:159-176.

Singer AJ, Dagum AB. Current management of acute cutaneous wounds. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1037-1046.

Singer AJ, Hollander JE, Quinn JV. Evaluation and management of traumatic lacerations. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1142-1148.

Singer AJ, Thode HC, Hollander JE. National trends in ED lacerations between 1992 and 2002. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24:183-188.

Wackett A, Singer AJ. The role of topical skin adhesives in wound repair. Emerg Med. 2009;41:31-35.