Chapter 335 Acute Appendicitis

Diagnostic Studies

Laboratory Findings

A complete blood count with differential and urinalysis are commonly obtained.

The Pediatric Appendicitis score combines history, physical, and laboratory data to assist in the diagnosis (Table 335-1). Scores of ≤2 suggest a very low likelihood of appendicitis, while scores ≥8 are highly associated with appendicitis. Scores between 3 and 7 warrant further diagnostic studies. Nonetheless, no scoring system is perfectly sensitive or specific.

| FEATURE | SCORE |

|---|---|

| Fever >38°C | 1 |

| Anorexia | 1 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 1 |

| Cough/percussion/hopping tenderness | 2 |

| Right lower quadrant tenderness | 2 |

| Migration of pain | 1 |

| Leukocytosis >10,000 (109/L) | 1 |

| Polymorphonuclear-neutrophilia >7,500 (109/L) | 1 |

| Total | 10 |

From Acheson J, Banerjee J: Management of suspected appendicitis in children, Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 95:9–13, 2010.

Radiologic Studies

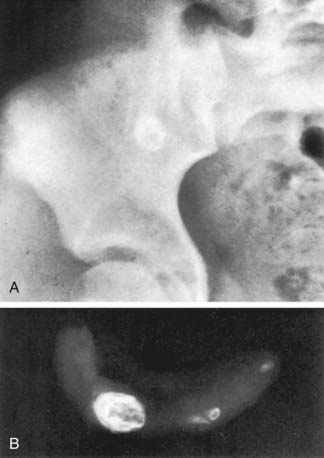

Plain Films

Plain abdominal x-rays can demonstrate several findings in acute appendicitis, including sentinel loops of bowel and localized ileus, scoliosis from psoas muscle spasm, a colonic air-fluid level above the right iliac fossa (colon cutoff sign), or a fecalith (5-10% of cases), but they have a low sensitivity for appendicitis and are not generally recommended (Fig. 335-1). Plain films are most helpful in evaluating complicated cases in which small bowel obstruction or free air is suspected.

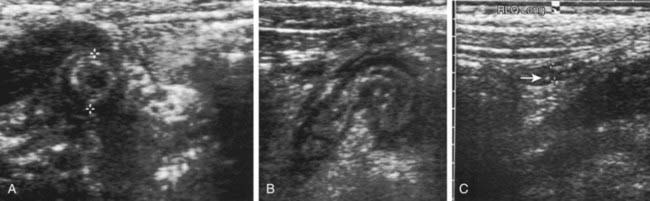

Ultrasound

Ultrasound (US) is often used in the evaluation of acute appendicitis and has demonstrated >90% sensitivity and specificity in pediatric centers experienced with the technique. Graded abdominal compression is used to displace the cecum and ascending colon and identify the appendix, which has a typical target appearance (Fig. 335-2). The ultrasound criteria for appendicitis include wall thickness ≥6 mm, luminal distention, lack of compressibility, a complex mass in the RLQ, or a fecalith. The visualized appendix usually coincides with the site of localized pain and tenderness. Findings that suggest advanced appendicitis on ultrasound include asymmetric wall thickening, abscess formation, associated free intraperitoneal fluid, surrounding tissue edema, and decreased local tenderness to compression.

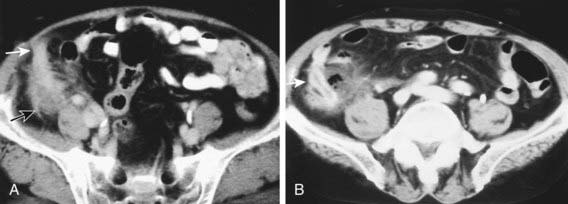

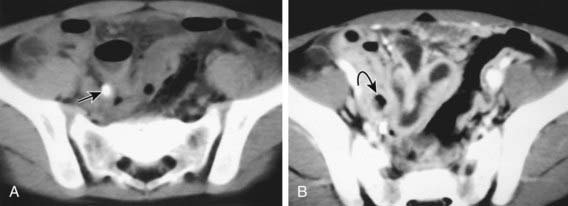

CT Scan

CT scan has been the gold standard imaging study for evaluating children with suspected appendicitis. CT examination can be performed in many ways, including standard CT scan, helical CT scan, with or without oral and intravenous contrast, examination of both the abdomen and pelvis or pelvis alone, focused appendiceal CT scan, and focused appendiceal CT scan with rectal contrast. All of these techniques have demonstrated >95% sensitivity and specificity for acute appendicitis. Findings on CT scan consistent with appendicitis include a distended thick-walled appendix, inflammatory streaking of surrounding mesenteric fat, or a pericecal phlegmon or abscess (Figs. 335-3 and 335-4).

Diagnostic Approach

The diagnostic challenges are many, including the rapid escalation of appendicitis from subtle malaise to perforation (often within 36-48 hr), variable abilities of medical centers and experience among clinicians, and fear of malpractice suits for missed diagnosis. Several reports have described clinical scoring systems and computer-assisted decision-making models incorporating specific elements of the history, physical examination, and laboratory studies designed to improve diagnostic accuracy in acute appendicitis (see Table 335-1). To date, none has demonstrated improved accuracy over experienced clinical judgment.

Acheson J, Banerjee J. Management of suspected appendicitis in children. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2010;95:9-13.

Becker T, Kharbanda A, Bachur R. Atypical clinical features of pediatric appendicitis. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:124-129.

Bhatt M, Joseph L, Ducharme FM, et al. Prospective validation of the pediatric appendicitis score in a Canadian pediatric emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:591-596.

Bundy DG, Byerley JS, Liles EA, et al. Does this child have appendicitis? JAMA. 2007;298:438-451.

Dixon AK, Watson CJ. Imaging in patients with acute abdominal pain. BMJ. 2009;339:1-2.

Fisher M, Meates-Dennis M. Is interval appendectomy necessary after successful conservative treatment of appendiceal mass in children? Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:631-632.

Frisch M, Pedersen BV, Andersson RE. Appendicitis, mesenteric, lymphadenitis, and subsequent risk of ulcerative colitis: cohort studies in Sweden and Denmark. BMJ. 2009;338:808-811.

Goldin AB, Sawin RS, Garrison MM, et al. Aminoglycoside-based triple-antibiotic therapy versus monotherapy for children with ruptured appendicitis. Pediatrics. 2007;119:905-911.

Goldman RD, Carter S, Stephens D, et al. Prospective validation of the pediatric appendicitis score. J Pediatr. 2008;153(2):278-282.

Grimes C, Chin D, Bailey C, et al. Appendiceal faecaliths are associated with right iliac fossa pain. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010;92:61-64.

Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. The kid’s inpatient database. (website) www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/kidoverview.jsp Accessed May 7, 2010

Henry MCW, Gollin G, Islam S, et al. Matched analysis of nonoperative management vs immediate appendectomy for perforated appendicitis. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:19-24.

Henry MCW, Walker A, Silverman BL, et al. Risk factors for the development of abdominal abscess following operation for perforated appendicitis in children. Arch Surg. 2007;142:236-241.

Ingraham AM, Cohen ME, Bilimoria KY, et al. Effect of delay to operation on outcomes in adults with acute appendicitis. Arch Surg. 2010;145(9):886-892.

Keckler SJ, Tsao K, Sharp SW, et al. Resource utilization and outcomes from percutaneous drainage and interval appendectomy for perforated appendicitis with abscess. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:977-980.

Kwok MY, Kim MK, Gorelick MH. Evidence-based approach to the diagnosis of appendicitis in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2004;20:690-698.

Laméris W, van Randen A, Woulter H, et al. Imaging strategies for detection of urgent conditions in patients with acute abdominal pain: diagnostic accuracy study. BMJ. 2009;339:29-33.

Morrow SE, Newman KD. Current management of appendicitis. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2007;16:34-40.

Solomkin JS, Mazuski JE, Bradley JS, et al. Diagnosis and management of complicated intra-abdominal infection in adults and children: guidelines by the Surgical Infection Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:133-164.

Wan MJ, Krahn M, Ungar WJ, et al. Acute appendicitis in young children: cost-effectiveness of US versus CT in diagnosis—a Markov decision analytic model. Radiology. 2009;250(2):378-386.

Williams RF, Blakely ML, Fischer PE, et al. Diagnosing ruptured appendicitis preoperatively in pediatric patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208(5):819-825.

Zilbert NR, Stamell EF, Ezon I, et al. Management and outcomes for children with acute appendicitis differ by hospital type: areas for improvement at public hospitals. Clin Pediatr. 2009;48(5):499-504.