Acute and Chronic Infectious Hepatitis

Lisa M. Yerian

Laura W. Lamps

Introduction

A wide variety of infectious agents can involve the liver. The most common are the “hepatotropic” viruses—those that preferentially involve the liver—including hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E. Many other viruses, such as cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), may produce hepatic injury as part of systemic infection. Although some infectious agents produce characteristic morphologic patterns of injury, in many cases the findings are relatively nonspecific. Therefore, proper interpretation of the liver biopsy requires adequate clinical information, including the patient’s immunologic status, travel history, clinical signs and symptoms, medications used, and serologic test results.

Viral Hepatitis

Viral hepatitis is defined by the presence of hepatocyte necrosis and inflammation resulting from a viral infection, which leads to a characteristic constellation of clinical and morphologic features. Most cases are caused by one of four well-known hepatotropic viruses: hepatitis A (HAV), B (HBV), C (HCV), and E (HEV); HBV infection may be further complicated by coinfection, or superinfection, with hepatitis D virus (HDV). Although other viruses, such as CMV and EBV, can cause hepatic injury and inflammation as part of a systemic illness, the hepatitis in those cases is often overshadowed by the clinical manifestations of involvement of other organ systems. Other, unidentified types of viral hepatitis may also exist, based on the rare occurrence of posttransfusion hepatitis despite adequate screening of blood donors for known infectious agents.

Viral hepatitis is divided into acute and chronic forms, based primarily on clinical evidence of chronicity. The term chronic hepatitis is used when there is evidence of persistent hepatic necrosis and inflammation. Traditionally, particularly for HBV-infected patients, chronic hepatitis has been defined clinically by the presence of aminotransferase elevations lasting at least 6 months. Histologically, however, chronic hepatitis refers to an ongoing necroinflammatory process that affects hepatocytes and is associated with portal-based inflammation and fibrosis.

Clinical Features

Acute Viral Hepatitis

Acute viral hepatitis is often asymptomatic, and in many patients, it is recognized only in retrospect after serologic tests reveal evidence of prior infection. In symptomatic patients, presenting symptoms often are only mild and nonspecific and include malaise, fatigue, low-grade fever, and flulike complaints. Asymptomatic or mild acute viral hepatitis is more common in children; adults are more likely to be symptomatic.

Symptomatic acute viral hepatitis is usually preceded by a prodrome phase that lasts from a few days to several weeks and is characterized by nonspecific symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, myalgia, anorexia, and malaise. Once jaundice develops, constitutional symptoms typically begin to wane. Physical examination is often notable only for jaundice and hepatomegaly. In addition, the liver may be tender to palpation. Serum aminotransferases, which are the key indicators of hepatocellular injury, are commonly elevated 10-fold above normal and often exceed 1000 U/L. In contrast, alkaline phosphatase is typically only mildly elevated; conjugated hyperbilirubinemia is present in some, but not all, patients. In most cases, full recovery occurs within a few weeks. In some, low-grade symptoms or signs persist for months. The treatment of acute viral hepatitis is generally supportive.

In a few cases of acute viral hepatitis (<1%), fulminant hepatic failure develops, characterized by the rapid development of liver decompensation. Although acute liver failure may result from a variety of other causes, including exposure to drugs or toxins, autoimmune liver disease, or ischemia, 12% of cases in the United States are caused by acute viral hepatitis.1 The clinical course of acute hepatic failure is characterized by coagulopathy, encephalopathy, and a high mortality rate in patients who do not undergo liver transplantation. For both acute HAV and acute HEV infection, patients with a background of chronic liver disease have a higher risk of a poor outcome.

Chronic Viral Hepatitis

As in acute hepatitis, patients with chronic hepatitis have a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations that range from asymptomatic to symptomatic decompensated cirrhosis. Many patients are asymptomatic or have only mild, nonspecific complaints, such as fatigue. Findings on physical examination are typically few but include hepatomegaly and other stigmata of chronic liver disease, such as palmar erythema. Ascites and esophageal or cutaneous varices may also develop in patients with advanced cirrhosis. Serum aminotransferase levels fluctuate but are usually chronically elevated in the 2- to 10-fold range, although a substantial number of patients with mild chronic hepatitis C have persistently normal aminotransferase levels. Alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin levels are usually normal to mildly elevated unless hepatic decompensation has occurred, in which case high levels may be observed.

Hepatitis Viruses

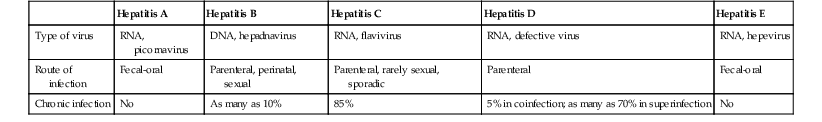

Hepatitis A

HAV is a small, 27-nm, nonenveloped, single-stranded RNA virus in the picornavirus family (Table 46.1). Although HAV remains the most common cause of acute viral hepatitis in the world, infection rates in the United States and other countries have declined progressively with increased use of hepatitis A vaccination.2,3 Infection rates are higher in areas of poor sanitation or overcrowding, such as in developing countries and in institutions for people with developmental disabilities. Outbreaks in day care centers and residential institutions also occur, although proper hand washing and sewage disposal help reduce spread of the virus.2

Table 46.1

Viral Hepatitis

| Hepatitis A | Hepatitis B | Hepatitis C | Hepatitis D | Hepatitis E | |

| Type of virus | RNA, picornavirus | DNA, hepadnavirus | RNA, flavivirus | RNA, defective virus | RNA, hepevirus |

| Route of infection | Fecal-oral | Parenteral, perinatal, sexual | Parenteral, rarely sexual, sporadic | Parenteral | Fecal-oral |

| Chronic infection | No | As many as 10% | 85% | 5% in coinfection; as many as 70% in superinfection | No |

The major route of transmission of HAV is oral ingestion of fecally excreted virus through person-to-person contact or ingestion of contaminated food or water. Approximately 50% of patients have no identifiable source of infection. During infection, the virus is transported across intestinal epithelium and travels to the liver through the portal system, where it is taken up by hepatocytes. The virus replicates in hepatocytes and is then excreted into bile and shed into stool. HAV is not directly cytopathic; hepatocyte injury occurs via a cell-mediated immune mechanism. The virus is resistant to bile lysis and can be excreted into the intestine and feces or released into the systemic circulation. There are four genotypes, but only one serotype, of the hepatitis A virus. The mean incubation period for HAV is 28 days (range, 15 to 40 days). The diagnosis is usually established by detection of immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies to HAV, which are usually detectable in serum within 1 to 2 weeks after exposure and may persist for 3 to 6 months.4 Anti-IgG antibody to HAV is detectable 5 to 6 weeks after exposure and persists for decades.

The clinical symptoms of HAV infection are usually mild, and many patients are asymptomatic. The most important factor that determines severity of disease is patient age: only 30% of children are symptomatic, compared with 70% of adults. The overall case-fatality rate resulting from fulminant hepatitis A is low (0.2%), but HAV infection may produce substantial morbidity in elderly patients and in those with preexisting chronic liver disease.2 The onset of classic HAV infection is typically abrupt, characterized by the presence of fever, headache, malaise, and nonspecific gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, followed by jaundice a week later. Symptoms usually resolve within 8 weeks. A relapsing variant of hepatitis A has been recognized, and in as many as 10% of patients, the disease has a prolonged cholestatic course. However, chronic disease never occurs as a result of HAV virus infection.

Hepatitis B

HBV contains a partially double-stranded, circular DNA genome and is a member of the hepadnavirus family of viruses. The complete viral particle, referred to as the Dane particle, consists of an outer envelope that surrounds a core of DNA, the hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg), the hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), and DNA-dependent polymerase. The outer envelope contains the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). Both complete and incomplete viral particles circulate in the blood of infected patients. In fact, HBsAg can circulate in large quantities as incomplete tubular or spherical structures that lack DNA. Viral DNA may become incorporated into host DNA within infected hepatocytes, particularly in young patients, and these patients are at high risk for subsequent development of hepatocellular carcinoma. The viral antigen load and subsequent antibody response may be used as serologic markers to evaluate the time course of infection (Table 46.2).

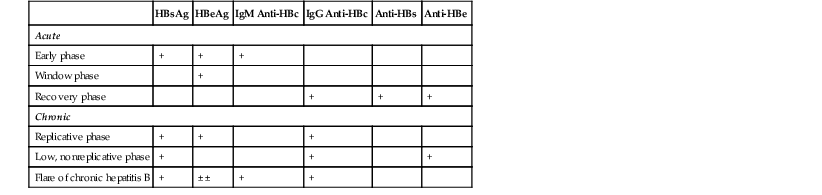

Table 46.2

Serologic Markers for Hepatitis B Infection in Acute and Chronic Disease*

| HBsAg | HBeAg | IgM Anti-HBc | IgG Anti-HBc | Anti-HBs | Anti-HBe | |

| Acute | ||||||

| Early phase | + | + | + | |||

| Window phase | + | |||||

| Recovery phase | + | + | + | |||

| Chronic | ||||||

| Replicative phase | + | + | + | |||

| Low, nonreplicative phase | + | + | + | |||

| Flare of chronic hepatitis B | + | ± ± | + | + | ||

* Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) is present in the serum in both acute and chronic hepatitis and indicates an infectious state.

Hepatitis B envelope antigen (HBeAg) is present in the serum in acute and chronic hepatitis and indicates a highly infectious state.

Hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs) is present in the serum in the recovery phase and in immunity (i.e., vaccination).

Hepatitis B envelope antibody (anti-HBe) is present in the serum in the recovery phase.

Total hepatitis B core antibody (Immunoglobulin [IG] G anti-HBc) is present in the serum in both acute and chronic hepatitis and indicates previous or ongoing infection.

IgM antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (IgM anti-HBc) is present in the serum in acute hepatitis (as much as 6 months after infection).

Data from Lok ASF. Serologic diagnosis of hepatitis B virus infection. UpToDate (last updated March 6, 2013). Available at http://www.uptodate.com/contents/serologic-diagnosis-of-hepatitis-b-virus-infection?source=search_result&search=hepatitis+b+diagnosis&selectedTitle=1%7E150. Accessed November 21, 2013.

HBV is transmitted through exposure to infected body fluids and by intravenous drug use, sexual contact, and occupational activity. Perinatal transmission is common (90%) if the mother is HBeAg positive, which is indicative of highly infectious disease and active viral replication, but less common (10%) if the mother is HBsAg positive. In high-prevalence areas, HBV infection is often acquired by maternal–neonatal transmission, which results in a high rate of chronic disease. In areas of low prevalence, hepatitis B is mainly a disease of young adults, who acquire the virus through parenteral or sexual exposure. Posttransfusion hepatitis B is virtually nonexistent in the United States because of routine screening of blood donors.

HBV is responsible for as many as 40% of cases of acute hepatitis in the United States. Clinical symptoms of acute hepatitis develop in approximately 30% of infected adults but in only 10% of children younger than 4 years of age; they typically appear 45 to 180 days after exposure.5 Fulminant hepatic failure occurs in approximately 1% of cases of acute hepatitis B. Acute liver failure may also occur in patients with chronic hepatitis B in which mutations are present in the precore, or core promoter, regions of the viral DNA.5 Chronic hepatitis develops in fewer than 10% of adult patients but in as many as 90% of infected infants. The rate of progression to cirrhosis depends on the presence or absence of active viral replication and the severity of liver damage (evident histologically). For instance, 50% of patients with chronic hepatitis B and marked activity progress to cirrhosis within 4 years. The annual probability that cirrhosis will develop is estimated to be 12% for patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatocellular carcinoma develops in 2.4% of patients with chronic hepatitis B annually, as well as in 0.5% of patients with chronic hepatitis without cirrhosis.5

Hepatitis C

HCV is a spherical, enveloped, single-stranded RNA virus that measures approximately 50 mm in diameter. It is classified as a separate genus within the Flaviviridae family. The genome for HCV is characterized by sequence heterogeneity, which is a result of pressure from the host immune system. This feature allows the virus to escape immune surveillance and establish chronic infection. Six major genotypes are recognized: the most common are 1a, 1b, 2a, and 2b.

HCV is transmitted primarily by parenteral exposure. Intravenous drug users and patients with hemophilia have a particularly high prevalence rate of infection. Intranasal cocaine use and sexual promiscuity are independent risk factors for acquisition of infection,6 although the risk associated with sexual transmission of HCV is low compared with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or HBV.7 Although this virus was initially identified as the etiologic agent of transfusion-acquired “non-A, non-B” hepatitis, posttransfusion hepatitis C has decreased dramatically because of widespread implementation of donor screening. The risk of infection with HCV is now estimated to be 0.01% to 0.001% for each unit of blood transfused.7 Rates of perinatal transmission are estimated to be lower than 5%.

HCV accounts for approximately 15% of cases of acute hepatitis in the United States,2 but acute infection is usually asymptomatic and only rarely recognized clinically. The incidence of acute HCV infection peaked in the late 1980s and early 1990s and has been steadily declining since, to less than 20 acute infections per 100,000 individuals per year .8 The incubation period of hepatitis C is 7 weeks, with a range of 2 to 30 weeks based on studies of transfusion-acquired cases.9 Fulminant hepatitis C is rare. Chronic infection is a far more common problem, occurring in at least 85% of infected patients. Most patients with chronic hepatitis C have few or no symptoms. Serum aminotransferase levels are often only mildly elevated, fluctuating from 1.5 to 10 times the upper limit of normal, and as many as 30% of patients have normal aminotransferase levels.10 Factors associated with progressive disease include patient age older than 40 years at the time of exposure, immunodeficiency, a high degree of viral heterogeneity, genotype 1, male gender, and long duration of infection.8,10 Alcohol is known to potentiate viral replication and is associated with greater activity and fibrosis.11 Although hepatic steatosis has been correlated with increased progression of fibrosis, it is unclear whether this result is confounded by associated metabolic abnormalities.8 Diagnostic tests currently in use include polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for detection of circulating viral RNA and a third-generation enzyme immunoassay for detection of anti-HCV antibodies.

The natural history of HCV infection has proved challenging to study, in part because of the difficulty in determining onset of infection. In most patients, the disease is believed to have an indolent course for as long as 2 decades; cirrhosis has developed in 20% to 40% of patients in studies with at least 10 to 20 years of follow-up.8,12 Currently, chronic hepatitis C is the reason for 30% of liver transplantations performed in the United States. The risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV-related cirrhosis is estimated to be approximately 1% to 4% per year.10

Occult HCV infection is a more recently recognized entity that has two distinct types of clinical presentation. The first type occurs in patients with persistently elevated liver function test results but negative serologic test results for HCV.13,14 The second type is seen in patients with positive anti-HCV serology, absence of serum HCV-RNA, and normal liver function test results. In an initial study of 100 patients with elevated liver function test results and negative HCV serology, more than half were found to have HCV-RNA in their livers by reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR and in situ hybridization.14 Preliminary studies have demonstrated that patients with occult HCV infection have higher triglyceride and cholesterol levels, decreased necroinflammatory scores and fibrosis, and fewer HCV-infected hepatocytes (by in situ hybridization).13,15

Patients with hepatitis C may also be coinfected with HIV, especially high-risk individuals such as intravenous drug users. As many as 25% of HIV-infected individuals in North America are also infected with HCV.16,17 Effective use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has decreased the morbidity and mortality rates from HIV infection and increased the risk of death from other causes, such as hepatitis C liver disease.

HCV infection is associated with a variety of extrahepatic manifestations and is now thought to be responsible for most cases of essential mixed cryoglobulinemia.18 HCV is also strongly associated with porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) in the United States, although there is marked geographic variation in the prevalence rate of HCV in patients with PCT.19 Homozygosity for the Cys282Tyr mutation in the hemochromatosis gene and HCV infection are significant risk factors for the expression of PCT, with heavy alcohol use often being a contributing factor.20 The characteristic birefringent, yellow-brown, needle-shaped crystals described in PCT are rarely found in routinely processed liver biopsy specimens because they are highly soluble in water.

Hepatitis D

HDV, also known as the delta agent, is a small, defective RNA virus that requires HBsAg for packaging and transmission to cause infection and tissue injury. It is spread by mechanisms similar to those that transmit HBV, and it may manifest as a coinfection or superinfection with HBV. HDV infection can cause acute or chronic hepatitis. Coinfection or superinfection can cause fulminant hepatic failure. HDV infection should be suspected in all patients with hepatitis B in whom severe exacerbation of disease activity develops. The finding of anti-HDV antibody in a patient who is seropositive for HBsAg is diagnostic. Three genotypes are recognized.21 In general, the histologic features of HDV infection are not distinctive, but HDV is associated with more pronounced necroinflammatory activity and more rapid progression than is seen in patients with isolated HBV infection. Microvesicular fat may be present in severe cases.22 Delta antigen can be demonstrated by immunohistochemical means and is located primarily in hepatocyte nuclei.22

Hepatitis E

HEV is a small, nonenveloped, single-stranded RNA virus that was originally classified in the family Caliciviridae but subsequently placed in the family Hepeviridae.23 Hepatitis E is endemic in parts of Africa, India, southeast and central Asia, and Mexico. Fecal-oral transmission usually occurs through ingestion of contaminated water, although sporadic cases associated with animal contact or consumption have been documented.23 HEV causes a mild form of acute hepatitis, which lasts 1 to 4 weeks in most patients but is particularly severe in pregnant women, in whom it is associated with an increased risk of acute liver failure and a mortality rate of as much as 25%. The incubation period is 4 to 5 weeks. Reports of histopathology indicate multiple patterns, ranging from a typical acute hepatitis morphologic picture, to a cholestatic form with canalicular bile plugs and cholestatic pseudorosettes, and, in a small series of patients with autochthonous infection, a severe form showing mixed portal and acinar inflammation with severe interface hepatitis and cholangiolitis.25 Massive or submassive necrosis may occur in severe cases. Although HEV infection has been considered a self-limited disease, persistent infection has been documented in immunocompromised patients and in patients with HIV infection.26 Serologic assays for anti-HEV IgG and IgM, and RT-PCR assay are used to confirm the clinical diagnosis.24

Other Hepatitis Viruses

GB virus type C (GBV-C), also known as the hepatitis G virus, was discovered in 1995 and is a flavivirus in the same family as HCV. This virus has been detected in 1.7% of the population and can be transmitted parenterally and by vertical transmission.27 Viral replication occurs predominantly in lymphocytes, although the virus is also detectable in hepatocytes.

The single-stranded, nonenveloped DNA virus known as TT virus was originally suspected to cause transfusion-associated hepatitis, but later it was found in more than 90% of Japanese blood donors, casting doubt on its role in causing disease.28 Similarly, the related single-stranded circular DNA virus, the SEN virus, has also been found in patients with transfusion-associated hepatitis, although direct causality has not been established.29

Acute Hepatitis

Pathologic Features

Table 46.3 summarizes the pathologic features of acute and chronic hepatitis.

Table 46.3

Histopathologic Features of Acute and Chronic Hepatitis

| Acute | Chronic |

| Predominantly lobular inflammation | Predominantly portal tract inflammation |

| Lobular regeneration and disarray | Lobular acidophil bodies |

| Hepatocyte swelling | Mononuclear inflammatory cells, occasional plasma cells |

| Kupffer cell aggregates | Portal-based lymphoid aggregates and lymphoid follicle formation |

| Apoptotic bodies (acidophils) | Progressive fibrosis with eventual cirrhosis |

| Mononuclear inflammatory cells, with occasional eosinophils and neutrophils | Interface hepatitis |

| Canalicular cholestasis | Bile ductular proliferation |

| Hepatocyte dropout, necrosis |

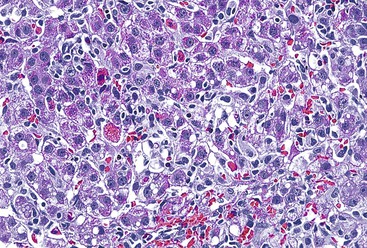

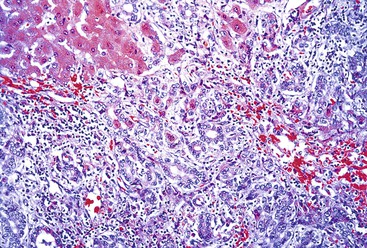

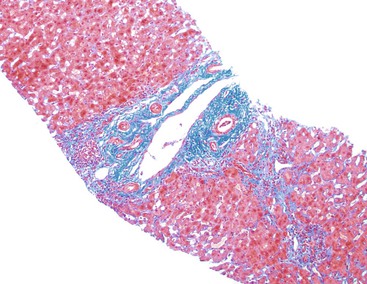

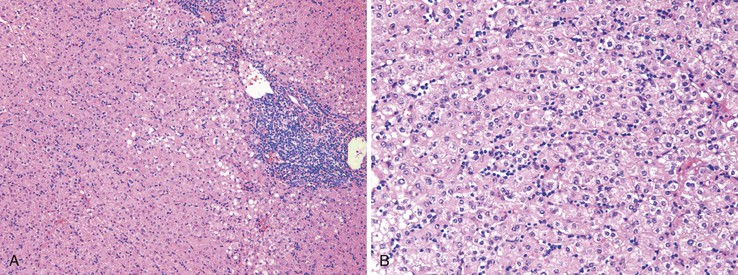

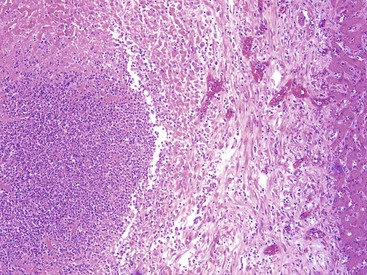

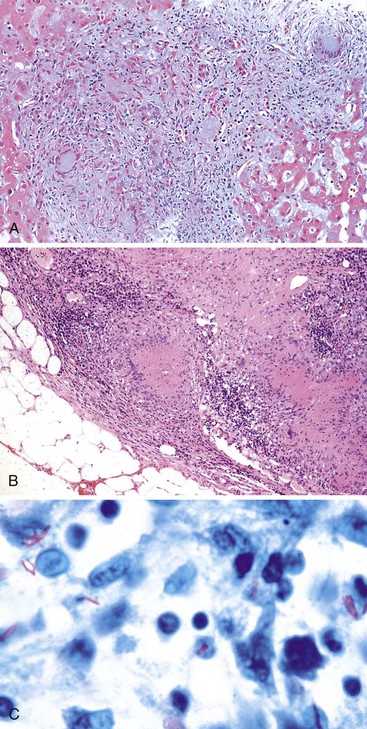

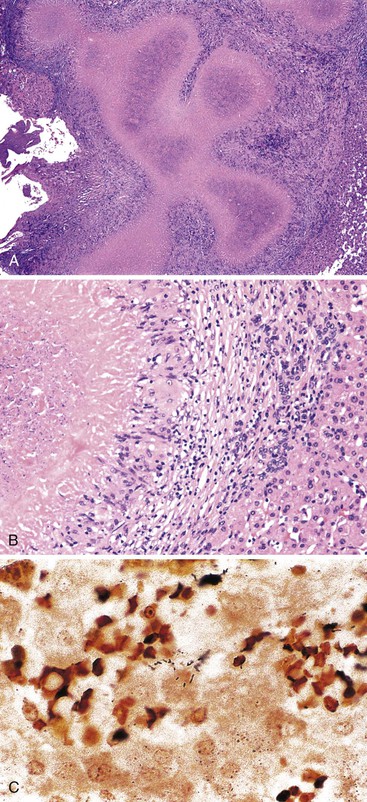

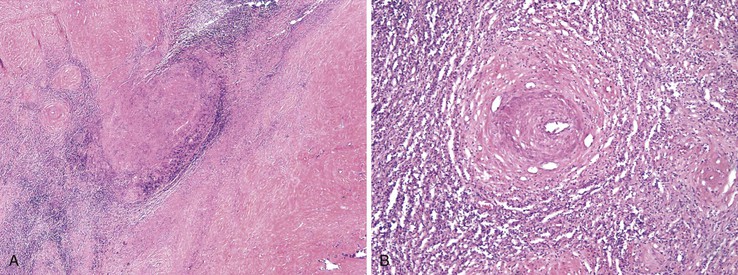

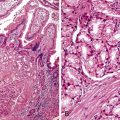

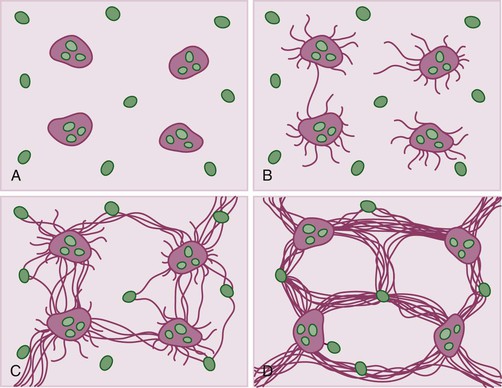

Patients with acute viral hepatitis seldom undergo liver biopsy because the diagnosis is usually easily established by noninvasive serologic tests. On low-power microscopic examination, acute cases show a necroinflammatory process that involves all areas of the hepatic lobules and hence is not confined to the portal tracts. The combination of hepatocyte injury, loss, and regeneration with the presence of a mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate leads to a pattern termed lobular disarray, which reflects a disruption of the normal orderly architecture of the liver cell plates (Fig. 46.1).

Lobular hepatocellular changes include hepatocyte swelling, in which the affected cells are pale stained and show irregular, wispy cytoplasm and clumping of cytoplasm around the nucleus. Other forms of hepatocyte necrosis occur as well (described later). Swollen hepatocytes often undergo “lytic necrosis,” marked by the presence of small foci of stromal collapse associated with small clusters of mononuclear inflammatory cells. In addition, hepatocytes may undergo acidophilic changes, in which the cell becomes shrunken, angular, and hypereosinophilic, and contains a densely stained pyknotic nucleus. This type of necrosis leads to acidophilic bodies (apoptotic bodies), which are small, mummified, rounded cell remnants that may also extrude fragments of degenerated nuclei. Apoptotic bodies may be phagocytosed by Kupffer cells, resulting in Kupffer cell hyperplasia. Individual or small clusters of necrotic hepatocytes are collectively referred to as “spotty” hepatocyte necrosis. Regeneration of hepatocytes contributes to the “busy” appearance of the hepatic lobules, because the liver cell plates are typically irregular and thickened. Nonspecific steatosis may also occur in cases of acute hepatitis.

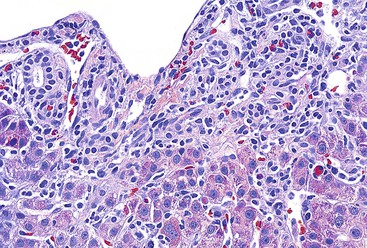

Canalicular cholestasis is usually not a prominent feature in cases of acute viral hepatitis. However, cholestasis may occasionally be so prominent that the histologic changes mimic those of biliary obstruction. In this variant, termed acute cholestatic hepatitis, one sees marked lobular inflammation and hepatocanalicular cholestasis. There may also be bile accumulation within the lumina of bile ducts and ductules. The finding of a prominent bile ductular reaction associated with neutrophils (termed cholangiolitis) in the portal tracts may contribute to confusion with biliary obstruction. Marked hepatocyte swelling and regenerating cholestatic rosettes (hepatocyte “pseudoglands”) may be present in the hepatic lobules (Fig. 46.2). Typically, cases of acute cholestatic hepatitis have a more prolonged clinical course.

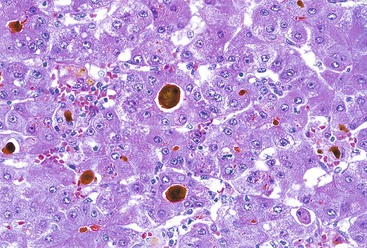

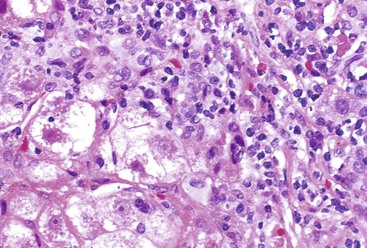

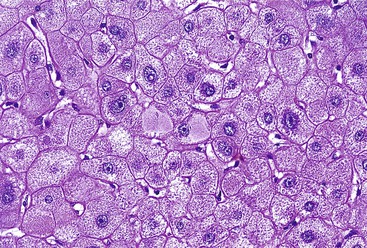

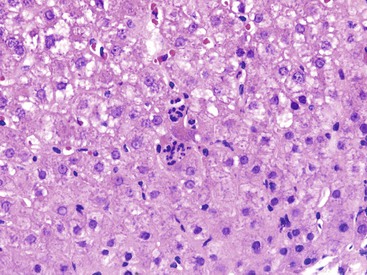

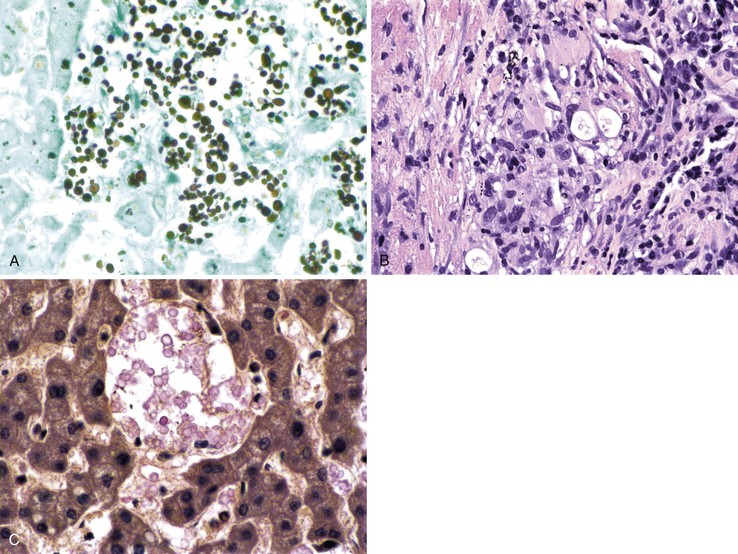

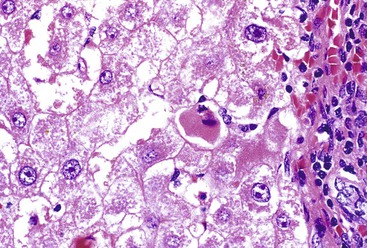

The inflammatory infiltrate in cases of acute viral hepatitis is primarily mononuclear, being composed of lymphocytes, macrophages, scattered eosinophils, and occasional plasma cells and neutrophils (Fig. 46.3). In contrast to chronic viral hepatitis, in which portal and periportal inflammation typically predominates, the inflammatory infiltrate in acute viral hepatitis usually is not concentrated in the portal tracts but spread more evenly throughout the hepatic lobules. Sinusoidal mononuclear cells are often prominent. Kupffer cells are more prominent and more numerous than usual; they are hypertrophic and may contain phagocytized cellular debris and abundant lipofuscin pigment, which is highlighted by staining with periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stain after diastase digestion (Fig. 46.4). Although the necroinflammatory process is typically panlobular, inflammation and necrosis in acute hepatitis may be more pronounced in the centrilobular areas. Bridging necrosis may develop in severe cases. This feature appears as a zone of necrosis that extends from the portal tracts to the central veins, and it is often associated with a more protracted clinical course.

Immunohistochemistry for detection of viral antigens is generally not useful for evaluation of acute viral hepatitis because the virus is rapidly eliminated from liver cells and therefore is not detectable. Serologic tests are reliable and readily available for diagnostic purposes.

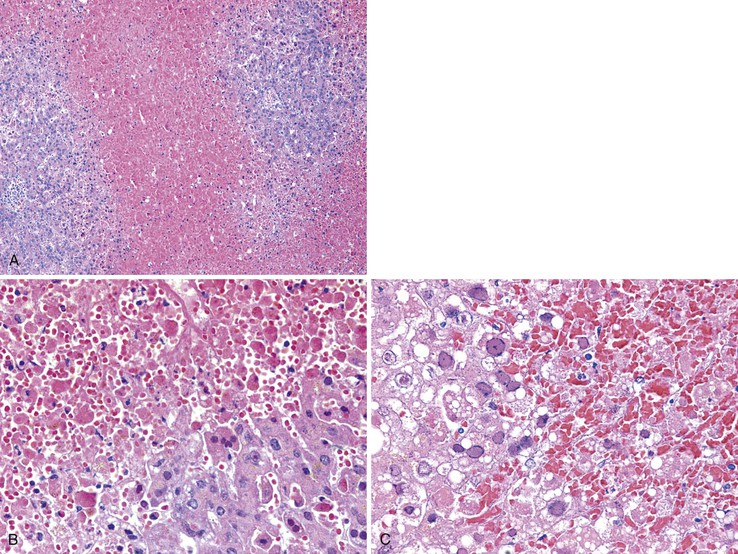

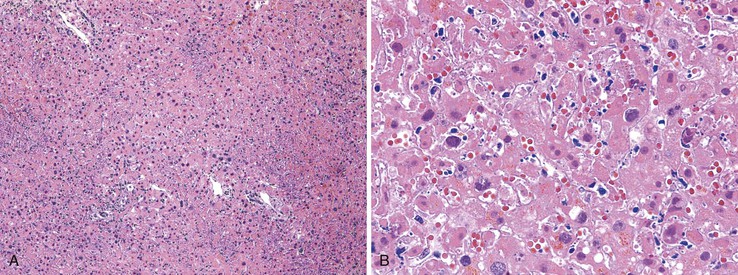

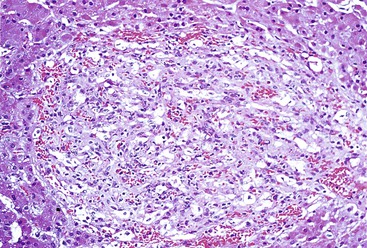

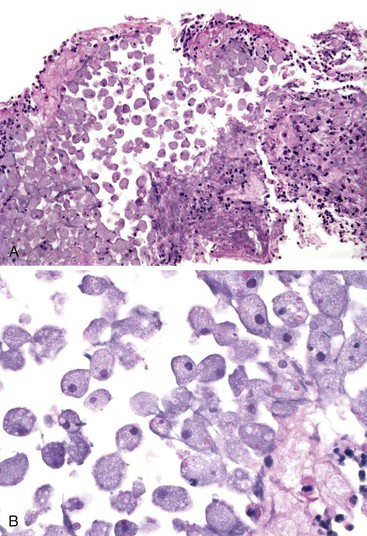

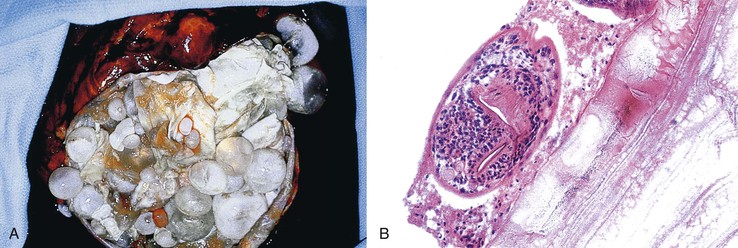

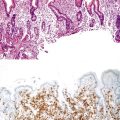

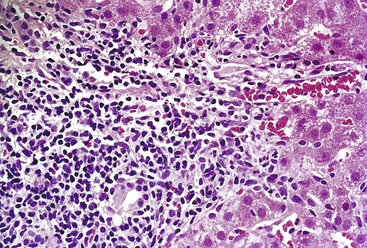

Massive and Submassive Necrosis

In severe cases of acute viral hepatitis, portions of the hepatocyte lobules (submassive necrosis) or entire contiguous lobules (massive necrosis) may undergo necrosis. Submassive necrosis usually involves zone 3 hepatocytes initially but may extend to zone 2 regions with progression. Extensive destruction of hepatic parenchyma results in the clinical syndrome of fulminant hepatic failure. On gross examination, livers with massive necrosis appear shrunken and flaccid, often showing wrinkling of the capsular surface and a mottled appearance of the liver parenchyma. Regenerating nodules of hepatocytes, which are often bile stained, may be irregularly distributed in the liver and may form nodular masses. The degree of necroinflammatory activity is variable, even among patients with a similar clinical course.30 In fulminant cases, one often sees a prominent bile ductular reaction, with associated neutrophils (cholangiolitis), typically located in the peripheral region of the portal tracts (Fig. 46.5). However, the histologic features of submassive or massive hepatic necrosis are not specific for acute viral hepatitis. This pattern of injury can develop as a result of toxic injury, severe drug reaction, or Wilson disease, among other causes. A trichrome stain to highlight connective tissue is useful to distinguish massive hepatic necrosis from cirrhosis by demonstrating the lack of dense collagen deposition in the former. A reticulin stain is also helpful to demonstrate the presence of a collapsed reticulin framework.

Prognostic Factors

Pathologic features of acute viral hepatitis that are predictive of progression to chronicity are difficult to elucidate, in part because of the rarity of liver biopsies from patients with acute hepatitis. Furthermore, in patients with massive hepatic necrosis, an individual liver biopsy may not represent the overall status of the liver, because hepatocyte regeneration and necrosis can vary substantially from region to region.

Differential Diagnosis

Several major entities may be confused with acute viral hepatitis—in particular, chronic viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, and drug-induced hepatitis (Table 46.4). In cases in which the lobular inflammatory component is prominent, a markedly active chronic hepatitis may be confused with acute hepatitis. Some patients with autoimmune hepatitis exhibit an “acute” clinical picture and have a prominent lobular inflammatory infiltrate with extensive necrosis that may be difficult to distinguish from acute viral hepatitis. However, autoimmune hepatitis often reveals prominent plasma cell infiltrates (particularly in the portal tracts), marked periportal inflammation and necrosis, and mild bile duct injury. Also, in autoimmune hepatitis, fibrosis often exists at the time of presentation, even with an acute clinical picture. Serologic tests for autoimmune markers are usually helpful. Viral hepatitis also can be confirmed or excluded based on serologic or PCR-based testing, but some autoimmune markers, such as antinuclear antibody, are not always positive early in the course of autoimmune hepatitis.

Table 46.4

Differential Diagnosis of Acute and Chronic Viral Hepatitis

| Acute | Chronic |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | Autoimmune hepatitis |

| Drug-induced hepatitis | Primary biliary cirrhosis |

| Toxins | Primary sclerosing cholangitis |

| Wilson disease | Wilson disease |

| Other infectious hepatitides | α1-Antitrypsin deficiency |

| Idiopathic | Drug-induced hepatitis |

| Idiopathic |

Drug-induced hepatitis can be indistinguishable from acute viral hepatitis (see Chapter 48 for more detail). The presence of prominent eosinophils, granulomas, sinusoidal dilation, prominent bile ductular reaction, cholestasis, and fatty change may suggest a drug reaction, but these are not considered pathognomonic features. One helpful hint is that acute or chronic forms of hepatitis that do not seem to fit into a discrete morphologic category, or that show overlapping features such as cholestasis and lobular hepatitis, may represent a drug reaction. Obtaining a complete history of drug and toxin exposures is critical to disting repeated drug reactions from viral hepatitis. Furthermore, superimposed drug injury may develop in patients with acute viral hepatitis, so the two entities are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Kupffer cell aggregates are common in resolving acute viral hepatitis and should not be mistaken for non-necrotizing granulomas.

Chronic Hepatitis

Pathologic Features

As mentioned previously, chronic hepatitis is defined clinically as persistent necroinflammatory liver disease. Regardless of the specific etiology, chronic hepatitis is characterized by a combination of portal inflammation, interface (periportal) hepatitis, varying degrees of parenchymal inflammation and necrosis, and, in many cases, fibrosis. This histologic pattern of injury is not specific for chronic viral hepatitis. It may also be seen in many other chronic conditions, such as autoimmune hepatitis, metabolic disorders such as Wilson disease and α1-antitrypsin deficiency, chronic biliary disorders also exhibiting portal inflammation and fibrosis, and various types of drug reactions.

Table 46.5 summarizes the histopathologic features of chronic hepatitis (see also Table 46.3).

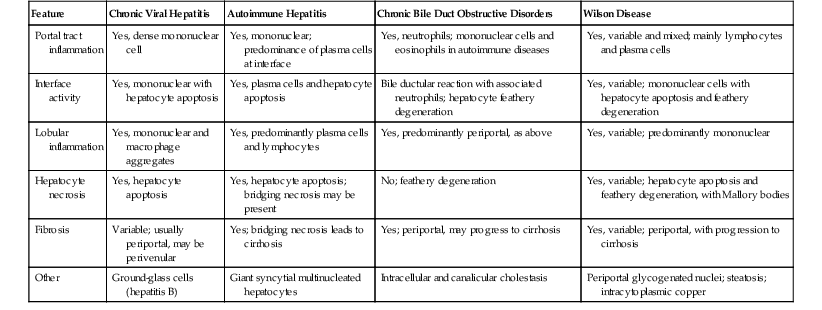

Table 46.5

Histopathologic Features of Common Causes of Chronic Hepatitis

| Feature | Chronic Viral Hepatitis | Autoimmune Hepatitis | Chronic Bile Duct Obstructive Disorders | Wilson Disease |

| Portal tract inflammation | Yes, dense mononuclear cell | Yes, mononuclear; predominance of plasma cells at interface | Yes, neutrophils; mononuclear cells and eosinophils in autoimmune diseases | Yes, variable and mixed; mainly lymphocytes and plasma cells |

| Interface activity | Yes, mononuclear with hepatocyte apoptosis | Yes, plasma cells and hepatocyte apoptosis | Bile ductular reaction with associated neutrophils; hepatocyte feathery degeneration | Yes, variable; mononuclear cells with hepatocyte apoptosis and feathery degeneration |

| Lobular inflammation | Yes, mononuclear and macrophage aggregates | Yes, predominantly plasma cells and lymphocytes | Yes, predominantly periportal, as above | Yes, variable; predominantly mononuclear |

| Hepatocyte necrosis | Yes, hepatocyte apoptosis | Yes, hepatocyte apoptosis; bridging necrosis may be present | No; feathery degeneration | Yes, variable; hepatocyte apoptosis and feathery degeneration, with Mallory bodies |

| Fibrosis | Variable; usually periportal, may be perivenular | Yes; bridging necrosis leads to cirrhosis | Yes; periportal, may progress to cirrhosis | Yes, variable; periportal, with progression to cirrhosis |

| Other | Ground-glass cells (hepatitis B) | Giant syncytial multinucleated hepatocytes | Intracellular and canalicular cholestasis | Periportal glycogenated nuclei; steatosis; intracytoplasmic copper |

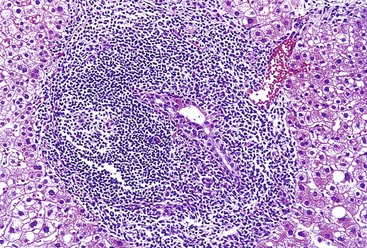

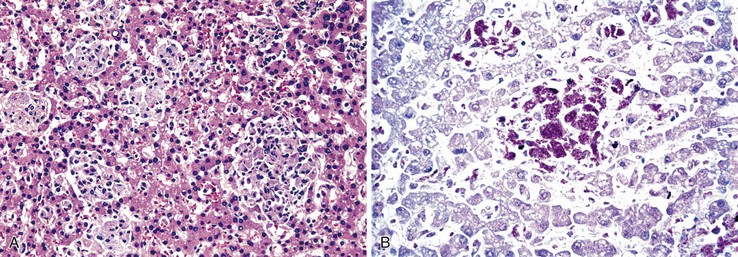

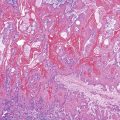

Portal Inflammation

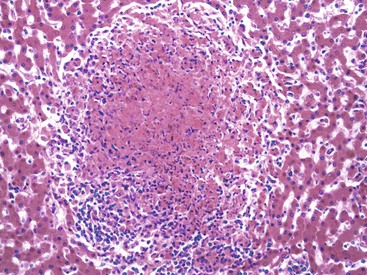

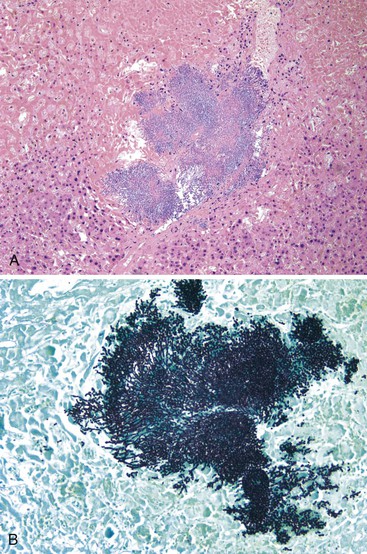

Chronic hepatitis is characterized by the presence of inflammatory infiltrates that involve the portal tracts, which may range from mild and patchy to prominent and diffuse. The infiltrates consist primarily of lymphocytes, often with a variable number of plasma cells. Scattered macrophages, neutrophils, and eosinophils may be found in some cases but are typically a minor component of the infiltrate in chronic viral hepatitis. Lymphoid follicles may be present, particularly in hepatitis C, and germinal centers may also be seen (Fig. 46.6). A bile ductular reaction may be seen at the periphery of portal tracts, but this feature is not specific and usually is not very prominent in viral hepatitis. As with any type of bile ductular reaction, neutrophils are usually associated with the proliferating ductular epithelium as a result of cytokines released by biliary epithelium, and this should not be interpreted as evidence of biliary obstruction or acute cholangitis.

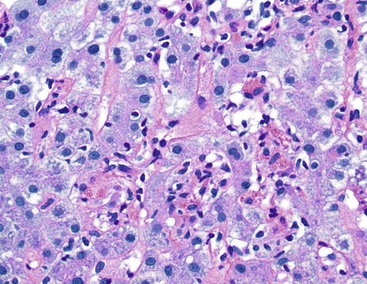

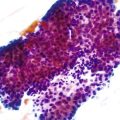

Interface hepatitis, also known as “interface activity” or “piecemeal necrosis,” is an important and common feature of chronic viral hepatitis, although it may be focal or even absent in cases with minimal or mild necroinflammatory activity. More commonly, the portal tracts appear equally involved by the inflammatory process; hence, variation within the liver may result in sampling error with regard to grading activity. Interface hepatitis has two main morphologic components: a mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate involving hepatocytes located at (and disrupting) the limiting plate, and injury or necrosis of periportal hepatocytes. Lymphocytes and plasma cells in the periportal infiltrate are closely associated with degenerating hepatocytes (Fig. 46.7), such that indentation of the cytoplasm of the hepatocytes occurs, and one might even see engulfment of inflammatory cells by hepatocytes. Hepatocytes in areas of interface hepatitis–associated necrosis often appear pale or swollen and show clumping of cytoplasm. Apoptotic bodies may be present as well.

Lobular Necroinflammatory Activity

In chronic viral hepatitis, hepatocyte necrosis is usually variable in severity and spotty in distribution. Lobular disarray, a feature characteristic of acute hepatitis, is not often prominent in chronic hepatitis unless there is marked activity. Apoptotic hepatocytes (acidophil bodies), which are usually more numerous in the periportal areas, may also be scattered in the hepatic lobules (Fig. 46.8). Mononuclear inflammatory cells tend to cluster around injured or dying hepatocytes (Fig. 46.9). Kupffer cells, in areas of spotty hepatocyte necrosis, may contain phagocytosed cellular debris. Hepatocyte swelling may be present in exacerbations of chronic viral hepatitis and may also be associated with zone 3 cholestasis. Regeneration of hepatocytes is recognized by the formation of liver cell plates that are two cells thick and by the formation of regenerating hepatocyte rosettes.

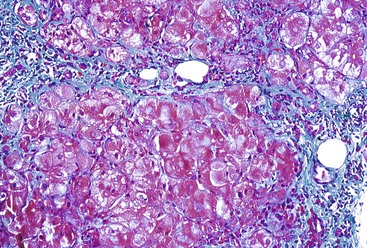

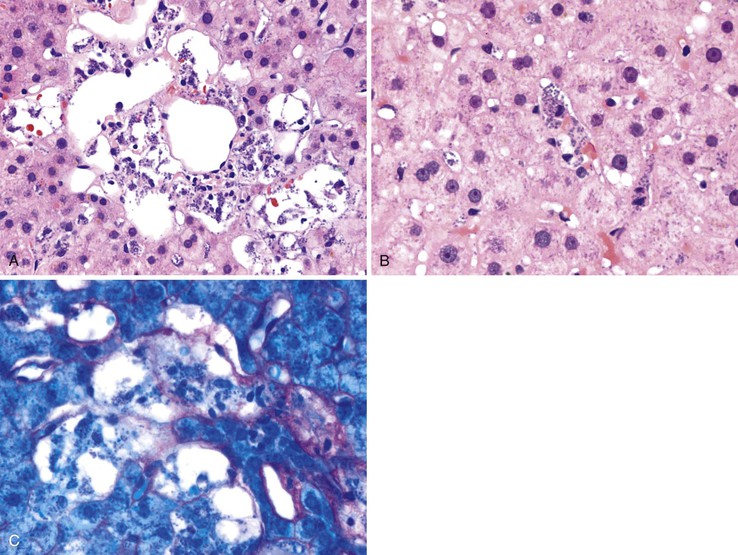

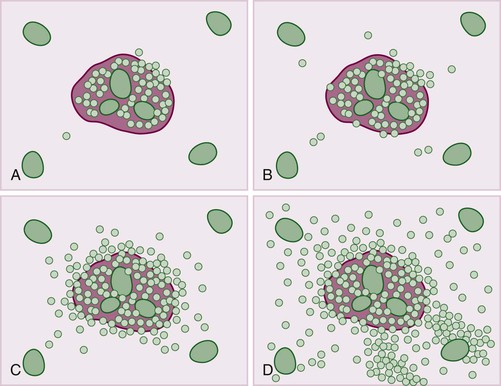

Fibrosis

Progressive fibrosis of the limiting plate, as a result of continued necroinflammatory activity, leads to enlargement of the portal tracts and stellate periportal fibrous extensions (Fig 46.10). Deposition of collagen and other extracellular matrix materials in the space of Disse at the leading edge of periportal fibrosis also results in capillarization of the sinusoids. Portal-portal fibrous septa represent the fibrous linkage of adjacent fibrotic portal tracts (Fig. 46.11). Portal-central fibrous bridges may also develop from superimposed episodes of severe lobular necroinflammatory activity involving zone 3 of the hepatic lobules. Central-central bridges form by the same mechanism but are far less common in chronic viral hepatitis. The end result of bridging fibrosis is cirrhosis, which is usually macronodular or of a mixed micronodular and macronodular type.

Nomenclature and Scoring

In the past, the term chronic active hepatitis was used to describe liver biopsies with interface hepatitis, and the term chronic persistent hepatitis was used for biopsies with portal inflammation but without significant periportal/piecemeal necrosis. This distinction was thought to be clinically important, because chronic persistent hepatitis was considered a relatively benign process without progression to significant liver disease. However, on identification of hepatitis C and on recognition of the waxing and waning nature of the disease and the prolonged time to progression to cirrhosis in many cases, this nomenclature has been abandoned. Currently, the recommended practice is to use the term “chronic hepatitis”31 and include a statement in the pathology report regarding severity of necroinflammatory activity (grade), extent of fibrosis (stage), and etiology.32 Prognostic factors should also be noted in the report (see later discussion).

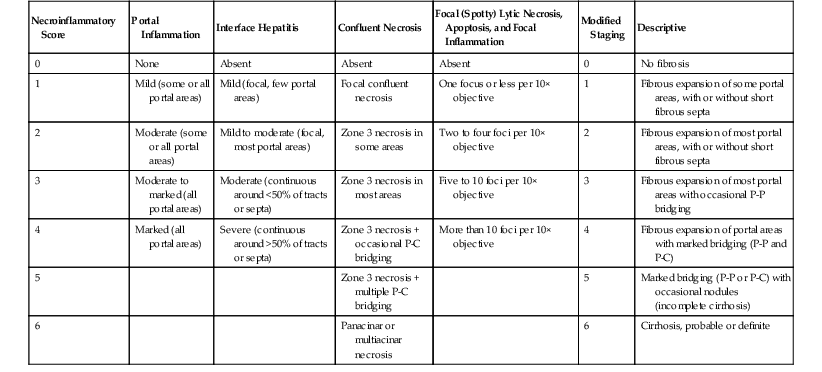

Several different systems for scoring necroinflammatory activity and fibrosis have been developed. The original Knodell system, published in 1981, served as the prototype semiquantitative liver inflammation and fibrosis scoring system.33 With modifications—such as the one proposed by Ishak and co-workers, which separates the grade of inflammation and necrosis from fibrosis—this system is still widely used, particularly in therapeutic trials in which the necroinflammatory activity in pretreatment and posttreatment liver biopsy specimens are compared.34,35 In the original Knodell system, periportal necrosis (with or without bridging necrosis, intralobular necrosis, and inflammation), portal inflammation, and fibrosis are all assigned numeric values, which are then added to obtain a hepatitis activity index (HAI) that ranges from 0 to 22. One major criticism of this system is the inclusion of fibrosis (stage) as a determinant of activity (grade). In practice, the HAI is often modified so that bridging necrosis is dissociated from interface hepatitis, and only the elements that relate to grade are added together to produce the modified HAI (mHAI), with scores that range from 0 to 18; the stage, which indicates degree of fibrosis, is reported separately36 (Table 46.6). An alternative grading system used by the French METAVIR Cooperative Study Group evaluates only two features (periportal necrosis and lobular necroinflammatory activity) instead of three; portal inflammation is excluded because it is considered a prerequisite for the diagnosis of chronic hepatitis, even in cases without parenchymal activity.37

Table 46.6

Ishak Modified Hepatitis Activity Index (HAI) Grading and Staging of Chronic Hepatitis

| Necroinflammatory Score | Portal Inflammation | Interface Hepatitis | Confluent Necrosis | Focal (Spotty) Lytic Necrosis, Apoptosis, and Focal Inflammation | Modified Staging | Descriptive |

| 0 | None | Absent | Absent | Absent | 0 | No fibrosis |

| 1 | Mild (some or all portal areas) | Mild (focal, few portal areas) | Focal confluent necrosis | One focus or less per 10× objective | 1 | Fibrous expansion of some portal areas, with or without short fibrous septa |

| 2 | Moderate (some or all portal areas) | Mild to moderate (focal, most portal areas) | Zone 3 necrosis in some areas | Two to four foci per 10× objective | 2 | Fibrous expansion of most portal areas, with or without short fibrous septa |

| 3 | Moderate to marked (all portal areas) | Moderate (continuous around <50% of tracts or septa) | Zone 3 necrosis in most areas | Five to 10 foci per 10× objective | 3 | Fibrous expansion of most portal areas with occasional P-P bridging |

| 4 | Marked (all portal areas) | Severe (continuous around >50% of tracts or septa) | Zone 3 necrosis + occasional P-C bridging | More than 10 foci per 10× objective | 4 | Fibrous expansion of portal areas with marked bridging (P-P and P-C) |

| 5 | Zone 3 necrosis + multiple P-C bridging | 5 | Marked bridging (P-P or P-C) with occasional nodules (incomplete cirrhosis) | |||

| 6 | Panacinar or multiacinar necrosis | 6 | Cirrhosis, probable or definite |

P-C, Portal-central; P-P, portal-portal.

From Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, et al. Histologic grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1995;22:696-699.

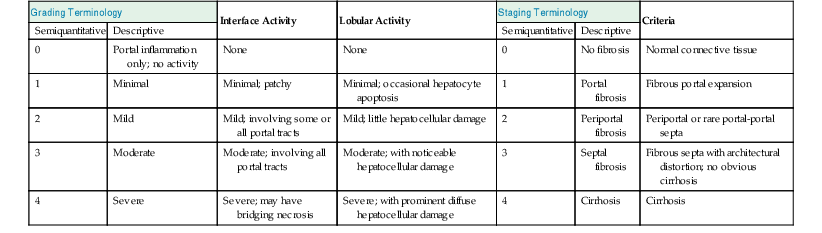

The various semiquantitative grading schemes, although useful for evaluating the effects of a particular treatment regimen in clinical trials, are typically not necessary or clinically relevant for routine pathology reporting of liver biopsies. For everyday diagnostic purposes, simpler schemes are sufficient. For instance, the Batts-Ludwig scoring system (Table 46.7) uses five categories (0 through 4) separately for both grade and stage38 (Fig. 46.12; see also Fig. 46.13). In the Batts-Ludwig system, grade is determined by evaluation of the degree of interface activity (lymphocytic piecemeal necrosis), lobular inflammation, and necrosis. Stage is scored from 0 to 4. A zero score refers to normal connective tissue (no fibrosis). Stage 1 indicates fibrous of portal tracts with expansion; stage 2, periportal fibrosis; stage 3, portal-portal bridging fibrous septa; and stage 4, cirrhosis (Fig. 46.13). Pathologic stage is best evaluated with the use of a Masson trichrome stain, because delicate periportal or early bridging fibrous septa may not be easily apparent on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain.

Table 46.7

Batts-Ludwig Grading and Staging of Chronic Hepatitis

| Grading Terminology | Interface Activity | Lobular Activity | Staging Terminology | Criteria | ||

| Semiquantitative | Descriptive | Semiquantitative | Descriptive | |||

| 0 | Portal inflammation only; no activity | None | None | 0 | No fibrosis | Normal connective tissue |

| 1 | Minimal | Minimal; patchy | Minimal; occasional hepatocyte apoptosis | 1 | Portal fibrosis | Fibrous portal expansion |

| 2 | Mild | Mild; involving some or all portal tracts | Mild; little hepatocellular damage | 2 | Periportal fibrosis | Periportal or rare portal-portal septa |

| 3 | Moderate | Moderate; involving all portal tracts | Moderate; with noticeable hepatocellular damage | 3 | Septal fibrosis | Fibrous septa with architectural distortion; no obvious cirrhosis |

| 4 | Severe | Severe; may have bridging necrosis | Severe; with prominent diffuse hepatocellular damage | 4 | Cirrhosis | Cirrhosis |

From Batts KP, Ludwig J. Chronic hepatitis: an update on terminology and reporting. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:1409-1417.

Pathology of Specific Types of Chronic Viral Hepatitis

Refer to Table 46.5 for a summary of the histopathologic features of chronic viral hepatitis.

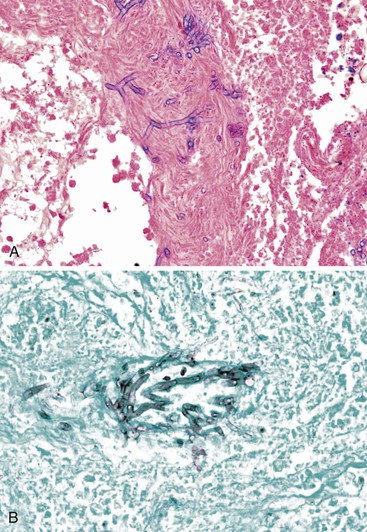

Chronic Hepatitis B

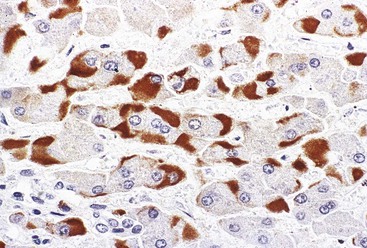

Hepatitis B virus infection is characterized by the presence of varying degrees of portal inflammation, interface activity, spotty lobular inflammation, and necrosis. Patients with bridging or confluent necrosis are likely to have more advanced degrees of fibrosis (higher-stage disease).39 Ground-glass cells containing abundant HBsAg within smooth endoplasmic reticulum may be recognized on H&E-stained tissue sections (Fig. 46.14). However, they are not present in all cases, and they are more likely to be numerous in biopsy samples that contain little necroinflammatory activity. When present, they denote active viral replication. Mimics or “pseudoground-glass” hepatocytes have been described in the absence of HBV infection.40 HBcAg accumulation within hepatocyte nuclei produces a “sanded” appearance, but these changes are also seen in HDV infection and are difficult to recognize on routine histologic stains. Identification of cytoplasmic HBsAg may be facilitated by use of one of the Shikata stains, such as Victoria blue, orcein, or aldehyde fuchsin, or by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 46.15). HBcAg accumulation may also be identified with the use of immunohistochemical stains (Fig. 46.16). Cytoplasmic or membranous expression of this antigen correlates with higher levels of necroinflammatory activity.41

Delta Virus Infection

Sanded hepatocyte nuclei may be seen in cases of hepatitis B with delta virus superinfection. Delta antigen may be demonstrated in nuclei of hepatocytes by immunohistochemical stains. Overall, the histopathologic picture resembles hepatitis B without delta infection, but the degree of necroinflammatory activity is often more severe.

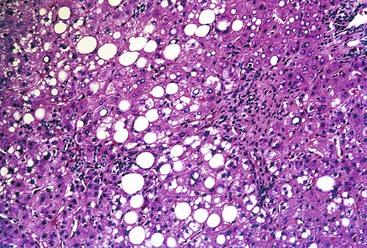

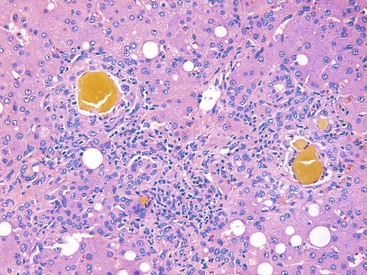

Hepatitis C

Histologically, most cases of chronic hepatitis caused by HCV tend to be mild in degree. Characteristic features are portal lymphoid aggregates and follicles, bile duct infiltration by lymphocytes, and steatosis. Dense aggregates of lymphocytes in the portal tracts are a distinctive, but not pathognomonic, feature of hepatitis C and one that is readily apparent on low-power examination (see Fig. 46.6). The degree of bile duct injury in hepatitis C is usually mild, and duct loss does not occur (Fig. 46.17). Steatosis in hepatitis C is usually macrovesicular; it is associated both with infection by HCV genotype 3, in which the virus is thought to be directly steatogenic, and with metabolic aberrations including insulin resistance in patients with chronic hepatitis C.42 Steatosis and insulin resistance are associated with more severe fibrosis, poor treatment response, and increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis C (Fig. 46.18)).43–46 Non-necrotizing granulomas occur in a small percentage of cases, but other concurrent causes of granulomas should always be excluded.47 The presence of scattered lobular acidophil bodies is a common feature of chronic hepatitis C. Mallory hyaline-like cytoplasmic inclusions have also been reported and have been associated with progression of fibrosis.48 Immunoperoxidase staining for HCV has been reported in paraffin-embedded tissue, but these stains are difficult to interpret and therefore are not often used in routine clinical infestigations.49

Combined Viral Infections

Combined infections with HBV and HCV are not uncommon, occurring in more than 10% of patients with hepatitis B.50 In some patients, superinfection is associated with viral interference, which results in suppression of the preexisting virus by the more recently acquired virus. If coreplication of both HCV and HBV does occur, as evidenced by the presence of nucleic acids from both viruses, liver disease is likely to be more active and to show faster progression. The histologic features of hepatitis C often predominate in liver biopsy specimens.

Coinfection with HCV or HBV (or both) and HIV is also common. Histologic evaluation of liver biopsy specimens is complicated by the fact that HIV may directly affect the liver, and HAART also causes hepatotoxicity. Early studies of coinfected individuals showed an increased severity of liver disease, including necroinflammatory scores and fibrosis, compared with patients infected by HCV alone. However, subsequent studies showed that after stratification of patients by the status of their liver function test results, there were no significant differences in the degree of inflammation and fibrosis in coinfected versus solely HCV-infected individuals.51–53 More recently, the severity of liver biopsy changes has been associated with the HIV RNA level at the time of biopsy.54

Prognostic Factors

Factors associated with progression of chronic viral hepatitis to cirrhosis may be divided into those related to specific viruses, host-related factors (see Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C), and extraneous factors (e.g., alcohol use). For hepatitis C, development of chronic hepatitis is not related to the amount of virus at initial exposure. Viral genotype may be important in the progression of HCV infection. For instance, genotype 1 is associated with more severe disease than genotype 2.10,55 However, other studies have not confirmed this association.56 Host-related factors for disease severity are incompletely defined, but age at infection and gender appear to be relevant. Males and older individuals are more likely to show progression of fibrosis.56,57 Alcohol consumption increases replication of hepatitis C and is associated with more severe disease.11 In general, the grade of hepatic necroinflammatory activity in liver biopsy specimens correlates with the serum HCV RNA level,58 and the rate of progression to cirrhosis correlates with high-grade activity and advanced stage in initial liver biopsies.59 Hepatic steatosis is also associated with increased disease severity and is more commonly seen in infections with genotype 3b, as previously discussed.57,60 Accumulation of iron in hepatocytes and Kupffer cells in hepatitis C may influence the disease course and response to therapy adversely.57,61 However, many patients with chronic viral hepatitis, including hepatitis C, have abnormal results on serum iron studies but normal or only scant iron accumulation within the liver tissue.

Differential Diagnosis

The morphologic patterns of chronic viral hepatitis may resemble a variety of hepatitides and therefore are not specific (see Table 46.5). The initial distinction should include separation of acute from chronic hepatitis and then chronic viral hepatitis from other forms of chronic hepatitis, such as autoimmune hepatitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC), metabolic disorders, and drug reactions. Distinction from acute hepatitis rests primarily on the pattern of lobular inflammation and necrosis, and the finding of a predominance of portal inflammatory changes in cases of chronic hepatitis; fibrosis, in particular, is a cardinal sign of disease chronicity. However, in some cases, identification of acute versus chronic hepatitis may not be possible on morphologic grounds alone; clinical evidence of chronic disease can be helpful.

Early in the course of disease, portal lymphocytic infiltrates in patients with PBC may resemble chronic viral hepatitis, particularly hepatitis C. Florid-duct lesions and loss of interlobular bile ducts are helpful distinguishing features, because these lesions occur in PBC but not in chronic viral hepatitis. Bile ducts may be infiltrated mildly by lymphocytes in chronic hepatitis C, but the degree of inflammation and duct destruction is not nearly as severe as in PBC. Furthermore, portal granulomas, especially those associated with injured bile ducts, are not a feature of viral hepatitis. Chronic cholestasis is not a feature of precirrhotic chronic viral hepatitis and, by definition, indicates a chronic cholestatic condition. Furthermore, demonstration of increased copper or copper-binding protein by copper stains is helpful to suggest the presence of a chronic biliary disorder. Of course, knowledge of the status of viral serologic studies and other titers, such as the antimitochondrial antibody level, are most helpful in this differential diagnosis.

The morphologic features of PSC, in its early stages, may also overlap with chronic viral hepatitis. Both may show a marked portal lymphocytic infiltrate with interface hepatitis; however, this distinction may be particularly difficult in cases of childhood PSC. Once again, bile duct loss suggests a chronic biliary process; alkaline phosphatase levels are typically higher in PSC, but cholangiography is usually necessary to establish a final diagnosis of PSC. The classic “onion-skinning” periductal concentric sclerosing lesions of PSC are not seen in viral hepatitis. In patients with ulcerative colitis and a liver biopsy that shows a pattern of inflammation suggestive of chronic hepatitis, the possibility of PSC should always be strongly considered.

Chronic viral hepatitis may be histologically indistinguishable from autoimmune hepatitis. The presence of numerous plasma cells in the portal inflammatory infiltrate and plasma cells in the lobules is suggestive of autoimmune hepatitis, but an autoimmune-like pattern of hepatitis C has also been described, and clinical correlation is often necessary to reliably distinguish these entities. Bile duct infiltration by lymphocytes is also seen in autoimmune hepatitis and therefore cannot be used to distinguish this condition from hepatitis C. Once again, serologic studies are usually helpful and often diagnostic.

Wilson disease may also reveal a chronic hepatitis pattern of injury on liver biopsy, and it should always be considered as a possibility in biopsies from young patients with negative viral serology results. Low serum ceruloplasmin is suggestive, but quantitative copper studies on liver tissue are ultimately necessary for definitive diagnosis. α1-Antitrypsin deficiency may also reveal a pattern of injury resembling chronic hepatitis; accumulation of PAS-positive, diastase-resistant cytoplasmic globules in periportal hepatocytes helps identify this disorder, particularly in liver biopsies from adults.

The spectrum of drug-induced injury in the liver is wide (see Chapter 48). Many types of drugs cause a chronic hepatitis morphologic pattern of injury that can be difficult to distinguish from other causes, such as viral or autoimmune hepatitis. Drugs that commonly cause chronic hepatitis include methyldopa, isoniazid, nitrofurantoin, dantrolene, and sulfonamides. As mentioned earlier, patterns of liver injury that show mixed features, prominent eosinophils, and cholestasis, or simply do not seem to fit in any discrete etiologic category, should always be considered for a drug reaction.

Mild lobular hepatitis, with spotty hepatocyte necrosis and a scant mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate, may be seen as a nonspecific finding in a variety of systemic and immune-mediated disorders and in patients with an intraabdominal inflammatory process. These changes may mimic mild acute or chronic hepatitis but are considered reactive in nature. In some cases, morphologic changes of chronic hepatitis in a liver biopsy specimen are not associated with a specific etiology after extensive serologic and clinical testing, and these cases may be labeled “cryptogenic” or “idiopathic.” However, a drug reaction should always be considered in this setting.

See Chapters 47 and 48 for more details on the differential diagnosis of hepatitis.

Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C

HCV is estimated to infect approximately 170 million people worldwide and is the most common bloodborne chronic infection in the United States.8,62–63 Despite a recent decline in the incidence of acute HCV infection and increasing understanding of its pathogenesis, the treatment of chronic hepatitis C remains challenging. Chronic HCV infection is still the most common indication for liver transplantation in the United States and Europe.62,64

The treatment of chronic HCV infection is complicated for several reasons. Patients may be asymptomatic after their initial acute infection. Furthermore, a protracted period of time between initial infection and treatment has been associated with a poor response to therapy. Patients who are symptomatic often reveal advanced liver disease and respond poorly to therapy. In addition, biochemical tests, such as serum aminotransferases, are poor predictors of the severity of liver disease. Despite these limitations, several patient and viral characteristics have been associated with a poor response to treatment, including patient age greater than 40 years, male gender, high body weight, high viral load (>1×106 HCV RNA copies per mL), cirrhosis, renal insufficiency, and infection with HCV genotype 1a or 1b.62,63 However, detection of a single-nucleotide polymorphism in the IL28B gene has been found to be a better predictor of spontaneous clearing of HCV infection and sustained viral response after therapy than pretreatment RNA level, fibrosis stage, age, or gender.64,65

Detailed treatment guidelines have been put forth by European and American liver associations.64,65 Until recently, standard therapy for chronic HCV infection included the use of pegylated interferon and ribavirin.64,65 Interferon-α is a cytokine that increases the innate antiviral immune response and results in decreased replication of HCV. Pegylated interferon has an increased half-life and can be administered as a weekly dose. Ribavirin is an oral nucleoside analogue with poorly understood antiviral activity, as well as immune-modulating activity.62,63 More recently, however, the availability of direct-acting antiviral agents and protease inhibitors has resulted in improved sustained viral response rates (defined as the absence of HCV RNA in serum by a sensitive test at the end of treatment and 6 months later).64,65

Cirrhosis and Regression of Fibrosis

Despite continued investigation into new therapeutic options for HCV infection, some studies show that as many as 40% of patients with chronic HCV infection will progress to cirrhosis and become candidates for orthotopic liver transplantation. Unfortunately, recurrence of HCV in liver transplants is virtually universal (see Chapter 52 for details).

Evaluation of liver biopsy specimens remains the gold standard for determination of the degree of fibrosis, despite limitations such as inadequate sampling and interobserver and intraobserver variability. The potential for reversal of liver fibrosis has long been controversial (see Chapter 50). For many years it was believed that, once established, scar tissue in the liver cannot be resorbed or replaced by healthy liver tissue. In the 1970s, several investigators questioned this assumption and investigated the potential reversibility of liver cirrhosis and the role of proteins such as collagenases in hepatic remodeling.66 Some 40 years later, the idea of “regression” of hepatic fibrosis is more widely accepted and has been demonstrated in several rodent models and in human patients with autoimmune hepatitis, biliary obstruction, fatty liver disease, or viral hepatitis.66–70 Basic science studies have also led to a better understanding of the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis through animal models, cell culture, and biochemical assays.67,68 For instance, although hepatic stellate cells play a key role in hepatic wound healing and in matrix deposition and degradation, neutrophils and macrophages have also been shown to play a role in the degradation of matrix. Matrix metalloproteinases, which cleave collagen and other matrix components, may also be important in hepatic remodeling. Levels of tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases have been shown to decrease with fibrosis regression and clearance of activated hepatic stellate cells. The nuclear factor-κ B (NF-κB) pathway, transforming growth factor-β, and nerve growth factor also play a role in the complicated orchestration of matrix generation and degradation.66–71 (See Chapter 50.)

Other Viral Infections of the Liver

A wide variety of (nonhepatotropic) viruses may affect the liver and cause a wide range of clinical manifestations, from mild, asymptomatic elevations in serum aminotransferases to dramatic and even fatal hepatic necrosis (Table 46.8). Nonhepatotropic viruses are often seen in neonates and in immunocompromised persons as part of disseminated infection.

Table 46.8

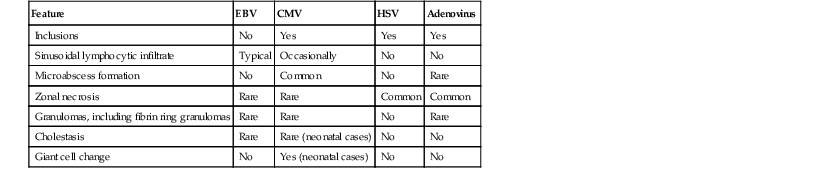

Histologic Comparison of Hepatic EBV, CMV, HSV, and Adenovirus Infection

| Feature | EBV | CMV | HSV | Adenovirus |

| Inclusions | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sinusoidal lymphocytic infiltrate | Typical | Occasionally | No | No |

| Microabscess formation | No | Common | No | Rare |

| Zonal necrosis | Rare | Rare | Common | Common |

| Granulomas, including fibrin ring granulomas | Rare | Rare | No | Rare |

| Cholestasis | Rare | Rare (neonatal cases) | No | No |

| Giant cell change | No | Yes (neonatal cases) | No | No |

CMV, Cytomegalovirus; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; HSV, herpes simplex virus.

Epstein-Barr Virus

The liver is affected in more than 90% of cases of EBV-related mononucleosis. Hepatic involvement is indicated by elevated aminotransferases,72 often accompanied by the other symptoms of mononucleosis. Jaundice occurs in only a minority of patients. Fulminant liver failure secondary to EBV infection has also been described, particularly in immunocompromised children73 but also in healthy patients. Hepatitis (or fulminant hepatic failure) caused by EBV may not be accompanied by typical features of mononucleosis.74 EBV hepatitis may also be associated with autoimmune phenomena, including autoimmune hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and a positive antinuclear antibody value.75

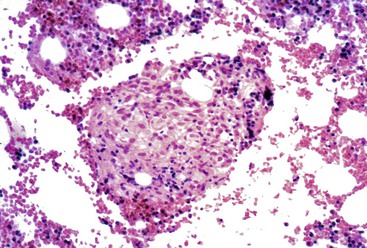

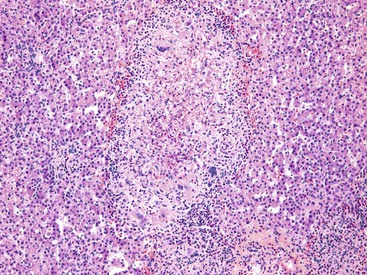

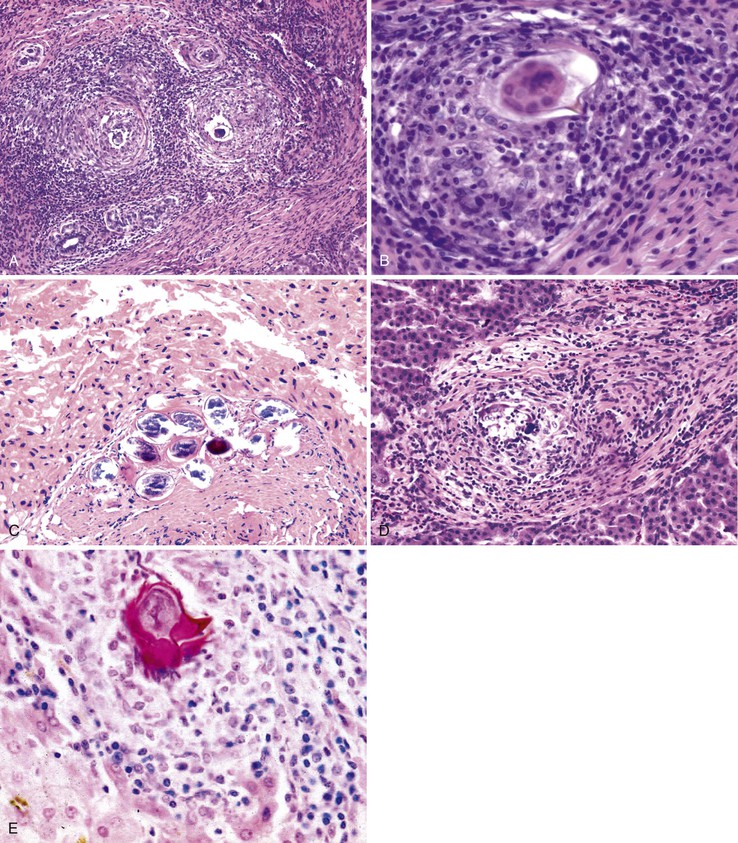

The most characteristic histologic feature in otherwise healthy patients is the presence of a diffuse lymphocytic sinusoidal infiltrate arranged in a single-file, “string-of-beads” pattern, with occasional scattered atypical lymphocytes (Fig. 46.19). Focal apoptotic hepatocytes and steatosis may also be present. Cholestasis is not typical, but cholestatic hepatitis has been described in the context of EBV hepatitis.72,76,77 Small Kupffer cell clusters and, rarely, discrete, noncaseating granulomas or fibrin ring granulomas may be seen as well. Progression to chronic hepatitis or cirrhosis is rare. EBV hepatitis may also develop after solid organ transplantation, particularly after liver transplantation. The histologic picture may be more severe in this context, showing a marked portal and periportal inflammatory infiltrate containing numerous atypical lymphocytes, immunoblasts, and plasma cells as well as mild bile duct damage and prominent necrosis.78

Confirmatory tests include serologic, immunohistochemical, in situ hybridization studies for EBV, and serum or tissue PCR.79 However, serologic studies may be unreliable in very young children and in immunocompromised patients. The differential diagnosis includes other types of viral infections (e.g., CMV). An EBV-like lobular sinusoidal lymphocytic infiltrate may be seen in transplant recipients with recurrent hepatitis C. Hepatic involvement by leukemia or lymphoma should also be excluded when atypical lymphocytes are numerous. For a detailed discussion of EBV-related posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorders, refer to Chapter 52.

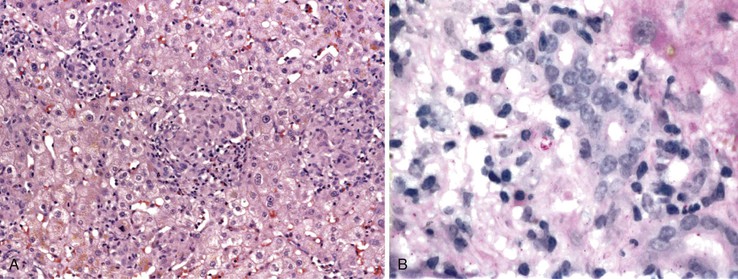

Cytomegalovirus

Patients with CMV hepatitis may show an increase in aminotransferase levels, a cholestatic pattern of enzyme elevation, or both. The clinical and histologic features of CMV hepatitis depend on the immune status of the host.

Cytomegalovirus Infection in Otherwise Healthy Patients

Primary CMV infection in otherwise healthy people is usually self-limited, although a mononucleosis-like syndrome may occur in some. CMV hepatitis in immunocompetent individuals is often part of a multiorgan infectious process.80 Rare cases of fulminant liver failure have been described, but chronic liver disease does not develop in this patient population. Liver biopsy findings resemble those of EBV infection. However, neither viral inclusions nor immunohistochemically demonstrable CMV antigen is typically evident in infected patients.81

Cytomegalovirus Infection in Immunocompromised Patients

CMV infection of the liver is more common in immunocompromised persons, and CMV is the single most important pathogen in solid organ transplant recipients of all types.80 CMV infection may be acquired by primary infection, reactivation, or superinfection by a new strain in a previously seropositive patient.82 Infection occurs approximately 2 to 16 weeks after solid organ transplantation, and symptoms range from mild to life-threatening. Although any organ may be involved, hepatic involvement often predominates. In liver transplant recipients, the allograft is the most common site of involvement82,83 (see Chapter 52). In immunocompromised patients, CMV hepatitis is caused primarily by the cytopathic effects of the virus.84,85

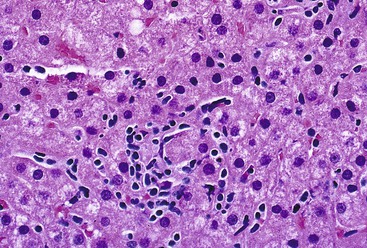

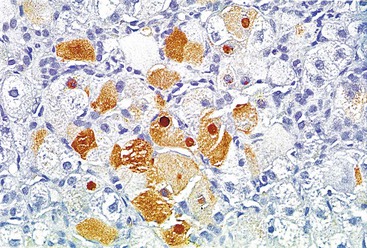

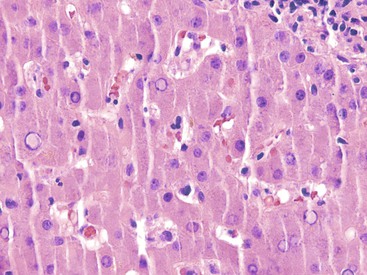

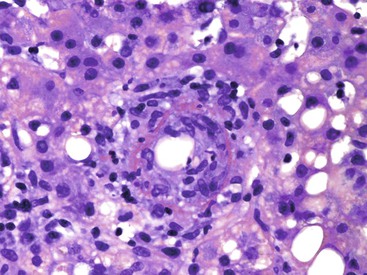

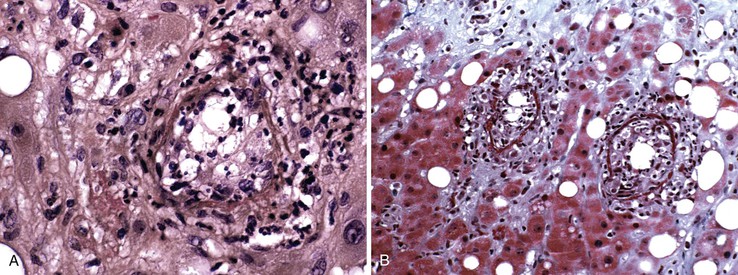

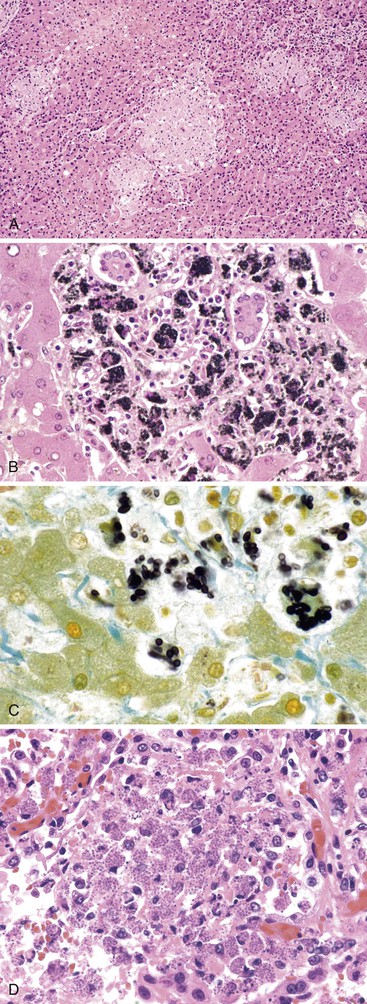

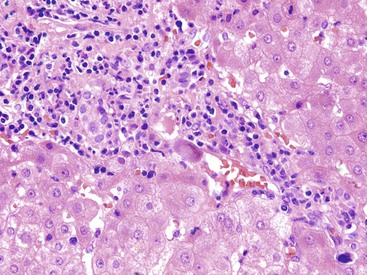

Infected cells show both nuclear and cytoplasmic enlargement (hence the name, “cytomegalovirus”). Characteristic “owl’s eye” intranuclear viral inclusions (Fig. 46.20) and basophilic granular intracytoplasmic inclusions (Fig. 46.21) may be seen on routine H&E preparations. Inclusions may be present in the nucleus or cytoplasm of any liver cell type, Infected cells are often surrounded by a neutrophilic microabscess (Fig. 46.22), either with or without admixed mononuclear cells. The number of viral inclusions may be extremely variable, and the diagnosis is easily missed when few inclusions are present. In addition, some infected cells may have only a minimal amount of associated inflammation. However, the presence of typical neutrophilic microabscesses centered on injured and dying hepatocytes in a transplant patient should always trigger suspicion of CMV infection. Other associated features include hepatocyte apoptosis and focal necrosis, portal and lobular mononuclear inflammation, and rare granulomas, including those of the fibrin ring type.86,87 Chronic liver disease does not occur in CMV-infected patients.

Cytomegalovirus Infection in Neonates

Liver involvement is a common feature of neonatal and perinatal CMV infection. Affected infants usually have hepatosplenomegaly and jaundice. Histologically, liver biopsy findings resemble opportunistic CMV infection, often with a variable number of typical viral inclusions. A wide range of other pathologic alterations also may be seen, such as portal inflammation, marked cholestasis, giant cell transformation, focal necrosis, and prominent extramedullary hematopoiesis.88 Bile duct damage and obliteration are rarely present, although CMV (as well as several other viruses) has been associated with biliary atresia and paucity of intrahepatic bile ducts. In rare cases, portal or sinusoidal fibrosis may develop.

Useful diagnostic aids include viral culture, PCR assays, in situ hybridization, and CMV serologic studies and antigen tests.82 Isolation of CMV in culture does not imply active infection, because the virus may be excreted for months to years after the primary infection.89

The differential diagnosis in otherwise healthy persons includes other viral infections (e.g., EBV). The differential diagnosis in immunocompromised patients includes herpesvirus and adenovirus infection. Other causes of microabscesses, such as ischemia, should also be considered, particularly in transplant recipients.90 In neonates, the differential diagnosis includes other causes of neonatal hepatitis and congenital disorders of bile ducts, as discussed previously.

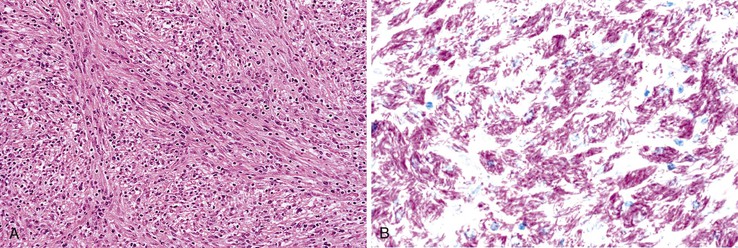

Herpes Simplex Virus

Herpesvirus hepatitis is usually a disease of immunocompromised patients as part of disseminated infection, although it can rarely be seen in otherwise healthy persons.91 Hepatic manifestations may dominate the clinical picture. Neonates, children who are malnourished or recovering from other infections (particularly measles), pregnant women, and immunocompromised persons are at significant risk of serious infection.92

Clinically, patients are typically febrile, and some have concomitant oral or mucosal herpetic lesions, pharyngitis, headache, abdominal pain, or myalgias. Importantly, patients with herpes simplex virus (HSV) hepatitis may lack the typical mucosal herpetic lesions.93,94 Aminotransferases are typically quite elevated, and hepatomegaly is frequent. A rapidly progressive course associated with a high mortality rate is common; therefore, early liver biopsy is invaluable. Both infants and adults with fulminant HSV infection have successfully undergone liver transplantation.93,95

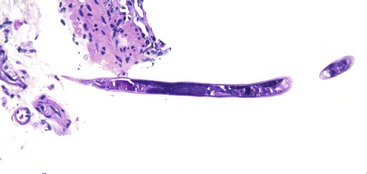

Grossly, livers infected with HSV are enlarged and mottled and show multiple foci of necrosis, often surrounded by a zone of hemorrhage.91,92 Histologically, randomly distributed (“geographic”) zones of necrosis, ranging from microscopically focal to macroscopically visible with the naked eye, are characteristic. Portal tracts may be spared. The necrotic zones are often surrounded by congestion and extravasated red blood cells; however, inflammation is usually minimal.91,92 Typical viral inclusions, both Cowdry type A and ground-glass cells, are usually present in hepatocyte nuclei, particularly at the periphery of necrotic areas (Fig. 46.23). Inclusions may be single or multiple.

Viral culture is a valuable diagnostic aid. Immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridization, and PCR assays can also be very useful. PCR may be performed on liver or blood, but detection of HSV in blood may lag behind detection of the virus in the liver in severely immunocompromised patients.95

The differential diagnosis includes predominantly other types of viral infections, such as CMV and adenovirus. CMV does not cause the typical necrotic pattern of HSV, and adenovirus inclusions are usually more homogeneous in appearance. Although viral hemorrhagic fever can cause focal necrosis, widespread zonal necrosis and nuclear inclusions are typically absent. Varicella-zoster produces histologic lesions identical to HSV, but varicella-infected patients typically also have a skin rash.91,92 Ischemia or toxic (drug) injury (e.g., acetaminophen) can cause widespread necrosis, although the necrosis is usually more zonal in these conditions (particularly zone 3), and viral inclusions are absent.91

Human Herpesvirus 6

Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) was originally isolated in the mid-1980s from patients with AIDS or lymphoproliferative disorders.96 Primary infection by this lymphotropic virus affects mainly young children, who have benign and self-limited symptoms, including a viral exanthem. However, the virus may reactivate, typically in immunocompromised patients and transplant recipients. Based on serologic tests and PCR assays performed on blood, HHV-6 is associated with hepatitis and fulminant liver failure, most notably in infants, children, and transplant recipients.96–98 Most cases of HHV-6 in solid organ transplantation are likely related to reactivation of recipient virus, although primary HHV-6 infections in naïve recipients have also been reported.97,98 Infections are usually asymptomatic, although hepatitis has rarely been described in this population.97,98 Fulminant liver failure has rarely been reported in immunocompetent adults.99,100 The pathologic findings in HHV-6 infection have not been well described but may resemble those of EBV infection in the liver.99,100 Useful diagnostic tests include immunohistochemistry, serologic assays, and PCR on blood or liver tissue.98

Enteric Viruses

The enteric group of viruses only rarely infect the liver, but when they do, fatal hepatic necrosis is often the end result. Adenovirus is most commonly implicated, usually in immunocompromised patients (particularly children). Clinically, the presenting symptoms may include fever, hepatomegaly, and markedly elevated aminotransferase levels. Concomitant pneumonia and diarrhea reflect disseminated infection.101

Grossly, livers are enlarged and mottled, with foci of necrosis. Histologic features resemble those of HSV infection, showing widespread zones of necrosis, typically with minimal associated inflammation. Intranuclear viral inclusions, known as “smudge cells,” may be present. They may mimic the viral inclusions of HSV but are darker and more homogeneous (Fig. 46.24). Some cases feature randomly distributed, well-circumscribed inflammatory lesions consisting of mononuclear cells and granulocytes, with rare inclusions located at the periphery of the inflammatory infiltrate. Necrosis is usually much less prominent in these cases. Granulomas have been described as well.102

Useful diagnostic aids include immunohistochemistry, stool or tissue examination by electron microscopy, viral culture, and PCR. The differential diagnosis includes other types of viral infections, particularly HSV. Coxsackieviruses and echoviruses may induce a similar histologic profile, but inclusions are seldom present.

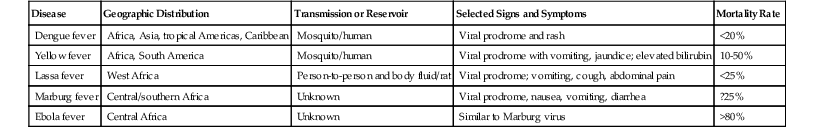

Viral Hemorrhagic Fever

The geographic distribution, transmission, and clinical course of this diverse group of viruses are quite variable103–106 (Table 46.9). Death from liver failure is rare in viral hemorrhagic fevers, with the exception of yellow fever. Liver pathology is similar regardless of the type of virus. Useful adjunctive tests include serologic studies and immunohistochemistry, although these are not widely available. Patients usually experience a viral prodrome consisting of fever, headache, and myalgia, followed by hemorrhagic manifestations. Elevated aminotransferases and hepatomegaly are common. Histologically, viral hemorrhagic fever features foci of coagulative necrosis but with only minimal inflammation. Necrosis is usually multifocal and randomly distributed, rather than massive. Yellow fever produces a midzonal pattern of injury characterized by hepatocyte necrosis and steatosis.107 Some foci of necrosis may be surrounded by abundant macrophages.104,108 Steatosis is variable, and cholestasis is not usually prominent. Adjacent intact hepatocytes may show regenerative changes and ballooning degeneration. Inclusions are not typically present.

Table 46.9

Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers

| Disease | Geographic Distribution | Transmission or Reservoir | Selected Signs and Symptoms | Mortality Rate |

| Dengue fever | Africa, Asia, tropical Americas, Caribbean | Mosquito/human | Viral prodrome and rash | <20% |

| Yellow fever | Africa, South America | Mosquito/human | Viral prodrome with vomiting, jaundice; elevated bilirubin | 10-50% |

| Lassa fever | West Africa | Person-to-person and body fluid/rat | Viral prodrome; vomiting, cough, abdominal pain | <25% |

| Marburg fever | Central/southern Africa | Unknown | Viral prodrome, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea | ?25% |

| Ebola fever | Central Africa | Unknown | Similar to Marburg virus | >80% |

Other viruses that cause hepatitis include measles (rubeola), rubella, and parvovirus, which may affect the liver in the context of hydrops fetalis. Primary HIV infection has been shown to cause liver involvement similar to EBV-related mononucleosis, as well as neonatal hepatitis.109 Fulminant hepatic failure caused by varicella-zoster has been rarely reported as well, in both immunocompromised and apparently immunocompetent patients.110–112

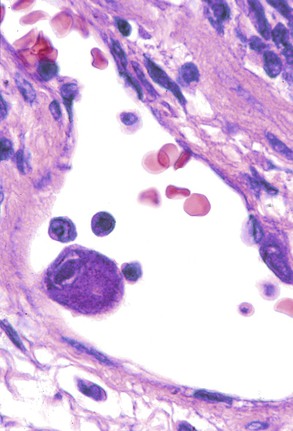

The virus-associated (reactive) hemophagocytic syndrome (VAHS) is strongly associated with viral infection, particularly EBV, although other viruses have also been implicated.113–116The presenting symptoms include fever, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, peripheral blood cytopenias, and lymphadenopathy. Many patients experience a viral-like prodrome. Adult patients are often immunocompromised; children with VAHS usually do not reveal an underlying immunodeficiency. Most patients recover spontaneously. Histologic features include cytologically benign hemophagocytic histiocytes within both portal tracts and sinusoids. Kupffer cells may be hypertrophic and may show hemophagocytosis (Fig. 46.25) as well as siderosis.117 Focal hepatocyte necrosis may be present.

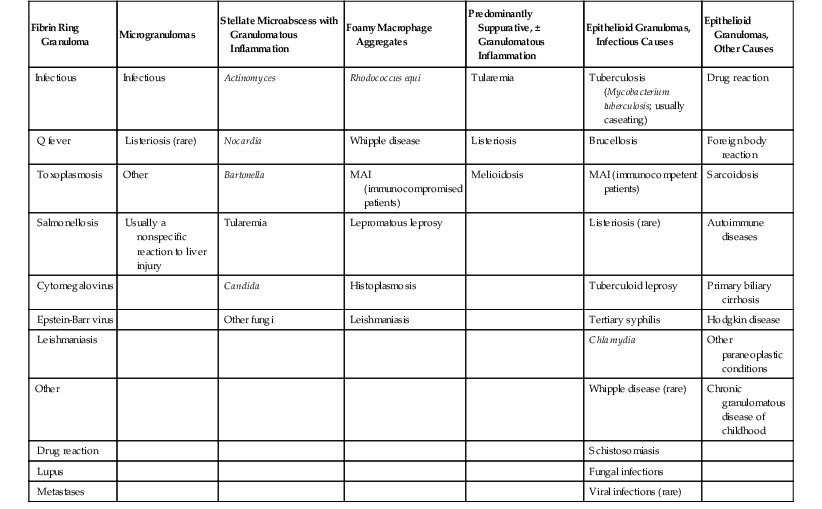

Bacterial Infections of the Liver

Suppurative Bacterial Infections

Suppurative hepatic inflammation is usually accompanied by hepatocyte necrosis. Lesions may range from microscopic microabscesses to macroscopic pyogenic abscesses. A general discussion of suppurative hepatic abscess is presented here, followed by a more detailed discussion of specific types of bacterial suppurative infections.

Pyogenic Bacterial Abscess

Pyogenic abscesses secondary to bacterial infection typically occur in older patients. Symptoms are usually nonspecific and include abdominal pain, hepatomegaly, malaise, and fever. Jaundice is rare.118 Aminotransferases are usually elevated, but often with a disproportionately high alkaline phosphatase level. The mortality rate is high, especially if the abscess is associated with sepsis. In children, pyogenic liver abscesses may signal the presence of immunodeficiency (e.g., chronic granulomatous disease).119

In general, pyogenic abscesses are secondary infections that occur as a result of seeding from other sites, particularly the biliary tree and GI tract. They are often polymicrobial and are caused by a wide variety of organisms. The most commonly implicated organism in North America is Klebsiella pneumoniae.120 Other common pathogens include Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, streptococci, Proteus, Pseudomonas, Bacteroides, and Fusobacterium. Less common, yet noteworthy, pathogens include Aeromonas, Actinomycetes, Nocardia, Salmonella, Haemophilus influenzae, and Yersinia.118–124 Predisposing conditions include diabetes (particularly with Klebsiella-associated abscesses), intraabdominal malignancies, cholangitis, idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease, appendicitis, and diverticulosis.123–126 Tumors, cysts, and infarctions may also become secondarily infected, leading to abscess formation.

Abscesses may be multiple or solitary, and they are more common in the right lobe of the liver.123 Size ranges from microscopic to more than 3 cm in maximum diameter.124 Similar to abscesses in other parts of the body, these consist of central suppurative inflammation and necrosis surrounded by organizing inflammation and fibrosis (Fig. 46.26). The fibrous rind may be quite prominent and may also contain bizarre, reactive fibroblasts and atypical reactive lymphocytes. Granulomatous reactions are occasionally present as well. Nonspecific reactive changes are usually present in the surrounding liver; examples are cholestasis, portal inflammation, ductular proliferation, and venulitis. If the primary site of infection is the biliary tract, changes of acute cholangitis may also be present. Organisms are occasionally detectable with special stains.