CHAPTER 10 Acute Abdominal Pain

Acute abdominal pain is a common complaint that brings patients to emergency departments. As many as 1 in 20 emergency department visits is for abdominal pain.1 Approximately half of these patients have nonspecific findings or “gastroenteritis.”2 The other half have a more serious disorder that warrants further evaluation and treatment. A small proportion of patients has a life-threatening disease. Therefore, the evaluation of acute abdominal pain must be efficient and lead to an accurate diagnosis early in the presentation so that the treatment of patients who are seriously ill is not delayed and patients with self-limited disorders are not overtreated. This chapter discusses the anatomic factors that determine how abdominal pain is perceived, a systematic approach to the evaluation of abdominal pain, and common and special circumstances encountered in evaluating patients with acute abdominal pain.

ANATOMY

Physiologic determinants of pain include the nature of the stimulus, the type of receptor involved, the organization of the neural pathways from the site of injury to the central nervous system, and a complex interaction of modifying influences on the transmission, interpretation, and reaction to pain messages.3,4 Sensory neuroreceptors in abdominal organs are located in the mucosa and muscularis of hollow viscera, on serosal structures such as the peritoneum, and within the mesentery.5 In addition to nociception (the perception of noxious stimuli), sensory neuroreceptors are involved in the regulation of secretion, motility, and blood flow via local and central reflex arcs.6 Although sensory information conveyed in this manner usually is not perceived, disordered regulation of these gastrointestinal functions (secretion, motility, blood flow) can cause pain. For example, patients with irritable bowel syndrome perceive pain as a result of heightened sensitivity of intestinal afferent neurons to normal endogenous stimuli that results in altered gut motility and secretion (see Chapter 118).7

VISCERAL PAIN

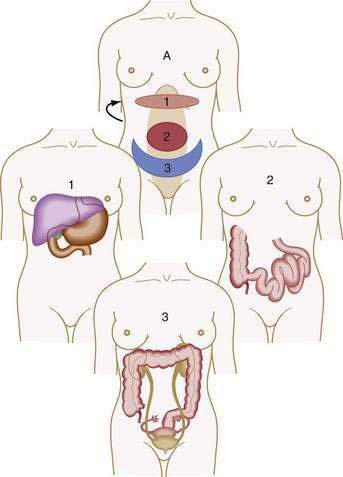

Visceral pain is transmitted by C fibers that are found in muscle, periosteum, mesentery, peritoneum, and viscera. Most painful stimuli from abdominal viscera are conveyed by this type of fiber and tend to be dull, cramping, burning, poorly localized, and more gradual in onset and longer in duration than somatic pain. Because abdominal organs transmit sensory afferents to both sides of the spinal cord, visceral pain is usually perceived to be in the midline, in the epigastrium, periumbilical region, or hypogastrium (Fig. 10-1). Visceral pain is not well localized because the number of nerve endings in viscera is lower than that in highly sensitive organs such as the skin and because the innervation of most viscera is multisegmental. The pain is generally described as cramping, burning, or gnawing. Secondary autonomic effects such as sweating, restlessness, nausea, vomiting, perspiration, and pallor often accompany visceral pain. The patient may move about in an effort to relieve the discomfort.

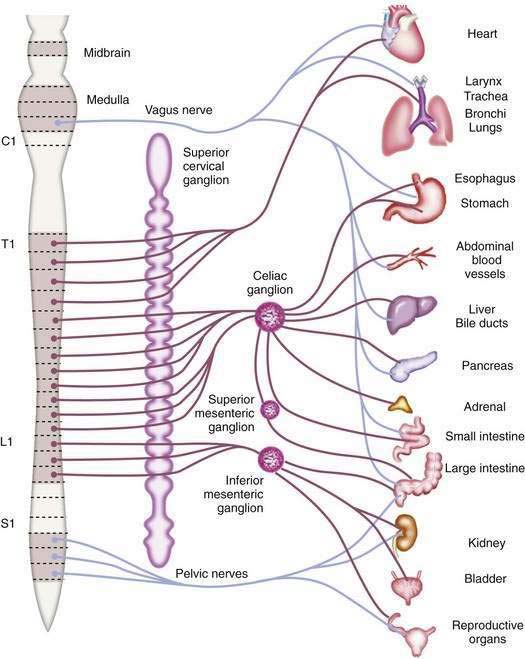

The afferent fibers that mediate painful stimuli from the abdominal viscera follow the distribution of the autonomic nervous system (Fig. 10-2). The cell bodies for these fibers are located in the dorsal root ganglia of spinal afferent nerves. On entering the spinal cord, these fibers branch into the dorsal horn and tract of Lissauer, where afferent nerves from adjacent spinal segments travel in a cephalad direction and caudally over one or two spinal segments before terminating on dorsal horn cells in laminae I and V. The dorsal horn cells within laminae I and V are the primary projection neurons for ascending pain pathways. From the dorsal horn, second-order neurons transmit nociceptive impulses via fibers that pass across the anterior commissure and ascend the spinal cord in the contralateral spinothalamic tract. These fibers project to the thalamic nuclei and the reticular formation nuclei of the pons and medulla. The thalamic nucleus sends third-order neurons to the somatosensory cortex, where the discriminative aspects of pain are perceived. The reticular formation nucleus sends neurons to the limbic system and frontal cortex, where the emotional aspects of pain are interpreted.8,9

Abdominal visceral nociceptors respond to mechanical and chemical stimuli. The principal mechanical signal to which visceral nociceptors are sensitive is stretch; cutting, tearing, or crushing of viscera does not result in pain. Visceral stretch receptors are located in the muscular layers of the hollow viscera, between the muscularis mucosa and submucosa, in the serosa of solid organs, and in the mesentery (especially adjacent to large vessels).5,10 Mechanoreceptor stimulation can result from rapid distention of a hollow viscus (e.g., intestinal obstruction), forceful muscular contractions (e.g., biliary pain or renal colic), and rapid stretching of solid organ serosa or capsule (e.g., hepatic congestion). Similarly, torsion of the mesentery (e.g., cecal volvulus) or tension from traction on the mesentery or mesenteric vessels (e.g., retroperitoneal or pancreatic tumor) results in stimulation of mesenteric stretch receptors.

Abdominal visceral nociceptors also respond to various chemical stimuli. Chemical nociceptors are contained mainly in the mucosa and submucosa of the hollow viscera. These receptors are activated directly by substances released in response to local mechanical injury, inflammation, tissue ischemia and necrosis, and noxious thermal or radiation injury. Such substances include H+ and K+ ions, histamine, serotonin, bradykinin and other vasoactive amines, substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptide, prostaglandins, and leukotrienes.11,12 Accumulation of nociceptor-reactive substances may change the microenvironment of the injured tissue and thereby reduce the pain threshold. The sensation of pain to a given stimulus is thus increased, and otherwise innocuous stimuli become painful. For example, the application of chemical irritants or pressure to normal gastric mucosa is not painful, whereas the application of the same stimuli to inflamed or injured gastric mucosa causes pain.

SOMATIC-PARIETAL PAIN

Somatic-parietal pain is mediated by A-δ fibers that are distributed principally to skin and muscle. Signals from this neural pathway are perceived as sharp, sudden, well-localized pain, such as that which follows an acute injury. These fibers convey pain sensations through spinal nerves. Stimulation of these fibers activates local regulatory reflexes mediated by the enteric nervous system and long spinal reflexes mediated by the autonomic nervous system, in addition to transmitting pain sensation to the central nervous system.13

Reflexive responses, such as involuntary guarding and abdominal rigidity, are mediated by spinal reflex arcs involving somatic-parietal pain pathways. Afferent pain impulses are modified by inhibitory mechanisms at the level of the spinal cord. Somatic A-δ fibers mediate touch, vibration, and proprioception in a dermatomal distribution that matches the visceral innervation of the injured viscera and synapse with inhibitory interneurons of the substantia gelatinosa in the spinal cord. In addition, inhibitory neurons that originate in the mesencephalon, periventricular gray matter, and caudate nucleus descend within the spinal cord to modulate afferent pain pathways. These inhibitory mechanisms allow cerebral influences to modify afferent pain impulses.9,14

REFERRED PAIN

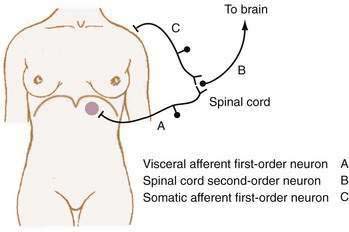

Referred pain is felt in areas remote from the diseased organ and results when visceral afferent neurons and somatic afferent neurons from a different anatomic region converge on second-order neurons in the spinal cord at the same spinal segment. This convergence may result from the innervation, early in embryologic development, of adjacent structures that subsequently migrate away from each other. As such, referred pain can be understood to refer to an earlier developmental state. For example, the central tendon of the diaphragm begins its development in the neck and moves craniocaudad, bringing its innervation, the phrenic nerve, with it.15 Figure 10-3 shows how diaphragmatic irritation from a subphrenic hematoma or splenic rupture may be perceived as shoulder pain (Kehr’s sign).9

CLINICAL EVALUATION

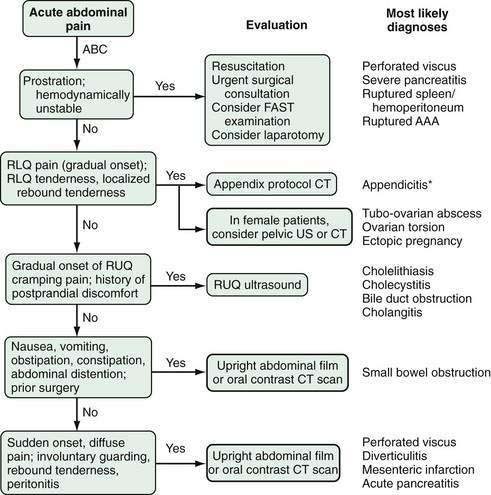

APPROACH TO ACUTE CARE

HISTORY

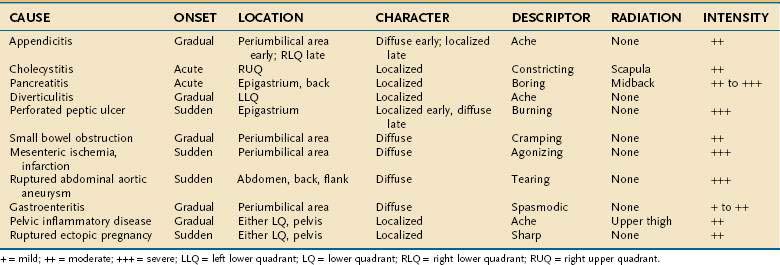

Despite the advances made in clinical imaging, history taking remains the most important component of the initial evaluation of the patient with acute abdominal pain.16 Characteristic features of the pain associated with various common causes of acute abdominal pain are shown in Table 10-1. Attention to these features can lead to a rapid clinical diagnosis or exclusion of important diseases in the differential diagnosis, thus enhancing the reliability and effectiveness of subsequent diagnostic testing.2

Chronology

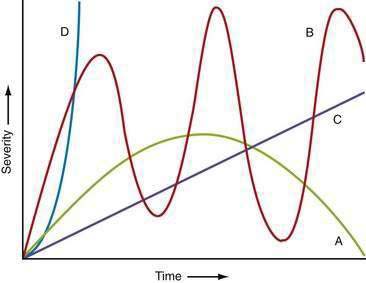

The time courses of several common causes of acute abdominal pain are diagrammed in Figure 10-4. The rapidity of onset of pain is often a measure of the severity of the underlying disorder. Pain that is sudden in onset, severe, and well localized is likely to be the result of an intra-abdominal catastrophe such as a perforated viscus, mesenteric infarction, or ruptured aneurysm. Affected patients usually recall the exact moment of onset of their pain. Progression is an important temporal factor in abdominal pain. In some disorders, such as gastroenteritis, pain is self-limited, whereas in others, such as appendicitis, pain is progressive. Colicky pain has a crescendo-decrescendo pattern that may be diagnostic, as in renal colic. The duration of abdominal pain is also important. Patients who seek evaluation of abdominal pain that has been present for an extended period (e.g., weeks) are less likely to have an acute life-threatening illness than patients who present within hours to days of the onset of their symptoms.

Location

The location of abdominal pain provides a clue to interpreting the cause. As noted, a given noxious stimulus may result in a combination of visceral, somatic-parietal, and referred pain, thereby creating confusion in interpretation unless the neuroanatomic pathways are considered. For example, the pain of diaphragmatic irritation from a left-sided subphrenic abscess may be referred to the shoulder and misinterpreted as pain from ischemic heart disease (see Fig. 10-3). Changes in location may represent progression from visceral to parietal irritation, as with appendicitis, or represent the development of diffuse peritoneal irritation, as with a perforated ulcer.

IMAGING STUDIES

Computed Tomography

The development of high-speed helical computed tomography (CT) scanning has revolutionized the evaluation of acute abdominal pain. In many conditions, such as appendicitis, CT scanning can almost eliminate diagnostic uncertainty. In the pre-CT era, history taking and physical examination alone had a specificity of approximately 80%; by contrast, the sensitivity and specificity of CT scanning for acute appendicitis are 94% and 95%, respectively.17 A negative CT scan in the setting of acute abdominal pain has considerable value in excluding common disorders.

A final consideration regarding the role of CT in the evaluation of acute abdominal pain is radiation exposure. Particularly for patients younger than 35 years and those who have required multiple examinations, abdominal CT may increase the lifetime risk of cancer.18 Additionally, unless a life-threatening condition is suspected, CT is best avoided in a pregnant patient, in whom ultrasound examination or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may provide a suitable alternative.

Ultrasonography

A FAST is a rapid, reliable, bedside test to detect fluid in the abdominal cavity. Although its main usefulness is for the evaluation of injured persons, this examination also aids in the diagnosis of any condition that results in free intraperitoneal fluid. Although not part of the formal FAST series, imaging of the aorta can be added, allowing a rapid assessment for aortic aneurysm. General beside ultrasound is likely to be used increasingly by nonradiologists in the future. A Swedish study has demonstrated that the diagnostic accuracy of emergency abdominal examinations by surgeons is increased significantly when an ultrasound examination is added to the evaluation.19

CAUSES

Acute abdominal pain is usually defined as pain of less than one week in duration. Patients usually seek attention within the first 24 to 48 hours, although some may endure longer periods of abdominal discomfort. The most common reason for a patient to seek emergency department evaluation of abdominal pain is so-called nonspecific abdominal pain. Between 25% and 50% of all patients who visit an emergency department for abdominal pain will have no specific disease identified. The distribution of the causes of abdominal pain in patients who present to an emergency department is shown in Table 10-2.

Table 10-2 Causes of Acute Abdominal Pain in Patients Presenting to an Emergency Department

| CAUSE | PATIENTS (%) |

|---|---|

| Nonspecific abdominal pain | 35 |

| Appendicitis | 17 |

| Bowel obstruction | 15 |

| Urologic disease | 6 |

| Biliary disease | 5 |

| Diverticular disease | 4 |

| Pancreatitis | 2 |

| Medical illness | 1 |

| Other | 15 |

From Irvin TT. Causes of abdominal pain in 1190 patients admitted to a British Surgical Service. Br J Surg 1989; 76:1121-5.

ACUTE APPENDICITIS

Acute appendicitis is a ubiquitous problem. In adult patients younger than 60 years, acute appendicitis accounts for 25% of admissions to the hospital from the emergency department for abdominal pain.20 The overall incidence of appendicitis is approximately 11/10,000 population, with a lifetime risk of 8.6% for men and 6.7% for women.21 Typically, acute appendicitis begins with prodromal symptoms of anorexia, nausea, and vague periumbilical pain. Within 6 to 8 hours, the pain migrates to the right lower quadrant and peritoneal signs develop. In uncomplicated appendicitis, a low-grade fever to 38°C and mild leukocytosis are usually present. A higher temperature and white blood cell count are associated with perforation and abscess formation. The mnemonic PANT can help the novice remember the classic progression of symptoms in appendicitis—pain followed by anorexia followed by nausea followed by temperature elevation. Uncommon presentations of acute appendicitis, however, are common, and the wary physician will not reject a diagnosis of acute appendicitis simply on the basis of the patient’s history and physical examination alone. Whereas plain abdominal radiographs are not diagnostic and have little role in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis, CT has dramatically improved the accuracy of diagnosis in patients with acute appendicitis. The finding of an appendiceal diameter larger than 6 mm has positive and negative predictive values of 98%.22 Other CT signs of acute appendicitis include periappendiceal fat inflammation, presence of fluid in the right lower quadrant, and failure of contrast dye to fill the appendix23; these findings have lower degrees of specificity. Traditionally, an erroneous diagnosis of appendicitis, reflected by the finding of normal pathology at surgical exploration, was as high as 33%.24 The addition of CT has reduced the false-negative rate to approximately 6% for men and 10% for women.25 As noted earlier, CT does entail radiation exposure,18 and some authorities advocate avoiding CT in children and adolescents,26 in whom a higher degree of diagnostic uncertainty is tolerated in favor of lower radiation exposure (see Chapter 116).

ACUTE BILIARY DISEASE

Biliary disease accounts for approximately 5% to 7% of emergency department visits for abdominal pain.2,20 Most patients in this group present at some point on the spectrum between biliary pain and acute cholecystitis. Biliary pain is a syndrome of right upper quadrant or epigastric pain, usually postprandial, caused by transient obstruction of the cystic duct by a gallstone. Biliary pain is self-limited, generally lasting less than 6 hours. Acute cholecystitis is, in most cases, caused by persistent obstruction of the cystic duct by a gallstone. The pain of acute cholecystitis is almost indistinguishable from that of biliary pain, except that it is persistent. The pain usually is a dull ache and is localized to the right upper quadrant or epigastrium and may radiate around the back to the right scapula. Nausea, vomiting, and low-grade fever are common. On examination, right upper quadrant tenderness, guarding, and Murphy’s sign (inspiratory arrest on palpation of the right upper quadrant) are diagnostic of acute cholecystitis. The white blood cell count is usually mildly elevated but may be normal. Mild elevations in serum total bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase levels are typical. The role of gallstones in the etiology of biliary pain and acute cholecystitis makes ultrasound evaluation of the right upper quadrant the key diagnostic test. Demonstration of gallstones may suggest biliary pain, whereas the finding of stones with gallbladder wall thickening, pericholecystic fluid, and pain on compression of the gallbladder with the ultrasound probe (sonographic Murphy’s sign) is essentially diagnostic of acute cholecystitis, as is positive hepatobiliary scintigraphy (e.g., HIDA scan).27 Patients with acute cholecystitis are best managed with cholecystectomy within 48 hours.28–30 Patients who are diabetic, particularly those with a leukocyte count over 15,000/mm3, are at particular risk for gangrenous cholecystitis and should have immediate surgical consultation.31 These patients are likely to require an emergent open cholecystectomy.

Patients who present with right upper quadrant pain with jaundice and signs of sepsis should be suspected of having obstruction of the bile duct by a gallstone. Right upper quadrant pain, fever and chills, and jaundice (Charcot’s triad) are suggestive of ascending cholangitis.32 These patients require intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and bile duct drainage, usually by endoscopy (see also Chapters 65, 66, and 67).

SMALL BOWEL OBSTRUCTION

Intestinal obstruction may occur in patients of all ages. In pediatric patients, intussusception, intestinal atresia, and meconium ileus are the most common causes. In adults, about 70% of cases are caused by postoperative adhesions; incarcerated hernias make up most of the remainder. Small bowel obstruction is characterized by sudden, sharp, periumbilical abdominal pain. Nausea and vomiting occur soon after the onset of pain and provide temporary relief of discomfort. Frequent bilious emesis with epigastric pain is suggestive of high (proximal) intestinal obstruction, whereas cramping periumbilical pain with infrequent feculent emesis is more typical of distal intestinal obstruction. Examination reveals an acutely ill, restless patient. Fever, tachycardia, and orthostatic hypotension are common. Abdominal distention is usual. Auscultation characteristically demonstrates hyperactive bowel sounds and audible rushes. The patient’s abdomen is diffusely tender to percussion and palpation, but peritoneal signs are absent, unless a complication such as ischemia or perforation has occurred. Leukocytosis and lactic acidosis suggest intestinal ischemia or infarction. Plain radiographs of the abdomen are diagnostic when they reveal dilated loops of small intestine with air-fluid levels and decompressed distal small bowel and colon. Plain abdominal films can be misleading in a patient with proximal jejunal obstruction, because dilated bowel loops and air-fluid levels may be absent. CT is superior for establishing the diagnosis and location of intestinal obstruction.33 In patients with partial small intestinal obstruction, initial treatment is with bowel rest, intravenous fluids, nasogastric decompression, and close observation. Surgery is required for patients who fail conservative management or have evidence of complete obstruction, especially if ischemia is suspected (see also Chapter 119).

ACUTE DIVERTICULITIS

Acute diverticulitis is a common disease. Approximately 80% of affected patients are older than 50 years,34 but the incidence may be increasing in younger persons.35 Patients with diverticulitis usually present with constant, dull, left lower quadrant pain and fever. They may complain of constipation or obstipation and usually are found to have a leukocytosis. Physical examination demonstrates left lower quadrant tenderness and, in some cases, a left lower quadrant mass. Localized peritoneal signs are frequent. In severe cases, generalized peritonitis may be present, making differentiation from other causes of a perforated viscus difficult. CT is reliable in confirming the diagnosis, with a sensitivity of 97%,36 and should be performed routinely in the emergency evaluation of patients with diverticulitis.

Acute diverticulitis presents as a spectrum of disease from mild abdominal discomfort to gross fecal peritonitis, which is an acute surgical emergency. The severity of diverticulitis, as determined by CT, is best described using the Hinchey grading system (see Table 117-2).37 Patients with mild disease and no CT findings of perforation, in the absence of limiting comorbid disease, can generally be treated as an outpatient. Those with Hinchey grade I diverticulitis (localized pericolic abscess or inflammation) frequently require hospitalization for intravenous antibiotics. Patients with Hinchey grade II diverticulitis (pelvic, intra-abdominal, or retroperitoneal abscess) should undergo CT-guided drainage of the abscess and receive a course of broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics. Patients with Hinchey III (generalized purulent peritonitis) and IV (generalized fecal peritonitis) diverticulitis frequently require emergency surgery. Optimal surgical management of patients with Hinchey I or II diverticulitis is a matter of debate (see Chapter 117).

ACUTE PANCREATITIS

Hospital admissions for acute pancreatitis in the United States seem to be increasing. The incidence of acute pancreatitis in California rose from 33 to 43 cases/100,000 between 1994 and 2001.38 Acute pancreatitis typically begins as acute pain in the epigastrium that is constant, unrelenting, and frequently described as boring through to the back or left scapular region. Fever, anorexia, nausea, and vomiting are typical. Patients with pancreatitis usually are more comfortable sitting upright, leaning forward slightly, and are commonly found in this position in the emergency department. Physical examination reveals an acutely ill patient in considerable distress. Patients are usually tachycardic and tachypneic. Abdominal examination reveals hypoactive bowel sounds and marked tenderness to percussion and palpation in the epigastrium. Abdominal rigidity is a variable finding. In rare patients, flank or periumbilical ecchymoses (Grey-Turner’s or Cullen’s sign, respectively) develop in the setting of pancreatic necrosis with hemorrhage. Extremities are often cool and cyanotic, reflecting underperfusion. White blood cell counts of 12,000 to 20,000/mm3 are common. Elevated serum and urine amylase levels are usually present within the first few hours of pain. Depending on the cause and severity of pancreatitis, serum electrolyte, calcium, and blood glucose levels and liver biochemical test and arterial blood gas results may be abnormal. Abdominal ultrasonography is useful for identifying gallstones as a potential cause of pancreatitis. CT is reserved for patients with severe or complicated pancreatitis.

Although most cases of acute pancreatitis are self-limited, as many as 20% of patients have severe disease with local or systemic complications,39 including hypovolemia and shock, renal failure, liver failure, and hypocalcemia. Although a number of prognostic physiologic scales, such as the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) and Acute Physiologic Assessment and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II scores, have been advocated as measures of the severity of acute pancreatitis, the Ranson score, first published in 1974, remains a useful and widely used checklist for the early assessment of patients with acute pancreatitis.40 The Ranson score consists of five early and six late factors that indicate severe pancreatitis (see Table 58-2). A minority of patients with severe acute pancreatitis present with a profound intra-abdominal catastrophe, usually caused by thrombosis of the middle colic artery or right colic artery, which travels in proximity to the head of the pancreas, with resulting colonic infarction. This process may not be seen clearly on CT scans obtained early in the course of disease and should be suspected in any case marked by rapid hemodynamic collapse. Such patients require immediate laparotomy (see Chapter 58).

PERFORATED PEPTIC ULCER

The epidemiology of peptic ulcer disease continues to change. The overall incidence of peptic ulcer disease has declined significantly since the late 1970s,41,42 and the number of patients requiring hospital admission for severe and complicated peptic ulcer disease has also decreased.42 Better therapeutic modalities, including proton pump inhibitors, eradication of Helicobacter pylori, and endoscopic methods for control of hemorrhage, have reduced the number of patients with peptic ulcer disease who require surgical intervention,43 although the incidence of complicated disease has increased in older adults, in whom morbidity and mortality related to surgery are also increased.42

A perforated peptic ulcer should be suspected in any patient with the sudden onset of severe abdominal pain who presents with abdominal rigidity and free intraperitoneal air. Pneumoperitoneum is identified on an abdominal radiograph in 75% of patients (Fig. 10-6). In equivocal cases, CT of the abdomen usually suggests the diagnosis by demonstrating edema in the region of the gastric antrum and duodenum, associated with extraluminal air. CT may not be diagnostic, however, and patients with diffuse peritonitis or hemodynamic collapse should be explored surgically. Laparotomy is acceptable as the primary diagnostic maneuver in such patients. Endoscopy is not advisable when the diagnosis of a perforated peptic ulcer is suspected. Insufflation of the stomach can convert a sealed perforation into a free perforation. Survival following emergency surgery for complications of peptic ulcer disease is surprisingly poor. Patients who require surgery for a complication of peptic ulcer disease are generally older and more medically ill than those seen in the past. Sarosi and colleagues have reported a 23% in-hospital mortality rate in a Veterans Administration population,44 and Imhof and associates,45 reporting on a series of German patients with perforated peptic ulcer, found an in-hospital mortality rate of 12.1%, a one-year mortality rate of 28.7%, and a five-year mortality rate of 46.8% (see also Chapters 52 and 53).

ACUTE MESENTERIC ISCHEMIA

Acute mesenteric ischemia can result from occlusion of a mesenteric vessel arising from an embolus, which may emanate from an atheroma of the aorta or cardiac mural thrombus, or from primary thrombosis of a mesenteric vessel, usually at a site of atherosclerotic stenosis. Embolic occlusion is more common in the superior mesenteric artery than the celiac or inferior mesenteric artery, presumably because of the less acute angle of the superior mesenteric artery off the abdominal aorta. Nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia results from inadequate visceral perfusion and can also lead to intestinal ischemia and infarction. Such cases are usually consequent to catastrophic systemic illnesses such as cardiogenic or septic shock. Acute mesenteric embolism, mesenteric thrombosis, and nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia each account for approximately one third of cases of acute mesenteric ischemia and have a combined mortality rate of 60% to 100%.46

CT is the best initial diagnostic test. Mesenteric angiography may be useful for determining the cause of intestinal ischemia and defining the extent of vascular disease. Patients with acute embolic or thrombotic intestinal ischemia should be referred for immediate revascularization and bowel resection.47 Patients with nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia are best managed by treatment of the underlying shock state. For those with persistent symptoms, laparotomy for resection of infarcted intestine may be necessary. Transcatheter vasodilator therapy may be helpful for patients who are found to have vasospasm on visceral arteriography (see also Chapter 114).47

ABDOMINAL AORTIC ANEURYSM

Rupture of an abdominal aortic aneurysm is heralded by the sudden onset of acute, severe abdominal pain localized to the midabdomen or paravertebral or flank areas. The pain is tearing in nature and associated with prostration, lightheadedness, and diaphoresis. If the patient survives transit to the hospital, shock is the most common presentation. Physical examination reveals a pulsatile, tender abdominal mass in about 90% of cases. The classic triad of hypotension, a pulsatile mass, and abdominal pain is present in 75% of cases and mandates immediate surgical intervention.47

ABDOMINAL COMPARTMENT SYNDROME

Although not usually presenting as acute abdominal pain, abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) warrants consideration in any patient with an abdominal emergency. First reported in the setting of massive intra-abdominal trauma, ACS, defined as pathologic elevation of intra-abdominal pressure, is now recognized as a frequent complication of many severe disease processes. An elevated intra-abdominal pressure may develop in a patient who survives massive volume resuscitation with resulting visceral edema or who has a disease such as severe pancreatitis that can cause visceral or retroperitoneal edema. The elevated intra-abdominal pressure in turn compromises visceral perfusion, with resulting injury and additional edema. The kidney is particularly prone to underperfusion in this setting, and kidney failure may be the first sign of ACS.48

Intra-abdominal pressure can be measured simply by connecting a transducer to a urinary catheter, with the zero reference point at the midaxillary line in a supine patient. The World Society for Abdominal Compartment Syndrome has established a consensus grading scheme for ACS based on the measured bladder pressure. A normal value for bladder pressure is less than 7 mm Hg. Grade I ACS is defined as a pressure of 12 to 15 mm Hg, grade II as 16 to 20 mm Hg, grade III as 21 to 25 mm Hg, and grade IV as greater than 25 mm Hg. Nonsurgical options for treating low-grade ACS include gastric decompression, sedation, neuromuscular blockade, placing the patient in a reverse Trendelenburg position while allowing the hips to remain in a neutral position, and diuretics. In a patient with high-grade ACS, particularly when renal and respiratory function is compromised, laparotomy and creation of an open abdomen is most effective. Management of the open abdomen requires specific surgical expertise usually found in referral medical centers.49

OTHER INTRA-ABDOMINAL CAUSES

Other intra-abdominal causes of acute abdominal pain include the following: gynecologic conditions such as endometritis, acute salpingitis with or without tubo-ovarian abscess, ovarian cysts or torsion, and ectopic pregnancy; spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (Chapter 91); functional dyspepsia and peptic ulcer disease (Chapters 13 and 52); infectious gastroenteritis (Chapters 107 and 108); viral hepatitis and other liver infections (Chapters 77 to 82); pyelonephritis; cystitis; mesenteric lymphadenitis; inflammatory bowel disease (Chapters 111 and 112); and functional abnormalities such as irritable bowel syndrome (Chapter 118) and intestinal pseudo-obstruction (Chapter 120).

EXTRA-ABDOMINAL CAUSES

Acute abdominal pain may arise from disorders involving extra-abdominal organs and systemic illnesses. Examples are listed in Table 10-3. Surgical intervention for patients with acute abdominal pain arising from an extra-abdominal or systemic illness is seldom required except in cases of pneumothorax, empyema, and esophageal perforation. Esophageal perforation may be iatrogenic, result from blunt or penetrating trauma, or occur spontaneously (Boerhaave’s syndrome; see also Chapter 45).

SPECIAL CIRCUMSTANCES

Pregnancy

Surgery in pregnancy is not rare; approximately 1 in 500 pregnancies will be associated with a nonobstetric general surgical intervention.50 Primary consideration is given to the health of the mother. The middle three months of gestation are optimal for abdominal surgical intervention, because this period presents the lowest risk for teratogenicity and spontaneous labor. Emergency interventions during pregnancy carry a risk of fetal loss that varies with the type of intervention and the age of gestation.

Appendicitis occurs in approximately 1 in 2000 pregnancies and is equally distributed among the three trimesters. In later stages of pregnancy, the appendix may be displaced cephalad, with consequent displacement of the signs of peritoneal irritation away from McBurney’s point. Ultrasound or, in challenging cases, MRI may be useful for establishing a diagnosis in this setting. Biliary tract disease is also common during pregnancy. Open or laparoscopic management of these diseases is safe but is associated with a rate of preterm delivery of approximately 12% for appendectomy and 11% for cholecystectomy.51

Immunocompromised Hosts

In addition to diseases that occur in the general population, such as appendicitis and cholecystitis, a number of diseases unique to immunocompromised hosts may manifest with acute abdominal pain, including neutropenic enterocolitis, drug-induced pancreatitis, graft-versus-host disease, pneumatosis intestinalis, and cytomegalovirus (CMV) and fungal infections. Patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can present a particular challenge. When advanced, HIV infection is associated with a number of other diseases that may present as acute abdominal pain. One of the most common abdominal disorders seen in immunocompromised persons in the developing world is primary peritonitis. Affected patients have suppurative peritonitis without a definable source. Spontaneous intestinal perforation, usually secondary to CMV infection, is also common in patients with advanced HIV infection. Tuberculous peritonitis is a consideration in patients from areas in which tuberculosis is common.52 In general, immunocompromised patients may lack the definitive signs of an acute abdominal crisis usually seen in immunocompetent persons; an elevated temperature, peritoneal signs, and leukocytosis may be absent in these cases.

PHARMACOLOGIC MANAGEMENT

An unfortunate practice in the care of patients with acute abdominal pain is the delay in administration of narcotics pending definitive surgical assessment. Sir Zachary Cope stated that “Morphine does little or nothing to stop serious intra-abdominal disease, but it puts an efficient screen in front of the symptoms.”53 The practice of delaying relief of pain in a suffering patient, however, does not appear to withstand careful clinical scrutiny. Six studies in which the early administration of analgesia was compared with administration of placebo in patients with acute abdominal pain have shown that the patients who receive analgesics are more comfortable and do not experience a delay in diagnosis.54 Patients with acute abdominal pain frequently are suffering the most intense pain that they have ever experienced and should receive appropriate opioid analgesics early in their care.

Patients with acute abdominal processes frequently require antibiotic treatment for peritonitis. When appropriate, antibiotic therapy aimed at the likely causative pathogens should be given as soon as a putative diagnosis is reached; little benefit is derived from treating an immunocompetent patient with broad-spectrum antibiotics before a likely source is identified. Patients who are immunocompromised or neutropenic are an exception to this rule. They should receive broad-spectrum antibiotics early in the course of management for acute abdominal pain (see Chapters 37 and 91).

An G, West M. Abdominal compartment syndrome: A concise clinical review. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1304-10. (Ref 49.)

Addiss DG, Shaffer N, Fowler B, Tauxe RV. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132:910-25. (Ref 21.)

Birnbaum BA, Wilson SR. Appendicitis at the millennium. Radiology. 2000;215:337-48. (Ref 23.)

Bohner H, Yang Q, Franke C, et al. Simple data from history and physical examination help to exclude bowel obstruction and to avoid radiographic studies in patients with acute abdominal pain. Eur J Surg. 1998;164:777-84. (Ref 2.)

Cotton M. The acute abdomen and HIV. Trop Doct. 2006;36:198-200. (Ref 52.)

Diaz JJ, Bokhari F, Mowery NT, et al. Guidelines for management of small bowel obstruction. J Trauma. 2008;64:1651-64. (Ref 33.)

Frossard JL, Steer ML, Pastor CM. Acute pancreatitis. Lancet. 2008;371:143-52. (Ref 39.)

Jacobs DO. Diverticulitis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2057-66. (Ref 34.)

Maerz L, Kaplan LJ. Abdominal compartment syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:S212-15. (Ref 48.)

Manterola C, Asutdillo P, Losada H, et al. Analgesia in patients with acute abdominal pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; (3):CD005660. (Ref 54.)

McGory ML, Zingmond DS, Nanayakkara D, et al. Negative appendectomy rate: Influence of CT scans. Am Surg. 2005;71:803-8. (Ref 25.)

Parangi S, Levine D, Henry A, et al. Surgical gastrointestinal disorders during pregnancy. Am J Surg. 2007;193:223-32. (Ref 50.)

Peng WK, Sheikh Z, Nixon SJ, Paterson-Brown S. Role of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the early management of acute gallbladder disease. Br J Surg. 2005;92:586-91. (Ref 30.)

Silen W. Cope’s early diagnosis of the acute abdomen, 18th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1991. p 301. (Ref 16.)

Terasawa T, Blackmore CC, Brent S, Kohlwes RJ. Systematic review: Computed tomography and ultrasonography to detect acute appendicitis in adults and adolescents. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:537-46. (Ref 17.)

1. Brewer RJ, Golden GT, Hitch DC, et al. Abdominal pain: An analysis of 1,000 consecutive cases in a university hospital emergency room. Am J Surg. 1976;131:219-23.

2. Bohner H, Yang Q, Franke C, et al. Simple data from history and physical examination help to exclude bowel obstruction and to avoid radiographic studies in patients with acute abdominal pain. Eur J Surg. 1998;164:777-84.

3. Melzack R, Wall PD. Pain mechanisms: A new theory. Science. 1965;150:971-9.

4. Melzack R, Torgerson WS. On the language of pain. Anesthesiology. 1971;34:50-9.

5. Leek B. Abdominal visceral receptors. In: Neil E, editor. Enteroceptors. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1972:113.

6. Gershon M, Kirchgessner A, Wade P. Functional anatomy of the enteric nervous system. In: Johnson LR, editor. Physiology of the gastrointestinal tract. New York: Raven Press; 1994:381.

7. Mayer EA, Raybould HE. Role of visceral afferent mechanisms in functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:1688-704.

8. Cervero F. Somatic and visceral sensory integration in the thoracic spinal cord. In: Cervero F, Morrison JFB, editors. Visceral sensation. New York: Elsevier; 1986:189.

9. Fields HL. Pain. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1987.

10. Janig W, Morrison JFB. Functional properties of spinal visceral afferents supplying abdominal and pelvic organs, with special emphasis on visceral nociception. In: Cervero F, Morrison JFB, editors. Visceral sensation. New York: Elsevier; 1986:87.

11. Bonica J. The Management of Pain. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1990.

12. Higashi H. Pharmacological aspects of visceral sensory receptors. In: Cervero F, Morrison JFB, editors. Visceral sensation. New York: Elsevier; 1986:21.

13. Sengupta JN, Gebhart GF. Gastrointestinal afferent fibers and sensation. In: Johnson LR, editor. Physiology of the gastrointestinal tract. New York: Raven Press; 1994:483.

14. Basbaum AI, Fields HL. Endogenous pain control systems: Brainstem spinal pathways and endrophin circuitry. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1984;7:309-38.

15. Ryan S, Folan-Curran J. Embryology and anatomy of the neonatal chest. In: Donoghue V, Baert AL, editors. Radiological imaging of the neonatal chest. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2002:195.

16. Silen W. Cope’s early diagnosis of the acute abdomen, 18th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1991. p 301

17. Terasawa T, Blackmore CC, Brent S, Kohlwes RJ. Systematic review: Computed tomography and ultrasonography to detect acute appendicitis in adults and adolescents. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:537-46.

18. Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. Computed tomography—an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2277-84.

19. Lindelius A, Torgren S, Sonden A, et al. Impact of surgeon-performed ultrasound on diagnosis of abdominal pain. Emerg Med J. 2008;25:486-91.

20. Irvin TT. Abdominal pain: A surgical audit of 1190 emergency admissions. Br J Surg. 1989;76:1121-5.

21. Addiss DG, Shaffer N, Fowler B, Tauxe RV. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132:910-25.

22. Kessler N, Cyteval C, Gallix B, et al. Appendicitis: Evaluation of sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of US, Doppler US, and laboratory findings. Radiology. 2004;230:472-8.

23. Birnbaum BA, Wilson SR. Appendicitis at the millennium. Radiology. 2000;215:337-48.

24. Yap ET. A five-year survey of acute appendicitis. Am J Surg. 1958;95:849-52.

25. McGory ML, Zingmond DS, Nanayakkara D, et al. Negative appendectomy rate: Influence of CT scans. Am Surg. 2005;71:803-8.

26. Slovis T, Bedron W. Panel discussion. Pediatr Radiol. 2002;32:242-4.

27. Ralls PW, Colletti PM, Lapin SA, et al. Real-time sonography in suspected acute cholecystitis. Prospective evaluation of primary and secondary signs. Radiology. 1985;155:767-71.

28. Lo CM, Liu CL, Fan ST, et al. Prospective randomized study of early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute xholecystitis. Ann Surg. 1998;227:461-7.

29. Low JK, Barrow P, Owera A, Ammori BJ. Timing of laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: Evidence to support a proposal for an early interval surgery. Am Surg. 2007;73:1188-92.

30. Peng WK, Sheikh Z, Nixon SJ, Paterson-Brown S. Role of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the early management of acute gallbladder disease. Br J Surg. 2005;92:586-91.

31. Fagan SP, Awad SS, Rahwan K, et al. Prognostic factors for the development of gangrenous cholecystitis. Am J Surg. 2003;186:481-5.

32. Wada K, Takada T, Kawarada Y, et al. Diagnostic criteria and severity assessment of acute cholangitis: Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:52-8.

33. Diaz JJ, Bokhari F, Mowery NT, et al. Guidelines for management of small bowel obstruction. J Trauma. 2008;64:1651-64.

34. Jacobs DO. Diverticulitis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2057-66.

35. Konvolinka CW. Acute diverticulitis under age forty. Am J Surg. 1994;167:562-5.

36. Ambrosetti P, Grossholz M, Becker C, et al. Computed tomography in acute left colonic diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 1997;84:532-4.

37. Lohrmann C, Ghanem N, Pache G, et al. CT in acute perforated sigmoid diverticulitis. Eur J Radiol. 2005;56:78-83.

38. Frey CF, Zhou H, Harvey D, White RH. The incidence and case-fatality rates of acute biliary, alcoholic, and idiopathic pancreatitis in California, 1994-2001. Pancreas. 2006;33:336-44.

39. Frossard JL, Steer ML, Pastor CM. Acute pancreatitis. Lancet. 2008;371:143-52.

40. Ranson JH, Rifkin KM, Roses DF, et al. Prognostic signs and the role of operative management in acute pancreatitis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1974;139:69-81.

41. Gustavsson S, Kelly KA, Melton LJ, Zinsmeister AR. Trends in peptic ulcer surgery. A population-based study in Rochester, Minnesota, 1956-1985. Gastroenterology. 1988;94:688-94.

42. Shiotani A, Graham D. Pathogenesis and therapy of gastric and duodenal ulcer disease. Med Clin North Am. 2002;86:1447-66.

43. Towfigh S, Chandler C, Hines OJ, McFadden DW. Outcomes from peptic ulcer surgery have not benefited from advances in medical therapy. Am Surg. 2002;68:385-9.

44. Sarosi GA, Jaiswal KR, Nwariaku FE, et al. Surgical therapy of peptic ulcers in the 21st century: More common than you think. Am J Surg. 2005;190:775-9.

45. Imhof M, Epstein S, Ohmann C, Roher HD. Poor late prognosis of bleeding peptic ulcer. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2007;392:587-91.

46. Chang RW, Chang JB, Longo WE. Update in management of mesenteric ischemia. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3243-7.

47. Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 practice guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease. Circulation. 2006;113:e463-5.

48. Maerz L, Kaplan LJ. Abdominal compartment syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:S212-S15.

49. An G, West M. Abdominal compartment syndrome: A concise clinical review. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1304-10.

50. Parangi S, Levine D, Henry A, et al. Surgical gastrointestinal disorders during pregnancy. Am J Surg. 2007;193:223-32.

51. Affleck DG, Hadrahan DL, Egger MJ, Price RR. The laparoscopic management of appendicitis and cholelithiasis during pregnancy. Am J Surg. 1999;178:523-8.

52. Cotton M. The acute abdomen and HIV. Trop Doct. 2006;36:198-200.

53. Cope Z. The early diagnosis of the acute abdomen, 10th ed. London: Oxford University Press; 1951. p 270

54. Manterola C, Asutdillo P, Losada H, et al. Analgesia in patients with acute abdominal pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; (3):CD005660.