Acute Abdomen in the Pediatric Intensive Care Patient 7

Gastrointestinal Atresia and Stenosis

Congenital Megacolon (Hirschsprung Disease)

M. Hoermann

The differential diagnosis of diseases that present with an “acute abdomen” in children is very broad and varies with the age of the patient (Table 7.1). Acute abdominal pain is one of the most frequent indications for radio-graphic examinations in children. Diseases of the gastrointestinal tract are the leading cause, but extra-abdominal diseases such as basal pneumonia may also underlie an acute abdomen. Moreover, it is sometimes difficult in children to distinguish somatic pain from pain due to a psychosocial conflict. The limited ability of these young patients to cooperate and communicate makes it difficult to take an accurate history and conduct a radiologic evaluation.

This chapter deals with the differential diagnosis and imaging of an acute abdomen that may occur in pediatric intensive care patients, may prompt admission to an intensive care unit, or may require evaluation by a radiologist in an acute emergency.

Abdominal emergencies in school-age children show a broad overlap with diseases and findings in adults, and so the discussions in this chapter will be limited to diseases in neonates and small children.

Examination Technique

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography is the primary imaging modality for evaluating an acute abdomen in children, even after trauma. Ultrasound scans have replaced plain abdominal radiographs and contrast examinations in many cases. A basic rule is the smaller the patient, the higher the operating frequency of the ultrasound transducer (Table 7.2).

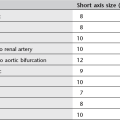

Plain Abdominal Radiograph

Upright abdominal radiographs are poorly tolerated by most small children and tend to be of poorer quality than comparable supine radiographs. On the whole, however, plain films of an acute abdomen are nonspecific and may contribute little to making a diagnosis. Given these limitations, strict criteria should be applied in selecting children for plain abdominal radiographs (Table 7.3).

|

Neonates |

Infants and small children |

School-age children |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Age |

GI tract |

Parenchymal organs |

|

Newborn |

12–15 MHz |

10–12 MHz |

|

Small child |

12–15 MHz |

7 MHz |

|

School-age child |

10–12 MHz |

5–7 MHz |

Coverage should always include the basal lung zones and inguinal region so that basal pneumonia or an incarcerated hernia can be recognized. If free air is suspected, a chest radiograph should be obtained in the upright or cross-table supine position (see Figs. 7.5b and 7.6b).

Oral Contrast Examinations

Contrast examinations of the gastrointestinal tract are rarely necessary. The contrast medium may consist of barium or a nonionic water-soluble material.

Gastrografin should not be used in children, as its hyperosmolarity may lead to life-threatening dehydration and cause toxic injury to the gastrointestinal mucosa in neonates.

Meconium Ileus

Meconium ileus is the initial manifestation of cystic fibrosis in ca. 15% of affected newborns. The inspissation of bowel contents due to abnormal intestinal secretions prevents the normal passage of meconium.

Imaging

The plain abdominal radiograph shows signs of a low obstruction as in atresia or stenosis but without significant prestenotic dilatation. Air–fluid levels are very rarely seen owing to the inspissated condition of the meconium. The viscous meconium sometimes contains small air bubbles. This may suggest the correct diagnosis but is nonspecific, as it may also result from a distal obstruction due to other causes.

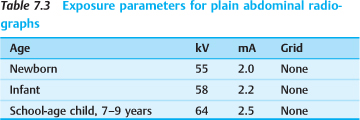

The contrast enema is both therapeutic and diagnostic and demonstrates a poorly distensible microcolon (“unused colon,” Fig. 7.1). When contrast medium enters the terminal ileum, the radiograph shows irregular filling defects caused by inspissated meconium.

Therapeutic contrast enema with a hypertonic medium is successful in up to 60% of cases. Attention must be given to avoiding perforations (up to 5% of cases) and to the maintenance of fluid balance.

Complications

Calcifications in the abdominal radiograph suggest an intrauterine perforation, possibly associated with pseudocyst formation, as a possible complication of meconium ileus. Other potential complications are volvulus and atresia.

Fig. 7.1 Meconium ileus with a nondistensible “microcolon” and dilatation of the small bowel.

Necrotizing Enterocolitis

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) occurs in immature newborns (> 90% of NEC patients are delivered before 35 weeks’ gestation) several days after the start of enteral feeding; symptoms never appear before feeding is initiated. Very rarely, NEC may also occur in mature newborns. The etiology is uncertain, but NEC has a multifactorial pathogenesis based on damage to the mucosal barrier.

Sites of predilection for NEC are the terminal ileum and ascending colon, although radiographic changes are often first noted in the sigmoid colon.

Diagnostic Strategy

NEC is a clinical diagnosis. The primary imaging modality is plain abdominal radiography.

Ultrasonography is being used increasingly in the diagnosis of NEC. It can detect air in the portal veins (pneumoportogram) earlier than radiography. Ultrasound scanning can also detect a (small) pneumoperitoneum more easily and with greater sensitivity (indication for surgery!).

Imaging

The imaging findings of NEC lag well behind its clinical manifestations. Almost invariably, the child has already been placed on antibiotics by the time of radiologic evaluation and the appearance of initial x-ray signs.

Radiography

The plain abdominal radiograph shows separated and distended bowel loops (bowel wall edema). All morphologic imaging findings are nonspecific, however, and there are no specific radiographic criteria for NEC.

Pneumatosis. Pneumatosis of the bowel wall is strongly suggestive of NEC but is not specific and may be found in other inflammatory bowel diseases. For example, it may occur in the setting of a rotavirus infection, which is the most frequent cause of enteritis in infants.

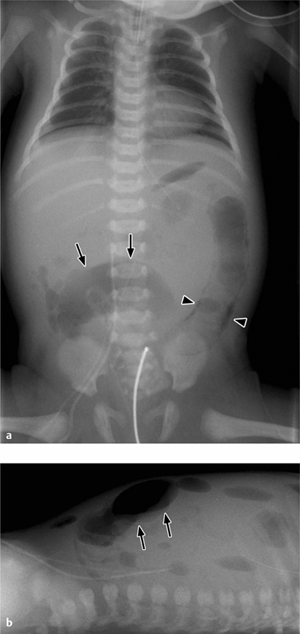

Subsequent air migration through the mesenteric veins leads to a pneumoportogram (in about 10% of cases), which does not correlate with the severity of the disease (Fig. 7.2).

Perforation. NEC is responsible for more than 50% of pediatric abdominal perforations. Pneumoperitoneum is an indication for surgical treatment (Fig. 7.3).

The supine abdominal radiograph will show the following signs of “free air” in cases where perforation has occurred (Table 7.4):

Air bordering the falciform ligament on both sides

Air bordering the falciform ligament on both sides

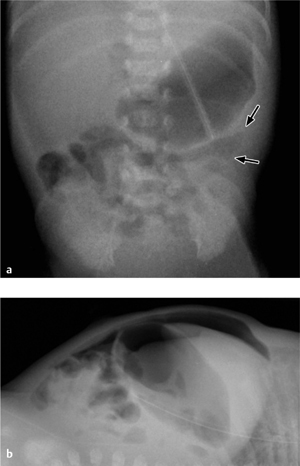

Continuity of the diaphragm shadow across the midline (unlike pneumothorax, which is confined to one side) (Fig. 7.4)

Continuity of the diaphragm shadow across the midline (unlike pneumothorax, which is confined to one side) (Fig. 7.4)

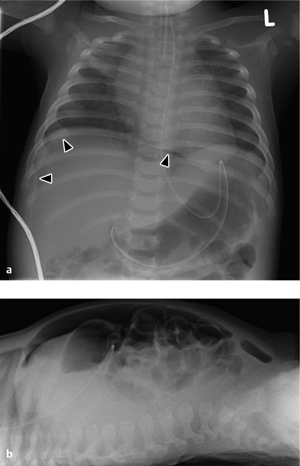

Intramural and extramural air marking both sides of the bowel wall (Rigler sign, Fig. 7.5b)

Intramural and extramural air marking both sides of the bowel wall (Rigler sign, Fig. 7.5b)

Triangular air collections between the bowel loops (triangle sign, Fig. 7.5)

Triangular air collections between the bowel loops (triangle sign, Fig. 7.5)

Rounded midabdominal lucency (football sign) on the supine radiograph caused by anterior migration of large amounts of free air (Fig. 7.6)

Rounded midabdominal lucency (football sign) on the supine radiograph caused by anterior migration of large amounts of free air (Fig. 7.6)

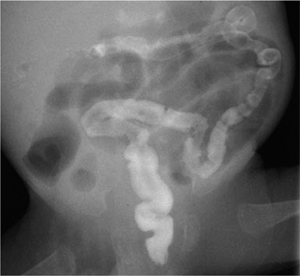

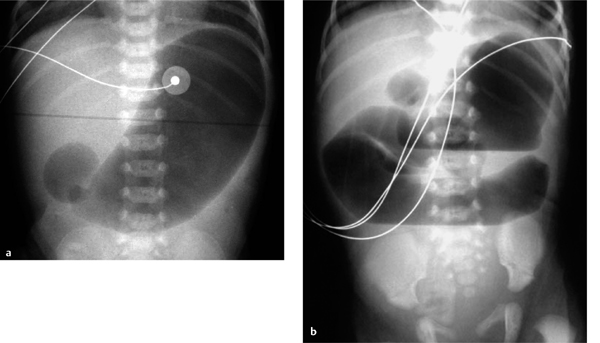

Fig. 7.2 Necrotizing enterocolitis with pneumatosis of the colon wall (arrowheads) and a rounded collection of free air (football sign) due to a perforation (arrows).

Note the displacement of the arterial umbilical catheter.

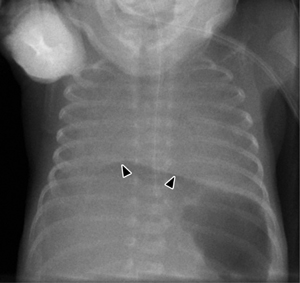

Fig. 7.3 a, b Necrotizing enterocolitis.

a Pneumatosis of the colon wall (arrowheads) and free air following a perforation (football sign, arrows).

b Cross-table view confirms the free-air collection along the anterior abdominal wall.

Fig. 7.4 Continuous diaphragm sign caused by intraperitoneal free air.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ultrasonography

Thickening of the bowel wall, intramural air, and free fluid are demonstrated equally well by ultrasound scanning. Doppler sonography of the superior mesenteric artery is an important study that will show an increased resistance index in NEC. This examination should be done in the fasted state, however, to avoid a physiologic postprandial rise in the resistance index.

Fig. 7.5 a, b Triangle sign.

Triangular free-air collection between the bowel loops (a) with intramural and extramural air bordering both sides of the bowel wall (b, cross-table view).

Fig. 7.6 a, b Football sign.

a With a very large collection of free air, it is easy to miss the diffuse increase in lucency.

b Lateral projection demonstrates free air along the anterior abdominal wall.

Malrotation and Volvulus

In normal intrauterine development, the gut undergoes three 90° counterclockwise rotations before reaching its definitive position. If these rotations are absent or incomplete, the result is nonrotation or malrotation of the intestines. Malrotation is a major developmental anomaly in children because it may lead to duodenal atresia and stenosis, volvulus, and perforation.

In newborns with a normally rotated bowel, the mesenteric root extends from the duodenojejunal loop to the distal ileum and thus provides for a long, stable fixation of the bowel. With malrotation, however, the mesenteric root is significantly shortened and offers less resistance to volvulus, which leads to vascular and intestinal stenosis. Fibrous peritoneal thickenings called Ladd bands stretch from the cecum to the liver or to the posterior abdominal wall, additionally causing duodenal stenosis (Fig. 7.7).

Clinical Aspects

More than 70% of affected children present with bilious vomiting and abdominal pain, possibly accompanied by muscular guarding. Less dramatic symptoms are anorexia, nausea, and vomiting. All children who present with bilious vomiting should undergo a small bowel contrast study to exclude volvulus.

Imaging

Radiography

Malrotation. Malrotation is difficult to recognize in the abdomen plain film of small children. The colon does not yet show the normal haustrations of adults, making it difficult to distinguish between large and small bowel. In most cases the cecum cannot be accurately localized.

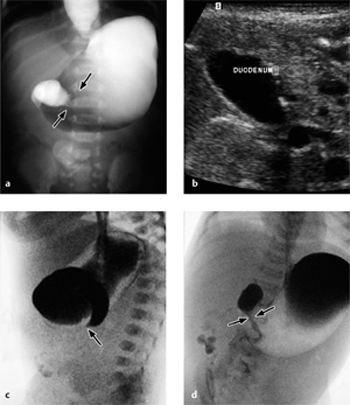

Fig. 7.7 a–d Malrotation with massive dilatation of the stomach and distal esophagus secondary to duodenal stenosis caused by a Ladd band (arrows).

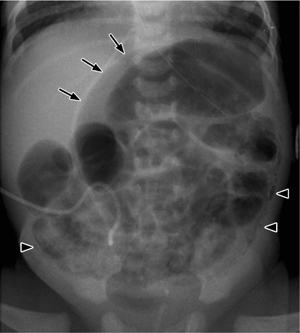

Fig. 7.8 Volvulus.

Plain radiograph shows gas-distended whorled bowel loops in the midabdomen (whirlpool sign). Decreased blood flow causes signs of wall thickening with separation of bowel loops (thumbprinting).

Diagnosis is aided by contrast examination. This may consist of a contrast enema, which will confirm that the cecum is outside the right lower quadrant of the abdomen. Another option is to administer contrast medium by gastric tube to define the location of the Treitz ligament: With a normally rotated bowel, the Treitz ligament occupies a left paravertebral location at the level of the duodenal bulb. With malrotation, the Treitz ligament has a variable location but usually occupies an inferior position on the right side.

Volvulus. The most serious complication of malrotation besides perforation is volvulus, which must be diagnosed quickly because vascular compromise may cause extensive, life-threatening intestinal necrosis.

The plain abdominal radiograph is nonspecific in the great majority of cases. Ideally the film will show a “whirlpool sign,” or a whorled arrangement of gas-distended bowel loops in the midabdomen (Fig. 7.8). A gasless abdomen on plain radiography signifies an incomplete vascular obstruction in which gas is still absorbed, while the picture of a distal obstruction (dilated air-/ fluid-filled bowel loops) associated with malrotation indicate severe intestinal ischemia.

With malrotation, the cecum is located in the right upper quadrant. This is also true in ca. 20% of normal cases, however, and so the diagnosis of malrotation requires additional signs such as abrupt “bird-beak” tapering of the contrast column in the twisted small bowel.

Ultrasonography

In most cases ultrasound scanning can verify the diagnosis by showing the inverted arrangement of the mesenteric vessels (the mesenteric vein is to the left of the mesenteric artery). Sonograms can also demonstrate the twisted mesenteric root. Additional sonographic signs are a dilated duodenum with hyperperistalsis, a thickened bowel wall in the right flank, and free fluid.

Although the detection of positive sonographic criteria is diagnostic, volvulus is not excluded by negative ultrasonographic findings.

Gastrointestinal Atresia and Stenosis

Atresias of the gastrointestinal tract are much more common in the small bowel than in the colon (1 : 750 births in the small bowel, ileum > jejunum, 1 : 3500 in the duodenum, 1 : 40 000 in the colon). The anomalies are believed to result from a disturbance of intrauterine blood flow.

Gastrointestinal stenoses may have an extraintestinal cause such as malrotation, Ladd bands, a thickened Treitz ligament, or an annular pancreas. Stenoses are less common than atresias and are generally less impressive in their symptoms and imaging findings, depending on the degree of obstruction.

Diagnostic Strategy

Contrast examination is not indicated for the evaluation of high atresias and stenoses due to the risk of aspiration. In these cases the diagnosis is established by plain abdominal radiographs and ultrasonography, unless the condition has already been identified by prenatal tests.

An incomplete stenosis may present with (misleading) air distension of the bowel distal to the stenosis, in which case (oral) contrast examination can confirm the diagnosis.

Clinical Aspects

The onset and course of clinical manifestations depend on the site of the obstruction. Duodenal atresia presents very early with bile-stained vomiting, whereas ileal atresia does not become symptomatic until several days after birth. Anal atresia is usually diagnosed in utero and rarely leads to an acute abdomen.

Fig. 7.9 a, b Congenital causes of an acute abdomen.

Duodenal stenosis (double bubble sign, a) and jejunal atresia (b) are each associated with massive distension of the proximal gastrointestinal tract and absence of air distal to the stenosis.

In colonic atresia the cecum and ascending colon are greatly distended, especially with a competent ileocecal valve. Contrast enema demonstrates a normal-sized colon with meconium in the presence of a distal stenosis, and an empty, unused microcolon in the presence of a proximal stenosis.

Complicated ileal atresia. In complicated ileal atresia or “apple-peel syndrome,” large portions of the ileum and the distal superior mesenteric artery are absent. The small bowel mesentery is hypoplastic, and the bowel remnant distal to the atresia is wrapped around the vessels of the right colon. The abdominal radiograph shows a high obstruction with dilatation of the stomach, duodenum, and jejunum. Contrast enema demonstrates a microcolon with a coiled ileal attachment that mimics volvulus. The cecum may occupy a high subhepatic location in these cases, and malrotation may also be present. The survival rate of complicated ileal atresia is less than 50%.

Contrast studies are indicated for distal stenoses and atresias to localize the obstruction and differentiate the cause (e. g., malrotation vs. atresia vs. stenosis).

Imaging

The plain abdominal radiograph in duodenal atresia shows a double-bubble sign caused by the air-filled stomach and duodenum with an absence of air distally (Fig. 7.9a).

The more aboral the site of the atresia, the less pronounced the distension. In jejunal atresia the stomach and duodenum are greatly dilated (Fig. 7.9b) while the colon is of normal size, because the ileum is producing sufficient fluid so that the colon remains “used.”

Congenital Megacolon (Hirschsprung Disease)

Congenital disturbances of the autonomic nervous system (myenteric plexus) may occur anywhere in the lower gastrointestinal tract (small and large bowel). One of the most common forms is Hirschsprung disease, which is characterized by an aganglionic segment in the rectum (> 75%). The diagnosis is confirmed by anorectal biopsy and manometry.

Clinical Aspects

The cardinal symptom of Hirschsprung disease is constipation. The disease may also present in newborns as neonatal ileus or bowel obstruction after weaning, resulting in an acute abdomen.

Imaging

The abdominal radiograph shows marked distension of the colon (Fig. 7.10). Contrast medium should be administered carefully, as an overvigorous contrast enema could mask the easily distended aganglionic segment. Contrast enema can demonstrate the aganglionic segment and especially the transition zone from the aganglionic to dilated segment.

Fig. 7.10 Congenital megacolon (Hirschsprung disease).

Note the massive dilatation of the descending colon and complete absence of air (!) in the distal rectum.

Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis

Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis (HPS) is caused by local thickening of the pylorus muscle. The etiology is unknown. It predominantly affects males (4 : 1), and is diagnosed between 4 and 6 weeks of age. HPS has a familial disposition with an incidence of 1 in 3000 live births.

Clinical Aspects

The clinical presentation of HPS ranges from nonbilious projectile vomiting to life-threatening dehydration in severe cases.

Diagnostic Strategy

Although the diagnosis of HPS once relied on abdominal radiographs and oral contrast examination, ultrasonography has now become the primary imaging study. The gallbladder is imaged in longitudinal section, and the transducer is then angled medially to define the pylorus.

The sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value of ultrasound scanning is in the high 90’s (96%, 99%, and 99%, respectively). Nondefinitive cases should be reexamined in 24–48 hours. The indication for surgical treatment is based mainly on clinical findings, with ultrasonography serving as an adjunct.

Intussusception

Intussusception occurs when one bowel segment invaginates into the lumen of the adjacent distal segment. Ileocolic intussusception, in which the terminal ileum invaginates into the cecum, is by far the most common form (85%). Colocolic and ileoileal intussusceptions are less common and may be secondary to the ileocolic form.

An obstructing lesion creating a lead point for the intussusception (duplication cyst, enlarged lymph nodes, polyps, etc.) should be excluded. An increased seasonal incidence in the spring and fall suggests an infectious etiology relating to lymph node enlargement in the cecal region. Intussusceptions are more common in children with Peutz–Jeghers syndrome and Henoch–Schönlein purpura.

Intussusception may occur in children of any age. It is most common between 3 months and 1 year and shows a 2 : 1 predilection for males. In children more than 6 years old, a tumor (lymphoma) should definitely be excluded as a possible lead point for the intussusception.

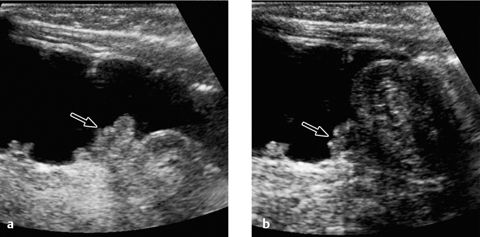

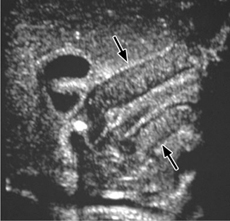

Fig. 7.11 Pyloric stenosis.

Ultrasonographic appearance of hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. The pyloric channel is longer than 16 mm with a wall thickness greater than 3 mm.

Imaging

The ultrasound scan typically shows a target sign. The pyloric channel is more than 16 mm long and its wall is thickened to more than 3 mm (Fig. 7.11). Additional findings are absence of pyloric relaxation, hyperperistalsis of the stomach, and absent or greatly delayed passage of liquid through the pylorus (drink test).

Radiographs after oral contrast administration demonstrate the filiform stenosis and the curved and elongated pylorus with markedly delayed passage of contrast medium.

Differential Diagnosis

Differentiation is required from pylorospasm, in which follow-up images will again show a normal wall thickness of the pylorus. If the stomach is empty, the collapsed antrum may mimic a thickened pylorus (drink test to distend the antrum).

Clinical Aspects

Typical symptoms are colicky abdominal pain (80%), bile-stained vomiting (75%), and bilious stool (60%). Children diagnosed very late may present with clinical signs of meningism while abdominal complaints are less prominent.

Diagnostic Strategy

The diagnosis and treatment of intussusception formerly relied on contrast enema under fluoroscopic guidance, but today both functions can be accomplished using ultrasound scanning (5–7.5 MHz). Plain abdominal radiographs are obtained to exclude free air (indication for surgery).

|

Absolute contraindications

|

|

Relative contraindications

|

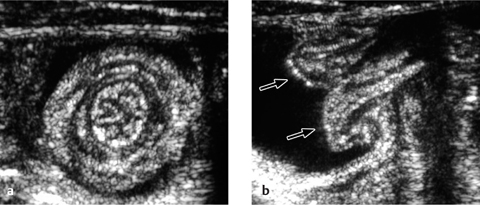

Fig. 7.12 a, b Intussusception.

Transverse and longitudinal ultrasonographic findings. Arrows indicate the intussuscepted bowel.

Fig. 7.13 a, b Intussusception.

Appearance of an ileocecal intussusception as per ultrasound scan (arrow indicates the ileocecal valve).

A nonsurgical hydrostatic reduction requires cooperation among the radiologist, pediatrician, and (pediatric) surgeon. Absolute and relative contraindications to this procedure should be noted (Table 7.5). Signs of small bowel obstruction are not a contraindication.

Imaging

Ultrasonography

The longitudinal ultrasound scan shows a “pseudo-kidney” with a hypoechoic rim (edematous bowel wall) and an echogenic center (mucosa of the intussusceptum). High-resolution probes will show multiple ringlike structures representing the different wall layers. A transverse scan displays the “crescent-in-doughnut” sign, in which the intussuscepted bowel and indrawn mesentery appear in cross-section as a swirled echogenic structure (Figs. 7.12, 7.13).

The absence of detectable Doppler flow signals indicates vascular obstruction and is an indication for immediate surgery. A small amount of free fluid has no effect on management. The detection of fluid in the intussuscepted bowel segment often correlates with an unsuccessful nonsurgical reduction attempt. Even so, a radiological reduction should always be attempted first. Ultrasonography can also identify the cause of the intussusception (Meckel diverticulum, lymph node, duplication cyst).

Radiography

Plain radiographic findings are typical in about 50% of cases, nonspecific in 25%, and normal in 25%. “Typical” radiographic signs are a soft-tissue structure with small lucencies (fat) or a peripheral ring of air accompanied by signs of intestinal obstruction.

Reduction Methods

Fluid instillation. Hydrostatic reduction is performed under ultrasound guidance. A highly diluted, warmed solution of contrast medium in water (1 : 20 to ca. 500 mL of water-soluble contrast medium) is administered through an enema tube to reduce the intussuscepted segment by mechanical pressure. The use of a water/contrast mixture makes it possible to switch later from a sonographically to a fluoroscopically guided technique.

The fluid is suspended at a height of 100–130 cm above the table top (equivalent to about 70–100 mmHg) to generate the necessary pressure. Occasionally the reservoir can be raised to 160 cm to produce a maximum pressure of about 120 mmHg (a 30-cm water column corresponds to ca. 22 mmHg). A total fluid volume of 500 mL to a maximum of 1000 mL is instilled under ultrasound guidance.

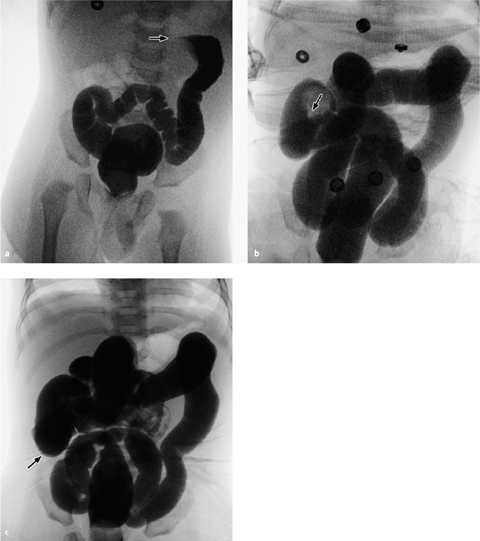

Fig. 7.14 a–c Reduction of intussusception.

Documentation of a successful reduction from the splenic flexure toward the ileocecal valve.

Reduction. A fluoroscopically guided reduction is supported by manual pressure while an sonographically guided reduction is aided by probe pressure. The criterion for a successful reduction is the passage of fluid into the terminal ileum.

The therapeutic result is documented by a sonogram or a plain radiograph. Both must demonstrate free fluid passage into the proximal bowel segment (e. g., from the cecum as far into the ileum as possible) (Fig. 7.14).

Pneumatic reduction. An alternative to hydrostatic reduction (sonographically or fluoroscopically guided) is pneumatic reduction, in which air is insufflated under fluoroscopic guidance to reduce the invaginated bowel. Both methods are well tested and effective; the preferred method is the one that is more familiar to the radiologist.

Complications

The recurrence rate after a successful nonsurgical reduction is 5–10%, with most recurrences developing within the first 72 hours. An intussusception may recur several times, but multiple nonsurgical reductions (up to five) may be performed. The perforation rate with hydrostatic reduction is less than 0.5%.

Summary

The differential diagnosis of acute abdominal pain in children is very broad and varies with the age of the patient. Extra-abdominal diseases may also underlie an acute abdomen. Ultrasonography is the primary imaging modality for evaluating an acute abdomen in children.

Meconium ileus is often the initial manifestation of cystic fibrosis. Therapeutic contrast enema is successful in up to 60% of cases.

Pneumatosis of the bowel wall is strongly suggestive of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) but is also seen in other inflammatory bowel diseases. There are no specific radiographic signs for NEC.

In every child who presents with bilious vomiting, volvulus should be excluded by contrast administration via gastric tube or confirmed by detecting a corkscrewlike configuration of the small bowel and cutoff of the contrast column. Volvulus can also be detected by ultrasound scanning but is not excluded by negative sonographic findings.

The more aboral the site of an atresia, the less the distension of more proximal gastrointestinal structures. Contrast examination is appropriate for locating a distal stenosis or atresia and determining its cause.

The main symptom of Hirschsprung disease is constipation. The disease may cause intestinal obstruction in newborns. Contrast enema should be performed carefully, as it can easily distend the aganglionic segment.

Today, hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is diagnosed sonographically. The pyloric channel is more than 16 mm long and its wall is thickened to more than 3 mm. Pylorospasm can be excluded by follow-up scans.

Intussusception can also be diagnosed by ultrasound scanning. The longitudinal scan demonstrates a “pseudo-kidney” while the transverse scan shows a “crescent-in-doughnut” sign. Treatment consists of hydrostatic or pneumatic reduction. The absence of Doppler flow signals indicates vascular obstruction, however, and is an indication for immediate surgery.

Atresia and stenosis

Atresia and stenosis Pyloric hypertrophy

Pyloric hypertrophy Appendicitis

Appendicitis Meconium ileus

Meconium ileus Intussusception

Intussusception Diseases of adnexa

Diseases of adnexa Malrotation and volvulus

Malrotation and volvulus Duplications

Duplications Urologic diseases

Urologic diseases Necrotizing enterocolitis

Necrotizing enterocolitis Foreign-body ingestion

Foreign-body ingestion Blunt abdominal trauma

Blunt abdominal trauma Hirschsprung disease

Hirschsprung disease Gastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis Cholecystitis

Cholecystitis Biliary diseases

Biliary diseases Mesenteric lymphadenitis

Mesenteric lymphadenitis Pancreatitis (in the setting of biliary tract anomalies)

Pancreatitis (in the setting of biliary tract anomalies) Gastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis Febrile urinary tract infection

Febrile urinary tract infection Gastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis Tumors

Tumors Meckel diverticulum

Meckel diverticulum

Gastrografin should not be used in children, owing to the risk of dehydration and its toxicity to gastrointestinal mucosa in newborns.

Gastrografin should not be used in children, owing to the risk of dehydration and its toxicity to gastrointestinal mucosa in newborns.

Pneumatosis of the bowel wall is suggestive of NEC, but the disease does not have specific radiographic signs.

Pneumatosis of the bowel wall is suggestive of NEC, but the disease does not have specific radiographic signs.

Lucencies over the upper abdomen

Lucencies over the upper abdomen Air outlining the falciform ligament

Air outlining the falciform ligament Subhepatic or subphrenic air

Subhepatic or subphrenic air Rounded central lucency (football sign)

Rounded central lucency (football sign) Air outlining both sides of the bowel wall (Rigler sign)

Air outlining both sides of the bowel wall (Rigler sign) Delineation of the umbilical vessels and ligament

Delineation of the umbilical vessels and ligament Air in the scrotum

Air in the scrotum Triangular air collections between bowel loops

Triangular air collections between bowel loops

Every child with bilious vomiting should undergo a small bowel contrast study to exclude volvulus.

Every child with bilious vomiting should undergo a small bowel contrast study to exclude volvulus.

Volvulus can be diagnosed by ultrasound scanning but is not excluded by negative sonographic findings.

Volvulus can be diagnosed by ultrasound scanning but is not excluded by negative sonographic findings.

Contrast examination is useful for locating a distal stenosis or atresia and determining its cause.

Contrast examination is useful for locating a distal stenosis or atresia and determining its cause. Hirschsprung disease may lead to bowel obstruction in newborns.

Hirschsprung disease may lead to bowel obstruction in newborns.

Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is diagnosed by ultrasound scanning, which shows a pyloric canal longer than 16 mm with a wall thickness greater than 3 mm.

Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is diagnosed by ultrasound scanning, which shows a pyloric canal longer than 16 mm with a wall thickness greater than 3 mm. Severe dehydration

Severe dehydration Severe muscular guarding (peritonism)

Severe muscular guarding (peritonism) Clinical signs of peritonitis

Clinical signs of peritonitis Signs of free air on the plain abdominal radiograph

Signs of free air on the plain abdominal radiograph History longer than 48 hours

History longer than 48 hours Patient younger than 3 months or older than 2 years (underlying cause), signs of small bowel obstruction on the abdominal radiograph

Patient younger than 3 months or older than 2 years (underlying cause), signs of small bowel obstruction on the abdominal radiograph Wall thickness greater than 10 mm by ultrasound scan

Wall thickness greater than 10 mm by ultrasound scan The absence of Doppler flow signals indicates vascular obstruction and is an immediate indication for surgery.

The absence of Doppler flow signals indicates vascular obstruction and is an immediate indication for surgery.