20 Acupuncture in Treatment of Aging Spine–Related Pain Conditions

KEY POINTS

Acupuncture was introduced to Europe in the eighteenth century by returning missionaries and was mentioned in a history of surgery published in 1774 in France. In North America, widespread public and professional awareness of acupuncture commenced in 1971 when James Reston reported his observations in Beijing, as a sports journalist on a ping-pong tournament trip, in The New York Times.1 There has been a substantial increase in the use of complementary and alternative medicine in the United States since then.2 Acupuncture is the most frequently used modality in complementary and alternative medicine for the treatment of symptoms of osteoarthritis,3 and especially in the treatment of back and neck pain, or other related pain conditions, including radiculopathy resulting from disc herniations or spinal stenosis. Despite the vast application of acupuncture, evidence-based clinical research in English publications, in which most authors used the approaches of “Western style of acupuncture,” has show an inconsistent conclusion on the effectiveness of acupuncture. The Western approach of acupuncture was defined as conventional diagnosis followed by individualized acupuncture treatment using a combination of prescriptive tender, local, and distal points. This is in contrast to the approach in TCM, which would formulate an individualized diagnosis based on TCM theories of meridians and energy (or qi).4

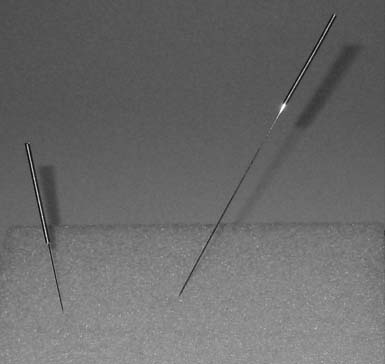

Description of the Needle

An acupuncture needle is divided into five parts (Figure 20-1): tip, body, root, handle, and tail. The tip and body of a needle are the parts being inserted into the body of a subject on the acupuncture points. The handle and tail of a needle are the parts used by a practitioner to manipulate the needle. The root connects the body and handle of a needle. Commonly used acupuncture needles are made of stainless steel, with sizes from 26 to 40 gauge and lengths from 0.5 inch to 2.5 inches. Because of the small size, quite often people describe an acupuncture needle as a “painless needle.” The tip of an acupuncture needle is blunt, even though it is very tiny. Compared with the tip of a regular needle in the same gauge number, the tip of an acupuncture needle has less chance of cutting the tissue.

Operative Techniques

Depending on the location of acupuncture points, a patient can be placed in supine, prone, recumbent, or sitting positions. Lying position is usually preferred due to the possibility of fainting in some patients from needling (Figure 20-2 ).

Needle Insertion Techniques

Finger pressing insertion. This technique is used when a short needle is used. Before inserting, the practitioner uses one fingertip (guiding finger) of the assisting hand to gently press the acupuncture point. The needle is then inserted into the skin of the acupuncture point along the edge of the guiding finger.

Tight skin insertion. This technique is used when the skin over the acupuncture point is loose. Once the acupuncture point is identified, the skin over the acupuncture point is stretched and tightened with the thumb and index fingers. The needle is inserted with the dominant hand.5

Needle Manipulation

There are various techniques in manipulating the needles manually to achieve the desired effects, which have been developed by generations of acupuncturists over thousands of years. The techniques are grouped by the needle effects, which are categorized as tonification (to treat deficiency), sedation (to treat excess), or neutral. For example, in tonification, the needle is inserted so that the angle of the needle is in the direction of energy flow on a specific meridian, and then advance the needle slowly, turning it with slow yet firm clockwise rotations as the needle is being advanced, and not penetrating too deeply. The needle can be continuously manipulated or left alone. When withdrawn, the needle should be removed quickly and the skin at the insertion point should be covered by a finger and massaged in a clockwise fashion. Sedation is the opposite of tonification. The needle is angled against the direction of energy flow on the meridian and is inserted quickly and deeply with rapid counterclockwise rotations. The needle should be withdrawn slowly and the surface should not be touched after removal of the needle. The duration of the treatment is usually 20 to 40 minutes.1

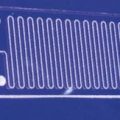

Electric stimulation became available in modern times. The electrodes are connected to the needles. The negative lead is attached to the needle(s) where the electron flow is started, whereas the positive lead is attached to the needle(s) where the flow is directed to. The low-frequency impulse, between 2 and 8 Hz, is considered to have the tonification effect. Higher frequency impulse, between 70 and 150 Hz, is used on the points surrounding the painful area, especially in musculoskeletal pain conditions.1

Other Modalities and Techniques Related to Acupuncture and the Meridian System

In addition to the commonly used body acupuncture needles and needling techniques, there are other subsystems, such as ear acupuncture (auricular acupuncture), scalp acupuncture, hand acupuncture, three-sided needle bleeding method, and seven star needle (brush of needles) tapping. Moxibustion, guasha, and cupping are also the techniques used in the comprehensive acupuncture regimen. One of the most commonly used techniques is called Tui Na. According to one of the most popular teaching textbooks used by many TCM medical schools in China, Tui Na is regarded as an equally important method as acupuncture in the treatment of musculoskeletal disorders, especially in spine-related pain conditions.8 Tui Na involves deep tissue manipulation on the acupuncture points along meridians, also manipulation of the joints, muscles, and tendons. The goal of Tui Na is to restore the flow and balance of energy along the meridians and the biomechanical alignment. The application of Tui Na is essential in the treatment of spine-related pain and other organ diseases, especially in the pediatric population.8 Presently, because of various reasons, Tui Na has been introduced to Western societies only as “acupressure” and categorized as a massage therapy with limited medical content.

Application of Meridian Theory in Spine-Related Pain Conditions

In TCM, the framework of diagnosis and point selection for treatment is based on the theoretical network of the meridian system and the internal organ subsystem related to the meridian system, where the names of the internal organs are regarded as the names for the subsystem with particular functionalities rather than the actual anatomic entities. For instance, Spleen in TCM represents a functional subunit in the body to facilitate digestion and transportation of the nutrients to the rest of the body via the meridians in general, not the actual organ called the spleen in Western medicine. The names of the internal organ subsystems that are used to name the meridians include Lung, Pericardium, Heart, Large Intestine, San Jiao (Triple Heater), Small Intestine, Bladder, Gallbladder, Stomach, Spleen, Kidney, and Liver. These twelve principal meridians are the primary subcircuits of the structure and functions throughout the body, which consists of three pairs of yin and yang meridians in a limb:

Based on the framework described previously, clinical information is analyzed by clinicians to make TCM diagnoses of specific medical conditions and to identify appropriate points to treat. For example, the symptoms and signs of lumbar intervertebral disc herniation at a given spinal segment can be considered as pathological changes on Du meridian (on the midline in the back), Gallbladder meridian of Foot Shao Yang (on the lateral aspect of the leg), Bladder meridian of Foot Tai Yang (on the posterior aspect of the back down the leg), or Kidney meridian of Foot Shao Yin (on the medial aspect of the leg). The TCM diagnosis can be classified into blood stagnation syndrome of Du meridian, damp-heat excess syndrome of Gallbladder meridian, wind-cold-damp syndrome of Bladder meridian, and Kidney-Yang deficiency syndrome.6 Then the acupuncture treatment is delivered to the points on the related meridian(s).

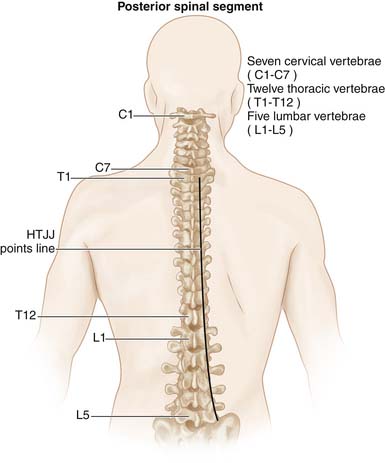

Hua Tuo Jia Ji Points

Another set of points that is also commonly used for treatment of spine-related medical conditions are the points at each vertebra along the spine, slightly lateral to the midline bilaterally, called Hua Tuo Jia Ji (华佗夹脊; HTJJ) points. Hua Tuo Jai Ji points are believed to be named after Hua Tuo, one of the most famous ancient Chinese physicians (110 ad to 207 ad) and is regarded as the father of surgery in ancient Chinese medicine. Those points are not only important in the treatment of spine-related pain condition, but also commonly used in treating other internal organ disorders. However, HTJJs were only documented in a few books historically, despite their vast clinical application. Hua Tuo Jai Ji points are described as the points located from the first thoracic vertebra to the fifth lumbar vertebra. It was recently proposed that the landmarks of HTJJ points are the facet joints along the spine, including the cervical region (Figure 20-3 ).7 The application of the HTJJ system is relatively straightforward, because of its segmental distribution along the spine. The targeting points usually correspond to the level of the vertebrae and nerve roots involved in the pathological processes. The hypothesized mechanism is that stimulation of the HTJJ points affects not only the nerve roots but also the paraspinal muscles and the chain of sympathetic ganglia along the spine.7

Research Background of Basic Sciences and Clinical Outcomes

From the late 1950s, there has been a considerable amount of government- funded research in basic sciences and clinical outcomes of TCM in China, especially of acupuncture. Since the early 1970s, more and more studies on acupuncture have been published in the English literature from many disciplines of basic and clinical sciences. Acupuncture is probably the most thoroughly researched physical modality in medicine for its analgesic effects. The analgesic events observed from electrical acupuncture stimulation were found to be related to the activities of the endogenous opioid peptide system. Animal studies also suggest that acupuncture-induced analgesia may be mediated by substances released in the cerebrospinal fluid. Both low-frequency and high-frequency electric stimulation in rats could induce analgesia, but different frequencies produce different effects in terms of the types of endorphins released. The animal studies indicate that the analgesic effect of acupuncture can be considered a general phenomenon in the mammalian world.1

The development of neuroimaging tools, such as positron emission tomography (PET) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), has taken the study of acupuncture’s effects on the activity of human brain to another level. Studies using PET have shown that thalamic asymmetry present among patients with chronic pain was reduced after acupuncture treatments. There are studies that reported the relationships between particular acupuncture points and visual cortex activation on the fMRI. These powerful new tools open the possibility to new scientific studies on this ancient therapy.9

There has been a large volume of reports and cohort studies reporting the effectiveness of acupuncture treating spine-related pain conditions, especially neck and back pain.1 It is difficult to design a double-blind study because of the lack of a true sham acupuncture technique. Only a few randomized, controlled studies have reported that acupuncture is more effective in the treatment of back pain than controls or placebo, in which medications or usual care including physical therapy are used as the control10; whereas some other studies reported no better effectiveness of acupuncture compared to controls or placebo.4 The large-scale studies are mostly conducted using the Western style of acupuncture. Some case reports and cohort studies included the diagnoses of disc herniation, spinal stenosis, and spondylolisthesis. However, most of the randomized and controlled studies in large cohorts focused on nonspecific neck and back pain, and yet the objectives of the studies were the treatment of pain rather than the possible pain generators or pathologies of the spine.4,10 A recent study demonstrated long-term pain relief by needle acupuncture compared with placebo in patients with chronic low back pain. The authors concluded that acupuncture did not seem to be a suitable treatment modality for neuropathic pain and it was sometimes indicated for the treatment of chronic nociceptive pain.11

Conclusions

Although the effectiveness of acupuncture in the treatment of spine-related pain conditions remains controversial in English publications, the clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society favors the use of acupuncture. For patients who do not improve with self-care options, clinicians should consider the addition of nonpharmacologic therapy with proven benefits: for acute low back pain, spinal manipulation; for chronic or subacute low back pain, intensive interdisciplinary rehabilitation, exercise therapy, acupuncture, massage therapy, spinal manipulation, yoga, cognitive-behavioral therapy, or progressive relaxation (weak recommendation, moderate-quality evidence).12

1. Helmes Joseph M. Acupuncture energetic—a clinical approach for physicians, second ed. Berkeley, California: Medical Acupuncture Publishers; 1997.

2. Eisenberg D.M., Davis R.B., et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997: results of a follow up national survey. JAMA. 1998;289:1569-1575.

3. Ernst E. Acupuncture as a symptomatic treatment of osteoarthritis—A systematic review. Scand. J. Rheumatol.. 1997;26:444-447.

4. White P., Lewith G., Prescott P., Conway J. Acupuncture versus placebo for the treatment of chronic mechanical neck pain. Ann. Intern. Med.. 2004;141(12):911-919.

5. Enqin Zhang. Chinese acupuncture and moxibustion. Publishing House of Shanghai College of Traditional Chinese Medicine; 1990. pp. 340–364

6. Wang L.P. Meridian differentiation of lumbar intervertebral disc herniation (Article in Chinese). Zhongguo Gu Shang. 2009 Oct;22(10):777-778.

7. Cai Chunbo. Revisit of the anatomy of Hua Tuo Jai Ji points. Med. Acupunct.. 2007;19(3):125-128.

8. Dafang Yu, Tui Na Xue (in Chinese) Publishing House of Shanghai Sciences and Technology (1984) 7-22

9. Shen J. Research on the neurophysiologic mechanisms of acupuncture: review of selected studies and methodological issues. J. Altern. Complement. Med.. 2001;7(Suppl. 1):S121-S127.

10. Cherkin D.C., Sherman K.J., Avins A.L., Erro J.H., Ichikawa L., Barlow W.E., Delaney K., Hawkes R., Hamilton L., Pressman A., Khalsa P.S., Deyo R.A. A randomized trial comparing acupuncture, simulated acupuncture, and usual care for chronic low back pain. Arch. Intern. Med.. 2009 May 11;169(9):858-866.

11. Carlsson C., et al. Acupuncture for chronic low back pain: a randomized placebo-controlled study with long-term follow-up. Clin. J. Pain. 2001;17(4):296-305.

12. Chou R., Qaseem A., Snow V., Casey D., Cross J.T.Jr., Shekelle P., Owens D.K. Clinical Efficacy Assessment Subcommittee of the American College of Physicians; American College of Physicians; American Pain Society Low Back Pain Guidelines Panel, Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann. Intern. Med.. 2008 Feb 5;148(3):247-248.