Acquired Lesions of the Small Intestines

Small Bowel Obstruction

Abnormalities that mimic obstruction include chronic intestinal pseudoobstruction (CIPO), defined by a consensus group as a “rare, severe disabling disorder characterized by repetitive episodes or continuous symptoms and signs of bowel obstruction, including radiographic documentation of dilated bowel with air-fluid levels, in the absence of a fixed, lumen-occluding lesion.”1,2 Dilation of various parts of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, including the small bowel, is characteristic of intestinal pseudoobstruction; these entities are further discussed in Chapter 106.

Etiology

Adhesions

Adhesions are a common cause of obstruction in patients who have undergone prior abdominal surgery. Obstruction secondary to adhesions is more common in neonates, particularly after surgery for repair of abdominal wall defects such as gastroschisis. In older children, adhesive obstruction occurs most often after pelvic surgery, usually after appendectomy.3 The postappendectomy incidence does not seem to be related to positive versus negative appendectomy, but some data suggest that it is decreased after a laparoscopic versus an open procedure.4

Incarcerated Hernia

Several types of hernias can lead to bowel obstruction in children, and overall they are responsible for approximately 10% of bowel obstructions.3

Inguinal hernias are a relatively common condition in children, with an overall incidence between 0.8% and 4.4%.5 The vast majority of inguinal hernias in children are indirect hernias related to a patent processus vaginalis.6 The incidence of inguinal hernia is 10 times higher in boys than in girls.7 Inguinal hernias have both a higher incidence (~ 30%) and a higher risk of incarceration (31%) in premature infants.8

Other hernias that can lead to SBO include mesocolic (right or left paraduodenal) hernias (see Chapter 103) and herniation of bowel around an incompletely fixated falciform ligament.

Omphalomesenteric Duct Remnants

Omphalomesenteric remnants are the residua of the embryologic yolk stalk, and they become apparent in several ways, depending on the type of abnormality and ensuing complications (see also Chapter 103). Normally, the entire attachment regresses. The lumen may be obliterated, but a fibrous cord may persist, with or without cystic remnants within it. Attachment of the mid small intestine to the anterior abdominal wall via a persistent cord may lead to distal SBO in a manner similar to an adhesion; or the remnant may predispose to volvulus of a bowel loop about the fibrous cord.

Adynamic Ileus

Adynamic ileus can cause bowel distension and may mimic mechanical obstruction. Adynamic ileus occurs invariably following major abdominal operations, and if prolonged, it may be difficult to differentiate from an early postoperative or recurrent obstruction.3 In addition, adynamic ileus may also occur in the setting of burns, trauma, and certain medications. The pathophysiology of postoperative ileus remains incompletely understood, but the disruption of the normal autonomic gastrointestinal (GI) motility is multifactorial and related to pharmacologic, inflammatory, hormonal, metabolic, and neuropsychologic influences.9

Clinical Presentation

The degree of abdominal distension depends on the level of obstruction; more distal levels are associated with greater distension. SBO in children usually presents with persistent bilious vomiting and abdominal pain.10 Infants and young children may also come to medical attention with irritability and refusal to eat. The presence of fever is concerning for ischemia and bowel compromise, particularly if accompanied by unremitting pain unresponsive to proximal decompression.

Imaging

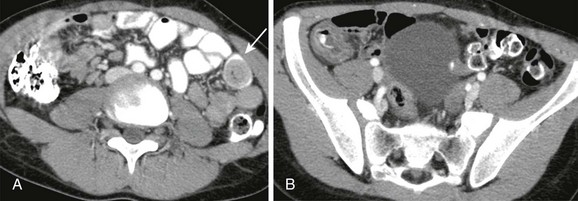

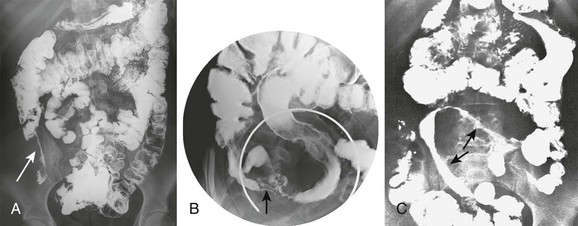

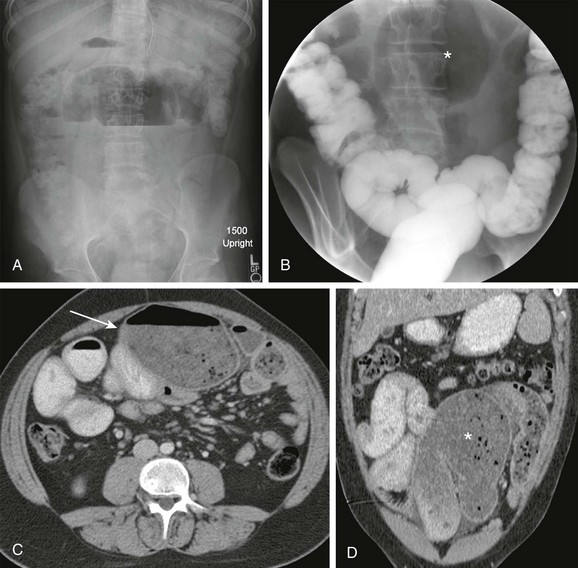

Patients with long-standing complete obstruction will demonstrate dilated loops of bowel with differential air-fluid levels on horizontal-beam images and absence of stool and gas in the colon (Fig. 105-1, A and B). In partial obstruction, gas and stool may be present in the colon; however, a caliber difference between proximal loops of dilated bowel and bowel distal to the obstruction should remain evident.

Figure 105-1 Small-bowel obstruction caused by adhesions.

A, Supine radiograph of the abdomen in an 8-year-old boy with a history of multiple abdominal operations and increasing abdominal distension shows dilated, gas-filled loops of bowel. B, Horizontal-beam left lateral decubitus image demonstrates multiple differential air-fluid levels. C, Axial computed tomography image shows a transition zone (arrow) between dilated proximal bowel loops and collapsed distal bowel loops. Adhesions resulting in a small-bowel obstruction were lysed at surgery.

CT can be helpful in revealing the level and occasionally the cause of the obstruction. Administration of oral contrast is not always necessary (see Fig. 105-1, C), and only water-soluble agents should be administered if bowel perforation is a potential complication. CT may be particularly helpful in the diagnosis of a closed-loop obstruction and obstruction related to adhesions, with dilated bowel loops seen proximally and collapsed bowel distal to the point of obstruction. The level of obstruction may also be demonstrated by SBFT.

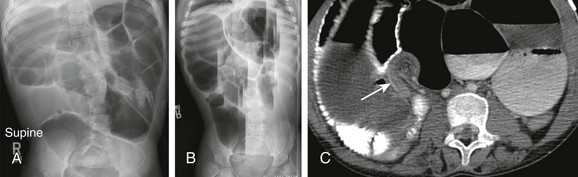

The diagnosis of an incarcerated hernia is typically established by history and physical exam, although radiographs (Fig. 105-2) or ultrasound may occasionally be used to confirm the diagnosis.

Figure 105-2 Small-bowel obstruction caused by inguinal hernia.

Supine radiograph of the abdomen in a 1-month-old boy, former 26-week gestational age, who presented with a distended abdomen and a right inguinal hernia demonstrates dilated, gas-filled loops of bowel. Bowel gas is seen within the right inguinal hernia (arrow). Obstructive symptoms improved after manual reduction of the hernia.

Treatment

The treatment for obstruction depends on its cause, but treatment is often surgical. Patients with partial obstruction who lack fever, leukocytosis, or unremitting pain can be observed with bowel decompression; in postadhesive obstruction, this treatment is successful in the majority of cases. However, patients with evidence of complete obstruction, fever, leukocytosis, and unremitting pain require prompt surgical intervention.11

In the absence of peritoneal signs, the treatment of choice for an incarcerated inguinal hernia is manual reduction, which has a success rate of 80%, followed by repair 24 to 48 hours after reduction.7 Surgical repair is also typically suggested for umbilical hernias that persist in children older than 4 years of age because of the increasing risk of incarceration with age.12

Treatment of postoperative ileus has traditionally consisted of bowel rest and decompression via nasogastric tube. More recently, investigators have advocated early enteral nutrition; nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs to decrease inflammation; minimally invasive surgical techniques, such as laparoscopy when feasible; and minimization of narcotic use for control of postoperative pain.9

The treatment of CIPO depends on the underlying cause and may include prokinetics; surgery in the form of gastrostomy, jejunostomy, and/or loop enterostomy; and total parenteral nutrition (TPN).2 Intestinal transplantation may be considered in patients with life-threatening complications from TPN.

Inflammatory Conditions of the Small Bowel

Overview

Infectious diarrhea is a major source of childhood mortality and accounts for approximately 2.5 million deaths per year worldwide.13 Viruses, bacteria, and parasites are potential causative agents of acute gastroenteritis in children, and viruses are the most common cause of pediatric intestinal infection in the United States.14

Etiology

Viral Infection: Gastroenteritis secondary to viral agents is one of the most common causes of acute infectious diarrhea, defined as acute onset of at least three loose stools per day.15 In the United States, viral gastroenteritis is most common secondary to rotavirus, adenovirus, and norovirus (Caliciviridae).15,16

Bacterial Infection: Bacterial pathogens are estimated to cause between 2% and 10% of infectious diarrhea cases in developed countries.16–18 Shigella, Salmonella, Escherichia coli, and Campylobacter are the most commonly identified bacterial agents in the United States.16 Infections with Yersinia enterocolitica, Vibrio species, Aeromonas, and Plesiomonas are more commonly found in patients in developing countries.16 Clostridium difficile can be isolated from the intestine of up to 50% of normal neonates, and this rate decreases to less than 5% by 2 years of age.16 Illness-associated C. difficile infection is often associated with decreases in other intestinal flora secondary to exposure to broad-spectrum antibiotics, such as penicillin, clindamycin, and cephalosporins; this results in antimicrobial-associated diarrhea or pseudomembranous colitis.16

Parasitic Infection: The most common intestinal parasites in the United States are Giardia lamblia and Cryptosporidium.16 Although humans are the major reservoir of infection, Giardia can infect domesticated animals, such as dogs and cats, and fecal-oral transmission occurs through contaminated water or food. Cryptosporidium may be spread by person-to-person transmission or through contaminated water, such as in swimming pools. People may also be infected through livestock, birds, and reptiles.

Helminths, or parasitic worms, include the nematodes or roundworms—ascarids, hookworms, and pinworms—and also the Platyhelminthes, or flatworms, such as schistosomes and tapeworms. One or more of these parasitic agents are estimated to infect approximately one third of the impoverished populations of developing countries.19 Among these, children and adolescents tend to harbor the largest helminthic loads, which leads to both physical and cognitive impairment in this vulnerable population.19

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV): Approximately 2.5 million children are infected with HIV worldwide, often in conjunction with other endemic conditions, such as malaria and helminthic infection.19,20 Although antiretroviral therapy has decreased the prevalence of vertical mother-to-child transmission and perinatal HIV in developing countries, approximately 420,000 children are still infected annually, primarily through mother-to-child transmission.20

Clinical Presentation

Viral Infection: Viral gastroenteritis commonly manifests with vomiting followed by severe watery diarrhea, nausea, abdominal pain, headaches, and low-grade fever.21 Associated upper respiratory symptoms are common and may precede the GI presentation.

Bacterial Infection: Considerable overlap occurs in clinical symptoms of viral and bacterial enteritis. However, high fever, shaking chills, and bloody stools are more commonly seen with bacterial enteritis than with viral gastroenteritis.16 Diagnosis may be established by the presence of stool leukocytes and positive stool culture.

Parasitic Infection: Clinical symptoms after Giardia infection are variable, and some patients may be asymptomatic. Children may have foul-smelling diarrhea with flatulence, abdominal distension, and anorexia.16 Diagnosis may be established by microscopic smear examination or immunofluorescence antibody testing of stools.

Cryptosporidium infection is usually self-limited in the immunocompetent child and may be asymptomatic or may be confused with viral gastroenteritis. Common symptoms include diarrhea, fever, and emesis.22 In immunocompromised patients, including those with HIV, the infection may have a protracted course with severe, chronic diarrhea and subsequent malnutrition and dehydration, which may result in death.16,22

Human Immunodeficiency Virus: Persistent diarrhea from a variety of pathogens may be a presenting symptom of HIV. Enteritis may be caused by the viruses, bacteria, and parasites described above. In addition, the child with HIV may be susceptible to opportunistic infections such as cytomegalovirus, Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare, and fungi, especially Candida albicans.20 HIV enteropathy can also occur as a direct effect on the bowel and is manifested as a diarrheal disease, with an incidence estimated to be between 30% and 40%. This is considered a diagnosis of exclusion, after other infectious and noninfectious causes are excluded.23

Imaging

Imaging studies are not generally indicated for diagnosis of infectious diarrhea in children. However, symptoms may sometimes mimic abdominal conditions, such as appendicitis or intussusception, and abdominal radiographs are occasionally requested to exclude other potential causes of the patient’s symptoms. Depending on the time course and the degree of motility disturbance, nonobstructive dilation of bowel loops may occur. The most common radiographic findings are fluid-filled loops of distended bowel with multiple scattered air-fluid levels on horizontal-beam radiography, in contrast to differential air-fluid levels characteristic of obstruction. Absence of stool throughout the colon is commonly seen, along with air-fluid levels in the rectum. Pneumatosis intestinalis may rarely be seen.24

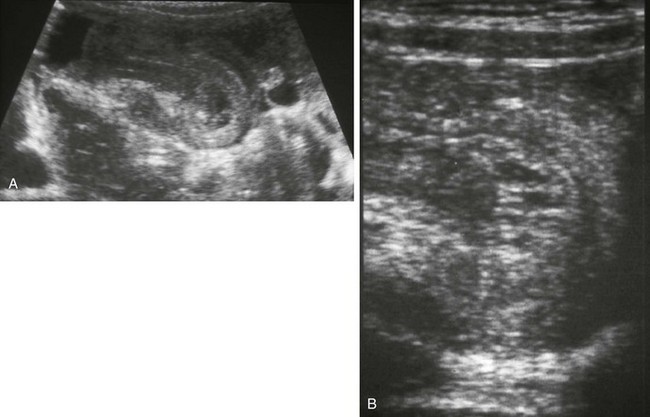

Cross-sectional imaging is not indicated in patients with clinically obvious gastroenteritis, but it is sometimes requested when other entities are being considered. US or CT may demonstrate small-bowel wall thickening, fluid-filled distended bowel loops (e-Fig. 105-3),25,26 and intraabdominal and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy.27 Real time US may reveal transient small-bowel intussusception during periods of hyperperistalsis.

e-Figure 105-3 Gastroenteritis.

A 21-month-old boy was seen with vomiting and irritability. A, Ultrasonography requested for clinical concern of intussusception reveals distended, fluid-filled loops of bowel that are otherwise normal. B, Additional image in the right lower quadrant reveals multiple enlarged mesenteric nodes, which were hyperemic on color Doppler interrogation (not shown). (Courtesy Marta Hernanz-Schulman MD, Nashville, TN.)

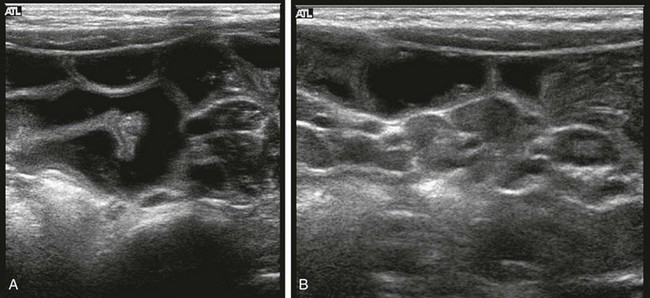

The terminal ileum and the cecum are often involved in bacterial enteritis, such as with Yersinia; this may be termed infectious ileocecitis. On imaging, inflammatory changes such as bowel wall thickening are typically apparent (Fig. 105-4). Involvement of the more distal colon may be variable. Right lower quadrant lymphadenopathy may also be seen.21,28

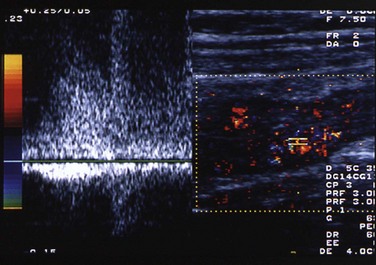

Figure 105-4 Bacterial enterocolitis.

A, Shigella enteritis. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) reveals concentric thickening and enhancement of the terminal ileum and cecum, along with a small amount of pericecal fluid (arrow). Shigella sonnei was cultured from the stool. B, For a 5-month-old with mucous diarrhea and abdominal pain, ultrasound was requested to assess for suspected intussusception. A transverse sonogram of the right lower quadrant shows a markedly thickened terminal ileum, along with a visible transition to normal bowel (arrow) more proximally. A large lymph node is seen deep to the terminal ileum. C, Transverse image in same infant as shown in B, obtained slightly more cephalad, reveals a large nodal aggregate medial to the ascending colon and anterior to the lower pole of the right kidney (calipers outline one of the nodes). D, Color Doppler image in the same infant shows marked hyperemia in the thick-walled terminal ileum and in the surrounding mesentery and lymph nodes. E, Yersinia enteritis. CT in a 9-month-old boy who had a 10 day history of fever, emesis, and voluminous diarrhea demonstrates pronounced thickening and luminal narrowing of the terminal ileum (arrows). F, Coronal reformat of the CT scan in same patient as shown in E demonstrates similar findings. Stool cultures were positive for Yersinia enterocolitica.

If contrast studies are performed in children with parasitic enterocolitis, they may show dilution of barium from fluid retention, minimal thickening of mucosal folds, and rapid or delayed transit time, depending on the chronicity of the disease. Disordered peristalsis is commonly seen. Certain specific findings can be seen, depending upon the underlying causative organism. On barium studies, Giardia produces thickened mucosal folds in the duodenum and jejunum that are associated with rapid transit time and dilution of contrast material (e-Fig. 105-5).29

e-Figure 105-5 Giardiasis.

Small intestinal barium examination in a 10-year-old girl with a history of nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and weight loss. The mucosal folds of the duodenum and the proximal jejunum are markedly thickened. Giardia was identified in the stool.

Nonspecific edema of the affected intestine is the most frequently found abnormality on barium studies in patients with HIV enteropathy. Effacement of the mucosal pattern is common,27 especially with Cryptosporidium infection.

Treatment

Treatment is dependent upon the underlying causative agent. Viral gastroenteritis is typically a self-limited condition. Oral and intravenous (IV) rehydration therapies are effective supportive interventions in cases of infectious diarrhea, particularly with viral infections. The treatment of bacterial enterocolitis also includes supportive therapy. Antimicrobial therapy is not always necessary for certain pathogens, such as Salmonella, although even in those cases, it may be needed, depending on the underlying immunocompetence of the host. Agents such as metronidazole and nitazoxanide are active against Giardia and Cryptosporidium, respectively. The pharmacopeia available for treatment of helminthic infections is relatively limited, particularly when considering the global ubiquity of these infections, and it includes diethylcarbamazine and newer agents such as albendazole and praziquantel.16,19,22

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

IBD comprises two major disorders: Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis. Crohn disease can involve any part of the GI tract, whereas ulcerative colitis only affects the colon and is discussed in Chapter 107.

Crohn Disease

The peak incidence of Crohn disease is in young adulthood, but 25% of patients come to medical attention during childhood or adolescence.30 Crohn disease is characterized by segmental transmural granulomatous inflammation of the intestine. The mucosal layer is extensively destroyed, and ulcers are usually present. The intestinal lumen is often narrowed by spasm and by edematous and fibrotic thickening of the wall. The small bowel is involved in approximately 80% of cases, and isolated small-bowel disease, without colonic involvement, occurs in approximately 30% to 40% of patients.31 The terminal ileum is most frequently involved, but the disease has been described anywhere along the GI tract, from the mouth to the anus, and may occur without terminal ileal involvement.32,33 In children, the terminal ileum is involved in 50% to 70% of cases, and 10% to 15% have diffuse small-bowel disease.34

Etiology

The exact cause of Crohn disease remains unknown, but recent work suggests that failure of intestinal immune homeostasis, with inflammatory mediators directed against gut flora, may be implicated, along with an underlying genetic susceptibility.35 The NOD2 (formerly CARD 15) gene, located on chromosome 16, regulates the immune response to bacterial products and is abnormal in 20% to 30% of pediatric patients with Crohn disease.34 T-cell activation and increased activity of proinflammatory cytokines—such as interleukins (IL) 1, 6, and 12—with decreased antiinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-4 and IL-10, are found in the mucosa of patients with Crohn disease.34,36 Approximately 30% of affected individuals have a positive family history, and there is a 50% concordance between monozygotic twins.35

Clinical Presentation

Clinical presentation and severity of disease manifestations are highly variable. Most children with Crohn disease come to medical attention with insidious onset of GI symptoms, including diarrhea, abdominal pain, anorexia, and weight loss with growth retardation at times preceding other abdominal symptoms by months or years.34 Other clinical findings include abdominal mass, pain, and perianal fistula. Some patients have symptoms that manifest acutely with right lower quadrant pain and fever, mimicking appendicitis. Crohn disease in pediatric patients may be more severe at presentation and may demonstrate a more complicated course than in adult patients.35 Extraintestinal manifestations may accompany or precede GI symptoms and include fever, aphthous stomatitis, arthralgias, arthritis, sacroiliitis, erythema nodosum, and digital clubbing. Arthritis is the most common extraintestinal condition in the pediatric population.34

The diagnosis of Crohn disease may be suggested by history and clinical exam and is further supported by radiologic exams and endoscopic and histopathologic correlative data. Endoscopic examination with biopsy is an essential step in confirming the diagnosis, excluding other entities, and differentiating between Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis in the 20% of patients with exclusively colonic involvement.31 Capsule endoscopy is a more recent but well-established technique to assess the small bowel in Crohn disease, particularly in patients whose disease is inaccessible to routine endoscopic procedures.

Imaging

Abdominal radiographs in patients with IBD may be normal. However, the most common finding is absence of stool in the involved portions of the colon.37 During an acute disease exacerbation, abdominal radiographs are more likely to show abnormalities such as ileus, bowel wall thickening, or obstruction.

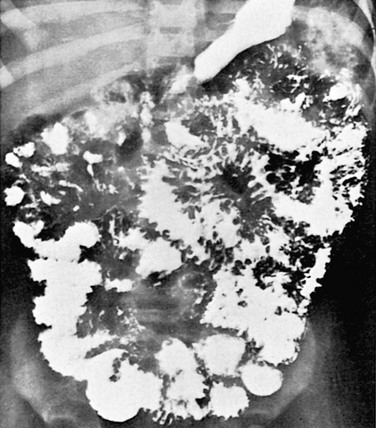

Upper GI examinations with SBFT have been frequently used to evaluate jejunoileal manifestations of Crohn disease. One of the earliest changes seen on contrast radiographic examinations is the formation of aphthous ulcers, which are present in both small bowel and colon; these represent shallow erosions surrounded by a radiolucent halos that represent edema. Other findings include nodular irregularity with linear and transverse ulceration. Extensive ulceration can lead to a spiculated or “rose thorn” appearance, which results from deep ulcers that extend into the thickened bowel wall (Fig. 105-6). The intersection of multiple linear and transverse ulcers leads to a cobblestone appearance, also known as pseudopolyps, areas of spared mucosa surrounded by adjacent denuded areas. Spasm of involved segments is frequently seen, and intermittent fluoroscopic observation is required to differentiate spasm from stricture. Narrowing of the intestinal lumen secondary to edema and fibrosis is known as the “string sign.” The mesentery becomes inflamed, thickened, and fibrotic, which causes separation and retraction of bowel loops.31,38 The sensitivity and specificity of SBFT has been estimated at approximately 90% and 96%, respectively.39

Figure 105-6 Crohn disease.

A, Frontal abdominal radiograph from small bowel follow-through in a 17-year-old girl with a history of worsening abdominal pain, fever, fatigue, and decreased appetite shows pronounced luminal narrowing of the terminal ileum (arrow) with a “string sign,” which indicates a markedly narrowed segment. Displacement of adjacent bowel loops is evident. B, Spot film of terminal ileum in an adolescent with Crohn disease. Examination reveals extensive involvement and ulceration of the terminal ileum with a “rose thorn” appearance and spasm. Involvement of the cecum is also apparent, and the appendix is incidentally noted at the cecal tip (arrow). C, Small bowel series in a 14-year-old girl reveals a markedly narrowed and rigid loop of mid small bowel (arrows). The upper arrow points to a “string sign.”

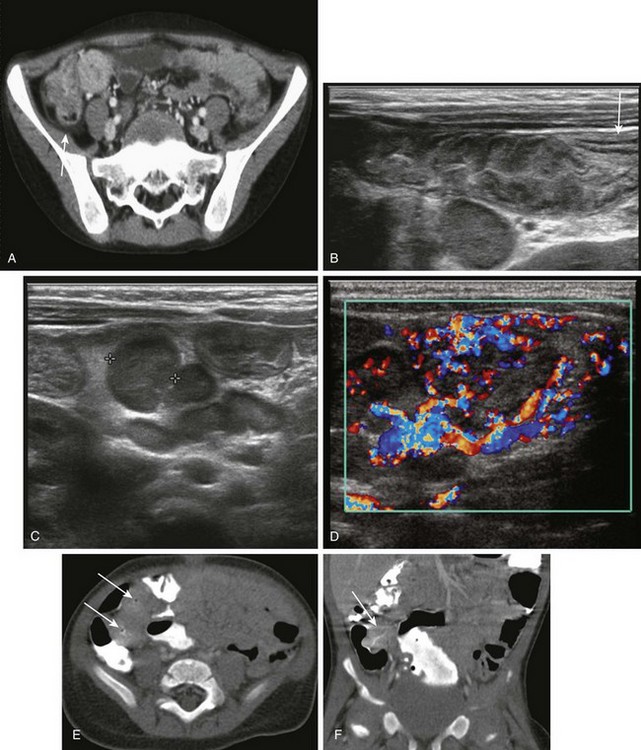

US is an excellent modality in the evaluation of patients with Crohn disease. The involved bowel segment shows a thickened wall with visible transition to uninvolved bowel. Often bowel loops are separated by intervening mesenteric fat, and small lymph nodes are seen. Bowel wall hyperemia has been noted to correlate with disease activity (Fig. 105-7).40–41 Small abscesses may be missed on US, and it is possible that remote areas of disease may be missed because of overlying bowel gas.

Figure 105-7 Crohn disease.

Transverse image through the right lower quadrant of an adolescent boy with Crohn disease. Color and spectral Doppler image shows the terminal ileum, which is markedly thickened. Flow to the wall of the terminal ileum is increased, along with venous and high diastolic arterial flow. (Courtesy Marta Hernanz-Schulman MD, Nashville, TN.)

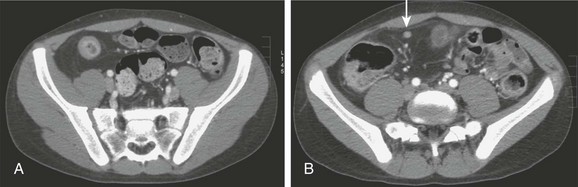

CT is now widely used and has largely replaced SBFT in many centers. CT readily identifies bowel wall thickening, mesenteric changes such as lymphadenopathy, fibrofatty proliferation (Fig. 105-8), luminal narrowing and stricture, and phlegmon formation. CT enterography entails introduction of negative bowel contrast to distend the bowel without obscuring mural enhancement. These techniques may improve identification of complications of disease, such as sinus tracts, fistulae, and strictures. Volumen (E-Z-EM, Inc., New York) is a commonly used commercial product, but whole milk (4% fat) has been reported as a useful substitute.42 The radiation dose delivered in CT versus SBFT varies, depending on the CT technique and the amount of fluoroscopy and number of radiographs obtained in the SBFT. In either case, the chronic nature of this disease and the need for repeat imaging clearly point to a nonradiation modality as preferrable for monitoring disease activity.43

Figure 105-8 Crohn disease.

A, Contrast-enhanced computed tomography through the pelvis of an adolescent boy with Crohn disease illustrates the thickened wall of the terminal ileum, hyperemic mucosa, and characteristic circumferential fat deposition, leading to increased separation of bowel loops. B, A section slightly more cephalad in the same patient shows a milder inflammatory change in a more proximal portion of the ileum and again shows fat accumulation, along with a tiny lymph node that is located just deep to the right rectus muscle (arrow).

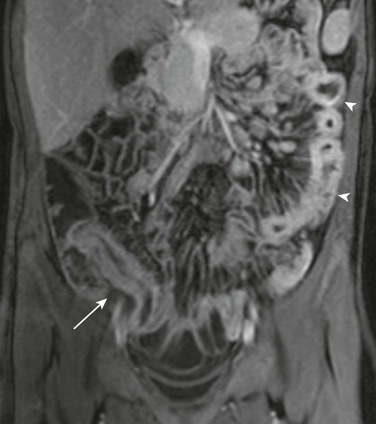

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has become more common for the evaluation of IBD with improved visualization of transmural and extraluminal disease. As with CT, MR enterography demonstrates mural hyperenhancement, bowel wall thickening, stratification and homogenous or striated wall enhancement, and stricture formation—provided adequate bowel distension is achieved (Fig. 105-9). Bowel is considered thickened when it measures greater than 3 mm.44 Stricture may be suspected if the proximal bowel is greater than 3 cm in diameter, or if there is greater than 10% luminal narrowing in the absence of proximal dilatation.45 As with CT, luminal contrast agents should be of low signal intensity to allow detection of mural enhancement, which is the most sensitive imaging finding of active disease.46 Enlarged mesenteric vessels, the so-called “comb” sign, are often seen about affected, hyperenhancing bowel loops on both MR and CT. These findings have been found to correlate with other markers of disease activity, such as elevated levels of C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate.46 Additional extraluminal findings include lymphadenopathy, fibrofatty proliferation, phlegmon, and abscess. MR enterography has better contrast resolution compared with CT, as well as the added benefit of avoiding radiation exposure, but it cannot be used in patients with MRI-sensitive devices.47 MR enterography is increasingly advocated for both the initial and follow-up evaluations for patients with Crohn disease.48

Figure 105-9 Crohn disease.

Coronal contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image from a magnetic resonance enterography study in an 11-year-old girl with Crohn disease shows a thickened and enhancing terminal ileum (arrow). Abnormal enhancement and thickening of jejunal loops in the left abdomen is also apparent (arrowheads) with prominence of the vasa recta in the adjacent mesentery (comb sign).

Prospective studies to compare MR enterography to CT enterography using state of the art techniques have revealed similar sensitivity for detection of active inflammation in the terminal ileum.32,49 MRI is considered superior to CT for assessment of perineal disease and its complications, particularly fistulae and sinus tracts.44 Dedicated contrast-enhanced pelvic MRI can detect perianal fistulae with an accuracy of approximately 90% and can be used to further classify these into various subtypes based on their relationship with the internal and external anal sphincter.46

Behçet Syndrome

Behçet syndrome is an uncommon, immune-mediated vasculitis. This chronic, relapsing condition involves multiple organ systems, including the GI tract and neurologic and cardiovascular systems. The disease is more prevalent in Mediterranean countries, the Middle East, Japan, and Southeast Asia. Prevalence in Asia is reported at approximately 30 per 100,000 population, whereas in North America, it is reported as approximately 7 per 100,000.50 Patients with this syndrome are at risk for venous and, less commonly, arterial thrombosis; complicating arterial aneurysms, including those of the pulmonary arterial system, may also occur. GI involvement with inflammation and ulceration is reported in 5% to 60% of patients, with the ileocecal area most commonly affected.51

Clinical Presentation

Disease onset is typically in the third decade; childhood onset is rare.52 Males are at two to five times greater risk compared with females.51 No specific diagnostic test is available for the syndrome; diagnosis is made by detection of recurrent mouth ulcers in association with at least two other major criteria that comprise ocular involvement, skin lesions, recurrent genital ulcerations, and the presence of pathergy.

Imaging

Involvement of the bowel with Behçet disease is characterized by ulcerations—which on GI contrast studies appear as deep, “collar-button” ulcers—and thickening of adjacent mucosal folds.50 The deep ulcerations can result in perforation and formation of fistulae, which are more easily detected with cross-sectional imaging, including CT and MRI. The esophagus, terminal ileum, and right colon are most commonly affected. GI ulcerations may be confused with other inflammatory bowel diseases that share extraintestinal features.

Treatment

Corticosteroids and other immunosuppressants are indicated during disease exacerbations. Surgical resection of severely involved segments can result in recurrence, with a rate that ranges between 40% and 80%; these typically are seen within 2 years of surgery, often located near the initial anastomosis.50

Functional and Infiltrative Diseases

Cystic Fibrosis

CF is an autosomal-recessive condition caused by a faulty CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein, that results from a variety of mutations mapped to locus q31.2 of chromosome 7. This protein is involved in the regulation of Cl− transport across cell membranes, not only in the lungs, but also in the digestive system, reproductive tract, and skin. Approximately 3.3% of whites in North America are carriers of a CFTR mutation, with a homozygous prevalence of approximately 1 in 3500 whites.53

Clinical Presentation

GI involvement in patients with CF includes meconium ileus in the newborn period (see Chapter 103). Older children may show duodenal abnormalities such as dilatation, thickened folds, and ulcerations (see Chapter 104). In older children, the most common intestinal abnormality is the distal intestinal obstruction syndrome (DIOS), formerly known as meconium ileus equivalent. This syndrome occurs in approximately 15% of patients54 and is more common among older children and adolescents. Patients come to medical attention with colicky abdominal pain and a palpable right lower quadrant mass that represents impacted fecal material in the ileocolic region. Because mild to severe constipation is a common concomitant condition, the DIOS diagnosis is reserved for those patients who have signs and symptoms of SBO.

Imaging

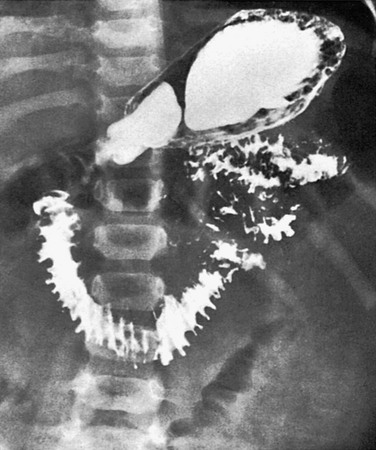

Radiographs show small-bowel dilatation with air-fluid levels; bubbly fecal material may also be present, particularly in the right lower quadrant.55 If CT is performed, dilated small-bowel loops can be followed to the site of impaction in the distal ileum (Fig. 105-10).

Figure 105-10 Distal intestinal obstructive syndrome.

A, A 7-month-old boy with cystic fibrosis and increasing abdominal distension, pain, and emesis. Upright abdominal radiograph shows a dilated, gas-filled bowel loop in the central abdomen with an increased air-fluid level. B, Contrast enema image shows no substantial reflux into the terminal ileum and persistence of the abnormally dilated bowel loop in the midabdomen (asterisk). C, Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography shows flocculent material in a dilated midabdominal bowel loop (arrow). D, Coronal reformat confirms the axial findings. Flocculent material dilating the small bowel is again seen (asterisk). Distal ileal obstruction was confirmed at laparotomy.

Patients with CF may have malabsorption with dilatated intestinal loops with thickened folds. The appendix in patients with CF is typically distended by mucoid contents, and although its contents may be expressible with compression, appendiceal diameter alone is not a reliable criterion for diagnosis of appendicitis in these patients; periappendiceal findings therefore become particularly important.56,57

Intussusception is found in approximately 20% of CF patients who come in with obstruction, with an inspissated fecal mass acting as a lead point.58 Mean age at presentation is 10 years. Clinical symptoms tend to be milder than those in idiopathic intussusception in the younger child, but radiographic findings are similar.55

Treatment

Although most patients with DIOS respond to enemas that include mucolytic agents, water-soluble contrast enemas given under fluoroscopic control also may be effective. For best results, reflux into the terminal ileum is necessary. Repeated attempts over a 24 to 48 hour period may be required to completely relieve the impaction. Surgical management may be needed in patients who do not respond to nonsurgical techniques. Treatment of intussusception is with fluoroscopic enema reduction.55

Protein-Losing Enteropathies

Etiology

Celiac Disease: Celiac disease is the most common cause of intestinal malabsorption in childhood. The disease is also known as nontropical sprue or gluten enteropathy, because the cause is gluten intolerance. Gluten is a protein that is present in wheat and related species, including barley and rye. The disease is more prevalent in Western Europe and North America, where it may affect as many as 1 of every 80 to 300 persons.59 The hypersensitivity to gluten is related to the tissue transglutaminase (TTG) enzyme, which acts as the autoantigen in celiac disease. Diagnostic tests include measurement of IgA antibody to human recombinant TTG, as well as quantitative serum IgA evaluation. Diagnosis is made when small-bowel biopsy documents villous atrophy. The disorder is associated with type 1 diabetes mellitus; Down, Turner, and Williams syndromes; and IgA deficiency.59

Whipple Disease: Whipple disease is caused by Tropheryma whipplei, and it is identified at postmortem examination in approximately 0.1% of individuals. It is much more common in men and typically presents in middle age; rarely, the disease is reported in children, most often those from developing areas with poor sanitation. Whipple disease is characterized by the presence of macrophages that persist even after eradication of the initiating organism. Although phagocytosis is normal, macrophages from affected patients appear to be unable to effectively handle the bacterial antigens.60,61

Intestinal Lymphangiectasia: Intestinal lymphangiectasia is characterized by dilation of intestinal lymphatics that results in protein loss as lymph leaks into the lumen of the intestine. Intestinal lymphangiectasia may be primary or secondary. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia is associated with developmental abnormalities of the intestinal lymphatics and may be associated with abnormal lymphatics elsewhere in the body. Secondary intestinal lymphangiectasia has been found in patients with diseases such as sarcoid or lymphoma that cause obstruction of the intestinal lymphatics.62 Secondary disease may also be seen when there is an increase in intralymphatic pressure because of an increase in venous pressure, such as with constrictive pericarditis; or increased right atrial pressures, such as in Fontan physiology after single ventricle repair; or congestive heart failure.59,62

Miscellaneous Protein-Losing Enteropathies: Patients with immunodeficiency syndromes may have a clinical and radiographic picture similar to that seen in patients with celiac disease. Other causes of protein-losing enteropathy include allergic gastroenteropathy, IBD, infectious mononucleosis, and polyarteritis nodosa.

Clinical Presentation

Celiac Disease: Most children affected with celiac disease come to medical attention between 4 and 24 months of age with failure to thrive, abdominal distension, and diarrhea. Diarrhea is considered one of the hallmarks of the disease, although it is not present in 10% of patients; in fact, some children may rarely come to medical attention with constipation. Children may experience anemia with iron and folate deficiency, hypertransaminemia, arthritis, and behavioral disturbances. Adolescents have delayed puberty, anorexia, and clinical findings related to the hypocalcemia and hypoproteinemia of malabsorption.59

Whipple Disease: Patients may seek medical attention with fever and extraintestinal manifestations, particularly migratory arthritis that typically involves larger joints, blood-culture negative endocarditis, central nervous system involvement, and hyperpigmentation resembling Addison disease. These findings may precede the GI manifestations.60,61

Intestinal Lymphangiectasia: Several syndromes are associated with intestinal lymphangiectasia, such as neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), Turner, Noonan, Klippel-Trénaunay, and Hennekam. Patients with either primary or secondary intestinal lymphangiectasia typically have diarrhea and edema related to hypoproteinemia, failure to thrive, and other symptoms related to malabsorption.62

Imaging

The first step in the evaluation of the patient with protein-losing enteropathy is to exclude common etiologies such as malnutrition and liver and renal disease. After excluding other causes, the diagnosis is made by documentation of enteral protein loss by determining the clearance of alpha1-antitrypsin (A1AT) from plasma.63

99m-Technetium–labeled human serum albumin (99mTc-HSA) scintigraphy has also been used to document enteral protein leakage. Because of the intermittent nature of the protein loss and the need for serial scanning for up to 24 hours, many centers now utilize A1AT testing. However, 99mTc-HSA scintigraphy has a distinct advantage of localizing the site of protein loss (i.e., large and/or small bowel or stomach).64

Classic imaging findings described on SBFT in celiac disease consist of luminal distension, thickened mucosal folds, and contrast flocculation and segmentation. The last two findings, however, are uncommonly seen with modern-day barium preparations. The mucosal folds may show reversal of the mucosal patterns of jejunum and ileum. The duodenum may exhibit mucosal erosions or thickened nodular folds. Similar thickening of small-bowel folds is seen without dilatation in Whipple disease (e-Fig. 105-11), and barium studies may also show mild bowel dilatation and thickened folds in patients with intestinal lymphangiectasia (Fig. 105-12). However, a substantial number of affected children may have normal barium examination findings.

Figure 105-12 Intestinal lymphangiectasia.

Small-bowel series in a 3-year-old girl with intestinal lymphangiectasia shows marked coarsening and thickening of the mucosal folds.

e-Figure 105-11 Whipple disease.

Upper gastrointestinal series in a 2-year-old boy with Whipple disease reveals marked thickening of the duodenal and jejunal folds.

Patients with immunodeficiency syndromes may have a clinical and radiographic picture similar to that seen in patients with celiac disease. Some affected patients have radiographic findings of lymphoid hyperplasia, particularly in the distal ileum.65

In Whipple disease, abdominal CT may show additional findings of low-density lymphadenopathy. Lymph nodes usually have a high fat content that results in a low CT attenuation value, usually between 10 and 20 Hounsfield units (HU). Hepatosplenomegaly and ascites also may be present.66

Graft-Versus-Host Disease

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) can result from hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. GVHD occurs when the donor lymphocytes react with the tissues of the host, with an inflammatory cascade that often begins in the GI tract.67,68 Three conditions are generally required for the development of GVHD: 1) the graft must contain immunologically competent cells; 2) the host must possess important transplant alloantigens that are lacking in the donor graft, so that the host appears foreign to the graft; and 3) the host must be incapable of mounting an effective immunologic reaction against the graft.69,70

Etiology

GVHD results from donor T-cell epithelial damage in the host target organs.70 Pathophysiology of GVHD includes pretransplant host tissue injury secondary to preparative ablative radiation and chemotherapy, activation of donor T-lymphocytes, and cytotoxicity against target host cells through the effected inflammatory cascade mediated through histocompatibility antigens.67,68 The most important elements in the development of GVHD relate to the degree of human leukocyte antigen mismatch.68

Clinical Presentation

Acute GVHD occurs within the first 100 days, and commonly within 30 to 40 days, after transplantation.70 Patients usually come to medical attention with a combination of dermal, hepatic, and GI abnormalities. Dermatitis is manifested as a pruritic, maculopapular rash that may proceed to desquamation. Hepatitis results from involvement of the biliary epithelium and may progress to coagulopathy, encephalopathy, and liver failure. GI manifestations include severe diarrhea, hematochezia, crampy abdominal pain, and ileus. Other organs, including the esophagus and conjunctiva, may also be involved.

Chronic GVHD is defined as occurring at or beyond 100 days after transplant, either as a de novo development or after a variable period of acute disease. The majority of patients have skin abnormalities that include desquamation and vitiligo, which may progress to scleroderma-like changes. Severe mucositis and chronic cholestatic liver disease may occur. Involvement of the hematopoietic system may lead to thrombocytopenia, and this—along with progressive onset, elevated bilirubin, and lichen planus—points to a poor prognosis.70

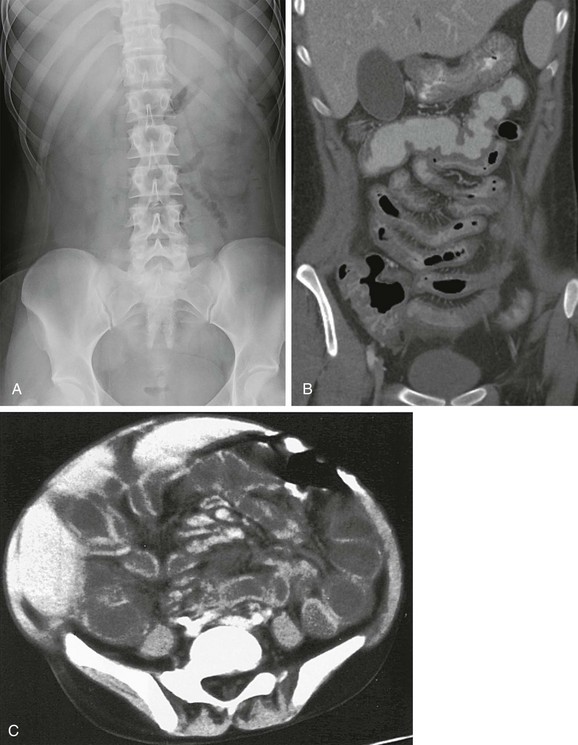

Imaging

Radiographs show a pattern of adynamic ileus with separation of bowel loops, thickening of the bowel wall, and air-fluid levels. Less commonly seen are pneumatosis intestinalis and ascites. On occasion the abdomen may be completely gasless (e-Fig. 105-13, A). Contrast studies are usually not necessary but may show severe edema of the bowel wall, with either poor or persistent coating of the mucosa. Some patients have luminal narrowing that leads to a “ribbon” or “toothpaste” appearance of the bowel loops.71,72

e-Figure 105-13 Graft versus host disease (GVHD).

A, Supine abdominal radiograph in an 18-year-old girl, who came to medical attention with voluminous watery diarrhea 95 days after unrelated-donor bone marrow transplant, shows a nonspecific paucity of bowel gas. B, Coronal contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) image demonstrates diffuse bowel wall thickening. Severe gastrointestinal GVHD was confirmed by additional clinical data. C, CT with intravenous contrast in another child with GVHD shows marked edema of the bowel wall with deep mucosal enhancement.

US reveals loss of stratification of the bowel wall, with variable mural thickening that involves both small bowel and colon.73 Doppler demonstrates a markedly hyperemic bowel wall with a “hyperdynamic” circulation as assessed by elevated velocities in the superior mesenteric artery (SMA). Supervening ischemic changes may be identified in patients with undetectable mural flow and decreased SMA velocities, which is associated with a poor prognosis.74

CT findings in GVHD can be striking (see e-Fig. 105-13, B and C). Bowel loops are variably distended with fluid, and contrast enhancement of the mucosa is marked.75 Oral contrast is poorly tolerated by these children, and positive luminal contrast actually obscures the important finding of striking mucosal enhancement.75 These findings mirror the increased flow seen on US. Engorgement of the vasa recta is the most common extraintestinal finding seen on CT and is indicative of hyperdynamic circulation. Other findings include ascites, periportal edema, pericholescystic fluid, and gallbladder wall enhancement.76

Henoch-Schönlein Purpura

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) is the most common vasculitis of childhood and affects the small vessels in the skin, joints, GI tract, and kidneys. The incidence of HSP is approximately 10 to 20 per 100,000 population and is most common in children between 2 and 6 years of age.77,78

Etiology

Pathophysiology of HSP remains incompletely understood, although it is known to represent an immune complex–mediated vasculitis with multifactorial elements that include genetic predisposition and antigenic stimulation. A significant percentage of patients have antecedent antigenic exposure to infectious agents, such as Group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus, Mycoplasma, and adenovirus, among others. Upper respiratory tract infections precede HSP in as many as 50% of cases.78

Clinical Features

Arthralgias and GI symptoms may precede the characteristic rash in 30% to 43% of patients.77 The presence of the characteristic palpable purpuric skin rash is essential for diagnosis, and it occurs along the extensor surfaces with a predilection for the lower extremities.78 GI symptoms are seen in approximately 50% to 75% of patients and include nausea, vomiting, colicky abdominal pain, and hematochezia.79 In the small intestine, the disease manifests with bleeding into the bowel wall, which can lead to enteroenteric intussusception. These most often reduce spontaneously, although this is not always the case, and complications from the intussusceptions may ensue that include ischemia of the involved bowel segment (Fig. 105-14).

Figure 105-14 Henoch-Schönlein purpura with intussusceptions.

A, Transverse sonogram of the left lower quadrant in a 6-year-old girl with acute abdominal pain reveals a thick-walled small-bowel loop with intussusception. B, Linear transducer image of the tip of the intussusception shows thick-walled bowel layers and sonolucent spaces in the intussuscepted mesentery consistent with edema. At surgery several hours later, an irreducible ileoileal intussusception was identified, which needed segmental bowel resection; the typical petechial rash appeared the following day. (Courtesy Marta Hernanz-Schulman MD, Nashville, TN)

Imaging

Cross-sectional imaging may show bowel wall thickening with skip areas of abnormality (e-Fig. 105-15); bowel dilation and mesenteric edema may also be seen.80 Findings on fluoroscopic contrast studies include segmental dilatation and stenosis, bowel wall thickening with separation of bowel loops, filling defects, and coarsening and loss of the normal mucosal fold pattern. Strictures may occur as a late sequela of the disease, likely from vasculitis with secondary focal areas of ischemia.

Treatment

GI manifestations of HSP generally require no treatment, although administration of corticosteroids has been reported to improve symptoms and shorten the symptomatic period.78,79 Patients with small bowel intussusception require monitoring, because in a minority, the intussusception may not reduce spontaneously, and obstruction and ischemia may supervene.

Small-Bowel Intussusception

Intussusceptions in young children are typically ileocolic or ileoileocolic; these are discussed in Chapter 108. Small bowel intussusceptions are more frequently identified with the widespread use of cross-sectional imaging, in which they are often an incidental finding.

Clinical Presentation

The child with small bowel obstruction may have gastroenteritis and may be imaged for abdominal pain, with the intussusception noted incidentally; these are usually transient and are not found with repeat imaging. Patients with a small bowel intussusception secondary to a lead point that does not not reduce spontaneously, present with abdominal pain and bowel obstruction.81

Imaging

As with any other intussusception, imaging findings show bowel within bowel. However, findings that indicate the presence of a transient intussusception include short length (< 3 cm), thin diameter (< 2.5 cm), and location within the small bowel. The findings are similar on US and CT (see Chapter 108, e-Fig. 108-2).81–83 Findings that suggest a pathologic phenomenon include evidence of bowel obstruction or an identifiable lead point or mesenteric nodes within the complex.

Tumors

Polyps

GI polyps in children may be a solitary and isolated finding, or they may occur in association with a polyposis syndrome. The colon is the primary site of involvement for most of the polyposis syndromes; these are reviewed in Chapter 109. One exception is Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, in which the small bowel is the most commonly involved location with hamartomatous polyps.

Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome

Overview: Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) is an autosomal-dominant syndrome with incomplete penetrance characterized by mucocutaneous pigmentation and hamartomatous polyps of the GI tract. The estimated prevalence of PJS is approximately 1 per 100,000 individuals.84

Etiology: PJS has been attributed to mutations in the STK11 gene (serine/threonine kinase 11, alias LKB1) on chromosome 19p13.3, which was identified in 1998.84

Clinical Presentation: The characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation usually precedes polyp formation and is seen in approximately 95% of patients. This pigmentation is caused by the accumulation of pigment-laden macrophages and consists of brown or black pigmentation of the lips, buccal mucosa, face, palms, and soles that typically presents during early childhood and often fades at adolescence.84

Patients with PJS have an 18-fold increased risk of malignancy compared with the unaffected population.85 Associated malignancies most commonly involve the GI tract; extraintestinal malignancies may involve the breast, pancreas, reproductive organs, and less frequently the thyroid, gallbladder, and biliary tree.85 The risk for development of malignancy in PJS patients has been estimated at 2% by age 20, steadily rising to reach 85% by age 70, with a cumulative risk of developing any malignancy estimated at 93%.84

Imaging: The polyps usually vary in size and shape and are seen in decreasing frequency in the small bowel, colon, and stomach. Polyps can be detected on SBFT and on cross-sectional imaging. They usually appear as multiple, large, pedunculated masses scattered throughout the GI tract. Diagnosis is usually made based on the combination of mucocutaneous rash and on biopsy of the polyp. Small bowel intussusceptions occurring in these patients can be easily diagnosed on US or CT, whether simple and transient, or complex (e-Fig. 105-16). Imaging can be used to diagnose and assess other malignancies associated with this condition.

e-Figure 105-16 Hamartomatous polyps causing intussusception.

Computed tomography image in a 4-year-old boy who came to medical attention with severe episodic abdominal pain shows a small bowel–small bowel intussusception with a high-grade obstruction. Infarcted hamartomatous polyps were present on the pathologic specimen of the resected intussuscepted bowel.

Treatment: Monitoring of polyp burden can be done through imaging techniques such as MRI or through capsule endoscopy, which is considered more sensitive than radiographic studies. Polypectomy can be performed endoscopically. Experimental agents for chemoprevention, such as rapamycin, are being developed and tested.84 Cancer surveillance is part of the patients’ lifelong care.

Other Benign Neoplasms

Overview: Other benign neoplasms that occur in the small intestine of children include hemangiomas, vascular malformations, neurofibromas, fibromas, leiomyomas, GI stromal tumors (GISTs), lipomas, and lipoblastomas. Most benign small-bowel tumors manifest with GI bleeding or intussusception.

Etiology: Hemangiomas can be solitary or multiple and may occur as an isolated finding or in association with a syndrome. Patients with Klippel-Trénaunay syndrome are seen with visceral and cutaneous hemangiomas. Telangiectasias, dilatated superficial blood vessels, may occur in the small intestine in Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome. Vascular malformations that involve the small intestine have also been reported in association with other soft tissue vascular malformations.86

Neurofibromas may occur in isolation or as a manifestation of NF1 and are reported to be the most frequent neoplastic lesion arising in the bowel in patients with NF1, seen in approximately 10% to 25% of patients.87

GISTs are uncommon in children; the incidence is estimated at 6.5 to 14.5 per million per year, and among these, 0.5% to 2.7% occur in patients younger than 21 years. Pediatric GISTs occur more commonly in girls.88–90 These tumors are believed to arise from the interstitial cells of Cajal and may exhibit benign or frankly malignant behavior. Although previously confused with rarer smooth muscle tumors, GISTs are differentiated from these tumors, and from neural tumors such as neurofibromas and schwannomas, by the expression of tyrosine kinase growth factor receptor (KIT, alias CD117). Whether sporadic, familial, or syndromic, GISTs are the most common mesenchymal neoplasm of the GI tract, and smooth muscle tumors, such as leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas, arise very rarely.

GISTs are associated with other syndromes, particularly NF1 but also with the Carney triad (gastric GIST, extraadrenal paraganglioma, and pulmonary chondroma), Carney-Stratakis syndrome (paragangliomas and GIST), and familial GIST.88–92

Fat-containing tumors that occur in the small intestine include lipomas and lipoblastomas. These appear primarily within the intestinal wall or in the adjacent omentum or retroperitoneum. Lipoblastomas are rare tumors related to embryonal fat, they occur almost exclusively in children, and 90% come to medical attention within the first 3 years of life.93,94

Clinical Features: Hemangiomas may manifest with GI bleeding, with obstruction as a lead point for intussusception, or perforation.86 Neurofibromas that involve the small bowel are often asymptomatic, however, they may be seen initially with GI bleeding or with obstruction secondary to intussusception or segmental volvulus.87 GISTs most frequently manifest with GI bleeding and at times with secondary anemia. Vomiting, abdominal pain, and obstruction are additional but nonspecific presenting features. Lipomas may ulcerate when larger than 2 cm and may lead to intestinal bleeding or may serve as the lead point for intussusception,95 and lipoblastomas, although benign, may recur locally in as many as 25% of cases.93

Imaging: In patients with small-bowel tumors, abdominal radiographs may reveal a mass effect, if the lesion is sufficiently large, or obstruction, if the lesion has acted as a lead point for intussusception. Fluoroscopic contrast studies may reveal a luminal filling defect or a mural mass. US may be helpful to assess for a lead point, if the lesion is complicated by intussusception. GISTs may be located external to the serosa, and the small-bowel origin may not be readily apparent; contrast attenuation may be uniform, or it may demonstrate internal areas of hemorrhage or necrosis. A similar pattern of enhancement is seen with IV gadolinium on MRI.92 Lipomas and lipoblastomas demonstrate characteristic low density on CT and fat attenuation on MR.93,95

Treatment: Neurofibromas that are symptomatic typically undergo surgical excision,96 whereas GISTs in pediatric patients tend to have an indolent course, and therapy consists of chemotherapy and evaluation for surgical resection.90 Lipoblastomas are treated by complete resection, and mesenteric lipoblastomas may require resection of adjacent intestinal loops.93,94

Malignant Tumors

With the exception of lymphoma, malignant tumors of the small intestine in children are exceedingly rare. The tumors discussed in the preceding section, such as GISTs, have both benign and malignant subgroups. Also as discussed previously, patients with PJS may develop GI malignancies. Other polyposis syndromes that largely affect the colon are further discussed in Chapter 109.

Burkitt Lymphoma

Overview: Burkitt lymphoma is the most frequent subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that occurs in children, with a median age of presentation at 8 years; more than one third of the cases occur in children between 5 and 9 years of age.97

Etiology: Burkitt lymphoma is a monoclonal B-cell lymphoma that occurs in three principal forms: endemic, sporadic, and immunodeficient. The endemic form, as initially identified in Uganda in 1958, occurs in equatorial Africa and Papua New Guinea, with a 95% association with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). The sporadic form is seen in North America, Northern and Eastern Europe, and the Far East, and its association with EBV is 15%. The immunodeficient form is associated with immune-compromised states, particularly with HIV infection, congenital deficiencies, and iatrogenic immunodeficiencies such as occur in allograft recipients.97

Clinical Presentation: GI involvement occurs in over half of pediatric patients with Burkitt lymphoma.98 Terminal ileum, cecum, and appendix are common sites of involvement by Burkitt lymphoma, with the terminal ileum being the most common location secondary to high concentration of lymphatic nodal tissue.97 Common presenting symptoms include abdominal pain or a palpable abdominal mass, followed by neck swelling.98 Patients may also come to medical attention with intestinal obstruction related to an intussusception with a pathologic lead point (see Fig. 108-7). Burkitt lymphoma is one of the most rapidly growing tumors, with a doubling time of approximately 24 hours; therefore prompt diagnosis is important.97

Imaging: Abdominal radiographs may show evidence of mass effect or obstruction related to an intussusception, or they may appear normal. SBFT may reveal a polypoid mass, strictures or areas of luminal narrowing that resemble IBD, ulceration, or an intussusception.

US in patients with lymphoma typically reveals a mass of low or heterogeneous echogenicity. A hyperechoic center that can be eccentrically positioned represents the apposed mucosal surfaces, and this may be seen when the lymphoma infiltrates the bowel wall (Fig. 105-17, A). Intussusception with a hypoechoic lead point may be the initial imaging finding.

Figure 105-17 Burkitt lymphoma.

A, Transverse abdominal sonographic image in a 12-year-old boy who presented with abdominal pain, nausea, and diarrhea shows pronounced bowel wall thickening (arrow). B, Correlative contrast-enhanced CT confirms thickening of bowel in the right lower quadrant (arrow) and moderate ascites. C, Coronal reformat again shows the involvement of the bowel with tumor (arrow) and additionally demonstrates ascites. Burkitt lymphoma was diagnosed on biopsy.

CT may also show mesenteric masses and infiltration of the bowel wall (see Fig. 105-17, B and C) with dilatation of the bowel lumen. The obstruction may be secondary to luminal narrowing or intussusception, because desmoplastic reaction is not commonly seen with Burkitt lymphoma.97 Ascites may also be present (see Fig. 105-17). The tumor may involve other abdominal sites, and careful evaluation of retroperitoneal organs, liver, and spleen is mandatory. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography may offer additional information during tumor staging.99

Carcinoid

Overview: Carcinoid is a rare neuroendocrine neoplasm that occurs in the digestive tract in up to 95% of cases.101 Most commonly found in young adults, carcinoid tumors are rare in children, with a reported prevalence of 0.08% among pediatric tumors treated at a large pediatric cancer hospital.102

Etiology: Carcinoid tumors arise from neuroendocrine enterochromaffin or Kulchitsky cells. Although most lesions arise de novo, carcinoid tumors are associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia types 1 and 2 as well as NF1.103

Clinical Presentation: Unlike the rapidly growing Burkitt lymphoma, carcinoid tumors have a slow growth rate and indolent course, with a relatively long asymptomatic period.101 Presentation may mimic acute appendicitis; patients otherwise come to medical attention with intermittent abdominal pain, vomiting, bleeding, and bowel obstruction. In adults, metastases are seen at diagnosis in approximately one fourth of patients.101 Metastases and the carcinoid syndrome are uncommon in children.102

Imaging: On abdominal radiographs, carcinoid tumors are not typically detectable unless complicated by a secondary process such as intussusception and obstruction. Rarely, a calcified appendiceal carcinoid may mimic a fecalith.103 Carcinoids may be detected on fluoroscopic contrast studies if of sufficient size. On cross-sectional imaging, associated mesenteric desmoplastic reaction or hepatic metastases may be more readily identifiable than the primary tumor. On CT, negative luminal contrast may aid in detection. On MRI, carcinoids may be seen as a subtle, asymmetric mural thickening that is isointense on T1- and mildly hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences.103

Treatment: Surgical removal is the first line of treatment for carcinoids, with additional medical treatment that combines antineoplastic chemotherapeutic agents with other agents, such as somatostatin analogs and interferon-α.103 Tumors less than 2 cm in diameter at diagnosis have a favorable prognosis.102

Ammoury, RF, Croffie, JM. Malabsorptive disorders of childhood. Pediatr Rev. 2010;31(10):407–415.

Dennehy, PH. Acute diarrheal disease in children: epidemiology, prevention, and treatment. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2005;19(3):585–602.

Jacobsohn, DA. Acute graft-versus-host disease in children. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;41(2):215–221.

Levy, AD, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: radiologic features with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2003;23(2):283–304. 456

Mattei, P, Rombeau, JL. Review of the pathophysiology and management of postoperative ileus. World J Surg. 2006;30(8):1382–1391.

Ruemmele, FM. Pediatric inflammatory bowel diseases: coming of age. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26(4):332–336.

Tolan, DJ, et al. MR enterographic manifestations of small bowel Crohn disease. Radiographics. 2010;30(2):367–384.

References

1. Rudolph, CD, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction in children: report of consensus workshop. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1997;24(1):102–112.

2. Di Lorenzo, C, Youssef, NN. Diagnosis and management of intestinal motility disorders. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2010;19(1):50–58.

3. Stehr, W, Gingalewski, C. Other causes of intestinal obstruction. In: Coran A, et al, eds. Coran: Pediatric Surgery. Philadelphia: Mosby, an Imprint of Elsevier, 2012.

4. Tsao, KJ, et al. Adhesive small bowel obstruction after appendectomy in children: comparison between the laparoscopic and open approach. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42(6):939–942. [discussion 942].

5. Welch KJ, ed. Pediatric surgery, 4th ed, Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers, 1986.

6. Katz, DA. Evaluation and management of inguinal and umbilical hernias. Pediatr Ann. 2001;30(12):729–735.

7. Brandt, ML. Pediatric hernias. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88(1):27–43. [vii-viii].

8. Lau, ST, Lee, YH, Caty, MG. Current management of hernias and hydroceles. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2007;16(1):50–57.

9. Mattei, P, Rombeau, JL. Review of the pathophysiology and management of postoperative ileus. World J Surg. 2006;30(8):1382–1391.

10. Kliegman R, Nelson WE, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 19th ed, Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders, 2011.

11. Akgur, FM, et al. Adhesive small bowel obstruction in children: the place and predictors of success for conservative treatment. J Pediatr Surg. 1991;26(1):37–41.

12. Graf, JL, et al. Pediatric hernias. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2002;23(2):197–200.

13. Boschi-Pinto, C, Velebit, L, Shibuya, K. Estimating child mortality due to diarrhoea in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(9):710–717.

14. Wilhelmi, I, Roman, E, Sanchez-Fauquier, A. Viruses causing gastroenteritis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9(4):247–262.

15. Goodgame, R. Norovirus gastroenteritis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2006;8(5):401–408.

16. Dennehy, PH. Acute diarrheal disease in children: epidemiology, prevention, and treatment. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2005;19(3):585–602.

17. Koopman, JS, et al. Patterns and etiology of diarrhea in three clinical settings. Am J Epidemiol. 1984;119(1):114–123.

18. Liacouras & Piccoli: Pediatric Gastroenterology: Requisites. Riley M, Bass D, eds. Infectious Diarrhea. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2007.

19. Hotez, PJ, et al. Helminth infections: the great neglected tropical diseases. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(4):1311–1321.

20. Miller, TL, et al. Gastrointestinal and nutritional complications of human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47(2):247–253.

21. Blakelock, RT, Beasley, SW. Infection and the gut. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2003;12(4):265–274.

22. Huang, DB, Chappell, C, Okhuysen, PC. Cryptosporidiosis in children. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2004;15(4):253–259.

23. Ebama, N, Wehbeh, W, Rubin, D. HIV Enteropathy. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2010;18:293–295.

24. Capitanio, MA, Greenberg, SB. Pneumatosis intestinalis in two infants with rotavirus gastroenteritis. Pediatr Radiol. 1991;21(5):361–362.

25. Bass, D, et al. Intestinal imaging of children with acute rotavirus gastroenteritis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;39(3):270–274.

26. Tajiri, H, et al. Abnormal computed tomography findings among children with viral gastroenteritis and symptoms mimicking acute appendicitis. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24(9):601–604.

27. Haller, JO, Cohen, HL. Pediatric HIV infection: an imaging update. Pediatr Radiol. 1994;24(3):224–230.

28. Matsumoto, T, et al. Yersinia terminal ileitis: sonographic findings in eight patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156(5):965–967.

29. Marshak, RH, Ruoff, M, Lindner, AE. Roentgen manifestations of Giardiasis. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1968;104(3):557–560.

30. Sauer, CG, Kugathasan, S. Pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: highlighting pediatric differences in IBD. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2009;38(4):611–628.

31. Carucci, LR, Levine, MS. Radiographic imaging of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2002;31(1):93–117. [ix].

32. Lee, SS, et al. Crohn disease of the small bowel: comparison of CT enterography, MR enterography, and small-bowel follow-through as diagnostic techniques. Radiology. 2009;251(3):751–761.

33. Kirks, DR, Currarino, G. Regional enteritis in children: Small bowel disease with normal terminal ileum. Pediatr Radiol. 1978;7(1):10–14.

34. Liacouras & Piccoli: Pediatric Gastroenterology: Requisites. Jacobstein D, Baldassano R, eds. Inflammatory Bowel Disease, 1st ed, Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2007.

35. Ruemmele, FM. Pediatric inflammatory bowel diseases: coming of age. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26(4):332–336.

36. Thoreson, R, Cullen, JJ. Pathophysiology of inflammatory bowel disease: an overview. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87(3):575–585.

37. Taylor, GA, et al. Plain abdominal radiographs in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Pediatr Radiol. 1986;16(3):206–209.

38. Dahnert, W. Radiology Review Manual, 5th ed. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2003.

39. Lipson, A, et al. Barium studies and ileoscopy compared in children with suspected Crohn’s disease. Clin Radiol. 1990;41(1):5–8.

40. Spalinger, J, et al. Doppler US in patients with crohn disease: vessel density in the diseased bowel reflects disease activity. Radiology. 2000;217(3):787–791.

41. Alison, M, et al. Ultrasonography of Crohn disease in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37(11):1071–1082.

42. Koo, CW, et al. Cost-effectiveness and patient tolerance of low-attenuation oral contrast material: milk versus VoLumen. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190(5):1307–1313.

43. Gaca, AM, et al. Radiation doses from small-bowel follow-through and abdomen/pelvis MDCT in pediatric Crohn disease. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38(3):285–291.

44. Toma, P, et al. CT and MRI of paediatric Crohn disease. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37(11):1083–1092.

45. Tolan, DJ, et al. MR enterographic manifestations of small bowel Crohn disease. Radiographics. 2010;30(2):367–384.

46. Fletcher, JG, et al. New concepts in intestinal imaging for inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(6):1795–1806.

47. Dillman, JR, et al. CT enterography of pediatric Crohn disease. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40(1):97–105.

48. Chalian, M, et al. MR enterography findings of inflammatory bowel disease in pediatric patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196(6):W810–W816.

49. Siddiki, HA, et al. Prospective comparison of state-of-the-art MR enterography and CT enterography in small-bowel Crohn’s disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(1):113–121.

50. Chae, EJ, et al. Radiologic and clinical findings of Behcet disease: comprehensive review of multisystemic involvement. Radiographics. 2008;28(5):e31.

51. Hiller, N, et al. Thoracic manifestations of Behcet disease at CT. Radiographics. 2004;24(3):801–808.

52. Kitaichi, N, Ohno, S. Behcet disease in children. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2008;48(3):87–91.

53. Hernanz-Schulman, M. CT as an outcome surrogate in patients with cystic fibrosis: does the effort justify the risks? Radiology. 2012;262(3):746–749.

54. Chaudry, G, et al. Abdominal manifestations of cystic fibrosis in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36(3):233–240.

55. Agrons, GA, et al. Gastrointestinal manifestations of cystic fibrosis: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1996;16(4):871–893.

56. Lardenoye, SW, et al. Appendix in children with cystic fibrosis: US features. Radiology. 2004;232(1):187–189.

57. Fields, TM, et al. Abdominal manifestations of cystic fibrosis in older children and adults. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187(5):1199–1203.

58. Robertson, MB, Choe, KA, Joseph, PM. Review of the abdominal manifestations of cystic fibrosis in the adult patient. Radiographics. 2006;26(3):679–690.

59. Ammoury, RF, Croffie, JM. Malabsorptive disorders of childhood. Pediatr Rev. 2010;31(10):407–415. [quiz 415-416].

60. Fenollar, F, Puechal, X, Raoult, D. Whipple’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(1):55–66.

61. Tan, TQ, et al. Presumed central nervous system Whipple’s disease in a child: case report. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20(4):883–889.

62. Braamskamp, MJ, Dolman, KM, Tabbers, MM. Clinical practice. Protein-losing enteropathy in children. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;169(10):1179–1185.

63. Umar, SB, DiBaise, JK. Protein-losing enteropathy: case illustrations and clinical review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(1):43–49. [quiz 50].

64. Chiu, NT, et al. Protein-losing enteropathy: diagnosis with (99m)Tc-labeled human serum albumin scintigraphy. Radiology. 2001;219(1):86–90.

65. Bastlein, C, et al. Common variable immunodeficiency syndrome and nodular lymphoid hyperplasia in the small intestine. Endoscopy. 1988;20(5):272–275.

66. Lucey, BC, Stuhlfaut, JW, Soto, JA. Mesenteric lymph nodes: detection and significance on MDCT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(1):41–44.

67. Hill, GR, Ferrara, JL. The primacy of the gastrointestinal tract as a target organ of acute graft-versus-host disease: rationale for the use of cytokine shields in allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 2000;95(9):2754–2759.

68. Jacobsohn, DA. Acute graft-versus-host disease in children. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;41(2):215–221.

69. Billingham, RE. The biology of graft-versus-host reactions. Harvey Lect. 1966;62:21–78.

70. Ferrara, JL, Deeg, HJ. Graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(10):667–674.

71. Servaes, S. Intestinal graft-versus-host disease. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40(Suppl 1):S101.

72. Jones, B, Wall, SD. Gastrointestinal disease in the immunocompromised host. Radiol Clin North Am. 1992;30(3):555–577.

73. Gorg, C, et al. High-resolution ultrasonography in gastrointestinal graft-versus-host disease. Ann Hematol. 2005;84(1):33–39.

74. Klein, SA, et al. A new approach to evaluating intestinal acute graft-versus-host disease by transabdominal sonography and colour Doppler imaging. Br J Haematol. 2001;115(4):929–934.

75. Donnelly, LF, Morris, CL. Acute graft-versus-host disease in children: abdominal CT findings. Radiology. 1996;199(1):265–268.

76. Kalantari, BN, et al. CT features with pathologic correlation of acute gastrointestinal graft-versus-host disease after bone marrow transplantation in adults. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181(6):1621–1625.

77. McCarthy, M. Report calls for changes in US global AIDS efforts. Lancet. 2007;369(9568):1155–1156.

78. Ting, TV, Hashkes, PJ. Update on childhood vasculitides. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004;16(5):560–565.

79. McCarthy, HJ, Tizard, EJ. Clinical practice: Diagnosis and management of Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;169(6):643–650.

80. Johnson, PT, Horton, KM, Fishman, EK. Case 127: Henoch-Schonlein purpura. Radiology. 2007;245(3):909–913.

81. Kim, JH. US features of transient small bowel intussusception in pediatric patients. Korean J Radiol. 2004;5(3):178–184.

82. Kornecki, A, et al. Spontaneous reduction of intussusception: clinical spectrum, management and outcome. Pediatr Radiol. 2000;30(1):58–63.

83. Strouse, PJ, DiPietro, MA, Saez, F. Transient small-bowel intussusception in children on CT. Pediatr Radiol. 2003;33(5):316–320.

84. Kopacova, M, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: diagnostic and therapeutic approach. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(43):5397–5408.

85. Buck, JL, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Radiographics. 1992;12(2):365–378.

86. Levy, AD, et al. Gastrointestinal hemangiomas: imaging findings with pathologic correlation in pediatric and adult patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177(5):1073–1081.

87. Levy, AD, et al. From the archives of the AFIP: abdominal neoplasms in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2005;25(2):455–480.

88. Benesch, M, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) in children and adolescents: A comprehensive review of the current literature. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;53(7):1171–1179.

89. Kim, SY, Janeway, K, Pappo, A. Pediatric and wild-type gastrointestinal stromal tumor: new therapeutic approaches. Curr Opin Oncol. 2010;22(4):347–350.

90. Pappo, AS, Janeway, KA. Pediatric gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2009;23(1):15–34. [vii].

91. Levy, AD, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors in patients with neurofibromatosis: imaging features with clinicopathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183(6):1629–1636.

92. Levy, AD, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: radiologic features with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2003;23(2):283–304. [456; quiz 532].

93. Kok, KY, Telisinghe, PU. Lipoblastoma: clinical features, treatment, and outcome. World J Surg. 2010;34(7):1517–1522.

94. Kucera, A, et al. Lipoblastoma in children: an analysis of 5 cases. Acta Chir Belg. 2008;108(5):580–582.

95. Thompson, WM. Imaging and findings of lipomas of the gastrointestinal tract. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(4):1163–1171.

96. Rastoqi, R. Intra-abdominal manifestations of von Recklinghausen’s neurofibromatosis. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(2):80–82.

97. Biko, DM, et al. Childhood Burkitt lymphoma: abdominal and pelvic imaging findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192(5):1304–1315.

98. Kamona, AA, et al. Pediatric Burkitt’s lymphoma: CT findings. Abdom Imaging. 2007;32(3):381–386.

99. Zeng, W, et al. Spectrum of FDG PET/CT findings in Burkitt lymphoma. Clin Nucl Med. 2009;34(6):355–358.

100. Yustein, JT, Dang, CV. Biology and treatment of Burkitt’s lymphoma. Curr Opin Hematol. 2007;14(4):375–381.

101. Barquist, E, Zinner, M. Neoplasms of the small intestine, vermiform appendix, and peritoneum. Hamilton, ON: Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine; 2000.

102. Spunt, SL, et al. Childhood carcinoid tumors: the St Jude Children’s Research Hospital experience. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35(9):1282–1286.

103. Scarsbrook, AF, et al. Anatomic and functional imaging of metastatic carcinoid tumors. Radiographics. 2007;27(2):455–477.