Acquired Esophageal Disorders

Overview

The esophagus is a muscular tube that transports food and oral secretions from the mouth to the stomach via coordinated peristalsis of striated and smooth muscle.1 A number of acquired disorders prevent the esophagus from functioning normally. These disorders generally present with symptoms such as dysphagia, food sticking, or food bolus impaction. In addition, a number of self-inflicted, accidental, or iatrogenic injuries are common in the pediatric esophagus.

Imaging

An esophagram or an upper gastrointestinal (UGI) series is the most common method used to image the esophagus directly. The two fluoroscopic studies differ in that an UGI provides a more complete evaluation of the upper gastrointestinal tract, extending from the mouth through the proximal jejunum, whereas an esophagram typically focuses on the upper gastrointestinal tract between the mouth and body of the stomach. Both studies allow the radiologist to evaluate the anatomy and function of the esophagus by watching a contrast bolus move through the esophageal lumen (see Chapter 98 for a more complete description of the technique).

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are rarely used as primary methods of imaging the esophagus; however, both CT and MRI have the advantage of allowing the radiologist to visualize the esophageal wall and lesions extrinsic to the esophagus.2 Use of cross-sectional imaging to evaluate the esophagus has several major limitations that prevent their use as a primary imaging modality: first, neither CT nor MRI provides functional information of esophageal motility; second, the esophagus is not able to be distended reliably to evaluate wall thickness accurately; third, and neither study is able to provide mucosal detail.

Gastroesophageal Reflux

Overview: GER is defined as the retrograde passage of gastric contents into the esophagus.3 When symptoms or lesions occur as a result of GER, it is referred to as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).4 The primary mechanism of GER is transient relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter. This relaxation can be triggered by vasovagal reflex initiated by gastric distension or cardiopulmonary receptors or by a swallow that does not trigger esophageal peristalsis.3 In children, severe GERD has several known risk factors, including neurologic disorders such as spastic quadriplegia and cerebral palsy, esophageal atresia, chronic lung disease such as cystic fibrosis, and hiatal hernia.5,6

Clinical Presentation: GER is ubiquitous in infants, occurring in 100% of 3-month-olds, 40% of 6-month-olds, and 5% to 20% of 1-year-olds.4,6 In children and adolescents, GERD increases in incidence with age. Symptoms of GERD are reported to occur on a weekly basis in 2% of 3- to 9-year-olds and 5% to 8.2% of children aged 10-17 years.7

The symptoms of GERD depend on age. In infants, symptoms include irritability, feeding difficulty, poor weight gain, and sleep disturbance. In older children, symptoms include heartburn, abdominal pain, regurgitation or vomiting, and dysphagia.3 Extraesophageal symptoms of GERD also can occur and include chronic cough, asthma, apnea, bradycardia, sore throat, dental erosions, and recurrent otitis or sinusitis.3 When compared with adults, children report fewer episodes of heartburn, dysphagia, and chest pain and more episodes of vomiting and regurgitation.4

GERD often is diagnosed on the basis of symptoms and a trial of acid-reduction therapy. When symptoms are not specific or are atypical, confirmatory testing can be performed. Intraesophageal pH monitoring traditionally has been thought of as the gold standard because of its ability to measure the pH in the esophagus over a long period. The main limitation of this technique is that patients may have abnormal esophageal acid exposure without symptoms of GERD or retrograde bolus movement in the esophagus.3,8 To evaluate for the retrograde passage of gastric contents and esophageal acidity, combined pH/impedance probes are used.8

Imaging: UGI imaging often is performed in the setting of GER to evaluate for an anatomic abnormality; however, it should not be used as the primary method of diagnosing GER or GERD. UGI has multiple limitations in diagnosing GER, including its nonstandard technique, lack of correlation with symptoms, and use of ionizing radiation. Methods used to provoke reflux such as the Valsalva maneuver, positional changes, abdominal compression, or leg lifting may increase the sensitivity of detecting GER but lower the specificity.3 Because more sensitive diagnostic tests are available and the radiologic findings do not correlate with symptoms, the collaborative practice guideline set forth by the American College of Radiology and the Society for Pediatric Radiology do not recommend provocative maneuvers or prolonged fluoroscopy for the detection of GER.9

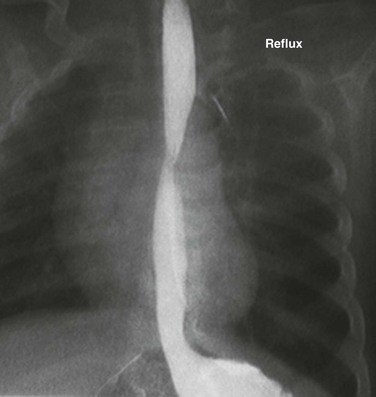

Even though UGI imaging should not be prolonged to identify GER, GER often is present (Fig. 99-1). The percentage of patients who have GER on UGI imaging decreases with age from 80% of infants <18 months to 30% of adolescents between 12 and 18 years.3 It should be noted that although the height of reflux often is reported as a surrogate for its severity, no correlation exists between the height of GER on UGI imaging and symptoms of GERD.3

Figure 99-1 Gastroesophageal reflux.

Image from an upper gastrointestinal examination shows retrograde flow of contrast from the stomach into the esophagus. Note the wide-open esophageal sphincter.

Esophageal complications of GERD include esophageal strictures and Barrett esophagitis. Esophageal strictures, also known as peptic strictures when they are caused by GERD, typically occur in the lower third of the esophagus and are a result of acidic injury. They are cited as being present in up to 15% of children with GERD and can occur at any age.10 Many patients who experience strictures have an associated comorbidity, with 25% having a neurologic impairment.10

Barrett esophagus is defined as metaplasia of cells in the distal esophagus from squamous to columnar epithelium. Its prevalence in children with GERD ranges from 0.25% to 4.8%.6,11 Risk factors for the development of Barrett esophagus in children include severe chronic GERD, congenital abnormalities, neurologic impairment, hiatal hernia, and family history.6 Although it is associated with a thirtyfold increase in esophageal adenocarcinoma in adults, the risk of developing adenocarcinoma is not defined in children.6

Treatment: Multiple options exist for treating GERD, depending on the patient’s age, comorbidities, and severity of symptoms. Generally, lifestyle changes and pharmacotherapy are first-line options. Lifestyle changes include avoidance of overfeeding, thickening feeds, upright positioning during sleep, and avoidance of second-hand smoke.3 A goal of medical therapy is to decrease the acidity of the refluxed gastric contents, which is generally performed by using proton pump inhibitors and histamine receptor antagonists.3 In patients with continued severe GERD after pharmacotherapy or other comorbidities such as neurologic impairment, antireflux surgery such as Nissen fundoplication is performed. Strictures are treated with esophageal dilation and fundoplication. In a small percentage of patients, severe and recurrent strictures will require extensive and repeated dilatations and may require surgical resection or replacement of the esophagus.10

Trauma

Ingested foreign bodies are common in children, with most occurring in children younger than 3 years.12 The American Association of Poison Control Centers reported approximately 125,000 foreign body ingestions in pediatric patients in 2009.13 This number is only a fraction of the actual number of foreign bodies ingested because it represents only the ingestions that are reported to poison control centers.

Coins

Overview: In the United States and Europe, coins are the most commonly ingested foreign body.12 It is estimated that 4% of all children swallow a coin.14 Although most coins spontaneously pass through the gastrointestinal tract, they can lodge in the esophagus. Coins typically lodge in one of three locations: the thoracic inlet (60% to 70%), the mid esophagus at the level of the aortic arch (10% to 20%), and just above the lower esophageal sphincter (20%).12

Clinical Presentation: Symptoms of chronic foreign body impaction include respiratory distress, asthma symptoms, cough, nausea, vomiting, and dysphagia. Respiratory symptoms are a result of local inflammation surrounding the foreign body.14 Patients with chronic foreign body impaction are at risk of esophageal perforation.

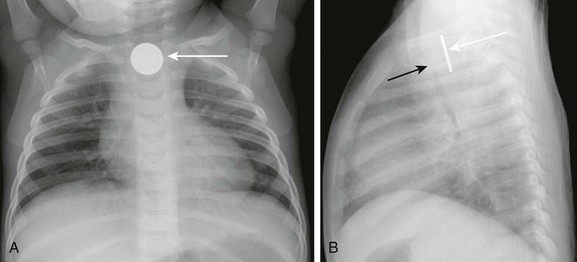

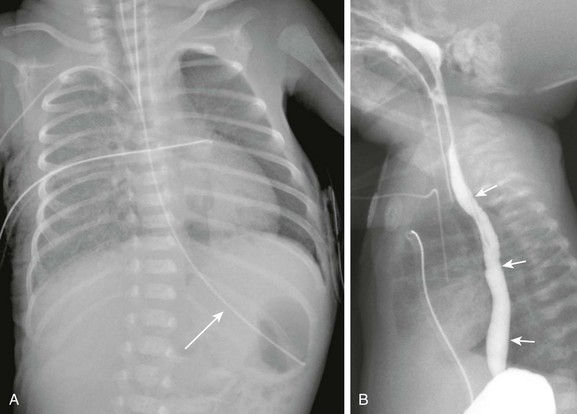

Imaging: Radiographs are useful to identify the location of the coin and to look for signs of chronic impaction. Coins generally are described as oriented in the coronal plane when they are located in the esophagus on the frontal radiograph, although reports have been made of sagittally oriented coins in the esophagus.15 Inflammatory changes that develop in patients with chronic foreign body impaction can be visualized as thickening of the space between the esophagus and trachea on lateral chest radiographs (e-Fig. 99-2, A and B); these changes therefore are useful in patients in whom the episode was not witnessed and the time course is not known. An esophagram often is performed in patients with a chronic foreign body impaction to evaluate for perforation or development of a tracheoesophageal fistula.

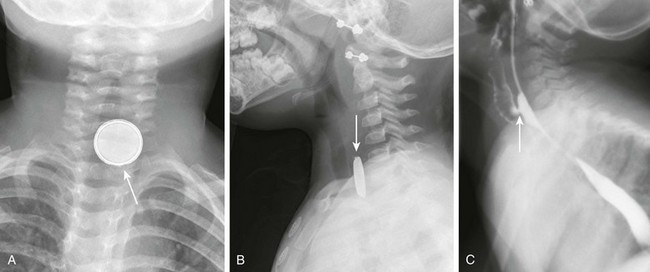

e-Figure 99-2 A swallowed coin.

A, A frontal radiograph of the chest shows a coin lodged in the proximal esophagus (arrow) at the level of the thoracic inlet. B, A lateral view of the chest shows the coin (white arrow) lodged in the proximal esophagus. The trachea (black arrow) is located anterior to the esophagus and is narrowed at the level of the foreign body. Thickening of the space between the esophagus and trachea can be seen.

Treatment: Coins, like other esophageal foreign bodies, can be removed via Foley catheter balloon extraction or endoscopy. Foley catheter extraction has been used as a safe and effective method of coin removal in children older than 1.5 years before esophageal edema has developed.16 Despite its history of safe extractions and lower cost, Foley balloon extraction has fallen from favor because of concerns about patient safety related to airway compromise or esophageal injury.17 Endoscopy is now the preferred method for extraction at most centers.

Batteries

Overview: Button battery ingestion by children is increasing in frequency.18 Button batteries often are found in objects such as watches, calculators, toys, and hearing aids. Management of battery ingestion is different than that of coins, because batteries lodged in the esophagus can cause severe damage in as little as 2 hours.18 Tissue damage is caused by one of three mechanisms: leak of alkaline contents, pressure necrosis, and generation of a current causing electrolysis of tissue fluids at the battery’s negative pole.18

Clinical Presentation: If ingestion is witnessed, extraction should occur before the development of symptoms. If symptoms develop, they include drooling, chest discomfort, choking, gagging, and airway obstruction. Damage can include esophageal perforation or creation of a fistula to the trachea or to a major blood vessel, leading to exsanguination.18

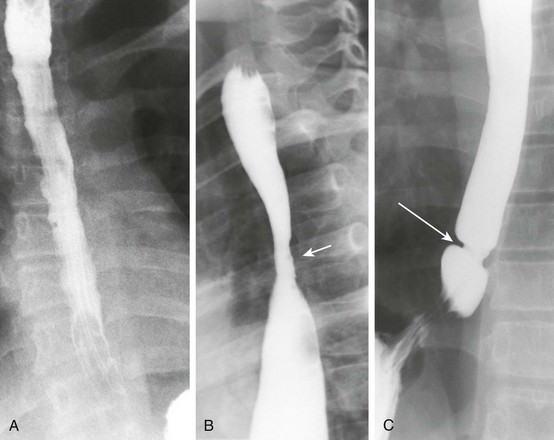

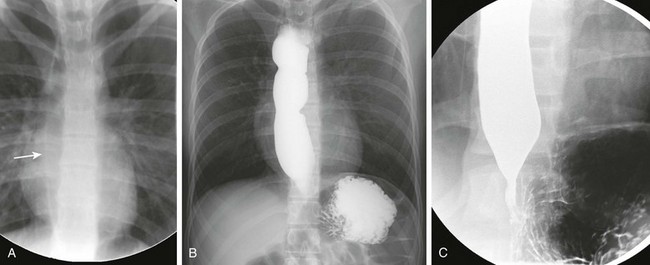

Imaging: Batteries can be distinguished on radiographs by their characteristic halo appearance with a circle of lucency just within the outer border (Fig. 99-3 and e-Fig. 99-4). An esophagram with water-soluble iso-osmolal contrast can be performed after removal to evaluate for the presence of complications, such as esophageal perforation or a tracheoesophageal fistula.

Figure 99-3 A swallowed battery.

A, A frontal radiograph of the airway shows a button battery (arrow) lodged in the proximal esophagus. The inferior margin of the battery is eroded and has an irregular edge. Note that the battery has a characteristic appearance with alternating dense and lucent bands. B, A lateral radiograph of the airway shows the button battery (arrow) lodged in the proximal esophagus. On the lateral view, the edge of the battery has a beveled appearance. C, A lateral view from an esophagram after removal of the battery shows a tracheoesophageal fistula (arrow) at the site where the battery was lodged.

e-Figure 99-4 The swallowed battery from Figure 99-3. An oblique view from the esophagram shows contrast in both the esophagus and the tracheobronchial tree as a result of the tracheoesophageal fistula.

Food Bolus Impaction

Overview: Impacted food boluses are relatively infrequent in children but may be the initial presenting symptom of eosinophilic esophagitis, peptic stricture, achalasia, vascular rings, or an extrinsic mass.19,20 Eosinophilic esophagitis is the major cause of food bolus impaction in children, accounting for >50% of all cases. The most common remaining cause of food bolus impaction in children is an area of narrowing in a patient with prior esophageal atresia repair or Nissen fundoplication surgery.21

Clinical Presentation: Acute impaction of food typically leads to symptoms of dysphagia and drooling; difficulty swallowing may lead to aspiration.

Imaging: On UGI imaging, an impacted food bolus appears as a persistent filling defect in the esophagus (Fig. 99-5). The impacted food can completely obstruct the esophagus, which is seen on UGI imaging as a standing column of contrast that does not pass beyond the food bolus.

Treatment: When a food bolus is identified, it is removed endoscopically. An esophagram can be performed after extraction or passage of the food bolus to evaluate for the underlying cause, if it is not already known. An esophageal biopsy is recommended in patients diagnosed with food bolus impaction, particularly if they do not have a history of prior esophageal surgery.

Caustic Ingestion

Overview: Ingestion of caustic materials remains relatively common in childhood. In 2009, a total of 212,263 ingestions of household cleansers were reported to the American Poison Control Centers, more than 75% of which occurred in children.13 The age group at highest risk for caustic ingestion is children younger than 5 years,13 with a peak around 2 years of age when children are learning to explore their home but are not yet able to distinguish between harmless and harmful substances.22

Whereas caustic ingestion is usually accidental in children, in adults or adolescents it is usually purposeful. The extent and severity of injury depends on several factors: the corrosiveness of the ingested substance, the quantity ingested, the physical state of the substance, the duration of the contact time of the substance with the esophagus, and subsequent secondary infection.22,23

A variety of substances can cause a caustic injury, including alkalis (pH up to 12) and acids (pH as low as 2). In contrast to acidic substances, which are sour, alkalis have a relatively innocuous taste, leading to ingestion of a greater volume.22 Further, alkaline agents produce liquefaction necrosis and rapid penetration, leading to more severe injury.23

Clinical Presentation: After caustic ingestion, patients with severe injury typically present with pain, drooling, and airway symptoms; more visible signs of tissue damage include lip swelling, mouth ulcers, and erythema of the tongue.22 Esophageal stricture is an important late complication of caustic ingestion, occurring in 2% to 63% of patients23; it can form in as little as 3 weeks after injury.24

Imaging: Initial management of patients with caustic ingestion includes a radiograph of the chest and lateral neck to evaluate for pneumomediastinum. An esophagram is not indicated in the acute phase because it delays endoscopy and does not reveal mucosal injuries.22

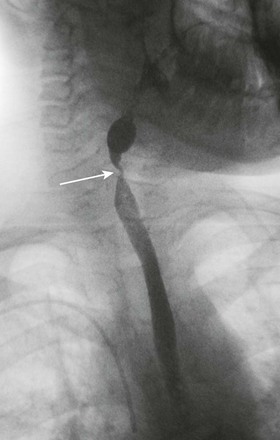

When strictures develop, they can be diagnosed on the basis of symptoms and confirmed with an esophagram (Fig. 99-6 and e-Fig. 99-7). Caustic strictures can be focal or can occupy a long segment of the esophagus depending on the substance ingested; acid ingestion typically causes a focal or short segment stricture, whereas alkali substances cause a long segment stricture.24 Strictures most commonly occur in the upper or mid esophagus. Multiple strictures also can occur.

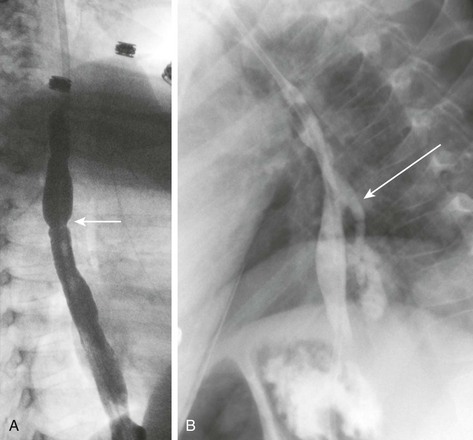

Figure 99-6 Caustic ingestion.

A, An esophagram in a patient with a recent history of lye ingestion shows an irregular contour of the esophagus and a focal area of narrowing (arrow). B, An esophagram in the same patient 3 months later and immediately after dilation of an esophageal stricture shows an esophageal perforation with leakage of contrast (arrow).

e-Figure 99-7 An esophagram in the patient shown in Figure 99-6 after the esophageal perforation had healed shows a stricture in the mid esophagus (arrow). The esophagus proximal to the stricture is dilated.

Treatment: Acutely, patients are treated with steroids, proton pump inhibitors, and antibiotics. Endoscopic evaluation is performed to assess the extent of damage and to grade the injury. Strictures are first treated with balloon dilation under fluoroscopy. The advantage of balloon dilation over dilation using a bougie is that balloons dilate strictures in a radial direction rather than in a longitudinal direction. This is thought to be less likely to cause an esophageal perforation.22 After the balloon is inflated and the waist is seen to disappear, an esophagram is performed to evaluate for a leak that occurs in 4% to 30% of patients.24 If balloon dilation fails, operative treatment with either stricture resection or esophageal replacement is performed.

Patients with a history of caustic ingestion are at risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Given this risk, these patients should undergo surveillance with endoscopy as adults.22

Pill Esophagitis

Overview: Pill esophagitis is an esophageal injury caused by medications; the drugs most frequently implicated are doxycycline and alendronate.25 Other drugs reported to cause esophageal injury include nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, potassium chloride, ferrous sulfate, phenytoin, and quinidine.25 Characteristics of medications that are more likely to cause esophageal injury include the acidity of the medication and a capsule formulation that renders it more likely to stick in the esophagus.26 Pill esophagitis is also more likely to occur in patients with delayed esophageal transit time. Factors that delay esophageal transit include taking a pill with little or no water immediately before going to bed, decreased saliva production, and anatomic areas of narrowing.26

Clinical Presentation: Patients with pill esophagitis typically present with dysphagia, odynophagia, and chest pain. Pill esophagitis often can be diagnosed by history alone.

Imaging: UGI imaging is not commonly performed due to the classic history but can show a circular area of ulceration. If endoscopy is performed, a circular ulceration is identified with normal surrounding mucosa. The ulceration typically occurs at an anatomic area of narrowing such as at the level of the aortic arch, left mainstem bronchus, or gastroesophageal junction.26

Iatrogenic Trauma

Overview: Iatrogenic trauma is the most common cause of esophageal perforation in children, representing 75% to 85% of all cases.27 Esophageal perforation can be life-threatening because the esophagus lacks a serosa. The surrounding loose areolar connective tissue is unable to prevent the spread of infection; thus oral flora and digestive enzymes are able to spread to the mediastinum.27 The most common cause of iatrogenic perforation in children is from stricture dilation. Other causes include complications of nasogastric tube placement, endotracheal intubation, endoscopy, pedicle screw placement, and sclerotherapy of esophageal varices.28–30 The typical location of perforation depends on the age of the patient. In neonates, perforation typically occurs in the cervical esophagus at the pharyngeal/esophageal junction.27

Clinical Presentation: Neonates often present after a difficult intubation with nonspecific symptoms, including drooling, choking, or coughing with feedings. In older children, perforation is more common in the thoracic esophagus. They typically present with respiratory distress, chest pain, or subcutaneous emphysema.27

Imaging: The initial diagnostic examination is often frontal and lateral radiographs of the chest. Findings on the chest radiograph include pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, and pleural effusion. If the event was caused by nasogastric tube placement, an abnormal course of the tube may be seen (e-Fig. 99-8 and Fig. 99-9).27 The location of the perforation often can be determined from the radiograph. Left-sided pneumothorax and effusion are more likely to occur in the setting of an upper thoracic perforation, whereas right-sided findings are more likely to occur with perforations in the distal esophagus.27

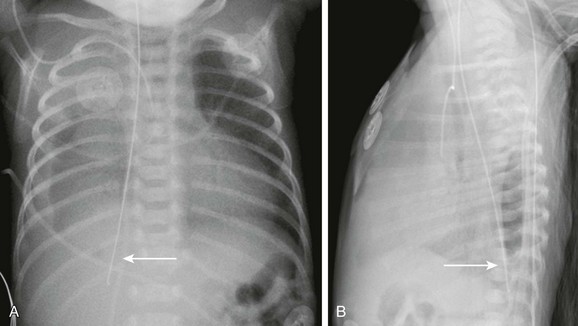

Figure 99-9 Nasogastric tube perforation.

A, A frontal radiograph of the chest in the patient shown in Figure 99-8 one day after the initial radiograph shows a new, abnormal course of the nasogastric tube (arrow). The tip of the tube is now overlies the right upper quadrant, and there is a new right pleural effusion. B, A lateral radiograph of the chest shows an abnormal posterior course of the nasogastric tube (arrow). The tip of the tube projects over the right posterior costophrenic sulcus.

e-Figure 99-8 Nasogastric tube perforation.

A, A chest radiograph in a premature infant shows a normal course of the nasogastric tube (arrow) with its tip in the stomach. B, A lateral esophagram in the same patient after replacement of the tube shows the normal course of the esophagus (arrow). Incidental nasopharyngeal reflux of contrast is seen.

UGI imaging can be useful in diagnosing and locating a perforation. If UGI is performed, water-soluble iso-osmolal contrast should be used first. If no contrast extravasation is noted, barium can then be used because it is more sensitive in the detection of an esophageal leak.27 Three patterns of perforation have been described on esophagrams: first, a local cervical leak is identified if there is a retropharyngeal pocket of contrast; a submucosal leak appears as a linear tract posterior and lateral to the esophagus; finally, free perforation appears as contrast flowing into the pleural space.27

Treatment: Treatment usually consists of expectant medical management with broad-spectrum antibiotics, pleural drainage via a chest tube, and nutritional support with total parenteral nutrition or gastrostomy; a nasogastric tube may be placed beyond the perforation under direct visualization. Operative exploration is considered in patients in whom the aforementioned more conservative management fails.27

Blunt Esophageal Trauma

Overview: The esophagus is rarely injured after chest trauma because of its flexibility and ability to decompress via the mouth and stomach.31 Reported causes of esophageal injury include handlebar injury, crush injury, opening a bottle of a carbonated drink in the mouth, and child abuse.32–35 A tracheoesophageal fistula is an even rarer complication of trauma.

Boerhaave Syndrome

Overview: Boerhaave syndrome is defined as spontaneous rupture of the esophagus, often after vomiting. The rupture typically involves the distal portion of the thoracic esophagus. Boerhaave syndrome is rare in children. When it does occur, nearly 50% of cases occur in neonates.37

Clinical Presentation: Patients typically present with vomiting, lower thoracic pain, and subcutaneous emphysema.

Imaging: In most children the rupture occurs on the right side, in contrast to adults, in whom the rupture is usually left sided,37 and therefore a chest radiograph in an infant will demonstrate a right-sided pneumothorax and pleural effusion. Diagnosis is confirmed with an esophagram and/or endoscopy; however, insufflation during endoscopy may lead to a life-threatening pneumothorax.

Treatment: Although children and neonates are more likely to have a better prognosis than adults, surgery remains the treatment of choice for persons with Boerhaave syndrome. A conservative approach can be used in patients with small tears and is used in patients with presentation or diagnosis greater than 24 hours.37

Inflammatory Conditions

Overview: Eosinophilic esophagitis is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by dense esophageal eosinophilia. During the past decade, awareness of the disease has increased along with an increase in the number of cases diagnosed. Currently it is thought that eosinophilic esophagitis occurs with an incidence of up to 1 : 10,000 children per year.38 Eosinophilic esophagitis is three to four times more common in males and can occur at any age.39 To be diagnosed with eosinophilic esophagitis, patients must have both the histologic and clinical features of the disease. Histologically, eosinophilic esophagitis is characterized by an esophageal mucosal biopsy with more than 15 eosinophils per high-power field.

Clinical Presentation: Patients present with esophageal symptoms that mimic GERD. Older children tend to present with vomiting and abdominal pain, although in infants the presentation is more likely feeding difficulties; diagnosis in infants younger than 6 months is rare. Patients often have other signs of atopy, including dermatitis, food allergies, and asthma.39

Imaging: Because the symptoms of eosinophilic esophagitis are protean and simulate those of GERD, diagnosis often is delayed. UGI frequently is performed as part of the diagnostic workup of patients because of their esophageal symptoms. On UGI imaging, the most common finding is a normal esophagus.40 The most common positive findings are GER, irregular contractions, esophageal dysmotility, esophageal strictures, esophageal rings, small caliber esophagus, and food bolus impaction (Fig. 99-10).40

Epidermolysis Bullosa

Overview: Epidermolysis bullosa is a rare group of hereditary blistering disorders caused by mutations in genes expressed at the dermal-epidermal junction. More than 100 distinct genotypes and 20 phenotypes of disease of varying severity have been described.41

Clinical Presentation: Patients often experience skin blistering and erosions with minor mechanical trauma. Repeated blistering leads to scar formation and causes symptoms such as contractures. Extracutaneous sites also can be affected and include the esophagus, bowel, rectum, anus, bladder, urethra, and trachea.41

Imaging: In the esophagus and oropharynx, scar formation leads to dysphagia and esophageal strictures. Any segment of the esophagus may be involved, although approximately half of strictures occur in the cervical esophagus.42

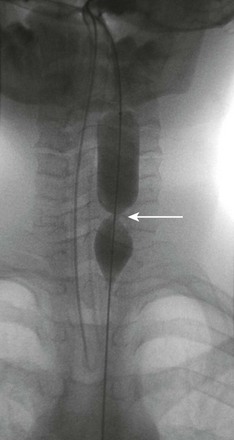

Treatment: The initial treatment of choice for esophageal strictures in children is balloon dilation under fluoroscopic or endoscopic visualization (Fig. 99-11 and e-Fig. 99-12).41,42 Patients often require multiple dilations to treat recurrent or persistent strictures.42

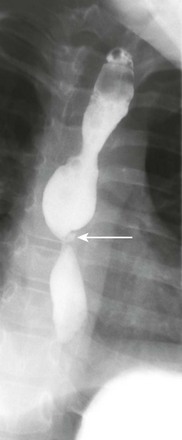

Figure 99-11 Epidermolysis bullosa.

An esophagram shows a tight stricture (arrow) in the cervical esophagus.

e-Figure 99-12 Esophageal dilation in the patient in Figure 99-11 shows a waist (arrow) in the balloon at the site of the stricture in the cervical esophagus.

Crohn Disease

Overview: Crohn disease is a chronic inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal tract characterized by waxing and waning symptoms, transmural inflammation of the bowel wall, and skip lesions. It can affect any portion of the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the anus, but it most commonly affects the small bowel and colon in children. Esophageal symptoms of Crohn disease are uncommon; however, endoscopic and histologic findings are more frequent and occur in 7.6% and 17.6%, respectively.43

Chronic Granulomatous Disease

Overview: Chronic granulomatous disease is an uncommon primary immunodeficiency characterized by recurrent bacterial and fungal infections occurring at epithelial surfaces. Gastrointestinal manifestations are present in most patients with chronic granulomatous disease. Any portion of the gastroesophageal tract may be involved from the mouth to the anus. Esophageal involvement is uncommon.

Clinical Manifestations: The symptoms overlap those of other entities affecting the esophagus and include vomiting, dysphagia, heartburn, and odynophagia.43

Behçet Syndrome

Overview: Behçet disease is an immune-mediated systemic vasculitis that affects multiple systems. It likely represents an exaggerated inflammatory endothelial response. The entity is more prevalent in Mediterranean and Middle Eastern countries, as well as Japan and Southeast Asia.

Clinical Manifestations: Behçet syndrome is a multisystem disorder characterized by pyoderma, gastrointestinal and genital mucous membrane ulceration, uveitis, and central nervous system vasculitis.47 Oral ulcerations often are the first manifestation of disease. Because these ulcerations are nonspecific, diagnosis often is delayed until abnormalities of the genitals, gastrointestinal system, or central nervous system develop. Patients also are at risk of experiencing venous thrombosis and arterial aneurysms, which can be life threatening.

Imaging: In the esophagus, dysmotility, ulceration, and stricture have been described on UGI imaging.47 These findings often are difficult to distinguish from Crohn disease. Diagnosis is made by the presence of mouth ulcers in association with two other major criteria, including skin lesions, recurrent genital ulcerations, or the presence of an excessive dermal inflammatory response termed “pathergy.”

Infectious Esophagitis

Overview: Infectious esophagitis typically is seen in immunocompromised children. Affected children may have a congenital or acquired immunodeficiency. Children receiving immunosuppressive therapy such as chemotherapy or posttransplant immunosuppression also may be affected.

Imaging: Endoscopy has replaced UGI imaging as the method of diagnosing infective esophagitis because of its ability to visualize the abnormality directly and to obtain a tissue sample for culture. If UGI is performed for infectious esophagitis, the double-contrast technique is preferred, if possible, to visualize mucosal detail.

Candida Esophagitis

Overview: Candida albicans is the most common infective agent causing esophagitis.48 Oropharyngeal candidiasis is the strongest risk factor for the development of esophagitis in patients with neutropenia or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

Imaging: On endoscopy, the appearance of esophageal candidiasis varies from a few small, raised white plaques to confluent plaques with hyperemia and ulceration.48 An esophagram is less sensitive than endoscopy in making the diagnosis.48 On esophagram, severe infection is characterized by a shaggy appearance of the esophagus as a result of multiple ulcers and nodular plaques.

Cytomegalovirus Esophagitis

Overview: Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is common in the population at large and is one of the more common opportunistic infections in immunocompromised patients. When it affects the GI tract, CMV most commonly involves the esophagus and the colon.

Clinical Manifestations: Patients with CMV involving the GI tract present with chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain, bleeding, perforation, odynophagia, peritonitis, and bowel obstruction.49

Human Immunodeficiency Virus Esophagitis

Overview: Giant esophageal ulcers can occur in patients with HIV infection. Ulcers in these patients have several different causes, including CMV, Candida albicans, mycobacteria, and herpes simplex virus.50 The ulcer is called an HIV-related or idiopathic giant ulcer when the cause of the ulcer cannot be attributed to a known pathogen.

Clinical Presentation: Patients present with esophageal symptoms of odynophagia, dysphagia, and retrosternal chest pain and may experience hematemesis. Complications include bleeding, strictures, and fistulas into the tracheobronchial tree.51

Imaging: Idiopathic giant ulcers typically occur in the middle to distal third of the esophagus. Smaller satellite ulcers also may be present.50 Idiopathic giant ulcers are difficult to distinguish from ulcers caused by CMV infection, although idiopathic giant ulcers are said to be larger and have overhanging edges.50

Tuberculosis

Overview: Involvement of the esophagus by tuberculosis is rare, occurring in 0.15% of patients. Several reports have been made of esophageal erosion with formation of a tracheoesophageal fistula in patients with tuberculosis.52,53 Esophageal perforation is thought to occur by one of three methods: rupture of a mediastinal abscess into the esophagus, formation of a traction diverticulum as a result of tuberculous mediastinitis, or erosion as a result of pressure necrosis of adjacent lymph nodes.52

Clinical Presentation: Symptoms depend on the complications; patients with esophagotracheal or esophagobronchial fistulas may experience extensive coughing after the ingestion of fluids, along with hematemesis.54

Esophageal Motility Disorders

Esophageal Atresia

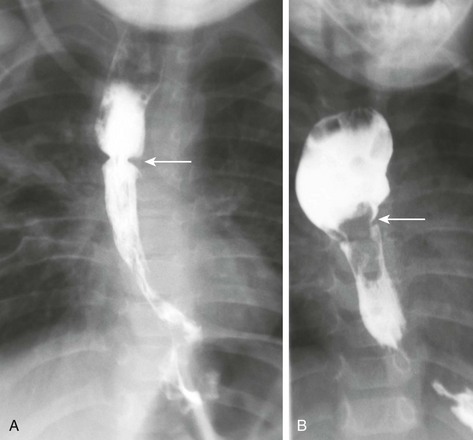

Overview: Esophageal atresia is a congenital malformation occurring in 1 in 2500 births (see Chapter 97, Congenital and Neonatal Abnormalities). It is corrected via surgical repair in the early neonatal period. The repair has several potential complications: recurrent tracheoesophageal fistula, esophageal strictures at the site of anastomosis, and food bolus impaction (Fig. 99-14).

Figure 99-14 Repaired esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula.

A, An esophagram shows a stricture (arrow) at the esophageal anastomosis site and typical dilatation of the upper esophageal pouch. B, An esophagram in a different patient shows a persistent filling defect (arrow) at the site of the esophageal anastomosis representing impacted food. The proximal esophagus is dilated as a result of a history of esophageal atresia and the partial obstruction.

Esophageal dysmotility is nearly ubiquitous in patients with a history of esophageal atresia. Two potential theories for the etiology of esophageal dysmotility have been proposed: primary dysgensis of the esophageal nerve supply, or postoperative damage to the esophageal nerve supply after the initial repair.55

Achalasia

Overview: Achalasia is a primary motor disorder characterized by failure of the lower esophageal sphincter to relax with swallowing.56 Achalasia typically presents with dysphagia, chest pain, vomiting, regurgitation, or symptoms of GER.57 Diagnosis can be made via manometry, upper endoscopy, or UGI imaging. Manometry is the gold standard for diagnosis and shows aperistalsis of the smooth muscle of the esophagus, incomplete relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter, and elevated resting pressure in the lower esophageal sphincter.58 Biopsy confirms the diagnosis of achalasia with hypertrophy of the muscularis and absent ganglion cells.

Clinical Presentation: Patients present with progressive dysphagia, regurgitation, chest pain, nocturnal cough, and heartburn.58 Aspiration pneumonia, esophageal perforation, or esophageal cancer can develop in patients with untreated achalasia.

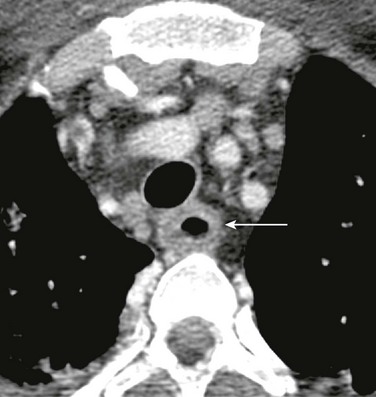

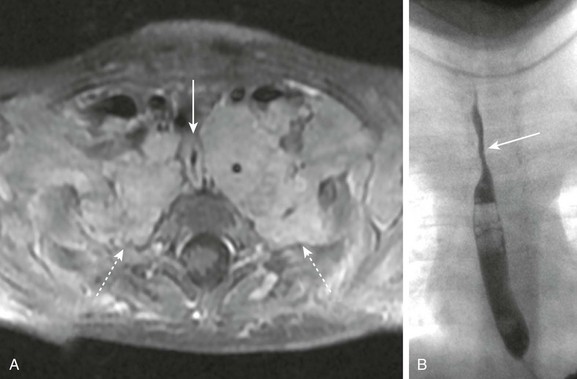

Imaging: On the chest radiograph, the esophagus can appear dilated and filled with air (Fig. 99-15). This appearance is often unusual and can mimic a medial pneumothorax. UGI imaging shows dilation of the proximal esophagus, lack of peristalsis, and smooth tapering of the distal esophagus with a bird’s beak appearance near the gastroesophageal junction.58 This appearance of the distal esophagus also can be seen on sonography58 and should be recognized if it is captured incidentally during abdominal ultrasound imaging.

Figure 99-15 Achalasia.

A, A frontal radiograph of the chest in a patient with achalasia shows a linear density representing the lateral wall of the dilated, air-filled esophagus (arrow) in the right paraspinal region. B, An overhead radiograph of the chest after completion of an esophagram shows a dilated and irregular esophagus with a narrowed gastroesophageal junction. C, A spot image from the esophagram shows the dilated distal esophagus coming to a point at the gastroesophageal junction. The distal narrowing gives the characteristic bird’s beak appearance of achalasia.

Esophageal Masses

Overview: Although they are rare, leiomyomas are the most common esophageal tumor in children. In contrast to adults, the lesions in children are more likely to be multiple or diffuse.59 Diffuse esophageal leiomyomatosis is a rare hamartomatous condition in which proliferation of the smooth muscle of the esophagus occurs. Esophageal leiomyomatosis can be associated with leiomyomas at other sites or with Alport syndrome (i.e., nephropathy, astigmatism, and myopia).60

Clinical Presentation: Isolated leiomyomas may be an incidental finding, or patients may present with progressive symptoms of dysphagia, vomiting, regurgitation, weight loss, and retrosternal pain.60

Imaging: Two potential findings on a chest radiograph are a tubular posterior mediastinal mass and rightward deviation of the azygoesophageal stripe.59,60 Findings on an esophagram can mimic achalasia and demonstrate a dilated tortuous esophagus with decreased peristalsis, tapered narrowing, and deviation from midline caused by the intramural masses.60 If cross-sectional imaging is performed, it can show diffuse circumferential wall thickening of the esophagus; a discrete soft tissue mass protruding from the esophagus also may be present.60

Malignancies

Esophageal malignancies are very rare in children. Several conditions place patients at a higher risk for malignancy, including GERD with Barrett esophagitis, caustic ingestion, and achalasia. Esophageal carcinoma is more common in certain regions of the world because of a nutritional deficiency of trace elements, consumption of pickled moldy foods, nitrosamines, and thermal injury. Areas with endemic human papilloma virus infection also have a higher incidence of esophageal carcinoma.61

Extraesophageal tumors can abut the esophagus. The most common thoracic tumors to affect the esophagus are thoracic neuroblastomas and plexiform neurofibromas62 (Figs. 99-16 and 99-17). These tumors can cause mass effect on the esophagus but rarely invade it. Depending on the degree of mass effect, the patient can present with dysphagia.

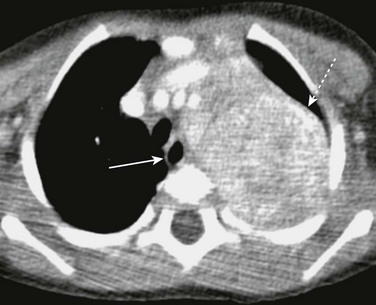

Figure 99-16 Neuroblastoma.

Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography shows a large, partially calcified left paraspinal neuroblastoma (dashed arrow) displacing the esophagus (arrow) toward the right.

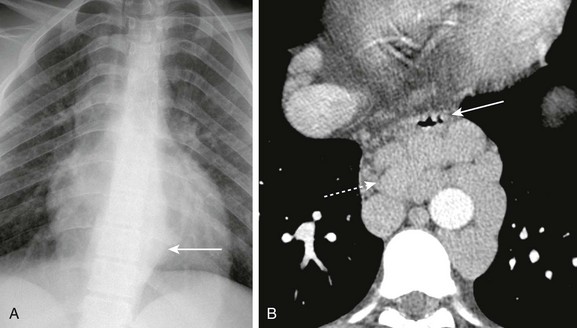

Figure 99-17 Neurofibromatosis.

A, T1-weighted postcontrast image of the upper chest in a patient with type 1 neurofibromatosis show bilateral plexiform neurofibromas (dashed arrows) occupying the lung apices and extending to the axillae. The masses are compressing the esophagus (arrow). B, An esophagram in the same patient shows narrowing of the proximal esophagus (arrow) as it passes between the plexiform neurofibromas; the density from the masses extending to the thoracic apices also can be appreciated.

Other Esophageal Lesions

Overview: Esophageal varices are seen in the setting of portal hypertension. Varices primarily occur around the esophagus, stomach, spleen, and retroperitoneum. When portal hypertension is suspected, endoscopy is the best method to screen for varices.

Clinical Presentation: Patients present with symptoms of portal hypertension; varices themselves are silent until an episode of bleeding ensues. Variceal bleeding is the most serious complication of portal hypertension and is associated with a mortality of up to 30%.63

Imaging: Varices can be identified on contrast-enhanced CT as dilated serpiginous vessels (Fig. 99-18). On UGI imaging, they appear as a lobulated filling defect in the distal esophagus.

Figure 99-18 Portal hypertension and esophageal varices.

A, A frontal radiograph of the chest in a patient with portal hypertension shows a soft tissue mass (arrow) in the left paraspinal region. B, Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography in the same patient shows multiple dilated paraesophageal varices (dashed arrow) displacing the esophagus anteriorly (arrow).

Plummer-Vinson Syndrome

Overview: Plummer-Vinson syndrome is an uncommon disease that typically occurs in middle-aged white women, although it can occur in the pediatric age group.

Clinical Presentation: Plummer-Vinson syndrome is characterized by dysphagia, iron deficiency anemia, and esophageal webs. It is associated with celiac disease and increased menstrual blood loss.67

Boyle, JT. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in 2006. The imperfect diagnosis. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36(suppl 2):192–195.

Callahan, MJ, Taylor, GA. CT of the pediatric esophagus. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:1391–1396.

Fordham, LA. Imaging of the esophagus in children. Radiol Clin North Am. 2005;43:283–302.

Staton, RJ, Williams, JL, Arreola, MM, et al. Organ and effective doses in infants undergoing upper gastrointestinal (UGI) fluoroscopic examination. Med Phys. 2007;34:703–710.

References

1. Fordham, LA. Imaging of the esophagus in children. Radiol Clin North Am. 2005;43(2):283–302.

2. Callahan, MJ, Taylor, GA. CT of the pediatric esophagus. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181(5):1391–1396.

3. Boyle, JT. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in 2006. The imperfect diagnosis. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36(suppl 2):192–195.

4. Hoffman, I, De Greef, T, Haesendonck, N, et al. Esophageal motility in children with suspected gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50(6):601–608.

5. Gilger, MA, El-Serag, HB, Gold, BD, et al. Prevalence of endoscopic findings of erosive esophagitis in children: a population-based study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;47(2):141–146.

6. Jeurnink, SM, van Herwaarden-Lindeboom, MY, Siersema, PD, et al. Barretts esophagus in children: Does it need more attention? Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43(9):682–687.

7. Nelson, SP, Chen, EH, Syniar, GM, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux during childhood: a pediatric practice-based survey, Pediatric Practice Research Group. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154(2):150–154.

8. Woodley, FW, Mousa, H. Acid gastroesophageal reflux reports in infants: a comparison of esophageal pH monitoring and multichannel intraluminal impedance measurements. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51(11):1910–1916.

9. American College of Radiology and Society for Pediatric Radiology. 2010 ACR-SPR practice guideline for the performance of contrast esophagrams and upper gastrointestinal examinations in infants and children (PDF file). http://www.acr.org/~/media/A77716DEDE5C486EA73F2249D578FD39.pdf. [Accessed August 20, 2012].

10. Pearson, EG, Downey, EC, Barnhart, DC, et al. Reflux esophageal stricture—a review of 30 years experience in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45(12):2356–2360.

11. El-Serag, HB, Gilger, MA, Shub, MD, et al. The prevalence of suspected Barretts esophagus in children and adolescents: a multicenter endoscopic study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64(5):671–675.

12. Kay, M, Wyllie, R. Pediatric foreign bodies and their management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2005;7(3):212–218.

13. Bronstein, AC, Spyker, DA, Cantilena, LR, Jr., et al. 2009 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers National Poison Data System (NPDS): 27th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2010;48(10):979–1178.

14. Miller, RS, Willging, JP, Rutter, MJ, et al. Chronic esophageal foreign bodies in pediatric patients: a retrospective review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;68(3):265–272.

15. Schlesinger, AE, Crowe, JE. Sagittal orientation of ingested coins in the esophagus in children. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196(3):670–672.

16. Towbin, R, Lederman, HM, Dunbar, JS, et al. Esophageal edema as a predictor of unsuccessful balloon extraction of esophageal foreign body. Pediatr Radiol. 1989;19(6-7):359–360.

17. Little, DC, Shah, SR, St Peter, SD, et al. Esophageal foreign bodies in the pediatric population: our first 500 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41(5):914–918.

18. Litovitz, T, Whitaker, N, Clark, L. Preventing battery ingestions: an analysis of 8648 cases. Pediatrics. 2010;125(6):1178–1183.

19. Lao, J, Bostwick, HE, Berezin, S, et al. Esophageal food impaction in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2003;19(6):402–407.

20. Underberg-Davis, S, Levine, MS. Giant thoracic osteophyte causing esophageal food impaction. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;157(2):319–320.

21. Diniz, LO, Towbin, AJ. Causes of esophageal food bolus impaction in the pediatric population. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57(3):690–693.

22. Riffat, F, Cheng, A. Pediatric caustic ingestion: 50 consecutive cases and a review of the literature. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22(1):89–94.

23. Dogan, Y, Erkan, T, Cokugras, FT, et al. Caustic gastroesophageal lesions in childhood: an analysis of 473 cases. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2006;45(5):435–438.

24. Youn, BJ, Kim, WS, Cheon, JE, et al. Balloon dilatation for corrosive esophageal strictures in children: radiologic and clinical outcomes. Korean J Radiol. 2010;11(2):203–210.

25. Glenn, SM, Parakh, K. Education and imaging. Gastrointestinal: pill esophagitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23(2):339.

26. Grochenig, HP, Tilg, H, Vogetseder, W. Clinical challenges and images in GI. Pill esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(4):996. [1365].

27. Gander, JW, Berdon, WE, Cowles, RA. Iatrogenic esophageal perforation in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 2009;25(5):395–401.

28. Emil, SG. Neonatal esophageal perforation. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39(8):1296–1298.

29. Iqbal, CW, Askegard-Giesmann, JR, Pham, TH, et al. Pediatric endoscopic injuries: incidence, management, and outcomes. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43(5):911–915.

30. O’Brien, JR, Krushinski, E, Zarro, CM, et al. Esophageal injury from thoracic pedicle screw placement in a polytrauma patient: a case report and literature review. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20(6):431–434.

31. Moore, MA, Wallace, EC, Westra, SJ. The imaging of paediatric thoracic trauma. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39(5):485–496.

32. Ablin, DS, Reinhart, MA. Esophageal perforation with mediastinal abscess in child abuse. Pediatr Radiol. 1990;20(7):524–525.

33. John, V, Mathai, J, Chacko, J, et al. Tracheoesophageal fistula in a child after blunt chest trauma. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41(10):E27–E29.

34. Meyerovitch, J, Ben Ami, T, Rozenman, J, et al. Pneumatic rupture of the esophagus caused by carbonated drinks. Pediatr Radiol. 1988;18(6):468–470.

35. Mukherjee, K, Isbell, JM, Yang, E. Blunt posterior tracheal laceration and esophageal injury in a child. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44(6):1292–1294.

36. Jacob, R, Kunder, S, Mathai, J, et al. Traumatic tracheoesophageal fistula in a 5-year old. Paediatr Anaesth. 2006;16(10):1068–1072.

37. Antonis, JH, Poeze, M, Van Heurn, LW. Boerhaaves syndrome in children: a case report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41(9):1620–1623.

38. Noel, RJ, Putnam, PE, Rothenberg, ME. Eosinophilic esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(9):940–941.

39. Putnam, PE, Rothenberg, ME. Eosinophilic esophagitis: concepts, controversies, and evidence. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2009;11(3):220–225.

40. Diniz, LO, Putnam, PE, Towbin, AJ. Fluoroscopic findings in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Pediatr Radiol. 2012;42(6):721–727.

41. Gottschalk, A, Venherm, S, Vowinkel, T, et al. Anesthesia for balloon dilatation of esophageal strictures in children with epidermolysis bullosa dystrophica: from intubation to sedation. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2010;23(4):518–522.

42. Fine, JD, Johnson, LB, Weiner, M, et al. Gastrointestinal complications of inherited epidermolysis bullosa: cumulative experience of the National Epidermolysis Bullosa Registry. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46(2):147–158.

43. Ramaswamy, K, Jacobson, K, Jevon, G, et al. Esophageal Crohn disease in children: a clinical spectrum. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;36(4):454–458.

44. Rahhal, RM, Banerjee, S, Jensen, CS. Pediatric Crohn disease presenting as an esophageal stricture. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45(1):125–129.

45. Towbin, AJ, Chaves, I. Chronic granulomatous disease. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40(5):657–668. [quiz 792-793].

46. Vlymen, WJ, Moskowitz, PS. Roentgenographic manifestations of esophageal and intestinal involvement in Behçets disease in children. Pediatr Radiol. 1981;10(4):193–196.

47. Bang, D. Treatment of Behçets disease. Yonsei Med J. 1997;38(6):401–410.

48. Chiou, CC, Groll, AH, Gonzalez, EC, et al. Esophageal candidiasis in pediatric acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: clinical manifestations and risk factors. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19(8):729–734.

49. Ukarapol, N, Chartapisak, W, Lertprasertsuk, K, et al. Cytomegalovirus-associated manifestations involving the digestive tract in children with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;35(5):669–673.

50. Blitman, NM, Ali, M. Idiopathic giant esophageal ulcer in an HIV-positive child. Pediatr Radiol. 2002;32(12):907–909.

51. Epstein, DP, Locketz, M. Oesophageal ulceration in HIV-infected patients. S Afr Med J. 2009;99(2):107–109.

52. Erlank, A, Goussard, P, Andronikou, S, et al. Oesophageal perforation as a complication of primary pulmonary tuberculous lymphadenopathy in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37(7):636–639.

53. Goussard, P, Andronikou, S. Tuberculous broncho-oesophageal fistula: images demonstrating the pathogenesis. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40(suppl 1):S78.

54. Lucaya, J, Solé, S, Badosa, J, et al. Bronchial perforation and bronchoesophageal fistulas: tuberculous origin in children. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1980;135(3):525–528.

55. Lilja, HE, Wester, T. Outcome in neonates with esophageal atresia treated over the last 20 years. Pediatr Surg Int. 2008;24(5):531–536.

56. Lee, CW, Kays, DW, Chen, MK, et al. Outcomes of treatment of childhood achalasia. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45(6):1173–1177.

57. Jung, C, Michaud, L, Mougenot, JF, et al. Treatments for pediatric achalasia: Heller myotomy or pneumatic dilatation? Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2010;34(3):202–208.

58. Iacob, D, Fufezan, O, Farcau, D, et al. Clinical and ultrasound approach to achalasia in a child. Case report. Med Ultrason. 2010;12(1):66–70.

59. Guest, AR, Strouse, PJ, Hiew, CC, et al. Progressive esophageal leiomyomatosis with respiratory compromise. Pediatr Radiol. 2000;30(4):247–250.

60. Gupta, V, Lal, A, Sinha, SK, et al. Leiomyomatosis of the esophagus: experience over a decade. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13(2):206–211.

61. Khurshed, A, Ahmed, R, Bhurgri, Y. Primary gastrointestinal malignancies in childhood and adolescence—an Asian perspective. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2007;8(4):613–617.

62. Retrosi, G, Nanni, L, Ricci, R, et al. Plexiform schwannoma of the esophagus in a child with neurofibromatosis type 2. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44(7):1458–1461.

63. Mileti, E, Rosenthal, P. Management of portal hypertension in children. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2011;13(1):10–16.

64. Heinen, FL, Vallone, P, Elmo, G. Esophageal diverticulum in an infant with Downs syndrome and type III esophageal atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38(4):E9.

65. Herman, TE, McAlister, WH. Esophageal diverticula in childhood associated with strictures from unsuspected foreign bodies of the esophagus. Pediatr Radiol. 1991;21(6):410–412.

66. Toyohara, T, Kaneko, T, Araki, H, et al. Giant epiphrenic diverticulum in a boy with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Pediatr Radiol. 1989;19(6-7):437.

67. Novacek, G. Plummer-Vinson syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1:36.