Acquired Diseases of the Thoracic Great Vessels

Acquired Diseases of the Thoracic Aorta

Pathology of the aorta can be categorized into aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection, and aortic stenosis.1 Although each aortic disease may present one or more of these manifestations, it is the clinical consequences of aneurysm, dissection, or stenosis that determine mortality and morbidity (Table 83-1).

Table 83-1

Principal Etiologies of Acquired Aortic Diseases

| Manifestation | Causes |

| Aortic aneurysm | Infectious aortitis |

| Inflammatory aortitis | |

| Takayasu syndrome (acute, chronic) | |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | |

| Sarcoid | |

| Connective tissue disease | |

| Marfan syndrome | |

| Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (vascular type) | |

| Loeys-Dietz syndrome | |

| Arterial tortuosity syndrome | |

| Neurocutaneous disease | |

| Tuberous sclerosis | |

| Trauma or postsurgical (pseudoaneurysm) | |

| Aortic dissection | Connective tissue disease |

| Marfan syndrome | |

| Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (vascular type) | |

| Trauma | |

| Aortic stenosis | Inflammatory aortitis |

| Takayasu syndrome (chronic) | |

| Congenital rubella syndrome | |

| Radiation | |

| Neurocutaneous disease | |

| Neurofibromatosis (type I) | |

| PHACES syndrome | |

| Postsurgical | |

| Coarctation repair | |

| Aortopulmonary shunts |

Normally, the caliber of the aorta gradually decreases in size from the sinotubular junction to the aortic hiatus. An aortic aneurysm is defined as an abnormal dilation of the aorta, which may undergo progressive expansion. An aortic aneurysm may form if wall stress increases, as in the case of systemic hypertension, or if the aortic wall weakens, as in the case of Marfan syndrome (see Chapter 79). The expansion rate of an aneurysm is determined by the wall stress, which increases with diameter. Thus a large aneurysm is more likely to expand than a small aneurysm, and the expansion is an accelerating process until rupture occurs.

Trauma

Overview: Trauma is a major cause of death in children and results primarily from motor vehicle accidents, although firearm injury (Fig. 83-1) and child abuse are other important causes of traumatic death. Survival of a child with a traumatic aortic injury until arrival at the emergency department is rare, accounting for one to two cases per year at large metropolitan level I pediatric trauma centers. Operative treatment involves fewer than 0.14% of all trauma patients, and only 6% of all traumatic ruptures of the aorta occur in patients younger than 16 years.2,3 The outcome of traumatic aortic injury in the pediatric population is directly related to timely diagnosis, proper treatment, and hemodynamic status at the time of presentation.

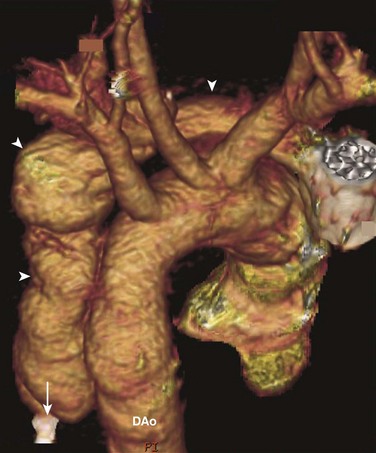

Figure 83-1 An aortic false aneurysm from a gunshot wound in an 18-year-old man.

Volume rendering of a computed tomography angiogram shows a false aneurysm (arrowheads) that follows the track of a bullet. The bullet first entered the chest horizontally, parallel to the aortic arch, rupturing the aorta. Then it was deflected downward and came to rest (arrow) adjacent to the descending aorta (DAo).

Imaging: Chest radiographic findings such as pleural capping at the left lung apex, obscuration of the aortic arch, mediastinal widening, pleural effusion, pneumothorax, pulmonary contusion, tracheal and nasogastric tube deviation, and upper rib and clavicle fracture in the setting of blunt trauma should raise clinical suspicion for an aortic injury (Fig. 83-2). Historically, the definitive diagnosis of traumatic aortic injury was made by conventional catheter angiography. Today, computed tomographic angiography (CTA) has supplanted catheter angiography as the diagnostic method of choice.4,5 CTA allows speedy and precise visualization of the traumatic aortic injury. Care should be taken to identify the location of aortic rupture, active extravasation of arterial contrast, a dissection flap extending to major aortic branches, hemothorax and hemopericardium, and other organ and musculoskeletal injuries.

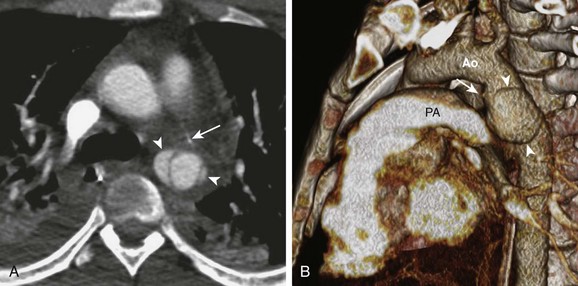

Figure 83-2 Aortic rupture in a 16-year-old boy as a result of a motor vehicle accident.

A, An axial image from a computed tomography (CT) angiogram shows a ruptured descending aorta at the level of the ligamentum arteriosum (arrow) and two pseudoaneurysms (arrowheads) extending beyond the aortic wall. B, A volume-rendered image of the CT angiogram shows the relationship between one of the pseudoaneurysms (arrowheads) and the ligamentum arteriosum (arrow) between the aorta (Ao) and the pulmonary trunk (PA).

Treatment and Imaging Follow-up: The goals of treatment of pediatric traumatic aortic rupture are identical to those in adults. The mainstay of treatment is operative repair of the aorta.6 Patients for whom surgery poses a high risk have been treated successfully with endovascular stent grafts, with deployment during adenosine-induced cardiac arrest. CTA should be performed immediately after stent placement, with a follow-up study in 48 hours to document the stability of the repair. Rarely, observational management for an intimal tear has been utilized in patients with comorbidities too severe to allow intervention.

Acquired Diseases of the Pulmonary Artery

Overview: Pulmonary embolism (PE) is an uncommon but potentially fatal disease in children.7 In pediatric patients with deep venous thrombosis and PE, the mortality rate from all causes has been reported to be as high as 16%, whereas the mortality rate directly attributable to deep venous thrombosis or PE was 2.2%.8 The most common risk factor for PE in children is catheter thrombosis, which develops in as many as 50% of patients with central venous catheters.9 Other risk factors are peripartum asphyxia, dehydration, septicemia, trauma and burns, surgery, hemolysis, malignancy, and renal disease such as nephrotic syndrome. Rarely, PE can be seen in the setting of intracranial venous sinus thrombosis and Klippel-Trénaunay syndrome. Abnormal coagulation factors associated with adult PE that also have been reported in children are antiphospholipid antibodies, factor V Leiden mutation, and deficiencies in protein S, protein C, and antithrombin III.10

Imaging: Traditionally, catheter pulmonary angiography was considered the diagnostic gold standard.11 In current clinical practice, catheter pulmonary angiography has been replaced by noninvasive CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) performed with high-speed multidetector CT. The accuracy of the detection of PE by CTPA in an adult population has been studied in the Prospective Investigation of Pulmonary Embolism Diagnosis II trial.12 With use of CT technology available before 2003, the sensitivity and specificity in this trial were reported as 83% and 96%, respectively. With advances in CT technology in the past decade that have improved spatial resolution, increased scan speed, and reduced contrast dose and radiation exposure, the diagnostic accuracy for PE likely is improved. Other imaging methods include nuclear ventilation-perfusion scanning and magnetic resonance pulmonary angiography.

As in adult patients, CTPA increasingly is being used to diagnose PE in children (Fig. 83-3), although its accuracy in children has not been studied by rigorous clinical trials. CTPA in children is technically challenging because of the small size of their pulmonary arteries, their inability to cooperate in holding their breath, and concerns about radiation exposure. The principal strategy for reducing radiation dose is to lower exposure factors such as x-ray tube voltage and tube current. Both maneuvers increase image noise and confound visual detection of PE. As a result, the CTPA protocol for children requires meticulous attention to optimize spatial resolution, scan speed, and exposure factors.

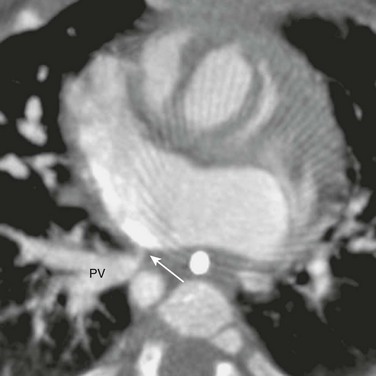

Figure 83-3 A saddle pulmonary embolus in a 15-year-old girl who recently started taking oral contraceptive pills.

A filling defect spanning the left and right main pulmonary arteries is a large pulmonary embolism. A peripheral consolidation (arrow) that developed 2 days after her acute symptom is a pulmonary infarction.

Treatment and Follow-up: Anticoagulation is the mainstay of medical therapy for persons with a PE. Thrombolytic therapy is reserved for persons with hemodynamic instability. Surgical pulmonary thrombectomy has been successfully performed in persons with central or saddle emboli.

PE can be caused by materials other than bland thrombus. Septic emboli can be the result of endocarditis and of thrombophlebitis. Lemierre syndrome describes jugular vein thrombosis associated with anaerobic infection of the head and neck (classically by Fusobacterium necrophorum), and more than 50% of these cases are complicated by septic emboli to the lungs.13 Tumor emboli may come from Wilms tumor, neuroblastoma, and hepatocellular carcinoma, because occasionally these tumors invade the inferior vena cava. Rarely, tumor emboli originate from primary cardiac tumors, such as atrial myxomas. Foreign bodies that embolize to the lungs include broken catheter tips and guide wires, misplaced embolization coils, and other endovascular devices. Finally, fat emboli may occur after major orthopedic trauma or surgery. In these situations, CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may help locate the source of emboli.

Acquired Diseases of the Venae Cavae

Overview: SVC syndrome (SVCS) is a clinical manifestation of gradual obstruction of SVC flow, leading to elevated central venous pressure of the upper extremities and the head, interstitial edema and swelling of the upper body, and development of venous collaterals to the inferior vena cava (IVC). In children, SVCS is a medical emergency because swelling of the neck can compress and obstruct their small airway more easily than in adults. The most common pediatric cause of SVCS is extrinsic compression of the SVC by non-Hodgkin lymphoma.14 The SVC can be compressed by other mediastinal masses, including germ cell tumor, infectious lymphadenopathy, aortic aneurysm, and mediastinal fibrosis.15 Luminal occlusion (Fig. 83-4) can be the result of a thrombus forming around a central venous catheter or pacemaker wires, or of venous thrombosis secondary to Behçet syndrome (see Chapter 82). Intrinsic stenosis of the SVC can be caused by scarring from a chronic indwelling catheter and by infusion of caustic agents. Finally, SVC flow may be obstructed within the atrial baffle after the atrial switch procedure or the Mustard-Senning procedure16 (see Chapter 76). Obstruction of the SVC above the azygos return precludes decompression by retrograde flow into the azygos vein and leads to more severe symptoms.

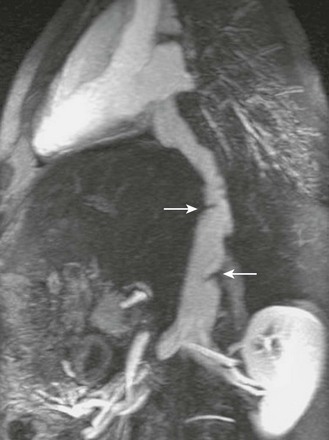

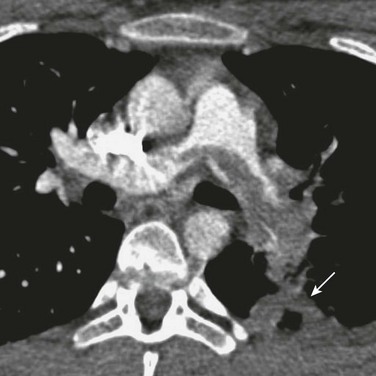

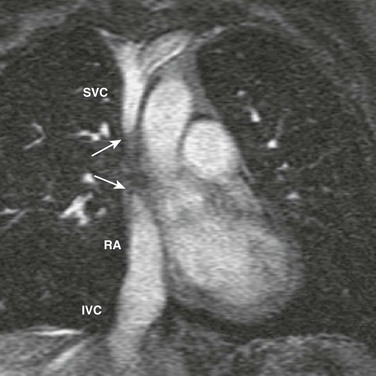

Figure 83-4 Superior vena cava (SVC) occlusion in a 14-year-old girl who had a long-term central venous catheter placed in the SVC.

Coronal reconstruction of a magnetic resonance angiogram shows a complete obstruction (arrows) between the SVC and the right atrium (RA), whereas the inferior vena cava (IVC) drains freely into the RA.

Imaging and Treatment: The gold standard for the diagnosis of SVCS is catheter venography, with which the level of SVC obstruction, the presence of venous collaterals, and the central venous pressure can be assessed. Noninvasive tomographic techniques such as CT and MR venography can define the SVC stenosis and are helpful in evaluating any extrinsic mass.17 An advantage of MRI is that venography can be done without use of a contrast agent through use of phase-contrast or time-of-flight inflow enhancement techniques. Treatment of SVCS depends on the underlying cause. Radiation or chemotherapy that reduces the tumor size may relieve the SVC obstruction. Thrombosed central venous catheters should be removed. Residual thrombosis may be treated with selective thrombolysis, and residual stenosis may be stented.

Inferior Vena Cava Obstruction

Overview: Reasons for acquired obstruction of the IVC are similar to those of the SVC. Thrombosis of the IVC can be the result of catheter access, placement of a caval filter, severe illness including sepsis and dehydration, and other hypercoagulopathy. The IVC can be obstructed at its entrance to the right atrium by abdominal tumors, such as Wilms tumor, neuroblastoma, hepatoblastoma, and hepatocellular carcinoma. The Budd-Chiari syndrome classically is attributed to hepatic venous obstruction, but the intrahepatic portion of the IVC can be involved, resulting in symptoms of hepatomegaly, ascites, and abdominal pain (Fig. 83-5).18 Obstruction is caused by thrombus or an IVC web.

Imaging and Treatment: Imaging evaluation can be performed with abdominal ultrasound, CT, and MRI, with the investigation focused on the location and severity of the obstruction and on the presence of a thrombus or extrinsic mass. Treatment is directed to correcting the underlying conditions. In the short term, patency of the IVC can be maintained with an endovascular stent.

Superior Vena Cava Aneurysm

Overview: Although a true SVC aneurysm is very rare, dilation of the SVC is more commonly seen in persons with elevated central venous pressure as a result of right heart failure or severe tricuspid valve regurgitation.19 Dilation of the SVC also is associated with mediastinal lymphatic malformation, although the pathophysiology is not known.20 Patients with saccular SVC aneurysms may be at risk for SVC thrombosis and PE.

Acquired Disease of the Pulmonary Veins

Overview: Acquired pulmonary vein stenosis in children is uncommon but can be seen in children with complications of surgical repair of congenital pulmonary vein anomalies. Children who undergo repairs for total anomalous pulmonary venous connection (Fig. 83-6) and scimitar syndrome are at increased risk for acquired pulmonary vein stenosis. Pulmonary vein stenosis develops in up to 10% of infants who undergo repair of total anomalous pulmonary venous connection21; these patients often are very ill from pulmonary edema and poor oxygen saturation, with a mortality rate as high as 50%. The prognosis is worse for patients who have coexisting complex cardiac anomalies, often as part of the heterotaxy syndrome. Other acquired causes of pulmonary vein stenosis include mediastinal fibrosis and extrinsic compression by mediastinal tumors.

Imaging and Treatment: Catheter angiography is used to define the location of the pulmonary venous obstruction, and the severity of the stenosis can be evaluated by measuring the pressure gradient across the stenosis. With three-dimensional imaging capability, CTA and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) often can identify the obstruction better than catheter angiography. CTA has the added advantage of evaluating the pulmonary parenchyma and airways for additional complications.

Pulmonary vein stenosis has been treated with angioplasty, endovascular stent placement, and surgical repair.21,22 Despite immediate postoperative success, restenosis often occurs, and mortality is not substantially improved. The pathophysiology of pulmonary vein restenosis is not well understood. Medial fibrosis of the injured pulmonary veins, endothelial ingrowth into the stent, and abnormal reactivity of the pulmonary vascular bed have been proposed as possible mechanisms of restenosis.

Pulmonary Vein Varix

Overview: Pulmonary varices are rare aneurysmal dilations of the pulmonary veins23 and may be congenital or acquired. Acquired pulmonary varices usually are the result of pulmonary venous hypertension, caused by central pulmonary vein stenosis, mitral regurgitation, mitral stenosis, and coarctation. Pulmonary varices generally are benign and require no specific treatment. They usually regress with correction of the underlying abnormality. However, it is important to distinguish pulmonary varices from pulmonary arteriovenous malformations, which can have a similar appearance. Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations carry the risk of stroke and other embolic events and require surgical removal or catheter embolization.

Neoplasms of the Great Vessels

Overview: Primary neoplasms of the great vessels are very rare; fewer than 400 cases have been reported in adults. Most of these malignant tumors are sarcomas. Of primary neoplasms that involve the aorta, fewer than 140 cases have been reported; most are undifferentiated sarcomas, with angiosarcoma being the next most common type of neoplasm.24 These primary tumors have not been described in children. Secondary involvement of the great vessels by invasion or compression from a nearby, nonvascular tumor or by radiation vasculitis from radiation treatment can occur. Examples of secondary tumors include mediastinal lymphoma, germ cell tumor, teratoma, rare types of sarcomas, and mediastinal metastasis.25,26

Imaging and Treatment: Because most great vessel tumors occur as a result of other disease processes, the tumor cell types and origins usually are known (see Chapter 81). The primary roles of imaging are to determine favorable sites for biopsy, evaluate the extent and the degree of vascular obstruction in preparation for vascular intervention, and monitor changes in vascular involvement after treatment. In most cases, CT or MRI is used for these purposes.27 Treatment and imaging follow-up depend on the cell type and tumor staging.

Postoperative Complications

Overview: Pseudoaneurysm and stenosis can develop as complications of surgical repair or interventional treatment of pediatric thoracic great vessels, of which coarctation is the best studied. The average restenosis rates are 15% and 2% for balloon angioplasty and surgical repair of coarctation, respectively (Fig. 83-7).28 Other surgical procedures that can be complicated by aneurysm or stenosis are surgical aortopulmonary and central shunts.29 The Blalock-Taussig shunt, which classically connects the right subclavian artery to the right pulmonary artery, can lead to stenosis or obstruction of the right pulmonary artery (Fig. 83-8). The Potts shunt, which connects the descending aorta to the left pulmonary artery, often results in left pulmonary artery stenosis. The Waterston shunt connects the ascending aorta to the pulmonary trunk. Control of shunt flow is difficult, and excessive flow can create a massive aneurysm of the pulmonary artery (Fig. 83-9). For these reasons, both Potts and Waterston shunts are rarely used today.

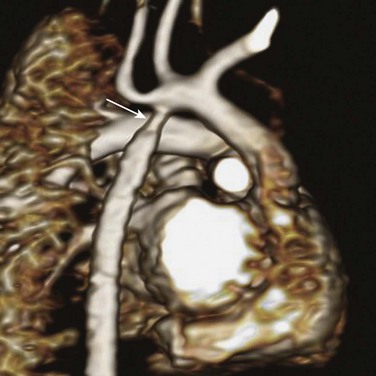

Figure 83-7 Restenosis 5 months after a surgical repair for coarctation in a 6-month-old boy.

Volume rendering shows a segmental, circumferential narrowing (arrow) at the surgical site.

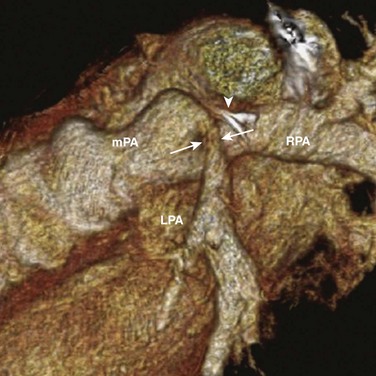

Figure 83-8 Postsurgical pulmonary artery stenosis in a 10-year-old boy.

Volume rendering of a computed tomographic angiogram shows evidence of an arteriopulmonary shunt, now closed, identified by a surgical clip (arrowhead). Adjacent to this clip is a kink and a focal narrowing (arrows) of the left pulmonary artery (LPA). mPA, Main pulmonary artery; RPA, right pulmonary artery.

Imaging and Treatment: Noninvasive imaging by CTA or MRA has largely supplanted catheter angiography for the purpose of detecting and characterizing these thoracic vascular lesions before surgical or interventional treatment. Catheterization is reserved for angioplasty and stenting of stenotic lesions and for stent graft deployment to exclude an aneurysm.

Babyn, PS, Gahunia, HK, Massicotte, P. Pulmonary thromboembolism in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35:258–274.

Bendel, EC, Maleszewski, JJ, Araoz, PA. Imaging sarcomas of the great vessels and heart. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2011;32:377–404.

Lowe, LH, Bulas, DI, Eichelberger, MD, et al. Traumatic aortic injuries in children: radiologic evaluation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:39–42.

Stein, PD, Fowler, SE, Goodman, LR, et al. Multidetector computed tomography for acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2317–2327.

Williams, BJ, Mulvihill, DM, Pettus, BJ, et al. Pediatric superior vena cava syndrome: assessment at low radiation dose 64-slice CT angiography. J Thorac Imaging. 2006;21:71–72.

References

1. Coady, MA, Rizzo, JA, Goldstein, LJ, et al. Natural history, pathogenesis, and etiology of thoracic aortic aneurysms and dissections. Cardiol Clin. 1999;17:615–635.

2. Cox, CS, Jr., Black, CT, Duke, JH, et al. Operative treatment of truncal vascular injuries in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:462–467.

3. Takach, TJ, Anstadt, MP, Moore, HV. Pediatric aortic disruption. Tex Heart Inst J. 2005;32:16–20.

4. Lowe, LH, Bulas, DI, Eichelberger, MD, et al. Traumatic aortic injuries in children: radiologic evaluation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:39–42.

5. Spouge, AR, Burrows, PE, Armstrong, D, et al. Traumatic aortic rupture in the pediatric population: role of plain film, CT and angiography in the diagnosis. Pediatr Radiol. 1991;21:324–328.

6. Karmy-Jones, R, Hoffer, E, Meissner, M, et al. Management of traumatic rupture of the thoracic aorta in pediatric patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:1513–1517.

7. Van Ommen, CH, Peters, M. Acute pulmonary embolism in childhood. Thromb Res. 2006;118:13–25.

8. Monagle, P, Adams, M, Mahoney, M, et al. Outcome of pediatric thromboembolic disease: a report from the Canadian Childhood Thrombophilia Registry. Pediatr Res. 2000;47:763–766.

9. Journeycake, JM, Buchanan, GR. Thrombotic complications of central venous catheters in children. Curr Opin Hematol. 2003;10:369–374.

10. Nuss, R, Hays, T, Chudgar, U, et al. Antiphospholipid antibodies and coagulation regulatory protein abnormalities in children with pulmonary emboli. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1997;19:202–207.

11. Babyn, PS, Gahunia, HK, Massicotte, P. Pulmonary thromboembolism in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2005;35:258–274.

12. Stein, PD, Fowler, SE, Goodman, LR, et al. Multidetector computed tomography for acute pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2317–2327.

13. Goldenberg, NA, Knapp-Clevenger, R, Hays, T, et al. Lemierre’s and Lemierre’s-like syndromes in children: survival and thromboembolic outcomes. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e543–e548.

14. Yellin, A, Mandel, M, Rechavi, G, et al. Superior vena cava syndrome associated with lymphoma. Am J Dis Child. 1992;146:1060–1063.

15. Robertson, BD, Bautista, MA, Russell, TS, et al. Fibrosing mediastinitis secondary to zygomycosis in a twenty-two-month-old child. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21:441–442.

16. Santoro, G, Ballerini, L, Bialkowski, J, et al. Stent implantation for post-Mustard systemic venous obstruction. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1998;14:332–334.

17. Williams, BJ, Mulvihill, DM, Pettus, BJ, et al. Pediatric superior vena cava syndrome: assessment at low radiation dose 64-slice CT angiography. J Thorac Imaging. 2006;21:71–72.

18. Kamath, PS. Budd-Chiari syndrome: radiologic findings. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:S21–S22.

19. Pasic, M, Schopke, W, Vogt, P, et al. Aneurysm of the superior mediastinal veins. J Vasc Surg. 1995;21:505–509.

20. Joseph, AE, Donaldson, JS, Reynolds, M. Neck and thorax venous aneurysm: association with cystic hygroma. Radiology. 1989;170:109–112.

21. Devaney, EJ, Ohye, RG, Bove, EL. Pulmonary vein stenosis following repair of total anomalous pulmonary venous connection. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2006:51–55.

22. Wax, DF, Rocchini, AP. Transcatheter management of venous stenosis. Pediatr Cardiol. 1998;19:59–65.

23. Platzker, J, Goldhammer, E, Simon, J, et al. Pulmonary varices, benign congenital anomalies simulating perihilar masses of various etiologies. Clin Cardiol. 1984;7:295–298.

24. Chiche, L, Mongredien, B, Brocheriou, I, et al. Primary tumors of the thoracoabdominal aorta: surgical treatment of 5 patients and review of the literature. Ann Vasc Surg. 2003;17:354–364.

25. Bagatell, R, Morgan, E, Cosentino, C, et al. Two cases of pediatric neuroblastoma with tumor thrombus in the inferior vena cava. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2002;24:397–400.

26. Upadhyaya, M, Jaffar, SM, Tomas-Smigura, E. Recurrent immature mediastinal teratoma with life-threatening respiratory distress in a neonate. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2003;13:403–406.

27. Bendel, EC, Maleszewski, JJ, Araoz, PA. Imaging sarcomas of the great vessels and heart. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2011;32:377–404.

28. Brown, ML, Burkhart, HM, Connolly, HM, et al. Late outcomes of reintervention on the descending aorta after repair of aortic coarctation. Circulation. 2010;122:S81–S84.

29. Sachweh, J, Dabritz, S, Didilis, V, et al. Pulmonary artery stenosis after systemic-to-pulmonary shunt operations. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1998;14:229–234.