125 Acne

Etiology And Pathogenesis

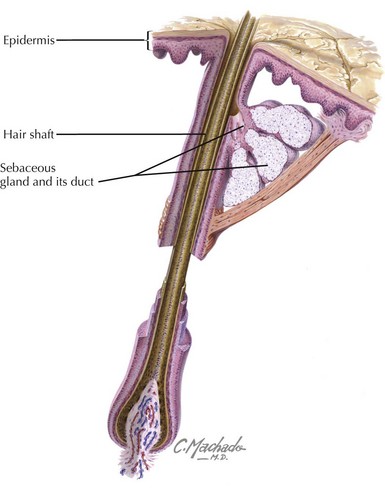

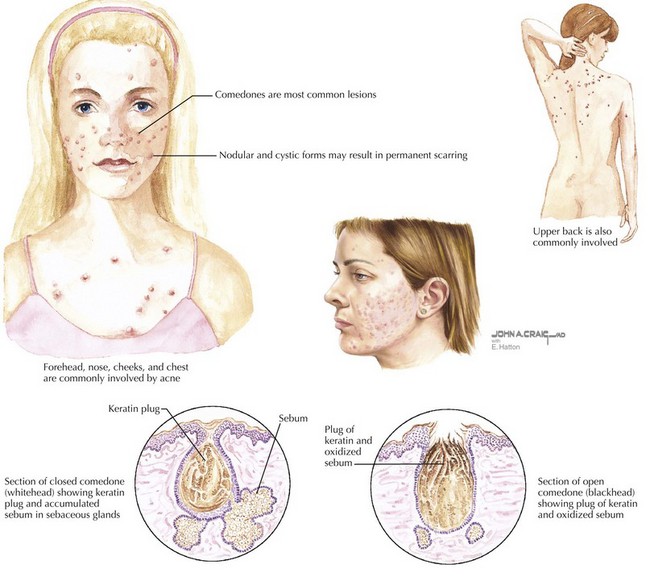

An appreciation of the pathogenesis of acne facilitates a better understanding of targeted treatments. Acne develops in the pilosebaceous unit (Figure 125-1). There are four primary factors involved: abnormal keratinization, increased sebum production, proliferation of Propionibacterium acnes bacteria, and inflammation. With the onset of adrenarche, there is an increase in androgen production and a resultant increase in sebum secretion. Each sebaceous gland has a different threshold of androgen sensitivity, effecting an individually unique response to puberty. Simultaneously, there is increased proliferation of keratinocytes and decreased desquamation. The accumulation of sebum and keratinocytes leads to the formation of the microcomedo, the precursor to acne lesions. P. acnes, a normal skin inhabitant, thrives in this lipid-rich environment. The organisms release chemotactic factors, setting up an inflammatory response. Depending on the contribution of each primary factor, a microcomedo can evolve into a closed comedo (whitehead), open comedo (blackhead) (Figure 125-2), or an inflammatory pustule, papule, or nodule if the sebum, keratin, and microorganisms, with the accumulation of inflammatory cells, rupture into the dermis.

Clinical Presentation

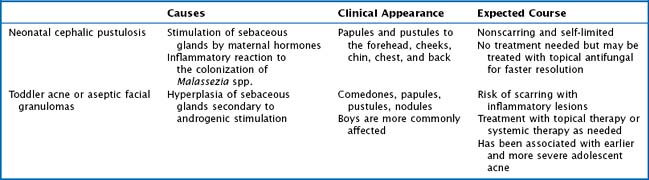

Acne is a disease that can be seen in the first year of life, early childhood, the prepubertal period, and puberty. Neonatal cephalic pustulosis, formerly referred to as neonatal acne, appears in the first 3 months after birth and usually resolves in 1 to 3 months. In neonates, it is extremely important to exclude other bacterial, viral, or fungal causes, but a physician should also consider milia, erythema toxicum neonatorum, transient neonatal pustulosis, and sebaceous gland hyperplasia. Infantile or toddler acne is less common and usually presents between 3 and 6 months of life and can last 1 to 2 years. This is not typically associated with precocious puberty or a hormonal imbalance but needs to be considered in conjunction with a thorough history and physical examination. See Table 125-1 for a comparison of acne seen in neonates and toddlers. Acne can present in any location where there are sebaceous glands. In addition to the face, it is frequently found on the neck, upper chest, shoulders, and back (see Figure 125-2). There are multiple classification systems used to talk about acne, but a description of the lesions and their locations is most helpful. The resolution of acne may leave postinflammatory changes that usually resolve themselves but may take weeks to months, especially in darker pigmented patients. Moderate and severe acne can leave permanent scars.

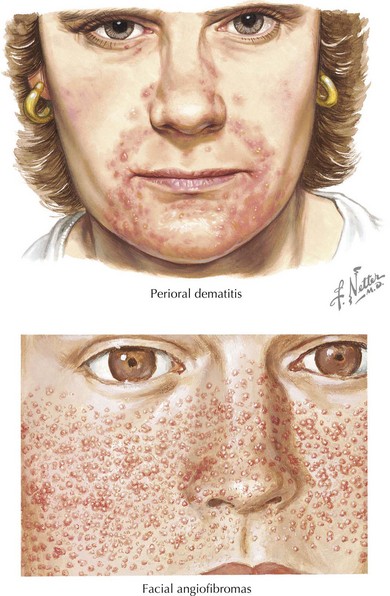

The diagnosis of acne is relatively straightforward. Typical acne includes comedones, papules, pustules, and nodules in the distribution of the face, upper back, and chest. Acne that begins at an abnormal age, particularly severe acne, acne accompanied by an abnormal growth history or virilization, or acne that is recalcitrant to treatment, should be further evaluated. The physician may want to consider an underlying disorder, such as premature adrenarche, precocious puberty, Cushing’s syndrome, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, and gonadal or adrenal tumors, or an alternative diagnosis if the lesions are not typical (Box 125-1). Perioral dermatitis and facial angiofibromas are shown in Figure 125-3.

Management

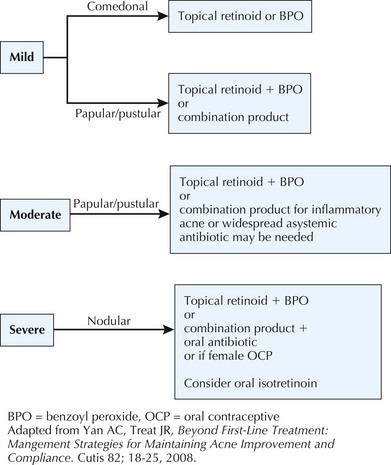

See Figure 125-4 for an acne treatment algorithm for the initial management strategies for the treatment of acne.

Topical Retinoids

Caution should be taken when adding multiple therapies at the same time because they can all be drying. It is generally better to start with a lower strength formulation and increase it as needed. Cream formulations of retinoids are less potent but also less irritating than their gel counterparts. See Table 125-2 for examples of topical retinoids available in the United States.

| Retinoids | Comments | Side Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Tretinoin (available in cream, gel, solution, microsphere gel) | Tretinoin is affected by light and degrades to a greater extent when used together with benzoyl peroxide. | Irritation, erythema, burning, pruritus |

| Adapalene (available in gel or cream) | Well tolerated at its lowest concentration but can be less effective. May be used concomitantly with benzoyl peroxide |

|

| Tazarotene (available in gel or cream) | More irritating but effective at comedolysis. Tazarotene is contraindicated during pregnancy. |

Systemic Antibiotics and Other Systemic Therapies

Oral antibiotics should be used for the treatment of moderate to severe acne or widespread involvement of the trunk. Although maintaining retinoid therapy is important for the prevention of acne, as already mentioned, treatment with oral antibiotics should be discontinued after a taper with the resolution of inflammatory lesions (Table 125-3).

| Medication | Comments | Some Notable Side Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Erythromycin | Useful in younger patients who have contraindications to tetracycline use | GI upset, drug interactions |

| Tetracycline | Avoid in children younger than 8 years of age and pregnant women because of permanent discoloration of the teeth and abnormal skeletal development Should not be taken with calcium-based foods or medications because they will decrease absorption |

GI upset, photosensitivity, tooth discoloration |

| Doxycycline | Phototoxicity, GI upset | |

| Minocycline | Pseudotumor cerebri, vertigo, SLE-like reaction, systemic hypersensitivity and Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and autoimmune hepatitis | |

| Oral contraceptives containing estrogen | Ortho Tri-Cyclen, Estrostep, and Yaz are approved by the FDA for acne | Increased risk of thromboembolism, weight changes, mood changes |

| Spironolactone | Menstrual irregularities | |

| Isotretinoin | Possible correlation with isotretinoin and depression has been made; the FDA has implemented iPLEDGE, a program that monitors all patients who are prescribed isotretinoin | Teratogenicity, hypertriglyceridemia, leukopenia, and elevated liver function test results; more commonly, patients develop dry skin, eyes, and mucosa |

FDA, Food and Drug Administration; GI, gastrointestinal SLE, systemic lupus erythematous.

Thiboutot D, Gollnick H, Bettoli V, et al. New insights into the management of acne: an update from the Global Alliance to Improve Outcomes in Acne group. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(5 suppl):S1-S50.

Yan AC, Treat JR. Beyond first-line treatment: management strategies for maintaining acne improvement and compliance. Cutis. 2008;82(2 suppl 1):18-25.

Zaenglein AL. Expert recommendations for acne management. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1188-1199.