Chapter 661 Acne

Acne Vulgaris

Acne, particularly the comedonal form, occurs in 80% of adolescents.

Pathogenesis

The primary pathogenetic alterations in acne are (1) abnormal keratinization of the follicular epithelium, resulting in impaction of keratinized cells within the follicular lumen; (2) increased sebaceous gland production of sebum; (3) proliferation of Propionibacterium acnes within the follicle; and (4) inflammation. Comedonal acne (Fig. 661-1), particularly of the central face, is frequently the first sign of pubertal maturation. At puberty, the sebaceus gland enlarges and sebum production increases in response to the increased activities of androgens of primarily adrenal origin. Most patients with acne do not have endocrine abnormalities. Hyperresponsiveness of the sebocyte to androgens is likely involved in determining the severity of acne in a given individual. Sebocytes and follicular keratinocytes contain 5α-reductase and 3β- and 17β-hydroxyl-steroid dehydrogenase, which are capable of metabolizing androgens. A significant number of women with acne (25-50%), particularly those with relatively mild papulopustular acne, note that their acne flares about 1 wk before menstruation.

Clinical Manifestations

Acne vulgaris is characterized by 4 basic types of lesions: open and closed comedones, papules, pustules (Fig. 661-2), and nodulocystic lesions (Fig. 661-3 and Table 661-1). One or more types of lesions may predominate. In its mildest form, which is often seen early in adolescence, lesions are limited to comedones on the central area of the face. Lesions may also involve the chest, upper back, and deltoid areas. A predominance of lesions on the forehead, particularly closed comedones, is often attributable to prolonged use of greasy hair preparations (pomade acne) (Fig. 661-4). Marked involvement on the trunk is most often seen in males. Lesions often heal with temporary postinflammatory erythema and hyperpigmentation. Pitted, atrophic, or hypertrophic scars may be interspersed, depending on the severity, depth, and chronicity of the process. Diagnosis of acne is rarely difficult, although flat warts, folliculitis, and other types of acne may be confused with acne vulgaris.

| SEVERITY | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Mild | Comedones (noninflammatory lesions) are the main lesions. Papules and pustules may be present but are small and few in number (generally < 10). |

| Moderate | Moderate numbers of papules and pustules (10-40) and comedones (10-40) are present. Mild disease of the trunk may also be present. |

| Moderately severe | Numerous papules and pustules are present (40-100), usually with many comedones (40-100) and occasional larger, deeper nodular inflamed lesions (up to 5). Widespread affected areas usually involve the face, chest, and back. |

| Severe | Nodulocystic acne and acne conglobata with many large, painful nodular or pustular lesions are present, along with many smaller papules, pustules, and comedones. |

From James WD: Clinical practice: acne, N Engl J Med 352:1463–1472, 2005.

Treatment

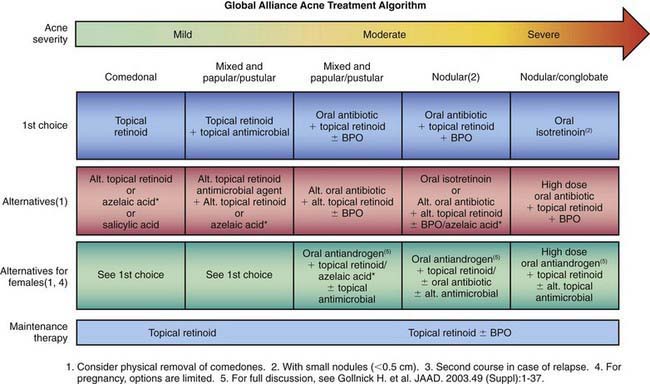

No evidence shows that early treatment, with the exception of isotretinoin, alters the course of acne. Acne can be controlled and severe scarring prevented by judicious maintenance therapy that is continued until the disease process has abated spontaneously. Therapy must be individualized and aimed at preventing microcomedone formation through reduction of follicular hyperkeratosis, sebum production, the P. acnes population in follicular orifices, and free fatty acid production. Initial control takes at least 6-8 wk, depending on the severity of the acne (Table 661-2 and Fig 661-5). It is also important to address the potentially severe emotional impact of acne on adolescents.

Table 661-2 TYPICAL TREATMENT REGIMENS FOR ACNE

COMEDONAL ACNE

MILD PAPULOPUSTULAR ACNE

SEVERE PAPULOPUSTULAR OR NODULAR ACNE

Figure 661-5 Acne treatment algorithm, BPO, benzoyl peroxide.

(From Thiboutot D, Gollnick H; Global Alliance to Improve Acne, et al: New insights into the management of acne: an update from the global alliance to improve outcomes in acne, J Am Acad Dermatol 60:S1–S50, 2009.)

Topical Therapy

Retinoids

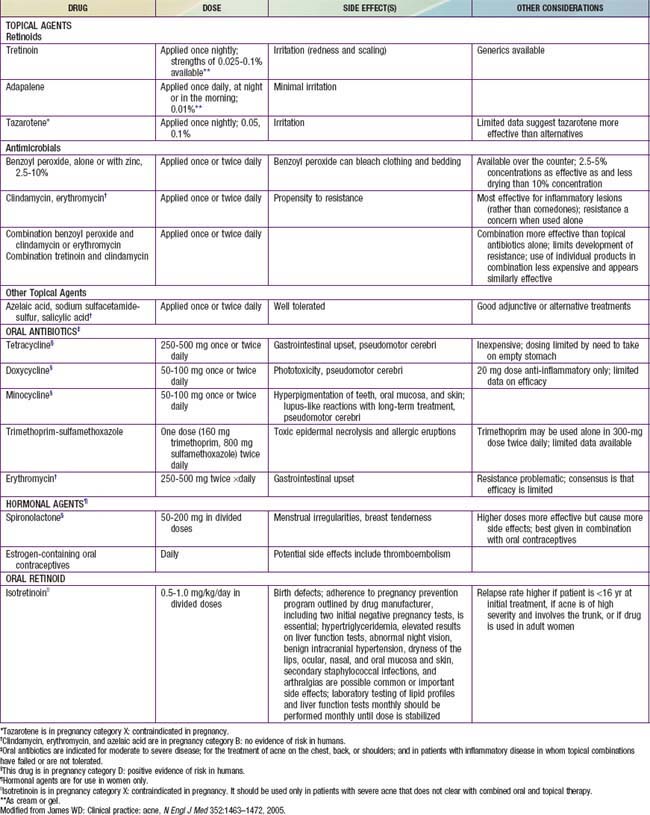

A topical retinoid should be the primary treatment for acne vulgaris. Topical retinoids have multiple actions, including inhibition of the formation and number of microcomedones, reduction of mature comedones, reduction of inflammatory lesions, and production of normal desquamation of the follicular epithelium. Retinoids should be applied daily to all the affected areas. The main side effects of retinoids are irritation and dryness. Not all patients initially tolerate daily use of a retinoid. It is prudent to begin therapy every other or every third day and slowly increase the frequency of application as tolerated. Tretinoin, adapalene, and tazarotene (Table 661-3) are the available retinoids. They are all approximately equal in efficacy, although adapalene is less irritating and tazarotene works slightly better for comedonal acne.

Systemic Therapy

Antibiotics, especially tetracycline and its derivatives (see Table 661-3), are indicated for treatment of patients whose acne has not responded to topical medications, who have moderate to severe inflammatory papulopustular and nodulocystic acne, and who have a propensity for scarring. Tetracycline and its derivatives act by reducing the growth and metabolism of P. acnes. They also have anti-inflammatory properties. For most adolescent patients, therapy may be initiated twice daily, for at least 6-8 wk, followed by a gradual decrease to the minimal effective dose. The drugs should always be administered in combination with a topical retinoid and topical benzoyl peroxide, but not topical antibiotics. Tetracycline absorption is inhibited by food, milk, iron supplements, aluminum hydroxide gel, and calcium-magnesium salts. It should be taken on an empty stomach 1 hr before or 2 hr after meals. Minocycline and doxycycline may be taken with food. Side effects of tetracycline and derivatives are rare. Side effects of tetracycline include vaginal candidosis, particularly in those who take tetracycline concurrently with oral contraceptives; gastrointestinal irritation; phototoxic reactions, including onycholysis and brown discoloration of nails; esophageal ulceration; inhibition of fetal skeletal growth; and staining of growing teeth, precluding its use during pregnancy and in those <8 yr. Doxycycline is the most photosensitizing of the tetracycline derivatives. Rarely, minocycline causes dizziness, intracranial hypertension, bluish discoloration of the skin and mucous membranes, hepatitis, and a lupus-like syndrome. A possible complication of prolonged systemic antibiotic use is proliferation of gram-negative organisms, particularly Enterobacter, Klebsiella, Escherichia coli, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, producing severe, refractory folliculitis.

Isotretinoin use has many side effects. It is highly teratogenic and is absolutely contraindicated in pregnancy. Pregnancy should be avoided for 6 wk after discontinuation of therapy. Two forms of birth control are required, as are monthly pregnancy tests. Concerns over cases of pregnancy despite warnings have prompted a manufacturer registration program, iPLEDGE (www.ipledgeprogram.com), which requires physician enrollment and careful patient pregnancy screening in order to prescribe isotretinoin. Many patients also experience cheilitis, xerosis, periodic epistaxis, and blepharoconjunctivitis. Increased serum triglyceride and cholesterol levels are also common. It is important to rule out pre-existing liver disease and hyperlipidemia before initiating therapy and to recheck laboratory values 4 wk after commencement of therapy. Less common but significant side effects include arthralgias, myalgias, temporary thinning of the hair, paronychia, increased susceptibility to sunburn, formation of pyogenic granulomas, and colonization of the skin with Staphylococcus aureus, leading to impetigo, secondarily infected dermatitis, and scalp folliculitis. Rarely, hyperostotic lesions of the spine develop after more than 1 course of isotretinoin. Concomitant use of tetracycline and isotretinoin is contraindicated because either drug, but particularly when they are used together, can cause benign intracranial hypertension. Although no cause-and-effect relationship has been established, drug-induced mood changes and depression and/or suicide have mandated close attention to psychiatric well-being before and during isotretinoin prescription.

Surgical Therapy

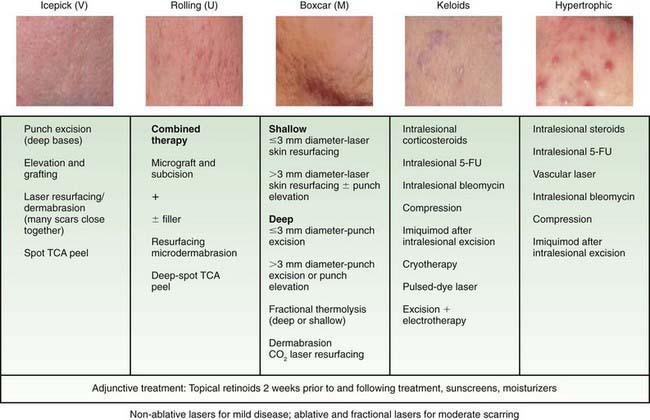

Intralesional injection of low-dose (3-5 mg/mL) mid-potency glucocorticoids (e.g., triamcinolone) with a 30-gauge needle on a tuberculin syringe may hasten the healing of individual, painful nodulocystic lesions. Dermabrasion or laser peel to minimize scarring should be considered only after the active process is quiescent. The management of scarring is described in Figure 661-6.

Figure 661-6 Treatment options for acne scars. CO2, carbon dioxide; FU, fluorouracil; TCA, trichloroacetic acid.

(From Thiboutot D, Gollnick H; Global Alliance to Improve Acne, et al: New insights into the management of acne: an update from the global alliance to improve outcomes in acne, J Am Acad Dermatol 60:S1–S50, 2009.)

Drug-Induced Acne

Pubertal and postpubertal patients who are receiving systemic corticosteroid therapy are predisposed to steroid-induced acne. This monomorphous folliculitis occurs primarily on the face, neck, chest (Fig. 661-7), shoulders, upper back, arms, and rarely on the scalp. Onset follows the initiation of steroid therapy by about 2 wk. The lesions are small, erythematous papules or pustules that may erupt in profusion and are all in the same stage of development. Comedones may occur subsequently, but nodulocystic lesions and scarring are rare. Pruritus is occasional. Although steroid acne is relatively refractory if the medication is continued, the eruption may respond to use of tretinoin and a benzoyl peroxide gel.

Neonatal Acne

Approximately 20% of normal neonates demonstrate at least a few comedones in the first mo of life. Closed comedones predominate on the cheeks and forehead (Fig. 661-8); open comedones and papulopustules occur occasionally. The cause of neonatal acne is unknown but has been attributed to placental transfer of maternal androgens, hyperactive neonatal adrenal glands, and a hypersensitive neonatal end-organ response to androgenic hormones. The hypertrophic sebaceous glands involute spontaneously over a few months, as does the acne. Treatment is usually unnecessary. If desired, the lesions can be treated effectively with topical tretinoin and/or benzoyl peroxide.

Infantile Acne

Infantile acne usually manifests after 1 yr of life, more commonly in boys than girls. Acne lesions are more numerous, pleomorphic, severe, and persistent than in neonatal acne (Fig. 661-9). Open and closed comedones predominate on the face. Papules and pustules occur frequently, but only occasionally do nodulocystic lesions develop. Pitted scarring is seen in 10-15%. The course may be relatively brief, or the lesions may persist for many months, although the eruption generally resolves by age 3 yr. Use of topical benzoyl peroxide gel and tretinoin usually clears the eruption within a few weeks. Oral erythromycin is occasionally necessary. A child with refractory acne warrants a search for an abnormal source of androgens, such as a virilizing tumor or congenital adrenal hyperplasia.

Krakowski AC, Stendardo S, Eichenfield LF. Practical considerations in acne treatment and the clinical impact of topical combination therapy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:S1-S14.

Magin P, Sullivan J. Suicide attempts in people taking isotretinoin for acne. BMJ. 2010;341:c5866.

The Medical Letter. Adapalene-benzoyl peroxide (Epiduo) for acne. Med Lett. 2009;51:31-32.

2010 The Medical Letter. Clindamycin-tretinoin (veltin gel) for acne. Med Lett. 2010;52:102-103.

Purdy S, de Berker D. Acne. BMJ. 2006;333:949-953.

Thiboutot D, Gollnick H, et al. New insights into the management of acne: an update from the global alliance to improve outcomes in acne. Global Alliance to Improve Acne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:S1-S50.

Zaenglein AL, Thiboutot DM. Expert committee recommendations for acne management. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1188-1199.