144 Acetaminophen, Aspirin, and NSAIDs

Acetaminophen

Key Points

Key Points

• Acetaminophen (APAP) is available in numerous formulations, including cold, cough, and pain relief medications.

• ingestion of APAP is the most commonly reported exposure to a potentially toxic pharmacologic agent.

• APAP toxicity is clinically silent up to 24 hours after ingestion. If any abnormalities in vital signs or significant symptoms are present, a coingestant should be suspected.

• A blood specimen for serum APAP determination should be collected 4 hours after ingestion.

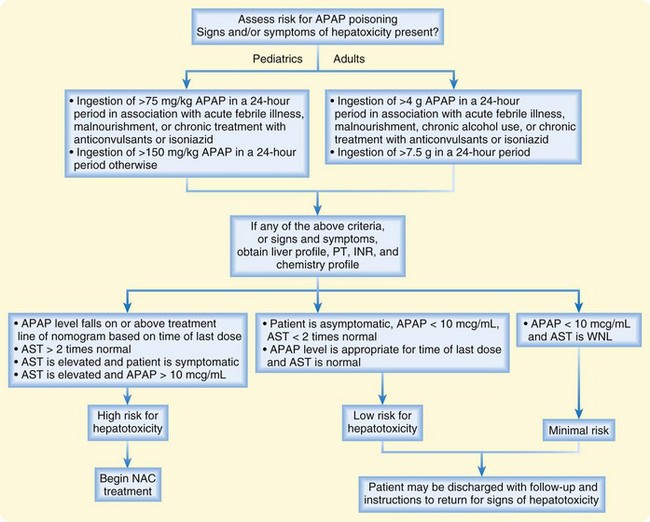

• The serum APAP result should be applied to the APAP nomogram for determination of the patient’s risk for toxicity.

• N-Acetylcysteine (NAC) is the antidote for APAP poisoning, and the approach to treatment depends on the timing of the ingestion and the serum APAP level.

• Oral NAC dosing consists of a loading dose of 140 mg/kg and maintenance dose of 70 mg/kg every 4 hours for 17 doses. An intravenous formulation of NAC is now approved for use and should be given when oral administration is not feasible.

• The serum APAP level should be measured in any patient with clinical suspicion of an overdose or an attempt at suicide or if a patient with an overdose exhibits altered mental status.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Table 144.1 summarizes the four stages of APAP poisoning. The clinical manifestations of an APAP overdose arise from the hepatotoxicity and resultant complications. Patients, even those who eventually progress to fulminant hepatic failure, are initially asymptomatic. Significant abnormalities in vital signs or clinical findings that become evident soon after ingestion should not be attributed to APAP alone; the emergency physician (EP) should pursue diagnosis and treatment of a coingested agent.

| Stage 1 (0-24 hr) | Asymptomatic |

The patient exhibits clinical and laboratory manifestations of hepatic necrosis: varying degrees of hepatic encephalopathy, jaundice, renal failure, coagulation defects, and myocardial abnormalities.

AST and ALT levels peak, the INR value rises, blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels rise, and pH drops.

Death may occur, typically 3-5 days after overdose.

Death from fulminant hepatic failure may be characterized by cerebral edema, sepsis, multisystem organ failure, hemorrhage, and adult respiratory distress syndrome.

ALT, Alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; INR, international normalized ratio.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

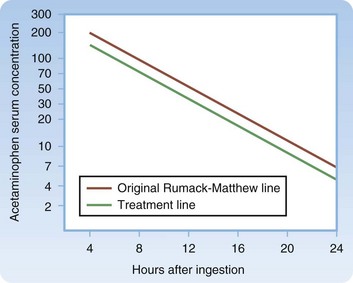

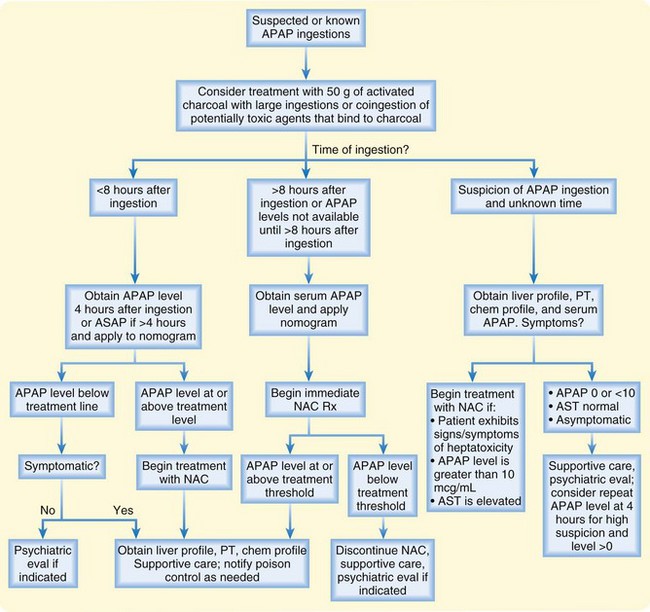

The objective of diagnostic testing after an overdose of APAP is to assist the clinician in determining which patients are at risk for hepatotoxicity and thus require further treatment. Laboratory evaluation is essential for all patients with potential risk because of the lack of reliable clinical manifestations early after APAP ingestion, when antidotal therapy is most effective. Risk is assessed through a thorough history and physical examination, as well as collection of a blood specimen for a serum APAP measurement 4 hours after ingestion—or as soon as possible in patients initially seen more than 4 hours after ingestion—and application of the result to the acetaminophen nomogram (Fig. 144-1). For patients who are seen late after ingestion and already exhibit signs and symptoms of hepatotoxicity or for whom the time of ingestion cannot be readily established, the serum aspartate transaminase (AST) level should also be measured. See Figures 144.2 and 144.3 for guidelines to assess risk after acute and chronic APAP ingestion. Acute ingestion is defined as a single ingestion occurring over a single period shorter than 4 hours.

Fig. 144.1 Treatment nomogram for acute acetaminophen overdose.

(From Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, editors. Rosen’s emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2006.)

Fig. 144.2 Risk assessment and management of acute acetaminophen (APAP) poisoning.

AST, Aspartate aminotransferase; NAC, N-acetylcysteine; PT, prothrombin time.

If there is any clinical suspicion of an overdose, even if the patient does not admit to APAP ingestion or if the patient with an overdose exhibits altered mental status, the serum APAP level should be measured.1 Approximately 1 in 500 patients who have taken an overdose but do not admit to ingestion of APAP have a potentially hepatotoxic serum APAP concentration.

Treatment

Treatment with 50 g of activated charcoal should be considered in patients with large ingestions of APAP or coingestion of APAP and potentially toxic agents that bind to charcoal.2 N-Acetylcysteine (NAC) is the antidote for APAP toxicity.3 If given within 8 hours of ingestion, the risk for significant hepatotoxicity secondary to APAP toxicity is low. There does not appear to be a significant advantage to administering NAC within the first 2 or 3 hours after ingestion over giving it later as long as it is within the 8-hour window. See Figures 144.2 and 144.3 for guidelines in determining which patients should be given NAC after acute and chronic APAP ingestion and in managing patient care. NAC is available in both oral and intravenous formulations.4 In general, both formulations are highly effective and well tolerated. Whether one formulation is superior remains controversial. See Box 144.1 for a comparison of the two formulations and Box 144.2 for dosing regimens.

Box 144.2 Dosing Schedule for N-Acetylcysteine (NAC)

Intravenous

Pediatric (<40 kg)

For patients weighing more than 10 kg, follow the package insert or regimen below

For infants less than 10 kg, dilute IV NAC to a 2% solution and then follow the dosing regimen below: Remove 50 mL from a 500-mL bag of D5W, and add 50 mL IV NAC (20%) to 450 mL D5W to create a 2% solution

Loading dose: 7.5 mL/kg (150 mg/kg) of a 2% solution over a 1-hour period

Second dose: 2.5 mL/kg (50 mg/kg) of a 2% solution over a 4-hour period

Third dose: 5 mL/kg (100 mg/kg) of a 2% solution over a 16-hour period

Patients initially seen longer than 8 hours after ingestion should be treated with NAC on arrival at the emergency department and their serum APAP and AST levels measured. If the APAP level is above the treatment threshold on the nomogram (see Fig. 144.1), treatment with NAC should continue. If not and the patient has no signs or symptoms consistent with hepatotoxicity, NAC should be discontinued. NAC improves morbidity and mortality even if given late after ingestion and even if administered to patients in fulminant hepatic failure after APAP ingestion.5 Rarely, patients with very high APAP levels or those seen late after ingestion may require a prolonged course of NAC. The EP should contact the regional poison control center for further assistance in managing patients with APAP overdose.

Pediatric Considerations

Children should be evaluated for potential risk for hepatotoxicity after both acute exposure and repeated excessive dosing. Serum APAP and AST levels should be measured in those with a large single ingestion or ingestion of more than 75 mg/kg of APAP in a 24-hour period, as well as in any child with signs or symptoms of hepatotoxicity (see Figs. 144.2 and 144.3). NAC should be administered if indicated according to the dosing guidelines (see Box 144.2).

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

Patients deemed to be at risk for hepatotoxicity should be treated with oral NAC within 8 hours of ingestion or as soon as possible thereafter and be admitted to the hospital for further medical and psychiatric evaluation as indicated. Patients with signs of severe hepatotoxicity, hepatic encephalopathy, or fulminant hepatic failure should be admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), and early contact should be made with both the poison control center and a liver transplantation center (Box 144.3).

Aspirin (Salicylates)

Key Points

Key Points

• Methyl salicylate is found in topical liniments and in oil of wintergreen.

• Aspirin toxicity in adults is characterized by a mixed respiratory alkalosis and metabolic acidosis.

• Acute toxicity is marked by tachypnea or hyperpnea, tachycardia, nausea, vomiting, and progressive central nervous system deterioration.

• Chronic aspirin toxicity is seen most commonly in the elderly and is frequently misdiagnosed as sepsis or dementia.6

• Aspirin toxicity is treated with multiple-dose activated charcoal, fluid resuscitation, urine alkalinization, and hemodialysis.

Pathophysiology

Salicylate toxicity in adults is characterized by a mixed respiratory alkalosis and metabolic acidosis. Salicylates stimulate the respiratory center in the brainstem, which causes hyperventilation and a primary respiratory alkalosis. In addition, salicylates cause an anion gap metabolic acidosis, probably through several mechanisms.7 They uncouple oxidative phosphorylation, which leads to an accumulation of hydrogen ions, blocks the production of adenosine triphosphate, and favors the production of lactate. Salicylate toxicity interferes with the renal elimination of sulfuric and phosphoric acids and induces fatty acid metabolism, with the generation of α-hydroxybutyric acid and acetoacetic acid.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

See Box 144.4 for the clinical manifestations of salicylate toxicity and Table 144.2 for comparison of acute and chronic salicylate toxicity.

Box 144.4 Clinical Manifestations of Salicylate Toxicity

Table 144.2 Comparison of Acute and Chronic Salicylate Toxicity

| ACUTE | CHRONIC |

|---|---|

| Seen in toddlers and suicidal adults | Seen primarily in the elderly |

| Typically caused by intentional overdose in suicidal adults or unintentional ingestion by children | Typically caused by unintentional overdose by the elderly for the treatment of chronic pain |

| Acute onset | Insidious onset |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms common | Gastrointestinal symptoms uncommon Central nervous symptoms predominate Typically misdiagnosed as altered mental status |

| Significant toxicity associated with high serum salicylate value | Significant toxicity associated with low to moderately elevated salicylate value |

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

The differential diagnosis for salicylate toxicity includes diabetic ketoacidosis, dementia, withdrawal syndromes, meningitis or encephalitis, acetaminophen overdose, toxic alcohol ingestion, lactic acidosis, and iron toxicity. See Table 144.3 for laboratory and diagnostic tests useful in evaluating salicylate toxicity.

Table 144.3 Diagnostic Testing in Patients with Salicylate Toxicity

| TEST | FINDINGS AND SIGNIFICANCE |

|---|---|

| Serum acetylsalicylic acid measurement |

Treatment

The mainstays of therapy after salicylate ingestion are multiple-dose activated charcoal, fluid and electrolyte replenishment, urine alkalinization, and in cases of severe toxicity, hemodialysis. Table 144.4 lists guidelines for managing and treating patients with salicylate toxicity, instructions on urine alkalization, and indications for hemodialysis. The EP should contact the renal service early in cases of severe toxicity and consult with the regional poison control center for continued assistance soon after patient arrival.

| Gastric decontamination | |

| Fluid replacement |

Need to replenish or maintain serum potassium to achieve urine alkalinization

Monitor serum calcium and replenish as necessary during sodium bicarbonate therapy

Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs

Key Points

Key Points

• Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are a large class of drugs that include the over-the-counter drugs ibuprofen, naproxen, and ketoprofen.

• Nausea, vomiting, epigastric pain, and mild central nervous system depression are the most common clinical manifestations of NSAID poisoning.

• NSAID toxicity is usually mild and should be managed with gastrointestinal decontamination and supportive care.

Pathophysiology

All NSAIDs competitively inhibit cyclooxygenase (COX), thereby preventing the formation of prostaglandins, prostacyclin, and thromboxane.10 (Unlike salicylates, NSAIDs reversibly bind to COX.) There are two isoforms: COX-1 and COX-2. The analgesic and antiinflammatory properties are attributed to inhibition of COX-2. Most of the adverse effects and the acute toxicity of NSAIDs are attributed to inhibition of COX-1.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

See Box 144.5 for the signs and symptoms of NSAID toxicity. Gastrointestinal manifestations are the most common; rare findings after large ibuprofen ingestions include metabolic acidosis, coma, bradycardia, and hypotension.11,12

Treatment

Tips and Tricks

Measure serum acetaminophen in all patients with suspected overdose.

Initiate treatment with N-acetylcysteine in patients seen late after an acetaminophen overdose.

Initiate early contact with the poison control center and liver transplant center for patients with severe acetaminophen toxicity.

Consider chronic salicylate poisoning in elderly patients with altered mental status.

Initiate treatment with sodium bicarbonate and contact the renal service for potential hemodialysis in patients with salicylate poisoning.

Beware of the risk of worsening the acidemia during intubation of patients with severe salicylate poisoning, and ensure adequate ventilation.

1 Lucanie R, Chiang WK, Reilly R. Utility of acetaminophen screening in unsuspected suicidal ingestions. Vet Hum Toxicol. 2002;44:171–173.

2 Renzi FP, Donovan JW, Martin TG, et al. Concomitant use of activated charcoal and N-acetylcysteine. Ann Emerg Med. 1985;14:568–572.

3 Smilkstein MJ, Knapp GL, Kulig KW, et al. Efficiency of oral N-acetylcysteine in the treatment of acetaminophen overdose. Analysis of the National Multicenter Study (1976-85). N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1557–1562.

4 Prescott LF, Illingworth RN, Critchley JA, et al. Intravenous N-acetylcysteine: the treatment of choice for paracetamol poisoning. Br Med J. 1979;2:1097–1100.

5 Harrison PM, Wendon JA, Gimson AE, et al. Improvement by acetylcysteine of hemodynamics and oxygen transport in fulminant hepatic failure. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1852–1857.

6 Anderson RJ, Potts DE, Gabow PA, et al. Unrecognized adult salicylate intoxication. Ann Intern Med. 1976;85:745–748.

7 Gabow PA, Anderson RJ, Potts DE, et al. Acid-base disturbances in the salicylate-intoxicated adult. Arch Intern Med. 1978;138:1481–1484.

8 Barone JA, Raia JJ, Huang YC. Evaluation of the effects of multiple-dose activated charcoal on the absorption of orally administered salicylate in a simulated toxic ingestion model. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17:34–37.

9 Prescott LF, Balali-Mood M, Critchley JA, et al. Diuresis or urinary alkalinisation for salicylate poisoning? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1982;285:1383–1386.

10 Hall AH, Smolinske SC, Stover B, et al. Ibuprofen overdose in adults. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1992;30:23–37.

11 Cryer B, Kimmey MB. Gastrointestinal side effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Med. 1998;105:20S–30S.

12 Clive DM, Stoff JS. Renal syndromes associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:563–572.