Chapter 623 Abnormalities of the Optic Nerve

Optic Nerve Hypoplasia

Optic nerve hypoplasia is a principal feature of septo-optic dysplasia of de Morsier, a developmental disorder characterized by the association of anomalies of the midline structures of the brain with hypoplasia of the optic nerves, optic chiasm, and optic tracts; typically noted are agenesis of the septum pellucidum, partial or complete agenesis of the corpus callosum, and malformation of the fornix, with a large chiasmatic cistern. Patients can have hypothalamic abnormalities and endocrine defects ranging from panhypopituitarism to isolated deficiency of growth hormone, hypothyroidism, or diabetes insipidus. Neonatal hypoglycemia and seizures are important presenting signs in affected infants (Chapter 585).

Optic Nerve Coloboma

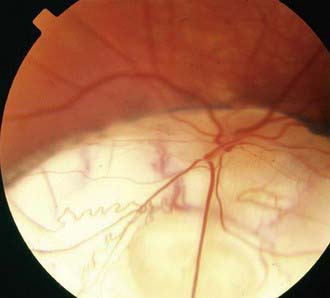

Optic nerve colobomas can be unilateral or bilateral. The visual acuity can range from normal to complete blindness. The coloboma develops secondary to incomplete closure of the embryonic fissure. The defect can produce a partial or total excavation of the optic disc (Fig. 623-1) Chorioretinal and iris colobomas can also occur. Optic nerve colobomas may be seen in a multitude of ocular and systemic abnormalities including the CHARGE association (coloboma, heart disease, atresia choanae, retarded growth and development and/or central nervous system anomalies, genetic anomalies and/or hypogonadism, ear anomalies and/or deafness).

Papilledema

The term papilledema is reserved to describe swelling of the nerve head secondary to increased intracranial pressure (ICP). Clinical manifestations of papilledema include edematous blurring of the disc margins, fullness or elevation of the nerve head, partial or complete obliteration of the disc cup, capillary congestion and hyperemia of the nerve head, generalized engorgement of the veins, loss of spontaneous venous pulsation, nerve fiber layer hemorrhages around the disc, and peripapillary exudates (see Fig. 584-2). In some cases, edema extending into the macula can produce a fan- or star-shaped figure. Concentric peripapillary retinal wrinkling (Paton lines) may be noted. Transient obscuration of vision can occur, lasting seconds and associated with postural changes. Vision, however, is usually normal in acute papilledema. Normally, when the ICP is relieved, the papilledema resolves and the disc returns to a normal or nearly normal appearance within 6-8 wk. Sustained chronic papilledema or long-standing unrelieved increased ICP can, however, lead to permanent nerve fiber damage, atrophic changes of the disc, macular scarring, and impairment of vision.

Optic Neuritis

Optic neuritis can signify one of the many demyelinating diseases of childhood (Chapters 593; 593.2). Although a significant percentage of adults who experience an episode of optic neuritis eventually develop other symptoms associated with multiple sclerosis (MS), young children with optic neuritis are seemingly at less risk (risk of MS is 19% within 20 yr). Bilateral optic neuritis in children may be associated with neuromyelitis optica (Devic disease; Chapter 593.2). This syndrome is characterized by rapid and severe bilateral vision loss accompanied by transverse myelitis and paraplegia. Optic neuritis may also be a complication of long-term high-dose treatment with chloramphenicol or vincristine therapy. Extensive pediatric neurologic and ophthalmic investigation, including MRI and lumbar puncture, is usually required.

Optic Nerve Glioma

Optic nerve glioma (Chapter 491), more properly referred to as juvenile pilocytic astrocytoma, is the most common tumor of the optic nerve in childhood. This neuroglial tumor can develop in the intraorbital, intracanalicular, or intracranial portion of the nerve; the chiasm is often involved.

Auw-Haedrich C, Staubach F, Witschel H. Optic disk drusen. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47:515-532.

Balcer LJ. Optic neuritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1273-1280.

Birkebaek NH, Patel L, Wright NB, et al. Endocrine status in patients with optic nerve hypoplasia: relationship to midline central nervous system abnormalities and appearance of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis on magnetic resonance imaging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5281-5286.

Garcia-Filion P, Fink C, Geffner ME, Borchert M. Optic nerve hypoplasia in North America: a re-appraisal of perinatal risk factors. Acta Ophthalmol. 2010;88:527-534.

Hickman SJ, Dalton CM, Miller DH, et al. Management of acute optic neuritis. Lancet. 2002;360:1953-1962.

Hu K, Davis A, O’Sullivan E. Distinguishing optic disc drusen from papilledema. BMJ. 2009;338:1207-1209.

Lam BL, Feuer WJ, Abukhalil F, et al. Leber hereditary optic neuropathy gene therapy clinical trial recruitment. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(9):1129-1135.

Massaro M, Thorarensen O, Liu GT, et al. Morning glory disc anomaly and moyamoya vessels. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:253-254.

Nicolin G, Parkin P, Mabbott D, et al. Natural history and outcome of optic pathway gliomas in children. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;53:1231-1237.

Optic Neuritis Study Group. Visual function 5 years after optic neuritis. Experience of the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115:1545-1552.

Repka MX, Miller NR. Optic atrophy in children. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;106:191-193.

Skarf B, Hoyt CS. Optic nerve hypoplasia in children: association with anomalies of the endocrine and CNS. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102:62-67.

Weiss AH, Beck RW. Neuroretinitis in childhood. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1989;26:198-203.

of involved eyes. Morning glory disc anomaly has been associated with basal encephalocele in patients with midfacial anomalies. Abnormalities of the carotid circulation can also be seen in patients with morning glory anomaly. Moyamoya disease is a well-described associated finding.

of involved eyes. Morning glory disc anomaly has been associated with basal encephalocele in patients with midfacial anomalies. Abnormalities of the carotid circulation can also be seen in patients with morning glory anomaly. Moyamoya disease is a well-described associated finding. of patients. This recovery can take place years or decades after the initial episode of acute vision loss. The peripapillary angiopathy, the lack of short-term remission, and the degree of symmetry serve to distinguish most cases of Leber disease from the optic neuritis of MS.

of patients. This recovery can take place years or decades after the initial episode of acute vision loss. The peripapillary angiopathy, the lack of short-term remission, and the degree of symmetry serve to distinguish most cases of Leber disease from the optic neuritis of MS.