Abnormalities of the Female Genital Tract

Imaging Techniques

Ultrasound is the key technique used in the analysis of the pediatric gynecologic tract, its diseases, and the simulators of those diseases. Ultrasound provides quick analysis of the uterus, ovaries, and cul-de-sac. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provide a more global view of the pelvis and abdomen than does ultrasound, and they are preferred for the analysis of tumor extent and metastases. The drawbacks of radiation exposure for CT, less control of the patient’s environment for CT and MRI, and sedation needs for MRI are of particular relevance in pediatric patients.1–3

Ovarian and Uterine Development

Overview and Imaging: The two ovaries are ovoid structures generally located posterior or lateral to the uterus within the mesovarium of the broad ligament. Ovaries may be located anywhere along their embryologic course from the inferior border of the kidney to the broad ligament. Ovaries may be involved in indirect inguinal hernias, 15% of which occur in females. Herniated ovaries can extend as low as the labia (e-Fig. 127-1), the female equivalent of the scrotum.1–5

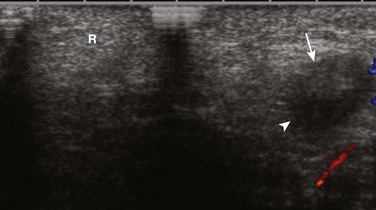

e-Figure 127-1 A herniated left ovary.

A transverse sonogram shows an unremarkable right labia (R). The left labia contained an echopenic mass (arrow) with a contained cystic area (arrowhead) that is somewhat difficult to see on this image. The mass proved to be a herniated labial ovary with a normal contained follicle.

Adnexal volume is determined by ultrasound using the formula for a modified prolate ellipse: (0.523) × L × W × D. Length (L) and depth (D) usually are measured on a longitudinal (parasagittal) image, and width (W) is measured on a transverse view (Fig. 127-2). In the first 3 months of life, when gonadotropin levels are highest in children, ovarian volumes average 1.06 cm3 but have a range of normal as high as 3.6 cm3. The high end of the range of normal is 2.7 cm3 for 4- to 12-month-olds and 1.7 cm3 for 13- to 24-month-olds. The mean ovarian volume reported for children older than 2 years who have not undergone puberty is 1 cm3. For menstruating females, the mean ovarian volume typically is 6 to 9.8 cm3.1,6–10

Ultrasound routinely identifies follicles or cysts in most children of all ages. Cysts were noted in 80% of the imaged ovaries of a group of healthy children who were newborn to 2 years old, 72% of a 2- to 6-year-old group, and 68% of a 7- to 10-year-old group (Fig. 127-3). Macrocysts occasionally are seen in all age groups. The ovary is not a quiescent organ in childhood but rather is a dynamic organ undergoing constant internal change.1,11

The Normal Uterus

Overview and Imaging: The uterus of the newborn has a mean length of 3.5 cm, which decreases to 2.6 to 3 cm by the fourth month of life as gonadotropin levels decrease. On ultrasound examination of a newborn’s uterus, it is not uncommon to find either a hypoechoic halo around an echogenic endometrial cavity stripe or endometrial cavity fluid.1,3,12 The typical newborn’s uterus is shaped like a spade, with the anteroposterior diameter of the cervix as much as twice that of its fundus (Fig. 127-4). The newborn’s cervix is also longer than the fundus. After the first year of life, the typical uterus is tube shaped and remains that way for several years (e-Fig. 127-5).1,3,13

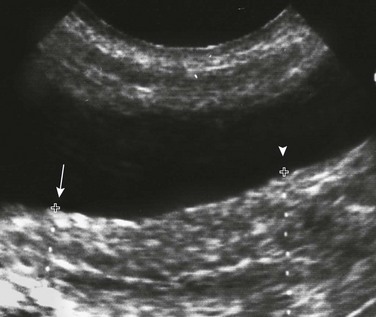

Figure 127-4 A normal neonatal uterus.

A longitudinal sonogram shows a spade-shaped uterus posterior to the bladder. Cursors (arrow) show a relatively narrow uterine fundus compared with the far wider cervical region (arrowhead) of the newborn’s uterus. Note the central echogenic line, which is the endometrial cavity. (From Cohen HL. The female pelvis. In: Siebert J, ed. Syllabus: current concepts: a categorical course in pediatric radiology. Chicago: RSNA Publications; 1994.)

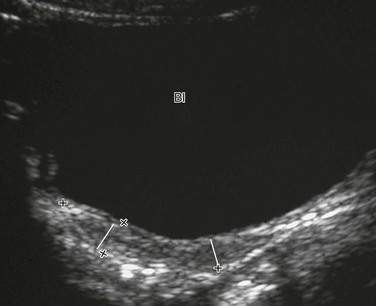

e-Figure 127-5 A normal prepubertal uterus.

A longitudinal sonogram of a 6-year-old child. Lines mark off the widths of the cervical area and fundal area, which are similar. Bl, Bladder.

Uterine length increases gradually between 3 and 8 years of age. The mean perimenarchal measurement is 4.3 cm. After puberty, the typical pear-shaped (Fig. 127-6) uterus measures 5 to 8 cm in length. It is said to descend deeper in the pelvis and no longer maintains the typical neutral position of premenarchal life but instead may be anteverted or retroverted.1,14

Nonneoplastic Disorders of the Female Pelvis

Overview: The müllerian duct system (MDS) develops into the fallopian tubes, uterus, and upper two thirds of the vagina, and the wolffian system degenerates. External genital development proceeds along female lines except in the presence of androgens. By 11 weeks, a Y-shaped uterovaginal primordium has developed into the two fallopian tubes and, with fusion of a large portion of the MDS of both sides, a single uterus and upper two thirds of the vagina. Nonfusion or variably incomplete fusion of the MDS can lead to a wide spectrum of anomalies (Fig. 127-7). The association of uterine and renal abnormalities is quite common, and when a gynecologic anomaly is present, one should evaluate for renal anomalies or agenesis (e-Fig. 127-8) and vice versa.1,15

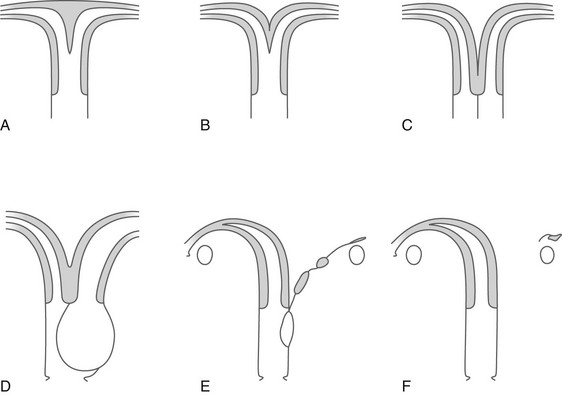

Figure 127-7 Fusion defects of the müllerian ducts (septate vagina with normal uterus not included).

A, Uterus subseptus (uterus septus if the septum extends to the cervix). B, Uterus bicornis unicollis. C, Uterus duplex bicornis bicollis and uterus didelphys with a septate vagina. D, Uterus didelphys with congenital occlusion of one hemivagina. E and F, A rudimentary hemiuterus and unicornuate uterus.

Transverse Vaginal Septum and Imperforate Hymen

Overview: In a person with a transverse vaginal septum, the vagina is obliterated by fibrous connective tissue with vascular and muscular elements lined by squamous epithelium. The area of obliteration may be a thin membrane, but more commonly it involves a segment of the vagina (segmental vaginal atresia). The imperforate hymen is a thin membrane, which forms at the junction of the caudal end of the MDS and the cranial end of the urogenital sinus. Both a transverse vaginal septum and imperforate hymen may present with an obstructed uterus and vagina.1,12,16–19

A distended vagina (colpos) or uterus (metros) is filled with secretions (muco), fluid (hydro), or blood (hemato). For example, hematometrocolpos is defined as hemorrhagic material filling a distended vagina and uterus. It is suggested on physical examination by either seeing an interlabial mass or palpating a pelvic mass. Clinical presentation in the teenage years includes amenorrhea (despite normal development of secondary sex characteristics) and cyclic crampy abdominal pains, or a pelvic mass resulting from accumulation of menstrual blood in the proximal vagina (and uterus and tubes). Complete or partial obstructions may occur in association with various MDS anomalies.1,15,20–22

Imaging: Ultrasound images are similar in appearance whether seen in a neonate or a menarchal teenager. The distended vagina appears as a tubular mass that usually is midline, often with contained echogenicities either from accumulated cervical mucus secretions or hemorrhage from sloughing of a hormonally stimulated endometrial lining. The uterus can be identified separately from the vagina by the thick muscular uterine wall, whereas the vaginal wall is thin (Fig. 127-9). Pelvic MRI in the sagittal or coronal plane can show the dilated vagina as well (Fig. 127-10).1,15,16,23,24

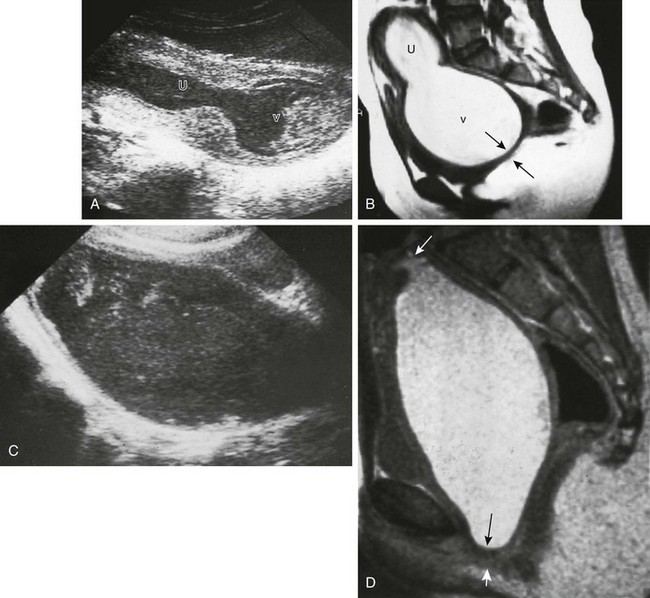

Figure 127-9 Hematometrocolpos.

A longitudinal sonogram in this patient with pelvic pain and amenorrhea shows a dilated vagina (V). It contains debris with a fluid-debris level (arrowheads) anteriorly. The uterus (U) has a smaller amount of contained fluid (arrow). The uterus can be distinguished from the vagina by its thick muscular wall. The cause in this patient was an imperforate hymen. (From Cohen H, Haller J. Pediatric and adolescent genital abnormalities. Clin Diagn Ultrasound. 1988;24:187-216.)

Figure 127-10 Hematometrocolpos from an imperforate hymen.

A, A longitudinal sonogram shows a large midline cystic structure consistent with a distended vagina (v) and uterus (U). The lower part of the vagina contains echogenic material. The patient is a 13-year-old girl who was evaluated because of crampy abdominal pain and a pelvic mass. The external genitalia appeared normal on inspection. B, A midline sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance image (MRI) obtained for presurgical planning shows an enlarged vagina (v) and uterus (U) filled with material consistent with old blood. The obstruction is in the distal vagina and measures 0.5 cm in thickness (arrows). At surgery, this was either a very low vaginal septum or a very thick imperforate hymen. C and D, Hematocolpos from vaginal atresia in a 12-year-old girl who underwent examination because of crampy abdominal pain and a pelvic mass. C, A longitudinal sonogram shows a large midline cystic structure containing debris consistent with hematocolpos. D, A midsagittal T2-weighted MRI shows a markedly distended vagina filled with material consistent with old blood. The uterus (top arrow) is not enlarged. The occlusion is in the distal segment of the vagina and measures more than 0.5 cm in thickness (bottom arrows). At surgery, the obstruction was found to be a thick vaginal septum or a short zone of vaginal atresia.

Treatment: The vaginal obstruction in patients with congenital hydrocolpos is corrected in the newborn period. In patients presenting with hematometrocolpos at puberty, the obstruction should be corrected as promptly as possible to avoid endometriosis as a result of distal obstruction and repeated reverse spillage of menstrual blood into the peritoneal cavity through the fallopian tubes. Hysterectomy is indicated in patients with vaginal agenesis with a rudimentary uterus and a functional endometrium and in patients with cervical atresia occurring as an isolated lesion or in association with vaginal agenesis (Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome).1,3,22–25

Interlabial Masses in Young Girls

Overview and Imaging: The differential diagnosis of interlabial masses is usually made on visual inspection based on the location and external appearance of the mass. Masses associated with the urethral orifice include prolapse of an ectopic ureterocele—identified as a small, reddened, doughnutlike mass with its central opening being the urethral meatus itself—and cystic dilatation of an obstructed paraurethral (Skene) gland, presenting as a mass located on either side of a displaced urethral meatus. Masses associated with the vaginal introitus include prolapse of a vaginal cyst; a remnant of the wolffian or müllerian duct systems or epithelial inclusions originating from elements of the urogenital sinus; an imperforate hymen (e-Fig. 127-11); cystic dilatation of an obstructed Bartholin gland; and prolapse of a sarcoma botryoides or rhabdomyosarcoma of the vagina.1,3,7

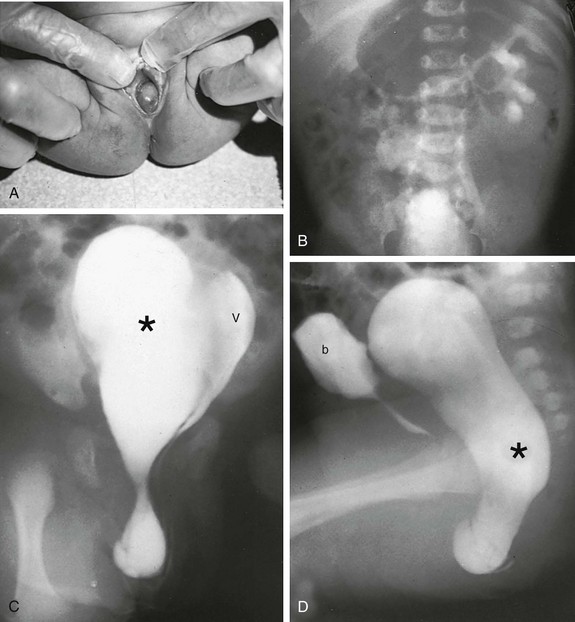

e-Figure 127-11 An occluded right hemivagina.

A, A 2-day-old girl presented with a gray cystic mass at the vaginal introitus. B, Intravenous urography shows no right renal function (probably because of an absent kidney). In a cystogram (not shown), the bladder was displaced forward by the mass. The patent left hemivagina could be catheterized and was found to be displaced to the left. On frontal (C) and lateral (D) vaginograms, contrast material introduced through a needle inserted in the cystic mass at the introitus opacifies a markedly distended right hemivagina and uterus (unilateral hydrometrocolpos) (asterisks). Contrast material from previous studies is still present in the patent vagina (V) and bladder (b).

A cystogram or vaginogram, as well as ultrasound of the bladder and upper genitourinary tract, may be necessary to further define the lesion. CT or MRI may help if continued anatomic questions remain. At times, only surgery is conclusive.1,7,22

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

Overview: Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) is the most serious complication of sexually transmitted diseases. PID includes a spectrum of abnormality that ranges from isolated endometritis to extension of infection into the tubes (salpingitis) and ovaries (oophoritis), potentially resulting in a tuboovarian abscess (TOA), and even extension into the peritoneum as disseminated peritonitis. Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis are the most common etiologic agents.1,26,27

Clinical presentation includes lower abdominal/pelvic pain, purulent vaginal discharge, fever, leukocytosis, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Adnexal tenderness, generally bilateral, and cervical motion tenderness are hallmarks for the clinical diagnosis on bimanual examination.1,26,27

Imaging and Treatment: Early in the course of PID or salpingitis, no abnormal ultrasound findings may be present, and the diagnosis will be based solely on clinical and laboratory evaluation. A helpful ultrasound finding in cases of salpingo-oophoritis is prominent ovaries that may be adherent to the uterus (e-Fig. 127-12). More advanced cases of acute or, more often, chronic PID may demonstrate evidence of hydrosalpinx, pyosalpinx, or TOA. The affected tubal walls may be thickened with intraluminal linear echoes. The echogenicity of the fluid within the fallopian tube is not a reliable indicator of the presence or absence of infection (Fig. 127-13). TOA appears on ultrasound as partial or complete replacement of the normal ovarian tissue by a heterogeneous mass or an echopenic region with contained debris (Fig. 127-14). The contents (debris filled) of the echopenic areas of a TOA often can be better seen by transvaginal ultrasound examination. TOA usually is treated aggressively with intravenous antibiotic regimens and, if necessary, percutaneous drainage or surgery.1,27,28

Figure 127-13 Pyosalpinx.

A midline longitudinal sonogram shows a fluid-filled tubular structure (P), allowing good through-transmission of sound, located posterior to the uterus (cursors). It contains debris and was determined to be a pyosalpinx. B, Bladder.

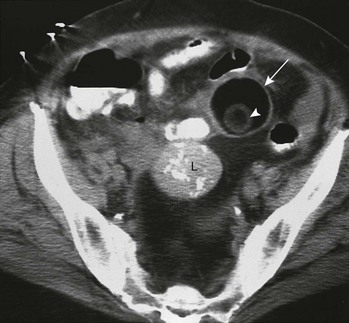

Figure 127-14 A tuboovarian abscess in a teenager with a history of pelvic inflammatory disease.

An oblique transverse sonogram of the right adnexa shows a large, heterogeneous, oval structure with contained echoless circular and tubular structures that were not typical of normal follicles or cysts on transverse or longitudinal images. At times a dilated fallopian tube arising from a tuboovarian abscess accounts for part of the contained cystic structure. This scenario is most likely when the structure appears tubular in at least one of the imaged planes.

e-Figure 127-12 Salpingo-oophoritis.

A transverse sonogram shows prominent adnexa (arrows) hugging the uterus (U), suggesting they are adherent to the uterus. A triangular echogenic area within the uterus was consistent with a prominent endometrial echo, which may be related to menstrual cycle stage or pelvic inflammatory disease.

Ovarian Torsion

Overview: Ovarian torsion is caused by partial or complete rotation of the ovary on its pedicle, compromising first lymphatic, then venous, and finally arterial flow, and leading to hemorrhagic infarction. Torsion of the ovary is most often seen in peripubertal or older girls. Ovarian torsion occurs either in anatomically normal ovaries or in ovaries with an associated ovarian or paraovarian mass or neoplasm.1,29,30

Classic ovarian torsion pain is sudden and acute. Associated complaints of nausea, vomiting, or constipation may occur and mislead the clinician. Fever is rare. Leukocytosis with a left shift may be present. At least half of patients with ovarian torsion claim prior bouts of such pain, suggesting previous torsion and detorsion.1,29,30

Imaging: Ovaries involved in torsion have a variable appearance related to the degree of internal hemorrhage, stromal edema, and infarction that has occurred by the time they are imaged. The ovaries may appear cystic, cystic with septations, cystic with a debris layer, complex with mixed solid and cystic components, or solid. One relatively specific ultrasound image is a unilaterally enlarged solid ovary with multiple peripheral (cortical zone) follicles (Fig. 127-15).1,31

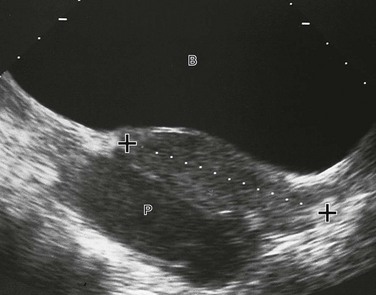

Figure 127-15 Ovarian torsion.

A longitudinal sonogram shows a tubular uterus (U; cursors) that is posterior to the bladder (B) and anterior to a large solid mass with a few peripheral cysts (arrowheads). This image is a relatively classic image of early torsion. Infarction or acute hemorrhage would make the internal contents of the ovary that is undergoing torsion more heterogeneous. (From Cohen HL, Safriel YI. Ovarian torsion. In: Cohen HL, Sivit C, eds. Fetal and pediatric ultrasound: A casebook approach. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001:516.)

An acute ovary that has sustained torsion is larger than a normal ovary. Reported volumes range from only 3.2 to 24 times normal, to ovarian volumes of 150 cm3 or greater in postmenarchal patients. Comparison with the volume and morphology of the contralateral ovary may help make the diagnosis under the appropriate clinical circumstances.1,30,31

Color Doppler imaging in the analysis of cases of ovarian torsion is confusing with regard to its reliability. Well-documented cases exist of surgically proven ovaries that had undergone torsion for which color Doppler imaging showed peripheral and even central arterial flow. Other investigators have reported that an assurance of viability can only be made by imaging central venous flow in an ovary that has undergone torsion. An 87% diagnostic accuracy for determining viability is reported by verifying blood flow changes at the twisted vascular pedicle itself. Patients with no blood flow at the twisted pedicle had necrotic ovaries.1,32–34

Treatment: It is hoped that detorsion and, if necessary, removal of a mass causing torsion will save the gonad and preserve its function. The time from clinical complaint to diagnosis and therapy plays a large role in preserving ovarian function. Doppler imaging may have a role in assessing the recovery of an ovary that has undergone torsion in follow-up studies after surgical treatment.1,35,36

Ovarian Masses

Overview and Imaging: Nonneoplastic cysts of follicular origin (i.e., functional ovarian cysts) are the most common cause of ovarian enlargement. Beyond puberty, the adolescent ovary is similar to that of the adult, developing several follicles early in the menstrual cycle until a dominant follicle develops and ruptures at midcycle, while the others atrophy and resorb. Occasionally one or more of these follicles fails to resorb and instead enlarges as a functional cyst or as a retention cyst. These cysts can reach a large size but usually are no larger than 3 cm. The classic cyst on ultrasound examination is echoless with a sharp back wall and excellent through-transmission. Most functional ovarian cysts are treated conservatively and resolve spontaneously. A 6-week follow-up evaluation allows analysis of the possible ovarian cyst in the other half of a different menstrual cycle, thus documenting resolution or diminution and thereby helping to prove that it is a physiologic cyst and helping to disprove the far less likely diagnosis of a cystic neoplasm.1,37–40

Overview: Functional cysts may develop internal hemorrhage, which occurs when theca interna vessels rupture into the cyst cavity. Such hemorrhagic ovarian cysts can arise from ovarian follicles at any stage in their maturation, even as they involute. The typical clinical presentation of a hemorrhagic ovarian cyst is either sudden, severe, transient lower abdominal pain of 1 to 3 hours’ duration or lower abdominal pain and a palpable mass. The pain is thought to result from sudden distention of the ovarian cyst by the hemorrhage.1,41

Imaging: Most hemorrhagic ovarian cysts are heterogeneous in echogenicity. They may be hypoechoic or hyperechoic areas separated by thin or thick linear echoes of various orientations (Fig. 127-16), echoless with a contained focal echogenicity of variable size clot, contain fluid-debris levels, or appear as a solid mass when clot fills the hemorrhagic ovarian cyst. A changing ultrasound appearance over time can help confirm the diagnosis as fibrin deposition from acute hemorrhaging dissolves and the clot lyses.1,38,41

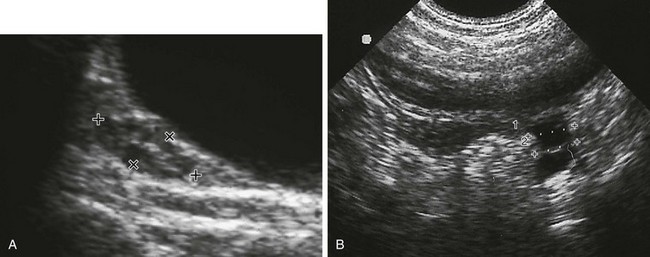

Figure 127-16 A hemorrhagic ovarian cyst.

A longitudinal sonogram shows an echopenic mass (cursors) containing criss-crossing linear echogenicities in the adnexal area of a 12-year-old with acute abdominal pain. A tuboovarian abscess and endometrioma may look similar but present with different clinical scenarios. B, Bladder; U, uterus.

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

Overview: Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS; also known as Stein-Leventhal syndrome) is a hyperandrogenic state with resultant peripheral conversion of larger than normal amounts of estrogen. The chronic hyperestrogenic, hyperandrogenic stimulation leads to chronic anovulation and is responsible for the classic bilaterally enlarged ovaries, which may be asymmetric but usually contain multiple small follicles/cysts. PCOS is the most common pathologic cause of amenorrhea, usually secondary, in adolescents and young adults. Patients often, but far from always, experience the classic triad of obesity (31%), hirsutism (62%), and menstrual abnormalities (80%), including amenorrhea, irregular menses, and prolonged uterine bleeding. Laboratory diagnosis is made by noting increased luteinizing hormone:follicle-stimulating hormone ratios and elevated androstenedione levels.1,42

Imaging: A helpful indicator of PCOS is increased ovarian echogenicity, which is thought to be due to ovarian stromal hypertrophy, which is considered to be evidence of hyperandrogenism. Persons with PCOS have high numbers of subcapsular follicles in their ovaries (Fig. 127-17). Typically, at least five cysts of 5 to 8 mm in diameter are noted on transabdominal ultrasound evaluation of each ovary. Follicles of classic cases should not be larger than 10 mm in diameter. Larger follicles or the presence of a single large (dominant) cyst makes the diagnosis of PCOS unlikely. Ovarian volumes may or may not be greater than the mean for their control group.1,43–46

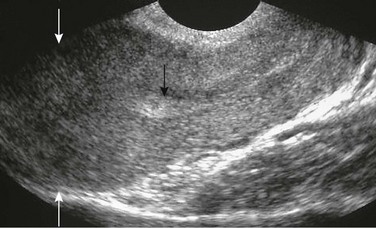

Figure 127-17 Polycystic ovarian disease.

A, A transverse sonogram shows an enlarged left ovary (arrow) containing multiple small follicles is seen adjacent to the uterus (U). A similar right ovary was seen in another plane. The echogenicity of the ovarian stroma is increased. B, A transvaginal sagittal sonogram shows many small follicles (arrowheads) seen within the ovary of a teen with polycystic ovary syndrome. Some bright echogenicity (arrow), which is not seen in normal ovaries, is noted in the superior third of this imaged ovary. C, A sagittal T2-weighted magnetic resonance image shows multiple cortical cysts, particularly at the periphery of the right ovary of a teenager proved to have polycystic ovary syndrome. The ovary is superior to the bladder (B), and its follicles/cysts (arrows) have similar high signal intensity. (A and B from Cohen HL, Ruggiero-Delliturri M. Polycystic ovary syndrome. In: Cohen HL, Sivit C, eds. Fetal and pediatric ultrasound: A casebook approach. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001:496. C courtesy Mark Flyer, MD.)

Neoplasms of the Gynecologic Tract

Overview and Imaging: Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma is the most common genital neoplasm in children of both sexes. It generally is seen before the age of 3 years but rarely at birth. It is rare in older patients. Urogenital sinus remnants are thought to be the origin of some rhabdomyosarcomas, usually originating from the anterior vagina near the cervix. Occasionally they may arise from the cervix. The mass may protrude from the vaginal introitus, often with a polypoid or cluster-of-grapes appearance (botryoid variant). These rhabdomyosarcomas are aggressive tumors that spread rapidly by direct invasion of the vaginal wall and pelvic structures. The tumor may extend to the uterus, bladder, ureters, or rectum. Metastases to regional lymph nodes, the lungs, and other organs may occur. Local recurrence is common.1,47–49

Endodermal sinus tumor of the vagina, also known as yolk sac carcinoma or adenocarcinoma of the infant vagina, usually is seen in infants between 8 and 15 months and rarely after the second year. It often originates in the posterior wall of the vagina (e-Fig. 127-18) and may have a polypoid appearance very similar to that of sarcoma botryoides. The tumor spreads to pelvic soft tissues, paraaortic nodes, liver, and lungs.1,47,49

e-Figure 127-18 An endodermal sinus tumor of the vagina.

A lateral vaginogram shows a mass (arrow) within the contrast-filled vagina of a 6-month-old girl, originating from the vagina’s posterior wall. The contrast-filled bladder seen anterior to the vagina was filled by a separate injection.

Clear cell (or mesonephric) adenocarcinoma usually originates from the vagina and uncommonly from the cervix. It usually is seen after menarche. In the past few decades, about two thirds of patients with this tumor had a history of maternal exposure to diethylstilbestrol or related substances during the first 3 months of pregnancy. These tumors can become quite large, filling the entire vagina by the time of diagnosis. Tumor spread is via the lymphatics and to pelvic nodes. Local recurrence is common. Pulmonary metastases can occur.1,47,49

Ovary

Overview: Ovarian neoplasms commonly are divided into groups based on the apparent origin of their cellular components: germ cell tumors, sex cord/stromal tumors, and surface epithelial tumors. Sixty percent of all pediatric ovarian neoplasms are of germ cell origin. Of the germ cell tumors, 70% are teratomas, 25% are dysgerminomas, and 5% are endodermal sinus or yolk sac tumors. Only one fifth of pediatric ovarian tumors are epithelial cell in origin, including cystadenoma (80%) and cystadenocarcinoma (10%). The final 10% of pediatric ovarian tumors are sex cord tumors or tumors of stromal/mesenchymal origin. Fifteen percent of those are arrhenoblastomas and 75% are granulosa/theca cell tumors.1,47,48

Overall, one third of ovarian neoplasms are malignant. This percentage decreases with increasing age. Half of hormonally active tumors are malignant. Of the malignant lesions, 85% are germ cell tumors (dysgerminomas, immature teratomas, endodermal sinus tumors, embryonal cell carcinomas, and choriocarcinomas); 10% are stromal (Sertoli–Leydig cell, granulosa/theca cell, and undifferentiated neoplasms); and 5% are epithelial cell tumors (serous and mucinous adenocarcinomas). Malignant neoplasms tend to break through the ovary’s capsule and invade adjacent organs. Metastases are most often to the peritoneum, opposite ovary, pelvic and retroperitoneal lymph nodes, omentum, liver, and abdominal organs (e-Fig. 127-19). Involvement of peritoneal and pleural linings may lead to ascites or pleural effusions (Box 127-1).1,47,50

e-Figure 127-19 An endodermal sinus tumor with omental “caking” and peritoneal implants.

A contrast-enhanced computed tomography image shows malignant omental spread (arrowheads) in this 13-year-old with a malignant endodermal sinus tumor of the ovary. Moderate ascites (A) is present. An arrow points to a posterior left-sided peritoneal metastasis. T, The most superior portion of the ovarian tumor. (From Cohen HL, Bober S, Bow S. Imaging the pediatric pelvis: the normal and abnormal genital tract and simulators of its diseases. Urol Radiol. 1992;14:273-283.)

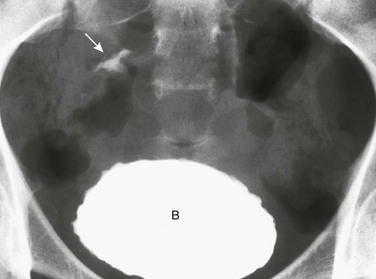

Overview: Mature ovarian teratomas (or dermoid cysts) are the most common ovarian neoplasm in pediatric patients and usually are found in adolescents. The tumors may vary in size from those contained solely within the ovary itself to those that extend 5 to 10 cm beyond the ovary. Almost all dermoids and teratomas are benign, with malignancy found in 2% to 10% of cases or less. Teratomas usually are discovered by chance during pelvic ultrasound examinations performed on adolescents for other reasons; one fourth are bilateral. Occasionally they may be diagnosed by the incidental discovery of calcifications (particularly teeth or bone) in the adnexal area on plain radiograph examination (e-Fig. 127-20).1,50,51

Imaging: Two thirds of teratomas are sonographically complex cysts with anechoic, hypoechoic, and echogenic components. One third of cases are claimed to be either purely echoless (perhaps because the solid component is at the mass’s periphery and not imaged) or purely echogenic. The classic ultrasound appearance shows a prominent cystic component and at least one contained mural nodule (a dermoid plug or Rokitansky projection) (Fig. 127-21) that often is echogenic, with posterior shadowing as a result of contained fat, hair, sebum, or calcium (e.g., tooth or bone). The shadowing may obscure deeper portions of the mass, a phenomenon called the “tip of the iceberg” sign. The anechoic component of teratomas is made up of serous fluid or sebum, which is in a fluid state when at body temperature. Fat–fluid levels and hair–fluid levels may be seen as part of the cystic component. Similar findings are seen on CT (Fig. 127-22) or MRI. CT may show calcifications that are not seen by other methods. MRI is particularly valuable in demonstrating the fatty components of the mass. Signal characteristics on MRI reflect the composition of a teratoma. Calcium, bone, and hair have low signal intensity on both T1- and T2-weighted images. Fat has a high signal on T1-weighted studies. Fluid has a high signal on T2-weighted studies. Immature, partially differentiated malignant teratomas are uncommon and generally are solid and almost universally unilateral.1,48,50–53

Figure 127-21 An ovarian teratoma.

A transverse sonogram shows a large left adnexal mass (arrows) with a highly echogenic component (F). Shadowing that is present (asterisk) distal to the central portion represents a dermoid plug. The echogenicity is predominantly due to fat. Some calcification, which is not evident in this plane, was responsible for the shadowing. The periphery of the mass is fluid with contained debris. (From Ruggierro M, Awobuluyi M, Cohen H, et al. Imaging the pediatric pelvis: role of ultrasound. Radiologist. 1997;4:155-170.)

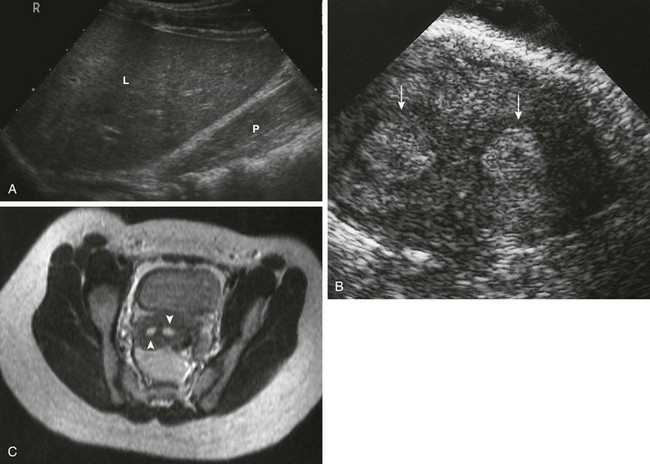

Figure 127-22 Ovarian teratoma.

A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) image shows a circular low Hounsfield unit mass (arrow) in the anterior left pelvis. The CT technique used makes its predominant component appear to be of the same low density as the air seen within nearby bowel or the fat seen in the posterior pelvis anterior to the sacrum. Its actual Hounsfield measurements were consistent with fat. It contains a mural nodule (arrowhead) that has no contained calcification. Incidentally noted is a midpelvic mass (L) with calcifications, which was a leiomyoma. (From Cohen HL, Safriel YI. Benign cystic teratomas of the ovaries. In: Cohen HL, Sivit C, eds. Fetal and pediatric ultrasound: a casebook approach. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001:516.)

Overview and Imaging: Dysgerminoma is the second most common ovarian neoplasm in children and adolescents after mature teratoma. It is the most common malignant ovarian tumor of pediatric life but is considered a low-grade malignancy. It is said to be the histologic counterpart to the testicular seminoma of boys. Imaging or inspection shows it to be solid, smooth, and well encapsulated. These tumors often are large when first diagnosed. One fifth of cases have bilateral involvement. Dysgerminomas may arise in dysgenetic gonads, but this presentation is much less common than with gonadoblastomas. Pure dysgerminomas are nonfunctioning tumors, but function may be observed in germinomas that contain islands of other germ cell tumors. These tumors can spread locally and to retroperitoneal nodes. They are very radiosensitive, and prognosis with treatment is generally good, with an overall survival of more than 90%.1,50,51

Overview and Imaging: An endodermal sinus tumor (e.g., yolk sac tumor, yolk sac carcinoma, or Teilum tumor) is an uncommon malignant neoplasm that can occur at any age. It often is bulky at the time of diagnosis (Fig. 127-23) and is predominantly solid on ultrasound but may contain cystic spaces. In most cases, serum alpha-fetoprotein levels are increased. Some endodermal sinus tumors secrete human chorionic gonadotropin, causing incomplete precocious puberty by stimulating estrogen production by the ovary. This phenomenon can cause menstrual irregularities in postpubertal girls. The tumor is very radiosensitive. Although the incidence of recurrence is high, the survival rate is high among treated patients.1,54

Cystadenomas and Cystadenocarcinomas

Overview and Imaging: Surface epithelial tumors in children are similar to those in adults and consist predominantly of cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas. Cystadenomas are very uncommon before puberty and usually are unilateral. They vary in size from 3 to 30 cm. Of the two types of cystadenomas, serous cystadenomas contain clear watery fluid and the less common mucinous cystadenomas contain mucin, a jellylike material. Most of these tumors are multiseptated cystic masses (Fig. 127-24) when imaged by ultrasound. Cystadenomas are benign neoplasms, but a serous papillary form is reported to be prone to rupture, with spillage of tumor material into the peritoneal cavity, causing a serous papillomatosis. Cystadenocarcinomas are much less common than their benign counterparts. They may appear similar to cystadenomas, but the presence of irregular margins, thick septations, and papillary projections suggests malignancy. Ascites, omental or peritoneal implants, lymphadenopathy, and hepatic metastases indicate malignant spread.1,47,50

Figure 127-24 An ovarian cystadenoma.

A transverse sonogram in a teenager shows a large cystic mass (arrowheads) with several intersecting septations (arrows). This proved to be an ovarian cystadenoma, which is far more commonly seen in adults than in children. V, Vertebral body. (From Ruggierro M, Awobuluyi M, Cohen H, et al. Imaging the pediatric pelvis: role of ultrasound. Radiologist. 1997;4:155-170.)

Overview and Imaging: Granulosa/theca cell tumors generally are large at the time of diagnosis. They are predominantly solid, but mixed solid and cystic patterns or a predominantly cystic type also are seen. Three fourths of juvenile granulosa cell tumors produce estrogen, which causes isosexual precocious puberty. Nonfunctioning granulosa cell tumors may be discovered incidentally as a mass on physical examination or ultrasound. The vast majority of nonfunctioning granulosa cell tumors are benign, with recurrences and metastases a rarity.1,47,50

Arrhenoblastomas

Arrhenoblastomas (Leydig cell tumors) usually are large and unilateral. They may be solid or cystic. They usually are well differentiated and benign, but a poorly differentiated form also occurs. Most arrhenoblastomas produce androgenic substances, causing virilization in prepubertal girls and signs of virilization, hirsutism, and oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea after puberty.1,55

Capito, C, Echaieb, A, Lortat-Jacob, S, et al. Pitfalls in the diagnosis and management of obstructive uterovaginal duplication: a series of 32 cases. Pediatrics. 2008;122(4):e891–e897.

Chiou, SY, Lev-Toaff, AS, Masuda, E, et al. Adnexal torsion: new clinical and imaging observations by sonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26(10):1289–1301.

de Vries, L, Phillip, M. Role of pelvic ultrasound in girls with precocious puberty. Horm Res Paediatr. 2011;75(2):148–152.

Garel, L, Dubois, J, Grignon, A, et al. US of the pediatric female pelvis: a clinical perspective. Radiographics. 2001;21(6):1393–1407.

Lang, IM, Babyn, P, Oliver, GD. MR imaging of paediatric uterovaginal anomalies. Pediatr Radiol. 1999;29(3):163–170.

Ratani, RS, Cohen, HL, Fiore, E. Pediatric gynecologic ultrasound. Ultrasound Q. 2004;20(3):127–139.

Schultz, KA, Ness, KK, Nagarajan, R, et al. Adnexal masses in infancy and childhood. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;49(3):464–479.

Schultz, KA, Sencer, SF, Messinger, Y, et al. Pediatric ovarian tumors: a review of 67 cases. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2005;44(2):167–173.

Servaes, S, Victoria, T, Lovrenski, J, et al. Contemporary pediatric gynecologic imaging. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2010;31(2):116–140.

Shah, RU, Lawrence, C, Fickenscher, KA, et al. Imaging of pediatric pelvic neoplasms. Radiol Clin North Am. 2011;49(4):729–748. vi

Stranzinger, E, Strouse, PJ. Ultrasound of the pediatric female pelvis. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2008;29(2):98–113.

Ziereisen, F, Guissard, G, Damry, N, et al. Sonographic imaging of the paediatric female pelvis. Eur Radiol. 2005;15(7):1296–1309.

References

1. Cohen, HL. Abnormalities of the female genital tract. In Slovis T, ed.: Caffey’s pediatric diagnostic imaging, 11th ed, Philadelphia: Mosby (Elsevier), 2008.

2. Cohen, HL, Lemond, T. Gynecologic imaging of the pediatric patient. In: Fielding J, Brown D, Thurmond A, eds. Gynecologic imaging. Philadelphia: Saunders (Elsevier, 2011.

3. Cohen, HL, Bober, S, Bow, S. Imaging the pediatric pelvis: the normal and abnormal genital tract and simulators of its diseases. Urol Radiol. 1992;14:273.

4. Ruggierro, M, Awobuluyi, M, Cohen, H, et al. Imaging the pediatric pelvis: role of ultrasound. Radiologist. 1997;4:155.

5. Ratani, R, Cohen, HL, Fiore, E. Pediatric gynecologic ultrasound. Ultrasound Q. 2004;20:127.

6. Cohen, HL, Shapiro, MA, Mandel, FS, et al. Normal ovaries in neonates and infants: a sonographic study of 77 patients 1 day to 24 months old. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;160:583.

7. Currarino, G, Wood, B, Majd, M. Abnormalities of the genital tract. In Silverman F, Kuhn J, eds.: Caffey’s pediatric x-ray diagnosis, 9th ed, St Louis: Mosby–Year Book, 1993.

8. Herter, L, Golendziner, E, Flores, J, et al. Ovarian and uterine sonography in healthy girls between 1 and 13 years old: correlation of findings with age and pubertal status. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:1531.

9. Eisenberg, P, Cohen, H, Mandel, F, et al. US analysis of premenarchal gynecological structures. J Ultrasound Med. 1991;10:S30.

10. Salardi, S, Orsini, L, Cacciari, E, et al. Pelvic ultrasonography in premenarchal girls: relation to puberty and sex hormone concentrations. Arch Dis Child. 1985;60:120.

11. Cohen, HL, Tice, H, Mandel, F. Ovarian volumes measured by US: bigger than we think. Radiology. 1990;177:189.

12. Nussbaum Blask, AR, Sanders, RC, Gearhart, JP. Obstructed ureterovaginal anomalies: demonstration with sonography: I. Neonates and infants. Radiology. 1991;179:79.

13. Cohen HL, Sivit CJ, eds. Fetal and pediatric ultrasound: a casebook approach. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001.

14. Orsini, L, Salardi, S, Pilu, G, et al. Pelvic organs in premenarchal girls: real-time ultrasonography. Radiology. 1984;153:113.

15. Woodward, P, Sohaey, R, Wagner, B. Congenital uterine malformations. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 1995;24:177.

16. Emans, S, Laufer, M, Goldstein, D, The physiology of puberty. eds. Pediatric & adolescent gynecology, 5th ed, Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2005.

17. Caloia, D, Morris, H, Rahmani, M. Congenital transverse vaginal septum: vaginal hydrosonographic diagnosis. J Ultrasound Med. 1998;17:261.

18. Scanlan, KA, Pozniak, M, Fagerholm, M, et al. Value of transperineal sonography in the assessment of vaginal atresia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;154:545.

19. Reid, R. Amenorrhea. In: Copeland L, ed. Textbook of gynecology. Philadelphia: W B Saunders, 1993.

20. Reed, M, Griscom, N. Hydrometrocolpos in infancy. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1973;118:1.

21. Carrington, B, Hricak, H, Nuruddin, R, et al. Mullerian duct anomalies: MR imaging evaluation. Radiology. 1990;176:715.

22. Hugosson, C, Jorulf, H, Bakri, Y. MRI in distal vaginal atresia. Pediatr Radiol. 1991;21:281.

23. Rosenblatt, M, Rosenblatt, R, Kutcher, R, et al. Utero-vaginal hypoplasia: sonographic, embryologic and clinical considerations. Pediatr Radiol. 1991;21:536.

24. Reinhold, C, Hricak, H, Forstner, R, et al. Primary amenorrhea: evaluation with MR imaging. Radiology. 1997;203:383.

25. Fedele, L, Dorta, M, Brioschi, D, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;76:593.

26. Westrom, L. Incidence, prevalence and trends of acute pelvic inflammatory disease and its consequences in industrialized countries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980;138:880.

27. Cohen, HL, Smith, W, Kushner, D, et al. Imaging evaluation of acute right lower quadrant and pelvic pain in adolescent girls (ACR Appropriateness Criteria). Radiology. 2000;215S:833–840.

28. Bulas, D, Ahlstrom, P, Sivit, C, et al. Pelvic inflammatory disease in the adolescent: comparison of transabdominal and transvaginal sonographic evaluation. Radiology. 1992;183:435.

29. Linam, LE, Darolia, R, Naffaa, LN, et al. US findings of adnexal torsion in the pediatric and adolescent population: size really does matter. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37(10):1013–1019.

30. Servaes, S, Zurakowski, D, Laufer, MR, et al. Sonographic findings of ovarian torsion in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37:446–451.

31. Graif, M, Itzchak, Y. Sonographic evaluation of ovarian torsion in childhood and adolescence. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988;150:647.

32. Cil, A, Akgul, M, Tulunay, G, et al. Recovery of ovarian function after detorsion: Doppler findings. Acta Radiol. 2006;47:618.

33. Davis, AJ, Fein, NR. Subsequent asynchronous torsion of normal adnexa in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1990;25:687.

34. Fleischer, AC, Brader, KR. Sonographic depiction of ovarian vascularity and flow: current improvements and future applications. J Ultrasound Med. 2001;20:241.

35. Lee, E, Kwon, H, Joo, H, et al. Diagnosis of ovarian torsion with color Doppler sonography: depiction of twisted vascular pedicle. J Ultrasound Med. 1998;17:83.

36. Quillin, S, Siegel, M. Color Doppler ultrasound of children with acute lower abdominal pain. Radiographics. 1993;13:293.

37. Cohen, HL. Physiologic ovarian cysts in a newborn. In: Hertzberg B, Hill M, Cohen HL, eds. Ultrasound (third series): test and syllabus. Baltimore: ACR Publications, 2005.

38. Garel, L, Filiatrault, D, Brandt, M, et al. Antenatal diagnosis of ovarian cysts: natural history and therapeutic implications. Pediatr Radiol. 1991;21:182.

39. Cohen, HL, Eisenberg, P, Mandel, F, et al. Ovarian cysts are common in premenarchal girls: a sonographic study of 101 children 2 to 12 years of age. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159:89.

40. Galli-Tsinopoulou, A, Moudiou, T, Mamopoulos, A, et al. Multifollicular ovaries in female adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:1484.

41. Baltarowich, OH, Kurtz, A, Pasto, M, et al. The spectrum of sonographic findings in hemorrhagic ovarian cysts. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;148:901.

42. Herter, L, Magalnaes, J, Spritzer, P. Association of ovarian volume and serum LH levels in adolescent patients with menstrual disorders and/or hirsutism. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1993;26:1041.

43. Atiomo, W, Pearson, S, Shaw, S, et al. Ultrasound criteria in the diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Ultrasound Med Biol. 2000;26:977.

44. Takahashi, K, Okada, M, Ozaki, T, et al. Transvaginal ultrasonographic morphology in polycystic ovarian syndrome. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1995;39:201.

45. Battaglia, C, Artini, P, Genazzani, A, et al. Color Doppler analysis in oligo- and amenorrheic women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1997;11:105.

46. Pinkas, H, Mashiach, R, Rabinerson, D, et al. Doppler parameters of uterine and ovarian stromal blood flow in women with polycystic ovary syndrome and normally ovulating women undergoing controlled ovarian stimulation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1998;12:197.

47. Wu, A, Siegel, MJ. Sonography of pelvic masses in children: diagnostic predictability. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1987;148:1199.

48. Boechat, M. Magnetic resonance imaging of abdominal and pelvic masses in children. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 1990;3:25.

49. McNall, R, Nowicki, P, Miller, B, et al. Adenocarcinoma of the cervix and vagina in pediatric patients. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2004;43:289–294.

50. Surratt, J, Siegel, M. Imaging of pediatric ovarian masses. Radiographics. 1991;11:533.

51. Sisler, CL, Siegel, MJ. Ovarian teratomas: a comparison of the sonographic appearance in prepubertal and postpubertal girls. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;154:139.

52. Ulbright, T, Srigley, J. Dermoid cyst of the testis: a study of five postpubertal cases, including a pilomatrixoma-like variant, with evidence supporting its separate classification from mature testicular teratoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:788.

53. Ekici, E, Soysal, M, Kara, S, et al. The efficiency of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of dermoid cysts. Zentralbl Gynakol. 1996;118:136.

54. Levitin, A, Haller, K, Cohen, HL, et al. Endodermal sinus tumor of the ovary: imaging evaluation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167:791.

55. Larsen, W, Felmar, E, Wallace, M, et al. Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor of the ovary: a rare cause of amenorrhea. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79:831.