Chapter 21 Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

BACKGROUND AND DEFINITIONS

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) is among the most common diagnostic and therapeutic challenges faced by gynecologists. Complaints of AUB account for more than a third of gynecology visits.1 An indication of how difficult this problem can be to treat is that AUB remains the indication for half the hysterectomies performed in the United States. The inability to find any pathologic abnormality in 20% of these hysterectomy specimens suggests that AUB is often caused by potentially treatable hormonal or systemic conditions.2

Definition

Abnormal uterine bleeding is an all-inclusive term used to describe any uterine bleeding outside the parameters of normal menstruation that occurs during the reproductive years. It does not include bleeding that originates lower in the genital tract (i.e., the vagina or vulva). It usually does include bleeding originating from either the uterine fundus or cervix, because these causes are difficult to distinguish clinically, and should both be considered in all patients presenting with bleeding from the uterus. Abnormal bleeding can occur during childhood or after the menopause. However, because the differential diagnoses and thus the diagnostic approach are markedly different during these time periods, bleeding in these age groups is considered separately in Chapters 13 and 24.

Normal Menstruation

Exactly what is considered normal menstruation is somewhat subjective and often varies between individual women and certainly between cultures. However, normal menstruation (eumenorrhea) can be defined as bleeding that occurs after ovulatory cycles every 21 to 35 days, lasts 3 to 7 days, and is not excessive. The total amount of blood lost during a normal menstrual period has been found to be no more than 80mL, although this is difficult to estimate clinically, because much of the menstrual effluent is dissolved endometrium.3 Normal menses do not cause severe pain, do not include passage of identifiable clots, and do not require the patient to change pads or tampons more than once per hour. It follows that AUB is any bleeding that falls outside these parameters.

Abnormal Uterine Bleeding Terminology

The following descriptive terms are often used to describe AUB:

Dysfunctional Uterine Bleeding: An Obsolete Diagnostic Term

Dysfunctional uterine bleeding is a traditional term that was used for years to refer to excessive uterine bleeding in cases where no uterine pathology could be identified.4 However, the development of a greater understanding of AUB and the continuing development of more sophisticated diagnostic techniques has made this term outdated.

Clinically, treatment will always be the most effective when specific causes of AUB can be identified. Because grouping widely divergent causes of AUB together in a poorly defined group is unlikely to improve diagnosis or treatment, a national consensus group has recently concluded that dysfunctional uterine bleeding no longer has any usefulness in clinical medicine.5

ABNORMAL UTERINE BLEEDING CAUSED BY UTERINE CONDITIONS

Different causes of AUB can be grouped according to their basic pathophysiology (Tables 21-1 and 21-2). The clinician must keep in mind that any individual patient can simultaneously have two or more causes of uterine bleeding. For this reason, the workup must evaluate patients simultaneously for the most likely and most serious anatomic and systemic etiologies based on clinical presentation.

Table 21-1 Common Uterine Conditions Associated with Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

Table 21-2 Incidence of Endometrial Polyps and the Risk of Associated Malignancies as a Function of Age.

| Age Group (Years of age) | Incidence of Endometrial Polyps | Risk of Associated Malignancy |

|---|---|---|

| 25–35 | 9% | 2% |

| 36–45 | 27% | 11% |

| 46–55 | 29% | 15% |

| 56–65 | 18% | 17% |

| >65 | 17% | 55% |

Data from Hileeto D, Fadare O, Martel M, Zheng W: Age-dependent association of endometrial polyps with increased risk of cancer involvement. World J Surg Oncol 3:8, 2005.

Pregnancy

Normal pregnancies, spontaneous abortions, and ectopic pregnancies together represent the most common causes of AUB in the reproductive-age group. First-trimester bleeding occurs in up to 25% of all pregnancies and is associated with an increased risk of several common complications.6 In approximately half of these cases, bleeding will be an early symptom of impending spontaneous abortion, whereas the remaining half will ultimately prove to have a viable pregnancy. Ectopic pregnancies, which currently make up 2% of all pregnancies, will commonly present with AUB as one of the symptoms as well.7 Gestational trophoblastic disease is another pregnancy-related problem that presents as AUB in more than 80% of cases.8 Pregnancy must be ruled out in every case of AUB in reproductive-age women, no matter how obvious any alternative causal diagnoses might be.

Uterine Pathology

An important and expected priority for gynecologists is to precisely identify uterine pathology that might contribute to uterine bleeding (see Table 21-1). Most of these diagnoses can be determined to be related to infection and neoplasm. An additional common uterine pathology related to AUB is adenomyosis.

Infection

Infection is a surprisingly common cause of AUB and is often the basis of what appears to be AUB. In obvious cases of pelvic inflammatory disease (see Chapter 33), approximately 40% of the patients will present with vaginal bleeding.9 An underrecognized cause of uterine bleeding is endometritis. Although chronic endometritis was classically diagnosed only when plasma cells were found on endometrial biopsy, recent studies have found an association between AUB and reactive changes in the surface endometrium, but no association with the presence of a particular type of inflammatory cell.10 Other studies have verified that subclinical endometritis is a common finding in patients diagnosed with AUB and can be related to any of a number of pathogens.11

Cervicitis is another common cause of AUB characterized by postcoital spotting. In addition to common sexually transmitted diseases (i.e., chlamydia and gonorrhea), other vaginal flora and pathogens can be involved.12 Postcoital bleeding is the most common presenting symptom in women found to have chlamydia infections.13

Neoplasms

AUB can be a marker for gynecologic neoplasms. These neoplasms can be benign (e.g., leiomyoma, endometrial or endocervical polyps) or malignant (e.g., endometrial or cervical carcinoma). Focal intracavitary lesions account for up to 40% of cases of AUB.14 Ovarian neoplasms can indirectly cause irregular bleeding by interfering with ovulation Some of the most common neoplasms known to cause AUB are reviewed here.

Leiomyomas

These benign myometrial tumors are remarkably common and by age 50 can be found in nearly 70% of white women and more than 80% of black women on ultrasonographic examination.15 However, many of these leiomyomas are subclinical, and estimates of symptomatic leiomyomas range from 20% to 40%.

Endometrial Polyps

Endometrial polyps are localized overgrowths of the endometrium that project into the uterine cavity. Such polyps may be broad-based (sessile) or pedunculated. Endometrial polyps are surprisingly common in both premenopausal and postmenopausal women, and are found in at least 20% of women undergoing hysteroscopy or hysterectomy.16 The incidence of these polyps rises steadily with increasing age, peaks in the fifth decade of life, and gradually declines after menopause.

Studies have found that from 5% to 33% of premenopausal women complaining of AUB will be found to have endometrial polyps.17,18 Endometrial polyps are commonly found in patients with a long history of anovulatory bleeding, suggesting that polyps might be the result of chronic anovulation in some women. Polyps are also found in women complaining of postmenstrual spotting or bleeding in ovulatory cycles or during cyclic hormonal therapy.

Although endometrial polyps in premenopausal women are usually benign, the risk of associated endometrial malignancy increases significantly with age, such that in women older than age 65 the risk of malignancy is greater than 50% (see Table 21-2).16 In one pathologic study of 513 women with endometrial polyps, associated carcinomas were endometrioid in 58, serous in 6, carcinosarcoma in 1, and clear cell in 1.16

Endometrial Cancer

The single most important disease to identify early in the evaluation of a perimenopausal or postmenopausal woman is endometrial cancer. In women age 40 to 49, the incidence of endometrial carcinoma is 36 per 100,000.19 After the menopause, approximately 10% of women with AUB will be found to have endometrial cancer, and the incidence increases with each decade of life thereafter.

Endocervical Polyps

The cause of endocervical polyps is unclear, but they are known to be more frequent in women on oral contraceptives or with chronic cervicitis. Microscopically, endocervical polyps consist of a vascular core surrounded by a glandular mucous membrane and may be covered completely or partially with stratified squamous epithelium. In some cases, the connective tissue core may be relatively fibrous. Endocervical polyps removed from women taking oral contraceptives often show a pattern of microglandular hyperplasia.20

Cervical Cancer

As many as 17% of women presenting with postcoital spotting will be found to have cervical dysplasia; 4% will have invasive cancer.21 In the absence of a visible lesion, Papanicolaou smears and colposcopy (if indicated) are important diagnostic tools. In the presence of a visible cervical lesion, biopsy is the most important technique for confirming the clinical diagnosis.

Adenomyosis

Adenomyosis is the benign invasion of endometrium into the myometrium. Microscopic examination of the uterus reveals endometrial glands and stroma deep within the endometrium surrounded by hypertrophic and hyperplastic myometrium. This histopathologic diagnosis is made on careful microscopic evaluation of uterine specimens in more than 60% of hysterectomy specimens.22 Clinically, two thirds of patients with adenomyosis will complain of menorrhagia and dysmenorrhea, and pelvic examination usually reveals a diffusely enlarged and tender uterus.

Diagnostic tests that are suggestive of adenomyosis include transvaginal ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The sensitivity for ultrasonography probably approaches 50%, and the sensitivity of MRI ranges from 80% to 100%.22,23 Hopefully, more effective diagnostic tests and treatment besides hysterectomy will be developed in the future.

ABNORMAL UTERINE BLEEDING UNRELATED TO UTERINE PATHOLOGY

Many women experience heavy or irregular menstrual bleeding that is not caused by an underlying anatomic abnormality of the uterus. Although anovulatory bleeding is one of the most common underlying causes, a number of other unrelated causes, such as exogenous hormones and bleeding disorders, must also be considered (Table 21-3).

Table 21-3 Causes of Abnormal Uterine Bleeding Unrelated to Uterine Pathology*

* Referred to as “dysfunctional uterine bleeding” in the past.

Exogenous Hormones

Hormone Contraceptives

Today, approximately 10 million women in the United States use some type of hormonal contraception, including combination oral contraceptives, progestin-only pills, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate injections, progestin-containing intrauterine devices, subdermal levonorgestrel implants, transdermal combination hormone patches, and intravaginal rings (see Chapter 26). In addition to being a common reason to visit primary care physicians, AUB is a major cause of contraception discontinuation and subsequent unplanned pregnancy.

If abnormal bleeding persists beyond 3 months, other common causes should be excluded. In young sexually active women, sexually transmitted diseases should be excluded; in one study, almost one third of women on oral contraceptives who experienced abnormal bleeding were found to have otherwise asymptomatic Chlamydia trachomatis infections.24 If no cause for AUB other than hormonal therapy is found, treatment options include the use of supplemental estrogen and changing to an oral contraceptive with a different formulation with a different progestin or higher estrogen content (see Chapter 26).

Hormone Replacement Therapy

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) after the menopause is a common iatrogenic cause of AUB. Unopposed daily estrogen therapy is associated with the highest rates of irregular bleeding and subsequent discontinuation of therapy.25 The addition of sequential or continuous oral progestins is associated with decreased irregular bleeding and reduced rate of endometrial hyperplasia. Sequential progestins result in the lowest rate of irregular bleeding during the first year of therapy, but the rate for sequential and continuous therapy is similar thereafter.

Each selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) is associated with a distinctive risk of AUB, which varies according to their effect on the endometrium. Tamoxifen, the first SERM used clinically as adjuvant treatment for breast cancer, exhibits antiestrogenic activity in the breast but stimulates the endometrium.26 As a result, tamoxifen has an incidence of postmenopausal vaginal bleeding similar to unopposed estrogen and likewise increases the risk of endometrial pathology, including endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and cancer.

Raloxifene, a SERM approved for the prevention of osteoporosis, has little if any estrogenic effect on the uterus, resulting in atrophic endometrium.27 As a result, the risk of vaginal bleeding for women taking raloxifene is not increased compared to women not taking any form of HRT.

Ovulation Defects

Abnormal or absent ovulation is one of the most common causes of AUB during the reproductive years. A brief description of normal menstrual physiology (which is covered in depth in Chapter 1) is helpful in understanding anovulation as an underlying cause of AUB.

Normal Menstruation

Withdrawal of progesterone and estrogen results in menstruation, which involves the breakdown and uniform shedding of much of the functional layer of the endometrium, which is enzymatically dissolved by matrix metalloproteinases.28 Normal menses occur every 28±7 days, with duration of flow of 4±2 days and a blood loss of 40±40mL.29 Hemostasis is achieved by a combination of normal coagulation mechanisms and vasoconstriction of the spiral arterioles.

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

The most common causes of chronic anovulation are grouped together under a constellation of symptoms referred to as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) (see Chapter 15). PCOS is a heterogeneous endocrine and metabolic disorder that affects 6% to 10% of reproductive-age women.30 This syndrome is diagnosed when a woman without an underlying condition is found to have two out of the following three criteria: (1) oligo-ovulation or anovulation, (2) hyperandrogenism and/or hyperandrogenemia, and (3) polycystic ovaries.31 These women have circulating estrogen levels in the normal range but anovulatory progesterone levels.

Polycystic ovary syndrome is often the result of insulin resistance.30 In today’s culture, insulin resistance is often related to obesity. However, not all women with PCOS have insulin resistance and obesity. Insulin resistance is a common but not universal metabolic disorder underlying PCOS.32

The mechanism whereby insulin resistance results in PCOS is fascinating.33 Insulin increases production of androgens by both the ovaries (primarily androstenedione and testosterone) and adrenal gland (primarily dihydroepiandrosterone). In the ovary, insulin increases androgen secretion by thecal cells in an LH-dependent process and ovarian stroma cells. These increased androgens contribute to the hirsutism and may contribute to the increased body mass often seen in PCOS patients. These androgens can be aromatized peripherally in both fat and muscle to estrogens (primarily estrone), which acts on the pituitary to increase secretion of LH, which in turn stimulates the ovaries to secrete more androgens in concert with insulin. The resulting positive feedback loop is believed to be the cause of many cases of PCOS. The accuracy of this interpretation is supported by the observation that in many overweight patients, either weight loss or the use of an insulin-sensitizing agent (e.g., metformin) will simultaneously improve insulin resistance and restore regular ovulatory cycles.33

Systemic Diseases That Can Mimic PCOS

Conditions that can result in signs and symptoms identical to PCOS can be divided into two groups. The first group includes conditions that cause hyperandrogenemia, which can in turn interfere with ovulation and result in a clinical picture identical to PCOS.34 These include adult-onset congenital adrenal hyperplasia, Cushing’s syndrome and disease, and androgen-secreting neoplasms of the ovary or adrenal gland. Adult-onset congenital adrenal hyperplasia should be suspected whenever PCOS symptoms occur simultaneously with menarche. Cushing’s and androgen-secreting tumors should be suspected when hyperandrogenism and ovulation dysfunction present rapidly in a woman with previously normal menstrual cycles. Evaluation and management of these specific syndromes are discussed in Chapters 18 and 22.

The second group consists of any systemic condition that can interrupt ovulation. Both hypothyroidism and hyperprolactinemia are relatively common conditions that may have no symptoms other than interference with ovulation. Simple blood tests can screen for these conditions in the initial evaluation of apparent PCOS. In addition, any serious systemic disease can interfere with ovulation—most notably, renal failure and chronic liver disease. Both of these systemic disorders can affect hemostasis. Patients with serious systemic diseases usually manifest significant symptoms in addition to ovulatory dysfunction and AUB.35

Coagulopathy

Hereditary Bleeding Disorders

Von Willebrand’s disease and less common disorders of platelet function and fibrinolysis are characterized by excessive menstrual bleeding that begins at menarche and is usually regular. As many as 20% of adolescents who present with menorrhagia significant enough to cause anemia or hospitalization have a bleeding disorder, and thus should undergo an evaluation for coagulopathy. However, it is important to remember that most AUB in this age group is probably due to anovulation.36

The most common bleeding disorder is von Willebrand’s disease, which affects 1% to 2% of the population.37 This hereditary deficiency (or abnormality) of the von Willebrand factor (vWF) results in decreased platelet adherence. Von Willebrand factor interacts with platelets to form a platelet plug. A fibrin clot will then form on this plug. There are three main types of von Willebrand’s disease. The mild form (type 1) is responsible for more than 70% of cases and is an absolute decrease in the protein. The mechanism by which an abnormal factor leads to bleeding at the level of the endometrium is unclear. The vast majority of women with von Willebrand’s disease report AUB, specifically menorrhagia. The prevalence of this disorder in adult women with menorrhagia can range from 7% to 20%. Other inherited conditions include thrombocytopenias and rare clotting factor deficiencies (e.g., factor I, II, V, VII, X, XI, XIII deficiencies).

Anticoagulant Therapy

Excessive bleeding can sometimes be a significant problem for woman taking anticoagulant therapy, such as warfarin or heparin. Fortunately, most women taking anticoagulants do not have problems with AUB, which is considered to be an adverse reaction to anticoagulant therapy. Life-threatening genital bleeding in women taking anticoagulants is rare but may require emergency hysterectomy.38

CLINICAL EVALUATION OF ABNORMAL UTERINE BLEEDING

When evaluating a woman with AUB, the workup should be tailored according to age and presentation in order to be the most expedient and cost-effective (see Table 21-1). At the same time, the clinician must be aware of common causes of AUB that might not be clinically obvious but still must be excluded.

An important fact to keep in mind is that AUB can often have more than one cause. Sometimes subtle comorbid conditions, such as anovulation and secondary endometritis, make single-factor therapy surprisingly ineffective.11 In other women, obvious causes of chronic anovulation can be associated with endometrial hyperplasia and/or cancer. Careful evaluation of the patient for multiple simultaneous causes of AUB is requisite.

History

Characterization of Bleeding

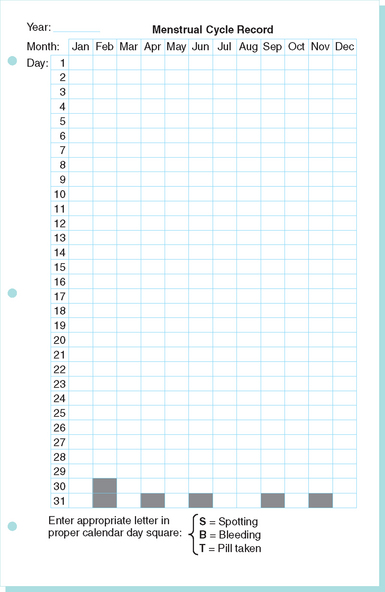

Once pregnancy is excluded, the amount and character of the bleeding is the most important information. Careful, stepwise retrospective questioning will usually give a clear picture of the bleeding pattern over the previous days, months, and even years. In nonemergency cases, the use of a prospective menstrual calendar is an excellent way to document the problem as well as the response to therapy (Fig. 21-1). It is important to determine when the bleeding problems were first noticed, because menorrhagia starting at menarche should alert the clinician to the possibility of an underlying bleeding disorder.

The amount of bleeding is probably the most difficult to determine, because normal or heavy menstrual bleeding can be very subjective. For research purposes, menorrhagia can be defined as a monthly blood loss of more than 80mL on three consecutive menses as measured by the alkali hematin method.39 Unfortunately, this type of accurate evaluation is neither cost-effective nor readily available.

Symptoms of Hemostatic Disorders

In adolescents with menorrhagia, it is important to determine any past history of excess bleeding during surgical, dental, or obstetric procedures because this has been found to be predictive of von Willebrand’s disease.40 Surprisingly, in this same study epistaxis and easy bruising were not clearly discriminatory symptoms.

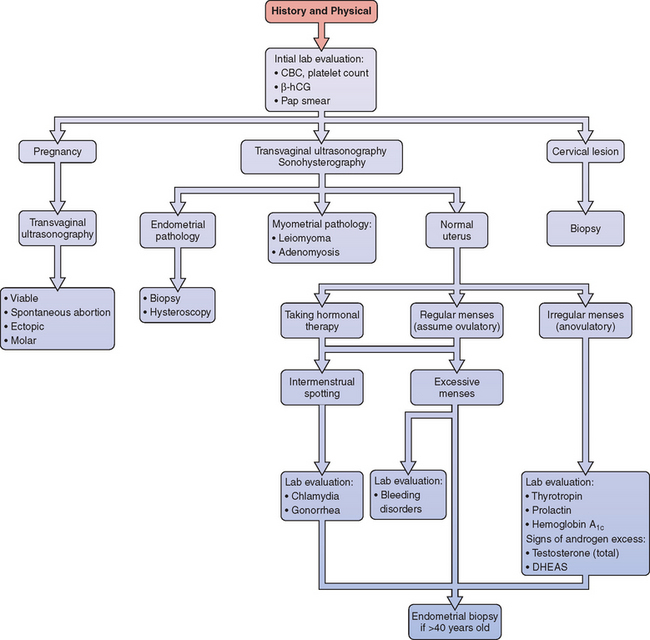

Laboratory Testing

Laboratory evaluation is an important part of the initial evaluation of all patients with AUB (Table 21-4). However, rather than ordering every possibly helpful test at the first visit, laboratory tests should be obtained in a stepwise fashion based on presentation (see Fig. 21-1).

Polycystic ovary syndrome and adult-onset congenital adrenal hyperplasia may sometimes be indistinguishable by clinical presentation, with both disorders often characterized by hirsutism, acne, menstrual abnormalities, and infertility.41 Unfortunately, no discriminatory screening test exists for this heterologous condition, most commonly caused by 21-hydroxylase or 11β-hydroxylase deficiency. If ovulation dysfunction and signs of androgen excess begin at the time of puberty, these women should be investigated appropriately (see Chapters 18 and 22).

Hemostatic Disorders

Patients with the new onset of significant menorrhagia should be evaluated for bleeding disorders with prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, and bleeding time.42 Any patient with a history of menorrhagia since menarche, especially with a history of surgical- or dental-related bleeding or postpartum hemorrhage, should be evaluated for hereditable bleeding disorders. These tests will include specific tests for von Willebrand’s disease such as vWF antigen, vWF functional activity (ristocetin cofactor activity), and factor VIII level. These levels can fluctuate; therefore, the tests should be repeated if clinical suspicion is high. Normal ranges should be adjusted for the observation that vWF levels are 25% lower in women with blood type O compared with other blood groups. Some centers offer a screening test referred to as a “platelet function assay” before performing detailed von Willebrand testing. Further studies such as platelet aggregation studies may be required.42 If these studies are negative, factor XI level and euglobulin clot lysis time can be evaluated.

Malignancies and Premalignancies

Endometrial Biopsy

The incidence of endometrial carcinoma in women between ages 40 and 49 has been reported to be as high as 36 per 100,000.43 The risk after menopause continues to increase. For this reason, once pregnancy has been excluded, an endometrial biopsy should be obtained in all women older than age 40 who present with AUB.

Imaging and Hysteroscopy

Transvaginal Ultrasonography

Today, transvaginal ultrasonography and sonohysterography has made unexpected findings at surgery rare (see Chapter 30). Ultrasonography and sonohysterography have become an important step in the evaluation of AUB (Fig. 21-2). Transvaginal ultrasonography can accurately determine uterine size and configuration, and can reveal the nature of both palpable and nonpalpable adnexal masses. Knowledge before surgery about the size and location of leiomyoma and the potential that an ovarian mass might be malignant is invaluable.

Office Hysteroscopy

Office hysteroscopy (see Chapter 42) is another excellent outpatient method for visualizing the uterine cavity. The discomfort and risk is also somewhat greater than with sonohysterography, and the procedure can be difficult in the presence of cervical stenosis or when the cervix is difficult to visualize. However, the color photographs of the lesion can be very instructive for patients.

MANAGEMENT OF ABNORMAL UTERINE BLEEDING

Treatment of AUB Unrelated to Pregnancy or Uterine Pathology

When pregnancy or a uterine condition is found to be the cause of AUB, specific treatment options are required that are described in other chapters. In more than half the cases, it will be determined that the bleeding is unrelated to pregnancy or uterine abnormalities. Treatment for these cases consists of correcting any underlying systemic abnormalities when possible and returning the endometrium to a functional status with exogenous hormone therapy when necessary. The simplest case might be hypothyroidism, where simple thyroid hormone replacement will restore normal ovulation in most cases (see Chapter 22). Hyperprolactinemia requires careful evaluation and monitoring (see Chapter 22). In some cases, what appears clinically as PCOS is actually an adrenal enzyme deficiency that can be treated with steroid replacement (see Chapter 22). As noted below in the section “Ovulation Induction,” even idiopathic PCOS can often be treated as a systemic condition related to insulin resistance.

Treatment of Women with Coagulopathy

Women with von Willebrand’s disease who complain of menorrhagia can often be successfully treated with long-term oral contraceptive therapy.43 Other medical treatments used by hematologists for acute episodes include desmopressin acetate, antifibrinolytic agents, and plasma-derived concentrates of vWF.43

Emergency Treatment of Anovulatory Bleeding

Dilation and Curettage

In cases where massive uterine bleeding is life-threatening, D&C is the most expedient way to stop blood flow and determine the existence of endometrial pathology when present. The disadvantage of this surgical approach is risk of anesthesia, which is dependent on the patient’s overall medical condition, and the small surgical risk. Although cost should always be a consideration in modern medicine, the usually fast and effective resolution of bleeding often allows discharge within 24 hours. Thus, the cost of surgery may actually be less than the cost of several days’ hospitalization required for the medical treatment discussed in the following. However, D&C has no long-term therapeutic effect; therefore, long-term treatment must be initiated. In most cases of AUB, medical management can be safely used as the first line of treatment.

Intravenous Estrogen Therapy

In many cases where the bleeding is not dangerously brisk, it can be improved overnight by administration of intravenous conjugated estrogens, 25mg given every 4 hours until bleeding stops. When studied in adolescents, it was found that intravenous conjugated estrogen therapy stopped acute bleeding in 90% of cases.36 Those that do not show signs of improvement in their bleeding within 8 hours required D&C.

This therapy might seem paradoxical for use in anyone who is bleeding because of prolonged unopposed estrogen effect on the endometrium. However, its effectiveness has been demonstrated in a well-designed study. In theory, estrogen acutely decreases uterine bleeding related to asynchronous shedding by stimulating clotting at capillary level and promoting vasoconstriction of spiral vessels.

Oral High-Dose Combined Hormonal Therapy

Once bleeding has slowed to that consistent with heavy menses or less, “taper” therapy with oral contraceptives can be started (Table 21-5). This approach is also ideal for women with heavy bleeding who do not require hospitalization for stabilization and observation. Like the intravenous estrogen therapy, nausea is a common problem with this treatment and should be treated preemptively with oral antiemetics to optimize compliance.

Table 21-5 “Taper” Oral Contraceptive Therapy for Abnormal Uterine Bleeding*

| Day | Frequency |

|---|---|

| 1–2 | One tablet 4 times daily |

| 3–4 | One tablet 3 times daily |

| 5–19 | One tablet daily |

| 20–25 | Expect menses |

| 26 | Start oral contraceptives at standard dosage |

* Regimen for low-dose (30 mcg ethinyl estradiol), monophasic oral contraceptives

Women at Increased Risk for Cardiovascular Disease or Venous Thrombosis

It is well appreciated that estrogen-containing oral contraceptives are relatively contraindicated in any women at increased risk for cardiovascular disease or venous thrombosis. This includes women with a history of thromboembolic disease and woman over age 35 who have additional risk factors (e.g., cigarette smoking, hypertension, diabetes). Although no studies have been published using short-term, high-dose intravenous or oral estrogen in these patients, at least one case of fatal pulmonary thromboembolism has been reported with intravenous therapy.44 Certainly, high-dose estrogen therapy should be used in these patients only if the benefits outweigh the risks.

Long-term Treatment of AUB

Subclinical Endometritis

It has been recently observed that the most frequent histologic finding in endometrial biopsies of women with AUB is chronic endometritis.45 This suggests that when apparently anovulatory AUB does not respond to progestin withdrawal, subclinical endometritis might be a coexisting disorder that must be addressed.

Although few studies have evaluated the role of subclinical endometritis in AUB, several have suggested a relationship. In one study, 81% of patients with irregular bleeding or vaginal discharge had positive endometrial cultures for Mobiluncus, and treatment with metronidazole resolved their irregular bleeding.46 In another study of 100 hysterectomies performed for irregular bleeding or fibroids, 25% of the endometrial cavities were found to harbor organisms, including Gardnerella vaginalis, Enterobacter, and Streptococcus agalactiae.47 Finally, a study of college-age women presenting with abnormal bleeding while on oral contraceptives found that 29% were infected with Chlamydia.48

Ovulation Induction

When fertility is desired, restoration of ovulation is paramount. This can be accomplished in many cases by restoring the hormonal milieu to a more normal state. In the case of hyperprolactinemia, lowering prolactin levels with the use of a dopamine agonist will often result in ovulation and pregnancy (see Chapter 22). In the case of PCOS, recent studies have demonstrated that lowering insulin levels with an insulin-sensitizing drug (e.g., metformin hydrochloride) will often restore ovulation and result in pregnancy in many cases (see Chapter 37).

While waiting for these therapies to result in resumption of ovulation and normal menses, monthly induction of withdrawal bleeding with oral progestin is important to avoid continued AUB. In women not using contraceptives, the use of micronized progesterone (100 to 200mg daily for 14 days) will result in reasonable withdrawal bleeding and be safe should pregnancy occur. For patients who do not resume ovulation with systemic therapy, induction of ovulation is attempted using clomiphene citrate or injectable medications as required (see Chapter 37).

Oral Contraceptives

Combination oral contraceptives have been used for decades to decrease both the duration and amount of menstrual flow and dysmenorrhea.49 More recently, it has been found that extending the number of consecutive days of active pills could decrease the annual number of menses, thus minimizing menstrual-related symptoms even further.50 A consequence of this is the marketing of extended-cycle oral contraceptives that have 3 months of active pills instead of 3 weeks and thus extend the time between menses, such that the patient only has 4 cycles per year. Unfortunately, this regimen has greater risk of spotting and breakthrough bleeding than those using monthly cycles.

Progestins

In menorrhagia (ovulatory AUB) luteal phase progestins have been shown to be less effective than other medications, including NSAIDs. Longer courses such as 21 days of therapy may be required.51 Luteal phase progestin therapy is less effective than tranexamic acid, danazol, or the progesterone-releasing intrauterine system (IUS). Progestin therapy for 21 days of the cycle (e.g., day 5 to day 26) is more effective.

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs

NSAIDs have long been used to reduce dysmenorrhea as well as the amount of menstrual flow, at least in part by inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis.52 Although studies are limited, NSAIDs appear to be an effective way to treat AUB in ovulatory women (menorrhagia). NSAIDs should not be used for women with von Willebrand’s disease or a platelet dysfunction.

Levonorgestrel-Containing Intrauterine System

The levonorgestrel-containing IUS, developed originally for contraception, is effective for the treatment of both menorrhagia and dysmenorrhea (see Chapter 27). The local release of levonorgestrel into the uterine cavity suppresses endometrial growth and has been shown to decrease menstrual blood loss by as much as 97%.53 Although many women complain of intermenstrual bleeding during the first few months of use, as many as 20% will have amenorrhea after a year. Even though the progestins are administered locally, some women complain of systemic side effects, such as breast tenderness. Although the initial cost of the levonorgestrel-containing IUS is high compared to other medical treatment, these devices are now approved for 10 years of uninterrupted use and are thus very cost-effective for long-term therapy.

Hormone Replacement Therapy

Some women older than age 40 with ovulatory dysfunction will also complain of symptoms of reduced estrogen production, such as hot flashes or sleep disturbances. Many of these women treated with continuous estrogen and cyclic progestin therapy will obtain symptomatic relief; up to 90% will respond with predictable progesterone withdrawal bleeding.54 The potential increased risk of venous thrombosis, cardiovascular disease, and breast cancer should be discussed with the patient.

Surgical Treatment for Abnormal Uterine Bleeding without Uterine Pathology

If medical management of AUB is unsuccessful and the woman is not interested in childbearing, surgical therapies, including endometrial ablation and hysterectomy, are often utilized. Endometrial ablation is the least invasive surgical procedure available and has been shown to result in less morbidity and shorter recovery periods and be more cost-effective than hysterectomy in the short term (see Chapter 42). Because women who undergo endometrial ablation can have residual active endometrium, they should receive progestin if they are prescribed estrogen hormone replacement therapy after menopause.

Hysterectomy remains a reasonable option for some women with AUB who fail medical management. As many as 20% of women who undergo endometrial ablation will subsequently undergo hysterectomy within 5 years, and some studies demonstrated a higher satisfaction rate in women who initially underwent hysterectomy rather than endometrial ablation.55,56

CONCLUSION

1 Coulter A, Bradlow J, Agass M, et al. Outcomes of referrals to gynaecology outpatient clinics for menstrual problems: An audit of general practice records. BJOG. 1991;98:789-796.

2 Carlson KJ, Nichols DH, Schiff I. Indications for hysterectomy. NEJM. 1993;328:856-860.

3 Fraser IS. Menorrhagia—a pragmatic approach to the understanding of causes and the need for investigations. BJOG. 1994;101(Suppl 11):3-7.

4 Bayer SR, DeCherney AH. Clinical manifestations and treatment of dysfunctional uterine bleeding. JAMA. 1993;269:1823-1828.

5 Fraser IS, Critchley HOD, Munro MG, Broder M. A process designed to lead to international agreement on terminologies and definitions used to describe abnormalities of menstrual bleeding. Fertil Steril. 2007.

6 Falco P, Zagonari S, Gabrielli S, et al. Sonography of pregnancies with first-trimester bleeding and a small intrauterine gestational sac without a demonstrable embryo. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;21:62-65.

7 Barnhart K, Esposito M, Coutifaris C. An update on the medical treatment of ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2000;27:653-667.

8 Soto-Wright V, Bernstein M, Goldstein DP, Berkowitz RS. The changing clinical presentation of complete molar pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;86:775-779.

9 Eschenbach DA. Acute pelvic inflammatory disease: Etiology, risk factors and pathogenesis. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1976;19:147-169.

10 Heatley MK. The association between clinical and pathological features in histologically identified chronic endometritis. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;24:801-803.

11 Eckert LO, Thwin SS, Hillier SL, et al. The antimicrobial treatment of subacute endometritis: A proof of concept study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:305-313.

12 Marrazzo JM, Handsfield HH, Whittington WL. Predicting chlamydial and gonococcal cervical infection: Implications for management of cervicitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:579-584.

13 Gotz HM, van Bergen JE, Veldhuijzen IK, et al. A prediction rule for selective screening of Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81:24-30.

14 Jones H. Clinical pathway for evaluating women with abnormal uterine bleeding. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2002;57:22-24.

15 Day Baird D, Dunson DB, Hill MC, et al. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: Ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:100-107.

16 Hileeto D, Fadare O, Martel M, Zheng W. Age dependent association of endometrial polyps with increased risk of cancer involvement. World J Surg Oncol. 2005;3:8.

17 Breitkopf DM, Frederickson RA, Snyder RR. Detection of benign endometrial masses by endometrial stripe measurement in premenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:120-125.

18 Clevenger-Hoeft M, Syrop CH, Stovall DW, Van Voorhis BJ. Sonohysterography in premenopausal women with and without abnormal bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:516.

19 ACOG Committee Opinion. Von Willebrand’s disease in gynecologic practice. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:1185-1186.

20 Young RH, Clement PB. Pseudoneoplastic glandular lesions of the uterine cervix. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1991;8:234-249.

21 Rosenthal AN, Panoskaltsis T, Smith T, Soutter WP. The frequency of significant pathology in women attending a general gynaecological service for postcoital bleeding. BJOG. 2001;108:103-106.

22 Matalliotakis IM, Kourtis AI, Panidis DK. Adenomyosis. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2003;30:63-82.

23 Bazot M, Cortez A, Darai E, et al. Ultrasonography compared with magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: Correlation with histopathology. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:2427-2433.

24 Krettek JE, Arkin SI, Chaisilwattana P, Monif GR. Chlamydia trachomatis in patients who used oral contraceptives and had intermenstrual spotting. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:728-731.

25 Lethaby A, Suckling J, Barlow D, et al. Hormone replacement therapy in postmenopausal women: Endometrial hyperplasia and irregular bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3, 2004. CD000402,

26 Barakat RR, Gilewski TA, Almadrones L, et al. Effect of adjuvant tamoxifen on the endometrium of women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3459-3463.

27 Tsalikis T, Zepiridis L, Zafrakas M, et al. Endometrial lesions causing uterine bleeding in postmenopausal women receiving raloxifene. Maturitas. 2005;51:215-218.

28 Zhang J, Salamonsen LA. In vivo evidence for active matrix metalloproteinases in human endometrium supports their role in tissue breakdown at menstruation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2346-2351.

29 Brenner PF. Differential diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:766-769.

30 Tsilchorozidou T, Overton C, Conway GS. The pathophysiology of polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2004;60:1-17.

31 Zawadski JK, Dunaif A. Diagnostic criteria for polycystic ovary syndrome: Towards a rational approach. In: Dunaif A, Givens JR, Haseltine FP, Merriam GE, editors. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Boston: Blackwell Scientific; 1992:377-384.

32 Lakhani K, Prelevic G, Seifalian A, et al. Polycystic ovary syndrome, diabetes and cardiovascular disease: Risks and risk factors. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;24:613-621.

33 Pugeat M, Ducluzeau PH. Insulin resistance, polycystic ovary syndrome and metformin. Drugs. 1999;58(Suppl 1):41-46.

34 Chang RJ. A practical approach to the diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:713-717.

35 Holley JL. The hypothalamic-pituitary axis in men and women with chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2004;11:337-341.

36 Falcone T, Desjardins C, Bourque J, et al. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding in adolescents. J Reprod Med. 1994;39:761-764.

37 Bravender T, Emans SJ. Menstrual disorders: Dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1999;46:545-553.

38 Minakuchi K, Hirai K, Kawamura N, et al. Case of hemorrhagic shock due to hypermenorrhea during anticoagulant therapy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2000;264:99-100.

39 Woo YL, White B, Corbally R, et al. Von Willebrand’s disease: An important cause of dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2002;13:89-93.

40 Kouides PA. Menorrhagia from a haematologist’s point of view. Part I: Initial evaluation. Haemophilia. 2002;8:330-338.

41 Sahin Y, Kelestimur F. The frequency of late-onset 21-hydroxylase and 11 β-hydroxylase deficiency in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 1997;137:670-674.

42 Kouides PA. Evaluation of abnormal bleeding in women. Curr Hematol Rep. 2002;1:11-18.

43 ACOG Practice Bulletin. Management of anovulatory bleeding. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001;72:263-271.

44 Zreik TG, Odunsi K, Cass I, et al. A case of fatal pulmonary thromboembolism associated with the use of intravenous estrogen therapy. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:373-375.

45 Ferenczy A. Pathophysiology of endometrial bleeding. Maturitas. 2003;45:1-14.

46 Larsson PG, Bergman B, Forsum U, Pahlson C. Treatment of bacterial vaginosis in women with vaginal bleeding complications or discharge and harboring Mobiluncus.. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1990;29:296-300.

47 Moller BR, Kristiansen FV, Thorsen P, et al. Sterility of the uterine cavity. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1995;74:216-219.

48 Krettek JE, Arkin SI, Chaisilwattana P, Monif GR. Chlamydia trachomatis in patients who used oral contraceptives and had intermenstrual spotting. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:728-731.

49 Sulak PJ. The career woman and oral contraceptive use. Int J Fertil. 1991;36(Suppl 2):90-97.

50 Sulak PJ, Cressman BE, Waldrop E, et al. Extending the duration of active oral contraceptive pills to manage hormone withdrawal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:179-183.

51 Lethaby A, Irbine G, Cameron I. Cyclical progestogens for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3, 2005. CD001016.

52 Higham JM. The medical management of menorrhagia. Br J Hosp Med. 1991;45:19-21.

53 Hurskainen R, Teperi J, Rissanen P, et al. Clinical outcomes and costs with the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system or hysterectomy for treatment of menorrhagia: Randomized trial 5 year follow up. JAMA. 2004;291:1456-1463.

54 Strickland DM, Hammond TL. Postmenopausal estrogen replacement in a large gynecologic practice. Am J Gynecol Health. 1988;2:26-31.

55 Comino R, Torrejon R. Hysterectomy after endometrial ablation-resection. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2004;11:495-499.

56 Lethaby A, Shepperd S, Cooke I, Farquhar C. Endometrial resection and ablation versus hysterectomy for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000. CD000329.