Abnormal Pulmonary and Systemic Venous Connections

Partial Anomalous Pulmonary Venous Connection and Scimitar Syndrome

Overview: Partial anomalous pulmonary venous connection (PAPVC) is present when one or more pulmonary veins drain into a systemic vein. Because a single anomalous connection may be unrecognized, the incidence is difficult to establish, but it has been reported to be present in one in 200 postmortem examinations.1,2

Etiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Presentation: All pulmonary veins from one lung may have anomalous drainage, or parts of the lung may have anomalous drainage to the same or different systemic veins. Anomalous drainage of the left pulmonary veins is most often to the brachiocephalic vein or coronary sinus.3 On the right, anomalous drainage is most often to the superior vena cava (SVC), right atrium, and inferior vena cava (IVC).4 When there is anomalous pulmonary venous drainage of all the right pulmonary veins, or just the middle and lower lobe veins to the IVC, scimitar syndrome is present. Other anomalies associated with scimitar syndrome include hypoplasia of the right lung and bronchial system, hypoplasia of the right pulmonary artery, systemic arterial supply to the right lower lung, and pulmonary sequestration.5–8

Approximately 67% of patients with partial anomalous pulmonary venous return also have atrial-level defects, most commonly a sinus venosus defect (see Chapter 73).9 Sinus venosus defects are not true atrial septal defects (ASDs) but occur as a result of deficiency of the wall between the SVC and the right upper pulmonary veins or of the wall between the right atrium and the right upper and lower pulmonary veins. Thus although a sinus venosus defect does not represent an abnormal pulmonary venous connection with a systemic vein, a superior sinus venosus defect often is associated with anomalous drainage of the right pulmonary veins to the SVC or to the right atrium.

With an intact atrial septum, the amount of blood draining through anomalous veins depends on the number of anomalous draining veins, the compliance of the atria, and the resistance of the pulmonary vascular beds. Anomalous connection of one pulmonary vein usually is not clinically apparent in childhood, but these patients may present in the third and fourth decades with cyanosis resulting from increased pulmonary vascular resistance.10 If all but one of the pulmonary veins drains anomalously, the clinical manifestations may be similar to total anomalous pulmonary venous connection. If they are associated with a sinus venosus septal defect, signs and symptoms usually are related to the amount of shunting through the defect. Patients with scimitar syndrome may present in infancy with pulmonary hypertension from the arterial supply to the right lower lung, stenosis of the anomalous pulmonary veins, or pulmonary infections. Otherwise, this syndrome may be detected in adulthood in persons who do not have significant symptoms.11

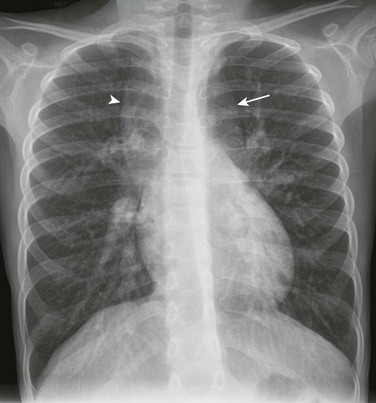

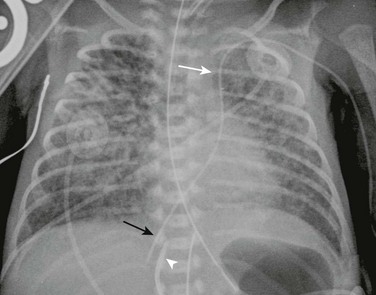

Imaging: With anomalous drainage of multiple veins, cardiomegaly with right heart enlargement and increased pulmonary flow are seen on chest radiography. Findings with scimitar syndrome include a crescent-shaped anomalous pulmonary vein (resembling a Turkish sword or scimitar) paralleling the lower right heart border (Fig. 72-1). Patients generally have associated hypoplasia of the right lung, a small right pulmonary artery, and varying degrees of cardiac dextroposition.

Figure 72-1 Scimitar syndrome.

A frontal chest radiograph shows the rightward shift of the mediastinum as a result of right lung hypoplasia. In the right side of the chest, a linear density indicative of the anomalous draining “scimitar” vein is seen (arrows).

Cross-sectional imaging goals include identifying the anomalous pulmonary to systemic venous connection, locating each pulmonary vein and its drainage relative to the left atrium, and determining the location of venous obstruction, if present (e-Fig. 72-2). Evaluation for the presence and size of either an ASD or sinus venosus defect, is necessary (e-Figs. 72-3 and 72-4). The heart and great vessels are evaluated for other abnormalities, and when scimitar syndrome is present, the upper abdomen should be assessed for anomalous venous drainage and systemic supply to the lung (Fig. 72-5). Both computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are highly sensitive and specific for evaluation of anomalous pulmonary venous drainage, and three-dimensional CT or magnetic resonance angiography is very useful for identifying the relationship between the anomalous pulmonary veins and the left atrium.12,13 MRI also is useful for ASD evaluation and for quantification of systemic to pulmonary shunting. CT and MRI are accurate in assessing for postoperative pulmonary vein obstruction or narrowing (e-Fig. 72-6).13–15

Figure 72-5 Scimitar syndrome.

A three-dimensional magnetic resonance angiogram viewed from right posterior oblique shows the anomalously draining right pulmonary “scimitar” vein (asterisk) extending to the inferior vena cava.

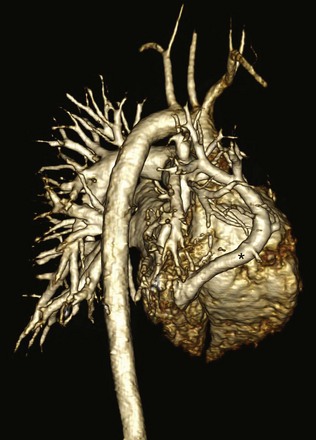

e-Figure 72-2 Partial anomalous pulmonary venous connection (PAPVC).

A three-dimensional magnetic resonance angiogram viewed from the left anterior oblique projection shows the PAPVC (arrow head) from the left upper lobe with drainage to the left brachiocephalic vein (BCV).

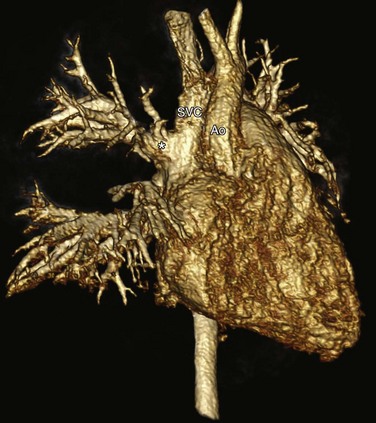

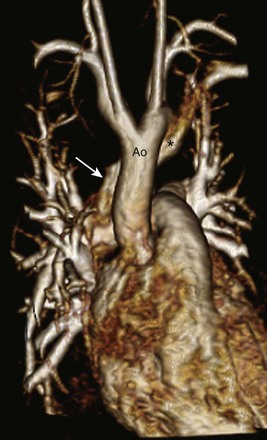

e-Figure 72-3 Partial anomalous pulmonary venous return in the setting of a superior sinus venosus defect.

A right anterior oblique three-dimensional magnetic resonance angiogram shows the right upper pulmonary veins (asterisk) draining to the SVC. SVC, Superior vena cava; Ao, aorta.

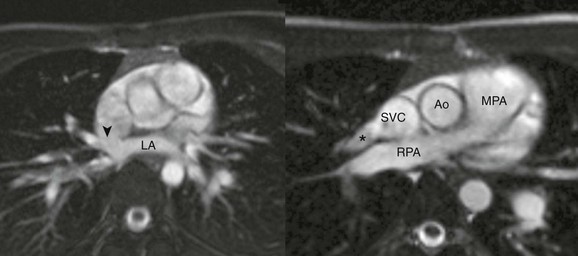

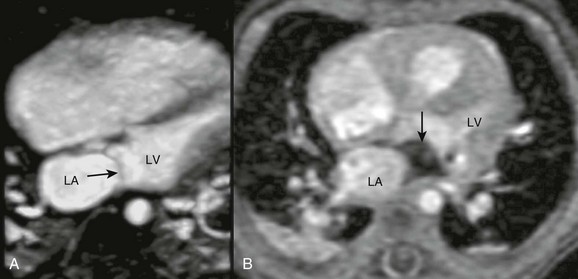

e-Figure 72-4 Sinus venosus defect with partial anomalous pulmonary venous return.

A, An axial cine steady-state free-precession (SSFP) image shows the sinus venosus defect (arrowhead) located superior to the expected location of the oval fossa, consistent with a superior sinus venosus defect. B, Oblique axial SSFP located superior to (A) showing the right upper pulmonary vein (asterisk) draining to the superior vena cava. Ao, Aorta; LA, Left atrium; MPA, main pulmonary artery; RPA, right pulmonary artery; SVC, superior vena cava.

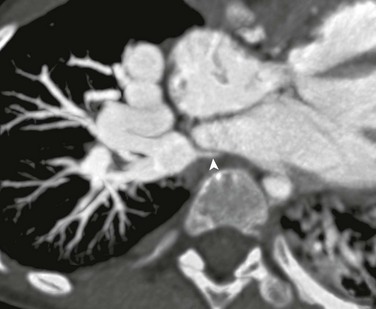

e-Figure 72-6 Severe right pulmonary vein stenosis.

A computed tomography axial oblique reformat 5 years after repair of obstructed supracardiac total anomalous pulmonary venous connection with separate anastomoses of the right and left pulmonary veins to the left atrium. Severe right pulmonary vein stenosis (arrowhead) is present at the anastomotic site.

Treatment: Surgical correction is indicated when the ratio of pulmonary to systemic arterial flow is greater than 1.5 : 1; outcomes generally are excellent.4 In patients with scimitar syndrome, pulmonary resection or catheter occlusion of the anomalous arterial blood supply may be necessary. The anomalous vein in patients with scimitar syndrome may be anastomosed directly to the left atrium.

Superior sinus venosus defects may be closed with a patch at the junction of the SVC and right atrium, with baffling of the pulmonary venous return to the left atrium. Alternatively, the SVC is divided above the pulmonary veins, with implantation of the SVC to the right atrial appendage and baffling of the SVC orifice with the right pulmonary venous return to the left atrium. The incidence of postoperative SVC or pulmonary vein stenosis is less than 10%.16

Total Anomalous Pulmonary Venous Connection

Overview: Total anomalous pulmonary venous connection (TAPVC) is a congenital anomaly in which all of the pulmonary veins connect to the systemic venous circulation rather than to the left atrium. TAPVC accounts for approximately 1% to 5% of all congenital heart disease,17,18 with a male predominance when the anomalous connection is to the portal vein.19 TAPVC often is present in patients with visceral heterotaxy and asplenia and single-ventricle physiology.18

Etiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Presentation: The cause of TAPVC is thought to be lack of incorporation of the common pulmonary vein into the left atrium. In type I or supracardiac TAPVC (49% of cases), all four pulmonary veins join to form a confluent pulmonary vein posterior to the left atrium and then most commonly connect to a persistent left vertical vein, which drains to the left brachiocephalic vein and to the right SVC or via the right ascending vein to the right SVC. In type II or cardiac TAPVC (16% of cases), the pulmonary veins form a confluence that drains either directly into the right atrium or to the coronary sinus, which then drains normally into the right atrium. In type III or infracardiac TAPVC (26% of cases), the pulmonary veins converge as a common pulmonary vein that extends below the diaphragm and drains to the portal vein, ductus venosus, hepatic vein, or IVC. Type IV TAPVC (9% of cases) is a mixed type in which the pulmonary veins drain separately to at least two different systemic sites, most commonly supracardiac and cardiac sites (e-Fig. 72-7 and Fig. 72-8).20

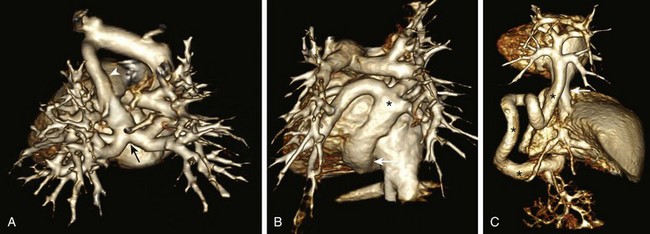

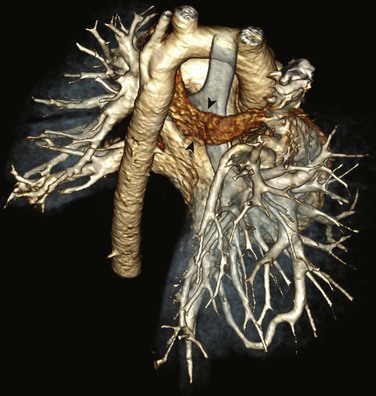

Figure 72-8 Three-dimensional computed tomography angiogram posterior views of different types of total anomalous pulmonary venous connection (TAPVC).

A, Supracardiac TAPVC. The pulmonary venous confluence (arrow) connects to the ascending vertical vein (arrowhead), the brachiocephalic vein, and the enlarged superior vena cava. B, Cardiac TAPVC. The pulmonary venous confluence (asterisk) connects to the coronary sinus (arrow). C, Infracardiac TAPVC. The pulmonary venous confluence extends below the diaphragm via a tortuous descending vertical vein (asterisks) to connect with the portal vein (arrow) inferior vena cava.

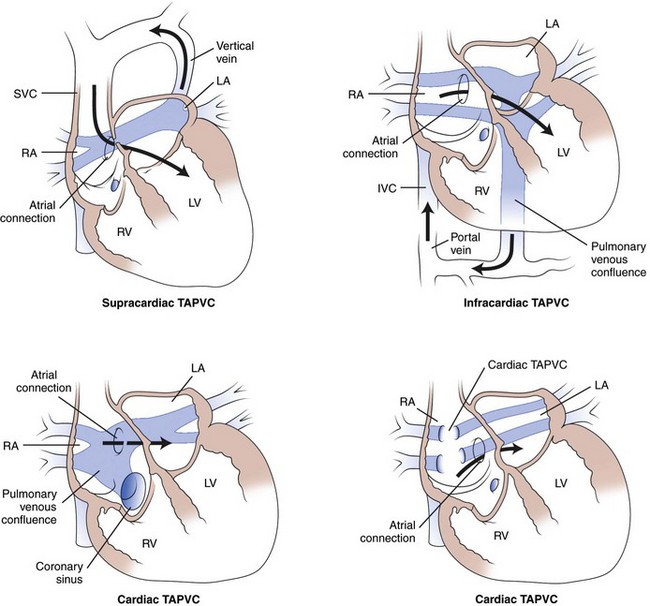

e-Figure 72-7 Darling classification of total anomalous pulmonary venous connection (TAPVC).

With supracardiac TAPVC, pulmonary venous connection is to a vertical vein, draining to the left brachiocephalic vein and superior vena cava (SVC). With infracardiac TAPVC, the pulmonary veins connect to a systemic venous vessel below the diaphragm (the portal vein in this diagram). With cardiac TAPVC, the pulmonary veins connect either to the coronary sinus or directly to the right atrium (RA). The direction of systemic blood flow (dark arrows) is shown. Note that blood must flow through an atrial connection to reach the left side of the heart. IVC, Inferior vena cava; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle. (From Wilson A. Total anomalous pulmonary venous connection, E-Medicine, March 28, 2006.)

Obstruction occurs in 46% of patients with supracardiac TAPVC as the left vertical vein passes between the left pulmonary artery and left mainstem bronchus or as the right vertical vein crosses between the right pulmonary artery and right mainstem bronchus or at its entrance into the right SVC.17,20 With cardiac TAPVC, obstruction is not nearly as frequent (20%).20 With infracardiac TAPVC, obstruction is common (87%) and can occur at the level of the diaphragm and/or at the site of anomalous systemic venous insertion, including the ductus venosus or the hepatic sinusoids.17,20

Pulmonary venous obstruction dictates the clinical presentation and physiology.17 Patients without pulmonary venous obstruction generally present with symptoms later in the newborn period or in infancy or childhood.18,20 Symptoms can be nonspecific and include tachypnea, feeding difficulties, repeated respiratory infections, and failure to thrive.10 The anomalous venous connection acts as a large left-to-right shunt with a marked increase in pulmonary blood flow, especially after the pulmonary vascular resistance drops normally after birth. All patients with TAPVC have either a patent foramen ovale or an ASD. The atrial connection can be small and can contribute to venous obstruction. When pulmonary venous flow is obstructed, pulmonary blood flow is limited, leading to pulmonary venous hypertension and congestion. Because the amount of blood flowing through the pulmonary circuit is not increased, inadequate oxygenation occurs. Patients with this disorder typically present in the neonatal period, often shortly after birth, with marked cyanosis, and cardiorespiratory failure.

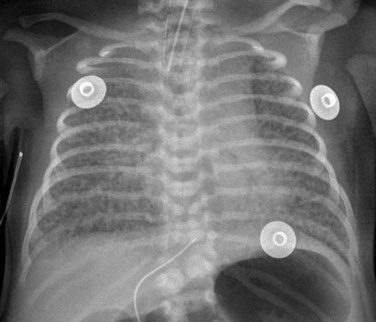

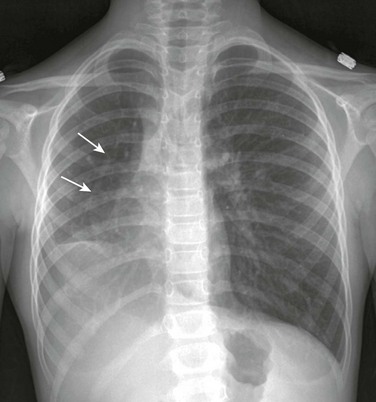

Imaging: Chest radiograph findings in persons with TAPVC without obstruction include increased pulmonary vascularity because of the marked left-to-right shunt, along with main pulmonary artery and right heart enlargement. Occasionally, the anomalous course of a pulmonary vein or the vertical course of a dilated left vertical vein may be seen (Fig. 72-9). In patients with obstructed pulmonary venous flow, the chest radiograph shows pulmonary venous congestion, and because of the decreased inflow to the left heart, the heart often is not enlarged (Fig. 72-10). Cross-sectional imaging goals are listed in the PAPVC imaging section.

Treatment: Patients with obstructed TAPVC and unstable hemodynamics must undergo urgent repair because no effective medical management options are available. Timing of repair for patients without venous obstruction can be more elective. The surgical objective is to redirect pulmonary venous flow to the left atrium, remove the anomalous connection or connections, and close the ASD. Long-term outcome is excellent after repair, with 5-year survival rates of up to 97%.21 The major postoperative complication is persistent or progressive pulmonary venous obstruction in 15% to 19% of patients.18,20

Cor Triatriatum and Other Anomalies of the Pulmonary Veins

Overview: Cor triatriatum sinister or “divided left atrium” is rare, representing only 0.1% to 0.4% of congenital heart disease cases.22,23 It is associated with other cardiac anomalies in 12% to 50% of cases.24

Etiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Presentation: In cor triatriatum, the pulmonary veins connect to an accessory left atrial chamber, which is separated from the true left atrium by a fibromuscular membrane with a typically small, obstructed opening (e-Fig. 72-11).23 An ASD may be present. The embryology is thought to result from incomplete incorporation of the common pulmonary vein into the left atrium, and the accessory chamber represents the embryologic common pulmonary vein.25 Localized stenosis, hypoplasia, or atresia of individual or all pulmonary veins also can occur, with abnormal absorption of the common pulmonary vein into the left atrium.26 With these variants, an accessory left atrial chamber does not exist, but there is either focal stenosis of pulmonary veins near the left atrial junction, diffuse long-segment hypoplasia or narrowing of individual pulmonary veins, or unilateral or bilateral atresia of the common pulmonary vein or of individual pulmonary veins in extreme cases.27

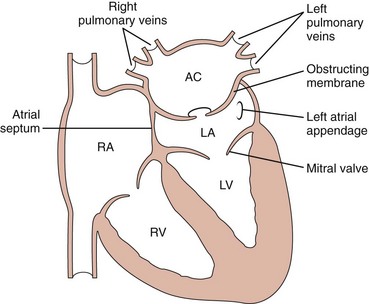

e-Figure 72-11 Diagram of cor triatriatum.

An accessory chamber (AC) of the left atrium (LA) is present, with an obstructing membrane in between. Note that the mitral valve and the left atrial appendage are part of the true left atrium. LV, Left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

Because of the typically obstructed opening between the accessory left atrium and the true left atrium, the predominant physiology is that of pulmonary venous obstruction. With very small openings and more severe obstruction, patients tend to present in the neonatal period with low cardiac output and right heart failure.28 With larger, less obstructed openings, patients may not present with symptoms until older childhood or even adulthood. The pathophysiology of individual or total pulmonary vein hypoplasia, stenosis, or atresia is similar to that of cor triatriatum. Complete atresia of all the individual pulmonary veins is not compatible with life unless significant bronchopulmonary venous collaterals are present (e-Fig. 72-12).29

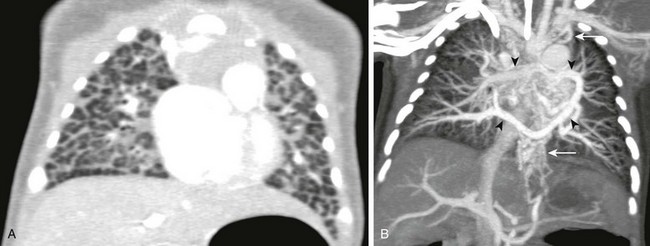

e-Figure 72-12 Newborn with total anomalous pulmonary venous connection and pulmonary vein atresia.

A, Coronal computed tomography (CT) lung window shows severe interstitial edema and septal thickening. B, A coronal CT maximum intensity projection image shows that the anomalous pulmonary veins (arrowheads) join but the common pulmonary vein is atretic, and thus the venous drainage is via multiple small collateral vessels to the systemic system (arrows).

Imaging: The chest radiograph may show evidence of right ventricular enlargement and pulmonary edema related to the pulmonary venous obstruction. Enlargement of the left atrial region, representing both left atrial chambers, also may be present.

Cross-sectional imaging goals include evaluation of the two left atrial chambers and the intervening membrane and complete evaluation of the pulmonary vein and the relationship of the veins to the membrane (Fig. 72-13). CT is ideal for evaluation of pulmonary vein stenosis and for evaluation of the lung.30,31

Figure 72-13 Magnetic resonance imaging of cor triatriatum.

A, Four-chamber steady-state free-precession image showing a linear membrane in the left atrium (arrow) proximal to the mitral valve. B, Cine gradient echo showing dephasing (arrow) distal to the membrane indicating obstruction of pulmonary venous blood flow. LA, Left atrium; LV, left ventricle. (Courtesy Rajesh Krishnamurthy, Texas Children’s Hospital, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas.)

Treatment: Surgery for cor triatriatum is generally performed as soon as the diagnosis is made. The intervening septum of the left atrium is resected and if an ASD is present, it is closed. The prognosis is good for patients who survive the perioperative period and who have no associated cardiac anomalies.28 Operative management of individual pulmonary vein hypoplasia, stenosis, or atresia is variable. The prognosis is not as favorable, and balloon angioplasty has led to disappointing results.32,33 Atresia of the common pulmonary vein with a sizable pulmonary venous confluence may be repaired, similar to TAPVC.34,35

Anomalies of Systemic Venous Connections

Anomalies of the Superior Vena Cava

Persistence of the left SVC results from failure of the left anterior and left common cardinal veins to involute.36 In patients with congenital heart disease, the incidence varies from 11% to 34%.37,38 Bilateral SVCs usually have normal drainage, with the right SVC into the right atrium and the left SVC to the coronary sinus and the right atrium (92%); however, abnormal drainage to the left atrium via an unroofed coronary sinus occurs in 8% of cases (e-Fig. 72-14).39 Although bilateral SVCs with normal drainage have no hemodynamic consequences, technical implications can be present during cardiac catheterization or surgery. Abnormal SVC drainage into the left atrium can result in cyanosis. A left SVC may be suspected based on a shadow in the left upper border of the mediastinum on a chest radiograph. Imaging will show an associated dilated coronary sinus, and the caliber of the brachiocephalic vein is inversely proportional to the size of the left SVC (Fig. 72-15).

Figure 72-15 Magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) of left superior vena cava (SVC).

A coronal thick maximum intensity projection MRA showing bilateral SVCs (asterisks). A small bridging vein is present (arrowhead).

e-Figure 72-14 A chest radiograph with left superior vena cava (SVC).

A frontal chest radiograph in a newborn showing a left-sided central venous catheter extending into the left SVC (white arrow), the coronary sinus, and through the right atrium with its tip in the inferior vena cava, hepatic vein, or ductus venosus (black arrow). An umbilical venous catheter also is shown (arrowhead).

Anomalies of the Inferior Vena Cava and Hepatic Veins

IVC anomalies include interrupted IVC, which is defined by the absence of the hepatic or infrahepatic segment of the IVC with azygous or hemiazygous continuation into the right or left SVC (e-Fig. 72-16)40 and is seen in up to 86% of patients with visceral heterotaxy and polysplenia.41 Patients with asplenia usually have normal IVC but can have a prominent azygous vein and separate drainage of the hepatic veins into the right atrium (e-Fig. 72-17).42,43

e-Figure 72-16 Interrupted inferior vena cava (IVC) with azygous continuation.

Posterior view three-dimensional magnetic resonance angiogram showing interrupted IVC (arrow) with azygous continuation coursing posterior to the liver, draining into the left superior vena cava (asterisk).

e-Figure 72-17 Systemic venous abnormality in heterotaxy.

A three-dimensional magnetic resonance angiogram posterior view showing abnormal hepatic venous drainage with the right-sided hepatic veins (arrow) draining directly to the right-sided atrium and the left-sided hepatic veins (arrowhead) draining to the left-sided atrium. Asterisks mark the atrial septum.

Anomalies of the Brachiocephalic Veins

The normal course of the left brachiocephalic vein is obliquely downward to the right, passing anterior to the aortic arch. A retroaortic brachiocephalic vein is characterized by an abnormal position behind the ascending aorta (e-Fig. 72-18).44 An anomalous retroesophageal brachiocephalic vein is characterized by an abnormal course posterior to the trachea and esophagus and joining the azygous vein before draining to the SVC (e-Fig. 72-19).45

e-Figure 72-18 Retroaortic left brachiocephalic vein.

A, A three-dimensional magnetic resonance angiogram showing the left brachiocephalic vein (asterisk) coursing posterior and inferior to the aortic arch (Ao) draining to the superior vena cava (arrow). (Courtesy Rajesh Krishnamurthy, Texas Children’s Hospital, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas.)

e-Figure 72-19 Retrotracheal and retroesophageal left brachiocephalic vein.

A three-dimensional computed tomography angiography posterior view showing the retroaortic and retrotracheal left brachiocephalic vein (arrowheads). The esophagus is collapsed and not seen. An anomalous right pulmonary arterial to venous communication is present.

Dillman, JR, Yarram, SG, Hernandez, RJ. Imaging of pulmonary venous developmental anomalies. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192(5):1272–1285.

Kafka, H, Mohiaddin, RH. Cardiac MRI and pulmonary MR angiography of sinus venosus defect and partial anomalous pulmonary venous connection in cause of right undiagnosed ventricular enlargement. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192(1):259–266.

Martinez-Jimenez, S, Heyneman, LE, McAdams, HP, et al. Nonsurgical extracardiac vascular shunts in the thorax: clinical and imaging characteristics. Radiographics. 2010;30(5):e41.

References

1. Brody, H. Drainage of the pulmonary veins into the right side of the heart. Arch Pathol. 1942;33:221–240.

2. Healey, JE, Jr. An anatomic survey of anomalous pulmonary veins: their clinical significance. J Thorac Surg. 1952;23(5):433–444.

3. Van Meter, C, Jr., LeBlanc, JG, Culpepper, WS, 3rd., et al. Partial anomalous pulmonary venous return. Circulation. 1990;82(5 suppl):IV195–IV198.

4. Alsoufi, B, Cai, S, Van Arsdell, GS, et al. Outcomes after surgical treatment of children with partial anomalous pulmonary venous connection. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84(6):2020–2026.

5. Chassinat, R. Observation d’anomalies anatomiques remarquables d l’appariel circulatoire. Arch Gen Med. 1836;11:80–91.

6. Cooper, G. Case of malformation of thoracic viscera. London Med Gaz. 1836;18:600–602.

7. Gao, YA, Burrows, PE, Benson, LN, et al. Scimitar syndrome in infancy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22(3):873–882.

8. Midyat, L, Demir, E, Askin, M, et al. Eponym. Scimitar syndrome. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;169(10):1171–1177.

9. Kafka, H, Mohiaddin, RH. Cardiac MRI and pulmonary MR angiography of sinus venosus defect and partial anomalous pulmonary venous connection in cause of right undiagnosed ventricular enlargement. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192(1):259–266.

10. Geva, T, Van Praagh, S, Anomalies of the pulmonary veins. Moss and Adams’ heart disease in infants, children, and adolescents: including the fetus and young adult, 7th ed. Moss, A, Allen, H, eds. Moss and Adams’ heart disease in infants, children, and adolescents: including the fetus and young adult, Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008;vol 2.

11. Dupuis, C, Charaf, LA, Breviere, GM, et al. The “adult” form of the scimitar syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 1992;70(4):502–507.

12. Oh, KH, Choo, KS, Lim, SJ, et al. Multidetector CT evaluation of total anomalous pulmonary venous connections: comparison with echocardiography. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39(9):950–954.

13. Valsangiacomo, ER, Levasseur, S, McCrindle, BW, et al. Contrast-enhanced MR angiography of pulmonary venous abnormalities in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2003;33(2):92–98.

14. Ou, P, Marini, D, Celermajer, DS, et al. Non-invasive assessment of congenital pulmonary vein stenosis in children using cardiac-non-gated CT with 64-slice technology. Eur J Radiol. 2009;70(3):595–599.

15. Grosse-Wortmann, L, Al-Otay, A, Goo, HW, et al. Anatomical and functional evaluation of pulmonary veins in children by magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(9):993–1002.

16. Backer, CL, Mavroudis, C. Atrial septal defect, partial anomalous pulmonary venous connection, and scimitar syndrome. In Mavroudis C, Backer CL, eds.: Pediatric cardiac surgery, 3rd ed, Philadelphia: Mosby, 2003.

17. Herlong, J, Jaggers, J, Ungerleider, R. Congenital Heart Surgery Nomenclature and Database Project: pulmonary venous anomalies. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;69(4 suppl):S56–S69.

18. Kelle, A, Backer, C, Gossett, J, et al. Total anomalous pulmonary venous connection: results of surgical repair of 100 patients at a single institution. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139(6):1387–1394.

19. Lucas RV Jr, Adams, P, Jr., Anderson, RC, et al. Total anomalous pulmonary venous connection to the portal venous system: a cause of pulmonary venous obstruction. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1961;86:561–575.

20. Seale, AN, Uemura, H, Webber, SA, et al. Total anomalous pulmonary venous connection: morphology and outcome from an international population-based study. Circulation. 2010;122(25):2718–2726.

21. Karamlou, T, Gurofsky, R, Al Sukhni, E, et al. Factors associated with mortality and reoperation in 377 children with total anomalous pulmonary venous connection. Circulation. 2007;115(12):1591–1598.

22. Jorgensen, CR, Ferlic, RM, Varco, RL, et al. Cor triatriatum. Review of the surgical aspects with a follow-up report on the first patient successfully treated with surgery. Circulation. 1967;36(1):101–107.

23. Niwayama, G. Cor triatriatum. Am Heart J. 1960;59:291–317.

24. Brown, JW, Hanish, SI. Cor triatriatum sinister, atresia of the common pulmonary vein, pulmonary vein stenosis, and cor triatriatum dexter. In Mavroudis C, Backer CL, eds.: Pediatric cardiac surgery, 3rd ed, Philadelphia: Mosby, 2003.

25. Parsons, CG. Cor triatriatum; concerning the nature of an anomalous septum in the left auricle. Br Heart J. 1950;12(4):327–338.

26. Reye, RD. Congenital stenosis of the pulmonary veins in their extrapulmonary course. Med J Aust. 1951;1(22):801–802.

27. Shone, JD, Amplatz, K, Anderson, RC, et al. Congenital stenosis of individual pulmonary veins. Circulation. 1962;26:574–581.

28. van Son, JA, Danielson, GK, Schaff, HV, et al. Cor triatriatum: diagnosis, operative approach, and late results. Mayo Clin Proc. 1993;68(9):854–859.

29. Deshpande, JR, Kinare, SG. Atresia of the common pulmonary vein. Int J Cardiol. 1991;30(2):221–226.

30. Gahide, G, Barde, S, Francis-Sicre, N. Cor triatriatum sinister: a comprehensive anatomical study on computed tomography scan. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(5):487.

31. Saremi, F, Gurudevan, SV, Narula, J, et al. Multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) in diagnosis of “cor triatriatum sinister. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2007;1(3):172–174.

32. Driscoll, DJ, Hesslein, PS, Mullins, CE. Congenital stenosis of individual pulmonary veins: clinical spectrum and unsuccessful treatment by transvenous balloon dilation. Am J Cardiol. 1982;49(7):1767–1772.

33. Mendelsohn, AM, Bove, EL, Lupinetti, FM, et al. Intraoperative and percutaneous stenting of congenital pulmonary artery and vein stenosis. Circulation. 1993;88(5 pt 2):II210–II217.

34. Shimazaki, Y, Yagihara, T, Nakada, T, et al. Common pulmonary vein atresia: a successfully corrected case. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 1987;28(4):395–397.

35. Suzuki, T, Sato, M, Murai, T, et al. Successful surgical repair of common pulmonary vein atresia in a newborn. Pediatr Cardiol. 2001;22(3):255–257.

36. Sanders, JM. Bilateral superior vena cavae. Anat Rec. 1946;94:657–662.

37. Nsah, EN, Moore, GW, Hutchins, GM. Pathogenesis of persistent left superior vena cava with a coronary sinus connection. Pediatr Pathol. 1991;11(2):261–269.

38. Van Praagh, S, O’Sullivan, J, Brili, S, et al. Juxtaposition of the morphologically right atrial appendage in solitus and inversus atria: a study of 35 postmortem cases. Am Heart J. 1996;132(2 pt 1):382–390.

39. Meadows, WR, Sharp, JT. Persistent left superior vena cava draining into the left atrium without arterial oxygen unsaturation. Am J Cardiol. 1965;16:273–279.

40. Walters, HL. Anomalous systemic venous connections. In Mavroudis C, Backer CL, eds.: Pediatric cardiac surgery, 3rd ed, Philadelphia: Mosby, 2003.

41. Bengur, AR, Jaggers, J, Ungerleider, RM. Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography in congenital heart disease. In Mavroudis C, Backer CL, eds.: Pediatric cardiac surgery, 3rd ed, Philadelphia: Mosby, 2003.

42. Geva, T, Van Praagh, S, Abnormal systemic venous connections. Moss and Adams’ heart disease in infants, children, and adolescents: Including the fetus and young adult, 7th ed. Moss, A, Allen, H, eds. Moss and Adams’ heart disease in infants, children, and adolescents: Including the fetus and young adult, Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008;vol 2.

43. Rubino, M, Van Praagh, S, Kadoba, K, et al. Systemic and pulmonary venous connections in visceral heterotaxy with asplenia. Diagnostic and surgical considerations based on seventy-two autopsied cases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;110(3):641–650.

44. Choi, JY, Jung, MJ, Kim, YH, et al. Anomalous subaortic position of the brachiocephalic vein (innominate vein): an echocardiographic study. Br Heart J. 1990;64(6):385–387.

45. Ming, Z, Aimin, S, Rui, H. Evaluation of the anomalous retroesophageal left brachiocephalic vein in Chinese children using multidetector CT. Pediatr Radiol. 2009;39(4):343–347.