Chapter 2 ABNORMAL HEAD SIZE AND SHAPE

General Discussion

What constitutes a normal head size is based on statistical renderings of morphology. Abnormalities detected more easily by routine screening, measurement, and plotting on graphs that are widely available. Accurate measurement of the occiputofrontal circumference (OFC) is crucial in this regard. Abnormal head or face shapes may vary from the very subtle to the dramatic. Without direct familiarity of the more common syndromes that cause these abnormalities, a health care provider might detect that some abnormality exists without being able to articulate or pinpoint exactly what is outside the norm. Morphologic nomenclature is outlined in Table 2-1.

| Term | Meaning | Suture Involved |

|---|---|---|

| Dolichocephaly | Long head | Sagittal suture |

| Scaphocephaly | Keel-shaped head | Sagittal suture |

| Acrocephaly | Pointed head | Coronal, lambdoid, or all sutures |

| Brachycephaly | Short head | Coronal suture |

| Oxycephaly | Tower-shaped head | Coronal, lamboid, or all sutures |

| Turricephaly | Tower-shaped head | Coronal suture |

| Trigonocephaly | Triangular-shaped head | Metopic suture |

| Plagiocephaly | Asymmetric head | Unilateral lambdoid or positional |

| Kleeblattschadel | Cloverleaf skull | Multiple but not all sutures |

| Craniofacial dysostosis | Midface deficiency | Craniosynostosis with involvement of cranial base sutures |

(From Mooney PM, Siegel MI. Understanding Craniofacial Anomalies. New York: Wiley-Liss, 2002:12, with permission.)

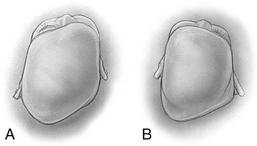

It is important to differentiate lambdoid synostosis from deformational plagiocephaly, which results from local pressure on a specific region of the skull, typically in one occipital region. The number of infants with deformational plagiocephaly has increased, partly as a result of the “Back to Sleep” campaign. The diagnosis of deformational plagiocephaly can be made clinically by viewing the infant’s head from the top. The differences between deformational plagiocephaly and craniosynostosis are outlined in Figure 2-1. The diagnosis of deformational plagiocephaly is made when the deformations noted in Figure 2-2 are present in an infant who had a typically round head at birth but, a few weeks or months later, the parents notice deformation of head shape.

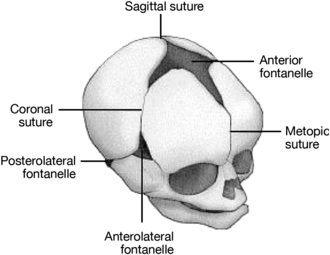

Figure 2-1 Major cranial sutures and fontanelles.

(From Texas Pediatric Surgical Associates, Houston, Texas, with permission.)

Figure 2-2 Differences between positional plagiocephaly (A) and unilamdoid synostosis (B).

(From Gruss JS, Ellenbogen RG, Whelan MF. Lambdoid synostosis and posterior plagiocephaly. In: Lin KY, Ogle RC, Jane JA, eds. Craniofacial Surgery: Science and Surgical Technique. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002:242.)

Causes of Abnormal Head Size and Shape

• Normal variant (by definition 5%) or familial

• Abnormal brain development or delay

• TORCH (toxoplasmosis, other infections, rubella, cytomegalovirus infection, and herpes simplex virus) exposure

• Normal variant (by definition 5%) or familial

• Brain mass (benign or malignant)

Key Historical Features

Key Physical Findings

Accurate measurement of the occipitofrontal circumference

Accurate measurement of the occipitofrontal circumference

Funduscopic examination for papilledema

Funduscopic examination for papilledema

Abnormal positioning of the ears

Abnormal positioning of the ears

Asymmetry or other abnormalities of facies

Asymmetry or other abnormalities of facies

Flattened occiput and ipsilateral bulging frontal skull (suggesting possible plagiocephaly)

Flattened occiput and ipsilateral bulging frontal skull (suggesting possible plagiocephaly)

Abnormal weight loss or deceleration of growth

Abnormal weight loss or deceleration of growth

Neurologic examination for hypotonia

Neurologic examination for hypotonia

Other evidence of syndromic dysmorphisms

Other evidence of syndromic dysmorphisms

Palpable suture ridge (with abnormal head size)

Palpable suture ridge (with abnormal head size)

Premature or late closure of anterior fontanelle (with abnormal head size)

Premature or late closure of anterior fontanelle (with abnormal head size)

Suggested Work-up

| Concise plotting of growth curves | For screening purposes and to determine whether microcephaly or macrocephaly is present |

| Measurement of parents and siblings | To determine whether head size variation is familial |

| Skull radiographs (anteroposterior and lateral views of the skull) or computed tomography (CT) | To evaluate the sutures in cases of suspected craniosynostosis. The sutures can be identified more accurately on a CT scan, and CT scanning helps in evaluating the brain for structural abnormalities and in excluding other causes of asymmetric vault growth |

| Pediatric neurosurgery consultation | Usually indicated in cases of macrocephaly or head deformity |

| Pediatric neurology or genetics consultation | Usually indicated for cases of microcephaly without skull deformity |

Additional Work-up

| Ultrasonography | Can be used to evaluate for ventricular dilatation if the anterior fontanelle is open |

| Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) | Preferable if neuroanatomy needs to be visualized well. Can detect cortical and white-matter abnormalities such as degenerative diseases and can document the extent of calvarial masses. |

| Genetic studies, including karyotyping or genetic screening for syndromic phenotypes | If indicated by history and physical examination. Often deferred until genetics consultation is obtained |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) | If hyperthyroidism is suspected |

| Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine | If renal failure is suspected (linked to rickets and craniosynostosis) |

| Vitamin D level | If rickets is suspected (linked to craniosynostosis) |

1. Delashaw J., Persing J., Jane J. Cranial deformation in craniosynostosis: a new explanation. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1991;2:611–620.

2. Dufresne C., Carson B., Zinreich S. Complex Craniofacial Problems. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1992. 160

3. Gruss J.S., Ellenbogen R.G., Whelan M.F. Lambdoid synostosis and posterior plagiocephaly. In: Lin K.Y., Ogle R.C., Jane J.A., editors. Craniofacial Surgery: Science and Surgical Technique. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002:233–351.

4. Hoyte D. The cranial base in normal and abnormal skull growth. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1991;2:515–537.

5. Kiesler J., Ricer R. The abnormal fontanel. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:2547–2552.

6. Mooney M.P., Siegel M.I. Understanding Craniofacial Anomalies. New York: Wiley-Liss; 2002. 4

7. Piatt J.H.Jr. Recognizing neurosurgical conditions in the pediatrician’s office. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2004;51(2):237–270.

8. Ridgway E.B., Weiner H.L. Skull deformities. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2004;51(2):359–387.