CHAPTER 66 Abdominoplasty techniques

Physical evaluation

• Listening attentively to the complaint and sensing the level of expectation of the patients, the majority female, normally provides a reasonable degree of information regarding the extent of the surgery, its implications and consequences.

• It is important to warn about the existence, location and size of the scars during the physical exam. In order to be more objective, it is helpful to draw the supposed scars on the patient’s abdomen.

• The patient should be examined in a standing position with abdomen exposed. The seated exam should be added when such would provide greater clarity. In this position, the patient has difficulty in contracting the abdominal musculature, which facilitates real knowledge of the shape of the abdomen, showing the situation in its fullest degree.

• After the exam, all the implications of an abdominoplasty are discussed exhaustively: age, fertility, time necessary for recovery, return to his/her normal activities, period of internment, type of anesthetics, dressings, drains, as well as risks arising from the surgery.

• The most frequent complication must be pointed out, namely deep vein thrombosis in the lower limbs, and factors that predispose the patient to this incident should be discussed. It is also opportune, although it may seem premature, to instruct the patient about what measures are necessary for prophylaxis of the DVT.

• It is important to associate an abdominal ultrasonography to the basic exams, so as to detect any pathology that could contraindicate the surgery.

• Women of child-bearing age should be warned that abdominal stretch with future pregnancies would interfere with the quality of the result.

• In secondary abdomens with the presence of marked irregularities and supposition of hernia, it is also appropriate to use magnetic resonance.

• In abdomens with large distension or voluminous incisional hernias, the wearing of a girdle for abdominal containment for around a month prior to surgery is fundamental. Thus, a gradual adaptation will occur after surgical adjustment of the abdominal wall, as the consequent elevation of the diaphragm could entail respiratory dysfunction in the postoperative period.

• It is of great importance to know all the medication normally used, emphasizing the need to suspend those substances that could interfere with coagulation two or three weeks before surgery.

• Smokers represent a serious potential for the flap to incur damage. Even those who affirm that they have given up smoking in time (minimum one month prior to surgery) are considered smokers, requiring the care inherent to this type of situation.

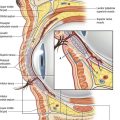

Anatomy of the abdominal wall

Innervation

The anterior abdominal wall is innervated by the intercostal and subcostal nerves T7–T11.

Technical steps

Variants of the block abdominoplasties

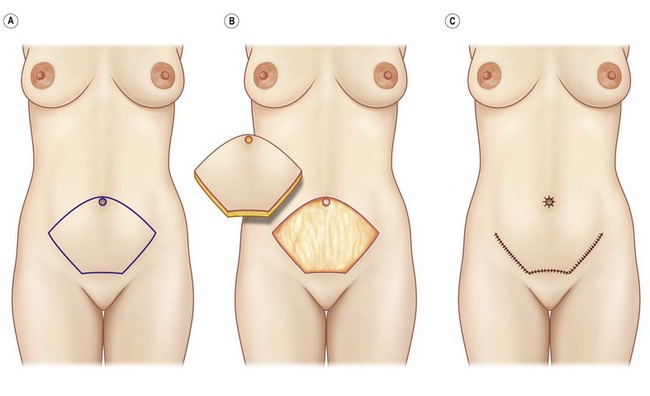

The variants, well-clarified in the respective illustrations, are:

• Type I: Cranial marking of the ellipse glancing across the upper edge of the umbilical scar.

• Type II: Mini – same marking occupying approximately the lower third between the umbilicus and the pubis.

• Type III: Half way between the umbilicus and the pubis, with disinsertion below the umbilical scar.

• Type IV: Generally in secondary abdomen. The flap descends with closure of the original place of the umbilicus.

Other applications are: vertical, high horizontal abdomen and thigh lifting.

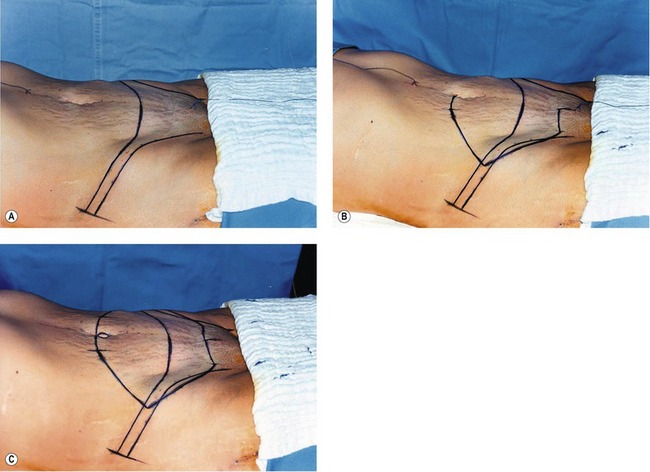

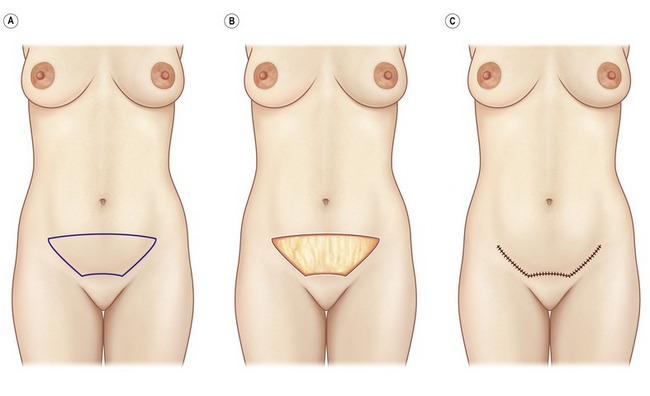

Irrespective of the variant indicated, prior marking with the bikini is fundamental, the patient standing, preferably on the eve of surgery. For this maneuver, the patient must wear a bikini with broad side straps in the position that they will be worn in the future (Fig. 66.1). This marking will ensure perfect symmetry of the drawing of the intended resection, as well as the future location of the scar, which should be concealable by this type of clothing.

Type I

The two lower lateral arcs must be equally curved, with curvature opposite to that of the upper ones (Fig. 66.2A), so that the consequence will be a slightly curved scar, with upper concavity. The pubic segment must be shorter than the diameter of the pubis, whose resulting scar will accompany the trend towards narrower bikinis (Fig. 66.2B). All of this segment is resected in a single block, which is the basis of the technique (Fig. 66.2C). It is important to stress that in closure sutures with greater tension are lateral, to avoid excessive ascension of the pubis.

Surgical sequence

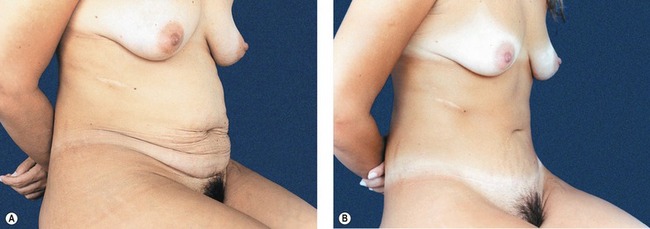

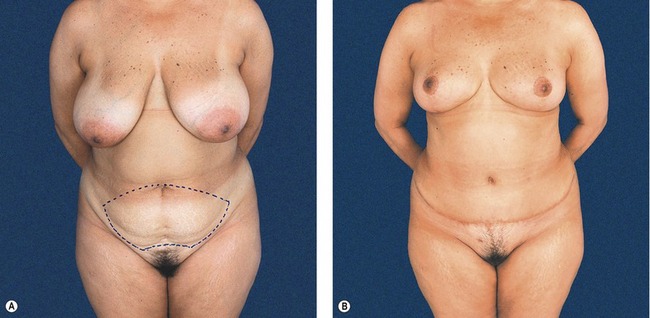

For pre- and postoperative views, please see Fig. 66.3.

Fig. 66.3 A, Preoperative view presenting flaccidity, innumerable strias, abdominal distension which are more evident in this position. This demonstrates the importance of the examination and photographic documentation in the seated position. B, Postoperative phase, in the lighter area. It can be observed that the scar is perfectly concealable by the bikini.

The procedure starts with the patient on the table and demarcation of the bikini (Fig. 66.4A). Beginning with a hemispherical marking, the lateral angle lies within the projection of the bikini, the lower lateral curved line meeting the upper, and the marking of the pubis, shorter than the anatomical limit (Fig. 66.4B). We transfer the demarcation from one side to the other, checking with compasses to ensure the correct measurements.

After complete demarcation (Fig. 66.4C), infiltration of the entire flap is performed with a solution of lidocaine 20 mL at 2%, adrenalin 1 ampoule 1 : 1000, ropivacaine 20 mL at 0.75% and physiological serum 500 mL, throughout the whole area to be incised and resected.

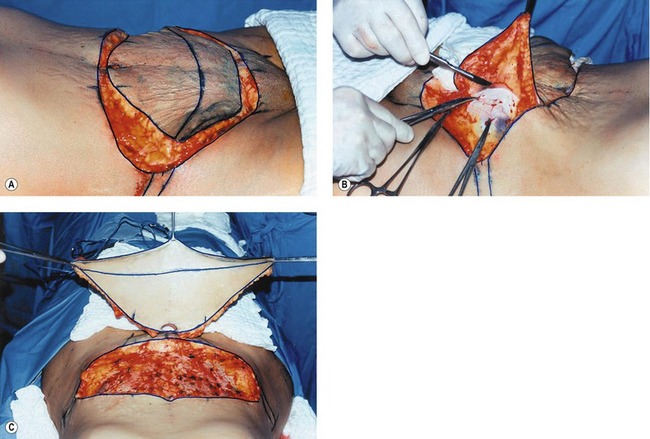

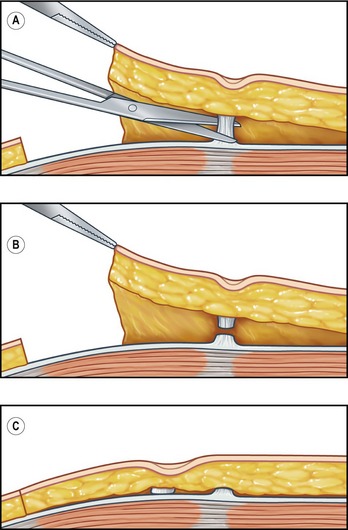

Scoring of the basic points is realized to avoid erasure during the intervention. The surgery starts with incision and freeing of the umbilical markings. Then the flap is totally incised and removed, starting from the lateral angle and extending as far as the medial part (Fig. 66.5A,B). This maneuver, as well as simplifying the surgery, allows prior hemostasis, thereby minimizing the bleeding.

After the flap has been completely excised (Fig. 66.5C), the cranial freeing of the flap starts and progresses to the dissection with cautery as far as the xiphoid process. The amplitude of the undermining, as much in the lateral direction as in the cranial, will depend on the case.

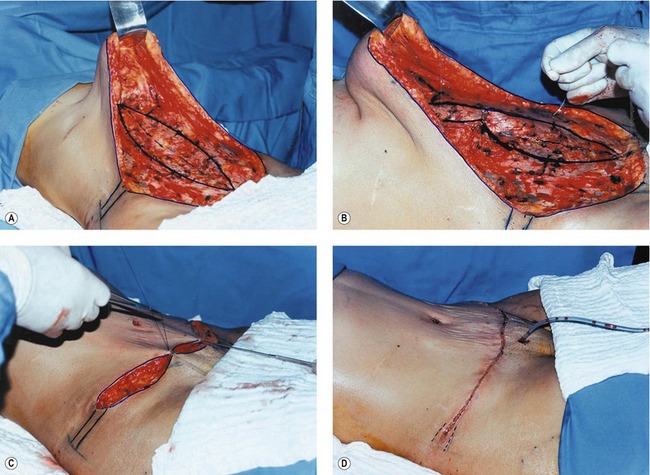

Next in sequence is demarcation of the area to be plicated (Fig. 66.6A), and the plication is conducted with Mersilene 3.0 at separate points (Fig. 66.6B), that must take into account overall readjustment of the abdominal wall and redefinition of the waist.

Assembly starts by gathering the marked points (Fig. 66.6C). Then sutures are placed in the umbilical stump. The surgery ends with active drainage (Fig. 66.6D), and in the use of prophylaxis for DVT with heparin of low molecular weight.

Fig. 66.C1 Clinical case 1. A&B, Patient seated, pre- and postoperative phase. C&D, Pre- and postoperative profile. E&F, Position in  view.

view.

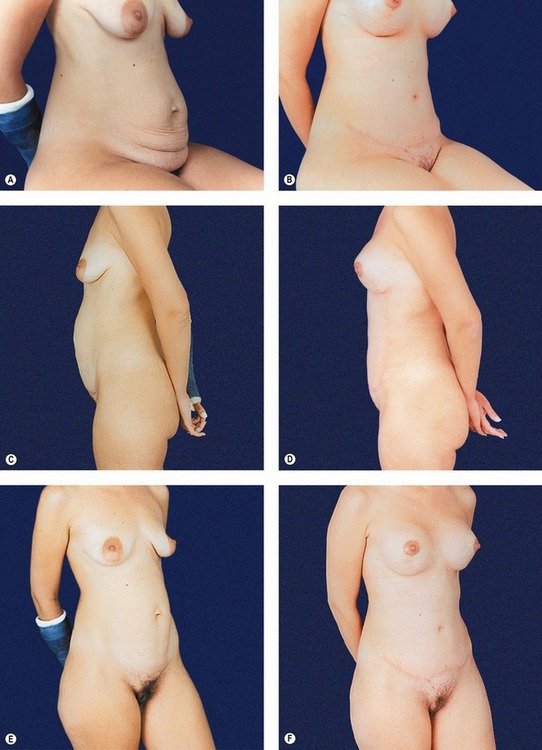

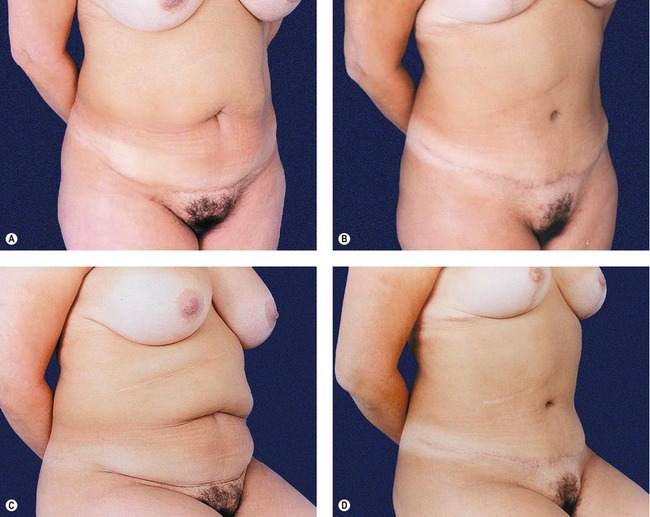

Fig. 66.C2 Clinical case 2. A&B, Patient in  view before and after. Scar following the mark of the bikini. C&D, Patient seated, demonstrating the full definition of all the abdomen as much by the symmetry obtained with the block resection as by the defattening in lamina.

view before and after. Scar following the mark of the bikini. C&D, Patient seated, demonstrating the full definition of all the abdomen as much by the symmetry obtained with the block resection as by the defattening in lamina.

Fig. 66.C3 Clinical case 3. A, Patient with short trunk, adipose tissue, median infra-umbilical scar and mammary hypertrophy. Line interrupted demarcating the type of block resection. B, Postoperative period of the breast and abdomen with defattening. Note that in patients with large redundancy of tissue there is a tendency towards rectification of the scar, departing from the arcing of the original drawing.

Type II

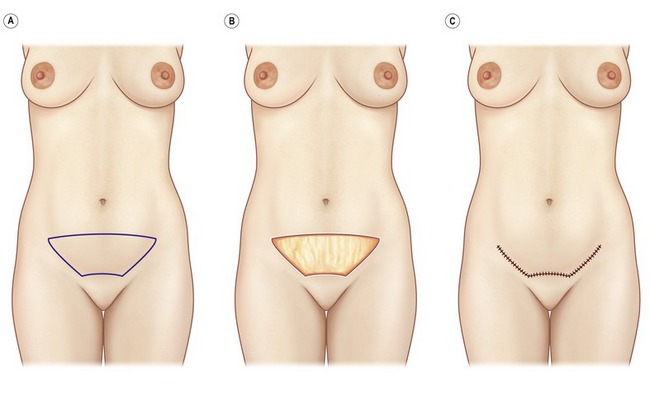

Type II, also denominated mini-abdominoplasty, is a drawing identical to type I, only smaller, in which the marking occupies approximately the lower third between the umbilicus and the pubis (Fig. 66.7A–C), there being a possibility of disinsertion of the umbilicus or not. It is indicated for patients with a high umbilicus and flaccidity isolated above the pubic region. Despite the small dissection, plication of the rectus abdominis muscles may be carried out, which is a slightly laborious hypothesis, due to the difficulty of access to the supra-umbilical region. One must take extreme care with indication of type II (mini-abdominoplasty), given that the temptation of a smaller scar often leads patients to complain of flaccidity in the epigastric region, above all when seated. We have reoperated in some cases, on our own patients or others, to overcome this dissatisfaction. In this case, the indication of type II is extremely wise, whereas it would be denied when there is significant flaccidity in the epigastric region.

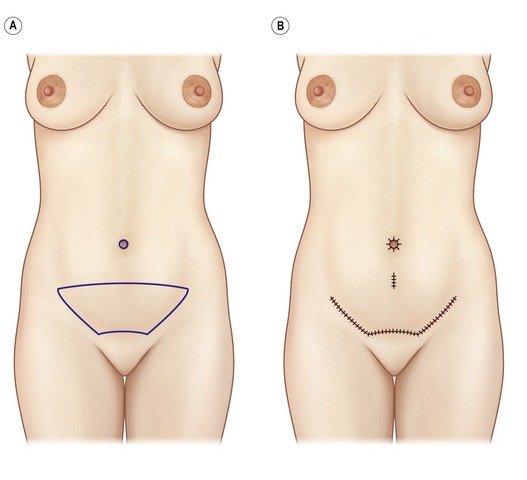

Type III

Variant type III is indicated exclusively in patients with a high umbilicus (Figs 66.8 & 66.9).

Postoperative care

The postoperative care varies according to the type of block resection used. Naturally, general measures are common to all variants. In the cases in which there existed reasonable tension of the flap, it is important that the flexion of the thighs on the trunk adopted on the table, to facilitate the closure of the surgical wound, remain in the transfer and position on the gurney. On the bed, besides maintaining the same position of the legs, lifting of the trunk is added with an inclination that is comfortable for the patient. Throughout the period in bed, active and passive movements of the lower limbs are stimulated for prophylaxis of vein thrombosis. Frequently, and with same purpose, we usually use pneumatic leggings in the first 15–20 postoperative hours.

Using a girdle over the dressing, the patient ambulates on the day immediately after surgery.

Complications

Summary of steps

1. Demarcation of patient wearing a bikini.

2. Infiltration of the entire flap is performed with a solution of lidocaine, adrenalin, and physiological throughout the whole area to be incised and resected.

3. Surgery starts with incision and freeing of the umbilical scar. Then the flap is totally incised and removed, starting from the lateral angle and extending as far as the medial part.

4. After the flap has been completely excised, the cranial freeing of the flap starts and progresses to the dissection with cautery as far as the xiphoid process. The amplitude of the undermining, as much in the lateral direction as in the cranial, will depend on the case.

5. Next in sequence is demarcation of the area to be plicated.

6. This is followed by triangulation and fixing of the umbilical stump to the aponeurosis.

7. Assembly starts by gathering the marked points.

8. Then stitches are placed in the umbilical stump.

9. The surgery ends with active drainage, and in the use of prophylaxis for DVT with heparin of low molecular weight.

10. The above steps apply to the original block abdominoplasty (type I). There are slight variations in technique for the variants type II (mini: lower third between the umbilicus and the pubis.); type III (half way between the umbilicus and the pubis, with disinsertion below the umbilical scar); and type IV (in secondary abdomen; flap descends with closure of the original place of the umbilicus).

Abramo AC, Viola JC, Marques A. The H approach to abdominal muscle aponeurosis for the improvement of body contour. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;86(5):1008–1013.

Abs R. Thromboembolism in plastic surgery: review of the literature and proposal of a prophylaxis algorithm. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2000;45(6):604–609.

Achauer BM, Eriksson E, Guyuron B, Coleman JJ, III., Russell RC, Vander Kolk CA. Abdominoplasty. In: Guyuron B, ed. Plastic surgery: Indications, operations and outcomes. St. Louis: MO: Mosby; 2000:2783–2821.

Akoz T, Akon M, Yilalirim S. If you continue to smoke, we may have a problem: Smoking’s effects on plastic surgery. Aesthet Plastic Surg. 2002;26(6):477–482.

Baroudi R, Ferreira CAA. Seroma: How to avoid it and how to treat it. Aesthet Surg J. 1998;18:439–441.

Cardoso de Castro C, Daher M. Simultaneous reduction mammaplasty and abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1974;61:36.

Floros C, Davis PKB. Complications and long term results following abdominoplasty: A retrospective study. Br J Plast Surg. 1991;44:190–194.

Hester TR, Baird W, Bostwick J, III., et al. Abdominoplasty combined with other major surgical procedures: Safe or sorry? Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;8:997.

Matarasso A. Awareness and avoidance of abdominoplasty complications. Aesthet Plast Surg. 1997;17(4):256–261.

Matarasso A. Minimal-access variations in abdominoplasty. Ann Plast Surg. 1995;34(3):255–263.

Moore KL. Do abdome, Anatomia Orientada para a Clinica, 2nd edn. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Guanabara; 1990.

Nahas FX. Pregnancy after abdominoplasty. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2002;26(4):284–286.

Savage CR. Abdominoplasty combined with other surgical procedures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;70:437.

Sinder R. Cirurgia Plastica do Abdome. Editado pelo autor; 1979.

Tercan M, Bekerecioglu M, Dikensoy O, Kocoglu H. Effects of abdominoplasty on respiratory functions a prospective study. Ann Plast Surg. 2002;49(6):617–620.

Van Uchelen JH, Werker PM, Kon M. Complications of abdominoplasty in 86 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107(7):1869–1873.