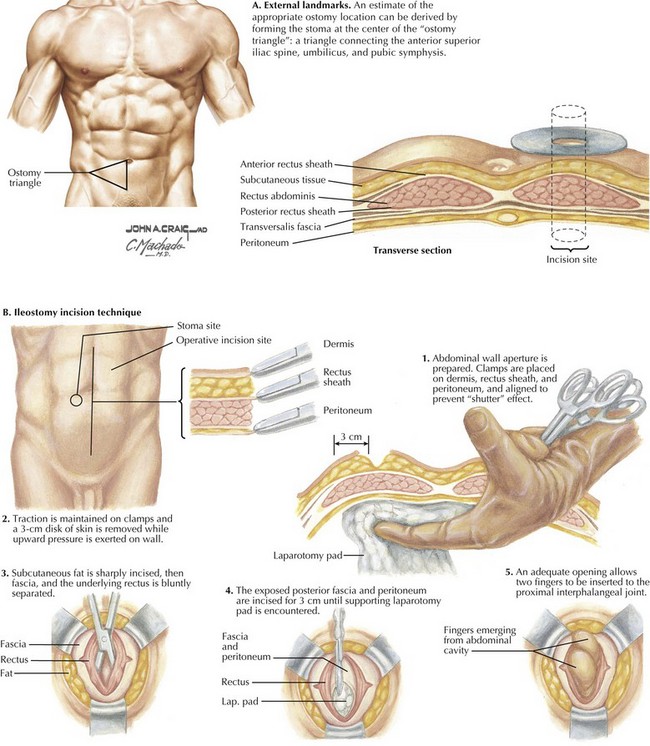

Abdominal Wall Anatomy and Ostomy Sites

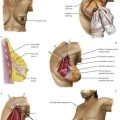

Abdominal Wall Anatomy

The fasciae of the external and internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles converge at the linea semilunaris, lateral to the rectus muscles (Fig. 20-1). Medially, these fasciae converge again at the linea alba. Superior to the linea semicircularis (arcuate line), usually at the umbilicus, the fasciae divide to encircle the rectus muscles completely, forming an anterior and a posterior rectus sheath. Inferior to the linea semicircularis, all layers of the fasciae are anterior to the rectus muscles, with only the transversalis fascia posterior.

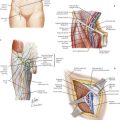

Creating the Trephine

A circle of dermis is excised at the site of the planned ostomy; the subcutaneous tissues are not removed. When a midline incision has been made, the surgeon grasps the converged fasciae at the linea alba with a Kocher forceps through the skin incision. This forceps will be pulled medially to ensure the skin and muscular layers are aligned during creation of the trephine. Using a second Kocher forceps, the surgeon grasps the subcutaneous tissues at the planned ostomy site. A sponge is placed deep to the peritoneum through the incision and pushed anteriorly on the abdominal wall to protect the bowel and minimize the distance between abdominal wall layers (Fig. 20-2, B).

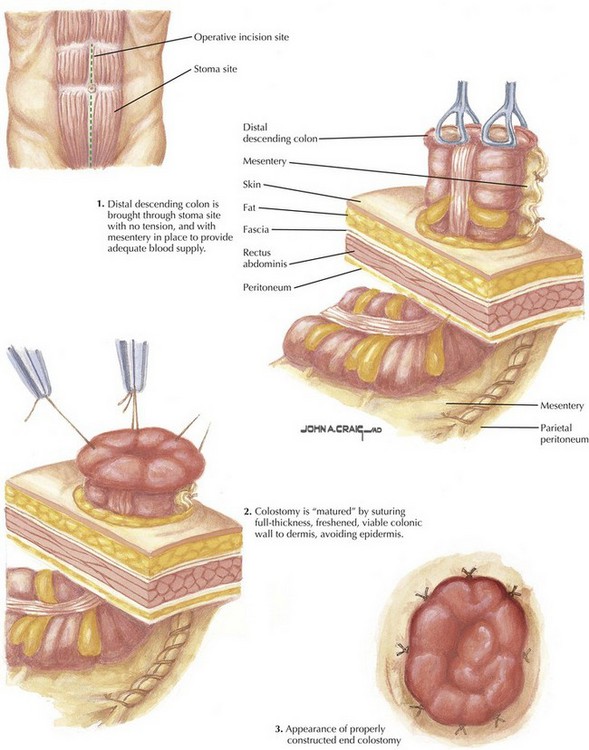

End Ostomy

The distal aspect of the divided small or large intestine is then oriented to ensure the mesentery has no twists or turns. A Babcock clamp is passed through the trephine and the intestine is brought through to the skin. No tension is applied, to prevent inadvertent damage to the intestines or mesentery (Fig. 20-3).

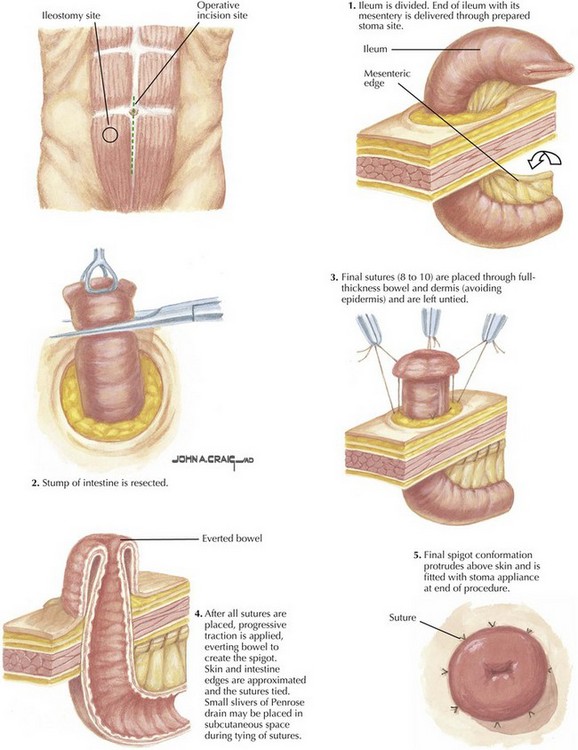

Maturing the Ostomy

Several centimeters of bowel should be brought beyond the skin level. Sutures are placed full thickness from mucosa to serosa at the open end. The suture is then passed subcutaneously at the corresponding site on the trephine, taking care not to pass through the epidermis. Once sutures are placed in four quadrants, the bowel is everted while the sutures are tied (Fig. 20-4).

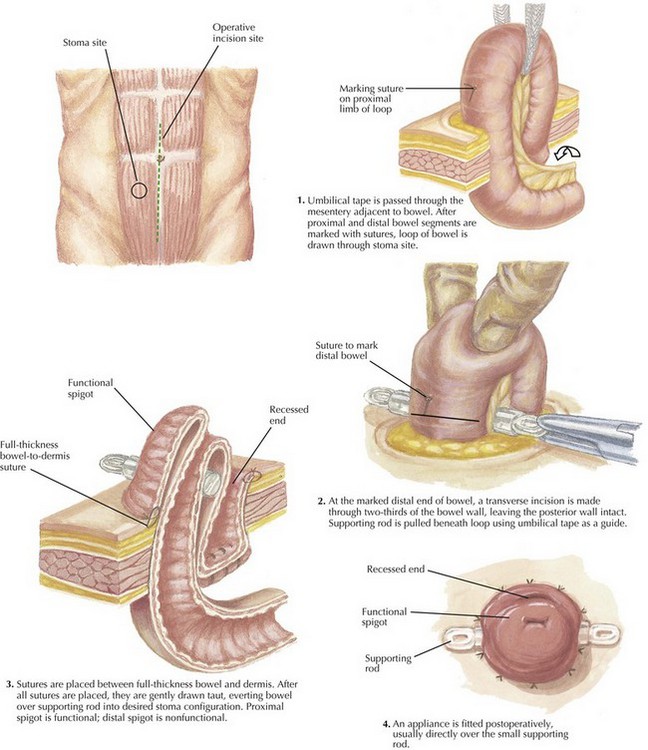

Loop Ostomy

An appropriate segment of bowel is selected for the loop ostomy. Sutures of differing colors can be placed to mark the proximal and distal limbs to ensure correct orientation as the bowel is elevated. A window is created in the mesentery adjacent to the bowel, and umbilical tape is passed through the opening. The ends of the tape are then grasped through the trephine, elevating the ostomy above the skin. The umbilical tape is then exchanged for an ostomy rod (Fig. 20-5, step 1).

Maturing the Ostomy

The distal aspect of the loop is opened transversely across two-thirds its circumference, leaving the posterior wall intact. Distally, absorbable sutures are then placed (Fig. 20-5, step 2), with one in the center and one laterally just inferior to the rod on both sides. Sutures should be full thickness through the bowel and into the dermis, again taking care not to pass through the epidermis.

Sutures are placed proximally, in the same locations. While they are tied, the bowel is everted as a Brooke ileostomy. Brooke ileostomy allow for easier placement of the stoma appliance by elevating the stoma above the level of the epidermis (Fig. 20-5, steps 3 and 4).