20-30% of malignant mesotheliomas arise in peritoneum

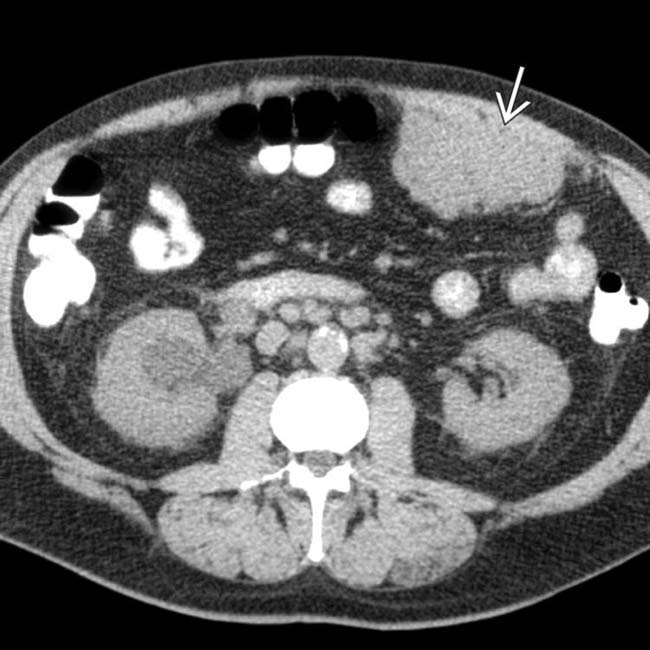

• CT: Omental and peritoneal stranding, nodularity, and discrete masses

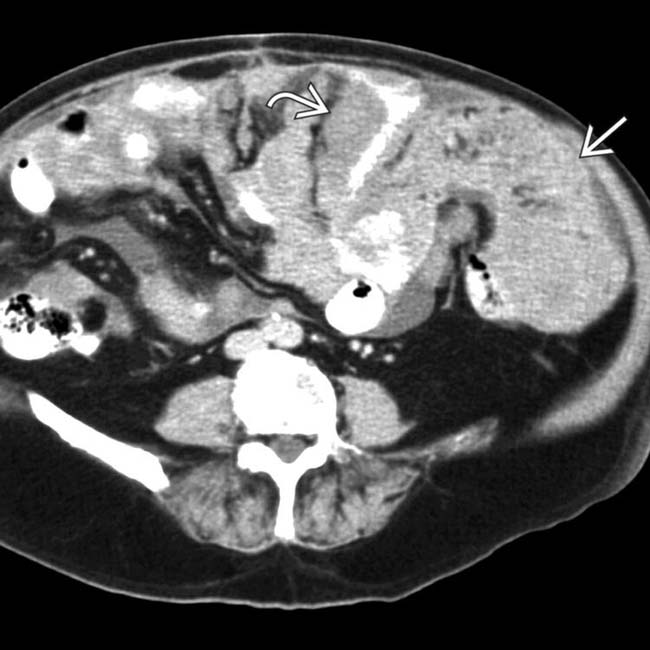

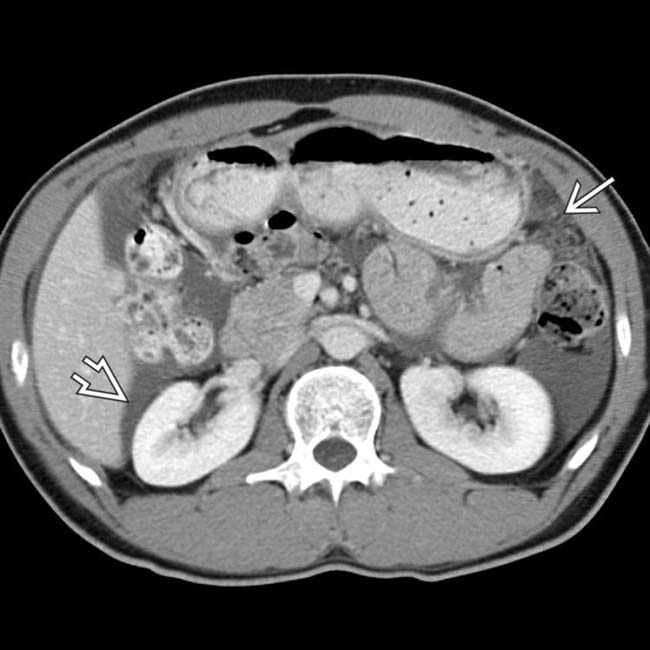

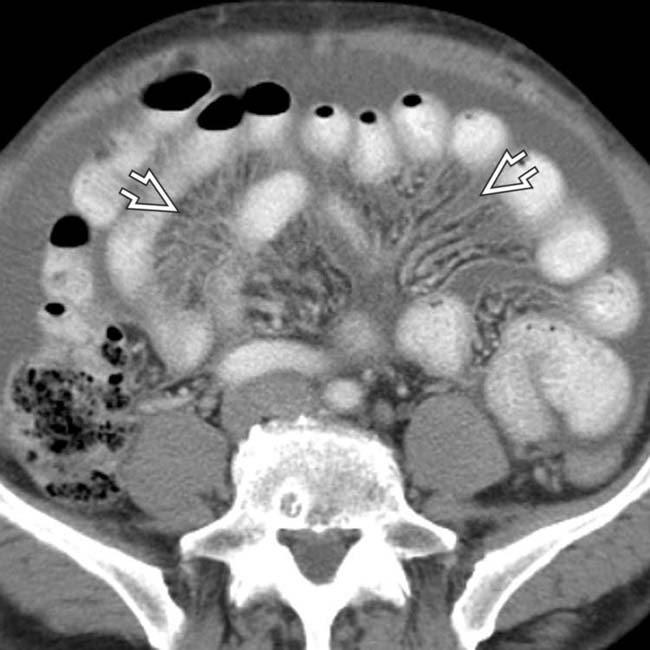

Stellate, thickened (pleated) mesentery secondary to encasement and straightening of mesenteric vessels

Stellate, thickened (pleated) mesentery secondary to encasement and straightening of mesenteric vessels

Stellate, thickened (pleated) mesentery secondary to encasement and straightening of mesenteric vessels

Stellate, thickened (pleated) mesentery secondary to encasement and straightening of mesenteric vessels• MR: Low to intermediate T1WI and intermediate to high T2WI signal intensity of omental and peritoneal masses

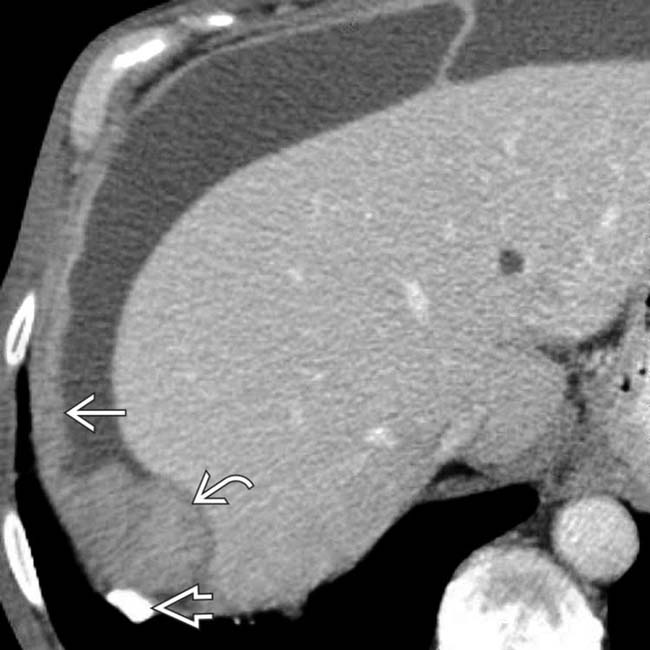

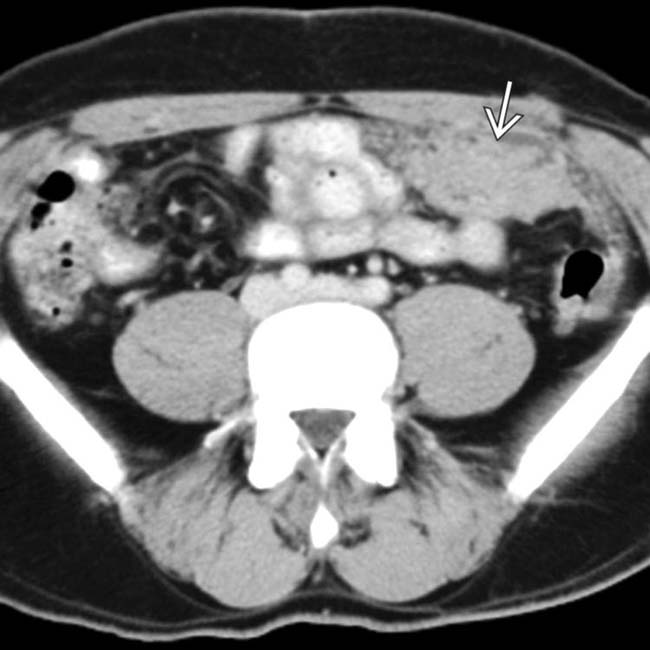

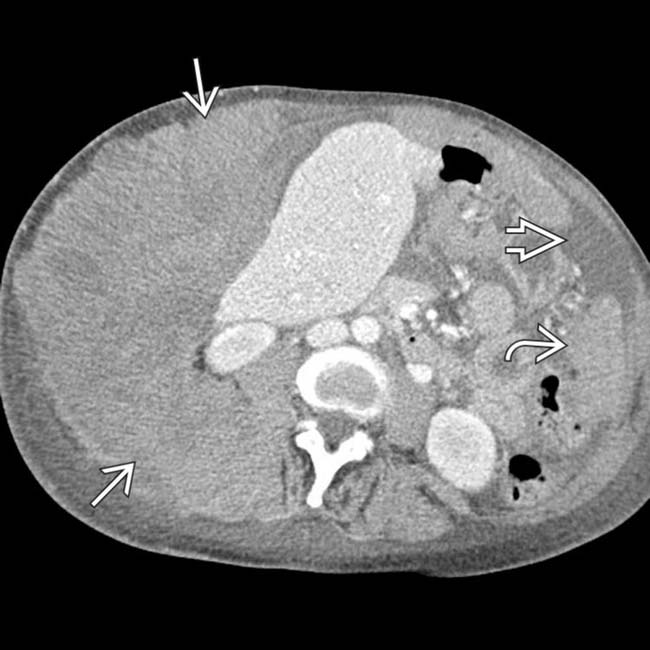

. The parietal peritoneum under the diaphragm is diffusely thickened

. The parietal peritoneum under the diaphragm is diffusely thickened  with a discrete mass

with a discrete mass  .

.

with loculated ascites. The abdominal findings are indistinguishable from peritoneal carcinomatosis, but the asbestos plaque is an important clue to the diagnosis of mesothelioma.

with loculated ascites. The abdominal findings are indistinguishable from peritoneal carcinomatosis, but the asbestos plaque is an important clue to the diagnosis of mesothelioma.

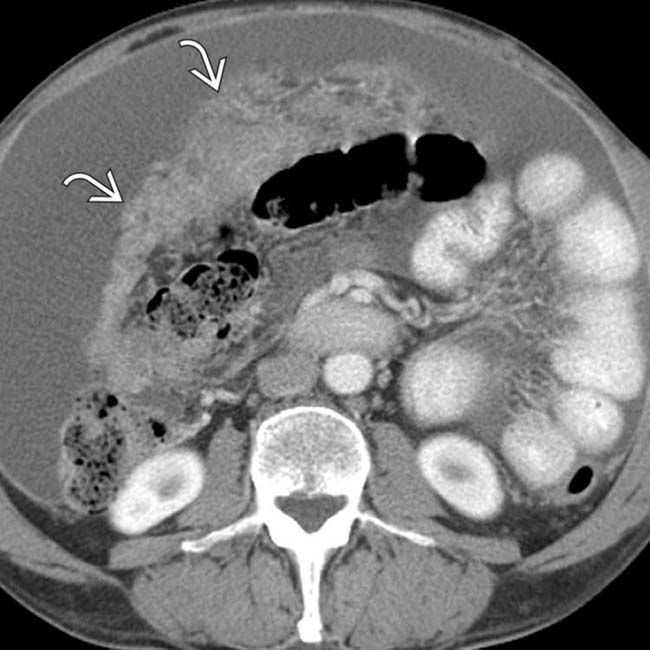

and encasement of bowel loops

and encasement of bowel loops  . Open biopsy confirmed malignant mesothelioma.

. Open biopsy confirmed malignant mesothelioma.

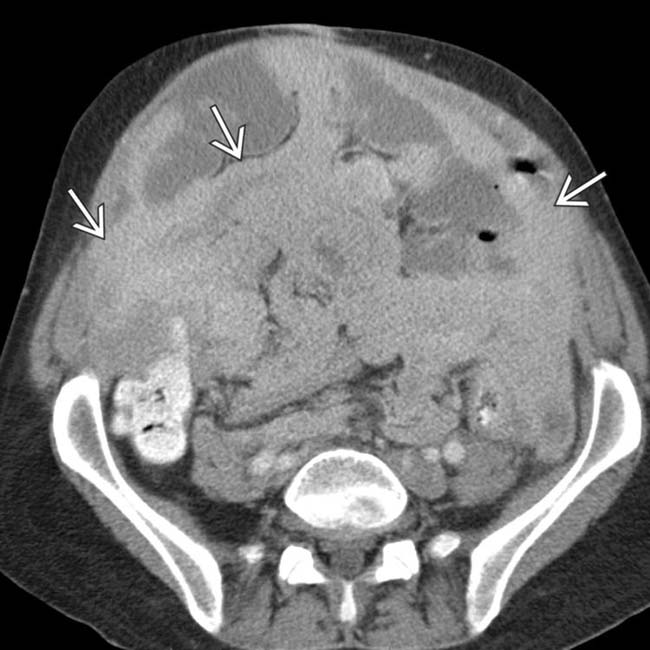

in the omentum abutting the anterior abdominal wall. Surgical biopsy confirmed malignant mesothelioma. Such an isolated mass is an unusual manifestation of the disease, which is usually widespread at the time of diagnosis.

in the omentum abutting the anterior abdominal wall. Surgical biopsy confirmed malignant mesothelioma. Such an isolated mass is an unusual manifestation of the disease, which is usually widespread at the time of diagnosis.IMAGING

General Features

CT Findings

• Omental and peritoneal stranding, nodularity, and discrete masses

• 2 primary forms

Diffuse (desmoplastic) peritoneal mesothelioma: Diffuse thickening of peritoneal surfaces and omentum with involvement of entire abdomen and multiple discrete masses

Diffuse (desmoplastic) peritoneal mesothelioma: Diffuse thickening of peritoneal surfaces and omentum with involvement of entire abdomen and multiple discrete masses

Diffuse (desmoplastic) peritoneal mesothelioma: Diffuse thickening of peritoneal surfaces and omentum with involvement of entire abdomen and multiple discrete masses

Diffuse (desmoplastic) peritoneal mesothelioma: Diffuse thickening of peritoneal surfaces and omentum with involvement of entire abdomen and multiple discrete masses

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Peritoneal Carcinomatosis

CLINICAL ISSUES

Presentation

and ascites

and ascites  , findings that may be seen in infectious, inflammatory, or malignant disease.

, findings that may be seen in infectious, inflammatory, or malignant disease.

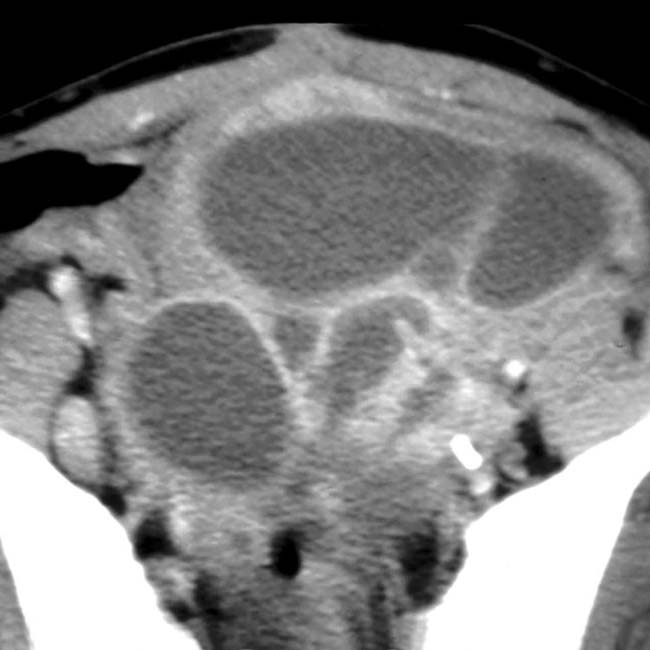

in the pelvis. At surgery, tumor was found along the entire surface of the peritoneal lining and omentum, and mesothelioma was confirmed.

in the pelvis. At surgery, tumor was found along the entire surface of the peritoneal lining and omentum, and mesothelioma was confirmed.

. No other primary malignancy was evident. At laparotomy, there was extensive tumor throughout the omentum and mesentery, diagnosed as primary peritoneal mesothelioma.

. No other primary malignancy was evident. At laparotomy, there was extensive tumor throughout the omentum and mesentery, diagnosed as primary peritoneal mesothelioma.

is somewhat difficult to recognize, as it surrounds the bowel and infiltrates the mesentery.

is somewhat difficult to recognize, as it surrounds the bowel and infiltrates the mesentery.

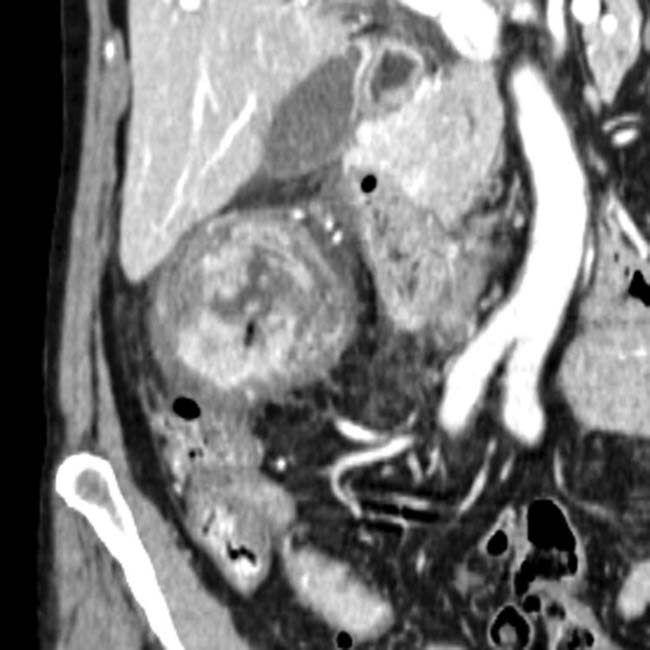

surrounding the liver and invading the abdominal wall. Other tumor implants

surrounding the liver and invading the abdominal wall. Other tumor implants  are found elsewhere in the omentum. Notice the relative lack of ascites

are found elsewhere in the omentum. Notice the relative lack of ascites  despite the large amount of tumor. This was found to represent peritoneal mesothelioma.

despite the large amount of tumor. This was found to represent peritoneal mesothelioma.

in the right hemithorax, also found to represent mesothelioma. Pleural and peritoneal mesothelioma in the same patient is quite rare.

in the right hemithorax, also found to represent mesothelioma. Pleural and peritoneal mesothelioma in the same patient is quite rare.

are also present.

are also present.

, due to diffuse tumor seeding along the leaves of the mesentery. In such cases, it is impossible to distinguish between primary peritoneal mesothelioma and metastases on the abdominal findings alone. This was found to be a case of mesothelioma.

, due to diffuse tumor seeding along the leaves of the mesentery. In such cases, it is impossible to distinguish between primary peritoneal mesothelioma and metastases on the abdominal findings alone. This was found to be a case of mesothelioma.