Abdominal injuries

Internal anatomy of the abdomen

Assessment of abdominal trauma

Specific intra-abdominal injuries

Introduction

Abdominal injuries are common in patients who sustain major trauma: approximately one-fifth of all trauma patients requiring operative intervention have sustained an injury to the abdomen (Feliciano et al. 2008, Jansen et al. 2008). Unrecognized abdominal injury continues to be the biggest cause of preventable death after truncal trauma (American College of Surgeons 2008); the resulting mortality rate in patients with abdominal trauma is reported at 13–15 % (Emergency Nurses Association 2007).

Identification of serious intra-abdominal pathology is often challenging, as mechanisms of injury often result in other associated injuries that divert attention from potentially life-threatening presentations (Barry et al. 2003, American College of Surgeons 2008). Patients sustaining significant blunt torso injury from a direct blow or deceleration, or a penetrating torso injury, must be considered to have an abdominal visceral or vascular injury (Barry et al. 2003, Alarcon & Peitzman 2007). Significant amounts of blood may be present in the abdominal cavity without outward changes in the appearance of the abdomen and with no obvious signs of peritoneal irritation (American College of Surgeons 2008, Jansen et al. 2008). Evaluation and stabilization of individuals with traumatic injury utilizing the advanced trauma life support protocols provide a paradigm for patient assessment and management that prioritizes trauma resuscitation, leading to an improvement in quality of care provided by all practitioners involved in the care of patients with trauma (Sikka 2004, Alarcon & Peitzman 2007).

Anatomy and pathophysiology

Flank

This is the area between the anterior and posterior axillary lines from the sixth intercostal space to the iliac crest. The thick abdominal wall musculature in this location, rather than the much thinner aponeurotic sheaths of the anterior abdomen, acts as a partial barrier to penetrating wounds, particularly stab wounds (Claridge & Croce 2007).

Internal anatomy of the abdomen

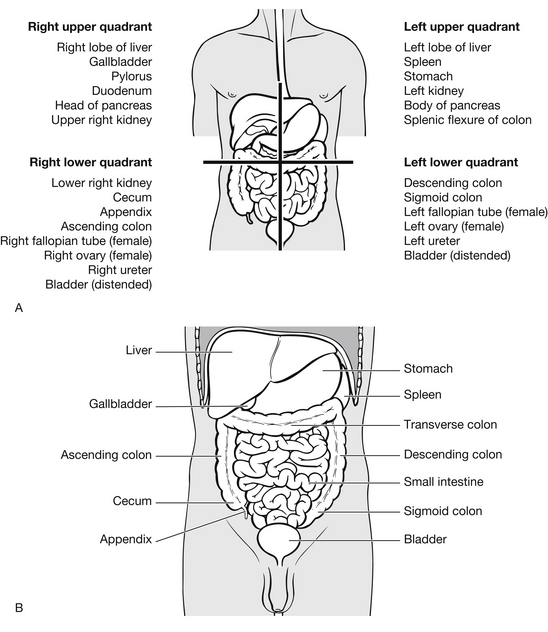

Peritoneal cavity

For convenience the peritoneal compartment may be divided into two parts, upper and lower. The upper peritoneal cavity is covered by the bony thorax and includes the diaphragm, liver, spleen, stomach and transverse colon; it is often referred to as the thoracoabdominal component of the abdomen. The diaphragm rises to the level of the fourth intercostal space on full expiration, which allows for injury to abdominal viscera from lower rib fractures and penetrating wounds below the nipple line. The lower peritoneal cavity contains the small bowel, parts of the ascending and descending colon, sigmoid colon and, in women, the organs of reproduction (Fig. 9.1).

Retroperitoneal space

The retroperitoneal space is the area posterior to the peritoneal lining of the abdomen, and contains the abdominal aorta, inferior vena cava, the pancreas, kidneys, adrenal glands, ureters, duodenum, and the posterior aspects of the ascending and descending colon and the retroperitoneal components of the pelvic cavity. Detecting injuries to the retroperitoneal viscera is difficult and may be delayed due to the obscurity of physical examination and the delay in appearance of signs and symptoms of peritonitis. Diagnostic peritoneal lavage does not sample this space and is therefore an unreliable test for injury to this area of the abdomen (Sikka 2004, Emergency Nurses Association 2007, American College of Surgeons 2008).

Mechanism of injury

Many injuries may not manifest during the initial assessment and treatment period, resulting in an undiagnosed or missed injury. The most common errors in the initial assessment of a patient with trauma are an inadequate primary and secondary survey and a low index of suspicion of significant injury. Both of these clinical failures may be attributed to an under-appreciation of and for the mechanism of injury and history of the traumatic episode (Sikka 2004, American College of Surgeons 2008, Weber et al. 2010).

Missed injury is defined as an injury that is not discovered during the initial evaluation and workup in the emergency department (ED) or operating room (Sikka 2004). The incidence of missed traumatic injuries (all injuries) has been broadly estimated to be 1–18 % in the paediatric population and 1–65 % in the adult population. More specifically, missed intra-abdominal injuries are common and carry an additional risk as delays in diagnosis are associated with additional surgery with mortality greater than 50 % (Jansen et al. 2008, Williams et al. 2009, Malinoski et al. 2010).

Intra-abdominal injuries are classically divided into blunt and penetrating trauma and will be described separately.

Blunt trauma

Blunt abdominal trauma is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality among all age groups (Jansen et al. 2008, Malinoski et al. 2010). Injury to intra-abdominal structures can be classified into two primary mechanisms of injury: compression forces and deceleration forces. Compression or concussive forces may result from direct blows or external compression against a fixed object (lower rim of steering wheel, lap belt, spinal column). Most commonly these crushing forces cause tears and subcapsular haematomas to the solid viscera. These solid viscera, which cannot change shape or stretch, are therefore vulnerable to damage, although they are protected by the thoracic skeleton. When great force is applied, they may be crushed between the lower ribs and the anterior vertebral column or the para-vertebral muscles (American College of Surgeons 2008, Rushings & Britt 2008). Fractures of the lower ribs should create a high level of suspicion of associated visceral damage or diaphragmatic injury (Guitron et al. 2009). Lap-belt marks have been correlated with rupture of small intestine and increased incidence of other intra-abdominal injury (Barry et al. 2003, Rushings & Britt 2008).

Sudden-deceleration injuries may be the result of motor vehicle trauma or falls from a height. The abdominal organs move at the same speed as the external framework of the body. The external framework may decelerate suddenly, as in the case of a car driver hitting the steering wheel, dashboard or windscreen during a high-velocity collision. The driver’s abdominal organs will continue at the pre-collision velocity, putting strain on or disrupting their points of attachment, until they meet another structure such as the abdominal wall.

Deceleration forces cause stretching and linear shearing between relatively fixed and free objects. Longitudinal shearing forces tend to rupture supporting structures at the junction between free and fixed segments (Rushings & Britt 2008). Classic deceleration injuries include hepatic tear along the ligamentum teres, intimal injuries to renal arteries and injuries to the arch of the aorta. Thrombosis and mesenteric tears can occur as a result of loops of bowel travelling from their mesenteric attachments.

Frequency: The true frequency of abdominal injury due to blunt trauma is unknown. According to the American College of Surgeons (2008), in patients undergoing laparotomy for blunt trauma the organs most frequently injured are the spleen (40–55 %), liver (35–45 %) and small intestine (5–10 %). In addition, there is a 15 % incidence of retroperitoneal haematoma in patients undergoing laparotomy for this type of injury.

Review of adult trauma databases in the US reveals that blunt trauma is the leading cause of intra-abdominal injury and that motor vehicle collisions are the leading mode of injury. Blunt injuries account for approximately two-thirds of all injuries, with a male to female ratio of 60:40. Peak incidence occurs in persons aged 14–30 years (Burkitt & Quick 2007, American College of Surgeons 2008).

Penetrating trauma

Throughout history, humans have created easily concealed personal weaponry designed initially for self-defense. Penetrating injuries are caused as a result of stabbing, accidental impalement, or high- or low-velocity projectiles, such as bullets or debris resulting from blast explosions. Each class of instrument or wounding source is associated with a different injury pattern of tissue damage by laceration or cutting. Abdominal organs are vulnerable to penetrating injuries not only through the anterior abdominal wall but also through the back, flank and chest below the fourth intercostal space, which may result in additional penetration of the abdomen through the diaphragm (Emergency Nurses Association 2007, Jurkovich & Wilson 2008).

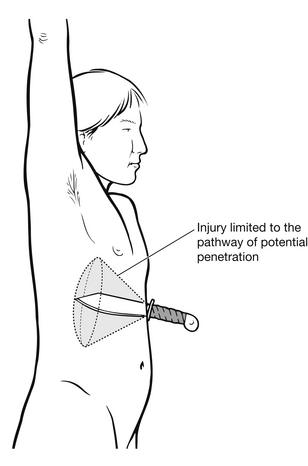

Stab wounds: Stab wounds traverse adjacent abdominal structures and most commonly involve the liver (40 %), small intestine (30 %), diaphragm (20 %) and colon (15 %) (American College of Surgeons 2008). Only 33 % of stab wounds penetrate the peritoneal envelope, however, and of these peritoneal violations only 50 % require intervention (Barry et al. 2003, Jurkovich & Wilson 2008). Knowledge of anatomic site, number of wounds, and type, size and length of blade will aid in determining the likely path and whether the peritoneum was breached (Fig. 9.2). Lacerated hollow organs result in haemorrhage and leakage of contained fluids into the peritoneal or retroperitoneal space, resulting in poorly defined and localized somatic pain. Pain radiating to the back or shoulder may provide a valuable clue to the presence of intraperitoneal blood, clots or air. Kehr’s sign is described as severe left shoulder pain caused by irritation of the left diaphragm and phrenic nerve, which is induced by laying the patient in a supine position and is indicative of free intra-abdominal blood and clots (Aitken & Niggemeyer 2007). Ecchymosis around the umbilicus (Cullen’s sign) or Grey-Turner’s sign, which is described as a bluish discoloration at the lower abdominal flanks and lower back, may appear with retroperitoneal bleeding originating in the kidney or with pelvic fractures. These signs may occur some hours or even days after initial injury but may be observed during nursing assessment in the ED (Aitken & Niggemeyer 2007, Bacidore 2010, Blank-Reid & Reid 2010).

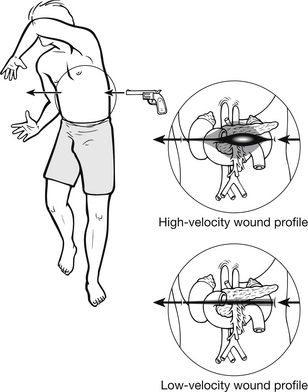

Gunshot injury: Gunshot injuries to the abdomen involve high energies and may damage organs remote from the site of penetration into the abdomen. It is important to establish the type of weapon used, whether handgun, shotgun or rifle, and the distance between the patient and the gun. Gunpowder around the bullet entry site will suggest firing at close range and is usually associated with an increase in injury severity. Up to 95 % of gunshot wounds to the abdomen result in visceral injury and require a surgical procedure (Feliciano et al. 2008). The amount of energy released is proportional to the mass and velocity of the bullet and also depends on the density of tissue involved. A low-velocity bullet from a handgun will release less energy and cause less injury than a high-velocity bullet from a rifle. Similarly, a high-mass bullet will cause more damage than a low-mass bullet of similar velocity. An accurate history involving the type of weapon used and the range at which it was fired is essential in order to assess the likely magnitude of visceral injury (American College of Surgeons 2008).

A bullet will release its energy in the abdomen in two ways: first, by direct contact with organs in its path. Bullets may take a non-linear path through the abdomen. A simple, straight line connecting entry and exit wounds may not indicate the actual path of the bullet. In cases where there is no exit wound, X-rays will locate the bullet. Second, bullets transfer energy in the form of pressure waves. These pressure waves may disrupt many organs not in the actual path of the bullet. Pressure waves result in cavitation, extending the diameter of injury to many times the actual diameter of the bullet. A low-velocity missile, from a gun travelling at 1000–3000 ft/s, creates a cavity 2–3 times the diameter of the missile (Feliciano et al. 2008). High-velocity missiles, i.e., those travelling at more than 3000 ft/s, create a cavity that may be 30–40 times the diameter of the bullet (Dickinson 2004, Blank-Reid & Reid 2010) (Fig. 9.3).

Figure 9.3 Potential injury path of high- and low-velocity bullets. (After Neff JA, Kidd PS (1993). Trauma Nursing: the Art and Science. St Louis: Mosby.)

Dense, solid viscera are more susceptible to cavitation than hollow organs. The sudden formation of a cavity increases intra-abdominal volume, creating a negative pressure, which may suck debris, such as clothing in through the entry wound resulting in gross intra-abdominal contamination. Gunshot wounds most commonly involve the small bowel (50 %), colon (40 %), liver (30 %), and abdominal vascular structures (25 %) (Barry et al. 2003, American College of Surgeons 2008).

Frequency: The frequency of penetrating abdominal injury across the globe relates to the industrialization of developing nations and, significantly, to the presence of military conflicts. The death rate from penetrating abdominal trauma spans the entire spectrum (0–100 %), depending on the extent of injury. Patients with violation of the anterior abdominal wall fascia without peritoneal injury have a 0% mortality and morbidity rate. An average mortality rate for all patients with penetrating abdominal trauma is approximately 5 % (Barry et al. 2003, Burkitt & Quick 2007).

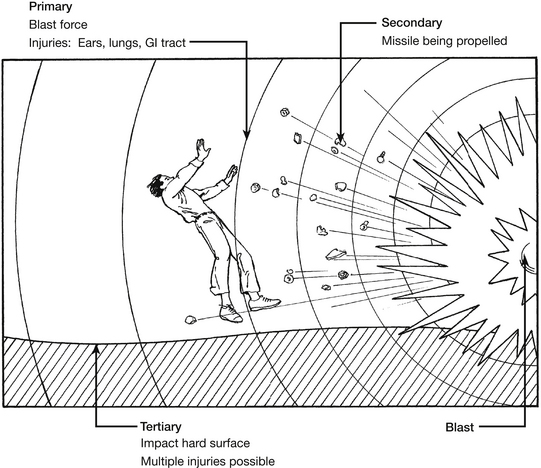

Blast injuries

The sudden, massive and catastrophic changes of pressure associated with blasts or explosions may damage the air-filled ‘hollow’ viscera of the gastrointestinal tract. The air within the viscera will transmit the force of the blast equally in all directions, leading to a general disruption or ‘bursting’ effect (Fig. 9.4).

Mannion & Chaloner (2005) categorize blast injuries into four categories: primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary. A patient may be injured by more than one of these mechanisms.

• Primary blast injury is caused solely by the direct effect of blast overpressure on tissue. Air is easily compressible, unlike water. As a result, a primary blast injury almost always affects air-filled structures such as the lung, middle ear and gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Other injuries include rupture of the eye and concussion without signs of head injury.

• Secondary blast injury is caused by flying objects that strike people. Injuries include penetrating ballistic or blunt injuries and eye penetration that can be occult.

• Tertiary blast injury is a feature of high-energy explosions. This type of injury occurs when people fly through the air and hit fixed objects such as walls. Fracture and traumatic amputations and closed and open brain injury are common with tertiary blast injuries.

• Quaternary blast-related injuries encompass all other injuries caused by explosions. For example, the collision of two jet airplanes into the World Trade Center on 11 September 2001 created a relatively low-order pressure wave, but the resulting fire and building collapse killed thousands (Arnold et al. 2004). The range of injuries from quaternary blasts includes flash, partial and full-thickness burns, crush injuries, closed and open brain injury, asthma or other breathing-related problems from dust, smoke or toxic fumes, angina, hyperglycaemia, hypertension, etc. (Taylor & Dawood 2005).

Frequency: Internationally, the incidence of blast injury is sporadic and infrequent and is dependent on the political (terrorism, occupational health and safety priorities) stability of the region. Mortality rates vary widely and are increased when explosions occur in closed or confined spaces (Owers et al. 2011). The presence of tympanic membrane rupture indicates that a high-pressure wave (at least 40 kPa, 6 psi) was present and may correlate with more dangerous organ injury. Table 9.1 provides an overview of explosion-related injuries.

Table 9.1

Overview of explosion-related injuries

| System | Injury or condition |

| Auditory | Tympanic membrane rupture, ossicular disruption, cochlear damage, foreign body |

| Eye, orbit, face | Perforated globe, foreign body, air embolism |

| Respiratory | ‘Blast lung’, haemothorax, pneumothorax, pulmonary contusion or haemorrhage, arteriovenous fistulae acting as sources of air embolism, airway epithelial damage, aspiration, pneumonitis sepsis |

| Digestive | Bowel perforation, haemorrhage, ruptured liver or spleen, sepsis, mesenteric ischaemia from air embolism |

| Circulatory | Cardiac contusion, myocardial infarction from air embolism, shock, vasovagal hypotension, peripheral vascular injury, air-embolism-induced injury |

| Central nervous injury | Concussion, closed and open brain injury, stroke, spinal cord injury, air-embolism-induced injury |

| Renal | Renal contusion or laceration, acute renal failure due to rhabdomylosis, hypotension, hypovolaemia |

| Extremities | Traumatic amputation, fractures, crush injuries, compartment syndrome, burns, cuts, lacerations, acute arterial occlusion, air-embolism-induced injury |

(After Taylor I, Dawood M (2005) Terrorism: the reality of blast injuries. Emergency Nurse, 13(8), 22–25; Centers for Disease Control (CDC) (2003) Explosions and Blast Injuries: A Primer for Clinicians. Atlanta: CDC.)

Assessment of abdominal trauma

History

An accurate history of the events leading to injury is crucial to identifying possible serious intra-abdominal pathology and can direct potential therapeutic priorities. The emergency nurse plays a vital role in gathering and collating information from a number of sources and disseminating that information to members of the trauma team (Cole et al. 2006). Information can be provided by the patient if alert, or by bystanders, police and emergency medical personnel. Pertinent information in assessing the patient injured in a motor vehicle collision includes the speed of the vehicle, type of collision (frontal or lateral impact, rear impact or rollover), vehicle intrusion into the passenger compartment, types of restraint, deployment of air bag, the patient’s position in the vehicle and status of passengers (American College of Surgeons 2008). The history surrounding a patient with penetrating trauma is also important, as it provides clues to the likely injury complex. Clues are gleaned from the injury location and from determination of the associated weapon (e.g., gun, knife) or injury-causing object. The number of gunshots heard, times stabbed, and position of the patient at the time of injury help describe the trajectory and path of the injuring object. Range also is important when assessing gunshot wounds. A careful history that assesses secondary and multi-cavity injuries is vital, as many victims sustain a blunt assault or fall from various heights after sustaining a penetrating trauma (Barry et al. 2003) (Boxes 9.1, 9.2).

Primary survey

The primary survey and resuscitation are examined in detail in Chapter 2. Assessment priorities relevant to abdominal trauma are outlined here:

• airway maintenance with cervical spine control

• breathing, ventilation, and oxygenation: injuries to the diaphragm or penetrating injuries involving the intra-thoracic abdomen and chest may compromise breathing

• circulation with haemorrhage control: gross external haemorrhage from the abdomen is rare. The abdomen, however, is a potential reservoir for a large volume of occult haemorrhage. Uncontrolled haemorrhage from damaged abdominal organs and vessels will cause hypovolaemia and death. Haemorrhage may remain uncontrolled because it is not detected. Early detection of haemorrhage is therefore essential for survival in any case of abdominal injury. Any hypovolaemia is treated with an intra-venous fluid challenge

• disability: neurological status

• exposure: completely undress the patient; care should be taken not to cut clothes across stab or bullet holes as this may destroy crucial forensic evidence. Hypothermia must be prevented by the use of overhead heaters or a warm-air heating system which can be easily controlled and adjusted according to the patient’s temperature

• adjuncts to primary survey and resuscitation: obtain arterial blood gas analysis and ventilatory rate, monitor exhaled CO2.

The goal of inserting a gastric tube is to relieve acute gastric dilatation, decompress the stomach before physical examination or performing a DPL (if indicated) and remove gastric contents, thus removing risk of aspiration (American College of Surgeons 2008). Special consideration should be given in circumstances where there is severe facial trauma or a suspicion of cribriform plate fracture, in which case the gastric tube may be inserted through the mouth.

Similar goals apply to the insertion of a urinary catheter in this phase, such as decompression of the bladder prior to DPL, in preparation for an abdominal examination and possible surgical entry into the abdomen and to allow monitoring of urinary output as an index of tissue perfusion. Haematuria if present raises a high index of suspicion of genitourinary trauma. Contraindications for urinary catheterization are blood at the urethral meatus, and the presence of a scrotal haematoma, both of which may indicate urethral injury. A disruption to the urethra may require a supra-pubic catheter to be inserted. A urinalysis is carried out on all patients and a urine pregnancy test is indicated in all females of childbearing age (American College of Surgeons 2008).

Secondary survey

The secondary survey does not begin until the primary survey (ABCDEs) has been completed, resuscitation is initiated and the patient is demonstrating normal vital functions (American College of Surgeons 2008). The secondary survey is a head-to-toe evaluation of the trauma patient and includes a complete history and physical examination of all systems and a reassessment of vital signs. A physical examination of the abdomen is performed as part of a complete secondary survey of the patient.

History

The AMPLE history is often useful as a mnemonic for remembering key elements of the history:

Inspection

The anterior and posterior abdomen as well as the lower chest and perineum should be inspected; injury patterns that suggest a potential for intra-abdominal trauma should raise suspicion (lap-belt abrasions or ecchymosis, steering wheel-shaped contusions). Obvious abnormalities including distension and asymmetry along with contusions, abrasions, penetrating wounds or exposed viscera should be noted and documented accurately (Blank-Reid & Reid 2010, Talley & O’Connor 2010).

Auscultation

Auscultation of the abdomen may be carried out to confirm the presence or absence of bowel sounds; however, this may prove difficult in a noisy ED. Auscultation should take place before percussion and palpation because these examinations can change the frequency of bowel sounds. Visceral injury may release blood or enteric contents into the peritoneal cavity, resulting in irritation of the bowel which may produce a paralytic ileus, and thus an absence of bowel sounds. If bowel sounds are heard in the chest it is an indication of diaphragmatic rupture with herniation of stomach or small bowel into the thoracic cavity (Bacidore 2010, Talley & O’Connor 2010).

Percussion

Percussion, or gentle tapping of the abdomen, produces a slight movement of the peritoneum. In the normal abdomen, percussion elicits dull sounds over solid organs and fluid-filled structures such as a full bladder and tympani over air-filled areas such as the stomach. If the peritoneum is injured, or irritated by free fluid released as a result of injury to viscera, this movement will cause pain. This is an unequivocal sign of intra-abdominal injury. Percussion may elicit subtle signs of peritonitis or isolate acute gastric dilatation by producing tympanic sounds or dullness due to haemoperitoneum. Percussion tenderness constitutes a peritoneal sign and mandates further evaluation and surgical consultation (Sikka 2004).

Log roll and cervical spine immobilization

While the patient is in a lateral position, a rectal examination should be performed. Bony fragments felt on rectal examination may indicate a fractured pelvis. Fresh blood in the rectum suggests a disrupted colon or rectum. A high-riding or absent prostate, in the male, may indicate a urethral transection, and contraindicates urinary catheterization. A vaginal examination is necessary in the female patient. Fractures of the pelvis may be discovered by direct palpation, and the integrity of the vaginal wall can be assessed. Examination of the gluteal region which extends from the iliac crests to the gluteal folds should also be carried out. Penetrating injuries to this area are associated with up to 50 % incidence of significant intra-abdominal trauma and mandate a search for intra-abdominal injury (American College of Surgeons 2008).

Radiological studies

A lateral cervical spine X-ray, an AP chest and a pelvic X-ray are the screening radiographs obtained in the patient with multi-system blunt trauma and continue to be important adjuncts to the primary survey. Jansen et al. (2008) argue that plain abdominal radiography has no role in the assessment of blunt abdominal trauma as it does not visualize abdominal viscera or detect free fluid and therefore cannot provide direct evidence of organ injury or indirect evidence of injury. Abdominal X-rays (supine, upright, lateral decubitus) may be useful in the haemodynamically stable patient to detect extra-luminal air in the retroperitoneum or free air under the diaphragm, both of which mandate urgent laparotomy (American College of Surgeons 2008). CT is regarded as the imaging modality of choice for evaluating the haemodynamically stable patient as it is 92–97.6 % sensitive and 98.7 % specific for detecting injuries which include the retroperitoneum and diaphragm (Hom 2010, Jansen et al. 2008).

The haemodynamically unstable patient with a penetrating abdominal wound does not require radiological screening in the ED. An upright chest X-ray is useful in the patient who is haemodynamically stable with penetrating injury above the umbilicus or who has a suspected thoracoabdominal injury. Chest X-ray can detect an associated pneumothorax or haemopneumothorax, or isolate air in the peritoneum. Supine abdominal X-ray may be useful to determine the track of a missile or bullet or the presence of retroperitoneal air; however, obtaining an abdominal X-ray is strongly discouraged as it delays more useful investigations (Raby et al. 2005).

Subsequent action

The management of blunt and penetrative trauma to the abdomen that follows the completion of the secondary survey is determined by the results of the physical examination and the circulatory status of the patient, i.e., whether there is any hypovolaemia, and the nature of the response to any fluid challenge measured by frequent recordings of vital signs. All blunt traumas should carry an associated high index of suspicion of intra-abdominal injury. Constant reassessment of the patient is necessary as it may take several hours for symptoms to develop, particularly splenic or duodenal injuries (Eckert 2005).

A three-stage response to abdominal examination exists:

1. No immediate action – observation only: a negative abdominal examination with no hypovolaemia. The abdominal examination should be repeated at frequent intervals.

2. Special diagnostic studies urgently required: an equivocal or unreliable abdominal examination in a multiply injured patient.

3. Immediate surgical exploration of the abdomen required: the need for urgent laparotomy is determined by history, findings on examination, and the results of investigations.

The following indications are commonly used to facilitate the decision-making process and are described by the American College of Surgeons (2008):

• blunt abdominal trauma with hypotension and clinical evidence of intraperitoneal bleeding

• blunt abdominal trauma with positive DPL or FAST

• hypotension with penetrating abdominal wound

• gunshot wounds traversing the peritoneal cavity or visceral/vascular retroperitoneum

• bleeding from the stomach, rectum, or genitourinary tract from penetrating wounds

• presenting or subsequent peritonitis

• free air, retroperitoneal air, or rupture of the hemidiaphragm

• contrast-enhanced CT demonstrates ruptured gastrointestinal tract, intraperitoneal bladder injury, renal pedicle injury or severe visceral parenchymal injury after blunt or penetrating trauma.

Special diagnostic studies

If there are early or obvious indications that a trauma patient will be transferred to another facility, time-consuming tests such as DPL, CT, contrast urologic and gastrointestinal studies should not be performed (American College of Surgeons 2008).

Diagnostic peritoneal lavage

Diagnostic peritoneal lavage was first described in 1965 (Schulman 2003, Jansen et al. 2008) and has been a primary diagnostic method of evaluation of abdominal injury. Although its application in practice has decreased significantly (Badger et al. 2009), DPL is a rapidly performed invasive procedure that is considered 95 % sensitive for detecting intraperitoneal haemorrhage (Emergency Nurses Association 2007). While DPL is a highly sensitive test it lacks specificity for evaluating the severity and identifying the location of the injured organ. It has a complication rate of approximately 1 % from mechanical injury to viscera during incision, or during insertion of the catheter (Schulman 2003). Bleeding from the incision, dissection or catheter insertion can cause false-positive results that may lead to unnecessary laparotomy (American College of Surgeons 2008, Jansen et al. 2008).

The preferred procedure involves an open or semi-open technique that is performed in the infra-umbilical area. In pregnant patients or patients with pelvic fracture an open supra-umbilical technique is preferred to avoid entering a pelvic haematoma or damaging the enlarged uterus. The procedure is performed under local anaesthetic, with lignocaine and adrenaline (epinephrine) to constrict the blood supply to the incised area. A catheter is inserted into the peritoneal cavity through the incision: free aspiration of blood, gastrointestinal contents, vegetable fibres or bile through the lavage catheter in the haemodynamically unstable patient mandates an urgent laparotomy. If gross blood (>10 mL) is not aspirated, lavage is performed with a litre of warmed Ringer’s lactate solution (10 mL/kg in a child). Following adequate mixing of peritoneal contents with fluid by compressing the abdomen and log rolling the patient, the effluent is allowed to free drain by gravity and is sent to the laboratory for analysis. A positive test is indicated by the presence of more than 100 000 RBC/mm3, or more than 500 WBC/mm3, or a Gram stain with bacteria present (American College of Surgeons 2008).

The indications for carrying out DPL are outlined in Box 9.3.

An absolute contraindication to DPL is an existing indication for immediate laparotomy. The disadvantages of DPL include utilizing an invasive technique and requiring the patient to have a gastric tube and indwelling catheter in place to avoid accidental perforation of bladder or stomach. Additional limitations include the inability of DPL to identify retroperitoneal or diaphragmatic injury as well as detecting hollow viscous injuries (Chughtai et al. 2009). The time required for laboratory test analysis and the relative contraindications in patients with prior abdominal surgery, obesity, advanced cirrhosis of the liver or patients in the third trimester of pregnancy may suggest consideration of other diagnostic tests such as FAST.

Focused abdominal sonography for trauma

The use of ultrasound in the evaluation of abdominal injury has been practised since the early 1970s and has grown in popularity as a diagnostic tool in the ED setting particularly since the 1990s (Schulman 2003, Raby et al. 2005, Jansen et al. 2008).

Ultrasound can be used to detect with 98 % accuracy the presence of haemoperitoneum and visceral injury and it has 98–100 % specificity in locating the site of injury (Schulman 2003, Jansen et al. 2008). FAST provides a rapid, non-invasive, accurate and inexpensive means of diagnosing haemoperitoneum that can be repeated frequently (Raby et al. 2005, Kirkpatrick 2007). Even if ultrasonography reveals no obvious aetiology, it can facilitate diagnosis by excluding potentially life-threatening conditions. Emergency abdominal ultrasonography is indicated for the evaluation of aortic aneurysm, appendicitis, and biliary and renal colic, as well as of blunt or penetrating abdominal trauma (Chen et al. 2000, Richards et al. 2002, Kirkpatrick 2007).

The use of FAST is not intended to replace CT or DPL; rather, it is recommended as an adjunct diagnostic tool for rapid screening for potential abdominal injuries during the initial physical examination. It can be performed in the resuscitation room at the bedside while simultaneously performing other diagnostic or therapeutic procedures (Kirkpatrick 2007, Jansen et al. 2008).

Fast examination

Identification of haemoperitoneum by ultrasound is based upon experience and understanding of abdominal anatomy, therefore specific equipment in experienced hands is a requirement for utilizing such a tool. Current literature recommends that the use of FAST should be limited to clinicians who have completed a special training programme (Schulman 2003, American College of Surgeons 2008, Jansen et al. 2008).

A hand-held transducer is positioned on four key areas to evaluate fluid collection:

• to screen for life-threatening accumulation of pericardial fluid the transducer is placed left of the lower sternum and angled under the costal margin towards the patient’s shoulder

• to visualize the spleen and perisplenic area the transducer is placed between the 10th and 11th ribs on the left posterior axillary line

• to evaluate the perihepatic region, the transducer is placed between the 10th and 11th ribs on the right axillary line

• as blood may accumulate in dependent areas of the abdomen and pelvis, the transducer is placed above the symphysis pubis.

False negatives may result if FAST is performed early on in the patient’s care; at least 100 mL of fluid are needed to be detectable on scan (Schulman 2003).

Advantages of FAST include rapid access, quick performance time, non-invasive testing, easy repetition, and no requirement for patient transport (Eckert 2005, Kirkpatrick 2007). Unlike DPL, ultrasound is capable of locating the injury, testing is not compromised by previous laparotomy or contraindicated in pregnancy and it can be used on patients with clotting disorders. Performance of the test by a trained surgeon or emergency physician eliminates the waiting time for technicians. Reported studies have found that the use of ultrasound has reduced the need for CT (from 56 % to 26 %) and DPL (17 % to 4 %) and reduced overall hospital admission rates by 38 % (Branney et al. 1997).

A limitation of ultrasound is in detecting intestinal injury and estimating the amount of haemoperitoneum present. Interpretation of test results may be limited depending on the expertise of the operator and interpreter; it may also be unreliable in patients with obesity, ascites and subcutaneous emphysema. It is important that ultrasound is not used as the single diagnostic tool in evaluating patients with abdominal injury; rather it should be utilized in conjunction with serial physical examinations, DPL, CT scanning and re-evaluation by ultrasound (American College of Surgeons 2008, Jansen et al. 2008). The emergency nurse should be aware and anticipate the use of FAST in the early diagnostic phase of trauma patient care and understand the limitations of such a diagnostic test so that continued vital-sign monitoring and vigilance in patient assessment is maintained to avoid missed life-threatening injuries.

Computed tomography

Computed tomography (CT) scanning is a non-invasive radiological examination and since its introduction in the 1990s, CT has become increasingly important in trauma care (Sierink et al. 2012). It is considered the best method for identifying specific sites and amounts of bleeding, but may miss mesenteric or hollow-organ injury; also some specific injuries to the diaphragm and pancreas may be missed (Schulman 2003, Khan & Garner 2011). Although CT scanning is the most sensitive diagnostic tool for most abdominal injuries, it is costly and requires time to prepare and execute. It also greatly increases radiation exposure which, with liberal use, imparts a small but finite risk of later cancer, especially in younger patients (Kirkpatrick 2007). In most hospitals, the patient must be transported to the radiology department, which is contraindicated in the haemodynamically unstable patient. However turnaround times are decreasing as a result of new-generation multidetector helical scanners with faster image acquisition and also an increasing trend to locate scanners in or close to emergency departments (Jansen et al. 2008). CT may require the administration of intravenous or oral contrast, which can prove problematic where information on allergies is unknown. Additional limitations of CT include inability to perform the scan on an uncooperative patient (Table 9.2).

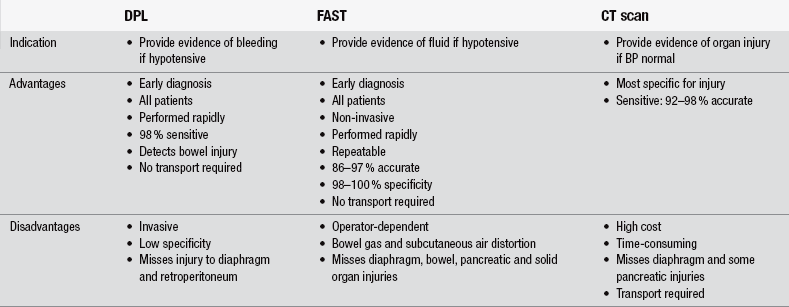

Table 9.2

Comparison of DPL versus FAST versus CT in blunt abdominal trauma

(Adapted from American College of Surgeons (2008) Advanced Trauma Life Support, 8th edn. Chicago: American College of Surgeons.)

Specific intra-abdominal injuries

Diaphragmatic injury in blunt trauma is relatively rare. It is estimated that it is seen in 3–5 % of all patients with blunt trauma who survive long enough to be admitted to hospital (Guitron et al. 2009). The diaphragm is integral to normal ventilation and injuries can result in significant compromise. A history of respiratory difficulty and related pulmonary symptoms may indicate a diaphragmatic disruption. The mechanism of diaphragm rupture is related to the pressure gradient between the pleural and peritoneal cavities. Lateral impact from a motor vehicle collision is three times more likely than any other type of impact to cause a rupture, since it can distort the chest wall and shear the ipsilateral diaphragm (Rushings & Britt 2008, Chen et al. 2010). Frontal impact from a motor vehicle collision can cause an increase in intra-abdominal pressure, which results in long radial tears in the posterolateral aspect of the diaphragm, its embryologic weak point. The majority (70–80 %) of diaphragmatic injuries occur on the left side, with 20–30 % occurring on the right side and 5–10 % occurring bilaterally (Chen et al. 2010).

Diaphragmatic tears do not occur in isolation; patients often have associated thoracic and/or abdominal injury or a concomitant head or extremity injury. Symptoms and signs of diaphragmatic rupture such as respiratory distress, cardiac disturbances, deviated trachea and bowel sounds in the chest are present in only a minority of patients initially assessed (Guitron et al. 2009, Chen et al. 2010). The less common right-sided ruptures are associated with more severe injuries such as tears of the juxtahepatic vena cava and hepatic veins as well as laceration of the liver. When herniation occurs on the right the liver is always present and the colon occasionally; such injuries result in haemodynamic instability and hypovolaemic shock. Reports on an autopsy series revealed that left- and right-sided diaphragmatic ruptures occurred almost equally; however, the more severe injuries associated with right-sided rupture caused more deaths and thus a lower rate of patient survival until diagnosis in hospital.

The rates of associated injury are: pelvic fractures 40 %, splenic rupture 25 %, liver laceration 25 %, thoracic aortic tear 5–10 %. Diagnosis may not be obvious and is made pre-operatively in only 40–50% of left-sided and 0–10 % of right-sided blunt ruptures. If diagnosis is not made in the first four hours it may be delayed for months or years; thus 10–50 % of injuries are diagnosed in a latent phase which occurs as a result of gradual herniation of abdominal contents into the pleural cavity. Diagnosis may be made later still in a third phase which is characterized by bowel or visceral herniation, causing obstruction and/or strangulation of stomach and colon. If herniation causes significant lung compression it can lead to tension pneumothorax, while cardiac tamponade has been described from herniation of abdominal contents into the pericardium (Chen et al. 2010). The incidence of diaphragmatic injury increases each decade as a result of increased occurrence of high-speed motor-vehicle accidents. Improved survival rates are likely to be due to improvements in pre-hospital and emergency care and earlier recognition and treatment of severe injury.

Duodenum

Duodenal injury is a rare condition and is typically associated with a direct blow to the epigastrium due to a traffic accident or sports injury. Delay in diagnosis is common because the duodenum lies in the retroperitoneum and often combines with other severe injury such as fractures or other organ injury. The incidence of traumatic duodenum injury, however, is lower than other abdominal injury, with reported rates of 3.5–12 % (Aherne et al. 2003). Morbidity is more dependent on other associated injuries than on the degree of the duodenal injury. Bloody gastric aspirate or retroperitoneal air on X-ray or abdominal CT scanning will raise suspicion for this injury (American College of Surgeons 2008) and will require further investigation. Treatment is often simple surgical repair but is dependent on the extent and nature of injury to the duodenum and other concomitant injuries.

Solid organ injury

Spleen

Injury to the spleen is most commonly associated with blunt trauma. Fracture of ribs 10 to 12 on the left should raise suspicion of spleen injury, which ranges from laceration of the capsule or a non-expanding haematoma to ruptured subcapsular haematoma or parenchymal lacerations. The most serious types of injury are a severely fractured spleen or vascular tear that causes splenic ischaemia and massive blood loss; however, shock and hypotension are present in as few as 30 % of patients with splenic trauma (Bacidore 2010).

Liver

Hepatobilary and pancreatic trauma represent a significant management challenge for emergency clinicians. These injuries require a high index of suspicion, rapid investigation, and well-defined management protocols to ensure an optimal outcome with minimal long-term consequences (Oniscu 2006, Badger et al. 2009). Due to its size and location the liver is the most commonly injured solid intra-abdominal organ (Oniscu et al. 2006). Severity ranges from a controlled subcapsular haematoma and lacerations of the parenchyma to hepatic avulsion or a severe injury to the hepatic veins. Because liver tissue is very friable and the liver’s blood supply and storage capacity are extensive, a patient with liver injury can haemorrhage profusely and may need surgery to control bleeding. Prior to 1990, most blunt injuries were treated surgically to ensure haemostasis. It is now widely accepted that 50–80 % of liver injuries stop bleeding spontaneously and therefore a conservative approach is effective and relatively safe in haemodynamically stable patients who can be closely monitored (Oniscu et al. 2006, Badger et al. 2009).

Pancreas

Although less common than liver trauma, pancreatic injuries should be suspected in any patient with penetrating trauma to the trunk or following blunt compression of the upper abdomen. As with liver trauma, CT scanning is the main diagnostic procedure used to detect pancreatic trauma (Oniscu et al. 2006).

Genitourinary

Direct blows to the back or flank resulting in contusions, ecchymosis or haematoma are markers for potential underlying renal injury and warrant evaluation of the urinary tract (American College of Surgeons 2008). Contusion is the most common kidney injury and should be suspected in posterior rib fracture or fracture to the lumbar vertebrae. Other renal injuries include lacerations or contusion of the renal parenchyma, the deeper a laceration the more serious the bleeding. Deceleration forces may damage the renal artery: collateral circulation in that area is limited, therefore any ischaemia is serious and may trigger acute tubular necrosis.

Pelvic injury

The pelvis protects the organs within the pelvic compartment, transmits weight from the trunk to the lower limbs and has attachment points for muscles. A stable pelvis can withstand vertical and rotational physiological forces, but either fractures or ligamentous injuries can disrupt pelvic stability. Pelvic blood supply comes primarily from the iliac and hypogastric arteries, which run at the level of the sacroiliac joints. Those arteries are supplemented by a rich associated network, including the superior gluteal artery, which is susceptible to injury in posterior fractures, and the obturator and internal pudendal arteries, which can be injured in fractures of the ramus (Frakes & Evans 2004).

Road traffic accidents cause about 60 % of pelvic fractures; most of the remainder result from falls (Frakes & Evans 2004, O’Sullivan et al. 2005). Pelvic fracture is said to contribute to traumatic death but is not the primary cause. For patients with pelvic fracture who die, hypotension at the time of admission is associated with increased mortality (42 % vs 3.4 % with stable vital signs), as are head injuries requiring neurosurgery (50 % mortality); abdominal injuries requiring laparotomy (52 % mortality); concomitant thoracic, urological or skeletal injuries (22 % mortality). Survival is poorer for patients with open pelvic fractures and for pedestrians struck by cars (Frakes & Evans 2004, O’Sullivan et al. 2005). Genitourinary injuries are seen in association with 15 % of all pelvic fractures. The bladder, rectum and vagina may be punctured by fracture fragments, or the bladder may be ruptured by a direct blow if full of urine. The male urethra that passes through the prostate is relatively immobile; the rest of the urethra passes through the urogenital diaphragm, which is attached to the pubic rami. If the pelvis is fractured, this portion may shear from the rest at the apex of the prostate and the prostate is then displaced upwards. Injuries to the female urethra are rare.

Pelvic fractures can be accurately diagnosed through physical examination but a high index of suspicion for a fracture based on the mechanism of injury is essential. Abrasions, contusions, isolated rotation of the lower extremity and discrepancy in limb length may alert the emergency nurse to the presence of pelvic fracture (Frakes & Evans 2004, Bailey 2005). Gentle compression of the iliac crests is advised to assess for tenderness, crepitus and stability of the pelvic ring. Rocking the pelvis and repeated examination is contraindicated where pelvic fracture is suspected or diagnosed. Repeated examination and excessive or unnecessary movement can aggravate bleeding, displace a fracture or disrupt a pelvic haematoma (Frakes & Evans 2004, Bailey 2005, American College of Surgeons 2008). Immobilization tools and techniques range from a sheet wrapped around the pelvis causing internal rotation of the lower limbs, a commercially available pelvic splint and external fixation devices which may be inserted by the orthopaedic surgeon in the resuscitation room in order to limit blood loss (Tile et al. 2003, Emergency Nurses Association 2007) (see also Chapter 6).

Abdominal injuries in children

Injury continues to be the most common cause of death and disability in childhood (Rothrock et al. 2000, Wise et al. 2002, Advanced Life Support Group 2005) and injury morbidity and mortality surpass all major diseases in children and young adults (American College of Surgeons 2008). At least 25 % of children with multisystem injury have significant abdominal injury although most are due to blunt trauma, most frequently from motor-vehicle collisions. The priorities of assessment and management of the injured child are the same as in the adult although physically, emotionally, intellectually and socially they differ greatly from adults. Only the differences related to abdominal injuries are considered in this section.

Specific anatomy in children

Children are vulnerable to abdominal injury for a number of reasons. Children are small; therefore any blunt trauma is likely to affect more body systems than in a similar incident involving an adult. The abdominal wall is thin, and offers little protection to its contents. Children have relatively compact torsos with smaller anterior–posterior diameters, which provide a smaller area over which the force of injury can be dissipated. The ribs are more elastic, decreasing protection to the spleen, liver and kidneys. The diaphragm lies more horizontally, lowering and further exposing these organs, which are relatively larger than in adults, with less overlying fat and weaker abdominal musculature. The kidneys are also more mobile, and not shielded by perinephretic fat, as in adults. The bladder is superior to the protection of the pelvis, and therefore more vulnerable. Finally, abdominal injuries may cause diaphragmatic irritation and splinting, compromising ventilation (Day & Rupp 2003, Advanced Life Support Group 2005, Fleisher & Ludwig 2010).

Types and patterns of abdominal injury in children

The majority of abdominal injuries in children are caused by blunt trauma. Penetrating injuries are rare but the hypotensive child who sustains a penetrating abdominal injury requires prompt surgical intervention (Advanced Life Support Group 2005). Motor vehicle trauma, bicycle handlebar injuries, falls and non-accidental injury are the most common causes of abdominal injuries (Williams et al. 2009, Browne et al. 2010). As in adults, the spleen, liver and kidneys are the most commonly injured organs in the child victim of blunt trauma. The mortality of blunt abdominal trauma in children is directly related to the level of involvement: it is less than 20 % in isolated liver, spleen, kidney or pancreatic trauma; increases to 20 % if the gastrointestinal tract is involved; and increases to 50 % if major vessels are injured (Day & Rupp 2003, Williams et al. 2009).

Assessment of abdominal trauma in children

The primary survey is carried out as in adults, with the same priorities and aims. An examination of the abdomen is carried out as part of the secondary survey. The examination is the same as that for adults, with the following special considerations. Care should be taken to be gentle on palpation, as any pain will produce voluntary guarding, making assessment difficult. Children swallow air when crying and upset; this produces distension of the stomach, which makes assessment difficult, and may mimic the rigidity and distension found in intra-abdominal injury. A nasogastric or orogastric tube (in infants and patients with maxillofacial trauma) should be placed in the resuscitation phase before abdominal examination (American College of Surgeons 2008). Gastric decompression will facilitate abdominal examination and prevent aspiration of gastric contents if vomiting occurs (Saladino & Lund 2010). A urinary catheter of appropriate size should always be passed, unless contraindicated, in order to decompress the bladder and facilitate abdominal evaluation and close monitoring of urinary output (American College of Surgeons 2008).

Repeated, serial examinations are necessary in children with abdominal trauma because life-threatening abdominal injury may not be apparent upon the initial examination. Severe intra-abdominal haemorrhage in children can be masked by their ability to maintain normal blood pressure with large-volume blood loss. Abdominal injury can be obscured by concurrent extra abdominal injury such as head injury, thoracic trauma or fracture of the extremities (Day & Rupp 2003, Advanced Life Support Group 2005).

Diagnostic tests

Abdominal CT is the preferred diagnostic imaging modality to detect intra-abdominal injury in haemodynamically stable children who have sustained blunt abdominal trauma. CT is sensitive and specific in diagnosing liver, spleen and retroperitoneal injuries, which may be managed non-operatively. CT scanning is more frequently used in children because it and will confirm renal perfusion, can evaluate solid organs and the intestines (Advanced Life Support Group 2005, Hom 2010).

Ultrasonography is useful when available for the rapid, early evaluation of children with blunt abdominal trauma who are stable; in such patients it might provide an indication for immediate laparotomy (Wise et al. 2002).

The indications for diagnostic peritoneal lavage are the same as in adults; however, its use has been rendered virtually obsolete in the trauma setting by modern imaging modalities. The usefulness of the test is questioned in the presence of solid organ injury where little or no peritoneal fluid may be present (Advanced Life Support Group 2005). Advanced trauma life support protocol suggests that only the surgeon who will care for the injured child should perform the diagnostic peritoneal lavage (American College of Surgeons 2008).

Non-operative management

Surgical intervention is not always warranted for haemodynamically stable children with solid organ injuries. Non-surgical observation of selected solid organ injuries in children is a safe practice that improves patient outcome and resource utilization (Wise et al. 2002, Advanced Life Support Group 2005). Approximately 90 % of children with liver and spleen injuries can be managed non-operatively as haemorrhage associated with these injuries is often self-limiting (Advanced Life Support Group 2005). In contrast, approximately 50 % of children with pancreatic injuries require surgical intervention (Wise et al. 2002). When non-operative management is selected as the treatment option, care must be delivered in a paediatric intensive care facility where staff have the skill to carry out frequent repeated examination and the expertise available to intervene immediately should the child’s condition deteriorate (Fleisher & Ludwig 2010).

References

Advanced Life Support Group. Advanced Paediatric Life Support, fourth ed. London: British Medical Journal Publishing Group; 2005.

Aherne, N.J., Kavanagh, E.G., Condon, E.T., et al. Duodenal perforation after a blunt abdominal sporting injury: the importance of early diagnosis. Journal of Trauma. 2003;54:791–794.

Aitken, L.M., Niggemeyer, L. Trauma Management. In Elliott D., Aitken L., Chaboyer W., eds.: ACCCN’S Critical Care Nursing, third ed, Sydney: Elsevier, 2007.

Alarcon, L.H., Peitzman, A.B. Initial assessment and early resuscitation. In: Britt L.D., Trunkey D.D., Feliciano D.V., eds. Acute Care Surgery: Principles and Practice. New York: Springer, 2007.

American College of Surgeons. Advanced Trauma Life Support, eighth ed. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 2008.

Arnold, J.L., Halpern, P., Tsai, M.C., et al. Mass casualty terrorist bombings: a comparison of outcomes by bombing type. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2004;43(2):263–273.

Bacidore, V. Abdominal and genitourinary trauma. In Howard P.K., Steinmann R.A., eds.: Sheehy’s Emergency Nursing: Principles and Practice, sixth ed, St Louis: Mosby, 2010.

Badger, S.A., Barclay, R., Campbell, P., et al. Management of liver trauma. World Journal of Surgery. 2009;33(12):2522–2537.

Bailey, M.M. Staying on your toes when managing pelvic fractures. Nursing. 2005;35(10):32–34.

Barry, P., Shakeshaft, J., Studd, R. Abdominal injuries. In: Sherry E., Triou L., Templeton J., eds. Trauma. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Blank-Reid, C., Reid, P.C. Epidemiology and mechanism of injury. In Howard P.K., Steinmann R.A., eds.: Sheehy’s Emergency Nursing: Principles and Practice, sixth ed, St Louis: Mosby, 2010.

Branney, S., Moore, E., Cantrill, S., et al. Ultrasound-based key clinical pathway reduces the use of hospital resources for the evaluation of blunt abdominal trauma. The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection and Critical Care. 1997;42:1086–1090.

Browne, G.J., Noaman, F., Lam, L.T., Soundappan, S.V. The nature and characteristics of abdominal injuries sustained during children’s sports. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2010;26(1):30–35.

Burkitt, H.G., Quick, C.R.G. Essential Surgery: Problems, Diagnosis and Management, fourth ed. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2007.

Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Explosions and Blast Injuries: A Primer for Clinicians. Atlanta: CDC; 2003.

Chen, S.C., Wang, H.P., Hsu, H.Y., et al. Accuracy of ED sonography in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2000;18(4):449–452.

Chen, H.W., Wong, Y.C., Wang, L.J., et al. Computed tomography in left-sided and right-sided blunt diaphragmatic rupture: experience with 43 patients. Clinical Radiology. 2010;65(3):201–212.

Chughtai, T., Sharkey, P., Lins, M., et al. Update on managing diaphragmatic rupture in blunt trauma a review of 208 consecutive cases. Canadian Journal of Surgery. 2009;52(3):177–181.

Claridge, J.A., Croce, M. Abdominal Wall. In: Britt L.D., Trunkey D.D., Feliciano D.V., eds. Acute Care Surgery: Principles and Practice. New York: Springer, 2007.

Cole, E., Lynch, A., Cugnoni, H. Assessment of the patient with acute abdominal pain. Nursing Standard. 2006;20(38):56–64.

Day, M., Rupp, L. Children are different; pediatric differences and the impact on trauma. In: Czerwinski S.J., Maloney-Harmon P.A., eds. Nursing Care of the Pediatric Trauma Patient. St Louis: Saunders, 2003.

Dickinson, M. Understanding the mechanism of injury and kinetic forces involved in traumatic injuries. Emergency Nurse. 2004;12(6):30–34.

Eckert, K.L. Penetrating and blunt abdominal trauma. Critical Care Nurse. 2005;28(1):41–59.

Emergency Nurses Association. Trauma Nursing Core Course. Provider Manual, sixth ed. Chicago: ENA; 2007.

Feliciano, D.V.B., Mattox, K.L., Moore, E.E. Trauma, sixth ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008.

Fleisher, G.R., Ludwig, S. Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, sixth ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2010.

Frakes, M.A., Evans, T. Major pelvic fractures. Critical Care Nurse. 2004;24(2):18–30.

Guitron, J., Howington, J., LoCicero, J. Diaphragmatic injuries. In Sheilds T.W., LoCicero J., Reed C.E., Feins R.H., eds.: General Thoracic Surgery, seventh ed, Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2009.

Hom, J. The risk of intra-abdominal injuries in pediatric patients with stable abdominal trauma and negative abdominal computed tomography. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2010;17:469–475.

Jansen, J.O., Yule, S.R., Loudon, M.A. Investigation of blunt abdominal trauma. British Medical Journal. 2008;336(7650):938–942.

Jurkovich, G.J., Wilson, A.J. Patterns of penetrating injury. In Peitzman A.B., Rhodes M.C., Schwab W.C., Yealy D.M., Fabian T.C., eds.: The Trauma Manual: Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, third ed, Philidelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, 2008.

Khan, M.A., Garner, J.P. Investigations outside the resuscitation room. In: Smith J., Greaves I., Porter K., eds. Oxford Desk Reference: Major Trauma. Oxford: Oxford Medical Publications, 2011.

Kirkpatrick, A.W. Clinician-performed focused sonography for the resuscitation of trauma. Critical Care Medicine. 2007;35(5):162–172.

Luckman, J., Sorenson, K.C. Medical-Surgical Nursing. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1987.

McSwain, N. The Basic EMT: Comprehensive Prehospital Patient Care, second ed. St Louis: Mosby; 2003.

Malinoski, D.J., Patel, M.S., Yaker, D.O., et al. A diagnostic delay in 5 hours increases the risk of death after blunt hollow viscus injury. Journal of Trauma-Injury Infection and Critical Care. 2010;69(1):84–87.

Mannion, S.J., Chaloner, E. Principles of war surgery: ABC of conflict and disaster. British Medical Journal. 2005;330(7506):1498–1500.

Neff, J.A., Kidd, P.S. Trauma Nursing: the Art and Science. St Louis: Mosby; 1993.

Oniscu, G.C., Parks, R.W., Garden, O.J. Classification of liver and pancreatic trauma. HPB (Oxford). 2006;8(1):4–9.

O’Sullivan, R.E.M., White, T.O., Keating, J.F. Major pelvic fractures: identification of patients at high risk. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2005;87(4):530–534.

Owers, C., Morgan, J.L., Garner, J.P. Abdominal trauma in primary blast injuries. British Journal of Surgery. 2011;98(2):168–179.

Raby, N., Berman, L., deLacey, G. Accident and Emergency Radiology: A Survival Guide, second ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2005.

Richards, J.R., Schleper, N.H., Woo, B., et al. Sonographic assessment of blunt abdominal trauma: a 4-year prospective study. Journal of Clinical Ultrasound. 2002;30(2):59–67.

Rothrock, S.G., Green, S., Morgan, R. Abdominal trauma in infants and children: prompt identification and early management of life-threatening injuries. Part 1: Injury patterns and initial assessment. Paediatric Emergency Care. 2000;16(2):106–115.

Rushings, G.D., Britt, L.D. Patterns of blunt trauma. In Peitzman A.B., Rhodes M.C., Schwab W.C., Yealy D.M., Fabian T.C., eds.: The Trauma Manual: Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, third ed, Philidelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, 2008.

Saladino, R.A., Lund, D.P. Abdominal Trauma. In Fleisher G.R., Ludwig S., eds.: Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine, sixth ed, Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, 2010.

Schulman, C.S. A FASTer method of detecting abdominal trauma. Nursing Management. 2003;34(9):47–49.

Seidel, H.M., Ball, J.W., Dains, J.E., Benedict, G.W. Mosby’s Guide to Physical Examination, third ed. St Louis: Mosby; 1995.

Sierink, J.C., Saltzherr, T.P., Reitsma, J.B., et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of immediate total-body computed tomography compared with selective radiological imaging of injured patients. British Journal of Surgery. 2012;99(S1):52–58.

Sikka, R. Unsuspected internal organ traumatic injuries. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 2004;22(4):1067–1080.

Stillwell, S. Mosby’s Critical Care Nursing Reference Guide, second ed. St Louis: Mosby; 1996.

Talley, N.J., O’Connor, S. Clinical Examination: A Systematic Guide to Physical Diagnosis, sixth ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2010.

Taylor, I., Dawood, M. Terrorism: the reality of blast injuries. Emergency Nurse. 2005;13(8):22–25.

Tile, M., Helfet, D.L., Kellem, J.F. Fractures of the Pelvis and Acetabulum. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2003.

Weber, J.M., Jablonski, R.A., Penrod, J. Missed opportunities: Under-detection of trauma in elderly adults involved in motor vehicle crashes. Journal of Emergency Nursing. 2010;36(1):6–9.

Williams, B.G., Hlaing, T., Aaland, M.O. Ten-year retrospective study of delayed diagnosis of injury in pediatric trauma patients at a level 11 trauma center. Pediatric Emergency Care. 2009;25(8):489–493.

Wise, B.V., Spears, S., Wilson, M.E. Management of blunt abdominal trauma in children. Journal of Trauma Nursing. 2002;9(1):6–14.