CHAPTER 24 Abdominal Hernias and Gastric Volvulus

DIAPHRAGMATIC HERNIAS

Cause and Pathogenesis

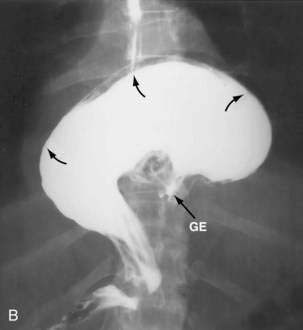

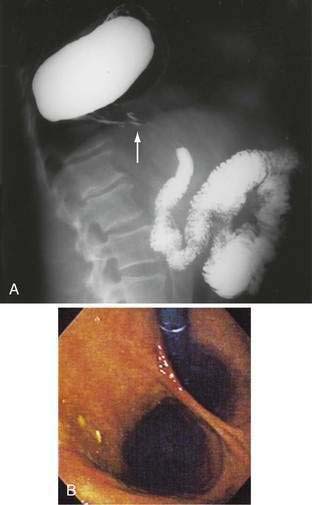

Paraesophageal hernias (type 2) occur when the stomach protrudes through the esophageal hiatus alongside the esophagus. The gastroesophageal junction typically remains in a normal position at the level of the diaphragm because there is preservation of the posterior phrenoesophageal ligament with normal anchoring of the gastroesophageal junction.1 The entire stomach can pass into the chest (Fig. 24-1A). Gastric volvulus (see later) may result. The omentum, colon, or spleen may also herniate. Patients with paraesophageal hernias may have a congenital defect in the diaphragmatic hiatus anterior to the esophagus. Most paraesophageal hernias contain a sliding hiatal component in addition to the paraesophageal component, and are thus mixed diaphragmatic hernias (type 3; see Fig. 24-1B).2 A barium study is often obtained to diagnose these defects. Very specific questioning of the radiologist with respect to two critical points will allow the clinician to make an accurate diagnosis:

Figure 24-1. A, Paraesophageal hernia. This barium radiograph shows a paraesophageal hernia complicated by an organoaxial volvulus of the stomach (see Fig. 24-6). The gastroesophageal junction remains in a relatively normal position below the diaphragm (arrow). The entire stomach has herniated into the chest and the greater curvature has rotated anteriorly and superiorly. B, Combined hernia in a different patient. A retroflexed endoscopic view of the proximal stomach shows the endoscope traversing a sliding hiatal hernia adjacent to a large paraesophageal hernia.

(A courtesy of Dr. Herbert J. Smith, Dallas, Tex.)

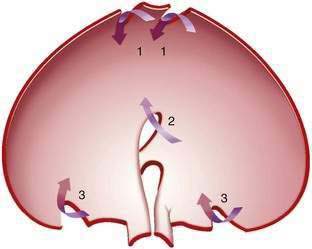

Congenital diaphragmatic hernias result from failure of fusion of the multiple developmental components of the diaphragm (Fig. 24-2). The diaphragm is derived from the septum transversum (separating the peritoneal and pericardial spaces), the mesentery of the esophagus, the pleuroperitoneal membranes, and muscle of the chest wall. Morgagni hernias form anteriorly at the sternocostal junctions of the diaphragm and Bochdalek hernias posterolaterally at the lumbocostal junctions of the diaphragm (Fig. 24-3).3 Bochdalek hernias manifest immediately after birth and are commonly associated with pulmonary hypoplasia.

Post-traumatic diaphragmatic hernias are caused by blunt trauma (e.g., motor vehicle accidents) in about 80% of cases, and to penetrating trauma (e.g., stab wounds or gunshots) in the remainder. During blunt trauma, abrupt changes in intra-abdominal pressure may lead to large rents in the diaphragm. Penetrating injuries often cause only small lacerations. Blunt trauma is more likely than penetrating trauma to lead eventually to herniation of abdominal contents into the chest because the defect is usually larger. The right hemidiaphragm is somewhat protected by the liver during blunt trauma. Thus, 70% of diaphragmatic injuries from blunt trauma occur on the left side.4–6 Diaphragmatic injury may not result in immediate herniation but, with time, normal negative intrathoracic pressure may lead to gradual enlargement of a small diaphragmatic defect and protrusion of abdominal contents through the defect.7 Stomach, omentum, colon, small bowel, spleen, and even kidney may be found in a post-traumatic diaphragmatic hernia.

Incidence and Prevalence

In the United States and Canada, a large proportion of adults undergoing upper gastrointestinal barium radiographs are found to have a small hiatal hernia. About 90% to 95% of hiatal hernias found by radiograph are sliding (type 1) hernias; the remainder are paraesophageal (type 2) or mixed (type 3).2 Most sliding hiatal hernias are small and of little clinical significance. Patients with symptomatic paraesophageal hernias are most often middle-aged to older adults.

Congenital hernias occur in about 1/2,000 to 10,000 births.8,9 Those hernias manifesting in neonates are most often Bochdalek hernias. With the routine use of prenatal ultrasound, congenital diaphragmatic hernias (CDHs) can be discovered in the prenatal period. The presence of intra-abdominal contents in the chest during fetal development results in significant hypoplasia of the lung. It is the degree of pulmonary dysfunction, not the presence of the hernia per se, that determines the child’s prognosis. Prenatal measures are then taken to prepare for the pulmonary hypoplasia that invariably accompanies a large CDH. Only a few Bochdalek hernias are first discovered in adulthood.10 Bochdalek hernias occur on the left side in about 80% of cases (see Fig. 24-3).11 Right-sided Bochdalek hernias usually contain liver in the right chest. Morgagni hernias make up about 2% to 3% of surgically treated diaphragmatic hernias.12,13 Although thought to be congenital, they usually manifest in adults and occur on the right side in 80% to 90% of cases. The incidence of post-traumatic diaphragmatic hernia is uncertain. Diaphragmatic injury occurs in about 5% of patients with multiple traumatic injuries.5,6

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Many patients with small simple sliding hiatal hernias are asymptomatic. The main clinical significance of the sliding hiatal hernia is its contribution to gastroesophageal reflux (see Chapter 43). In addition to heartburn and regurgitation, patients with large sliding hiatal hernias may complain of dysphagia or discomfort in the chest or upper abdomen. In a prospective, population-based study, the risk of iron deficiency anemia in adults was found to be increased by almost threefold.14 With chest radiography, a hiatal hernia may be noted as a soft tissue density or an air-fluid level in the retrocardiac area. Hiatal hernias are most often diagnosed on upper gastrointestinal barium studies. Computed tomography (CT) scanning can demonstrate the proximal stomach above the diaphragmatic hiatus. At endoscopy, the gastroesophageal junction is noted to be proximal to the impression of the diaphragm.

Cameron lesions or linear erosions may develop in patients with sliding hiatal hernias, particularly large hernias (see Chapters 19 and 52). These mucosal lesions are usually found on the lesser curve of the stomach at the level of the diaphragmatic hiatus (Fig. 24-4). This is the location of the rigid anterior margin of the hiatus formed by the central tendon of the diaphragm. Mechanical trauma, ischemia, and peptic injury have been proposed as the cause of these lesions. The prevalence of Cameron lesions in patients with hiatal hernias who undergo endoscopy has been reported to be about 5%, with the highest prevalence in the largest hernias. Cameron lesions may cause acute or chronic upper gastrointestinal bleeding.15 The presence of Cameron lesion(s) and occult gastrointestinal bleeding may prompt repair of the hiatal defect to aid healing of this defect.

Patients with paraesophageal or mixed hiatal hernias are rarely completely asymptomatic if closely questioned. About half of patients with paraesophageal hernias have gastroesophageal reflux.2,16,17 Other symptoms include dysphagia, chest pain, vague postprandial discomfort, and shortness of breath, and a substantial number of patients will have chronic gastrointestinal blood loss.18–20 If the hernia is complicated by gastric volvulus, acute abdominal pain and retching will occur, often progressing rapidly to a surgical emergency (see later, “Gastric Volvulus”). A paraesophageal or mixed hiatal hernia may be seen on a chest radiograph as an abnormal soft tissue density (often with a gas bubble) in the mediastinum or left chest. Upper gastrointestinal radiography is the best diagnostic study (see Fig. 24-1A). CT scanning can demonstrate that part of the stomach is in the chest. Lack of filling the gastric lumen with contrast or gastric wall thickening with pneumatosis can increase suspicion for a volvulus and associated gastric necrosis. Paraesophageal hernias are usually obvious on upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (see Fig. 24-1B), but the paraesophageal component of a large mixed hernia may be missed. Endoscopy may be difficult if the hernia is associated with gastric volvulus.

The clinical presentation of congenital diaphragmatic hernias varies greatly, from death in the neonatal period to an asymptomatic serendipitous finding in adults. Newborns with Bochdalek hernia have respiratory distress, absent breath sounds on one side of the chest, and a scaphoid abdomen.11 Most of these neonates are diagnosed in utero with routine use of prenatal ultrasound. Serious chromosomal anomalies are found in 30% to 40% of cases; the most common of these are trisomy 13, 18, and 21. Pulmonary hypoplasia occurs on the side of the hernia, but some degree of hypoplasia may also occur in the contralateral lung. Pulmonary hypertension is common. The major causes of mortality in infants with Bochdalek hernias are respiratory failure and associated anomalies. Prenatal diagnosis may be made sonographically by visualizing stomach or loops of bowel in the chest. The diagnosis of congenital diaphragmatic hernia in the prenatal period will make the pregnancy high risk. Pediatric surgeons are available at delivery to initiate extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), because the neonate will commonly need complete cardiopulmonary bypass because of the lack of pulmonary function. The hernia will then be repaired using a large mesh prosthesis once the child has stabilized from a pulmonary standpoint.

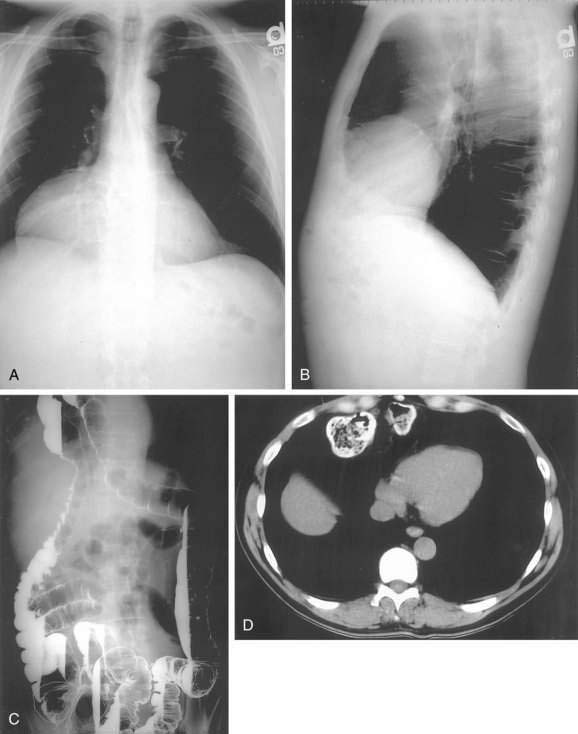

In older children and adults, a Bochdalek hernia may manifest as an asymptomatic chest mass. The differential diagnosis includes mediastinal or pulmonary cyst or tumor, pleural effusion, or empyema. Symptoms, when present, are caused by herniation of the stomach, omentum, colon, or spleen. About half of adult patients present with acute emergencies caused by incarceration. Gastric volvulus is common (see later). Other patients may have chronic intermittent symptoms, including chest discomfort, shortness of breath, dysphagia, nausea, vomiting, and/or constipation. The diagnosis may be suspected on a chest radiograph, particularly a lateral view. The key finding is a posterior chest mass because the defect of Bochdalek is posterior (see Fig. 24-3) as opposed to the Morgagni defect, which is anterior (Fig. 24-5). The diagnosis may be confirmed by barium upper gastrointestinal radiography or CT scanning.8,10,11

Morgagni hernias are most likely to manifest in adult life. They may contain omentum, stomach, colon, or liver. Bowel sounds may be heard in the chest if bowel has herniated through the defect. As with Bochdalek hernias, the diagnosis is often made by chest radiography, particularly the lateral view, because Morgagni hernias are anterior (see Fig. 24-5A and B). The contents of the hernia can be confirmed with barium radiography or CT scanning (see Fig. 24-5C and D). The differential diagnosis is similar to that of Bochdalek hernias. Many patients have no symptoms or nonspecific symptoms, such as chest discomfort, cough, dyspnea, or upper abdominal distress. Gastric, omental, or intestinal incarceration with obstruction and/or ischemia may cause acute symptoms.12,13

Post-traumatic diaphragmatic hernias cause respiratory or abdominal symptoms. After serious trauma, rupture of the diaphragm is often masked by other injuries.4 Penetrating injuries between the fourth intercostal space and the umbilicus should raise the level of suspicion of a diaphragmatic injury. Respiratory or abdominal symptoms manifesting several days to weeks after injury should suggest the possibility of a missed diaphragmatic injury. The diaphragm must be closely inspected to detect injury at the time of exploratory laparotomy because these injuries can be easily missed. Careful examination of the chest radiograph or CT scan is important, but is diagnostic in only half of cases. The use of rapid helical CT, especially with sagittal reconstruction, has facilitated the diagnosis.5,6 In patients on ventilatory support after trauma, positive intrathoracic pressure may prevent herniation through a diaphragmatic tear. However, on attempted ventilator weaning, herniation may occur, causing respiratory compromise. Symptoms may also manifest long after injury. Delays of more than 10 years are not uncommon.7 In such cases, the patient may not connect the acute illness with remote trauma.

Treatment and Prognosis

Simple sliding hiatal hernias do not require treatment. Patients with symptomatic giant sliding hiatal hernias, paraesophageal, or mixed hernias should be offered surgery. When closely questioned, most patients with type 2 or 3 hernias will have symptoms.1 In the past, paraesophageal hernias were thought to be a surgical emergency. However, it is now clear that the risk of progression to gastric necrosis is lower than initially believed.17 However, many experts suggest that surgery should be offered to all patients with paraesophageal hernias because some complication will develop in about 30% of patients if left untreated.2,18–20 In general, a selective approach to patients with large paraesophageal hernias is warranted; those with any symptoms that may be attributable to the hernia should be offered surgical intervention.

The extent of the preoperative evaluation needed for paraesophageal hernia repair is controversial. Many surgeons recommend routine preoperative evaluation with esophageal manometry and ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring because of the high prevalence of associated gastroesophageal reflux and esophageal motility disorders. The object of the evaluation is to determine which patients should have a fundoplication and whether to perform a complete or partial wrap. However, complete manometry is frequently not possible in these patients, and anatomic distortions make it difficult to place the pH probe in the correct location, making esophageal pH monitoring unreliable.21–24 The main use of manometry is to ensure that the patient has an excellent primary peristaltic wave rather than to identify the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure. Patients with dysphagia should be studied to ensure that significantly abnormal motility is not present. Many surgeons routinely add a fundoplication to all repairs to prevent postoperative reflux esophagitis and to fix the stomach in the abdomen. However, in patients with motility disorders, the surgeon may elect to perform a loose posterior wrap or simply a gastrostomy or gastropexy to fix the stomach intra-abdominally. Addition of gastropexy may, in fact, reduce the recurrence rate after hernia repair.25

The principles of surgery for hiatal or paraesophageal hernias include three main elements: (1) reduction of the hernia from the mediastinum or chest with excision of the hernia sac; (2) reconstruction of the diaphragmatic hiatus with simple closure or use of prosthetic mesh; and (3) fixation of the stomach in the abdomen with a wrap, gastropexy, or gastrostomy tube. These elements can be accomplished laparoscopically or via open operation and may be approached through the abdomen or the chest. Most patients are approached laparoscopically with a shorter hospital stay and less postoperative pain26 and an equivalent risk of recurrence. Reduction of chronic paraesophageal hernias from the chest can be difficult and may be approached through a combined thoracoscopic and abdominal procedure. Injury to the lung can occur with vigorous traction; however, as the diaphragmatic defect is central, rather than peripheral, as in the traumatic defect, intense lung adhesions are usually not present. Resection of the hernia sac can result in violation of the left chest, requiring chest tube placement. Reconstruction of the diaphragm can be performed by placing nonabsorbable sutures anterior or posterior to the esophagus.22,23 The use of prosthetic mesh has resulted in fewer recurrences.27–31 Fixation of the stomach in the abdomen is usually achieved by using a wrap, which provides some bolstering effect at the hiatus to keep the stomach in the abdomen and can reduce postoperative gastroesophageal reflux. Additional use of gastropexy, with suturing of the stomach to the abdominal wall or tube placement, may result in fewer recurrences.25

Patients with sliding hiatal or paraesophageal hernias may have shortening of the esophagus. This makes it difficult to restore the gastroesophageal junction below the diaphragm without tension, a key factor in decreasing recurrence. In such cases, an extra length of neoesophagus can be constructed from the proximal stomach (Colles-Nissen procedure).32 In this situation, a stapler is fired parallel to the axis of the esophagus along a bougie that is passed into the stomach, creating a lengthened esophagus. Alternatively, transmediastinal dissection of the esophagus for more than 5 cm into the chest will usually result in adequate intra-abdominal length of esophagus, without the need for additional stapling.33 Paraesophageal and mixed hernias can be repaired through the chest or abdomen, with open or laparoscopic techniques.2,18–20,26,34,35 Compared with open repair, laparoscopic repair is associated with less blood loss, fewer overall complications, and shorter hospital stay, and return to normal activities is faster. Long-term results are probably equal with either approach. Potential surgical complications include esophageal and gastric perforation, pneumothorax, and liver laceration; potential long-term complications may include dysphagia if the wrap is too tight or gastroesophageal reflux if the fundoplication breaks down or migrates into the chest. When examined closely, recurrence after paraesophageal hernia repair is 25% to 30%.36,37 However, the clinical impact of a recurrence may be minimal, because most of these patients remain symptom-free. Like other gastric ulcers, Cameron ulcers or erosions are initially treated with antisecretory medication (see Chapter 53). However, Cameron lesions may persist or recur despite antisecretory medication in about one third of patients, in which case surgical repair of the associated hernia may be required.15

The first priority of treatment for infants with Bochdalek hernias is adequate ventilatory support. Newer techniques of ventilation such as high-frequency oscillation and ECMO are very helpful in some cases. Ventilatory support allows infants to be stabilized before diaphragmatic repair. From 39% to 77% of infants survive the neonatal period after repair, but a significant number have long-term neurologic and musculoskeletal problems, and as many as 50% experience gastroesophageal reflux.11

Laparoscopic repair of Bochdalek hernias has been reported.10 Morgagni hernias have been repaired through the chest or abdomen, using open, thoracoscopic, and/or laparoscopic techniques.12,13,38–40

Acute diaphragmatic ruptures may be approached from the abdomen during exploratory laparotomy or through the chest. Diagnostic laparoscopy has been used in patients who are thought to have a high risk of diaphragmatic injury (e.g., after a stab wound to the lower chest). Chronic post-traumatic diaphragmatic hernias may be associated with extensive adhesions and lack of a peritoneal hernia sac. In such cases, repair is best done through the chest or by a combined thoracoscopic-abdominal approach, although laparoscopic repair has been reported.5,41

GASTRIC VOLVULUS

Cause and Pathogenesis

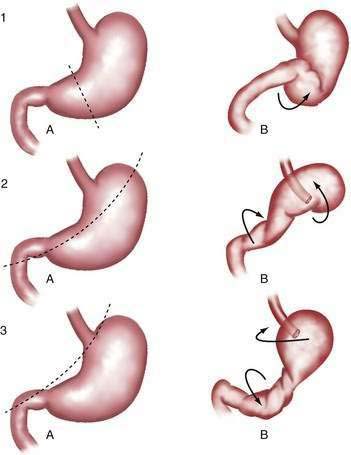

Gastric volvulus may be mesenteroaxial (40%) or organoaxial (60%; Fig. 24-6). In organoaxial volvulus, the stomach twists along its long axis. This axis usually passes through the gastroesophageal and gastropyloric junctions. The antrum rotates anteriorly and superiorly and the fundus posteriorly and inferiorly, twisting the greater curvature at some point along its length (see Fig. 24-6, 3A and 3B). Less commonly, the long axis passes through the body of the stomach itself, in which case the greater curvature of the antrum and fundus rotate anteriorly and superiorly (Fig. 24-7; see Fig. 24-6, 2A and 2B). This type of volvulus is commonly associated with a diaphragmatic hernia. Organoaxial volvulus is usually an acute event. Vascular compromise and gastric infarction may occur.

In mesenteroaxial volvulus, the stomach folds on its short axis, running across from the lesser curvature to the greater curvature (see Fig. 24-6, 1A and 1B), with the antrum twisting anteriorly and superiorly. In rare cases, the antrum and pylorus rotate posteriorly. Mesenteroaxial volvulus is more likely than organoaxial volvulus to be incomplete and intermittent, and to manifest with chronic symptoms. Mixed mesenteroaxial and organoaxial volvulus has also been reported.42

Incidence and Prevalence

The incidence and prevalence of gastric volvulus are unknown. It is difficult to estimate how many cases are intermittent and undiagnosed. About 15% to 20% of cases occur in children younger than 1 year of age, most often in association with a congenital diaphragmatic defect. The peak incidence in adults is in the fifth decade. Men and women are equally affected.43–45

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Acute gastric volvulus causes sudden severe pain in the upper abdomen or lower chest. Persistent unproductive retching is common. In cases of complete volvulus, it is impossible to pass a nasogastric tube into the stomach. Hematemesis is rare, but may occur because of an esophageal tear or gastric mucosal ischemia.45 The combination of pain, unproductive retching, and inability to pass a nasogastric tube is called Borchardt’s triad. Symptoms of acute gastric volvulus may be mistaken for a myocardial infarction or an abdominal catastrophe such as biliary obstruction or acute pancreatitis.43,44 If the volvulus is associated with a diaphragmatic hernia, physical examination may reveal evidence of the stomach in the left chest. Plain chest or abdominal films will show a large gas-filled viscus in the chest. A barium upper gastrointestinal radiograph will confirm the diagnosis. Upper endoscopy may show twisting of the gastric folds (Fig. 24-8). Endoscopy is not prudent if gastric ischemia is suspected.

Chronic gastric volvulus is associated with mild and nonspecific symptoms such as dysphagia, epigastric discomfort or fullness, bloating, and heartburn, particularly after meals. Symptoms may be present for months to years.43,45 It is likely that a substantial number of cases are unrecognized. The diagnosis should be suspected in the proper clinical setting if an upper gastrointestinal radiograph or CT scan shows a large diaphragmatic hernia, even if the stomach is not twisted at the time of the radiograph.46

Treatment and Prognosis

Acute gastric volvulus is an emergency. Nasogastric decompression should be performed if possible. If signs of gastric infarction are not present, acute endoscopic detorsion may be considered. Using fluoroscopy, the endoscope is advanced to form an alpha loop in the proximal stomach. The tip is passed through the area of torsion into the antrum, or duodenum if possible, avoiding excess pressure. Torque may then reduce the gastric volvulus.47 The risk of gastric rupture should be weighed against the possible benefit of temporary detorsion. Surgery for gastric volvulus may be done by open or laparoscopic techniques. In recent years, there has been a trend toward laparoscopic repair.44,48 After the torsion is reduced, the stomach is fixed by gastropexy or tube gastrostomy. Associated diaphragmatic hernia must be repaired.45,49 Combined endoscopic and laparoscopic repair or simple endoscopic gastropexy by placement of a percutaneous gastrostomy tube has been reported.47–52 Chronic gastric volvulus is treated in the same manner as acute volvulus. The surgeon may elect to treat an associated paraesophageal component in the usual manner, with repair of the diaphragm and wrap, if the patient is clinically stable. Acute gastric volvulus has carried a high mortality in the past. However, in one reported series, there were no major complications or deaths in 36 patients with gastric volvulus, including 29 who presented acutely.

INGUINAL AND FEMORAL HERNIAS

Cause and Pathogenesis

The abdominal wall is protected from hernia formation by several mechanisms. In the lateral abdominal wall, there are layers of muscles that together with intervening fascia, provide support. These muscles travel at oblique angles to each other and therefore handle forces in various planes, affording greater support than if they were parallel to each other. In the central abdomen, the bulky rectus abdominis muscles provide a barrier to herniation. Abdominal wall hernias occur in areas in which these muscles and fascial layers are attenuated, and they can be congenital or acquired. In the groin, there is an area that is prone to herniation bound by the rectus abdominis muscle medially, the inguinal ligament laterally, and the pubic ramus inferiorly. The aponeurosis of the transverses abdominis muscle provides the deep layer for this area. In this area, the external and internal oblique muscles thin to a fascial aponeurosis only, so that there is no muscular support of the transverse abdominal fascia and the peritoneum. Upright posture causes intra-abdominal pressure to be constantly directed to this area. During transient increases in abdominal pressure, such as occur with coughing, straining, or heavy lifting, reflex abdominal muscle wall contraction narrows the myopectineal orifice and tenses the overlying fascia (shutter mechanism).53 For this reason, hernias are not more common in laborers than in sedentary persons. However, conditions that chronically increase intra-abdominal pressure (e.g., obesity, pregnancy, and ascites) are associated with an increased risk of hernia. Chronic muscle weakness and deterioration of connective tissue (caused by aging, systemic disease, malnutrition, or smoking) promote hernia formation.

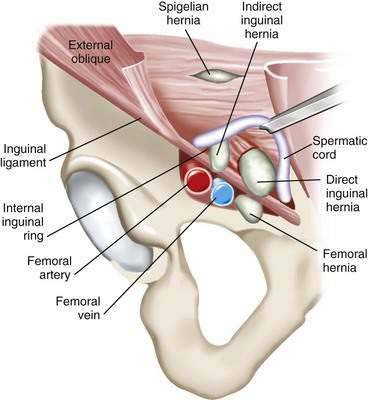

During embryologic development, the spermatic cord and testis in men (the round ligament in women) migrate from the retroperitoneum through the anterior abdominal wall to the inguinal canal, along with a projection of peritoneum (processus vaginalis). The defect in the abdominal wall (internal inguinal ring) associated with this process represents an area of potential weakness through which an indirect inguinal hernia may form (Fig. 24-9). The processus vaginalis may persist in up to 20% of adults, further predisposing to hernia formation. Direct inguinal hernias do not pass through the internal ring but rather protrude through defects in an area called Hesselbach’s triangle, bounded by the rectus abdominis muscle, the inferior epigastric artery, and the inguinal ligament (see Fig. 24-9). Therefore, indirect inguinal hernias travel with the spermatic cord (or round ligament) and are found lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels; direct hernias are found in the floor of the inguinal canal—an area supported only by the weak transversalis fascia—and are medial to the epigastric vessels.

Femoral hernias pass through the opening associated with the femoral artery and vein. They manifest inferior to the inguinal ligament and medial to the femoral artery (see Fig. 24-9).53 Clinical examination cannot easily differentiate indirect from direct inguinal hernias.54 The importance of distinguishing these two entities preoperatively is not critical because the operative approach and repair is identical. However, it is important to diagnose femoral hernias accurately because they can be mistaken for lymph nodes in the groin. Misdiagnosis of an incarcerated loop of bowel in a femoral defect as a lymph node can lead to fine-needle aspiration of the mass and bowel injury.

Incidence and Prevalence

The overall incidence of groin hernias in American men is 3% to 4% if determined through interview, and about 5% if determined by physical examination. The incidence increases with age, from 1% in men younger than 45 years to 3% to 5% in those older than 45 years. About 750,000 groin hernia repairs are done annually in the United States. Of these, 80% to 90% are done in men. Indirect inguinal hernias account for about 65% to 70% of groin hernias in men and women. In men, direct inguinal hernias account for about 30% and femoral hernias for about 1% to 2%, whereas in women the opposite is true. Groin hernias are somewhat more common on the right than on the left side.55

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Many groin hernias are asymptomatic. The most common symptom is a mass in the inguinal or femoral area that enlarges when the patient stands or strains. An incarcerated hernia may produce constant discomfort. Strangulation causes increasing pain. Symptoms of bowel obstruction or ischemia may occur. In a Richter-type hernia, pain from bowel strangulation may occur without symptoms of obstruction, as only one wall of the intestine is involved in the hernia. The patient should be questioned about risk factors for hernia formation (e.g., chronic cough, constipation, and symptoms of prostate disease). These factors, if not corrected prior to herniorrhaphy, can lead to recurrence.56–58

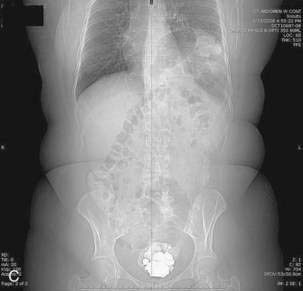

On physical examination, inguinal hernias present as a soft mass in the groin. The mass may be larger on standing or straining. It may be slightly tender. It may be possible to palpate the fascial defect associated with the hernia. The patient should be examined upright, the examiner’s finger should be inserted into the femoral canal, and a prolonged Valsalva maneuver should be initiated. It is normal to feel a small impulse against the examining finger with coughing; however, when a hernia is present, a prolonged Valsalva maneuver will result in the protrusion of the sac against the examiner’s finger. Direct and indirect hernias may be difficult to distinguish. Groin hernias may also be noted on a plain abdominal radiograph (Fig. 24-10), barium radiograph, sonogram, or CT scan.

Figure 24-10. Plain radiograph of a 28-year-old man with a giant incarcerated inguinal hernia.

(Courtesy of Dr. Michael J. Smerud, Dallas, Tex.)

Femoral hernias are more difficult to diagnose than other groin hernias. Two thirds of femoral hernias manifest as surgical emergencies. The correct diagnosis is often not made before surgery. The neck of femoral hernias is usually small. Even a small femoral hernia that is difficult to palpate may cause obstruction or strangulation. Richter’s hernias are most common in the femoral area, further complicating the diagnosis. Femoral hernias are most common in women, in whom clinicians may have a lower level of suspicion for hernia than in men. Femoral hernias also occur in children.59 Delay in diagnosis, strangulation, and need for emergency surgery are common.60–62 Any mass below the inguinal ligament and medial to the femoral artery should raise the suspicion of femoral hernia. Femoral hernias are commonly mistaken for femoral adenopathy or groin abscess. Obviously, bedside drainage of an incarcerated femoral hernia must be avoided and therefore liberal use of sonography or CT scanning is useful for distinguishing a hernia from adenopathy, abscess, or other mass.63 The radiologist should perform these examinations with and without a prolonged Valsalva maneuver to demonstrate even small defects.

Treatment and Prognosis

Many surgeons recommend repair of direct and indirect inguinal hernias, even if asymptomatic, but this is controversial. A study by the American College of Surgeons has shown that males with minimally symptomatic groin hernias can be safely watched.64,65 This study randomized 720 male patients to elective hernia repair or watchful waiting. Only 2 of the 364 patients in the watchful waiting arm study developed complications related to their hernia in 4.5 years. This suggests that minimally symptomatic patients can be watched safely and have their hernia repaired when symptoms increase. Femoral hernias must be repaired promptly because the risk of strangulation is very high.60–62 Groin hernias can be repaired using various techniques. Historically, tissue repairs have been performed. However, several studies have shown a decreased recurrence rate with the use of mesh resulting in tension-free repairs.66–70 These can be performed by open surgery or laparoscopically.

The traditional tissue-based repairs were performed exclusively until the 1990s. There are two key components to successful hernia repair: (1) high ligation of the hernia sac, which treats the direct defect; and (2) repair of the floor of the canal, which treats the indirect defect. Even if there is no direct component, a repair of the floor is routinely undertaken. These repairs involve approach to the inguinal canal through a small incision parallel to the inguinal ligament and centered over the internal inguinal ring. Dissection is continued through the external oblique muscle, exposing the internal inguinal ring. The cord structures are then isolated and explored thoroughly to identify an indirect hernia sac. This is ligated and transected. The floor of Hesselbach’s triangle is then reinforced and strengthened by apposing the lateral border of the rectus abdominis aponeurosis to the inguinal ligament (Bassini or Shouldice repair) or to Cooper’s ligament (McVay repair).70–72 Tissue repairs inherently are not tension-free and pose a greater risk of recurrence than tension-free mesh repairs (see later). However, in cases in which there is probable contamination (e.g., in a strangulated hernia), it is important to perform a primary tissue repair and not a mesh repair because there is a high risk of mesh infection.

Open mesh repairs are most commonly performed as described by Lichtenstein.66–68 These can be performed under local, regional, or general anesthetic.73,74 The two major components of successful repair remain, with high ligation of the sac; however, the floor is repaired using synthetic mesh to bridge the gap between the conjoint tendon (the edge of the rectus aponeurosis) and inguinal ligament. The mesh can be sutured or stapled in place. Mesh plug repairs have also been developed.75–77 In these cases, minimal dissection is undertaken and the mesh plug, which looks like a badminton shuttlecock, is laid into the defect and tacked in place with a few sutures. The mesh causes fibroblast ingrowth and scarring that leads to strengthening of the floor of the inguinal canal. Mesh repairs have the advantage of being somewhat simpler to perform than tissue repairs and have less tension, less acute pain, and a decreased rate of recurrence.58,66,76,78 Most inguinal hernia repairs in the United States are currently done with mesh.55 Bilateral, very large, or complex abdominal hernias can be repaired with a large mesh that reinforces the entire ventral abdominal wall. This is called giant prosthetic reinforcement of the visceral sac (GPRVS), or the Stoppa procedure.79–81

Repair of groin hernias may be done with open or laparoscopic techniques.82–86 Several series have compared open hernia repair with laparoscopic repair. The largest and most recent study was performed by the Veterans Cooperative group.86 Almost 1700 patients were followed for two years after being randomized to open versus laparoscopic repair of inguinal hernias. Patients who had their hernias repaired laparoscopically had less pain initially and returned to work one day sooner than those who had open repair. However, the recurrence rate was higher in the laparoscopic group (10% vs. 4% in the open group) and complication rates were higher and more serious in the laparoscopic group compared with the open repair group. In another multicenter, prospective, randomized study performed in the United Kingdom, open repair, primarily using mesh, was compared with laparoscopic repair.82 The recurrence rate after laparoscopic repair was 7% compared with 0% after open repair. As in the U.S. study, patients returned to normal activities more quickly after laparoscopic repair than after open repair. The overall complication rate was lower after laparoscopic repair, but three serious complications occurred after laparoscopy, and none after open repair.84 The results of the Veterans Cooperative group trial has changed the face of hernia repair in the United States. Patients with primary groin hernias are treated with open mesh repair unless they have a strong preference for a laparoscopic approach. Those with recurrent hernias or bilateral hernias can be considered for laparoscopic repair, which can be performed effectively in experienced hands.

Complications and Recurrence

Elective groin hernia repair has a mortality rate of less than 0.001% and serious complications are unusual.86–89 Lacerations of the bowel, bladder, or blood vessels may occur, particularly during laparoscopic repair, and may cause serious consequences if not detected early. Damage to the bowel may also occur during reduction of an incarcerated hernia.

Minor acute complications include acute urinary retention, seroma, hematoma, and infection. Serious infection occurs in less than 1% of cases. Damage to the spermatic cord may lead to ischemic orchitis. Tissue dissection predisposes to thrombosis of the venous drainage of the testis. Symptoms are swelling and pain of the cord and testis. The condition persists for 6 to 12 weeks and may result in testicular atrophy. Fortunately, this is a rare complication, occurring after about 0.04% of tissue repairs.90 Hydrocele or vas deferens injury occurs in less than 1% of cases. Damage to sensory nerves is not uncommon during inguinal hernia surgery, and can be related to the division or preservation of the ilioinguinal nerve as it traverses the inguinal canal.87,88,91,92 Chronic paresthesias and pain are reported by about 10% of patients, either caused by deafferentation or to a neuroma. This can often be treated by local nerve block or desensitization therapy.93

Some recurrent hernias are actually indirect hernias missed during the first hernia repair. The risk of recurrence is related to conditions that lead to tissue deterioration, such as malnutrition, liver or renal failure, steroid therapy, and malignancies. Patients with scrotal hernias and recurrent hernias are at higher risk for recurrence or rerecurrence, respectively.57 Recurrent hernias are also more common among smokers than nonsmokers. In patients with cirrhosis and no ascites or moderate ascites, inguinal hernia repair is reported to be safe, although the recurrence rate is increased.94 It is our preference to manage ascites aggressively prior to elective herniorrhaphy. Recurrence rates are higher with laparoscopic hernia repair compared with open herniorrhaphy.84,86 The routine use of mesh has reduced recurrences, because the learning curve for mesh repair is quicker than for laparoscopic or tissue repair. Recurrence rates are higher after repair of recurrent and femoral hernias than after primary repair of inguinal hernias. Overall, recurrence rates are higher after tissue repairs than after tension-free mesh repairs.58,69 For inguinal hernias, the most favorable reported recurrence rates for Canadian and Cooper’s ligament repairs have been about 1.5% to 2% for primary repairs and about 3% for repair of recurrent hernia.70,72 Reported recurrence rates for mesh repairs vary from 0% to 4% for primary repairs and can approach 14% for repairs of recurrent hernias.82,86

Inguinal Hernias and Colorectal Cancer Screening

Some practitioners recommend that patients age 50 years or older with inguinal hernias be screened for colorectal neoplasms before hernia repair. Several older prospective studies using sigmoidoscopy or barium enema to screen middle-aged or older men with inguinal hernias have reported the prevalence of polyps to be from 4% to 26% and of colorectal cancer to be from 2.5% to 5%.95,96 However, more recent data have clearly shown that there is no increased risk of colorectal cancer in patients who have groin hernias. In a prospective study of colonoscopy for screening of asymptomatic U.S. veterans, the prevalence of polyps was 37.5% and of colorectal cancer 1%.97 Thus, the prevalence of colorectal neoplasms is substantial in middle-aged or older men with or without inguinal hernias. In several more recent studies, the risk of colorectal cancer was found to be similar in patients with hernias (4% to 5%) compared with a control group that did not have hernias (3% to 4%).98–100 Large inguinal hernias, particularly incarcerated hernias, may cause difficulty during sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy. In such patients, it may be advisable to defer the examination until after the hernia repair. Incarceration of fiberoptic endoscopes within hernias has been reported.101,102

Inguinal Hernias and Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

Inguinal hernia and symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia coincide in 9% to 25% of men. Straining to void may cause worsening of inguinal hernia. Conversely, the risk of postoperative urinary retention after hernia repair is increased by prostatic hypertrophy, and older male patients with any symptoms of prostate disease should be counseled on the risk of urinary retention after hernia repair.103 With the advent of improved medical therapy for benign prostatic hyperplasia, most patients can be managed with medical therapy prior to herniorrhaphy. If elective inguinal hernia repair and transurethral prostatic resection are required, there are some surgeons that would consider performing these procedures concurrently.104,105 However, infection of mesh can be a significant problem, and therefore we recommend sequential surgery.

OTHER VENTRAL HERNIAS

INCISIONAL HERNIAS

Cause and Pathogenesis

Incisional hernias are caused by two main factors, patient-related and surgery-related. Patient-related factors include conditions that may increase intra-abdominal pressure, such as obesity, collagen vascular diseases, history of aneurysms, nutritional factors, and ascites.94,106,107 Conditions that impair healing, such collagen vascular disease in patients receiving glucocorticoid therapy, can also increase postoperative hernia formation.

Surgery-related factors include the type and location of the incision. For example, it is more common for hernias to develop after a vertical midline incision than after a transverse incision.106 This has led some surgeons to use transverse incisions in patients who are predisposed to hernias (e.g., patients with Crohn’s disease who are on glucocorticoids or other immunosuppressants). Development of a wound infection postoperatively can lead to a higher incidence of hernia formation. Placement of a stoma results in an intentional creation of a hernia through which the intestine runs. By placing these intentional hernias within the rectus muscle, rather than lateral to the rectus, the defect can be somewhat controlled. This results in a lower rate of parastomal hernias. Trocar hernias have become a more common occurrence with the increased use of laparoscopic surgery. The rate of hernia formation is related to the size of the trocar used, with trocars larger than 10 mm in diameter more commonly associated with hernia formation, and to the location of the trocar placement on the abdominal wall. Lateral trocar placement has a lower chance of hernia formation than midline placement. The fascial defect should be closed carefully if large trocars are used.108

Incidence and Prevalence

Incisional hernias are common after laparotomy. When followed carefully over a long period, as many as 20% of patients can be found to develop a hernia. This incidence increases to 35% to 50% of cases when there is wound infection or dehiscence.106,107 Up to 50% of such hernias manifest more than one year after surgery. Vertical incisions are more likely to be complicated by hernias than transverse incisions. Obesity, advanced age, debility, sepsis, postoperative pulmonary complications, and glucocorticoid use also increase the risk.109 Trocar site hernias are estimated to occur after 0.5% of laparoscopic cholecystectomies.110 They usually occur at the site of the largest trocar, which is typically larger than 10 mm in diameter. Parastomal hernias are reported to occur in as many as 50% of cases after stoma placement.111,112 Specific measures are taken at the time of surgery to decrease the incidence of hernia formation. For example, the smallest fascial defect is created within the rectus sheath, rather than lateral to it. The use of mesh in primary stoma placement may reduce the incidence of subsequent hernia formation; however, this routine use of mesh is controversial. Conditions that led to bowel dilation prior to stoma placement (e.g., obstruction) can result in subsequent bowel shrinkage after stoma placement. This can increase the space between the bowel wall and the fascia, facilitating hernia formation.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Incisional hernias can cause chronic abdominal discomfort. Because the fascial defect of incisional hernias is usually large, strangulation is unusual even with incarceration. Reduced ability to voluntarily increase intra-abdominal pressure interferes with defecation and urination. Lordosis and back pain may occur. Large incisional hernias may lead to eventration disease. With the loss of integrity of the abdominal wall, the diaphragm cannot contract against the abdominal viscera, but rather forces the viscera into the hernia. The diaphragm thus becomes inefficient. The hernia tends to enlarge. The viscera may lose the so-called right of domain in the abdominal cavity. Surgeons need to be careful about reducing and repairing these large hernias because the acute increase in abdominal pressure can lead to pulmonary failure and reduced venous return, resulting in an effective abdominal compartment syndrome.113,114 Techniques have been developed whereby the intra-abdominal cavity is insufflated gradually with air through a surgically placed indwelling catheter. This technique gradually stretches and expands the abdominal wall, preparing for successful reduction of the hernia contents. Trocar site hernias usually cause pain and a bulge at the trocar site. Because of the small opening, it is more likely that intra-abdominal contents could become strangulated in the defect. Richter’s hernia and small intestinal volvulus have been reported.108,110 Parastomal hernias often interfere with ostomy function and the fit of appliances. Incarceration and strangulation of bowel may occur.111

Treatment and Prognosis

Incisional hernias are best repaired with prosthetic mesh because the recurrence rate is substantially lower than after traditional tissue repair.106,107 The key element in hernia repair is to achieve a tension-free repair. In general, a nonabsorbable mesh is used to bridge the gap between the fascial edges. Every attempt is made to place a layer of peritoneum or hernia sac between the abdominal contents and the mesh. However, if this cannot be done, special double-sided mesh is available with expanded polytetrafluoroethylene on one side. This material does not stick to bowel and therefore is unlikely to erode into the intestine.113,114 If eventration disease is suspected, the abdominal wall may need to be stretched by repeated progressive pneumoperitoneum before repair. Recurrences of incisional hernia are reported in 4% to 29% of cases.106,115,116 Laparoscopic repair of ventral defects can be performed. There is some suggestion that laparoscopic repair results in fewer recurrences and lower morbidity.117 Laparoscopic repair is performed by insufflating the abdomen and gradually creating a working space by lysing adhesions carefully. Double-sided mesh is then placed in the retroperitoneal position and fixed by tacks and sutures.118 This can result in the sensation of a residual hernia, caused by retention of fluid in the hernia sac between the mesh and the skin, which can be frustrating for the clinician and patient. Chronic pain at suture or tack sites appears to be a greater issue with laparoscopic hernia repair when compared with open repair.119 Small and minimally symptomatic parastomal hernias may be treated with a modified ostomy belt. If surgery is necessary, there are several modes of treatment. The stoma can be relocated to the other side of the abdomen or to another quadrant of the abdomen. Primary repair of the parastomal defect is no longer considered adequate treatment and therefore mesh placement is advocated. A piece of mesh shaped with a keyhole defect, through which the stoma can be exteriorized, can be used.111,112 There are reports of this being done laparoscopically.120,121 To decrease the incidence of trocar site hernias, it is recommended that trocar ports be removed under direct vision and the defects sutured closed, particularly those defects related to trocars that are larger than 10 mm in diameter. Other risk factors for trocar site hernias include age older than 60 years, obesity, and increased operative time.110

Newer prosthetic materials that are biodegradable have become available. Pig mucosa infused with a collagen matrix can be used in the place of mesh in patients in whom there has been contamination (e.g., when bowel resection is necessary). These substrates are thought to be degradable and cause an influx of fibroblasts, resulting in a vigorous scar that can provide strength similar to mesh. With time, these substrates are degraded, leaving only autologous tissue. However, recurrence is still a significant issue and can occur in more than 30% of patients.122

EPIGASTRIC AND UMBILICAL HERNIAS

Cause and Pathogenesis

Epigastric hernias occur through midline defects in the aponeurosis of the rectus sheath (linea alba) between the xiphoid and the umbilicus. The defects are usually small and frequently multiple. Because of the location in the upper part of the abdominal wall, it is unusual for bowel to become incarcerated in epigastric hernias. More commonly, preperitoneal fat or omentum protrude through these hernias.123

Umbilical hernias in infants are congenital (see Chapter 96). They often close spontaneously. There is an increased incidence of congenital umbilical hernias in children of African descent.123 In general, these defects will close spontaneously by 4 years of age. If they are still evident after this age, surgical repair is indicated. In adults, umbilical hernias may develop consequent to increased intra-abdominal pressure because of ascites, pregnancy, or obesity.

Incidence and Prevalence

Epigastric hernias are found in 0.5% to 10% of autopsies. Many are asymptomatic or undiagnosed during life. They generally occur in the third through fifth decades. They are more common in men than in women.123 Umbilical hernias occur in about 30% of African American infants and 4% of white infants at birth, and are present in 13% and 2%, respectively, by 1 year of age.124 Umbilical hernias are more common in low birth weight infants than in those of normal weight. Umbilical hernias occur in 20% of patients with cirrhosis and ascites.125

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

The main symptom of epigastric hernia is upper abdominal pain. The pain is usually localized to the abdominal wall, rather than the deep visceral pain that accompanies intestinal pathology. A specific tender nodule or point of tenderness can be palpated in the nonobese patient. Diagnosis may be difficult, particularly in obese patients. However, symptoms are sometimes mistaken for those of a peptic ulcer or biliary disease. Sonography and CT may be helpful in the diagnosis.123,126

Umbilical hernias in children are usually asymptomatic. However, incarceration and strangulation may occur in children and adults. Spontaneous rupture of umbilical hernias may occur in patients with ascites and, rarely, in pregnant women.125,127 Skin changes with maceration and ulceration generally occur prior to frank rupture. Therefore, the findings of skin changes in a patient with an umbilical hernia should warrant urgent repair. Care must be taken when performing a therapeutic paracentesis in patients with umbilical hernias; the hernia must be reduced and kept reduced during the paracentesis because strangulation of umbilical hernias may occasionally be precipitated by rapid removal of ascites.128

Treatment and Prognosis

If surgery is performed for epigastric hernia, the linea alba should be widely exposed because multiple defects, called Swiss cheese defects, may be found. Umbilical hernias are most often left untreated in children because complications are unusual, and they usually close spontaneously if smaller than 1.5 cm in diameter. Repair should be considered if they are larger than 2 cm or if they are still present after 4 years of age.124 Repair of umbilical hernias should be recommended for adults if they are even minimally symptomatic or difficult to reduce. Techniques for repair of all abdominal wall defects rely on a tension-free repair to decrease the risk of recurrence. Open or laparoscopic techniques can be used to achieve this end. Data support the routine use of mesh in repair of these defects, because this results in a decrease in recurrences.129 Mesh is always used in laparoscopic repair. Once complications develop in patients with umbilical hernias, the prognosis worsens significantly. Those patients requiring bowel resection at the time of umbilical herniorrhaphy had a 29% mortality compared with no mortality in those that did not require bowel resection.130 Repair of umbilical hernias in patients with cirrhosis and ascites is a difficult clinical problem. In general, ascites should be aggressively controlled. If this is not possible, consideration should be given to transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) or liver transplantation (see Chapters 91 and 95). Spontaneous rupture of umbilical defects in patients with ascites portends a poor prognosis, with a mortality of 60%.125,128,131,132 Laparoscopic techniques and earlier repair of hernias in patients with cirrhosis should be considered, because the morbidity of elective repair appears not to be as high as once thought. Outcome after surgical repair is directly dependent on nutritional status and control of ascites. Control of ascites may require frequent paracentesis to keep the abdomen flat to allow healing. Topical sealants can be used to decrease the risk of leakage.127

SPIGELIAN HERNIAS

Cause and Pathogenesis

Spigelian hernias occur through defects in the fused aponeurosis of the transverse abdominal muscle and internal oblique muscle, lateral to the rectus sheath, most commonly just below the level of the umbilicus (see Fig. 24-9). This area is called the Spigelian fascia, named after the Belgian anatomist Adrian van den Spieghel. This fascia is where the linea semilunaris, the level at which the transversus abdominis muscle becomes aponeurosis rather than muscle, meets the semicircular line (of Douglas). The epigastric vessels penetrate the rectus sheath in this area. The combination of all these anatomic features can lead to a potential defect and a Spigelian hernia. The Spigelian fascia is covered by the external oblique muscle; therefore, Spigelian hernias do not penetrate through all layers of the abdominal wall.123

Incidence and Prevalence

Spigelian hernias (SHs) are rare. Approximately 1000 cases have been reported.133–137 The largest series of patients included 81 patients.138 SHs are twice as common in females as in males and are more common on the left side of the abdomen (60% left and 40% right).139 SHs generally occur in patients older than 40 years.123,140

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Spigelian hernias can be difficult to diagnose because the external oblique muscle overlies the defect in the deeper fascia. Only 75% of patients with SH are correctly diagnosed before surgery.139 Therefore, the examiner must have a high degree of suspicion when a patient complains of pain at the lateral edge of the rectus, inferior to the umbilicus. Careful examination will suggest that the pain originates in the abdominal wall and not in the peritoneal cavity. This determination is critical because SH can be mistaken for conditions such as acute appendicitis and diverticulitis.141,142 Frequently, only omentum is present in the hernia, but large or small bowel, ovary, appendix, or fallopian tube may herniate. A Richter’s hernia and bowel obstruction caused by incarcerated small intestine may occur.140,143 The differential diagnosis includes rectus sheath hematoma, lipoma, or sarcoma. Sonography and CT are the most useful adjuncts for diagnosing SH.123,144,145 An astute radiologist will perform these studies using various techniques, such as the Valsalva maneuver, to increase detection of even a small SH.

Treatment and Prognosis

Spigelian hernias may be approached by open or laparoscopic techniques. Laparoscopy can be helpful as a diagnostic tool in patients who are suspected of having SH, even if open repair is anticipated.146 The hernia can be best identified from within the peritoneal cavity. Preperitoneal laparoscopic techniques can be used, with the advantage of staying outside the peritoneal cavity.135 Intraperitoneal laparoscopic repair can be performed using mesh that is coated on one side so as not to stick to the underlying bowel.147 Laparoscopy results in decreased pain and decreased length of hospital stay compared with open techniques.148 However, these hernias are so rare that the surgeon should elect to repair them well in the manner with which they are the most experienced.137,149 As with other hernias, most SHs are closed using mesh repairs, a technique that appears to have a lower recurrence rate than primary repair.138,149

PELVIC AND PERINEAL HERNIAS

Cause and Pathogenesis

Most pelvic and perineal hernias occur in older female patients. Obturator hernias occur through the greater and lesser obturator foramina. The obturator foramen is larger in women than in men, and is ordinarily filled with fat. Marked weight loss thus predisposes to herniation. Sciatic hernias occur through the foramina formed by the sciatic notch and the sacrospinous or sacrotuberous ligaments. Abnormal development or atrophy of the piriform muscle may predispose to sciatic hernia. Sciatic hernias may contain ovary, ureter, bladder, or large or small bowel.150–152 Perineal hernias occur in the soft tissues of the perineum and are very rare. They may be primary or postoperative. Primary perineal hernias occur anteriorly through the urogenital diaphragm or posteriorly through the levator ani muscle or between the levator ani and coccygeus muscles. Secondary perineal hernias occur most often after surgery, such as abdominal-perineal resection, pelvic exenteration, perineal prostatectomy, resection of the coccyx, or hysterectomy. Radiation therapy, wound infection, and obesity predispose to the development of secondary perineal hernias.153–155

Incidence and Prevalence

Pelvic hernias are rare. Obturator hernias typically occur in older, cachectic, multiparous women. About 600 cases have been reported.150 In Japan, obturator hernias account for about 1% of all hernia repairs, but in the West, they account for 0.07% of all hernias.156,157 Sciatic hernias are even less common than obturator hernias, with fewer than 100 cases reported.123 They are most common in women. Perineal hernias are also rare. Primary perineal hernias are most common in middle-aged women. Anterior perineal hernias do not occur in men.155 Secondary perineal hernias occur after less than 3% of pelvic exenterations and less than 1% of abdominal-perineal resections for rectosigmoid cancer.153,154

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Obturator hernias (OHs) occur almost exclusively in older women and are more common on the right side.156,158,159 OHs commonly cause lower abdominal pain. Up to 88% of patients present with symptoms of small bowel obstruction.123,156 Because the hernia orifice is small, Richter’s hernia and strangulation are common, and 50% of patients present with bowel necrosis.160 There are three signs specific for incarcerated OH:

Occasionally, a mass may be palpable in the upper medial thigh or in the pelvis on pelvic or rectal examination. The diagnosis is difficult, often delayed, and usually not made preoperatively. Preoperative diagnosis is sometimes evident on a ultrasonogram or CT scan.150,157,161–164

Sciatic foramen hernias may manifest as a mass or swelling in the gluteal or infragluteal area, but are generally difficult to palpate because they occur deep to the gluteal muscles. Chronic pelvic pain may occur caused by incarceration of a fallopian tube and/or ovary. Impingement on the sciatic nerve may also produce pain radiating to the thigh. Intestinal or ureteral obstruction may occur. The differential diagnosis includes lipoma or other soft tissue tumor, cyst, abscess, and aneurysm. The diagnosis is often difficult and is made only at laparotomy or laparoscopy.123

In women, primary perineal hernias manifest anteriorly in the labia majora (pudendal hernia) or posteriorly in the vagina.155 In men, they manifest in the ischiorectal fossa. Primary and postoperative perineal hernias are usually soft and reducible. Most patients complain of a mass that produces discomfort on sitting. Because the orifice of the hernia is usually wide, incarceration is rare. If the bladder is involved, urinary symptoms may occur. Postoperative perineal hernias may be complicated by cutaneous ulceration. The differential diagnosis includes sciatic hernia, tumor, hematoma, cyst, abscess, and rectal or bladder prolapse.153,155

Treatment and Prognosis

The treatment of pelvic hernias is surgical. Laparoscopic repair of obturator and sciatic hernias has been reported.151,165 However, most patients with pelvic hernias present with an acute surgical condition, often bowel obstruction. Therefore, it is often necessary to perform an open procedure to manage the problem.166 The prognosis is poor when patients present with an acute illness. Nutritional depletion, advanced age, and poor medical health are all confounding variables. Repair of perineal hernias can be complex. When bowel resection is required, mesh placement is usually not used because of the high risk of infection. The advent of newer bioabsorbable products has allowed these materials to be used in these contaminated fields. Peritoneal flaps or muscle advancement flaps can be used to perform tissue repairs of these defects.156,160

LUMBAR HERNIAS

Cause and Pathogenesis

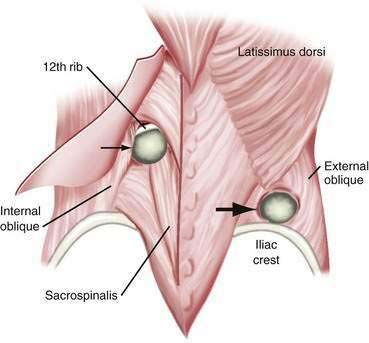

Lumbar hernias can occur in two separate triangular areas of the flank. The superior triangle (Grynfeltt’s lumbar triangle) is bound by the 12th rib superiorly, the internal oblique muscle inferiorly, and the sacrospinous muscles medially.167 The inferior triangle (Petit’s lumbar triangle) is bound by the latissimus dorsi muscle posteriorly, the external oblique muscle anteriorly, and the iliac crest inferiorly. Of all lumbar hernias, 20% are congenital; congenital lumbar hernias are commonly bilateral.168 Lumbar hernias are more common on the left than on the right side. This may be because the liver pushes the right kidney inferiorly in development, leading to protection of the lumbar triangles. Grynfeltt’s hernias are more common than Petit’s hernias. There is a 2 : 1 male predominance.169 Pseudohernia may occur in the lumbar area as the result of paresis of the thoracodorsal nerves. This is caused by loss of muscle control and tone, but there is no associated fascial defect. Causes include diabetic neuropathy, herpes zoster infection, and syringomyelia.170 Incisional and post-traumatic hernias also occur in the lumbar area. Flank incisions are used to access the retroperitoneum for procedures such as nephrectomies. These may be true hernias or pseudohernias caused by postoperative muscle paralysis. Motor vehicle accidents are the most common cause of post-traumatic lumbar hernias. If a lumbar hernia is found after a motor vehicle accident, it is critical to assume that the patient has other intra-abdominal injuries. These patients should undergo urgent laparotomy because more than 60% of them will have major intra-abdominal injuries (Fig. 24-11).171–173

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Lumbar incisional hernias generally present as a large bulge that may produce discomfort. These are especially evident when the patient strains or is in the upright position. Because of the large size of the defect, incarceration is not common. Inferior and superior lumbar triangle hernias may occur through small defects and can manifest with incarceration (24%) and strangulation (18%).169 The differential diagnosis includes lipoma, renal tumor, abscess, and hematoma. Bowel, mesentery, spleen, ovary, and kidney have been reported to herniate. Occasionally a small lumbar hernia may impinge on a cutaneous branch of a lumbosacral nerve, causing pain referred to the groin or thigh. CT scanning may aid in the diagnosis of lumbar hernia.174

Treatment and Prognosis

Closure of large lumbar hernias, as well as superior and inferior lumbar triangle hernias, often requires the use of prosthetic mesh or an aponeurotic flap. Identifying fascia with good tensile strength and repairing the defect with mesh in a tension-free manner is critical to preventing recurrence.175 Fixation of mesh to bony structures, such as the rib or the iliac crest, may be required. Preperitoneal as well as transperitoneal laparoscopic repair has been reported, and can result in less pain and quicker return to activity.176–179 Large and symptomatic lumbar pseudohernias should be treated by managing the underlying condition. Resolution has been reported following treatment of herpes zoster.170

INTERNAL HERNIAS

Internal hernias are protrusions into pouches or openings within the abdominal cavity, rather than through the abdominal wall. Internal hernias may be the result of developmental anomalies or may be acquired.180 Commonly, internal hernias develop after earlier abdominal surgery (e.g., after a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedure).

Cause and Pathogenesis

Internal hernias caused by developmental anomalies include paraduodenal, foramen of Winslow, mesenteric, and supravesical hernias. During gestation, the intestines are extra-abdominal. During fetal development, the mesentery of the duodenum, ascending colon, and descending colon becomes fixed to the posterior peritoneum. These segments of the bowel become reperitonealized and they attach to the retroperitoneum. Anomalies of mesenteric fixation may lead to abnormal openings through which internal hernias may occur. The extreme example of this is a complete intestinal malrotation, in which the ligament of Treitz does not assume its appropriate location to the left of the spine. This condition predisposes to midgut volvulus and can lead to extensive mesenteric ischemia (see Chapter 96).181,182 Lesser anomalies of fixation lead to defects such as paraduodenal and supravesical hernias. Abnormal mesenteric fixation may lead to abnormal mobility of the small bowel and right colon, which facilitates herniation. During fetal development, abnormal openings may occur in the pericecal, small bowel, transverse colon, or sigmoid mesentery, as well as the omentum, leading to mesenteric hernias. Unusual hernias can occur on structures such as the broad ligament.183

Paraduodenal hernias (PDHs) are thought to occur because of anomalies in fixation of the mesentery of the ascending or descending colon. PDHs occur on the left side in 75% of cases and have a 3 : 1 male predominance.184,185 Patients most commonly present in the fourth decade. In cases of left PDH, an abnormal foramen (fossa of Landzert) occurs through the mesentery close to the ligament of Treitz, leading under the distal transverse and descending colon, posterior to the superior mesenteric artery. Small bowel may protrude through this fossa and become fixed in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen. The mesentery of the colon thus forms the anterior wall of a sac that encloses a portion of the small intestine. Right PDH occurs in the same fashion through another abnormal foramen (fossa of Waldeyer), leading under the ascending colon.186

Foramen of Winslow hernias may occur when this foramen is abnormally large, particularly if there is abnormal mesenteric fixation of the small bowel and right colon. Most commonly, the right colon is abnormally fixed to the retroperitoneum, resulting in a patulous foramen of Winslow. Abnormally mobile small bowel and colon may herniate through the foramen of Winslow into the lesser sac. Symptoms of small bowel or colonic obstruction may occur; these may be intermittent as the hernia reduces spontaneously. Impingement on the portal structures can occur, but rarely results in obstruction of the bile duct or the portal vein.187 Gastric symptoms may also occur if the herniated bowel becomes distended because the herniated bowel loops are located in the lesser sac, posterior to the stomach.

Mesenteric hernias occur when a loop of intestine protrudes through an abnormal opening in the mesentery of the small bowel or colon. These mesenteric defects are thought to be developmental in origin, although they may also be acquired as a result of surgery, trauma, or infection. The most common area for such an opening is in the mesentery of the small intestine, most often near the ileocolic junction. Defects have been reported in the mesentery of the appendix, sigmoid colon, and a Meckel’s diverticulum.188–190 The intestine finds its way through the defects through normal peristaltic activity. Various lengths of intestine may herniate posteriorly to the right colon, into the right paracolic gutter (Fig. 24-12). Compression of the loops may lead to obstruction of the herniated intestine. Strangulation may occur by compression or by torsion of the herniated segment. Obstruction may be acute, chronic, or intermittent. The herniated bowel may also compress arteries in the margins of the mesenteric defect, causing ischemia of nonherniated intestine. Similar defects may occur in the mesentery of the small bowel, transverse mesocolon, omentum, and sigmoid mesocolon.

There are three types of mesenteric hernias involving the sigmoid colon. Transmesosigmoid hernias have no true sac. They occur through both layers of the mesocolon. Generally, the bowel becomes trapped in the left gutter, lateral to the sigmoid colon. Intermesosigmoid hernias are hernias that occur within the leaves of the sigmoid colon. This results in the hernia contents being contained within the mesentery of the sigmoid colon, generally posterior to the sigmoid colon. Intersigmoid hernias occur between the retroperitoneal fusion plane, between the sigmoid colon mesentery and the retroperitoneum. These hernias are contained in the retroperitoneum and generally lift and dissect the sigmoid colon on its mesentery out of the left gutter.180,191

Supravesical hernias protrude into abnormal fossae around the bladder. They are classified as internal or external supravesical hernias. Internal supravesical hernias occur within the abdomen and thus are internal hernias. They may extend anterior, lateral, or posterior to the bladder. External supravesical hernias occur outside the abdominal wall and appear much like indirect inguinal hernias. They usually contain small bowel but may contain omentum, colon, ovary, or fallopian tube.192–194

Acquired internal hernias may occur as a complication of surgery or trauma if abnormal spaces or mesenteric defects are created. Adhesions can create spaces into which bowel may herniate. Division of mesentery to create conduits, such as Roux-en-Y limbs, can lead to defects within the mesentery or around the reconstruction, which can result in herniation. With the increased popularity of the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) procedure for morbid obesity, there has been an increased incidence of unusual hernias related specifically to this surgery (see later).108

Retroanastomotic hernias may occur after gastrojejunostomy, colostomy or ileostomy, ileal bypass, or vascular bypass when an abnormal space may be created into which small bowel, colon, or omentum may herniate. The most common retroanastomotic hernia occurs after gastrojejunostomy, usually after gastric resection with Billroth II reconstruction. The afferent loop, efferent loop, or both, protrude into the space posterior to the anastomosis. Efferent loop hernias are about three times as common as afferent loop hernias, likely caused by the limited length of the afferent loop and the tethering effect of fixed structures involved in the afferent loop. For example, after a Bilroth II anastomosis, the afferent loop is connected to the duodenum, which is fixed, and the efferent loop is connected to the remainder of the small intestine. The efferent loop is therefore more mobile and can herniate into potential spaces. Colostomy, ileostomy, ileal bypass, and vascular bypass procedures (e.g., aortofemoral bypass) may also lead to the creation of a space into which organs can protrude. Renal transplant procedures are extraperitoneal, but an unrecognized inadvertent rent in the peritoneum can lead to pararenal intestinal herniation.180,191,195

Hernias after RYGB procedures have become more common with the increasing demand for this operation. These can be internal or external hernias through the incision or port sites (see earlier). Small bowel obstruction related to internal hernias after RYGB occurs in approximately 1.8% to 4% of patients.108,195 The incidence of small bowel obstruction is slightly higher after laparoscopic RYGB (3%) than after open RYGB (2%).108 There are three potential spaces created during the RYGB that can result in internal herniation. The Peterson defect occurs to the right of the jejunum as it traverses the mesentery of the transverse colon to reach the pouch of the stapled stomach. The endoscopist encounters this as a narrowing that occurs in the Roux limb at around 40 to 60 cm distal to the pouch-jejunum anastomosis. The jejunojejunostomy mesenteric defect occurs between the divided leaves of the small intestinal mesentery. The mesentery is divided to create the Roux limb, which is brought up to the gastric pouch. The two edges of the transected mesentery are then sewn together to prevent this defect. However, despite these measures, a defect can develop, resulting in herniation of intra-abdominal contents. The transverse mesocolic defect occurs through the defect in the transverse mesocolon through which the jejunal limb is brought to reach the stomach pouch. The Peterson and transverse mesocolic defects can be avoided by placing the jejunal limb in an antecolic position. In this case, the jejunum is not placed through a rent in the transverse mesocolon, but rather is brought anterior to the transverse colon. Although this makes intuitive sense, it is not always possible to achieve enough length of small intestinal mesentery to ensure an antecolic anastomosis without tension.196

Hernias can occur in the mesentery of the colon after colonoscopy.197 This likely occurs as a rent develops in the sigmoid mesocolon with insufflation of the colon. Hernias may occur through the broad ligament of the uterus, most commonly through tears occurring during pregnancy because 85% of these hernias occur in parous women. Other cases may be developmental or caused by surgery (e.g., uteropexy or salpingo-oophorectomy).198,199

Incidence and Prevalence

Internal hernias are rare. They are found in 0.2% to 0.9% of autopsies, but a substantial proportion of these remain asymptomatic.180 About 4% of bowel obstructions are caused by internal hernias. Internal hernias occur most often in adults.

Although half of developmental internal hernias are paraduodenal hernias, 1% or fewer of all cases of intestinal obstruction are caused by paraduodenal hernias. About 500 cases have been reported. They are more common in males than in females. They may occur in children or adults, but typically manifest between the third and sixth decades of life; most (75%) paraduodenal hernias occur on the left side.184,185,200–202 Fewer than 200 cases of foramen of Winslow hernia have been reported.203,204 Mesenteric hernias are rare and can occur at any age.180,191 Fewer than 100 cases of internal supravesical hernia have been reported. They are more common in men than in women. Almost all reported cases have occurred in adults, most commonly in the sixth or seventh decade.193,194 Similarly, fewer than 100 cases of broad ligament hernias have been reported.198,199 Postgastroenterostomy internal hernias have become less common because the frequency of surgery for peptic ulcer disease has declined. Other postanastomotic internal hernias are also rare.180 Internal hernias related to RYGB procedures have become more common because surgeries for morbid obesity have become more widely performed. Small bowel obstruction–related to internal hernias in most patients occurs with an incidence of 1.5% to 4% after RYGB.108,195

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Any of the various forms of internal hernias may manifest with symptoms of acute or chronic intermittent intestinal obstruction. The diagnosis is difficult in patients with chronic symptoms and is rarely made preoperatively in patients who present with acute obstruction and strangulation.180,191

Intestinal obstruction, which may be low grade, chronic, and recurrent, or may be high grade and acute, develops in approximately half of patients with paraduodenal hernias.184,201 Upper gastrointestinal tract contrast radiography has been shown to have excellent accuracy.200 Barium radiographs may show the small bowel to be bunched up or agglomerated, as if it were contained in a bag, and displaced to the left or right side of the colon. Small bowel is often absent from the pelvis. The colon may be deviated by the internal hernia sac. Bowel proximal to the hernia may be dilated.180,205 However, barium radiographs may be normal if the hernia has reduced at the time of the study. Endoscopy is not reliable for the diagnosis of paraduodenal hernias. Displacement of the mesenteric vessels can be noted if CT scanning with intravenous contrast or arteriography is performed.184,200,202 However, CT scanning may miss a paraduodenal hernia unless specific attention is paid to the relationship of the small intestine to the colon and mesenteric vessels.