Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

Perspective

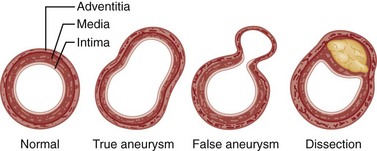

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is a true aneurysm, meaning a localized dilation of the aorta caused by weakening of its wall, and involving all three layers (intima, media, and adventitia) of the arterial wall (Fig. 86-1). A false aneurysm, or pseudoaneurysm, is a collection of flowing blood that communicates with the arterial lumen but is not enclosed by the normal vessel wall; it is contained only by the adventitia or surrounding soft tissue. Pseudoaneurysms can arise from a defect in the arterial wall or a leaking anastomosis after AAA repair.

AAA is distinct from aortic dissection, which sometimes is incorrectly called a “dissecting aortic aneurysm.” In aortic dissection, blood enters the media of the aorta and splits (dissects) the aortic wall (see Chapter 85). Aortic aneurysm and aortic dissection are very different diseases, with different clinical presentations, complications, diagnostic methods, and treatments.

An aneurysm can develop in any segment of the aorta, but most involve the aorta below the renal arteries. The diameter of the normal adult infrarenal aorta is approximately 2 cm, and a diameter of 3 cm or more defines an AAA.1

Epidemiology

AAA is a disease of aging, and the prevalence of AAA is expected to increase as the population of elderly patients grows. AAA is rare before the age of 50 years but is found in 2 to 5% of men older than 50.2,3 The average age at the time of diagnosis is 65 to 70, and men are affected much more often than women. The patient often has concomitant atherosclerotic occlusive disease of the coronary, carotid, or peripheral vessels, which may influence the clinical presentations, complications, and management.

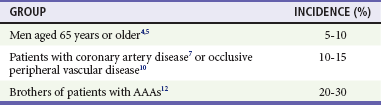

Several risk factors for the development of an AAA have been established, but risk factors are populational, not individual characteristics. An AAA can be found in 5 to 10% of elderly men who are screened with ultrasonography4,7 and in an even higher percentage of patients with coronary artery disease or peripheral vascular disease.4,6–8 The presence or absence of risk factors should not strongly influence diagnostic considerations in any individual patient (Table 86-1). A family history of an AAA is a very strong risk factor; those with an affected first-degree relative have a markedly increased risk of developing an AAA.9 Smoking is also a significant risk factor for AAA.10 Although awareness of high-risk groups can speed the recognition of AAAs, the consideration of AAA should not be restricted to patients in these groups. Recent data suggest that women may experience delays in diagnosis and worse operative mortality after ruptured AAA,11 and that up to half of AAAs in the United States occur in women, nonsmokers, and those younger than 65.12

Principles of Disease

AAAs have traditionally been attributed to atherosclerosis, but patients with advanced atherosclerosis have occlusive disease, not aneurysms. Recent data suggest that patients with AAA have biochemical abnormalities leading to the loss of elastin and collagen, the major structural components of the aortic wall.13 The propensity to form aneurysms may have a genetic basis, but the exact mode of inheritance is uncertain. The Society for Vascular Surgery recommends labeling the typical degenerative AAA as “nonspecific,” rather than “atherosclerotic,” to reflect this uncertainty surrounding the etiology.

Natural History

The most important factor determining the risk of rupture is the size of the aneurysm.14–17 The risk increases dramatically with increased aneurysm size, and most ruptured AAAs have diameters greater than 5 cm. The growth rate of the AAA, in addition to other anatomic factors, may also be important in determining the risk of rupture.18,19 Although rupture of aneurysms smaller than 4 cm is rare,16 no aneurysm is completely “safe.”3,20 Any aneurysm can rupture and cause the patient’s emergency department (ED) presentation.

Rupture of an AAA usually occurs into the retroperitoneum, where hemorrhage may be temporarily limited by clotting and tamponade at the rupture site, but 10 to 30% involve free intraperitoneal rupture, which is often rapidly fatal.21 Occasionally, rupture occurs into the gastrointestinal tract or the inferior vena cava.

Complications can also arise from an intact AAA. The walls of an AAA are often lined with clot and atheromatous material, which can embolize and occlude distal vessels.22 Aortic thrombosis may occur rarely. Patients can also have complications caused by impingement on adjacent structures.

In approximately 5% of AAAs, a dense inflammatory and fibrotic reaction develops in the aneurysm wall and adjacent retroperitoneal tissue. In these “inflammatory” AAAs, the periaortic fibrosis may incorporate and obstruct adjacent structures, such as the ureters or duodenum.23

Clinical Features

In most cases, an AAA is asymptomatic and is discovered incidentally on physical examination, on a radiologic study done for other reasons, or by an ultrasonography aneurysm screening program.1,24 Symptoms usually do not develop until the aneurysm ruptures.

Symptomatic aneurysms are usually fairly large and are often palpable. Likewise, the patient with an aneurysm large enough to warrant elective repair often has a palpable abdominal mass.25,26 However, an AAA may be difficult to palpate if the aneurysm is small or the patient is obese. Published reports indicate that 30 to 60% of unruptured aneurysms measuring 3.0 to 3.9 cm on ultrasonography can be detected by abdominal palpation; 50 to 70% of aneurysms measuring 4.0 to 4.9 cm and 75 to 85% of aneurysms 5 cm or larger can be palpated.25,26 These reports are based on the examination of patients with intact, asymptomatic aneurysms, with the examination specifically directed at sizing the aorta. The sensitivity is likely much lower when the abdomen is not palpated deeply, or in hypotensive patients or those with significant abdominal guarding. There is virtually no risk of causing aneurysm rupture by abdominal palpation.25

Physical examination may raise suspicion regarding an AAA even when the aorta is of normal size.25 A tortuous aorta may feel enlarged, and prominent aortic pulsations, especially in a thin patient, may simulate an aneurysm. Moreover, pulsations from a normal aorta may be transmitted to an adjacent abdominal mass. Nonetheless, clinical suspicion of AAA warrants further investigation.

An abdominal bruit is an uncommon finding in patients with AAAs. The presence of a bruit is also nonspecific, as bruits can originate in a stenotic renal, iliac, or mesenteric artery. A loud continuous bruit suggests the diagnosis of aortovenous fistula, a rare complication of AAAs.27

Thromboembolic complications can occur spontaneously or when atheromatous plaques are disrupted during invasive intravascular procedures. Large emboli can acutely occlude major vessels such as the iliac, femoral, or popliteal artery, causing acute painful lower extremity ischemia with absent distal pulses. Rarely, the aneurysm itself can thrombose, rendering both lower extremities acutely ischemic. More often, however, microemboli consisting of cholesterol crystals or clot obstruct small distal vessels, such as the digital arteries of the toes and arterioles and capillaries of the skin. These patients have livedo reticularis; one or more cool, painful, cyanotic toes; and palpable pedal pulses. This constellation of findings, often called the blue toe syndrome,28 is highly suggestive of a proximal source of emboli. When an AAA is the source, the aneurysm is often too small to palpate and may be discovered only after radiologic investigation.22,28

Rarely, an intact AAA causes symptoms by compressing adjacent structures, with symptoms depending on the structures involved. Large, long-standing aneurysms can cause vertebral body erosion and severe back pain. Compression of the duodenum between the superior mesenteric artery and an AAA can cause duodenal obstruction, vomiting, and weight loss.29 Obstruction of the ureters in the patient with an inflammatory aneurysm can cause symptoms suggestive of ureteral colic.23

Ruptured Aneurysms

The mechanism of the pain associated with aneurysm rupture is poorly understood. It may be caused by expansion of the aortic wall or by stimulation of sensory nerves in the retroperitoneum. Identical pain can occur with intact but acutely expanding aneurysms, which may be impossible to differentiate clinically from ruptured aneurysms.30,31 Acute pain in the patient with an AAA should be considered a symptom of rupture or impending rupture.

In patients with a ruptured aneurysm, the duration of symptoms before presentation varies greatly. Some patients are seen shortly after severe pain and hypotension develop. In others, rupture is initially contained in the retroperitoneum, blood loss is small, and the presentation is delayed. Rare patients with a ruptured AAA may have symptoms for several days or even weeks before seeking medical attention32; therefore a long duration of symptoms does not exclude the diagnosis of ruptured AAA.

Rupture of an AAA may be accompanied by nausea and vomiting, and sudden hemorrhage can cause syncope or near-syncope. Compensatory hemodynamic mechanisms may then return the blood pressure and cerebral perfusion to normal. Transient improvement in symptoms is common but will be followed by hemodynamic deterioration if diagnosis and treatment are delayed.33

Ruptured AAAs are often large, and most patients have palpable abdominal masses.34 As with intact aneurysms, a ruptured AAA may not be palpable if the aneurysm is small or the patient is obese. The examination may be difficult if abdominal guarding is present or if an ileus causes significant distention. Aortic pulsations may not be prominent if the blood pressure is low. When a mass is not palpable, the diagnosis may be delayed.

Hypotension is the least consistent part of the triad, occurring in approximately half of patients, and is often a late finding.33,34 When the initial blood loss is minor, vital signs are often normal. Patients with initially normal vital signs are more likely to be misdiagnosed33 and may quickly and unpredictably deteriorate and become hypotensive.

Occasionally, rupture into the retroperitoneum is sealed and contained for many weeks or months.32 When this occurs, patients develop abdominal or back pain, presumably at the time of aneurysm leakage, which subsequently diminishes or resolves completely. If the diagnosis is made, chronic rupture (organized hematoma) is found at surgery. These patients can have chronic pain and may progress to free rupture and massive hemorrhage at any time.32

Aortoenteric Fistula

An AAA can rupture into the gastrointestinal tract (aortoenteric fistula [AEF]) or inferior vena cava (aortocaval fistula). A primary AEF is formed when an unrepaired AAA erodes into the gastrointestinal tract,35 usually the third or fourth portion of the duodenum. A secondary AEF, a communication between the site of previous aortic surgery and the gastrointestinal tract,36,37 can occur as a late complication of AAA repair and should be considered as the leading diagnosis in any patient with a severe gastrointestinal bleed and a history of aortic graft placement.

The patient with an AEF may have abdominal or back pain, fever and other signs of intra-abdominal infection, or gastrointestinal bleeding. Because most of these fistulae are into the duodenum, hemorrhage usually manifests as hematemesis or melena. The initial bleeding results from erosion of vessels in the bowel wall and is often minor.37 Later, often after several days to a week or longer, massive bleeding results from rupture into the intestinal lumen.

Aortovenous (Aortocaval) Fistula

An aortovenous (usually aortocaval) fistula arises when periaortic inflammation causes adherence of the aorta to an adjacent vein, with pressure on the vessel walls causing the development of an arteriovenous communication. If concomitant extravasation of blood into the retroperitoneum occurs, the clinical presentation is similar to that of other patients with ruptured AAAs, often with hypovolemic shock. More commonly, however, the aneurysm ruptures into the vena cava without leaking externally, and the signs and symptoms of a large arteriovenous fistula dominate the clinical picture.27,38

As in other patients with AAAs, a patient with an aortovenous fistula may have abdominal or back pain. An aneurysm that becomes fistulous with the vena cava is usually large, and 80 to 90% are palpable. A continuous abdominal bruit can be auscultated in approximately 75% of patients with aortovenous fistulae, and 25% of patients have a palpable abdominal thrill.38

Shunting of blood from the arterial to the venous system increases venous pressure, venous volume, and venous return to the heart. Signs and symptoms of high-output congestive heart failure (dyspnea, jugular venous distention, pulmonary edema) are often present.38 The increased venous volume and pressure can cause lower extremity edema or cyanosis, and dilated superficial veins can be seen on the legs or abdominal wall. Distention and rupture of veins in the bladder mucosa can cause gross or microscopic hematuria; rectal bleeding can occur for similar reasons. Because of shunting of arterial blood into the venous system, the lower extremities may be cool with diminished pulses.

The patient with an aortovenous fistula often has renal insufficiency caused by a decrease in renal perfusion as a result of high-output congestive heart failure and increased renal venous pressure. Such patients may exhibit hematuria, which is common when an aortovenous fistula is present but not in other patients with AAAs.38 Computed tomography (CT; preferably CT angiography) can rule out aortovenous fistula formation.

Diagnostic Strategies

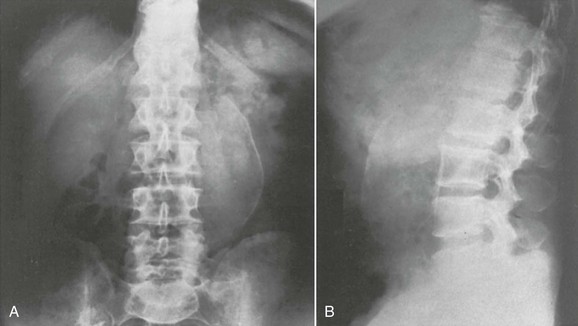

Plain film radiography is not indicated in the evaluation of a patient for suspected AAA. A normal plain abdominal radiograph does not exclude the presence of an AAA and rarely identifies alternative pathology. Even if an aneurysm is identified on plain film because it is calcified, imaging with CT is required to identify whether the aneurysm is an incidental or culprit lesion in the patient’s presentation (Fig. 86-2).

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography is virtually 100% sensitive in detecting AAAs (Fig. 86-3), when a technically adequate study can be obtained.1 Measurements of aortic diameter are very accurate and reproducible. Because it is relatively inexpensive and requires no contrast agents or radiation exposure, ultrasonography is used for nonemergency aneurysm diagnosis and to follow patients with known aneurysms.

Ultrasonography has distinct advantages in the emergency evaluation of a patient with a suspected ruptured AAA.39 It can be performed very rapidly at the patient’s bedside, obviating the need to take a potentially unstable patient to the radiology suite. If an aorta with a normal diameter throughout its abdominal course is visualized, the patient does not have an AAA. In addition, ultrasonography sometimes provides alternative explanations for the patient’s pain by revealing other conditions, such as acute cholecystitis.

However, ultrasonography has certain limitations. It is more operator dependent than other diagnostic modalities and may be prone to technical or interpretive error.40 Even more than with elective studies, in the emergency department the aorta may not be well visualized because of obesity or excess bowel gas.40–42 Ultrasonography is not immediately available in some EDs, requiring the patient to wait for the arrival of a technologist. Although ultrasonography is extremely sensitive in detecting an AAA, it cannot be relied on to reveal whether an AAA has ruptured.39

Free intraperitoneal or retroperitoneal blood, seen in the presence of an AAA, confirms a rupture.40 However, the sensitivity of emergency ultrasonography in detecting extraluminal blood is very low. The purpose of the study is to confirm or exclude the presence of an aneurysm; clinical information (or a CT scan) must be used to determine the likelihood of rupture. Ultrasonography with the use of contrast agents may aid in the detection of leaking blood,43 but the clinical usefulness of this modality remains to be determined. If ultrasonography reveals an AAA in an unstable patient, aneurysm rupture is presumed, and the patient requires immediate aneurysm repair.

Computed Tomography

The abdominal CT scan is the diagnostic test of choice in the evaluation of a patient with suspected ruptured AAA and is virtually 100% accurate in determining the presence or absence of an AAA and the presence of bleeding.40 CT also provides detailed anatomic information about the aneurysm.44,45

CT is much more sensitive than ultrasonography in detecting retroperitoneal hemorrhage associated with aneurysm rupture. The reported sensitivity approaches 100% with the use of current-generation scanning technology, with falsely negative studies sometimes occurring with very small ruptures. Blood is seen as a retroperitoneal fluid collection adjacent to the aneurysm, often tracking into the perinephric space or along the psoas muscle (Fig. 86-4).

Differential Considerations

Because the patient with a ruptured AAA usually has abdominal, back, or flank pain, with or without hypotension, common misdiagnoses are other disease processes that cause these symptoms (Box 86-1). The sudden onset of back pain often leads to the clinical suspicion of renal colic, with which AAA is often confused.33 Abdominal pain and tenderness can suggest pancreatitis, intestinal ischemia, or other intra-abdominal disorders. Musculoskeletal back pain is part of the differential diagnosis but should be confirmed by detailed history and physical examination, so that pain related to AAA is not mistakenly labeled as mechanical low back pain.

Ruptured AAA should be considered in middle-aged or elderly patients with any part of the classic triad. The diagnosis of ruptured AAA should also be considered in making the diagnoses listed in Box 86-1, especially when the diagnosis is not clear-cut or the patient is at risk for an AAA.

Management

The patient with a ruptured AAA is unstable until the aorta is cross-clamped in the operating room or stabilized with endovascular techniques. No patient with a known or suspected aortic rupture should be considered stable, regardless of the initial vital signs or initial hemoglobin level. Patients taken to the operating room soon after ED arrival have a much higher survival rate than those in whom surgical care is delayed.46

When the patient arrives at the ED, large-bore intravenous access should be established and blood sent for crossmatch. At least 6 units of blood should be made available initially, with notification to the blood bank of the potential need for significantly more, because patients with ruptured AAAs often have large transfusion requirements.47 The surgical and anesthesia team should be notified immediately. Further management depends on the current hemodynamic condition and the level of diagnostic certainty.

The hemodynamically unstable patient in whom a ruptured AAA has been diagnosed or is strongly suspected should be taken to the operating room as soon as possible (in this chapter, the term “operating room” includes other locations that may be used for endovascular aneurysm repair). Diagnostic testing should be kept to a minimum. The diagnosis can often be made from the clinical presentation and abdominal examination, and bedside ultrasonography can quickly confirm or exclude the presence of an aneurysm. A CT scan is appropriate only if it can be obtained very quickly without compromising the patient’s care. Time-consuming tests inappropriately delay definitive therapy and increase the risk of exsanguination. Hypotensive patients may have to be taken to the operating room based on a strong clinical presumption of the diagnosis, without definitive diagnostic imaging. Some of these patients will not have ruptured aneurysms, but they usually have other acute abdominal conditions requiring laparotomy.48

Fluid Resuscitation

The appropriate degree of preoperative volume resuscitation is controversial. Preoperative hypotension is the strongest predictor of mortality in the patient with a ruptured AAA.21,49 However, correction of the hypotension before the aorta is clamped may not improve mortality and may even be harmful.

It has been argued that hypotension slows bleeding in patients with AAA and allows local clot formation and tamponade of the rupture site. Raising the intravascular volume and blood pressure before occluding the aorta may dislodge clots and cause further bleeding.47,50,51 Large volumes of crystalloid solution may contribute to bleeding by causing a dilutional coagulopathy. These concerns are similar to those in trauma patients with uncontrolled hemorrhage.

No prospective studies have compared different preoperative fluid regimens in hypotensive patients with ruptured AAAs, and the optimal resuscitation strategy has not been determined. The priority in these patients is expeditious transportation to the operating room for definitive control of aortic hemorrhage. In the prehospital setting and in the ED before the surgeon and the operating room are available, the blood pressure should be raised with crystalloid or blood products to a level that maintains adequate cerebral and myocardial perfusion.50 The goal is to prevent irreversible end-organ damage. An arbitrary blood pressure goal cannot be specified because the blood pressure necessary for vital organ perfusion varies among patients, but a reasonable target is a systolic blood pressure of 90 to 100 mm Hg.

If blood products are to be administered in large amounts, fresh frozen plasma (FFP) and packed red blood cells (PRBCs) are beneficial in patients with ruptured AAAs.47 As with trauma patients, a PRBC : FFP ratio of less than 2 : 1 results in improved mortality.47

Diagnostic Confirmation

CT may provide confirmation of rupture, allowing the surgeon to avoid the complications of emergency surgery in a patient with an intact aneurysm. With emergency surgery, detailed anatomic evaluation and careful preoperative planning are often impossible, evaluation and optimization of the patient’s cardiopulmonary and renal function may be precluded, and invasive hemodynamic monitoring may be unavailable. For these reasons, patients who are taken for emergency surgery and are found to have intact, symptomatic aneurysms have a higher mortality rate than patients undergoing elective aneurysm repair.30,31,52

Surgery and Mortality

Ruptured AAA is uniformly fatal unless treated surgically. Thus once this diagnosis has been made, repair should be attempted in almost all patients. Attempts have been made to identify patients with a very low likelihood of survival, and it has been suggested that surgery can be withheld in patients with prehospital or ED cardiac arrest. However, no variables that can be assessed in the ED, including cardiac arrest, are universally predictive of a fatal outcome.21 Repair is indicated unless the patient’s life expectancy is very short because of underlying illnesses or the patient’s quality of life is so poor that repair is considered unreasonable. Hypotension is the most important factor predicting a poor outcome in patients undergoing surgery.21,47,49,50

Although patients with ruptured AAAs have a mortality of 30 to 40% with open repair,11,49,51,53 recent data suggest significantly lower mortality at centers experienced with the endovascular approach, with an operative mortality rate of 20 to 25%.51,54–57 Endovascular repair of ruptured aneurysms is becoming increasingly more common, even in unstable patients.54,58–60 If necessary, the surgeon can stabilize the patient by placing an aortic occlusion balloon above the aneurysm after rapidly accessing the femoral artery.

Not all patients with ruptured aneurysms will have an aorta that is anatomically suitable for endovascular repair.58,59 The method of repair will clearly be the surgeon’s decision. Planning for the care of such patients should include the development of a well understood protocol that advises the ED staff about which services to mobilize and which diagnostic tests to perform for patients with ruptured AAA.60

Unfortunately, even with the recent improvement in treatment outcomes, operative mortality rates significantly underestimate the true lethality of ruptured AAAs. The patient with a ruptured AAA may die at home or may reach the hospital but die before surgery. When patients who do not reach the operating room are considered, the overall mortality rate may be as high as 80%.61

Intact, Asymptomatic Aneurysms

In two clinical trials, one of which has long-term follow-up, patients with small (<5.5 cm) aneurysms were randomized to early surgery or close follow-up.62–64 In the latter group, aneurysms were followed with serial ultrasounds or CT scans, and surgery was performed only if symptoms developed, rapid expansion was documented, or a diameter of 5.5 cm was reached. Both studies showed equivalent survival rates in the two groups. As a result, fewer small aneurysms are now repaired electively, potentially leaving a larger group of patients who may come to the ED with complications of an AAA. It is important to note that the “watchful waiting” approach is appropriate only for asymptomatic aneurysms, and rupture of the AAA should be strongly considered in the evaluation of any symptoms in these patients.

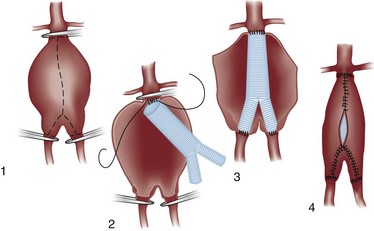

Traditional Repair

The conventional technique for repair of AAAs is an open approach with a laparotomy. The aneurysm is opened longitudinally and repaired from within (Fig. 86-5). A graft is inserted inside the aneurysm and anastomosed to uninvolved vessels above and below. When possible, a straight graft is used between the infrarenal and distal aorta, but if the aneurysm involves the aortic bifurcation or if iliac artery aneurysmal or occlusive disease is present, a bifurcation graft is used, with the distal anastomosis to the iliac or femoral arteries. The aneurysm wall is then closed around the graft to help separate it from adjacent structures.

Endovascular Repair

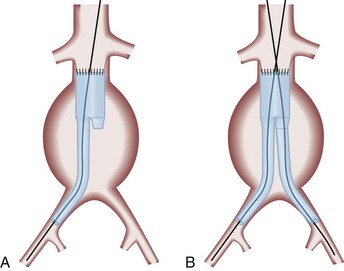

More than half of all AAA repairs are now performed without laparotomy, with use of endovascular techniques.44,45,65,66 A stent graft (a fabric graft supported by an internal wire frame) is placed into the femoral artery percutaneously or through a groin incision and is advanced under fluoroscopic guidance to a position that spans the aneurysm (Fig. 86-6A). The contralateral iliac limb is placed to form a bifurcated graft (Fig. 86-6B). Once in position, the graft is expanded to fit tightly against the walls of the aorta. Early straight (tube) grafts are now rarely used because of a high failure rate.

Endovascular surgery avoids the morbidity of a laparotomy and may allow the repair of AAAs in some high-risk patients who would not tolerate conventional surgery. Perioperative mortality is lower than that with open repair,65,67–69 but it is unclear whether this mortality benefit is sustained in the long-term.69,70 Endovascular repair requires more frequent reinterventions for graft-related complications.70 Because not all aneurysms are anatomically suitable for endovascular repair, detailed preoperative imaging and planning are required to make this determination.44,45 In addition, patients who have had endovascular aneurysm repair remain at risk for several complications, most importantly rupture of the aneurysm.45,70

Survival

The operative mortality rate for elective AAA repair is approximately 1 to 2% for endovascular repair and 3 to 5% for open repair,69,70 in contrast to the much higher operative mortality with ruptured aneurysms.51,53,54,71,72 Patients who survive the operation have an excellent prognosis, with a long-term survival close to that of the general population. After repair of the aneurysm, long-term survival is primarily limited by associated cardiac disease.

Late Complications of Repair

Graft infection, AEF formation, and anastomotic aneurysm (pseudoaneurysm) formation can occur at any time from weeks to many years after the surgery.36,73 These complications often occur together, their clinical presentations overlap, and they are diagnosed by similar means. In addition, endovascular aneurysm repair has several unique complications, the most important of which is endoleak.

Aortoenteric Fistula

If the patient with a suspected AEF is unstable with massive bleeding, diagnostic testing may be dangerously time-consuming. In these patients, emergency laparotomy may be necessary to control hemorrhage and diagnose or exclude the presence of an AEF.37 Stable patients can be evaluated with endoscopy or a CT scan. Some patients with AEF may be treated endovascularly, which may result in improved perioperative morbidity and mortality.37

An abdominal CT scan can also be used to evaluate a suspected AEF.36 Although imaging of the fistula may not be possible, graft infection is almost invariably present in patients with secondary AEFs, and the CT scan will demonstrate the associated infection. Radiographically distinguishing an AEF from intra-abdominal graft infection alone may be difficult, but the distinction is not crucial, as both need surgical management.

Complications of Endovascular Aneurysm Repair

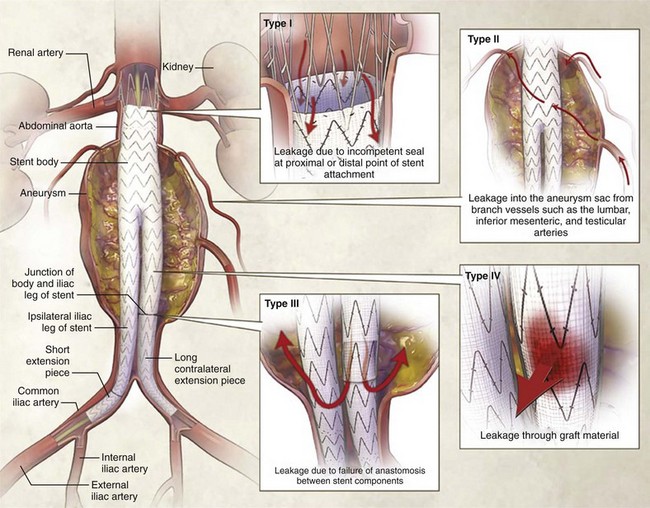

A rapidly increasing percentage of elective AAA repairs are done with endovascular techniques, and these patients may come to the ED with postoperative complications. The most serious of these is endoleak—blood flow outside of the graft lumen but within the aneurysm sac, potentially allowing enlargement of the aneurysm. Endoleaks may be caused by separation of the proximal or distal end of the graft from the aortic wall (type I), back-bleeding into the aneurysm sac from branch vessels such as lumbar arteries (type II), leakage between the modular components of the graft (type III), or leakage through the graft fabric itself (type IV) (Fig. 86-7).45,74 It is important to note that with persistent leakage of blood into the aneurysm sac, the patient is at risk for rupture of the aneurysm.44,45,70,74,75

Endoleaks may develop soon after the procedure or much later. They have been reported in as many as 20% of patients who have had endovascular aneurysm repair.74,76 Because many endoleaks resolve spontaneously, patients are sometimes observed for months before repair of the leak with secondary endovascular procedures or surgical intervention.

In the ED, CT with intravenous contrast should be used to evaluate for possible complications of endovascular repair.77 A specific CT imaging protocol may be desired; this should be discussed with the radiologist or vascular surgeon.

Disposition

A patient with an acutely symptomatic AAA requires hospital admission and urgent or emergency repair. A patient whose aneurysm is asymptomatic and discovered incidentally should be referred for consideration of elective repair. The patient with an AAA should be referred for an outpatient workup only if it is clear that the symptoms prompting the ED visit are unrelated to the aneurysm. Although the incidental detection of AAA is common, such patients may suffer from poor subsequent follow-up and monitoring.24 If the patient is discharged, appropriate referral for follow-up is crucial, and instructions should be given to seek immediate medical attention if abdominal, back, or flank pain develops.

References

1. Lederle, FA. Ultrasonographic screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:516–522.

2. Lederle, FA, et al. The aneurysm detection and management study screening program: Validation cohort and final results. Aneurysm Detection and Management Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Investigators. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1425–1430.

3. Ashton, HA, et al. The Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study (MASS) into the effect of abdominal aortic aneurysm screening on mortality in men: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1531–1539.

4. Norman, PE, et al. Population based randomised controlled trial on impact of screening on mortality from abdominal aortic aneurysm. BMJ. 2004;329:1259–1264.

5. Webster, MW, et al. Ultrasound screening of first-degree relatives of patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 1991;13:9–14.

6. Madaric, J, et al. Frequency of abdominal aortic aneurysm in patients >60 years of age with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:1214–1216.

7. Lindholt, JS, Sorensen, J, Sogaard, R, Henneberg, EW. Long-term benefit and cost-effective analysis of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms from a randomized controlled trial. Br J Surg. 2010;97:826–834.

8. Barba, A, Estallo, L, Rodríguez, L, Baquer, M, Vega de Céniga, M. Detection of abdominal aortic aneurysm in patients with peripheral artery disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005;30:504–508.

9. Larsson, E, Granath, F, Swedenborg, J, Hultgren, R. A population-based case-control study of the familial risk of abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:47–51.

10. Forsdahl, SH, Singh, K, Solberg, S, Jacobsen, BK. Risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysms: A 7-year prospective study: The Tromso Study, 1994-2001. Circulation. 2009;119:2202–2208.

11. Mureebe, L, et al. National trends in the repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:1101–1107.

12. Kent, KC, et al. Analysis of risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysm in a cohort of more than 3 million individuals. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:539–548.

13. Diehm, N, et al. Novel insight into the pathobiology of abdominal aortic aneurysm and potential future treatment concepts. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2007;50:209–217.

14. Brewster, DC, Cronenwett, JL, Hallett, JW. Guidelines for the treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Report of a subcommittee of the Joint Council of the American Association for Vascular Surgery and Society for Vascular Surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2003;37:1106–1117.

15. Lederle, FA, et al. Rupture rate of large abdominal aortic aneurysms in patients refusing or unfit for elective repair. JAMA. 2002;287:2968–2972.

16. Powell, JT, Greenhalgh, RM. Clinical practice: Small abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1895–1901.

17. Krupski, WC, Rutherford, RB. Update on open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms: The challenges for endovascular repair. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:946–960.

18. Thompson, AR, Cooper, JA, Ashton, HA, Hafez, H. Growth rates of small abdominal aortic aneurysms correlate with clinical events. Br J Surg. 2010;97:37–44.

19. Powell, JT, Brown, LC, Greenhalgh, RM, Thompson, SG. The rupture rate of large abdominal aortic aneurysms: Is this modified by anatomical suitability for endovascular repair? Ann Surg. 2008;247:173–179.

20. Noel, AA, et al. Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms: The excessive mortality rate of conventional repair. J Vasc Surg. 2001;34:41–46.

21. Alonso-Pérez, M, et al. Factors increasing the mortality rate for patients with ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms. Ann Vasc Surg. 2001;15:601–607.

22. Baxter, BT, et al. Distal embolization as a presenting symptom of aortic aneurysms. Am J Surg. 1990;160:197–201.

23. Yusuf, K, et al. Inflammatory abdominal aortic aneurysm: Predictors of long-term outcome in a case-control study. Surgery. 2007;141:83–89.

24. van Walraven, C, et al. Incidence, follow-up, and outcomes of incidental abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:282–289.

25. Lederle, FA, Simel, DL. Does this patient have abdominal aortic aneurysm? JAMA. 1999;281:77–82.

26. Fink, HA, et al. The accuracy of physical examination to detect abdominal aortic aneurysm. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:833–836.

27. Takaseya, T, et al. A case of unilateral leg edema due to abdominal aortic aneurysm with aortocaval fistula. Ann Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;13:135–138.

28. Karmody, AM, Powers, SR, Monaco, VJ, Leather, RP. “Blue toe” syndrome. An indication for limb salvage surgery. Arch Surg. 1976;111:1263–1268.

29. Deitch, JS, et al. Abdominal aortic aneurysm causing duodenal obstruction: Two case reports and review of the literature. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:543–547.

30. De Martino, RR, et al. Outcomes of symptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:5–12.

31. Soisalon-Soininen, S, Salo, JA, Perhoniemi, V, Mattila, S. Emergency surgery of non-ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 1999;88:38–43.

32. Sterpetti, AV, et al. Sealed rupture of abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 1990;11:430–435.

33. Gaughan, M, McIntosh, D, Brown, A, Laws, D. Emergency abdominal aortic aneurysm presenting without haemodynamic shock is associated with misdiagnosis and delay in appropriate clinical management. Emerg Med J. 2009;26:334–339.

34. Rose, J, Civil, I, Koelmeyer, T, Haydock, D, Adams, D. Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms: Clinical presentation in Auckland 1993-1997. ANZ J Surg. 2001;71:341–344.

35. Saers, SJ, Scheltinga, MR. Primary aortoenteric fistula. Br J Surg. 2005;92:143–152.

36. Armstrong, PA, et al. Improved outcomes in the recent management of secondary aortoenteric fistula. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42:660–666.

37. Baril, DT, et al. Evolving strategies for the treatment of aortoenteric fistulas. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44:250–257.

38. Cinara, IS, et al. Aorto-caval fistulas: A review of eighteen years experience. Acta Chir Belg. 2005;105:616–620.

39. Kuhn, M, et al. Emergency department ultrasound scanning for abdominal aortic aneurysm: Accessible, accurate, and advantageous. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;36:219–223.

40. Hermsen, K, Chong, WK. Ultrasound evaluation of abdominal aortic and iliac aneurysms and mesenteric ischemia. Radiol Clin North Am. 2004;42:365–381.

41. Hoffman, B, et al. Successful sonographic visualization of the abdominal aorta differs significantly among a diverse group of credentialed emergency department providers. Emerg Med J. 2010;28:472–476.

42. Blaivas, M, Theodoro, D. Frequency of incomplete abdominal aorta visualization by emergency department bedside ultrasound. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:103–105.

43. Catalano, O, Lobianco, R, Cusati, B, Siani, A. Contrast-enhanced sonography for diagnosis of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:423–427.

44. Brewster, DC, et al. Long-term outcomes after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: The first decade. Ann Surg. 2006;244:426–438.

45. Eliason, JL, Upchurch, GR, Jr. Endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Circulation. 2008;117:1738–1744.

46. Hans, SS, Huang, RR. Results of 101 ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm repairs from a single surgical practice. Arch Surg. 2003;138:898–901.

47. Mell, MW, et al. Effect of early plasma transfusion on mortality in patients with ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Surgery. 2010;148:955–962.

48. Valentine, RJ, Barth, MJ, Myers, SI, Clagett, GP. Nonvascular emergencies presenting as ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms. Surgery. 1993;113:286–289.

49. Verhoeven, EL, et al. Mortality of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm treated with open or endovascular repair. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:1396–1400.

50. Roberts, K, Revell, M, Youssef, H, Bradbury, AW, Adam, DJ. Hypotensive resuscitation in patients with ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2006;31:339–344.

51. Veith, FJ, et al. Collected world and single center experience with endovascular treatment of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms. Ann Surg. 2009;250:818–824.

52. Baxter, BT, Terrin, MC, Dalman, RL. Medical management of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Circulation. 2008;117:1883–1889.

53. Bown, MJ, Sutton, AJ, Bell, PR, Sayers, RD. A meta-analysis of 50 years of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Br J Surg. 2002;89:714–730.

54. McPhee, J, Eslami, MH, Arous, EJ, Messina, LM, Schanzer, A. Endovascular treatment of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms in the United States (2001-2006): A significant survival benefit is independently associated with increased institutional volume. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:817–826.

55. Davenport, DL, et al. Thirty-day NSQIP database outcomes of open versus endoluminal repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:305–309.

56. Rayt, HS, Sutton, AJ, London, NJ, Sayers, RD, Bown, MJ. A systematic review and meta-analysis of endovascular repair for ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;36:536–544.

57. Mayer, D, et al. 10 years of emergency endovascular aneurysm repair for ruptured abdominal aortoiliac aneurysms: Lessons learned. Ann Surg. 2009;249:510–515.

58. Najjar, SF, et al. Percutaneous endovascular repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms. Arch Surg. 2007;142:1049–1052.

59. Balm, R. Endovascular repair of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Br J Surg. 2008;95:133–134.

60. Mehta, M, et al. Establishing a protocol for endovascular treatment of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms: Outcomes of a prospective analysis. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44:1–8.

61. Adam, DJ, Mohan, IV, Stuart, WP, Bain, M, Bradbury, AW. Community and hospital outcome from ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm within the catchment area of a regional vascular surgical service. J Vasc Surg. 1999;30:922–928.

62. Lederle, FA, et al. Immediate repair compared with surveillance of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1437–1444.

63. United Kingdom Small Aneurysm Trial Participants. Long-term outcomes of immediate repair compared with surveillance of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1445–1452.

64. Powell, JT, et al. Final 12-year follow-up of surgery versus surveillance in the UK Small Aneurysm Trial. Br J Surg. 2007;94:702–708.

65. Schermerhorn, ML, et al. Endovascular vs. open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms in the Medicare population. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:464–774.

66. Landon, BE, O’Malley, AJ, Giles, K, Cotterill, P, Schermerhorn, ML. Volume-outcome relationships and abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Circulation. 2010;122:1290–1297.

67. Blankensteijn, JD, et al. Two-year outcomes after conventional or endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2398–2405.

68. Prinssen, M, et al. A randomized trial comparing conventional and endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1607–1618.

69. Lederle, FA, et al. Outcomes following endovascular vs. open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm: A randomized trial. JAMA. 2009;302:1535–1542.

70. United Kingdom EVAR Trial Investigators. Endovascular versus open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1863–1871.

71. Heller, JA, et al. Two decades of abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: Have we made any progress? J Vasc Surg. 2000;32:1091–1100.

72. Hoornweg, LL, et al. Meta analysis on mortality of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;35:558–570.

73. Hallett, JW, Jr., et al. Graft-related complications after abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: Reassurance from a 36-year population-based experience. J Vasc Surg. 1997;25:277–284.

74. Conrad, MF, et al. Secondary intervention after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Ann Surg. 2009;250:383–389.

75. Leurs, LJ, Buth, J, Laheij, RJ. Long-term results of endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm treatment with the first generation of commercially available stent grafts. Arch Surg. 2007;142:33–41.

76. van Marrewijk, C, et al. Significance of endoleaks after endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms: The EUROSTAR experience. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35:461–473.

77. Schmieder, GC, Stout, CL, Stokes, GK, Parent, FN, Panneton, JM. Endoleak after endovascular aneurysm repair: Duplex ultrasound imaging is better than computed tomography at determining the need for intervention. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:1012–1018.