Abdomen and gastrointestinal tract

6.1

Pneumoperitoneum

Radiological signs

1. Plain film (sensitivity 50–70%)

(a) Erect – free gas under diaphragm or liver. Can detect 10 ml of gas. Takes 10 minutes for all gas to rise.

(b) Supine – gas outlines both sides of bowel wall, which then appears as a white line. The most sensitive signs are in the right upper quadrant (often oval gas over the liver or a hyperlucent liver). In infants a large volume of gas will collect centrally, producing a rounded, relative translucency over the central abdomen. The falciform ligament may also be outlined by free gas.

2. CT (greater sensitivity than plain film) – suspected perforation

(a) Focal bowel wall thickening ± discontinuity in bowel wall.

(b) Extraluminal +ve oral contrast.

(i) Large volume – usually upper gastrointestinal tract, postendoscopy or secondary to obstruction.

(ii) Lesser sac – usually gastric or duodenal (rarely oesophagus or transverse colon).

(iii) Ligamentum teres – often gastric or duodenal.

(iv) Mesenteric folds – usually small bowel or colon (very rarely gastric).

(v) Retroperitoneal (duodenum ascending/descending colon, rectum, distal sigmoid).

Causes

(a) Peptic ulcer – 30% do not have free gas visible.

(b) Inflammation – diverticulitis, appendicitis, toxic megacolon, necrotizing enterocolitis.

2. Iatrogenic (surgery, peritoneal dialysis) – may take 3 weeks to reabsorb (faster in obese and children). Free gas may be seen on CT up to 14 days postsurgery.

3. Pneumomediastinum – see 4.30.

4. Introduction per vaginam – e.g. douching.

5. Pneumothorax – due to a congenital pleuroperitoneal fistula.

Chiu, Y. H., Chen, J. D., Tiu, C. M., et al. Reappraisal of radiographic signs of pneumoperitoneum at emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2009; 27(3):320–327.

Hainaux, B., Agneessens, E., Bertinotti, R., et al. Accuracy of MDCT in predicting site of gastrointestinal tract perforation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006; 187(5):1179–1183.

6.2

Gasless abdomen

6.3

Pharyngeal/oesophageal pouches and diverticula

Upper third

1. Zenker’s diverticulum – posteriorly, usually on left side, between the fibres of the inferior constrictor and cricopharyngeus. Can cause dysphagia, regurgitation, aspiration and hoarseness ± an air–fluid level.

2. Lateral pharyngeal pouch and diverticulum – through the unsupported thyrohyoid membrane in the anterolateral wall of the upper hypopharynx. Pouches are common and patients are usually asymptomatic. Diverticula are uncommon and are seen in patients with chronically elevated intrapharyngeal pressure, e.g. glass-blowers and trumpeters.

3. Lateral cervical oesophageal pouch and diverticulum – through the Killian–Jamieson space. Pouches are transient; diverticula are persistent. Patients are usually asymptomatic. The opening is below the level of cricopharyngeus.

Middle third

1. Traction – at level of carina. May be related to fibrosis after treatment for TB. Asymptomatic.

2. Developmental – failure to complete closure of tracheo-oesophageal communication.

3. Intramural – rare. Multiple, tiny flask-shaped outpouchings. 90% have associated strictures, mainly in the upper third of the oesophagus.

6.4

Oesophageal ulceration

In addition to ulceration there may be non-specific signs of oesophagitis:

1. Thickening of longitudinal folds (> 2 mm).

2. Thickening of transverse folds resembling small bowel mucosal folds.

Inflammatory

1. Reflux oesophagitis – ± hiatus hernia. Signs characteristic of reflux oesophagitis are:

(a) A gastric fundal fold crossing the gastro-oesophageal junction and ending as a polypoid protuberance in the distal oesophagus.

(b) Erosions – dots or linear streaks of barium in the distal oesophagus.

(c) Ulcers which may be round or, more commonly, linear or serpiginous.

2. Barrett’s oesophagus – to be considered in any patient with oesophageal ulceration or stricture but especially if the abnormality is in the body of the oesophagus (although strictures are more common in the lower oesophagus). Hiatus hernia in 75–90%. Usually endoscopic diagnosis.

3. Candida oesophagitis – predominantly in immunosuppressed patients. Early: small, plaque-like filling defects, often orientated in the long axis of the oesophagus. Advanced: cobblestone mucosal surface ± luminal narrowing. Ulceration is uncommon. Tiny bubbles along the top of the column of barium – the ‘foamy’ oesophagus. Patients with mucocutaneous candidiasis or oesophageal stasis due to achalasia, scleroderma, etc., may develop chronic infection which is characterized by a lacy or reticular appearance of the mucosa ± nodular filling defects.

4. Viral – herpes and CMV occurring mostly in immunocompromised patients. May manifest as discrete ulcers or ulcerated plaques, or mimic Candida oesophagitis. Discrete ulcers on an otherwise normal background mucosa are strongly suggestive of a viral aetiology.

5. Caustic ingestion – ulceration is most marked at the sites of anatomical hold-up and progresses to a long, smooth stricture.

6. Radiotherapy – ulceration is rare. Altered oesophageal motility is frequently the only abnormality.

7. Crohn’s disease* – aphthoid ulcers and, in advanced cases, undermining ulcers, intramural tracking and fistulae.

8. Drug-induced – due to prolonged contact with tetracycline, quinidine and potassium supplements.

Canon, C. L., Morgan, D. E., Einstein, D. M., et al. Surgical approach to gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: what the radiologist needs to know. Radiographics. 2005; 25(6):1485–1499.

Levine, M. S., Rubesin, S. E. Diseases of the esophagus: diagnosis with esophagography. Radiology. 2005; 237:414–427.

6.5

Oesophageal strictures – smooth

Inflammatory

1. Peptic – the stricture develops relatively late. Most frequently at the oesophagogastric junction and associated with reflux and a hiatus hernia. Less commonly, more proximal in the oesophagus and associated with heterotopic gastric mucosa (Barrett’s oesophagus). ± Ulceration.

2. Scleroderma* – reflux through a wide open cardia may produce stricture. Oesophagus is the commonest internal organ to be affected. Peristalsis is poor, cardia wide open and the oesophagus dilated (contains air in the resting state).

3. Corrosives – acute: oedema, spasm, ulceration and loss of mucosal pattern at ‘hold-up’ points (aortic arch and oesophagogastric junction). Strictures are typically long and symmetrical, may take several years to develop and are more likely to be produced by alkalis than acid.

4. Iatrogenic – prolonged use of a nasogastric tube. Stricture in distal oesophagus probably secondary to reflux. Also drugs e.g. bisphosphonates.

Neoplastic

1. Carcinoma – squamous carcinoma may infiltrate submucosally. The absence of a hiatus hernia and the presence of an extrinsic soft-tissue mass should differentiate it from a peptic stricture but a carcinoma arising around the cardia may predispose to reflux.

2. Mediastinal tumours – carcinoma of the bronchus and lymph nodes. Localized obstruction ± ulceration and an extrinsic soft-tissue mass.

3. Leiomyoma – narrowing due to a smooth, eccentric, polypoid mass. ± Central ulceration.

6.6

Oesophageal strictures – irregular

Neoplastic

1. Carcinoma – increased incidence in achalasia, Plummer–Vinson syndrome, Barrett’s oesophagus, coeliac disease, asbestosis, lye ingestion and tylosis. Mostly squamous carcinomas; adenocarcinoma becoming more common. Appearances include:

(a) Irregular filling defect – annular or eccentric.

3. Carcinosarcoma – big polypoid tumour ± pedunculated. Better prognosis than squamous carcinoma.

6.7

Tertiary contractions in the oesophagus

6.8

Stomach masses and filling defects

Primary malignant neoplasms

1. Carcinoma – most polypoidal carcinomas are 1–4 cm in diameter. (Any polyp > 2 cm in diameter must be considered to be malignant). Endoscopic US accurate in local staging for early disease. CT superior for more advanced disease.

2. Lymphoma* – 1–5% of gastric malignancy. Usually non-Hodgkin’s. May be ulcerative, infiltrative and/or polypoid. Often cannot be distinguished from carcinoma, but extension across the pylorus is suggestive of a lymphoma. MALT lymphoma is strongly associated with Helicobacter pylori infection. CT – marked hyopattenuating wall thickening; mean 3–5 cm. Whole stomach involved in 50%. Most (not all) have adjacent lymphadenopathy.

3. GIST – commonest in stomach but also small bowel, colon and mesentery. Variable size and malignant potential. Cell-surface marker (c-KIT) detectable by immunohistochemistry. Large tumours hyperenhancing and often heterogeneous on CT/MRI. Ulceration and fistulation common. 50% have metastasis at presentation (liver, peritoneum). May enlarge with treatment: reduced enhancement suggests response.

Polyps

1. Hyperplastic – accounts for 80–90% of gastric polyps. Usually multiple, small (< 1 cm in diameter) and occur randomly throughout stomach but predominantly affect body and fundus. Associated with chronic gastritis. Rarely can be very large (3–10 cm).

2. Adenomatous – usually solitary, 1–4 cm in diameter, sessile and occur in antrum. High incidence of malignant transformation, particularly if > 2 cm in size and carcinomas elsewhere in stomach (because of dysplastic epithelium). Associated with pernicious anaemia.

3. Hamartomatous – characteristically multiple, small and relatively spare the antrum. Occur in 30% of Peutz–Jeghers syndrome, 40% of familial polyposis coli and Gardner’s syndrome.

Submucosal neoplasms

Smooth, well-defined filling defect, with a re-entry angle.

1. Leiomyoma – many previously diagnosed would now be classified as GIST. Can be very large with a substantial exogastric component. Central ulceration and massive haematemesis may occur.

2. Lipoma – can change shape with position of patient and may be relatively mobile on palpation.

3. Neurofibroma – NB. Leiomyomas and lipomas are more common, even in patients with generalized neurofibromatosis.

4. Metastases – frequently ulcerate: ‘bull’s-eye’ lesion (q.v.). Usually melanoma, but bronchus, breast, lymphoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma and any adenocarcinoma may metastasize to stomach. Breast primary often produces a scirrhous reaction, indistinguishable from linitis plastica (q.v.).

Others

1. Nissen fundoplication – may mimic a distorted mass in the fundus.

2. Bezoar – ‘mass’ may be mobile. Tricho- (hair) or phyto- (vegetable matter).

3. Lymphoid hyperplasia – innumerable, 1–3 mm diameter, round nodules in the antrum or antrum and body. Association with H. pylori gastritis.

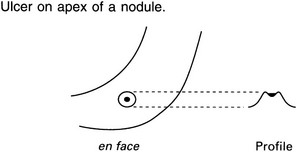

4. Pancreatic ‘rest’– ectopic pancreatic tissue causes a small filling defect, usually on the inferior wall of the antrum, and resembles a submucosal tumour. Central ‘blob’ of barium (‘bull’s-eye’ or target lesion) in 50%.

6.9

Thick stomach folds/wall

Inflammatory

1. Gastritis – localized or generalized fold thickening ± inflammatory nodules (< 1 cm, mostly in the antrum), erosions and coarse areae gastricae.

2. Zollinger–Ellison syndrome – suspect if postbulbar ulcers. Ulceration in both first and second parts of duodenum is suggestive, but ulceration distal to this is virtually diagnostic. Thick folds and small bowel dilatation may occur in response to excess acidity. Due to gastrinoma of non-beta cells of pancreas (no calcification, moderately vascular). 50% malignant – metastases to liver. (10% of gastrinomas may be ectopic – usually in medial wall of the duodenum.)

4. Crohn’s disease* – mild thickening of folds with aphthoid ulceration may occur in up to 40% of Crohn’s.

Infiltrative/neoplastic

1. Lymphoma* – usually non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, may be primary or secondary.

2. Carcinoma – irregular folds with rigid wall.

3. Pseudolymphoma – benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia. 70% have an ulcer near the centre of the area affected.

Others

1. Ménétrier’s disease – huge, smooth folds, especially greater curve. Rarely extend into antrum. No rigidity or ulcers. ‘Weep’ protein sufficient to cause hypoproteinaemia (effusions, oedema, thick folds in small bowel). Commonly achlorhydric: cf. Zollinger–Ellison syndrome.

2. Varices – occur in fundus and usually associated with oesophageal varices.

6.10

Linitis plastica

Inflammatory

1. Corrosives – can cause rigid stricture of antrum extending up to the pylorus.

2. Radiotherapy – can cause rigid stricture of antrum with some deformity. Mucosal folds may be thickened or effaced. Large antral ulcers can also occur.

3. Granulomata – Crohn’s disease, TB.

4. Eosinophilic enteritis – commonly involves gastric antrum (causing narrowing and nodules) in addition to small bowel. Blood eosinophilia. Occasionally spares the mucosa, so needs full-thickness biopsy for confirmation.

6.11

‘Bull’s-eye’ (target) lesion in the stomach

1. Submucosal metastases – may be multiple

3. Pancreatic ‘rest’ – ectopic pancreatic tissue. Usually on inferior wall of antrum. A central ‘blob’ of barium is seen in 50% – collects in primitive duct remnant. Can also occur in duodenum, jejunum, Meckel’s diverticulum, liver, gallbladder and spleen.

4. Neurofibroma – may be multiple. Other stigmata of neurofibromatosis.

6.13

Duodenal mural/fold thickening or mass

Neoplastic

1. Adenocarcinoma – 50–70% of small bowel carcinoma occurs in duodenum or proximal jejunum. Polypoidal mass or asymmetric wall thickening on CT. 50% have metastasis at presentation.

3. Brunner gland hamartoma – 10% of benign duodenal tumours. Usually D1. No malignant potential. 1–12 cm sessile or pedunculated filling defect.

4. Adenoma – malignant potential; associated with familial adenomatous polyposis.

5. GIST – unusual in duodenum; usually D2, D3; large size, heterogeneous rim enhancement and local invasion suggest malignant transformation.

7. Lymphoma – usually non-Hodgkin’s, T cell; CT-segmental non-obstructing mural thickening or extrinsic mass with or without aneurysmal dilatation.

8. Neuroendocrine tumour – 2–3% occur in duodenum; polypoidal or mass with rapid contrast enhancement and washout on CT.

Inflammatory/infiltrative

1. Duodenitis/ulcer – usually D1 related to H. pylori. Focal wall thickening and avid enhancement on CT. May see large ulcer cavity.

2. Crohn’s disease – mural thickening on CT/MRI ± layered contrast enhancement. Mild signs occur in duodenum in up to 40%, but severe involvement only occurs in 2%. D1 and D2 predominantly affected.

3. Cystic dystrophy – possible secondary to heterotopic pancreatic tissue in duodenal wall – D2. Presents with weight loss, pain and obstruction. Well-defined duodenal wall cysts on CT/MRI/US scan often with delayed mural enhancement due to fibrosis ± signs of chronic pancreatitis. Inflammatory changes in acute episode.

4. Groove pancreatitis – segmental inflammation between the head of pancreas and duodenum.

6. Diverticulum – up to 23%; may be large.

7. Duplication – less than 5% of intestinal duplications; thin-walled cyst on CT/MRI often with no luminal communication.

8. Infiltration – eosinophilic gastroenteritis, mastocytosis (dense bones), Whipple’s disease, amyloid.

10. Ischaemia – widespread changes can occur in vasculitis secondary to radiotherapy, collagen diseases and Henoch–Schönlein purpura.

6.14

Dilated small bowel

Calibre: proximal jejunum > 3.5 cm (4.5 cm if small bowel enema)

mid-small bowel > 3.0 cm (4.0 cm if small bowel enema)

ileum > 2.5 cm (3.0 cm if small bowel enema).

Normal folds

1. Mechanical obstruction – ± dilated large bowel, depending on level of obstruction. CT 78–100% sensitivity for high-grade obstruction (less in subacute). Small bowel faeces sign non-specific but may indicate point of obstruction.

2. Paralytic ileus – dilated small and large bowel.

3. Coeliac disease, dermatitis herpetiformis, tropical sprue – can produce identical signs. Dilatation is the hallmark, and correlates well with severity, but it is relatively uncommon. ± Dilution and flocculation of barium. See 6.16.

5. Iatrogenic – vagotomy and gastrectomy may produce dilatation due to rapid emptying of stomach contents. Dilatation may also occur proximal to a small bowel loop.

6.15

Strictures in the small bowel

1. Adhesions – angulation of bowel which is constant in site. Normal mucosal folds.

2. Crohn’s disease* – ± ulcers and altered mucosal pattern.

3. Ischaemia – ulcers are rare. Evolution is more rapid than Crohn’s ± long strictures.

4. Radiation enteritis – see 6.16.

(a) Lymphoma* – usually secondary to contiguous spread from lymph nodes. Primary disease may occur and is nearly always due to non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: although dilatation is typically seen in lymphoma, stricturing may also occur.

(b) Carcinoid – although the appendix is the commonest site, these rarely metastasize. Of those occurring in small bowel, 90% are in ileum (mostly distal 60 cm), and 30% are multifocal. A fibroblastic response to infiltration produces a stricture ± mass. It is the commonest primary malignancy of small bowel beyond the DJ flexure, but only 30% metastasize (more likely if > 2 cm diameter) or invade. Carcinoid syndrome only develops with liver metastases – see 6.21.

(c) Carcinoma – if duodenal lesions are included this is the most common primary malignancy of the small bowel and the duodenum is the most frequent site. Ileal lesions are rare (unless associated with Crohn’s disease). Short segment annular stricture with mucosal destruction, ulcerating or polypoidal lesion. High incidence of second primary tumours.

(d) Sarcoma – lymphosarcoma or leiomyosarcoma. Thick folds with an eccentric lumen. Leiomyosarcomas may present as a large mass displacing bowel loops with a large barium-filled cavity.

(e) Metastases – usual sites of origin are malignant melanoma, ovary, pancreas, stomach, colon, breast, lung and uterus. Rounded deformities of the bowel wall with flattened mucosal folds. In patients with gynaecological malignancies, duodenal or jejunal obstructions are most likely due to metastases; most radiation-induced strictures are in the ileum.

6.16

Thickened folds in non-dilated small bowel – smooth and regular

Vascular

Radiotherapy

1. Acute – thickening of valvulae conniventes and poor peristalsis. Ulceration is rare.

2. Chronic – latent period of up to 25 years. Most common signs are submucosal thickening of valvulae conniventes and/or mural thickening. Stenoses, adhesions, sinuses and fistulae may also occur. (The absence of ulceration, cobblestoning and asymmetry differentiate it from Crohn’s disease.) May show homogeneous or layered enhancement on contrast-enhanced CT.

Oedema

1. Adjacent inflammation – focal.

2. Hypoproteinaemia – e.g. nephrotic, cirrhosis, protein-losing enteropathy. Generalized.

3. Venous obstruction – e.g. cirrhosis, Budd–Chiari syndrome, constrictive pericarditis.

4. Lymphatic obstruction – e.g. lymphoma, retroperitoneal fibrosis, primary lymphangiectasia (child with leg oedema).

Early infiltration

1. Amyloidosis – gastrointestinal tract commonly involved. Primary amyloid tends to produce generalized thickening, whereas secondary amyloid produces focal lesions. Malabsorption is unusual.

2. Eosinophilic enteritis – focal or generalized. Gastric antrum frequently involved. No ulcers. Blood eosinophilia. Occasionally spares mucosa – therefore need full-thickness biopsy for diagnosis.

6.17

Thickened folds in non-dilated small bowel – irregular and distorted

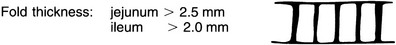

Normal fold thickness: jejunum < 2.5 mm; ileum < 2.0 mm.

Localized

Inflammatory

1. Crohn’s disease* – occurs before aphthoid ulcers.

2. Zollinger–Ellison syndrome – predominantly proximal small bowel. Dilatation may occur.

Levine, M. S., Rubesin, S. E., Laufer, I. Pattern approach for diseases of mesenteric small bowel on barium studies. Radiology. 2008; 249(2):445–460.

Maglinte, D. D., Kohli, M. D., Romano, S., Lappas, J. C. Air (CO2) double-contrast barium enteroclysis. Radiology. 2009; 252(3):633–641.

Maglinte, D. D., Sandrasegaran, K., Lappas, J. C. CT enteroclysis: techniques and applications. Radiol Clin North Am. 2007; 45(2):289–301.

6.18

Small bowel mural thickening on cross-sectional imaging – differentiation by contrast enhancement

Normal mural thickness: 1–2 mm (distended bowel); 3–4 mm (collapsed bowel).

6.19

Small bowel mural thickening on cross-sectional imaging – differentiation by length of involvement

Amzallag-Bellender, E., Oudjit, A., Ruiz, A., et al. Effectiveness of MR enterography for the assessment of small-bowel diseases beyond Crohn disease. Radiographics. 2012; 32(5):1423–1444.

Macari, M., Megibow, A. J., Balthazar, E. J. A pattern approach to the abnormal small bowel: observations at MDCT and CT enterography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007; 188:1344–1355.

6.20

Multiple nodules in the small bowel

Inflammatory

1. Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia – nodules 2–4 mm with normal fold thickness. Associated with hypogammaglobulinaemia (immunoglobulins A and M). Normal in children/adolescents. High incidence of intestinal infections (particularly giardiasis, but Strongyloides and Candida may also occur). Can also affect the colon.

2. Crohn’s disease* – cobblestone mucosa but other characteristic signs present.

Neoplastic

1. Lymphoma* – can produce diffuse nodules (2–4 mm) of varying sizes. Ulceration in the nodules is not uncommon.

(a) Peutz–Jeghers syndrome – AD. Buccal pigmentation. Multiple hamartomas (± intussusception) ‘carpeting’ the small bowel. Can also involve the colon (30%) and stomach (25%). Not in themselves premalignant, but associated with carcinoma of stomach, duodenum and ovary.

(b) Gardner’s syndrome – predominantly in the colon. Occasionally has adenomas in small bowel.

(c) Canada–Cronkhite syndrome – predominantly stomach and colon, but may affect the small bowel.

3. Metastases – on antimesenteric border. Particularly melanoma, breast, gastrointestinal tract and ovary. (Rarely bronchus and kidney.) ± Ascites.

6.21

Lesions in the terminal ileum

Inflammatory

2. Ulcerative colitis* – 10% of those with total colitis have ‘backwash’ ileitis for up to 25 cm, causing granular mucosa, ± dilatation. No ulcers.

3. Radiation enteritis – submucosal thickening of mucosal folds, mural thickening, symmetrical stenoses, adhesions, sinuses and fistulae. Ulceration and cobblestoning are not seen.

Infective

1. Tuberculosis – can look identical to Crohn’s disease. Continuity of involvement of caecum and ascending colon can occur. Longitudinal ulcers are uncommon. Less than 50% have pulmonary TB. Caecum is predominantly involved – progressive contraction of caecal wall opposite the ileocaecal valve, and cephalad retraction of the caecum with straightening of the ileocaecal angle.

2. Yersinia – cobblestone appearance and aphthoid ulcers. No deep ulcers and spontaneous resolution, usually within 10 weeks, distinguishes it from Crohn’s disease.

3. Actinomycosis – very rare. Predominantly caecum. ± Associated bone destruction with periosteal reaction. Occasionally pelvic bowel is secondarily involved from the gynaecological tract (especially with an intrauterine device).

Neoplastic

1. Lymphoma* – may look like Crohn’s disease.

2. Carcinoid – appendiceal carcinoid tumours are the most common and generally benign. Most ileal carcinoids originate in the distal ileum and are invariably malignant if > 2 cm. Radiological signs reflect the primary lesion (annular fibrotic stricture ± obstruction; intraluminal filling defect/enhancing mass), the mesenteric secondary mass (stretching of loops; rigidity and fixation), interference with the blood supply to the ileum by the secondary mass (thickening of mucosal folds) or the effects of fibrosis (sharp angulation of a loop; stellate arrangement of loops). The caecum may be involved and strictures may be multifocal.

6.22

Colonic polyps

Sensitivity of CT colonography superior to barium enema.

Adenomatous

1. Simple tubular adenoma, tubulovillous adenoma, villous adenoma – these three form a spectrum both in size and degree of dysplasia. Villous adenoma is the largest, shows the most severe dysplasia and has the highest incidence of malignancy. Signs suggestive of malignancy are:

Inflammatory

1. Ulcerative colitis* – polyps can be seen at all stages of activity of the colitis (no malignant potential): acute – pseudopolyps (i.e. mucosal hyperplasia); chronic – sessile polyp (resembles villous adenoma); quiescent – tubular/filiform (‘wormlike’) and can show a branching pattern. Dysplasia in colitic colons is usually not radiologically visible. When visible it appears as a solitary nodule, several separate nodules (both non-specific) or as a close grouping of multiple adjacent nodules with apposed, flattened edges (the latter appearance being associated with dysplasia in 50% of cases).

2. Crohn’s disease* – polyps less common than in ulcerative colitis.

6.23

Colonic strictures

Inflammatory

Tend to be symmetrical, smooth and tapered.

1. Ulcerative colitis* – usually requires extensive involvement for longer than 5 years. Commonest in sigmoid colon. May be multiple. Beware malignant complications – these are commonly irregular, annular strictures (30% are multiple). Risk factors are: total colitis, length of history (risk starts at 10 years and increases by 10% per decade), epithelial dysplasia on biopsy.

2. Crohn’s disease* – strictures occur in 25% of colonic Crohn’s disease, and 50% of these are multiple.

3. Pericolic abscess – can look malignant, but relative lack of mucosal destruction.

4. Radiotherapy – occurs several years after treatment. Commonest site is rectosigmoid colon, which appears smooth and narrow, and rises vertically out of pelvis due to thickening of surrounding tissue.

Infective

1. Tuberculosis – commonest in ileocaecal region. Short, ‘hour-glass’ stricture.

2. Amoeboma – more common in descending colon. Occurs in 2–8% of amoebiasis and is multiple in 50%. Rapid improvement after treatment with metronidazole.

3. Schistosomiasis – commonly rectosigmoid region. Granulation tissue forming after the acute stage (oedema, fold-thickening and polyps) may cause a stricture.

4. Lymphogranuloma venereum – sexually transmitted Chlamydia. Late complications are strictures which are characteristically long and tubular, and affect the rectosigmoid region. Fistulae may occur.

6.24

Colitis on cross-sectional imaging

Signs of inflammatory colitis on CT/MRI are often non-specific. The following is a guide only.

Diffuse

4. Pseudomembranous colitis – Clostridium difficile toxin. Very marked colon wall thickening (mean 15 mm) with thumbprinting. Pericolic stranding. Accordion sign (trapping of contrast between folds – also seen in ischaemia, cirrhosis and infectious types of colitis). Ascites in up to 35% (unlike Crohn’s disease). Often left-sided but may be segmental.

Predominantly right-sided

1. Crohn’s disease – skip lesions, mural thickening often greater than in UC (mean 11 mm vs 8 mm) lymphadenopathy.

3. TB – ileocaecal valve often involved. Distal colon can be involved, lymphadenopathy (low attenuation), sinuses, strictures. Ascites/peritoneal thickening may be present. No fibrofatty infiltration (cf. Crohn’s disease).

5. Amoebiasis – usually starts on the right but may be diffuse. Terminal ileum often spared. May produce toxic megacolon. Mass like amoebomas in 10%. Liver abscess.

6. Neutropenic enterocolitis (typhlitis) – immunosuppressive states (including AIDS). Marked thickening of right colon and terminal ileum. Pericolic stranding and fluid.

7. Ischaemic colitis – hyopvolaemic states in young patients. Cocaine users.

Predominantly left-sided

2. Ischaemic colitis – watershed areas in the sigmoid colon near the rectosigmoid junction and splenic flexure (especially the elderly). Rectum usually (but not always) spared.

3. Diverticulitis – may be right-sided but this is uncommon. Differentiation from cancer not always possible. Features suggesting diverticulitis: > 10 cm involvement, pericolonic stranding, engorged mesenteric vessels, fluid in the mesentery. Features suggesting cancer: focal concentric mass, shouldering, pericolonic nodes.

8. Epiploic appendagitis – often left-sided but can occur anywhere. Well-defined oval or round area of fat with an enhancing rim located immediately adjacent to the colon. High-density central focus.

6.25

Pneumatosis intestinalis (gas in the bowel wall)

Gas in the bowel wall. CT sensitivity much greater than plain films.

Benign causes

1. Idiopathic – up to 15% of cases and usually involves the colon; pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis.

2. Pulmonary – asthma, emphysema, PEEP, cystic fibrosis.

3. Intestinal – pyloric stenosis, intestinal pseudo-obstruction, enteritis, bowel obstruction, adynamic ileus, inflammatory bowel disease, leukaemia, collagen vascular disease (e.g. scleroderma).

4. Iatrogenic – barium enema/CT colonography, jejunostomy tubes, postsurgical anastomosis, endoscopy.

6.26

Megacolon in an adult

Non-toxic (without mucosal abnormalities)

1. Distal obstruction – e.g. carcinoma.

2. Ileus – paralytic or secondary to electrolyte imbalance.

3. Pseudo-obstruction – symptoms and signs of large bowel obstruction but with no organic lesion identifiable by barium enema or CT. A continuous, gas-filled colon with sharp, thin bowel wall, few fluid levels and gas or faeces in the rectum may differentiate from organic obstruction. Mortality is 25–30% and the risk of caecal necrosis and perforation is up to 15%.

6.28

Aphthoid ulcers

6.29

CT signs of intestinal ischaemia

Approximately 40% arterial emboli, 50% arterial thrombus, 10% venous occlusion.

1. Vascular occlusion – CT around 60% sensitive.

3. Hyperenhancement – occurs early: may indicate reversibility; or reperfusion.

4. Reduced enhancement – with or without target sign.

5. Mural thickening – more marked with venous infarction.

6. Mesenteric hyperattenuation – 30–70%, especially venous infarction.

6.30

Cross-sectional imaging signs of appendicitis

6.31

Causes of increased mesenteric attenuation – ‘misty mesentery’

Idiopathic

Mesenteric panniculitis (retractile/sclerosing mesenteritis)

(a) Idiopathic condition characterized by fat necrosis, inflammation (notably lymphocytic) and variable fibrosis. Associated with idiopathic inflammatory disorders (retroperitoneal fibrosis, sclerosing cholangitis, etc.). Link with neoplasia controversial but reported association with malignancy in up to 50% of cases (particularly lymphoma).

(b) CT features include increased mesenteric attenuation often with pseudocapsule (50–60%), surrounds but does not displace vessels (unlike liposarcoma) but may displace bowel loops. Discrete soft-tissue nodules may be apparent in 80%. Lymph nodes > 1 cm atypical (raises possibility of lymphoma). May progress to dense fibrosis (sclerosing mesenteritis).

6.32

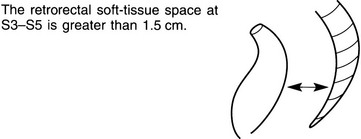

Widening of the retrorectal space/presacral mass

Inflammatory

1. Ulcerative colitis* – seen in 50% of these patients. Width increases as the disease progresses.

2. Crohn’s disease* – widening may diminish during the course of the disease.

Dahan, H., Arrive, L., Wendum, D., et al. Retrorectal developmental cysts in adults: clinical and radiologic–histopathologic review, differential diagnosis, and treatment. Radiographics. 2001; 21:575–584.

Shanbhogue, A. K., Fasih, N., Macdonald, D. B., et al. Uncommon primary pelvic retroperitoneal masses in adults: a pattern-based imaging approach. Radiographics. 2012; 32(3):795–817.

6.33

CT of a retroperitoneal cystic mass

6.35

Scintigraphic localization of gastrointestinal bleeding

Common sites

Alternatives to scintigraphy

1. Multidetector CT angiography – precontrast, aorta-triggered CT and delayed scans. Extravasation of intravenous contrast into the bowel lumen is diagnostic of gastrointestinal bleeding. Can detect a bleeding rate of more than 0.3 ml/minute.

2. Conventional angiography – can detect a bleeding rate of more than 0.5 ml/minute.

Geffroy, Y., Rodallec, M. H., Boulay-Coletta, I., et al. Multidetector CT angiography in acute gastrointestinal bleeding: why, when and how. Radiographics. 2011; 31(3):E35–E46.

Middleton, M. L., Strober, M. D. Planar scintigraphic imaging of the gastrointestinal tract in clinical practice. Semin Nucl Med. 2012; 42(1):33–40.

6.36

Causes of non-malignant fdg uptake in abdominal pet CT

6.37

Abdominal malignancy with poor fdg pet avidity

1. Hepatoma – up to 50% show no uptake.

2. Lymphoma subtypes – e.g. MALT.

3. Necrotic and metastatic mucinous adenocarcinoma.

4. Renal cell carcinoma – around 60% sensitivity.

5. Early-stage pancreatic cancer.

6. Prostate cancer – but may take up choline.

7. Neuroendocrine tumours – e.g. carcinoid: gallium-based tracers such as DOTATOC are useful.