Lumbar Puncture (Assist)

A lumbar puncture is performed for access to the subarachnoid space to obtain a cerebrospinal fluid sample, measure cerebrospinal fluid pressure, drain cerebrospinal fluid, infuse medications or contrast agents, or place a cerebrospinal fluid drainage catheter.1–3,7

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• Knowledge of neuroanatomy and physiology is needed.

• A lumbar puncture (LP) at L3-L4 or L4-L5 in an adult is usually performed to obtain a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sample.18

• Indications for lumbar puncture are as follows:

Cerebrospinal fluid analysis may be indicated in the differential diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage, central nervous system (CNS) infection, CNS autoimmune processes, and some malignant diseases.4,5,18,28

Cerebrospinal fluid analysis may be indicated in the differential diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage, central nervous system (CNS) infection, CNS autoimmune processes, and some malignant diseases.4,5,18,28

Therapeutically, a lumbar puncture may be used to treat hydrocephalus, cerebrospinal fluid fistulas, and pseudotumor cerebri; to deliver medications or contrast material into the subarachnoid space; or to access the subarachnoid space for placement of a lumbar subarachnoid drain.4,5,18,28

Therapeutically, a lumbar puncture may be used to treat hydrocephalus, cerebrospinal fluid fistulas, and pseudotumor cerebri; to deliver medications or contrast material into the subarachnoid space; or to access the subarachnoid space for placement of a lumbar subarachnoid drain.4,5,18,28

• Contraindications for lumbar punctures are as follows5,18,28,29:

Lumbar punctures are contraindicated if the patient has a known or suspected intracranial mass or elevated intracranial pressure (ICP), noncommunicating hydrocephalus, or infection in the region to be used for lumbar puncture or is coagulopathic or therapeutically anticoagulated. If CSF analysis is necessary, the patient may need pretreatment with fresh frozen plasma, platelets, cryoprecipitate, or the specific factor needed to correct a hematologic abnormality.5,18,28,29

Lumbar punctures are contraindicated if the patient has a known or suspected intracranial mass or elevated intracranial pressure (ICP), noncommunicating hydrocephalus, or infection in the region to be used for lumbar puncture or is coagulopathic or therapeutically anticoagulated. If CSF analysis is necessary, the patient may need pretreatment with fresh frozen plasma, platelets, cryoprecipitate, or the specific factor needed to correct a hematologic abnormality.5,18,28,29

Lumbar punctures are cautioned against in patients suspected of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage and in patients with complete spinal blocks. In such cases, a lumbar puncture may be performed if the computed tomographic (CT) scan of the patient’s head does not indicate signs of increased ICP, such as significant cerebral swelling, hematoma, intracranial tissue shifts, or herniation.5,18,28,29

Lumbar punctures are cautioned against in patients suspected of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage and in patients with complete spinal blocks. In such cases, a lumbar puncture may be performed if the computed tomographic (CT) scan of the patient’s head does not indicate signs of increased ICP, such as significant cerebral swelling, hematoma, intracranial tissue shifts, or herniation.5,18,28,29

Brain herniation may occur after punctures in the presence of an intracranial mass lesion or increased ICP.3,18

Brain herniation may occur after punctures in the presence of an intracranial mass lesion or increased ICP.3,18

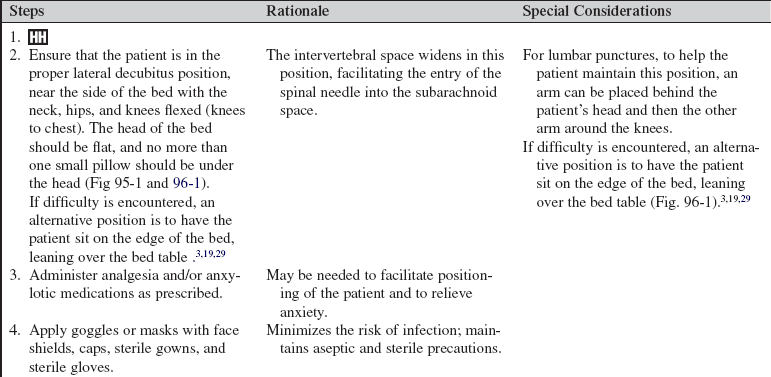

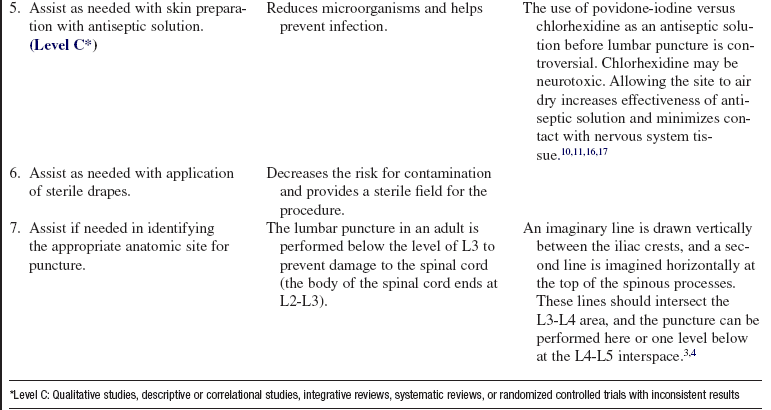

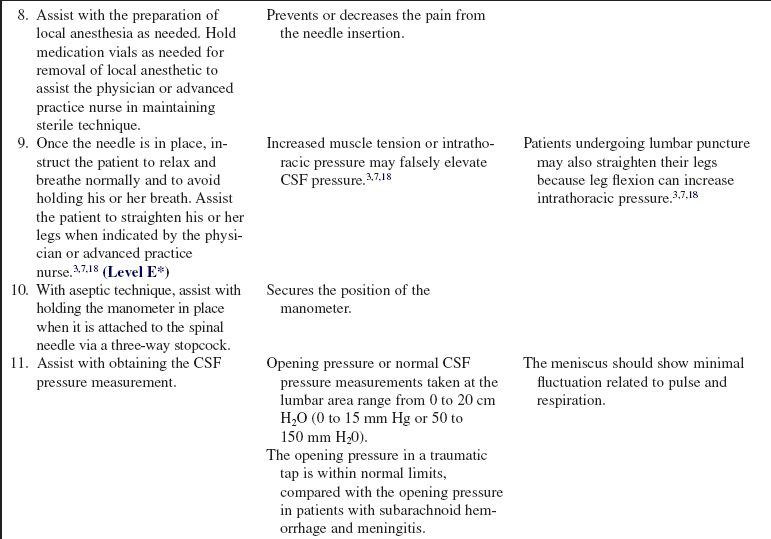

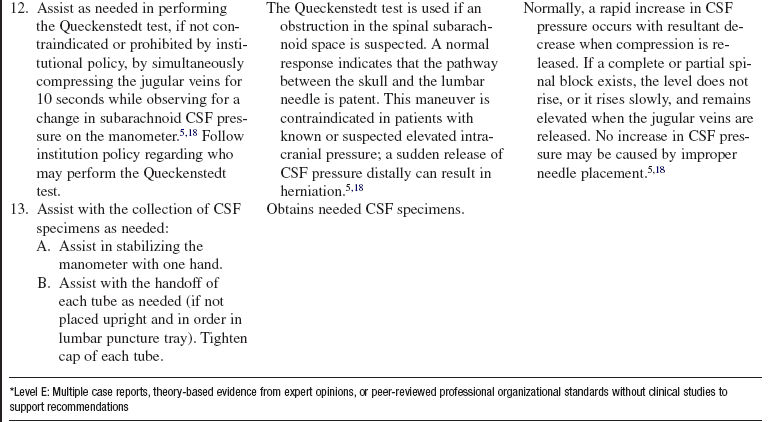

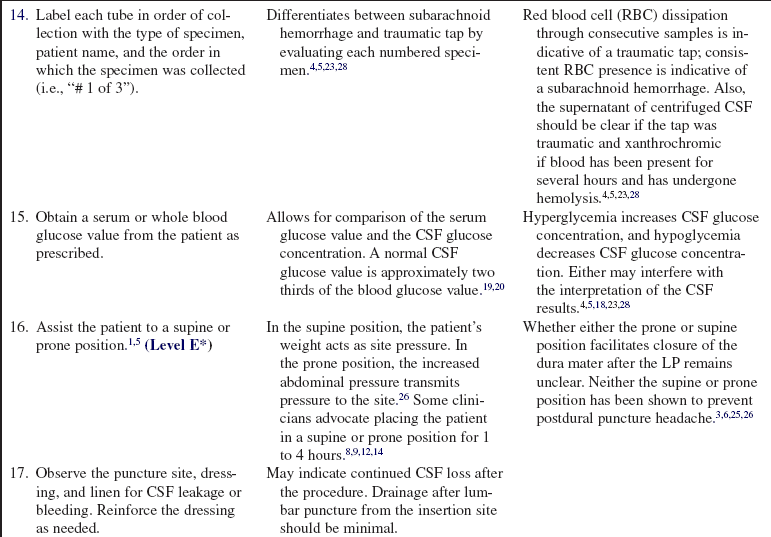

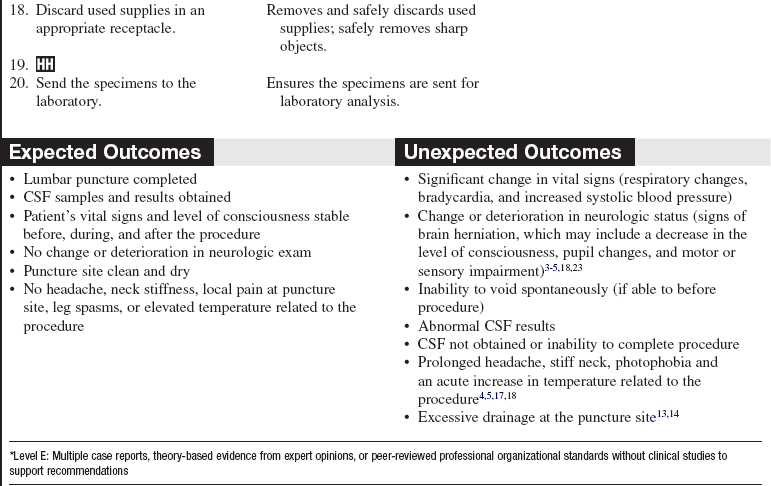

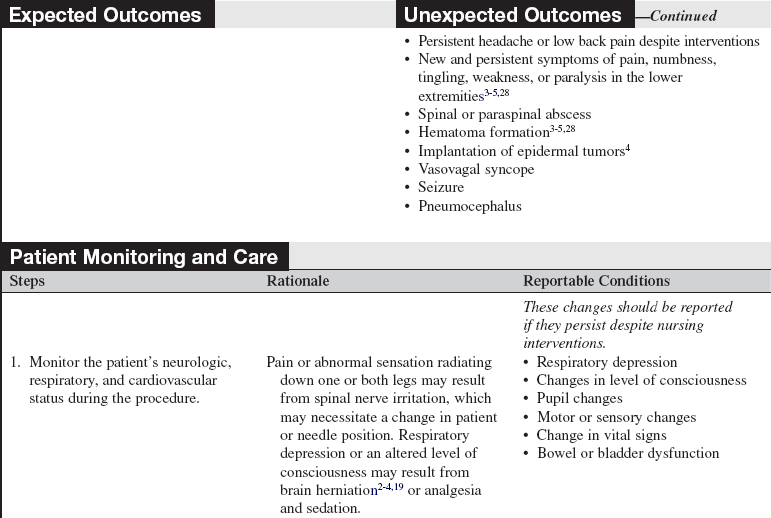

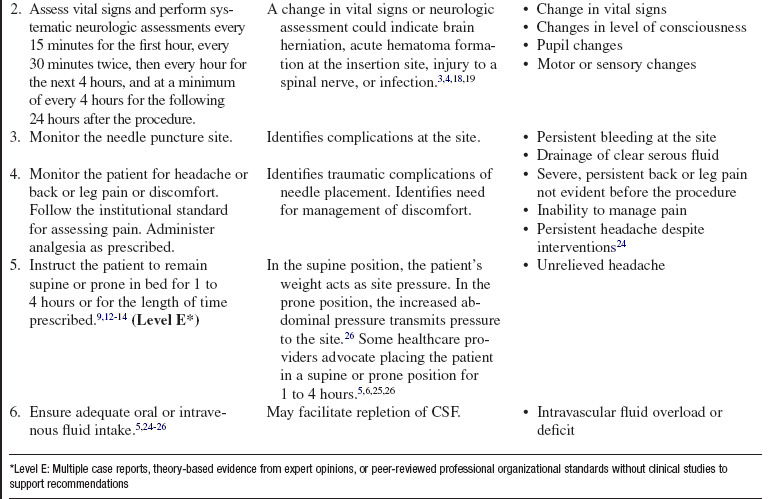

• The preferred positioning for a lumbar puncture is lateral decubitus with the neck, hips, and knees flexed (knees to chest); the axis of the hips vertical; the back close to the edge of the bed; head of the bed flat; and no more than a small pillow under the head (see Figs. 95-1 and 96-1).19 If the lumbar puncture is not successful in this position, or if the patient cannot tolerate this position, the patient may also be positioned sitting on the side of the bed, leaning over a bedside table or stand.19,21,23,29 This procedure may also be performed with fluoroscopy for patients with marked obesity or spinal deformities. Optimal positioning is necessary to avoid the risk for a “dry tap” or an unsuccessful puncture attempt. Repeated attempts at puncture increase the risk for infection and patient discomfort.3,18

• Proper positioning for a lumbar puncture widens the interspinous process space and facilitates the passage of the needle.2,3,5,6

EQUIPMENT

• Sterile gloves, caps, masks with eye shield, and sterile gowns

• Manometer with a three-way stopcock

• Lidocaine, 1% to 2% (without epinephrine)

• 18-, 20-, 22-, and 25-gauge needles

• 18-, 20-, or 22-gauge spinal needles

• Four consecutively numbered, capped test tubes

• Adhesive strip or sterile dressing supplies

• Glucometer/phlebotomy supplies for concurrent testing of serum or whole blood glucose

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the purpose of the procedure to the patient and family.  Rationale: Understanding of the procedure is reinforced, and anxiety may be decreased.

Rationale: Understanding of the procedure is reinforced, and anxiety may be decreased.

• Explain positioning requirements for the lumbar puncture.  Rationale: Cooperation with positioning requirements facilitates the procedure.

Rationale: Cooperation with positioning requirements facilitates the procedure.

• Explain that the procedure may cause some mild discomfort; the patient will receive local anesthesia and may also receive some mild analgesia and an anxiolytic.  Rationale: This prepares the patient for what to expect.

Rationale: This prepares the patient for what to expect.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Obtain vital signs.  Rationale: Baseline values for the patient are established.

Rationale: Baseline values for the patient are established.

• Perform a neurologic assessment, including level of consciousness, pupil size and reactivity, and motor and sensory function.  Rationale: Baseline neurologic function is established before the insertion of a needle into the proximity of sensitive neurologic tissue.

Rationale: Baseline neurologic function is established before the insertion of a needle into the proximity of sensitive neurologic tissue.

• Assess for signs and symptoms of increased ICP.  Rationale: Increased ICP during the LP may place the patient at risk for a downward shift in intracranial contents (brain herniation) when the pressure is suddenly released from the lumbar subarachnoid space.

Rationale: Increased ICP during the LP may place the patient at risk for a downward shift in intracranial contents (brain herniation) when the pressure is suddenly released from the lumbar subarachnoid space.

• Assess the patient’s current laboratory profile, including complete blood cell count, platelets, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, bleeding time, and international normalized ratio.  Rationale: Baseline values are established, and any coagulopathies that necessitate intervention before the cisternal or lumbar puncture are identified.

Rationale: Baseline values are established, and any coagulopathies that necessitate intervention before the cisternal or lumbar puncture are identified.

• Assess for signs and symptoms of meningeal irritation, including the following:

Brudzinski’s sign (flexion of the knee in response to flexion of the neck)

Brudzinski’s sign (flexion of the knee in response to flexion of the neck)

Kernig’s sign (pain in the hamstrings on extension of the knee with the hip at 90-degree flexion)

Kernig’s sign (pain in the hamstrings on extension of the knee with the hip at 90-degree flexion)

•  Rationale: Baseline neurologic function is established before introduction of a needle into the subarachnoid space.

Rationale: Baseline neurologic function is established before introduction of a needle into the subarachnoid space.

• Assess for allergies to local anesthetic, antiseptic, and any analgesic or sedative medications.  Rationale: Risk of allergic reaction is decreased.2–5

Rationale: Risk of allergic reaction is decreased.2–5

Patient Preparation

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Ensure that the patient and family understand preprocedural teaching. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

• Ensure that informed consent is obtained.  Rationale: Informed consent protects the rights of the patient and makes competent decision making possible for the patient; however, in emergency circumstances, time may not allow for the consent form to be signed.

Rationale: Informed consent protects the rights of the patient and makes competent decision making possible for the patient; however, in emergency circumstances, time may not allow for the consent form to be signed.

• Perform a pre-procedure verification and time out, if non-emergent.  Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

References

1. Ahmed, SV, Jayawarna, C, Jude, E, Post-lumbar puncture headache. diagnosis and management. Postgrad Med J 2006; 82:713–716.

Armon, C, Evans, RW, Addendum to assessment. prevention of post-lumbar puncture headachesreport of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2005; 65:510–512.

![]() 3. Boon, JM, Abrahams, PH, Meiring, JH, et al, Lumbar puncture. anatomical review of a clinical skill. Clin Anat 2004; 17:544–553.

3. Boon, JM, Abrahams, PH, Meiring, JH, et al, Lumbar puncture. anatomical review of a clinical skill. Clin Anat 2004; 17:544–553.

4. Ellenby, MS, Tegtmeyer, K, Lai, S, et al. Lumbar puncture. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355:e12.

![]() 5. Euerle, B. Spinal puncture and cerebrospinal fluid examination. In: Roberts JR, Hedges JR, Chanmugam AS, eds. Clinical procedures in emergency medicine. ed 4. St Louis: Elsevier; 2003:1197–1222.

5. Euerle, B. Spinal puncture and cerebrospinal fluid examination. In: Roberts JR, Hedges JR, Chanmugam AS, eds. Clinical procedures in emergency medicine. ed 4. St Louis: Elsevier; 2003:1197–1222.

![]() 6. Evans, RW, Armon, C, Frohman, EM, et al, Assessment. prevention of post-lumbar puncture headachesreport of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2000; 55:909–914.

6. Evans, RW, Armon, C, Frohman, EM, et al, Assessment. prevention of post-lumbar puncture headachesreport of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2000; 55:909–914.

7. Farley, A, McLafferty, E. Lumbar puncture. Nurs Stand. 2008; 22:46–48.

8. Frank, RL, Lumbar puncture and post-dural puncture headaches. implications for the emergency physician. J Emerg Med 2008; 35:149–157.

9. Gaiser, R. Postdural puncture headache. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2006; 19:249–253.

10. Hebl, JR. The importance and implications of aseptic techniques during regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2006; 31:311–323.

![]() 11. Kinirons, B, Mimoz, O, Lafendi, L, et al. Chlorhexidine versus povidone iodine in preventing colonization of continuous epidural catheters in children. Anesthesiology. 2001; 94:239–244.

11. Kinirons, B, Mimoz, O, Lafendi, L, et al. Chlorhexidine versus povidone iodine in preventing colonization of continuous epidural catheters in children. Anesthesiology. 2001; 94:239–244.

![]() 12. Levine, DN, Rapalino, O. The pathophysiology of lumbar puncture headache. J Neurol Sci. 2001; 192:1–8.

12. Levine, DN, Rapalino, O. The pathophysiology of lumbar puncture headache. J Neurol Sci. 2001; 192:1–8.

13. Lowery, S, Oliver, A. Incidence of postdural puncture headache and backache following diagnostic/therapeutic lumbar puncture using a 22G cutting spinal needle, and after introduction of a 25G pencil point spinal needle. Paediatr Anaesth. 2008; 18:230–234.

![]() 14. Luostarinen, L, Heinonen, T, Luostarinen, M, et al, Diagnostic lumbar puncture. comparative study between 22-gauge pencil point and sharp bevel needle. J Headache Pain 2005; 6:400–404.

14. Luostarinen, L, Heinonen, T, Luostarinen, M, et al, Diagnostic lumbar puncture. comparative study between 22-gauge pencil point and sharp bevel needle. J Headache Pain 2005; 6:400–404.

![]() 15. Manthous, CA, DeGirolamo, A, Haddad, C, et al, Informed consent for medical procedures. local and national practices. Chest 2003; 124:1978–1984.

15. Manthous, CA, DeGirolamo, A, Haddad, C, et al, Informed consent for medical procedures. local and national practices. Chest 2003; 124:1978–1984.

16. Milstone, AM, Passaretti, CL, Perl, TM, Chlorhexidine. expanding the armamentarium for infection control and prevention. Clin Infec Dis 2008; 46:274–281.

17. Reynolds, F. Neurological infections after neuraxial anesthesia. Anesthesiol Clin. 2008; 26:23–52.

![]() 18. Roos, KL. Lumbar puncture. Semin Neurol. 2003; 23:105–114.

18. Roos, KL. Lumbar puncture. Semin Neurol. 2003; 23:105–114.

19. Ropper, AH, Samuel, MA, Special techniques for neurological diagnosis. Adams and Victor’s principles of neurology. ed 9. McGraw-Hill, New York, 2009.

![]() 20. Seehusen, DA, Reeves, MM, Fomin, DA. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis. Am Fam Physician. 2003; 68:1103–1108.

20. Seehusen, DA, Reeves, MM, Fomin, DA. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis. Am Fam Physician. 2003; 68:1103–1108.

21. Shah, KH, McGillicuddy, D, Spear, J, et al. Predicting difficult and traumatic lumbar punctures. Am J Emerg Med. 2007; 25:608–611.

22. Stiffler, KA, Jwayyed, S, Wilber, ST, et al. The use of ultrasound to identify pertinent landmarks for lumbar puncture. Am J Emerg Med. 2007; 25:331–334.

23. Straus, SE, Thorpe, KE, Holroyd-Leduc J. How do I perform a a lumbar puncture and analyze the results to diagnose bacterial meningitis. JAMA. 2006; 296:2012–2022.

![]() 24. Sudlow, CL, Warlow, CC. Epidural blood patching for preventing and treating post-dural puncture headache. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2002. [CD001791].

24. Sudlow, CL, Warlow, CC. Epidural blood patching for preventing and treating post-dural puncture headache. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2002. [CD001791].

![]() 25. Sudlow, CL, Warlow, CC. Posture and fluids for preventing post-dural puncture headache. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2002. [CD001790].

25. Sudlow, CL, Warlow, CC. Posture and fluids for preventing post-dural puncture headache. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2002. [CD001790].

![]() 26. Turnbull, DK, Shepherd, DB, Post-dural puncture headache. pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment. Br J Anaesth 2003; 91:718–729.

26. Turnbull, DK, Shepherd, DB, Post-dural puncture headache. pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment. Br J Anaesth 2003; 91:718–729.

27. van Kooten F, Oedit, R, Bakker, SL, et al, Epidural blood patch in post dural puncture headache. a randomised, observer-blind, controlled clinical trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008; 79:553–558.

28. Weaver, JP. Cerebrospinal fluid aspirationIrwin RS, Rippe JM, eds.. Irwin and Rippe’s intensive care medicine. ed 6. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2008:151–158.

29. Williams, J, Lye, DCB, Umapathi, T, Diagnostic lumbar puncture. minimizing complications. Intern Med J 2008; 38:587–591.

Allen, SH. How to perform lumbar puncture with the patient in a seated position. Br J Hosp Med. 2006; 67:M46–M47.

McQuillan, KA. The neurologic system. In: Alspach JA, ed. Core curriculum for critical care nursing. ed 6. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2006:381–524.

Wilson, RK, Williams, MA. Normal pressure hydrocephalus. Clin Geriatr Med. 2006; 22:935–951.

Ziai, WC, Lewin, JJ. Update in the diagnosis and management of central nervous system infections. Neurol Clin. 2008; 26:427–468.