Lumbar Puncture (Perform)

Lumbar Puncture (Perform)

A lumbar puncture is performed for access to the subarachnoid space to obtain a cerebrospinal fluid sample, measure cerebrospinal fluid pressure, drain cerebrospinal fluid, infuse medications or contrast agents, or place a cerebrospinal fluid drainage catheter.1–3,7

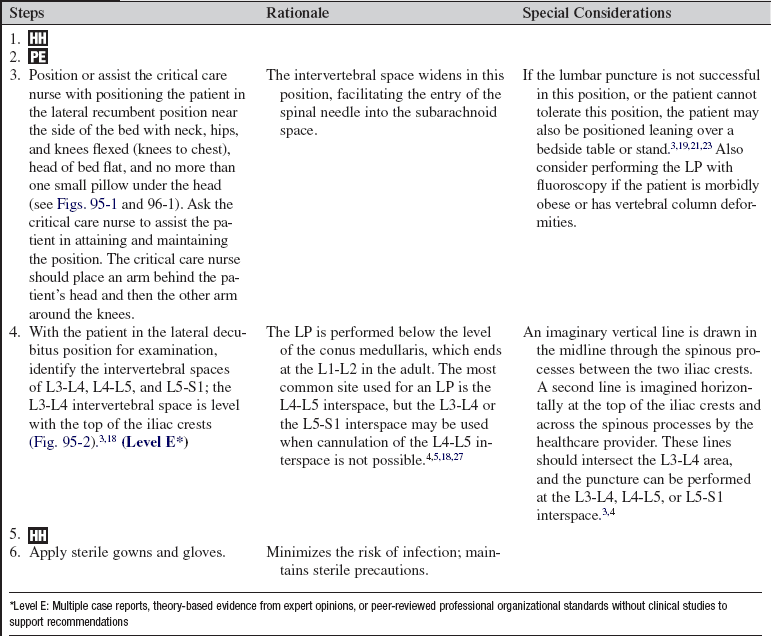

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

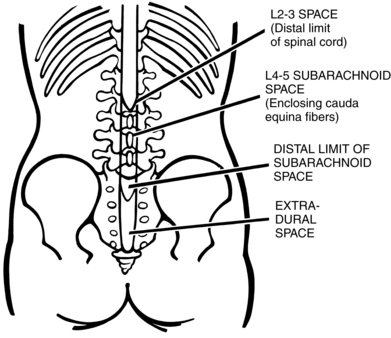

• Knowledge of the anatomy and physiology of the vertebral column, spinal meninges, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) circulation, including the location of the lumbar cistern, is needed.

• Technical and clinical competence in performing lumbar punctures (LPs) is necessary.

• Knowledge of sterile technique is needed.

• The presence of meningeal irritation caused by either infectious meningitis or subarachnoid hemorrhage may promote discomfort when the patient is placed in the flexed, lateral decubitus position for the LP.3–5,17

• Computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) supersedes the routine use of LP for many diagnoses.5,7,18,28

• Indications for LP include the following4,5,18,28:

Suspected central nervous system (CNS) infection

Suspected central nervous system (CNS) infection

Clinical examination results suggestive of subarachnoid hemorrhage accompanied by negative CT scan findings

Clinical examination results suggestive of subarachnoid hemorrhage accompanied by negative CT scan findings

Suspected Guillain-Barré syndrome

Suspected Guillain-Barré syndrome

Intrathecal administration of medications

Intrathecal administration of medications

Imaging procedures that require infusion of contrast agents

Imaging procedures that require infusion of contrast agents

CSF drainage in hydrocephalus, pseudotumor cerebri, or CSF fistula

CSF drainage in hydrocephalus, pseudotumor cerebri, or CSF fistula

• Contraindications for LP include the following3,18,28,29:

Increased intracranial pressure with mass effect

Increased intracranial pressure with mass effect

Superficial skin infection localized to the site of entry

Superficial skin infection localized to the site of entry

Bleeding diathesis (relative contraindication)

Bleeding diathesis (relative contraindication)

Platelet count less than 50,000/mm3

Platelet count less than 50,000/mm3

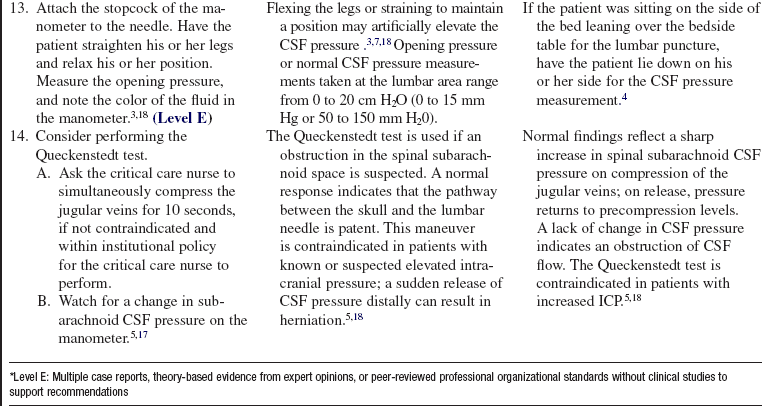

• Normal CSF values include the following18,20,23,28:

Opening pressure, 0 to 15 mm Hg

Opening pressure, 0 to 15 mm Hg

White blood cell count, less than 5/mm

White blood cell count, less than 5/mm

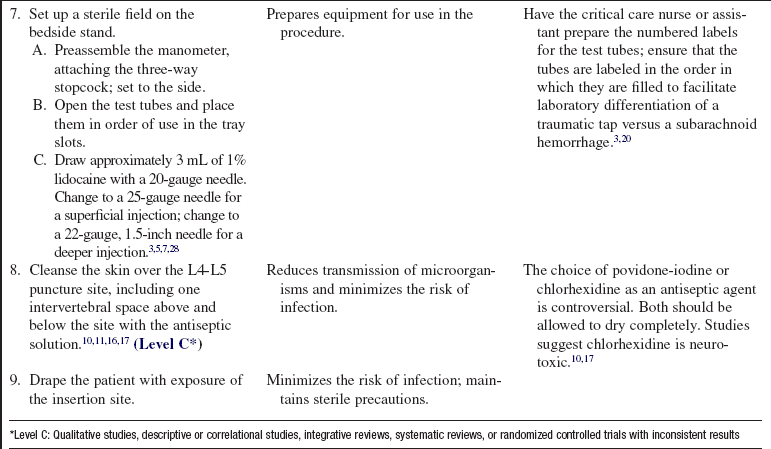

EQUIPMENT

• Sterile gloves, caps, masks with eye shields or goggles, and sterile gowns

• Manometer with three-way stopcock

• Lidocaine, 1% to 2% (without epinephrine)

• 20-, 22-, and 25-gauge needles

• 18-, 20-, or 22-gauge spinal needles

• Four numbered capped test tubes

• Adhesive strip or sterile dressing supplies

• Glucometer/phlebotomy equipment for serum or whole blood glucose

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the purpose of the LP procedure to the patient and family.  Rationale: Explanation may decrease patient and family anxiety.

Rationale: Explanation may decrease patient and family anxiety.

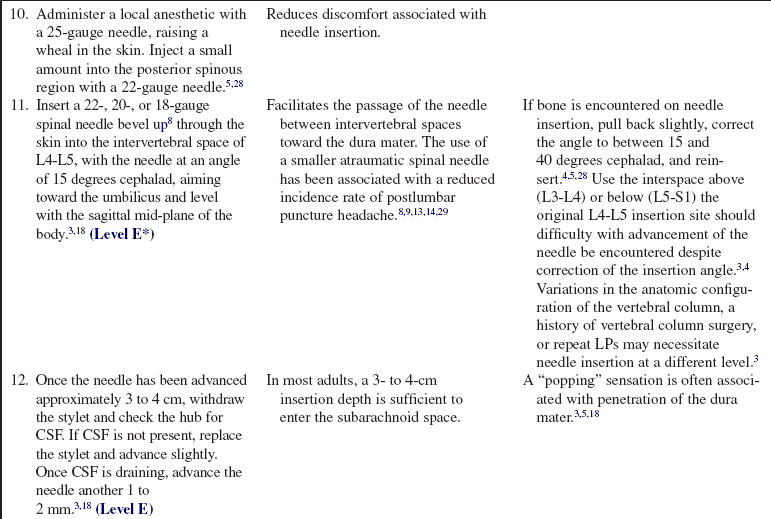

• Explain the need for the patient to remain still and quiet in a lateral decubitus position with the neck, knees, and hips flexed (knees to chest); the axis of the hips vertical; the back close to the edge of the bed; the head of the bed flat; and no more than one pillow under the head (Figs. 95-1 and 96-1). If the lumbar puncture is not successful in this position, or the patient cannot tolerate this position, explain that the patient may also be positioned leaning over a bedside table or stand.5,19,21,23  Rationale: Patient cooperation during the examination is elicited; the intervertebral space widens in these positions, facilitating entry of the spinal needle into the subarachnoid space.2,3,5,6

Rationale: Patient cooperation during the examination is elicited; the intervertebral space widens in these positions, facilitating entry of the spinal needle into the subarachnoid space.2,3,5,6

• Explain that the procedure may produce some discomfort and that local anesthesia is injected to minimize pain. Also, explain that the patient may receive some mild analgesic and anxiolytic agents as prescribed and needed.  Rationale: The patient and family are prepared for what to expect.

Rationale: The patient and family are prepared for what to expect.

• Explain that the patient may find it helpful to lie flat for 1 to 4 hours after the LP.  Rationale: A flat position may promote dural closure; the position was previously thought to reduce the possibility of postprocedural headache, but studies suggest it is not helpful in the prevention of a headache after the procedure.1,5,12

Rationale: A flat position may promote dural closure; the position was previously thought to reduce the possibility of postprocedural headache, but studies suggest it is not helpful in the prevention of a headache after the procedure.1,5,12

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Note any pertinent patient history.  Rationale: An LP is performed to assist with the diagnosis and management of a number of neurologic disease processes (see previous indications for LP).

Rationale: An LP is performed to assist with the diagnosis and management of a number of neurologic disease processes (see previous indications for LP).

• Obtain a baseline neurologic assessment, including assessment for increased intracranial pressure (ICP), before performing the LP.  Rationale: Increased ICP during the LP may place the patient at risk for a downward shift in intracranial contents (brain herniation) when the pressure is suddenly released from the lumbar subarachnoid space.3,18,23,28

Rationale: Increased ICP during the LP may place the patient at risk for a downward shift in intracranial contents (brain herniation) when the pressure is suddenly released from the lumbar subarachnoid space.3,18,23,28

• Assess for coagulopathies, active treatment with heparin or warfarin, local skin infections in close proximity to the site, or pertinent medication allergies.  Rationale: This assessment identifies potential risks for bleeding, infection, and allergic reactions.2–5

Rationale: This assessment identifies potential risks for bleeding, infection, and allergic reactions.2–5

• Assess the patient’s ability to cooperate with the procedure.  Rationale: Sudden, uncontrolled movement may result in needle displacement with associated injury or need for reinsertion.

Rationale: Sudden, uncontrolled movement may result in needle displacement with associated injury or need for reinsertion.

• Identify through history and clinical examination vertebral column deformities or tissue scarring that may interfere with the ability to successfully carry out the procedure.  Rationale: Scoliosis, lumbar surgery with fusion, and repeated LP procedures may interfere with successful cannulation of the subarachnoid space.3,21

Rationale: Scoliosis, lumbar surgery with fusion, and repeated LP procedures may interfere with successful cannulation of the subarachnoid space.3,21

• Assess for signs and symptoms of meningeal irritation, which include the following:

Patient Preparation

• Verify correct patient using two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Ensure that the patient and family understand preprocedural teaching. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

• Obtain informed consent.  Rationale: Informed consent protects the rights of the patient and makes competent decision-making possible for the patient; however, in emergency circumstances, time may not allow for the consent form to be signed.

Rationale: Informed consent protects the rights of the patient and makes competent decision-making possible for the patient; however, in emergency circumstances, time may not allow for the consent form to be signed.

• Perform a pre-procedure verification and time out, if non-emergent.  Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

• Obtain the patient’s history of allergic reactions.  Rationale: History can rule out an allergy to lidocaine, the antiseptic solution, and the analgesia or sedation.

Rationale: History can rule out an allergy to lidocaine, the antiseptic solution, and the analgesia or sedation.

• Prescribe an analgesic medication and/or an anxiolytic medication.  Rationale: These medications may be needed to promote comfort and to decrease anxiety so that positioning can be achieved during the procedure.

Rationale: These medications may be needed to promote comfort and to decrease anxiety so that positioning can be achieved during the procedure.

References

1. Ahmed, SV, Jayawarna, C, Jude, E, Post-lumbar puncture headache. diagnosis and management. Postgrad Med J 2006; 82:713–716.

![]() 2. Armon, C, Evans, RW, Addendum to assessment. prevention of post-lumbar puncture headachesreport of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2005; 65:510–512.

2. Armon, C, Evans, RW, Addendum to assessment. prevention of post-lumbar puncture headachesreport of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2005; 65:510–512.

![]() 3. Boon, JM, Abrahams, PH, Meiring, JH, et al, Lumbar puncture. anatomical review of a clinical skill. Clin Anat 2004; 17:544–553.

3. Boon, JM, Abrahams, PH, Meiring, JH, et al, Lumbar puncture. anatomical review of a clinical skill. Clin Anat 2004; 17:544–553.

4. Ellenby, MS, Tegtmeyer, K, Lai, S, et al. Lumbar puncture. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355:e12.

![]() 5. Euerle, B. Spinal puncture and cerebrospinal fluid examination. In: Roberts JR, Hedges JR, Chanmugam AS, eds. Clinical procedures in emergency medicine. ed 4. St Louis: Elsevier; 2003:1197–1222.

5. Euerle, B. Spinal puncture and cerebrospinal fluid examination. In: Roberts JR, Hedges JR, Chanmugam AS, eds. Clinical procedures in emergency medicine. ed 4. St Louis: Elsevier; 2003:1197–1222.

![]() 6. Evans, RW, Armon, C, Frohman, EM, et al, Assessment. prevention of post-lumbar puncture headachesreport of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2000; 55:909–914.

6. Evans, RW, Armon, C, Frohman, EM, et al, Assessment. prevention of post-lumbar puncture headachesreport of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2000; 55:909–914.

7. Farley, A, McLafferty, FA. Lumbar puncture. Nurs Stand. 2008; 22:46–48.

8. Frank, RL, Lumbar puncture and post-dural puncture headaches. implications for the emergency physician. J Emerg Med 2008; 35:149–157.

9. Gaiser, R. Postdural puncture headache. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2006; 19:249–253.

10. Hebl, JR. The importance and implications of aseptic techniques during regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2006; 31:311–323.

![]() 11. Kinirons, B, Mimoz, O, Lafendi, L, et al. Chlorhexidine versus povidone iodine in preventing colonization of continuous epidural catheters in children. Anesthesiology. 2001; 94:239–244.

11. Kinirons, B, Mimoz, O, Lafendi, L, et al. Chlorhexidine versus povidone iodine in preventing colonization of continuous epidural catheters in children. Anesthesiology. 2001; 94:239–244.

![]() 12. Levine, DN, Rapalino, O. The pathophysiology of lumbar puncture headache. J Neurol Sci. 2001; 192:1–8.

12. Levine, DN, Rapalino, O. The pathophysiology of lumbar puncture headache. J Neurol Sci. 2001; 192:1–8.

13. Lowery, S, Oliver, A. Incidence of postdural puncture headache and backache following diagnostic/therapeutic lumbar puncture using a 22G cutting spinal needle, and after introduction of a 25G pencil point spinal needle. Paediatr Anaesth. 2008; 18:230–234.

![]() 14. Luostarinen, L, Heinonen, T, Luostarinen, M, et al, Diagnostic lumbar puncture. comparative study between 22-gauge pencil point and sharp bevel needle. J Headache Pain 2005; 6:400–404.

14. Luostarinen, L, Heinonen, T, Luostarinen, M, et al, Diagnostic lumbar puncture. comparative study between 22-gauge pencil point and sharp bevel needle. J Headache Pain 2005; 6:400–404.

![]() 15. Manthous, CA, DeGirolamo, A, Haddad, C, et al, Informed consent for medical procedures. local and national practices. Chest 2003; 124:1978–1984.

15. Manthous, CA, DeGirolamo, A, Haddad, C, et al, Informed consent for medical procedures. local and national practices. Chest 2003; 124:1978–1984.

16. Milstone, AM, Passaretti, CL, Perl, TM, Chlorhexidine. expanding the armamentarium for infection control and prevention. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 46:274–281.

17. Reynolds, F. Neurological infections after neuraxial anesthesia. Anesthesiol Clin. 2008; 26:23–52.

![]() 18. Roos, KL. Lumbar puncture. Semin Neurol. 2003; 23:105–114.

18. Roos, KL. Lumbar puncture. Semin Neurol. 2003; 23:105–114.

19. Ropper, AH, Samuel, MA, Special techniques for neurological diagnosisRopper AH, Samuels MA, eds.. Adams and Victor’s principles of neurology. ed 9. McGraw-Hill, New York, 2009.. www.accessmedicine.com.offcampus.lib.washington.edu/content.aspx?aID=3630099 [Text available at].

![]() 20. Seehusen, DA, Reeves, MM, Fomin, DA. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis. Am Fam Physician. 2003; 68:1103–1108.

20. Seehusen, DA, Reeves, MM, Fomin, DA. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis. Am Fam Physician. 2003; 68:1103–1108.

21. Shah, KH, McGillicuddy, D, Spear, J, et al. Predicting difficult and traumatic lumbar punctures. Am J Emerg Med. 2007; 25:608–611.

22. Stiffler, KA, Jwayyed, S, Wilber, ST, et al. The use of ultrasound to identify pertinent landmarks for lumbar puncture. Am J Emerg Med. 2007; 25:331–334.

23. Straus, SE, Thorpe, KE, Holroyd-Leduc J. How do I perform a lumbar puncture and analyze the results to diagnose bacterial meningitis. JAMA. 2006; 296:2012–2022.

![]() 24. Sudlow, CL, Warlow, CC. Epidural blood patching for preventing and treating post-dural puncture headache. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002; 2:CD001791.

24. Sudlow, CL, Warlow, CC. Epidural blood patching for preventing and treating post-dural puncture headache. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002; 2:CD001791.

![]() 25. Sudlow, CL, Warlow, CC. Posture and fluids for preventing post-dural puncture headache. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002; 2:CD001790.

25. Sudlow, CL, Warlow, CC. Posture and fluids for preventing post-dural puncture headache. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002; 2:CD001790.

![]() 26. Turnbull, DK, Shepherd, DB, Post-dural puncture headache. pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment. Br J Anaesth 2003; 91:718–729.

26. Turnbull, DK, Shepherd, DB, Post-dural puncture headache. pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment. Br J Anaesth 2003; 91:718–729.

27. van Kooten, F, Oedit, R, Bakker, SL, et al, Epidural blood patch in post dural puncture headache. a randomised, observer-blind, controlled clinical trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008; 79:553–558.

28. Weaver, JP. Cerebrospinal fluid aspiration. In: Irwin RS, Rippe JM, eds. Irwin and Rippe’s intensive care medicine. ed 6. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008:151–158.

29. Williams, J, Lye, DCB, Umapathi, T, Diagnostic lumbar puncture. minimizing complications. Intern Med J 2008; 38:587–591.

Allen, SH. How to perform lumbar puncture with the patient in a seated position. Br J Hosp Med. 2006; 67:M46–M47.

McQuillan, KA. The neurologic system. In: Alspach JA, ed. Core curriculum for critical care nursing. ed 6. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2006:381–524.

Wilson, RK, Williams, MA. Normal pressure hydrocephalus. Clin Geriatr Med. 2006; 22:935–951.

Ziai, WC, Lewin, JJ. Update in the diagnosis and management of central nervous system infections. Neurol Clin. 2008; 26:427–468.

Rationale: A baseline assessment of neurologic function is established before the introduction of the needle into the subarachnoid space.

Rationale: A baseline assessment of neurologic function is established before the introduction of the needle into the subarachnoid space.