CHAPTER 92 Psychiatry and the Media

HOW THE MASS MEDIA AFFECT PUBLIC UNDERSTANDING OF MENTAL ILLNESS

Surveys in the United States and elsewhere have found that many people have little understanding of what mental illness looks like, what symptoms characterize different illnesses, and what is meant by labels, such as “schizophrenia” and “mania.”1 Despite some progress in recent years, stigmatizing myths about causality persist. For example, a surprisingly large percentage of the general public believes that schizophrenia and depression are caused by “the way a person was raised” or are due to “one’s own bad character.”2 They also tend to underrate the contribution of biological factors.1 Many people harbor a distorted view of the nature and value of psychiatric treatment. While surveys show generally positive views of psychotherapy, misconceptions about medication (e.g., exaggerated concerns about side effects and a belief that drugs merely cover up symptoms) are rampant.3

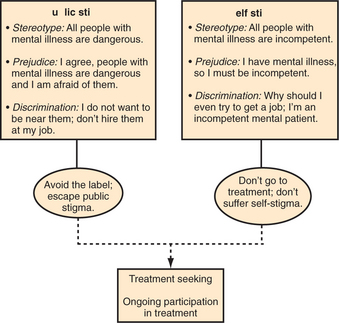

The stigma associated with mental illness is a major reason that many sufferers never seek treatment, do not follow treatment recommendations, or drop out of treatment prematurely (Figure 92-1).4 Children with mental health problems (and their parents) face disdain, blame, and discrimination, in stark contrast to attitudes toward children with “physical” illnesses.5 Research has shown that inaccurate perceptions by parents and teachers regarding children’s mental health problems, and beliefs about treatment (including concerns about stigma that arises from treatment), create major barriers to receiving needed services.6 Given that over three-quarters of children with mental health needs do not receive treatment,7 the removal of barriers to care is a critical priority.

A number of studies point to mass media content as a major source of stigmatization and misinformation. Among people who have little firsthand experience with mental illness, beliefs about what mentally ill people are like and how they should be treated may be shaped primarily by what is read, seen, or heard in the mass media. Reviews of press coverage in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and New Zealand have found that mental illness is frequently linked with violence.8 In one United States study on the reporting of mental illness by major newspapers, the focus of the stories was crimes or violence perpetrated by a mentally ill person 26% of the time, and it was by far the most common theme.9 This increases the desire to avoid persons with mental illnesses.10

Another study of United States newspapers found that the word “schizophrenic” is commonly used as a metaphor in a way that perpetuates perceptions of that illness as a “split personality” (Table 92-1).11 Moreover, hostile media reports can increase self-stigma, as well as discrimination, as perceived by people who struggle with mental illness.12

Table 92-1 Types of References to Cancer and Schizophrenia in United States Newspapers

| Frequency (%)* | ||

|---|---|---|

| Type | Cancer (N = 864) | Schizophrenia (N = 876) |

| Metaphor | 1.3 | 28.1 |

| Obituary | 24.5 | 0 |

| Human interest | 8.6 | 23.1 |

| Medical news | 14.1 | 13.7 |

| Prevention education | 4.4 | 2.4 |

| Incidental reference | 37.7 | 32.3 |

| Medically inappropriate reference | 0 | 1 |

| Charity | 9.4 | 0 |

* X2 = 579.12, df = 7, p < .001

From Duckworth K, Halpern JH, Schutt RK, Gillespie C: Use of schizophrenia as a metaphor in U.S. newspapers. Psychiatric Services 54:1402-1404, 2003.

Entertainment media can also reinforce harmful images and beliefs. For example, a review of Disney animated films found a surprisingly high number of stigmatizing comments, including “crazy” thoughts, ideas, behaviors, or clothing, with the implication that these traits were irrational and inferior.13 Children’s cartoons often portray “twisted” or “nuts” characters as evil or funny.14 Even video games feature negative stereotypes.15 Mental illness is a common theme in movies (including horror films) that are popular with adolescents. These not only present persons with mental illnesses as scary and dangerous, but also distort the public’s perceptions of mental health professionals and their expectations about the nature and outcome of therapy (Table 92-2).16,17 Media portrayals of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) have been particularly distorted. ECT is routinely portrayed in films as brutal and punishing, and even as a method of murder, with no therapeutic benefit.18

Table 92-2 Schneider’s Typology of Movie Psychiatrists and Psychologists

| “Dr. Dippy” | “Dr. Evil” | “Dr. Wonderful” |

|---|---|---|

From Schneider I: The theory and practice of movie psychiatry, Am J Psychiatry 144:996-1002, 1987.

HOW MASS MEDIA INTERVENTIONS CAN AFFECT STIGMA

People who are more familiar with mental illness (e.g., due to personal experience; illness of family, friends, co-workers, or neighbors; or exposure through volunteer or professional work) are less likely to want to distance themselves from people with mental illness, including those with major depression.19 This also seems to be true after “virtual” exposure to models through educational videos.20 Drawing on this research, and the research noted previously on the roots of stigma, the goal of many recent educational interventions has been to make the public feel comfortable with mentally ill individuals, and to refute stigmatizing ideas about the causes and treatment of mental illness.

The planning of anti-stigma initiatives has become more sophisticated, with efforts to target key attitudes or behaviors of specific populations.21 One approach is to reach out through the mass media (using television, radio, films, and the Internet). The World Psychiatric Association’s (WPA’s) Programme to Reduce Stigma and Discrimination Because of Schizophrenia, begun in 1996, has programs in over 20 countries.22 The WPA recommends a “social marketing” approach to planning outreach campaigns that includes targeting specific subgroups (e.g., criminal justice personnel), conducting needs assessments to inform the design of media messages, and pretesting media materials before embarking on expensive campaigns.

The Royal College of Psychiatrists in Great Britain has sponsored several campaigns, including Defeat Depression from 1992 to 199623 and Changing Minds from 1998 to 2003.24,25 Surveys found encouraging, but small, shifts in attitudes (e.g., regarding perceptions of dangerousness, and whether a mentally ill person is to blame for his or her condition). Perhaps the most-studied anti-stigma campaign is New Zealand’s Like Minds, Like Mine.26,27 This research-based campaign includes strategically placed television, radio, and cinema advertisements (some featuring nationally known and respected people who had experience with mental illness), public relations activities to support the advertising messages (including media interviews and placed articles), and more targeted locally based education and grassroots activities. National tracking surveys found that awareness of campaign messages was high and that significant changes in attitudes and behavior were evident, as were reports of reduced stigma and discrimination.

It is critical to note that simply teaching facts about mental illness is not sufficient to dispel stigma. Despite their greater knowledge, psychiatrists and other mental health professionals often hold more stigmatizing attitudes toward the mentally ill than do members of the general public.28 It is also important to monitor anti-stigma efforts for the creation of unintended harmful effects. For example, recent research suggests that labeling mental illnesses as biologically based “brain diseases” could increase perceptions of dangerousness and the desire for social distance from mentally ill persons.29 Similarly, comparison of mental illness to chronic illnesses (such as diabetes and allergies), if overemphasized, could inappropriately discount the effects of mental illness, and create new misperceptions.30

EFFECTS OF MASS MEDIA ON SUICIDE

A large body of multinational research demonstrates unequivocally that exposure to media reports of suicide can increase suicide attempts and deaths. Research reviews have found that stories of both fictional and real-life suicides can lead to imitation, but the effect of news stories tends to be greater.31,32 Several factors seem to increase the likelihood of imitation; these include stories of celebrities (entertainers or politicians) who commit suicide; extensive, prominent news coverage of the suicide; coverage that glamorizes or sensationalizes the suicide; and detailed descriptions of the suicide method. Imitation is decreased if the negative consequences of suicide (such as disfigurement of the body, a cult-related suicide, or suffering of and condemnation by the survivors) are portrayed. Adolescents and young adults may be particularly prone to imitate suicides that are portrayed in the media, especially when the stories are of victims in their age-group.33

A 1-year study of over 4,600 newspaper, radio, and television reports related to suicide in Australian media found a larger effect from television stories than either radio or newspapers (contrary to some earlier studies that found newspaper stories more influential).34 A greater effect was also seen when multiple reports of suicide occurred close together, and when stories addressed completed suicides as opposed to suicide attempts or ideation.

Evidence suggests that changing the content and tone of news coverage of suicide can affect suicide rates. In Vienna, the opening of a new subway system led to an increase in subway suicides that was exacerbated by dramatic media reports. Creation of a suicide prevention media campaign, and guidelines for news reporters, led to a dramatic decrease in attempted and completed subway suicides.35 New guidelines for media reporting on suicide suggest ways that psychiatrists can help educate the public.36 When interviewed by reporters, it is important to stress the connection between mental illness (especially depression) and suicide, and to provide information on resources to prevent suicides and to help survivors of suicide. One should avoid weighted language, such as “committed,” “failed,” or “successful” when describing suicide; these words imply criminality or judgment of outcomes, which makes it difficult to put suicide into the content of mental health.

EFFECTS OF MEDIA CONTENT ON CHILDREN’S BEHAVIOR

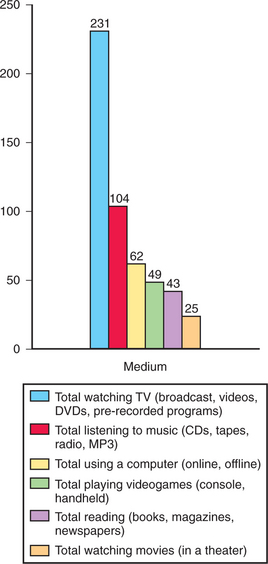

For modern American children, interacting with mass media is essentially a full-time job. A 2005 national survey of children (ages 8 to 18) about their media use found that children devote an average of nearly 6.5 hours per day to contact with media (including print material) (Figure 92-2).37 About one-quarter of children’s media time involved “multitasking,” or using multiple media at the same time. Despite the proliferation of new media, watching live or prerecorded content on television still claims the largest piece of media time: nearly 4 hours per day. Two-thirds of children had a television in their bedroom at home; these children spent more time watching television and less time reading than did their peers. Encouragingly, time spent with media did not appear to take time away from parents, friends, sports, or peers; in fact, heavy media users were more likely to interact with others. However, another recent study found that the amount of time children under age 12 spent watching television, alone or with parents (measured via media diaries completed by caregivers), was negatively correlated to time spent with parents on other activities.38

The effect of media content (especially violent content) on children’s behavior is a long-standing concern of psychiatrists, parents, and policy makers. Unfortunately, studies of media’s effects are difficult to conduct. Children cannot be randomly assigned to use or to avoid media. Longitudinal studies are hampered by problems with measures and definitions (e.g., total television viewing time used as a proxy for exposure to violence), and by the fact that media content and technology are constantly evolving. Correlational studies cannot demonstrate causality, or the direction of any relationship that may exist between media content and behavior. Finally, experimental studies rarely measure effects of media exposure on actual physical violence; typical outcome measures (such as changes in attitudes or feelings measured directly after exposure) may be of limited use in the prediction of real-world violence.39

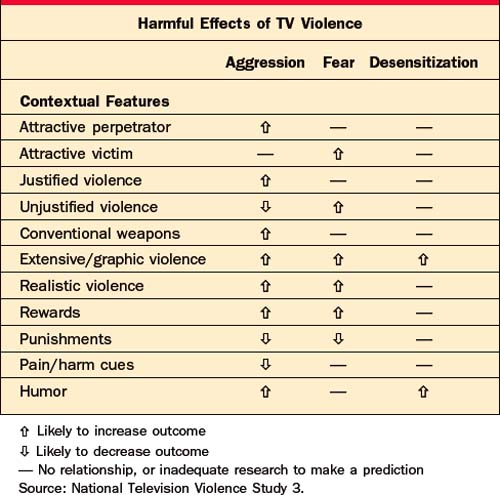

Despite these limitations, a large body of research strongly suggests that television and other electronic media can teach violent behavior and attitudes, desensitize viewers to violence, and promote fears of becoming a victim of violence. However, the effects of violent content depend on how violence is portrayed, as well as on a child’s characteristics (such as developmental stage, aggressivity, and previous life experiences), and the social and physical context of media use. All of these affect the meaning and interpretation of the violence, and ultimately the lessons learned by viewers.40

The largest study of violent content to date, the National Television Violence Study,41 involved content analyses of 10,000 hours of television programming (dramas, comedies, movies, music videos, “reality” programs, and children’s shows) (Table 92-3). Content defined as “violent” included credible threats of violence, use of force intended to harm “an animate being or group of beings,” and the harmful consequences of unseen violent acts. Under that definition, two-thirds of programs were found to contain violence, with an average of six violent acts per hour.

While violent content has received the most attention, mass media also shape children’s understanding of social rela-tionships and their expectations about behavior and appearance. Television, movies, magazines, and electronic games frequently present children with unrealistic and unhealthy body images. A large prospective study of children ages 9 to 14 found that making efforts to look like same-sex media images predicted the development of weight concerns and constant dieting in girls and boys.42

Other risky behaviors are also affected by mass media. For example, a longitudinal study of children ages 10 to 15 found a dose-response relationship between hours of television watching and the initiation of smoking.43 Those who watched 5 or more hours per day were six times more likely to start smoking than those who watched less than 2 hours, even after controlling for some other risk factors.

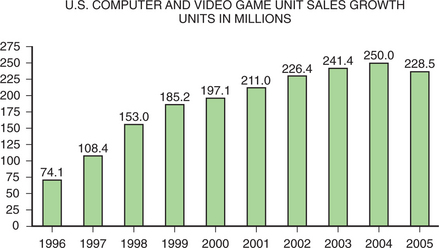

The availability and use of interactive games have increased dramatically over the past decade. On an average day, half (52%) of American children ages 8 to 18 play games on a console or handheld player, and one-third (35%) play games on a computer.37 Game content is increasingly realistic and best-selling games are frequently violent, which raises concerns among clinicians, parents, and policy makers that exposure to such games could be a risk factor, or a trigger, for real-life aggression (Figure 92-3).

Figure 92-3 Video game unit sales by year.

(Redrawn from Entertainment Software Association: Essential facts about the computer and video game industry: 2006 sales, demographic and usage data.)

Dozens of studies have been published about the effects of electronic interactive games on children and adolescents. Most research has centered on potential negative consequences (such as increased aggression, low school grades, and desensitization to violence).44,45 Some reviews of research on violent video games conclude that more study is needed,46 especially regarding subgroups of children,47 or that game effects are small or mixed48; others conclude that the evidence supports a large and consistent effect of violent games on aggressive thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, and that ongoing exposure of large numbers of youth to violent games could have major societal consequences.49

Some studies have looked at the effects of interactive games (both specially designed and commercially available games) on health and well-being. Depending on the con-tent, interactive games may promote the development of cognitive skills (such as spatial representation, interpreting diagrams [iconic skills], and visual attention).50 Video games have shown promise as a therapeutic tool for pain management and physiotherapy, for the conveyance of social skills to children with disabilities (such as autism),51 and for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in war veterans.52

More research is needed on the differential effects of media on children with mental illnesses (such as depression and attention-deficit disorder). Some children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are adept at video games and using computers, which can provide a highly valued source of self-esteem. Judicious use of interactive games may enhance both social relationships and classroom learning for boys with ADHD.53 Anecdotal reports also suggest a need to study uses of video games in psychotherapy.

MEDIA LITERACY: ADVISING PARENTS ON MEDIA USE

Most children age 8 and below cannot reliably tell fantasy from reality, and cannot comprehend complex motives and intentions. They focus more on how something looks than what is said about it.54 Older children can begin to grasp more subtle aspects of program content (such as plots, themes, and historical or geographical setting), and how these combine with technical elements to affect how the program makes them feel. They can also start to question the motivations behind characters’ behaviors (from sexuality to substance use) and aspects of their appearance (such as clothing or weight), and identify harmful stereotypes (such as the portrayal of “crazy people”). This analytical approach to understanding the purposes and effects of media is referred to as “media literacy.”

These sorts of questions can form the underpinnings of discussions with older children as parents watch television programs or commercials with them55:

The proliferation and ubiquity of media technologies make it difficult for parents to monitor the content available to their children. A variety of tools and resources are available to assist parents in this task. A summary of rating systems for television, films, music, and video games is available at www.parentalguide.org. This site is sponsored by entertainment industry groups; it also links to each of their sites, where frequently asked questions about the rating systems are answered. The Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC’s) Web site also provides information, and allows parents to file complaints.56

New technologies make it easier to control children’s use of television, computers, and video game consoles, even when parents are absent. As of January 1, 2000, the Federal Communications Commission has required all television sets larger than 13 inches to include technology that allows parents to block access to inappropriate programs. The “V-Chip” allows parents to use a “parental lock code” as a password to activate or change V-Chip settings. Programs can be blocked by age category or content label. For example, a parent may block all programs rated TV-14, or only those that contain violence (TV-14-V). The V-Chip can also block movies via Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) ratings (such as PG-13 and R), including unedited films on premium cable channels. Unfortunately, the V-Chip can be difficult to locate and complicated to program, especially given parents’ often-limited understanding of the ratings system. A 2001 survey found that only 7% of parents had used a V-Chip.57

Providers of cable television are legally required to offer “lockboxes” for sale or lease on customer request. Some cable set-top boxes or keypads come equipped with parental controls. More advanced digital equipment may allow multiple options, including blocking by date, time, channel, program title, and TV or film rating (Table 92-4).58

From www.parentalguide.org.

Home computers are a concern in terms of access to inappropriate content (such as pornography) and release of private, identifying information. The 1998 Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act requires that Web site operators post their privacy policy and obtain parental consent before collecting, using, or disclosing personal information about a child. Parents may also review personal information collected on their children, and choose to revoke consent and delete it. Information on policies, as well as advice for parents, teachers, and children on safe Internet use, is available on the FTC Web site.59

GetNetWise.org,60 a Web site supported by a coalition of industry and advocacy groups, has an online safety guide that provides advice tailored to children’s ages and likely activities (including chat, e-mail, instant messaging, and newsgroups). For example, as preteens begin to master abstract thinking and are able to explore more content on their own, it is important to talk about the credibility of Web content and how to determine the quality or biases of what they find. The site also reviews the technologies available to families to restrict access to Internet content, including tools that block outgoing content or limit time spent online (total time or times of day); tools that monitor children’s online activity (such as storing addresses of Web sites visited); and tools that filter or block content by Web site address (URL) or that review Web pages or key words. Filtering software is controversial because it can overblock and prevent access to innocuous sites, or underblock and allow offensive material to slip through. A 2000 survey found that roughly one-third of parents with home Internet access had used a filtering device.61 No technology can replace parental monitoring, or discussions with children on how to handle the inevitable exposure to inappropriate or upsetting material.

HOW PSYCHIATRISTS CAN USE MASS MEDIA TO EDUCATE AND COUNTERACT STIGMA

The most straightforward way to educate the public about mental illness is to reach out through popular channels of information. In a 2001 survey,62 51% of respondents said that television (especially TV news programs) was their most important source of news and information about health issues. While clinicians and researchers may recognize the power of mass media as public health and education tools for mental health promotion, primary prevention, and stigma reduction, few psychiatrists receive any formal training in how to use those tools. In addition, many are concerned that attempts to work with the media will be viewed by colleagues as self-promotion rather than public education.

There are three general types of “triggers” for contact with mass media:

For example, recent concerns and publicity over the use of antidepressant medications by children provided child psychiatrists with opportunities to reach out to the press not only on that specific topic, but on the nature of childhood mood disorders, the purpose and limits of these types of studies, and the predicaments of parents who are seeking help for children who have mental illnesses.

If the story is based on newly published research, it is important to provide information that helps reporters put those findings into perspective. For example, a mention in one small study that a quarter of patients with schizophrenia carried weapons during psychotic episodes led to histrionic headlines about dangerous mental patients.63 One should be explicit about what the data mean and what they do not tell us, and what the practical implications might be. Whenever possible, one should attempt to put the data into a real-world context. If the goal is to increase the recognition of depression, it is more compelling to state that every high school classroom has at least one student with undiagnosed depression—and to give examples of what untreated depression might mean for that child’s future—than to recite statistics. Thinking in terms of examples and visual images also helps to put information into lay language (Table 92-5).

Table 92-5 Key Points in Working With Journalists on Mental Health Stories

While more published studies are needed, evidence shows that reaching out to reporters with accurate background information and ideas for positive stories can improve the amount and tone of mental health coverage.64 If psychiatrists can overcome their discomfort and develop realistic expectations and clear goals, working with the media can often be a positive experience. For clinicians, several results are evident: it provides opportunities to counter misinformation and stereotypes; it removes barriers to appropriately seeking diagnosis and treatment; it improves therapeutic relationships, compliance with treatment, and treatment outcomes; and it increases social and political support for families who struggle with mental illness. It is also important to network with colleagues locally and internationally to increase knowledge of innovative and effective ways to use mass media for the benefit of the public’s mental health.

1 Jorm AF. Mental health literacy: public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:396-401.

2 Link BG, Phelan JC, Bresnahan M, et al. Public conceptions of mental illness: labels, causes, dangerousness, and social distance. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1328-1333.

3 Priest RG, Vize C, Roberts A, et al. Lay people’s attitudes to treatment of depression: results of opinion poll for Defeat Depression campaign just before its launch. Br Med J. 1996;313:858-859.

4 Corrigan P. How stigma interferes with mental health care. Am Psychol. 2004;59:614-625.

5 Weissman MM. Stigma (a piece of my mind). JAMA. 2001;285:261-262.

6 Owens PL, Hoagwood K, Horwitz SM, et al. Barriers to children’s mental health services. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:731-738.

7 Coyle JT, Pine DS, Charney SD, et al. Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance consensus statement on the unmet needs in diagnosis and treatment of mood disorders in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:1494-1503.

8 Wahl OF. News media portrayal of mental illness: implications for public policy. Am Behav Sci. 2003;46:1594-1600.

9 Wahl OF, Wood A, Richards R. Newspaper coverage of mental illness: is it changing? Psychiatr Rehab Skills. 2002;6(1):9-31.

10 Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H. The effect of violent attacks by schizophrenic persons on the attitude of the public towards persons with mental illnesses. Soc Sci Med. 1996;43(12):1721-1728.

11 Duckworth K, Halpern JH, Schutt RK, Gillespie C. Use of schizophrenia as a metaphor in US newspapers. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:1402-1404.

12 Clarke J. Mad, bad and dangerous: the media and mental illness. Mental Health Practice. 2004;7(10):16-19.

13 Lawson A, Fouts G. Mental illness in Disney animated films. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49:310-314.

14 Wilson C, Nairn R, Coverdale J, Panapa A. How mental illness is portrayed in children’s television: a prospective study. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:440-443.

15 Wahl OF. Depictions of mental illnesses in children’s media. J Mental Health. 2003;12(3):249-258.

16 Butler JR, Hyler SE. Hollywood portrayals of child and adolescent mental health treatment: implications for clinical practice. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2005;14(3):509-522.

17 Hyler SE. Stigma continues in Hollywood. Psychiatr Times. 2003;20:33-34.

18 Walter G, McDonald A. About to have ECT? Fine, but don’t watch it in the movies. Psychiatr Times. 2004;21:65-68.

19 Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H, Corrigan PW. Familiarity with mental illness and social distance from people with schizophrenia and major depression. Schizophrenia Res. 2004;69:175-182.

20 Reinke RR, Corrigan PW, Leonhard C, et al. Examining two aspects of contact on the stigma of mental illness. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2004;23(3):377-389.

21 Corrigan PW. Target-specific stigma change: a strategy for impacting mental illness. Psychiatr Rehab J. 2004;28(2):113-121.

22 Warner R. Local projects of the World Psychiatric Association programme to reduce stigma and discrimination. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56:570-575.

23 Paykel ES, Hart D, Priest RG. Changes in public attitudes to depression during the Defeat Depression campaign. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;173(12):519-522.

24 Byrne P. Stigma of mental illness and ways of diminishing it. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2000;6:65-72.

25 Crisp AH, Gelder MG, Rix S, et al. Stigmatisation of people with mental illness. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:4-7.

26 Vaughan G, Hansen C. “Like Minds, Like Mine”: a New Zealand project to counter the stigma and discrimination associated with mental illness. Australas Psychiatry. 2004;12(2):113-117.

27 New Zealand Ministry of Health: Like Minds, Like Mine national plan 2003-2005, Wellington, NZ, September 2003.

28 Nordt C, Rossler W, Lauber C. Attitudes of mental health professionals towards people with schizophrenia and major depression. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32:709-714.

29 Dietrich S, Matschinger H, Angermeyer MC. The relationship between biogenetic causal explanations and social distance toward people with mental disorders: results from a population survey in Germany. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2006;52(2):166-174.

30 Why having a mental illness is not like having diabetes. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:846-847.

31 Gould M. Suicide and the media. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;932:200-224.

32 Stack S. Suicide in the media: a quantitative review of studies based on nonfictional stories. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2005;35:121-133.

33 Gould M, Jamieson P, Romer D. Media contagion and suicide among the young. Am Behav Sci. 2003;46:1269-1284.

34 Pirkis JE, Burgess PM, Francis C, et al. The relationship of media reporting of suicide and actual suicide in Australia. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:2874-2886.

35 Etzersdorfer E, Sonneck G. Preventing suicide by influencing mass-media reporting: the Viennese experience 1980-1996. Arch Suicide Res. 1998;4:67-74.

36 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, et al: Reporting on suicide: recommendations for the media. Available at www.afsp.org/education/recommendations/5/1.htm.

37 Roberts DF, Foehr UG, Rideout V. Generation M: media in the lives of 8-18 year-olds. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation, 2005.

38 Vandewater EA, Bickham DS, Lee JH. Time well spent? Relating television use to children’s free-time activities. Pediatrics. 2006;117:181-191.

39 Cantor J. Media violence. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27S:30-34.

40 Huesmann LR, Taylor LD. The role of media violence in violent behavior. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;17:393-415.

41 Smith SL, Wilson BJ, Kunkel D, et al. Violence in television programming overall: University of California Santa Barbara study. In: Federman J, editor. National television violence study 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1998.

42 Field AE, Camargo CAJr, Taylor CB, et al. Peer, parent, and media influences on the development of weight concerns and frequent dieting among preadolescent and adolescent girls and boys. Pediatrics. 2001;107:54-60.

43 Gidwani PP, Sobol A, DeJong W, et al. Television viewing and initiation of smoking among youth. Pediatrics. 2002;110:505-508.

44 Gentile DA, Lynch PJ, Linder JR, Walsh DA. The effects of violent video game habits on adolescent hostility, aggressive behaviors and school performance. J Adolesc. 2004;27:5-22.

45 Funk JB. Children’s exposure to violent video games and desensitization to violence. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2005;14:387-404.

46 Bensley L, van Eenwyk J. Video games and real-life aggression: review of the literature. J Adolesc Health. 2001;29:244-257.

47 Olson CK. Media violence research and youth violence data: why do they conflict? Acad Psychiatry. 2004;28:144-150.

48 Sherry JL. The effects of violent video games on aggression: a meta-analysis. Hum Commun Res. 2001;27(3):409-431.

49 Anderson CA. An update on the effects of playing violent video games. J Adolesc. 2004;27:113-122.

50 Subrahmanyam K, Greenfield P, Kraut R, Gross E. The impact of computer use on children’s and adolescents’ development. Appl Dev Psychol. 2001;22:7-30.

51 Griffiths M. Video games and health. Br Med J. 2005;331:122-123.

52 Rizzo A, Pair J, McNerney PJ, et al. Development of a VR therapy application for Iraq war veterans with PTSD. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2005;111:407-413.

53 Houghton S, Milner N, West J, et al. Motor control and sequencing of boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) during computer game play. Br J Educ Technol. 2004;35(1):21-34.

54 Hoffner C, Cantor J. Developmental differences in responses to a television character’s appearance and behavior. Dev Psychol. 1985;21:1065-1074.

55 Kaiser Family Foundation: Key facts: media literacy, pub no 3383, Fall 2003.

56 FTC Web Site on Entertainment Ratings: About the ratings. Available at www.ftc.gov/bcp/conline/edcams/ratings/ratings.htm.

57 Parents and the V-Chip 2001: A Kaiser Family Foundation survey, pub no 3158, July 2001.

58 Federal Communications Commission: Consumer facts: how to prevent viewing objectionable television programs. Available at www.fcc.gov/cgb/information_directory.html.

59 Federal Trade Commission: How to protect kids’ privacy online, February 2000. Available at www.ftc.gov/bcp/conline/edcams/kidzprivacy/.

60 GetNetWise (Internet Education Foundation): Available at www.getnetwise.org.

61 Annenberg Public Policy Center. Media in the home. Philadelphia: Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania, 2000.

62 , Kaiser/Harvard School of Public Health Program on the Public and Health Policy: Sources of health news and information Kaiser/Harvard Health News Index;6, 5, September/October 2001: Available at www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/3189-index.cfm.

63 Ferriman A. The stigma of schizophrenia. Br Med J. 2000;320(7233):522.

64 Stuart H. Stigma and the daily news: evaluation of a newspaper intervention. Can J Psychiatry. 2003;48:651-656.