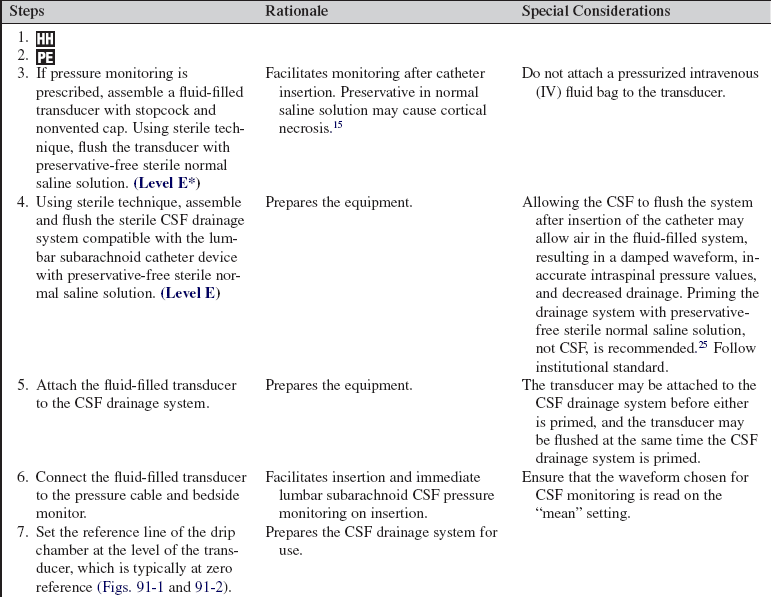

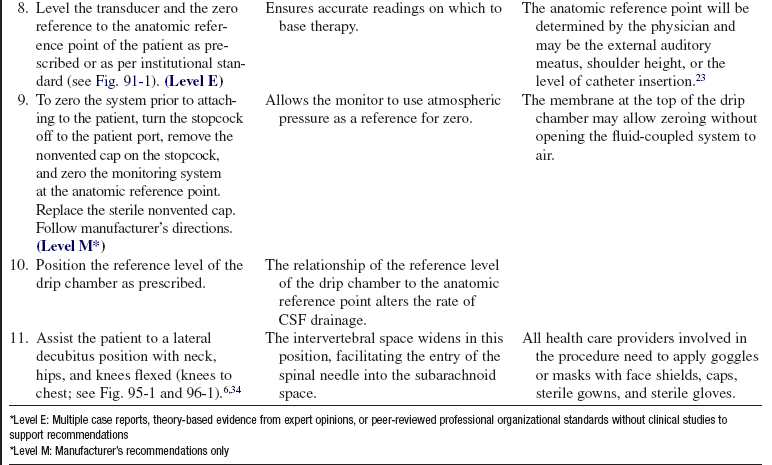

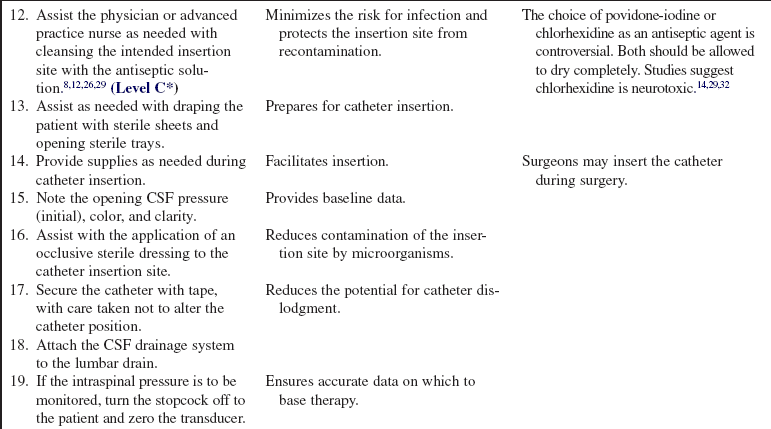

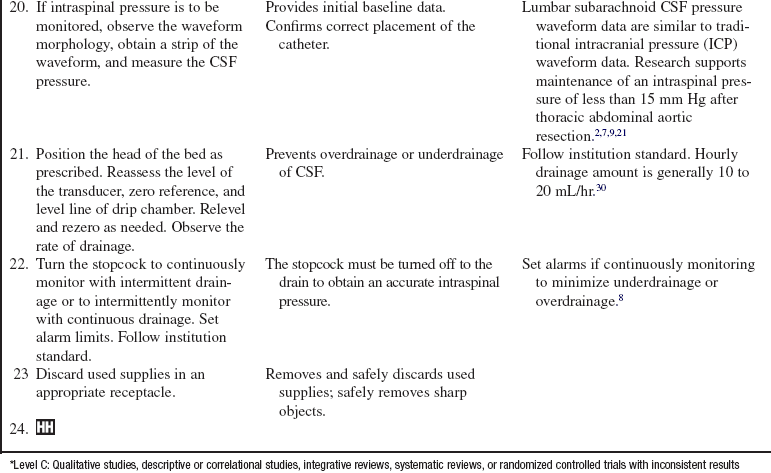

Lumbar Subarachnoid Catheter Insertion (Assist) for Cerebrospinal Fluid Drainage and Pressure Monitoring

Patients with a variety of central nervous system conditions and thoracoabdominal aneurysms may benefit from monitoring of intraspinal pressure and maintenance of therapeutic levels of cerebrospinal fluid drainage. Lumbar subarachnoid catheters are used for cerebrospinal fluid pressure monitoring and drainage.23,40

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• Knowledge of the anatomy and physiology of the vertebral column, spinal meninges, spinal cord, nerve roots, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) circulation and intracranial and intraspinal dynamics is needed.

• Knowledge of aseptic technique is necessary.

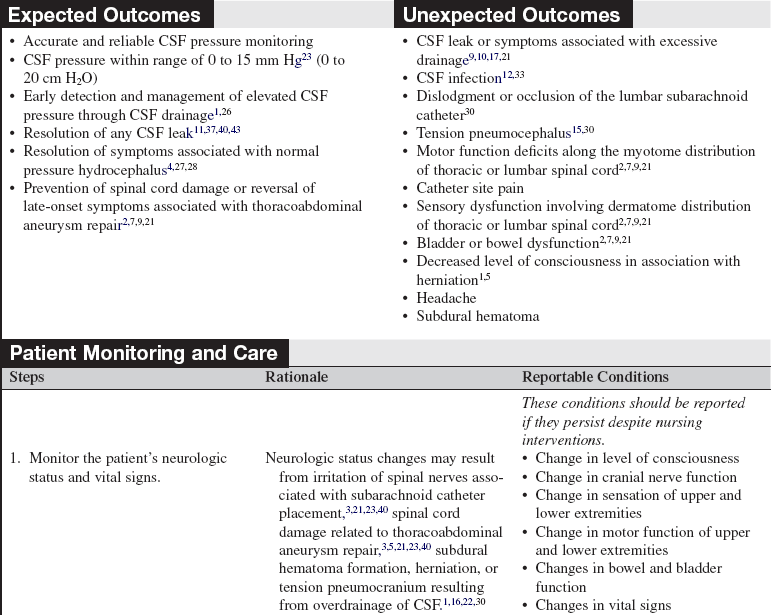

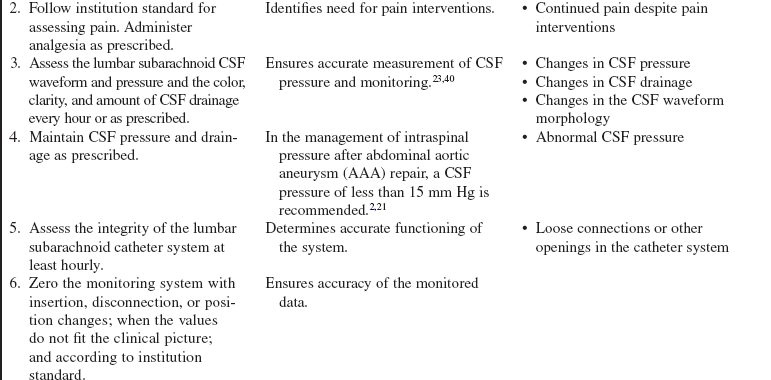

• Normal intraspinal pressure in the adult is 0 to 20 cm H2O (0 to 15 mm Hg or 50 to 150 mm H2O) and usually corresponds with intracranial pressure.24 Intraspinal pressure may be influenced by a number of factors. Further research is needed to ascertain therapeutic levels after various surgical interventions.21

• Lumbar subarachnoid catheters, also referred to as lumbar drains or intrathecal catheters, require lumbar puncture (LP) for insertion.16 Lumbar subarachnoid catheters permit monitoring of CSF pressure. CSF pressure may be monitored intermittently or continuously, and CSF drainage may be performed intermittently or continuously.23,40

• Lumbar subarachnoid catheters may be used in the prevention or management of spontaneous, traumatic, or surgical CSF fistulas to allow any tears in the dura mater to heal.37,41–44 The catheter reduces moisture and pressure at the tear and may be placed before, during, or after surgery.4,8,11,37,41

• Lumbar subarachnoid catheters may be used in the diagnostic workup and management of normal pressure hydrocephalus instead of serial lumbar punctures.12,27,28

• Lumbar subarachnoid catheters may be used in the perioperative management of intraspinal pressure during and after thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysmal repair to provide adequate room in the intraspinal space to accommodate spinal cord edema and to improve impaired spinal cord perfusion related to spinal cord edema.

• Lumbar subarachnoid catheters may be used instead of or with an external ventricular drain to decrease intracranial pressure and remove blood from the subarachnoid space, which may lessen aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage vasospasm.13,16,22,26,36 When ventricular and lumbar drainage are used simultaneously, the ventricular drainage output should exceed the lumbar drainage output to lessen the risk of herniation.12,16,22,38

• Lumbar subarachnoid catheters may be use in the management of communicating hydrocephalus related to intraventricular, intracerebral hemorrhage.18,19

• Complications related to the use of lumbar subarachnoid catheters include infection, headache, nerve root irritation, retained fragments of broken catheters, paraplegia, and neurologic deterioration related to overdrainage, including subdural hematomas, pneumocephalus, and herniation.1,30,31,33

• Lumbar subarachnoid catheters have been used, with extreme caution, in the management of patients with meningitis.26

• Lumbar subarachnoid catheter drainage is contraindicated with midline mass effect. A computed tomographic (CT) scan before lumbar subarachnoid catheter insertion to confirm discernible basal cisterns and absence of a mass lesion may lessen the risk of herniation.1,16,21,22

• A variety of products are available for lumbar subarachnoid catheter drainage systems, making it essential to follow the manufacturer’s guidelines for management of the patient23 to include the type of pressure measurement unit used for patient monitoring (e.g. monitoring pressures in units mm Hg, cm H2O).

EQUIPMENT

• Caps, masks with face shields, sterile gowns, and sterile gloves

• Sterile towels, half-sheets, and drapes

• Local anesthetic (lidocaine 1% or 2% without epinephrine)

• 5- or 10-mL Luer-Lok syringe with 18-gauge needle for drawing of lidocaine and 23-gauge needle for administration of lidocaine

• Sutures (2-0 nylon, 3-0 silk)

• Preservative-free sterile normal saline solution (vial, bag, or prefilled syringe)

• External transducer with three-way stopcock

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Assess the patient and family understanding of the lumbar subarachnoid catheter system.  Rationale: Any necessary clarification may limit anxiety for the patient and family.

Rationale: Any necessary clarification may limit anxiety for the patient and family.

• Explain insertion, patient monitoring, and care involving the lumbar subarachnoid catheter.  Rationale: Knowledge of expectations can minimize anxiety and encourage questions regarding goals, duration, and expected outcomes of the lumbar subarachnoid catheter.

Rationale: Knowledge of expectations can minimize anxiety and encourage questions regarding goals, duration, and expected outcomes of the lumbar subarachnoid catheter.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Assess the patient’s neurologic status, including level of consciousness, cranial nerves, sensory and motor function in the upper and lower extremities, vital signs, and bowel and bladder function.  Rationale: Baseline data are provided.

Rationale: Baseline data are provided.

• Assess the patient’s current laboratory profile, including complete blood count (CBC), with platelets, partial thromboplastin time (PTT), prothrombin time (PT), and international normalized ratio (INR).  Rationale: Baseline coagulation study results determine the risk for bleeding during and after lumbar subarachnoid catheter insertion.16,26,36

Rationale: Baseline coagulation study results determine the risk for bleeding during and after lumbar subarachnoid catheter insertion.16,26,36

• Assess the patient’s medication profile.  Rationale: Recent anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents may increase the risk of bleeding during and after lumbar subarachnoid catheter insertion.

Rationale: Recent anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents may increase the risk of bleeding during and after lumbar subarachnoid catheter insertion.

• Assess known allergies.  Rationale: Usual medications used during the procedure may be contraindicated by allergy.

Rationale: Usual medications used during the procedure may be contraindicated by allergy.

Patient Preparation

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Ensure that informed consent is obtained.  Rationale: Informed consent protects the rights of the patient and makes competent decision-making possible for the patient; however, in emergency circumstances, time may not allow for the consent form to be signed.

Rationale: Informed consent protects the rights of the patient and makes competent decision-making possible for the patient; however, in emergency circumstances, time may not allow for the consent form to be signed.

• Administer preprocedural analgesia or sedation as prescribed.  Rationale: The patient must be correctly positioned and immobile during lumbar subarachnoid catheter insertion and monitoring and therefore may need sedation or analgesia to tolerate the procedure.

Rationale: The patient must be correctly positioned and immobile during lumbar subarachnoid catheter insertion and monitoring and therefore may need sedation or analgesia to tolerate the procedure.

• Administer preprocedural antibiotics as prescribed.  Rationale: Prophylactic intravenous antibiotics may reduce the risk of infection.

Rationale: Prophylactic intravenous antibiotics may reduce the risk of infection.

• Perform a pre-procedure verification and time out, if non-emergent.  Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

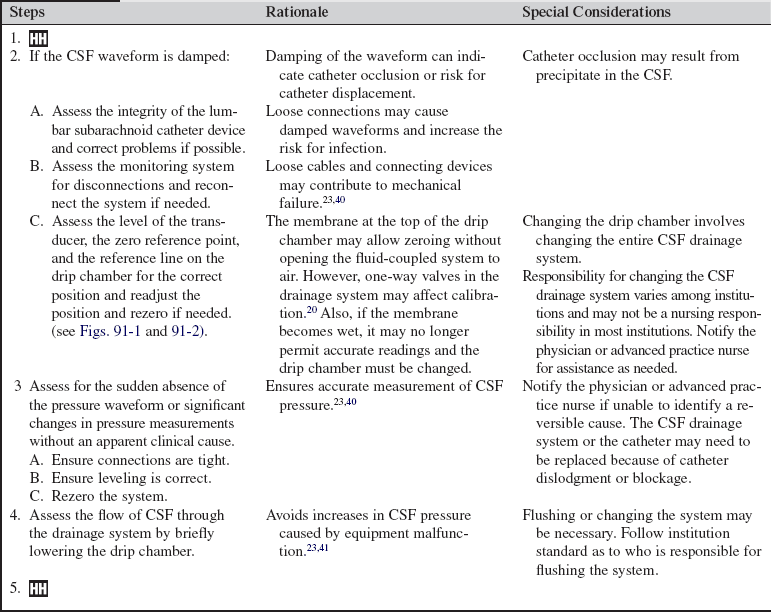

Figure 91-2 Top of the drip chamber with reference line.

References

1. Abadal-Centellas JM, et al. Neurologic outcome of post-traumatic refractory intracranial hypertension treated with external lumbar drainage. J Trauma. 2007; 62:282–286.

2. Bajwa, A, et al, Paraplegia following elective endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. reversal with cerebrospinal fluid drainage. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2007; 35:46–48.

![]() 3. Bhama, JK, Lin, PH, Voloyiannis, T, et al. Delayed neurologic deficit after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2003; 37:690–692.

3. Bhama, JK, Lin, PH, Voloyiannis, T, et al. Delayed neurologic deficit after endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2003; 37:690–692.

4. Bien, AG, et al. Utilization of preoperative cerebrospinal fluid drain in skull base surgery. Skull Base. 2007; 17:133–139.

![]() 5. Bloch, J, Regli, L, Brain stem and cerebellar dysfunction after lumbar spinal fluid drainage. case report. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003; 74:992–994.

5. Bloch, J, Regli, L, Brain stem and cerebellar dysfunction after lumbar spinal fluid drainage. case report. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003; 74:992–994.

![]() 6. Boon, JM, Abrahams, PH, Meiring, JH, et al, Lumbar puncture. anatomical review of a clinical skill. Clin Anat 2004; 177:544–553.

6. Boon, JM, Abrahams, PH, Meiring, JH, et al, Lumbar puncture. anatomical review of a clinical skill. Clin Anat 2004; 177:544–553.

![]() 7. Cina, CS, et al, Cerebrospinal fluid drainage to prevent paraplegia during thoracic and thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm surgery. a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Vasc Surg 2004; 40:36–44.

7. Cina, CS, et al, Cerebrospinal fluid drainage to prevent paraplegia during thoracic and thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm surgery. a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Vasc Surg 2004; 40:36–44.

8. Dalgic, A, et al, An effective and less invasive treatment of post-traumatic cerebrospinal fluid fistula. closed lumbar drainage system. Minim Invas Neurosurg 2008; 51:154–157.

![]() 9. Fleck, TM, et al, Improved outcome in thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair. the role of cerebrospinal fluid drainage. Neurocrit Care 2005; 2:11–16.

9. Fleck, TM, et al, Improved outcome in thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair. the role of cerebrospinal fluid drainage. Neurocrit Care 2005; 2:11–16.

10. Fountas, KN, et al. Review of the literature regarding the relationship of rebleeding and external ventricular drainage in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage of aneurysmal origin. Neurosurg Rev. 2006; 29:14–18.

11. Friedman, RA, et al. Management of cerebrospinal fluid leaks after acoustic tumor removal. Neurosurgery. 2007; 61:35–39. [(Suppl)].

12. Greenberg, BM, Williams, MA. Infectious complications of temporary spinal catheter insertion for diagnosis of adult hydrocephalus and idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurosurgery. 2008; 62:431–435.

13. Hanggi, D, et al, The effect of lumboventricular lavage and simultaneous low-frequency head-motion therapy after severe subarachnoid hemorrhage. results of a single center prospective phase II trial. J Neurosurg 2008; 108:1192–1199.

14. Hebl, JR. The importance and implications of aseptic techniques during regional anesthesia. Regional Anesth Pain Med. 2006; 31:311–323.

![]() 15. Hetherington, NJ, Dooley, MJ. Potential for patient harm from intrathecal administration of preserved solutions. Med J Aust. 2000; 173:141–143.

15. Hetherington, NJ, Dooley, MJ. Potential for patient harm from intrathecal administration of preserved solutions. Med J Aust. 2000; 173:141–143.

16. Hoekema, D, Schmidt, RH, Ross, I, Lumbar drainage for subarachnoid hemorrhage. technical considerations and safety analysis. Neurocrit Care 2007; 7:3–9.

![]() 17. Houle, PJ, et al. Pump-regulated lumbar subarachnoid drainage. Neurosurgery. 2000; 46:929–932.

17. Houle, PJ, et al. Pump-regulated lumbar subarachnoid drainage. Neurosurgery. 2000; 46:929–932.

18. Huttner, HB, Schwab, S, Bardutzky, J. Lumbar drainage for communicating hydrocephalus after ICH with ventricular hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2006; 5:193–196.

19. Huttner, HB, et al, Intracerebral hemorrhage with severe ventricular involvement. lumbar drainage for communicating hydrocephalus. Stroke 2007; 38:183–187.

20. Integra, Accudrain external CSF drainage systems. reference insert-8400,. Integra, Plainsboro NJ, 2008.

![]() 21. Khan, SN, Stansby, GP. Cerebrospinal fluid drainage for thoracic and thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4, 2003. [CD003635].

21. Khan, SN, Stansby, GP. Cerebrospinal fluid drainage for thoracic and thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4, 2003. [CD003635].

![]() 22. Klimo, P, et al. Marked reduction of cerebral vasospasm with lumbar drainage of cerebrospinal fluid after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2004; 100:215–224.

22. Klimo, P, et al. Marked reduction of cerebral vasospasm with lumbar drainage of cerebrospinal fluid after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2004; 100:215–224.

23. Leeper, B, Lovasik, D, Cerebrospinal drainage systems. external ventricular and lumbar drainsLittlejohns LR, Bader MK, eds.. Monitoring technologies in critically ill neuroscience patients. Jones and Bartlett: Boston, 2009:71–101.

24. Lenfeldt, N, Koskinen, OD, Bergenheim, AT, et al. CSF pressure assessed by lumbar puncture agrees with intracranial pressure. Neurology. 2007; 68:155–158.

![]() 25. Littlejohns, LR, Trimble, B, Ask the experts. our policy on external ventricular drainage systems includes the procedure for priming the systemdoes it really have to be primed. Crit Care Nurse 2005; 25:57–59.

25. Littlejohns, LR, Trimble, B, Ask the experts. our policy on external ventricular drainage systems includes the procedure for priming the systemdoes it really have to be primed. Crit Care Nurse 2005; 25:57–59.

26. Manosuthi, W, et al. Temporary external lumbar drainage for reducing elevated intracranial pressure in HIV-infected patients with cryptoccoccal meningitis. Int J STD AIDS. 2008; 19:268–271.

![]() 27. Marmarou, A, et al. The value of supplemental prognostic tests for the preoperative assessment of idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery. 2005; 57(Suppl 2-17):S2–28.

27. Marmarou, A, et al. The value of supplemental prognostic tests for the preoperative assessment of idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery. 2005; 57(Suppl 2-17):S2–28.

![]() 28. McGirt, MJ, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and analysis of long-term outcomes in idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery. 2005; 57:699–705.

28. McGirt, MJ, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and analysis of long-term outcomes in idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery. 2005; 57:699–705.

29. Milstone, AM, Passaretti CL Perl TM, Chlorhexidine . expanding the armamentarium for infection control and prevention. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 46:274–281.

![]() 30. Moza, K, et al. Indications for cerebrospinal fluid drainage and avoidance of complications. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2005; 38:577–582.

30. Moza, K, et al. Indications for cerebrospinal fluid drainage and avoidance of complications. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2005; 38:577–582.

31. Olivar, H, et al, Subarachnoid lumbar drains. a case series of fractured catheters and a near miss. Can J Anaesth 2007; 54:829–834.

32. Reynolds, F. Neurological infections after neuraxial anesthesia. Anesthesiol Clin. 2008; 26:23–52.

33. Roca, B, Pesudo, JV, Gonzalex-Darder JM. Meningitis caused by Enterococcus gallinarum after lumbar drainage of cerebrospinal fluid. Eur J Int Med. 2006; 17:298–299.

![]() 34. Roos, KL. Lumbar puncture. Semin Neurol. 2003; 23:105–114.

34. Roos, KL. Lumbar puncture. Semin Neurol. 2003; 23:105–114.

35. Ropper, AH, Samuels, MA, Special techniques for neurologic diagnosis Text available atRopper AH, Samuels MA, eds.. Adams and Victor’s principles of neurology. ed 9. 2009. www.accessmedicine.com.offcampus.lib.washington.edu/content.aspx?aID=3630099

![]() 36. Ruijs, AC, et al. The risk of rebleeding after external lumbar drainage in patients with untreated ruptured cerebral aneurysms. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2005; 147:1157–1162.

36. Ruijs, AC, et al. The risk of rebleeding after external lumbar drainage in patients with untreated ruptured cerebral aneurysms. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2005; 147:1157–1162.

37. Sade, B, Mohr, G, Frenkiel, S, Management of intra-operative cerebrospinal fluid leak in transnasal transsphenoidal pituitary microsurgery. use of post-operative lumbar drain and sellar reconstruction without fat packing. Acta Neurochi (Wien) 2006; 148:13–19.

![]() 38. Samadani, U, et al. Intracranial hypotension after intraoperative lumbar cerebrospinal fluid drainage. Neurosurgery. 2003; 52:148–152.

38. Samadani, U, et al. Intracranial hypotension after intraoperative lumbar cerebrospinal fluid drainage. Neurosurgery. 2003; 52:148–152.

39. Schade, RP, et al. Lack of value of routine analysis of cerebrospinal fluid for prediction and diagnosis of external drainage-related bacterial meningitis. J Neurosurg. 2006; 104:101–108.

40. Schlosser, RJ, et al, Spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid leaks. a variant of benign intracranial hypertension. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2006; 115:495–500.

41. Thompson, H, Avanecean, D. Care of the patient with the lumbar drain, ed 2, Glenview, IL, American Association of Neuroscience Nurses. www.aann.org/pubs/guidelines.html, 2007. [Text available at].

![]() 42. Van Aken MO, et al, Cerebrospinal fluid leakage during transsphenoidal surgery. postoperative external lumbar drainage reduces the risk for meningitis. Pituitary 2004; 7:89–93.

42. Van Aken MO, et al, Cerebrospinal fluid leakage during transsphenoidal surgery. postoperative external lumbar drainage reduces the risk for meningitis. Pituitary 2004; 7:89–93.

43. Viswanathan, A, et al, Use of lumbar drainage of cerebrospinal fluid for brain relaxation in occipital lobe approaches in children. technical note. Surg Neurol 2009; 71:681–684.

44. Yilmazlar, S, et al, Cerebrospinal fluid leakage complicating skull base fractures. analysis of 81 cases. Neurosurg Rev 2006; 29:64–71.