History

Comments

Current Medications

Current Symptoms

Physical Examination

Comments

Laboratory Data

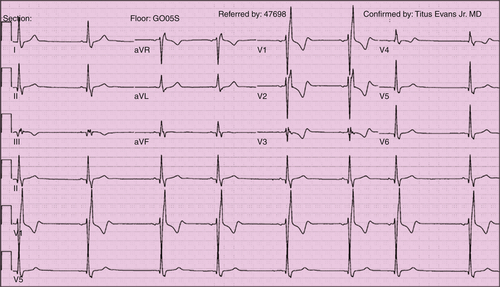

Electrocardiogram

Findings

FIGURE 9-1

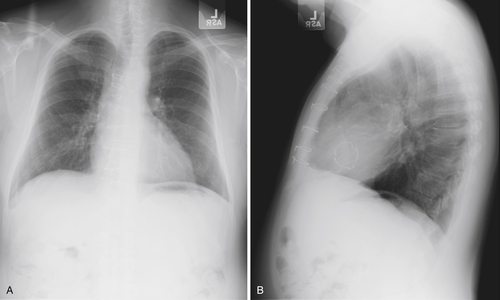

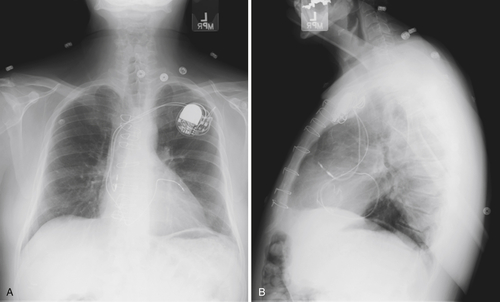

Chest Radiograph

Findings

Exercise Testing

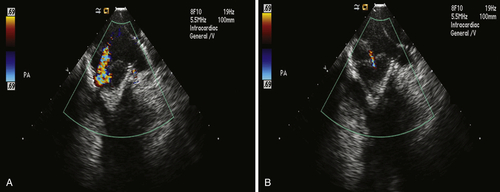

Echocardiogram

Findings

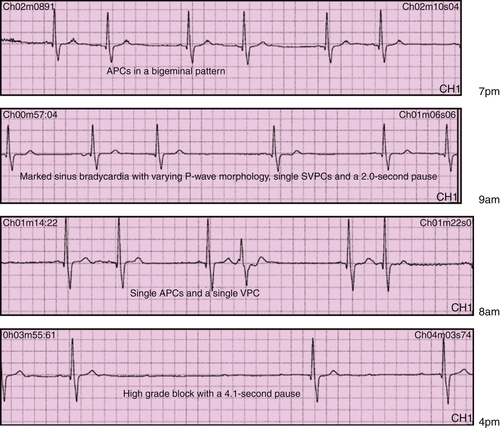

Physiologic Tracings

Findings

Focused Clinical Questions and Discussion Points

Discussion

Question

Discussion

Question

Discussion

Question

Discussion

Final Diagnosis

Plan of Action

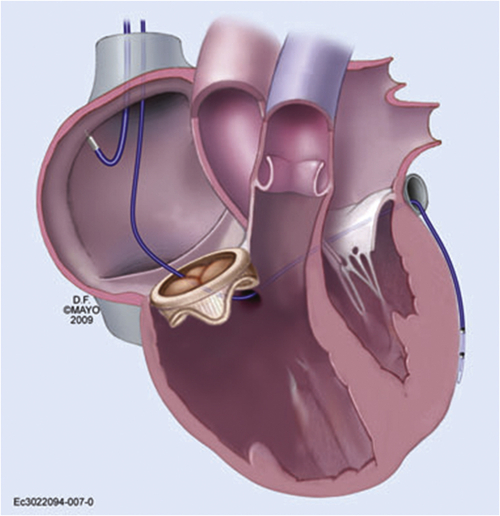

Intervention

FIGURE 9-4

Outcome

FIGURE 9-5

FIGURE 9-6

Selected References

1. Bleeker G.B., Schalij M.J., Nihoyannopoulos P. et al. Left ventricular dyssynchrony predicts right ventricular remodeling after cardiac resynchronization therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:2264–2269.

2. Eleid M.F., Blauwet L.A., Cha Y.-M. et al. Bioprosthetic tricuspid valve regurgitation associated with pacemaker or defibrillator lead implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:813–818.

3. McLeod C.J., Attenhofer Jost C.H., Warnes C.A. et al. Epicardial versus endocardial permanent pacing in congenital heart disease. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2010;28:235–243.