History

Current Medications

Comments

Current Symptoms

Comments

Physical Examination

Laboratory Data

Comments

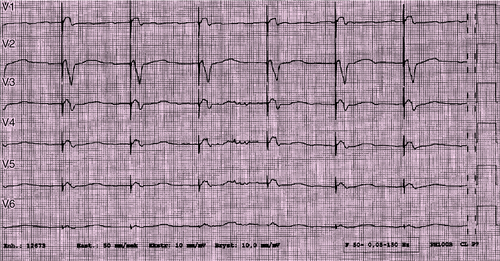

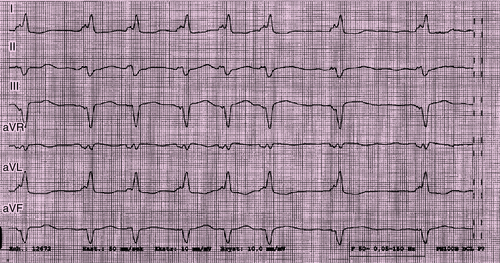

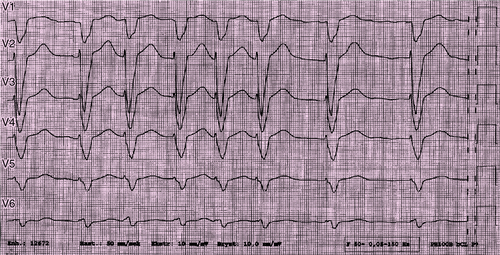

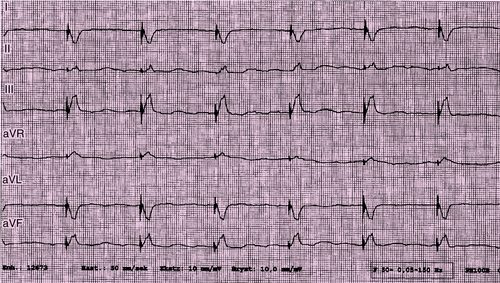

Electrocardiogram

Findings

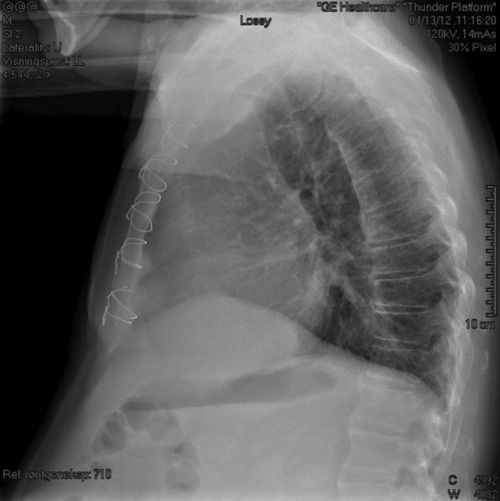

Chest Radiograph

Findings

FIGURE 29-1

FIGURE 29-2

FIGURE 29-3

FIGURE 29-5

FIGURE 29-6

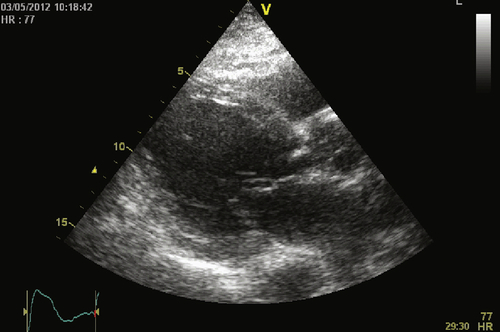

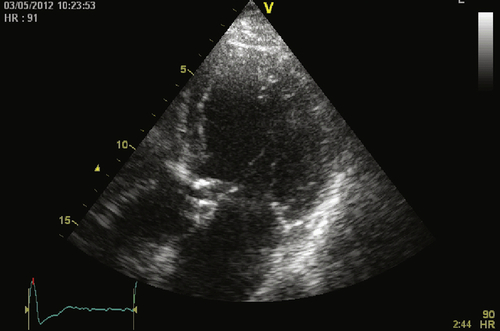

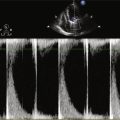

Echocardiogram

Findings

Findings

Focused Clinical Questions and Discussion Points

Question

Discussion

Question

Discussion

Question

Discussion

Question

Discussion

Final Diagnosis

Plan of Action

Intervention

Outcome

Selected References

1. Dickstein K., Bogale N., Priori S. et al. The european cardiac resynchronization therapy survey. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2450-–2460.

2. Ganesan A.N., Brooks A.G., Roberts-Thomson K.C. et al. Role of AV nodal ablation in cardiac resynchronization in patients with coexistent atrial fibrillation and heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:719–726.

3. Gasparini M., Auricchio A., Metra M. et al. Long-term survival in patients undergoing cardiac resynchronization therapy: the importance of performing atrio-ventricular junction ablation in patients with permanent atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:1644–1652.

4. Gasparini M., Auricchio A., Regoli F. et al. Four-year efficacy of cardiac resynchronization therapy on exercise tolerance and disease progression. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:734–743.

5. Hayes D.L., Boehmer J.P., Day J.D. et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy and relationship of percent biventricular pacing to symptoms and survival. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:1469–1475.

6. Healey J.S., Hohnloser S.H., Exner D.V. et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with permanent atrial fibrillation: results from the Resynchronization for Ambulatory Heart Failure Trial (RAFT). Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5:566–570.

7. Jensen-Urstad M. Should all patients undergoing atrioventricular junction ablation receive cardiac resynchronization therapy? Europace. 2012;14:1383–1384.

8. Kamath G.S., Cotiga D., Koneru J.N. et al. The utility of 12-lead Holter monitoring in patients with permanent atrial fibrillation for the identification of nonresponders after cadiac resynchronization therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1050–1055.

9. McMurray J.J.V., Adamopoulos S., Anker S.D. et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1787–1847.

10. Stavrakis S., Garabelli P., Reynold D.W. Cardiac resynchronization therapy after atrioventricular junction ablation for symptomatic atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis. Europace. 2012;14:1490–1497.