CHAPTER 9. Abortion ethics and the nursing profession

L earning objectives

▪ Examine critically the definitions of abortion used respectively by pro-abortionists and anti-abortionists.

▪ Identify two key issues upon which the abortion issue turns.

▪ Discuss critically the following three positions on abortion:

1. the conservative position

2. the moderate position

3. the liberal position.

▪ Outline at least six contemporary developments informing the ‘new ethics of abortion’ and its possible implications for the abortion debate generally.

▪ Discuss briefly the common arguments advanced both for and against the view that the fetus is not a person.

▪ Discuss at least three instances in which the rights of a fetus (once granted) might come into conflict with the rights of others.

▪ Discuss critically whether the nursing profession should formulate a public position on the abortion issue.

I ntroduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that, each year, approximately 42 million women faced with an unplanned pregnancy will decide to have an abortion (WHO 2007b). Of these, around 20 million women (mostly in developing countries) will be forced, primarily because of restrictive abortion laws, to resort to unsafe abortions — defined as ‘a procedure for terminating an unintended pregnancy either by individuals without the necessary skills or an environment that does not conform to minimum medical standards or both’ (Grimes et al 2006: 1908). Of those women undergoing unsafe abortion, WHO estimates that one in four will likely experience severe complications, including death, and that in the developing world a woman dies every 8 minutes from the complications of unsafe abortions. WHO further estimates that the ill-health arising from unsafe abortion accounts for at least 13% of global maternal mortality (around 68000 women annually) and around 20% of the ‘overall burden of maternal death and long-term sexual and reproductive health’ (WHO 2007b; see also Grimes et al 2006; Singh 2006).

Unsafe abortion has been identified as one of the most easily preventable causes of maternal ill-health and death, yet it continues to threaten the health and lives of women globally. This has led some commentators to declare that ‘ending the silent pandemic of unsafe abortion is an urgent public-health and human-rights imperative’ (Grimes et al 2006). In response to the issues and challenges raised by this situation, the WHO (2003, 2007b) has deemed ‘preventing unsafe abortion’ a strategic priority underpinned by the following two goals:

▪ in circumstances where abortion is not against the law, to ensure that abortion is safe and accessible

▪ in all cases, women should have access to quality services for the management of complications arising from abortion.

Even though the WHO has identified safe abortion as a strategic global priority, abortion as such remains a deeply contentious and divisive issue. Of all the bioethical issues that command public attention today, perhaps none is more controversial than the ethics of abortion. Although abortion has been legal in many countries for several decades now, its moral permissibility continues to be the subject of heated public debate. Significantly, the polarity of values and views underpinning the abortion controversy has threatened to divide nations, has seen abortion clinics firebombed and abortion workers fatally shot by pro-life fanatics, and has even brought down governments (Hadley 1996).

Despite the legislative and moral reforms of the past five decades, women’s so-called ‘reproductive rights’ (including the right to safe abortion) are still constantly being challenged (Cave 2004; Meredith 2005). And despite being ‘sensationally and bewilderingly public’, abortion for many women remains a deeply private, personal and even taboo subject (Hadley 1996: xi). Even in so-called ‘liberal’ democratic countries where individualism and a person’s right to make important life choices (including the right to choose death) is highly respected and even enshrined in law, women are often forced to justify their need of an abortion in a way ‘that many find to be degrading and intrusive’ (Greenwood 2001: ii3). And while there is much rhetoric about women having ‘reproductive autonomy’, doctors and the courts that legitimate their authority, ultimately have the power to decide if, when, how and under what circumstances a woman’s reproductive rights will be exercised (Cave 2004; Greenwood 2001; Hadley 1996; Meredith 2005; see also Gillon 2001; Hewson 2001; Wyatt 2001; Pojman & Beckwith 1994).

In recent years, a ‘new ethics of abortion’ has emerged (Greenwood 2001; Gillon 2001; Wyatt 2001). This ‘new ethic’ is rekindling the fires of old controversies surrounding the moral status of the fetus and posing new challenges to modern moral thought about the permissibility and impermissibility of abortion. Processes informing the ‘new ethics of abortion’ include the following five developments, which Wyatt (2001: ii15–ii18) believes ‘have irreversibly altered the ethical debate about abortion in Western societies’:

1. advances in fetal physiology (these have made it possible to confirm that fetuses have ‘a range of sophisticated abilities with well developed sensory perception in all systems: vision, hearing, touch, taste and smell’; it is now known that even very young fetuses have the capacity to imitate facial expressions, breathe and initiate hand–face contact, startle, sucking and swallowing movements)

2. development of fetal medicine as a speciality (making it possible to discern major abnormalities and to ‘provide seamless medical care for the fetus through the intrauterine period and on into the critical first hours and days of birth’; it is now possible to provide such intrauterine treatment as blood transfusions and curative surgery for congenital defects)

3. development of neonatal intensive care and improved survival of extremely preterm infants (with developments in specialised neonatal intensive care techniques, it is now commonplace for preterm babies of just 23–24 weeks of gestation to survive; the survival of preterm babies of just 22 weeks weighing less than 500 g at birth has also been described)

4. changed perspective on the rights of the disabled (many in the disabled rights movement regard the abortion of fetuses with genetic disorders or other disabling conditions to be discriminatory and as being prejudicial against disabled people)

5. changes in professional counselling (research has shown that the way information is given to parents can significantly influence the choices they make; this, in turn, has given rise to a new imperative for so-called ‘non-directive counselling’).

Other developments prompting ‘new’ debate on the abortion issue is the growth of ‘wrongful life’ or ‘wrongful birth’ lawsuits and, more recently, ‘wrongful abortion’ suits. ‘Wrongful birth’ suits are based broadly on the argument that a given infant ‘should never have been allowed to be born’ (Forrester & Griffiths 2005: 192). For example, a child may have been born with severe and irremediable disabilities in circumstances where, if appropriate medical advice and care had been provided, a decision not to continue the pregnancy would have been made (see, e.g. Forrester & Griffiths 2005: 192–4). In such cases, an infant’s mother generally seeks compensation on grounds that she was deprived of the opportunity to have an abortion within a relevant time because of a health worker’s (e.g. a doctor’s or a counsellor’s) negligence (e.g. failed abortion; misdiagnosis of fetal abnormality after screening; misdiagnosis of maternal illness which could have resulted in fetal abnormality) (Shapira 1998; Petersen 1997).

‘Wrongful abortion’ lawsuits, in contrast, concern situations in which a pregnant woman is ‘induced to undergo an abortion by a negligent conduct (usually a medical misrepresentation)’ (Perry & Adar 2005: 507). For example, a woman might decide to have an abortion based on advice received from her attending medical practitioner that her fetus is at risk of being born with severe birth defects because of a drug she has taken. After the abortion is performed, however, she learns that the medical advice she was given about the risks to her fetus ‘was a negligent misrepresentation, and that the termination of the pregnancy was unnecessary’ (Perry & Adar 2005: 507). In such cases, the woman might sue for compensation for the catastrophic loss she has suffered.

The above issues help to demonstrate the complexities of the abortion issue and the tensions involved. Just what the outcome of the ‘new ethics of abortion’ will be, remains an open question. What is clear, however, is that there is ‘no Olympian perspective from which these issues can be viewed in benign and omniscient neutrality’ (Wyatt 2001: ii19).

The abortion issue is not ‘new’ to the nursing profession. As shown by the examples given in the previous editions of this book, nurses historically have had to face a range of personal, political and professional difficulties (including being discriminated against and losing their jobs) on account of moral disagreements in the workplace concerning the abortion issue. Research has also revealed that nurses (including those who choose to work in abortion services) frequently face a range of other complexities, tensions and dilemmas inherent in abortion work on account of trying to ‘accommodate the requirements of society, the women patients, and their own beliefs’ (Huntington 2002: 276), and having to work within hospital environments that lack appropriate structures for and even legitimate negative institutional attitudes towards therapeutic abortion work (Chiapetta-Swanson 2005). The difficulties experienced by nurses have been compounded by the fact that the ‘physical experience, psychological distress and decisions’ inherent in abortion work have not been comprehensively considered from a nursing perspective (Huntington 2002: 276; see also Chiapetta-Swanson 2005).

Despite the hardships that nurses have had to carry in the past and continue to carry in the present, the nursing profession globally has been relatively silent on the ‘abortion question’. Just why this silence has prevailed is a matter for speculation. Nevertheless, one thing is clear: this position cannot be sustained, at least not credibly. Given the WHO’s stance on safe abortion as a global health issue, and growing calls in some countries (e.g. the UK) for nurses to undertake first trimester abortions and to ‘take over from doctors’ who are otherwise opposed to undertaking abortion work (Boseley 2006; StaffNurse.com 2007), it is becoming increasingly evident that the nursing profession cannot avoid public debate on the matter and must prepare itself to take a stand. This, in turn, demands that attention be given to addressing a number of critical questions including, but not limited to, the following:

1. What is abortion?

2. Is abortion morally right or wrong?

3. If abortion is morally wrong, can members of the nursing profession be decently expected to assist with abortion work and/or care for the women who have had them?

4. If abortion is not morally wrong, can nurses justifiably refuse to assist with abortion work and/or care for the women who have had them?

5. If participating in abortion work, what are the obligations (if any) of nurses toward fathers of a pregnancy who are opposed to their fetus being aborted?

6. In the event of no substantive agreement being reached on whether abortion is morally right or wrong, what, if any, public position should the nursing profession take on the issue?

7. How should the nursing profession decide these things?

It is to addressing these and related questions that this chapter will now turn.

W hat is abortion?

Before advancing this discussion any further, it is important to first clarify the meaning of the term ‘abortion’. In keeping with lay dictionary definitions, abortion (from Latin abortāre, from aboriri to miscarry, from ab — wrongly, badly) may be defined simply as the ‘premature termination of a pregnancy by either spontaneous or induced expulsion of a nonviable fetus from a uterus’ ( Collins Australian Dictionary 2005), and usually entails the death of the fetus (Warren 2007). Not all participating in the abortion debate subscribe to such a ‘simple’ definition, however. Instead, most lean towards definitions of abortion that while appearing to be value-neutral (objective) are, in essence, ethically loaded and hence at risk of misleading moral debate on the issue. For instance, those who are opposed to abortion typically define abortion in such terms as ‘artificially causing the miscarriage of an unborn child’, or ‘killing an innocent human being’ (Fisher & Buckingham 1985). Definitions of abortion using these or similar terms are not just defining the ‘act’ of abortion, however. They also seem to be conveying the conclusion that abortion is morally wrong (at the very least, the terms used — ‘unborn child’/‘innocent human being’ — seem to appeal to our moral intuition that killing another person who is a non-aggressor is a morally terrible action). In contrast, those who support abortion tend to define abortion in such terms as ‘terminating pregnancy’ or ‘ridding the products of unwanted/unviable conception’. Definitions of abortion using these and similar terms seem to imply that abortion is not only not morally wrong but may even be morally neutral (the term used ‘ridding the products of unwanted conception’ seems to invite the ‘reasonable’ question of: What is so morally terrible about getting rid of something that is ‘unwanted’ and/or incapable of normal growth and development?).

It is unlikely that a consensus will be reached among contesting parties on a working definition of abortion and that variant ethically loaded definitions will continue to be used. Either way, it is important to remember that the issues at hand need to be decided by careful deliberation, not by definitions; they also need to be examined in a manner that will question rather than reinforce the status quo.

I s abortion morally permissible?

The permissibility of abortion has an interesting history. Anthropological studies suggest that abortion has been widely practised across cultures and throughout human history, and probably dates back even to prehistoric times (Thomas 1986: 77). Abortion techniques have been described in early Chinese, Egyptian and Greek texts, and continue to be widely practised in non-industrialised societies and other Third World countries. Muslim traditions permit abortion, so long as it is procured while ‘the embryo is unformed in human shape’ (Thomas 1986: 79). Japan did not introduce anti-abortion laws until the Meiji Restoration (1869–1912).

Contrary to what many Christian fundamentalists believe, opposition to abortion is not justified by appealing to either the Bible (it simply ‘does not discuss it’ [Badham 1987]), to church traditions or to Christian reasoning. The early religious fathers, including St Augustine, St Jerome and St Thomas Aquinas, did not believe that the embryo was a human being from the moment of conception, and ‘all insisted that early abortion could not be classed as homicide’ (Badham 1987: 11). They also drew a firm distinction between early and late abortions. As far as the ‘personhood’ of the fetus is concerned, this too ‘has virtually no significant support’ in the Christian tradition until the teachings of Pope Pius IX (1846–1878). And in the Hebrew version of Exodus 21, accidental abortion is seen as an offence (and one punishable by death) ‘only if the woman dies’ (Thomas 1986: 78).

From where then have contemporary views opposing the moral permissibility of abortion arisen? There is much to suggest that it is largely the product of Catholic dogma dating back to the 1854 proclamation of the Dogma of the Immaculate Conception and the subsequent series of papal decrees (e.g. in 1884, 1889 and 1908), ‘which forbade direct termination of a pregnancy even in circumstances where, as in ectopic pregnancies, the result of non-intervention was the certain death of both mother and child’ (Badham 1987: 12).

Religious dogma aside, the question remains of: Who, if anyone, ought to be permitted to have an abortion? Under what circumstances or conditions might abortion be allowed?

Generally speaking, there are three positions that can be taken on abortion: a conservative position, a moderate position and a liberal position. These three positions (which have changed little since they were first advanced in the early 1970s and 1980s) are considered briefly below.

T he conservative position

According to the conservative position (see, e.g. Brody 1982; Noonan 1983), abortion is an absolute moral wrong, and thus something which should never be permitted under any circumstances — not even in self-defence, such as cases where a continued pregnancy would almost certainly result in the mother’s death. A common concern among conservative anti-abortionists is that, if abortion is permitted, then respect for the sanctity of human life will be diminished, making it easier for human life to be taken in other circumstances. Arguments typically raised against abortion here are almost always based on the sanctity-of-life doctrine. One example of the kind of reasoning which might be employed to argue against abortion is as follows:

It is wrong to kill innocent human beings; fetuses are innocent human beings; therefore it is wrong to kill fetuses.

(Warren 1973: 53)

Or, to use another example:

Human beings have a natural right to life; fetuses are human beings; therefore fetuses have a natural right to life and killing them is wrong.

(Pojman & Beckwith 1994)

Whether human beings do in fact have a natural right to life, and whether fetuses are in fact human beings, are matters of ongoing philosophical controversy.

T he moderate position

According to the moderate position (see, e.g. Werner 1979; Bolton 1983) abortion is only a prima-facie moral wrong, and thus prohibitions against it may be overridden by stronger moral considerations. Werner (1979), for example, argues that abortion is permissible provided that it is procured during pre-sentience (i.e. before the fetus has the capacity to feel). Since a pre-sentient fetus cannot feel, it cannot be meaningfully harmed or benefited. Thus, as with other non-sentient or pre-sentient entities, it makes no sense to say a fetus has rights, much less a right to life. In the case of post-sentience, Werner argues that abortion may still be justified on carefully defined grounds, namely: self-defence (e.g. where the life or health of the mother would be at risk if the pregnancy was allowed to continue); or unavoidability (e.g. where abortion cannot be avoided, such as in the case of ectopic pregnancy or accidental injury). Abortions performed on lesser grounds are, according to Werner, unjustified. A more recent articulation of this position similarly holds that abortion is ‘seriously wrong’, except in rare instances — for example, after rape, during the first 14 days after conception when the fetus ‘is definitely not an individual’, where the woman’s life is threatened by the continuation of the pregnancy, and where the fetus has anencephaly (Marquis 2007: 137).

Bolton (1983) takes a slightly different line of reasoning. She argues that, since fetuses are not undisputed persons, they do not have the same rights not to be killed as do actual undisputed persons. Thus, in the case of life-threatening pregnancy, at least, a woman’s right to life overrides that of the fetus. Bolton also argues, controversially, that if women are not permitted to have abortions, the community might find itself deprived of the beneficial contributions that a woman freed of the burdens of child rearing would otherwise be free to make (p 335). She concedes, however, that there are also cases ‘in which others stand to benefit from the pregnant woman’s bearing a child’ (p 337), and that this too might contribute to the community’s benefit. The bottom line of Bolton’s position is that abortion is morally permitted in some situations, and might even be ‘morally required’ in others, but it is not morally permitted in some other types of situations. Either way, the facts of the matter need to be carefully assessed and analysed before an abortion decision is made.

Another moderate argument raised in defence of abortion is that a woman is under no moral obligation to bring a pregnancy to term, particularly in instances where the pregnancy has been forced upon her (as in the case of rape), or where the pregnancy has not resulted from a voluntary and informed choice (as in cases involving contraceptive failure or ignorance). In her classic and still widely cited article ‘A defence of abortion’ (reproduced in LaFollette 2007: 117–25), Judith Jarvis Thomson (1971) contends, for example, that even if it is conceded, for the sake of argument, that a fetus is a person, this still does not place an obligation on a woman to carry it to full term. This is because morality does not generally require individuals to make large sacrifices to keep another alive. Thus, if pregnancy requires a woman to make a large sacrifice — and one which she is not willing to make — it is morally permissible for her to terminate the pregnancy.

A more recent moderate argument in defence of the permissibility of abortion takes an entirely different stance. Some philosophers, for example, have rejected the ‘competing rights’ view of the permissibility of abortion, and its basis in, what one scholar describes as, a ‘profoundly misleading view of gestation and a deontological crude picture of morality’ (Little 2007: 148). What is primarily at issue in the abortion debate, they contend, is not a ‘fetus’s rights’ or a ‘woman’s rights’ as has been conventionally argued, but having the ‘right attitude’ to parenthood and family relationships (Hursthouse 2007; Little 2007). This includes recognising that while pregnancy is one of many physical conditions a woman can experience, it does not mean it is without vice (e.g. women can be in very poor health and/or have to deal with extremely demanding circumstances that make continuing a pregnancy intolerable). In such instances, women who decide to have an abortion are not ‘self-indulgent, callous, irresponsible, or light-minded’, indeed they are often quite the opposite (Hursthouse 2007: 164).

Little (2007) takes a similar stance, arguing that abortion can be justified on grounds of ‘decency’ and the norms of ‘responsible and respectful creation’ and ‘stewardship’. By this view, a woman might choose to abort a pregnancy — not because she is selfish or irresponsible or indecent, but because her circumstances do not permit her to provide love and care to a child, or to protect a child from a life of rejection and burdensome struggle. Here the worry is ‘not that the child would have been better off never to have been born’, but were the woman to continue her pregnancy, she would violate her integrity and commitment to responsible and respectful creation and stewardship of life (p 156). Little contends that due recognition needs to be given to the fact that gestation is ‘not just any activity’, and that burgeoning human life is not just ‘tissue’ but the valuable germination of human life (p 148). Moreover, there is a ‘right way’ to value this early human life and also to value what is involved with its development and, accordingly, why abortion is both ‘morally sober and morally permissible’ (p 148). She concludes that were abortion viewed in the more contextual terms of ‘stewardship’ rather than ‘dominion’, it could be properly situated as a ‘sober matter, an occasion, often, for moral emotion such as grief and regret’, not as an act of vice. And where there is grief and regret, this should be taken as a signal ‘not that the action was indecent, but that decent actions sometimes involve loss’ (p 156).

It could, of course, be objected that the kinds of sacrifices a woman might ultimately be required to make by giving birth could be avoided by her allowing the unwanted child to be adopted. And, indeed, many view the adoption option as a respectable way out of the abortion dilemma — even in cases involving severely disabled fetuses or severely disabled newborns (see, e.g. Rothenberg 1987). Thomson, however, rejects the adoption option, arguing that it can be utterly devastating on relinquishing mothers — a claim which finds considerable support in research studies on the subject (see in particular Gillard-Glass & England 2002; Marshall & McDonald 2001; Howe et al 1992; Else 1991; Lancaster 1983; Harper 1983; Winkler & van Keppel 1983; Shawyer 1979). It can also be utterly devastating on adopted children, who may grow up ‘wondering who they are’ and spending a lifetime searching for their unknown biological parents (Lifton 1994; Strauss 1994; Health and Community Services 1992). In some countries, babies born out of wedlock (especially ‘rape babies’) can face a lifetime of shame and rejection (see in particular Doder 1993: 8). In some countries, ‘rape babies’ can even be prevented by law from being adopted. After the Bosnia war, for example, it was reported that the government of the day prohibited adoption of the children of rape victims, in the hope that their natural mothers will one day accept them (Williams 1993: 8). As these examples show, the adoption option is not as ‘simple’ as its advocates would have people believe.

T he liberal position

The third stance on abortion, the liberal position (see in particular Tooley 1972; Warren 1973, 2007; Thomson 1971), holds that abortion is morally permissible on demand. Michael Tooley (1972) argues, for example, that since fetuses are not persons, they cannot meaningfully claim a right to life. He points out that the notion ‘person’, in this instance, is a purely moral concept, and that the unfortunate tendency by some to use it as if it were synonymous with the notions of ‘human being’ and ‘human life’ is grossly misleading. Warren (1973) argues along similar lines. She contends that a fetus is not a human being and to claim that it is only begs the question. She points out that it is one thing to use human to refer ‘exclusively to members of the species Homo sapiens’, but quite another to use it in the sense of being ‘a full-fledged member of the moral community’ (p 53). In other words, it is one thing to be human in the genetic sense, but it is quite another to be human in the moral sense. These two senses are quite distinct, and care must be taken to distinguish between them. She concludes (p 53): 1

In the absence of any argument showing that whatever is genetically human is also morally human … nothing more than genetic humanity can be demonstrated by the presence of the genetic human code.

The consequence of this is unavoidable. It has yet to be demonstrated that the genetic humanity of fetuses alone qualifies them to have fully fledged membership of the moral community.

Judith Jarvis Thomson (1971) also argues that a fetus is not a person. She contends that it is nothing more than a ‘newly implanted clump of cells’. In defence of this claim, she argues that a fetus is ‘no more a person than an acorn is an oak tree’. The analogy can be extended further to show that, just as stepping on an acorn is significantly different from cutting down an oak tree, so too is aborting a fetus significantly different from killing an actual person.

The conclusion of these and similar views is that, once it is admitted that a fetus is nothing more than a clump of genetically human cells, the abortion issue becomes a non-issue. It would make no more sense to speak of the right of a fetus to life than it would be to speak of some other piece of genetically human tissue’s right to life, say, a strand of human hair or a piece of human toenail (both of which are genetically human).

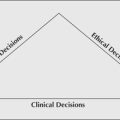

The three positions on abortion discussed so far can be expressed diagrammatically as shown here in Figure 9.1.

|

| Figure 9.1 |

A bortion and the moral rights of women, fetuses and fathers

In considering further the above three positions on abortion, it can be seen that the abortion issue rests on two key points: (1) the moral status of the fetus, and (2) the moral rights of pregnant women to control their bodies and their lives (also referred to as ‘reproductive autonomy’ [Hewson 2001]). To recap, anti-abortionists argue that the human fetus is a human being, and therefore has a right to life at least equal to that of the mother’s. Pro-abortionists, however, reject this view, arguing that, while a human fetus is genetically human, this in no way implies that it is morally a human being with a full set of rights claims. Neither, they argue, is a fetus a person. In defence of this position, pro-abortionists contend that in order for a fetus to be a person it must satisfy the moral criteria of personhood (which are very different from the criteria of fetalhood) — something that a fetus simply does not do. Let us consider this claim further.

In 1973 the reputed North American philosopher, Mary Anne Warren, argued controversially that, for an entity to be a person, it must satisfy a number of criteria, namely:

1. consciousness (of objects and events external and/or internal to the being), and in particular the capacity to feel pain

2. reasoning (the developed capacity to solve new and relatively complex problems)

4. the capacity to communicate, by whatever means, messages of an indefinite variety of types, that is, not just with an indefinite number of possible contents, but on indefinitely many possible topics

5. the presence of self-concepts, and self-awareness, either individual or racial, or both.

(Warren 1973: 55)

Warren admitted that there were numerous difficulties involved in formulating and applying precise criteria of personhood. Even so, it could be done. Commenting on the criteria she had formulated, Warren argues that an entity does not need to have all five attributes described, and that it is possible that attributes given in criteria 1 and 2 alone are sufficient for personhood, and might even qualify as necessary criteria for personhood. Given these criteria, all that needs to be claimed to demonstrate that an entity (including a fetus) is not a person is that any entity which fails to satisfy all of the five criteria listed is not a person. She concluded that if opponents of abortion deny the appropriateness of the criteria she has identified, she knows of no other arguments which would convince them. She concludes: ‘We would probably have to admit that our conceptual schemes were indeed irreconcilably different, and that our dispute could not be settled objectively’ (Warren 1973: 56).

Michael Tooley (1972), like Warren, also interpreted ‘person’ in rationalistic terms. He argued that in order for something to be a person it must have a serious moral right to life. And in order to have a serious moral right to life, it must possess ‘the concept of self as a continuing subject of experience and other mental states, and believe that it is itself such a continuing entity’ (p 44). Since fetuses do not satisfy this basic ‘self-consciousness requirement’, as Tooley called it, they are not persons — they do not have a serious moral right to life, and therefore to kill them is not wrong.

More recently, in a revised version of her earlier work, Mary Anne Warren (2007) expands on and refines the characteristics which she believes are central to the concept of personhood, namely:

1. sentience — the capacity to have conscious experiences, usually including the capacity to experience pain and pleasure;

2. emotionality — the capacity to feel happy, sad, angry, loving, etc.;

3. reason — the capacity to solve new and relatively complex problems;

4. the capacity to communicate, by whatever means, messages of an indefinite variety of types; that is, not just with an indefinite number of possible contents, but on indefinitely many possible topics;

5. self-awareness — having a concept of oneself, as an individual and/or as a member of a social group; and finally

6. moral agency — the capacity to regulate one’s own actions through moral principles or ideals.

(Warren 2007: 130)

Although conceding that it is difficult to define these traits precisely, or to specify ‘universally valid behavioural indications that these traits are present’, Warren (1997: 84) nevertheless holds that these criteria of personhood are functional — pointing out that an entity ‘need not have all of these attributes to be a person’. She explains:

It should not surprise us that many people do not meet all the criteria of personhood. Criteria for the applicability of complex concepts are often like this: none may be logically necessary, but the more criteria that are satisfied, the more confident we are that the concept is applicable. Conversely, the fewer criteria are satisfied, the less plausible it is to hold that the concept applies. And if none of the relevant criteria are met, then we may be confident that it does not [apply].

(Warren 1997: 84)

Warren (1997) suggests that in order to demonstrate that a fetus is not a person, all that is required is to claim that a fetus has none of the above six characteristics of personhood.

For some, the personhood argument does little to settle the abortion question. For example, it might be claimed that, even if it is true that a fetus is not a person, it nevertheless has the potential to become one, and therefore it has rights (see also Warren 1977). Thus abortion is still wrong on the grounds of the potentiality of the fetus (Glover 1977: 122). Or, to borrow from Warren’s analogy cited earlier: even though an acorn is not an oak tree, it nevertheless has the potential to become one; therefore crushing an acorn is tantamount to chopping down an oak tree.

There are a number of obvious difficulties with this view. First, the argument tends to presume that what is potential will in fact become actual. In the case of zygotes, however, this is quite improbable. As Engelhardt points out, only ‘40–50% of zygotes survive to be persons (i.e. adult, competent human beings)’ (1986: 111). It might then be better, suggests Engelhardt, to speak of human zygotes as being only ‘0.4 probable persons’.

Second, the argument strongly suggests that it is not the fetus per se that is valued, but rather what it will become (Glover 1977: 122). It is difficult to interpret just what kind of moral demand this creates. As Glover points out (p 122):

It is hard to see how this potential argument can come to any more than saying that abortion is wrong because a person who would have existed in the future will not exist if an abortion is performed.

If we take the potentiality argument to its logical extreme, we are committed to accepting, absurdly, that contraception, the wasteful ejaculation of sperm, menstruation and celibacy are also morally wrong, since these too will result in future persons being prevented from existing (Warren 1977: 277).

The main unresolved question, however, is: Can a potential person be meaningfully said to have actual rights and, if so, can these rights meaningfully override the existing rights of actual persons? Or, to put this another way: Can a fetus (a potential person) have actual rights and, if so, can these meaningfully override the existing rights of its mother (an actual person)? The crux of the dilemma posed here is whether the more immediate and actual rights of the pregnant woman should be recognised before the more remote and potential needs of the fetus, or vice versa.

One answer is that, given our understanding of the nature of moral rights and correlative duties, there is something logically and linguistically odd in ascribing rights to fetuses (non-persons), particularly during the pre-sentient stage. If we were to accept that non-sentient fetuses have moral rights, we would be committed, absurdly, to accepting that all sorts of other non-sentient things have moral rights — including human toenails, strands of hair or pieces of skin. For argument’s sake, however, let us accept that the fetus does have moral rights and, further, that these can meaningfully conflict with the mother’s moral rights. The question which arises here is which fetal/maternal rights are likely to conflict?

The most obvious is the fetus’ and the mother’s common claim to a right to life. This is particularly so in cases where the mother’s life would almost certainly be lost if the pregnancy were allowed to continue. In such situations it seems reasonable to claim that the mother’s right to life must at least be as strong as the fetus’ right to life. And, further, since both stand to die unless the pregnancy is terminated, then surely it is better, morally speaking, that only one life is lost instead of two? It is difficult to see how anyone could reasonably and conscientiously choose an outcome which would see both the mother and the fetus die. Furthermore, as stated elsewhere in this book, morality does not generally require us to make large personal sacrifices on behalf of another, and thus it would be morally incorrect to suggest that the mother has a duty to sacrifice her life in defence of the fetus. In the case of life-threatening pregnancies, then, it seems reasonable to conclude that the pregnant woman’s right to life has the weightier claim.

A second set of rights which may conflict is the mother’s right to have control over her body and life’s circumstances versus the fetus’ right to life. It might be claimed, for example, that a woman’s right to choose her lifestyle, career, economic circumstances, standard of health, and similar, override any claims the fetus might have to be ‘kept alive’. The mother may then withdraw her ‘life support’ even if this means the fetus will die in the process (an unfortunate, but nevertheless unavoidable, consequence). Against this, however, it might still be claimed that the inconveniences and other psychological, physical or social ills caused by an unwanted pregnancy are still not enough to justify killing the fetus and violating its right to life (Brody 1982; Noonan 1983). The demand not to kill the fetus becomes even more persuasive when it is considered that there are alternatives available for helping to prevent or alleviate the ills of unwanted pregnancies, such as child welfare and other social security benefits, adoption, counselling, medication, or, ectogenesis, that is, extracting the embryo or fetus and placing it in a surrogate or an artificial uterus (Coleman 2004; Gelfand & Shook 2006). In the case of the latter, it should be noted that this proposal is not as far-fetched as it might seem and can no longer be dismissed as ‘just the stuff of science fiction’. Ectogenesis is already used in experimental animal science (Adinolfi 2004). And although the technical problems remain formidable, some scientists have predicted that efficient artificial uteri in humans could be available as soon as 2009 — especially for late-term fetuses where it would be easier to connect embryonic umbilical arteries and veins to equipment designed to pump, filter and nourish blood (Adinolfi 2004). Research has already been carried out on ‘maintaining uteri extracted from women outside of a woman’s body’, and implanting embryos into these wombs (Rowland 1992: 288–9). Moreover, aborted fetuses have been ‘kept alive for up to forty-eight hours’ in these research projects (Rowland 1992: 289; see also Caplan et al 2007; Coleman 2004; Gelfand & Shook 2006). In light of these alternatives (notwithstanding the complex ethical issues raised by ectogenesis in particular), some critics contend that the claim a mother’s rights ought to be given overriding consideration over those of the fetus becomes increasingly difficult to sustain.

A third set of rights which might conflict is the mother’s right to health (and to a quality of life) versus the fetus’ right to life. In this instance, the mother’s health and quality of life are threatened not by her pregnancy but by a progressive debilitating disease, such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s or diabetes. The mother might, for example, contemplate getting pregnant for the sole purpose of growing tissue which can be harvested and transplanted into her brain or pancreas in an attempt to restore her health. The issue of fetal tissue transplantation has long been the subject of intense debate (Engelhardt 1989). Although governments are striving hard to prevent this type of scenario from occurring, there have already been cases of women getting pregnant and having abortions for the sole purpose of supplying fetal tissue for transplantation — if not for themselves, for others including a fetus’ siblings (see, e.g. Gibbs 1990a; Martin et al 1995; Morrow 1991).

A fourth set of rights which may cause conflict involves not only the competing claims of a fetus and its mother, but also those of the father (also called ‘male abortion’) (McCulley 1988; Purdy 1996; Teo 1975). During the 1980s there was a number of legal cases (notably in the United Kingdom (UK), the United States (US), Canada and Australia) involving fathers undertaking legal action in an attempt to stop their (ex-)wives and (ex-)girlfriends from having abortions (AFP 1989; Beyer 1989; Lowther 1988; PA 1987; Leo 1983; McCulley 1988; see also Forrester & Griffiths 2005: 192). In 1987, for example, a 23-year-old father was reported to have taken court action in an English court of appeal to try and stop his 21-year-old girlfriend, an Oxford University student, from having an abortion (PA 1987: 6). The court was reported to have rejected the father’s appeal — significantly, not on the grounds of the woman’s right to choose, but on the grounds that the fetus was (PA 1987: 8):

… so underdeveloped that, if separated from its mother, it would be unable to breathe either naturally or through a ventilator, it was not capable of being ‘born alive’.

Upon learning of the court’s decision, the solicitor for the 21-year-old Oxford University student is reported to have stated (PA 1987: 8):

It is her decision what she does now, but it is a point of principle that she is now able to control her own body.

The 23-year-old man responsible for her pregnancy is reported to have been ‘disappointed and very surprised at the result’ (PA 1987: 8).

A year later, a similar case occurred in the US. It involved a 24-year-old man who was reported to have ‘lost a lower-court appeal for the right to force his estranged [19-year-old] wife to have their baby’ (Lowther 1988: 8). The court was reported to have ruled against the father, on the grounds that the abortion concerned only the estranged wife (p 8). Rejecting the court’s decision, the man decided to ‘fight to seek a legal precedent’ in favour of fathers — even though his estranged wife had gone ahead and had an abortion after the court’s findings. In explaining his decision to take further legal action, the man was reported to have said (p 8):

I was willing to take full responsibility and raise the baby and take care of it; there’s nothing for me to do now but let the wounds heal. Maybe the next guy will have it easier.

Critics of his stance, and advocates of a woman’s right to choose, argued, however, that ‘it is nothing short of involuntary servitude to order a woman to carry a child she does not want’ (Lowther 1988: 8). Against this, an Indiana lawyer argued in support of the man’s actions that what they were asking the court to do was merely (p 8):

… to find that there should be a balancing of the interests of the father against those of the mother on a case-by-case basis.

In 1989, 1 year later again, a similar case was reported in Canada. This time it involved a 25-year-old man who took court action to stop his 21-year-old ex-girlfriend from having an abortion (Beyer 1989). The case took a dramatic twist, however, when, with considerable embarrassment, the woman’s lawyer announced, before the court case had concluded and all arguments completed, that his client, ‘worried that it might be too late for an abortion, even if she won the case, had decided not to wait’ (Beyer 1989). Commenting on the case, Beyer writes (p 60):

Defying a lower-court injunction, she had gone ahead with the operation. The court was stunned. But it went on nonetheless to rule unanimously that the injunction barring the abortion was invalid. The court thus seemed to be ending a recent spate of injunctions against abortion sought by angry ex-boyfriends.

Not surprisingly, these cases have been viewed with little sympathy from women who historically have been left alone with the burden and hardships of child rearing after the fathers of their children have long abandoned them. Some even worry that, if the paternity rights debate is allowed to progress to its logical extreme, it could have paved the way for even rapists to prevent their victims from having abortions, and to press for access rights after the baby has been born. It has also been suggested that recognition of paternal rights may see the courts inviting rapists ‘to be present at the birth’ (Rogers 1992).

Just what the ultimate outcome of the ‘mothers’ rights versus fathers’ rights’ debate will be, remains an open question. To date, the courts in Australia and the UK have not recognised the ‘rights’ of fathers either to be consulted about a termination of pregnancy or to enforce the rights of an unborn child to be protected against abortion (Forrester & Griffiths 2005). In the US, however, a very different situation exists. As Hadley reports (1996: 74):

the question of spousal consent to abortion has rumbled around for a considerable time, and a number of states have tried to make spousal consent or notification part of their abortion law.

This is an issue which is not going to go away.

A bortion, politics and the broader community

The abortion issue is extraordinarily complex; it is also extremely political, as some spectacular overseas incidents have shown. For example, in 1990, Belgium was thrown into a constitutional crisis after King Baudouin, Belgium’s reigning monarch, stepped down from his throne temporarily ‘because his conscience would not let him sign a law legalising abortion’ (Reuters 1990a: 7). As a result, the government had to take over the King’s powers and pass the abortion law. It is reported that once the abortion law was passed the King’s inability to reign ceased, and he resumed his position on the throne (Reuter 1990a: 7).

In the same year, it was reported that disagreement over abortion law threatened to ‘derail a treaty on German unity’ (Reuter 1990b: 7). The disagreement was primarily over whether ‘West German women may take advantage of East Germany’s liberal abortion laws after unification’ (Reuters 1990b: 7).

In 1992, Ireland (where abortion is illegal) witnessed political uproar and large public demonstrations after the High Court banned a 14-year-old rape victim from travelling to Britain for an abortion (the girl had been raped repeatedly by a friend’s father over a 1-year period) (Barrett 1992c, 1992d; Holden 1994). It was reported that many European constitutional lawyers considered the ban a breach of the Treaty of Rome, which had brought the European Community (EC) into being almost four decades earlier, and, among other things, ‘permitted the right to free movement within the EC’ (Barrett 1992c). The situation reached crisis point when it was evident that the ban threatened the European Community’s Maastricht Treaty on European political union, which Irish voters were due to vote on a few months later ( Independent 1992: 6; Barrett 1992a, 1992b, 1992f).

The case is reported to have aroused the concerns of a number of influential groups, including Irish legislators and lawyers and members of human rights and women’s groups, and to have raised serious questions about how far the state and its officials should interfere in the fundamental rights of its citizens ( Independent, New York Times 1992: 9). The travelling ban was eventually lifted by the Supreme Court in Dublin, and the girl was able to travel to Britain for an abortion ( Independent 1992: 6). Later in the year, two Dublin counselling clinics appealed successfully to the European Court of Human Rights against the Irish Government’s prohibition on women gaining access to information about abortion services overseas (Barrett 1992e: 8; Holden 1994). The judges who heard the case are reported to have decided that the Irish Government was ‘violating fundamental human rights by preventing women from gaining access to information about having abortions abroad’ (Barrett 1992e: 8). The counselling clinics were also reported to have been awarded costs and damages of more than $400000 (Barrett 1992e: 8).

In 2007, Ireland’s abortion laws once again threatened to erupt into a political crisis when a pregnant 17-year-old began court proceedings to enable her to travel to Britain for an abortion. The teenager decided to have an abortion upon learning that the fetus she was carrying had a rare brain condition (anencephaly) and was not expected to live longer than a few days after being born (Bowcott 2007: 14). Although abortion is still illegal in Ireland (and is also the subject of a constitutional ban), it may be performed in cases where the risks to the mother are substantial. Neither the law nor the constitution allow abortion to be performed on grounds of fetal abnormality, however, and it was this point that threatened to cause a constitutional crisis. The case is reported to have prompted ‘fresh calls for constitutional reform’ and for the provision of ‘safe, free, and legal abortion in Ireland’ (Bowcott 2007: 14).

Abortion was also a major issue in the American presidential election of 1992, with the then presidential contenders Bill Clinton and Ross Perot both trying ‘to lure pro-choice voters to their side’ (Barrett, L I 1992: 54). During the campaign, the Bush camp (whose law reforms saw the loss of civil rights protection for US abortion clinics [ Baltimore Sun 1993] and the banning of abortion counselling at federally funded clinics [Toner 1993]) admitted publicly that anything raising the profile of the abortion issue was ‘a problem for us’ (Barrett, L I 1992: 54). Initially, the Clinton camp also wanted to avoid too much attention being paid to the abortion issue. It was reported that basically ‘he wanted to avoid the appearance of catering to “special interests”, including feminists’ (Barrett, L I 1992: 55).

The abortion debate in the US took a dramatic and historic turn in 1993, when an anti-abortion protester shot and killed a doctor during a pro-life demonstration outside a lawful abortion clinic (Rohter 1993: 7; see also Hadley 1996). Abortion rights groups took the shooting of the doctor as a ‘symbol of the increasing harassment’ of health workers involved in abortion work, and which has since seen abortion clinics increasingly vandalised and destroyed by arsonists.

According to Robinson (2004) of Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance, since harassment and violence first began to be levelled at abortion clinics in the early 1970s, there have been literally tens of thousands of incidents directed against abortion clinic personnel. Citing US National Abortion Federation figures, Robinson estimates that in the 16-year period from 1989 to 2004, anti-abortion protesters were implicated in 24 murders and attempted murders; 180 (actual or attempted) bombings and arson attacks; 3349 incidents of invasion, assault and battery, vandalism, trespassing, death threats (including over 554 Anthrax hoaxes), burglary and stalking; 11448 instances of hate mail, harassing phone calls and bomb threats; 516 blockades; and 80305 episodes of picketing across the US (Robinson 2004). Although the number of seriously violent crimes against abortion clinics is believed to have decreased in recent years, a survey of 361 abortion clinics in 48 US states has revealed that, of those who responded, 7% were the targets of major violence, 9% the targets of minor violence, 7% were the victims of major vandalism, 27% minor vandalism, and 44% the victims of harassment (Pridemore & Freilich 2007). In some jurisdictions, because of safety fears, doctors who perform abortions ‘wear bullet-proof vests as they journey to work’ (Hadley 1996: xi).

Closer to home, Australia has also experienced the politicisation of abortion, with a small number of politicians attempting, unsuccessfully, to introduce legislation aimed at restricting abortion services for women. In 1988, for example, the Reverend Fred Nile, a New South Wales independent member of parliament, attempted unsuccessfully to introduce his Unborn Child Protection Bill, which could have seen doctors who performed abortions jailed for up to 14 years and fined $100000 (Ansell 1988: 21). Reverend Nile was reported to have said that the Bill would allow abortion only if the mother’s life was in danger, and that ‘no exceptions would be made for any threat to the mental health of the mother’ (p 21). The medical director of the Family Planning Association of New South Wales is reported at the time to have condemned the Bill on the grounds that it would ‘not stop women having abortions — it would just drive them underground’ (p 21).

Alistair Webster (a Liberal politician in New South Wales) has also made several attempts over the years to introduce legislation aimed at eliminating Medicare rebates for abortion services. An attempt in 1990 was condemned by the Women’s Electoral Lobby, who reminded politicians supporting the move that ‘no legislation has ever prevented desperate women from terminating unwanted pregnancies’ (Schnookal 1990: 2). Further, as one ALP member responded during parliamentary debate on the matter:

Medicare benefits do not cause abortion. It will not go away if we remove the benefit, just as unemployed people will not disappear if we remove the unemployment benefit … The best way to reduce abortion numbers is better sex education, family planning and support for pregnant women — from their partners and from the government.

(Dr Ric Charlesworth, cited by Wainer 1990: 8)

In 1998, however, the abortion debate reached a new dimension in Australia when Western Australian politicians voted in favour of legislation regarded as creating Australia’s ‘most liberal abortion laws’ (Reardon 1998: 7). The legislation (introduced by Labor MLC Cheryl Davenport, and ratified by the upper house of parliament within weeks of passing through the lower house) repealed ‘criminal sanctions against women for procuring an abortion’ (Le Grand 1998: 1; see also Ewing 1998: 3; Reardon 1998: 7). The legislation was reported as leaving a woman’s informed consent as the ‘minimum requirement for doctors to perform lawful abortion’ — literally, abortion on demand (Le Grand 1998: 11). It was speculated at the time that the abortion law reforms in Western Australia would ‘trigger a review of abortion laws’ in other Australian states (Ewing 1998: 3). Four years later, the Australian Capital Territory removed abortion from the Criminal Code.

Arguably the most dramatic event to occur in Australia’s abortion history, however, occurred in July 2001 when Steve Rogers, a security guard at the Fertility Control Clinic in East Melbourne, was fatally shot by a man intent on destroying the clinic (Dean & Allanson 2003). This attack, the first of its kind in Australia, sparked fury and dismay at the vulnerability of abortion clinic personnel and the failure by law enforcement bodies to protect those attending and working at such clinics (Dean & Allanson 2003; Rees & Head 2001). Significantly, in 2006, another man attempted to kill — and was subsequently charged with threatening to kill — another security guard at the clinic, underscoring the risks and potential threats to the safety of abortion personnel in Australia (Nader 2007) and the tensions that exist between the right to access and the right to protest abortion (Dean & Allanson 2003).

At a broader international level perhaps one of the most controversial examples of an attack on abortion has come from Pope John Paul II (circa 1920–2005). In February 1993, the Pope is reported to have told Bosnian women who were pregnant as a result of wartime rape that ‘they should not seek abortions, but give birth to the children’ ( Bioethics News 1993: 3; see also Kissling 1999; Nikolic-Ristanovic 1999). It is estimated that between 20000 and 70000 women had been raped — the majority of violated women being Muslims (Corlett 1993: 4). It is reported that the Pope addressed the women in a letter as follows: ‘Do not abort. Your children are not responsible for the ignoble violence you have undergone’ ( Bioethics News 1993: 3). He asked the women to ‘accept the enemy’ into them, and make him the ‘flesh of their own flesh’ (Kissling 1999: 12).

The Pope’s comments subsequently became the subject of much criticism by Muslims and Catholic theologians alike. One outspoken German Catholic theologian (a woman) is reported to have said that the Pope ‘had no right to get involved in matters of which he can have no understanding’ and that ‘no bachelor … could decide on matters such as these. A decision can be made only by those who have been raped’ ( Bioethics News 1993: 3).

There remains much more to be said on the politics of and the moral controversies surrounding abortion than there is space here to do. For example, we have yet to address the problems of:

▪ restrictive abortion laws and the real suffering these have caused — and continue to cause — girls and women who find themselves trapped by an unwanted and/or intolerable pregnancy (see, e.g. the Bobigny case [Henderson 1975], the Roe v Wade case [McCorvey 1994], the Irish ‘X’ case [Holden 1994] and Messer & May’s [1988] Back rooms: voices from the illegal abortion era)

▪ sex-selected abortions, practised widely in countries where a patriarchal and misogynist preference for sons results in the sex-selected abortions of female fetuses (a form of gendercide) in those countries (see, in particular, Mary Anne Warren’s [1985] Gendercide: the implications of sex selection)

▪ homophobic-selected abortions — otherwise referred to as ‘gay gene abortions’ — proposed in the event of a ‘sexuality gene’ being discovered (it has been seriously suggested by a leading geneticist and Noble laureate that if a gay gene is discovered, and a fetus is found to be ‘gay-gene identified’, a mother ought to have the option of aborting a fetus if ‘she doesn’t want a homosexual child’ [Loudon & Wilson 1997; Joyce 1997]

▪ rape abortions, and the dilemmas associated with terminating pregnancies resulting from rape and sexual abuse (see also Holden 1994)

▪ eugenic-abortions, and the dilemmas associated with aborting fetuses with disabilities ranging from the very minor to the extremely severe (for instance, there is both formal and anecdotal evidence that fetuses have been aborted for relatively minor ‘cosmetic’ deformities, for example, having one leg shorter than the other, or having a cleft lip [Hager 2002])

▪ the role of ‘fetal police’ (comprised of registered medical practitioners, ‘risk managers’, legislators, lawyers and judges) who take steps to coerce, detain and even incarcerate women who engage in health-injurious behaviours (such as cigarette smoking, illicit drug taking, alcohol consumption, and the like) during pregnancy (see, in particular, Ruth Macklin’s [1993] discussion on ‘The fetal police: enemies of pregnant women’ included as Chapter 4 of her text Enemies of patients; Cave 2004; Gallagher 1995; Hadley 1996; Meredith 2005; Pojman & Beckwith 1994)

▪ the nature and implications of the ‘hard choices’ women have to make when choosing abortion (Cannold 1998; Hadley 1996), and, not least,

▪ the traumatic emotional and physical consequences to women of having abortions, including the terrible complications that abortion procedures themselves can have such as haemorrhage, uterine perforation, sepsis, kidney failure, coma and death (Cannold 1998; Grimes et al 2006; Little 2007; Meredith 2005; Singh 2006; WHO 2007b).

Other problems yet to be examined include the following:

▪ determining the point at which a fetus actually becomes a person — for example, is it at conception/syngamy, upon achieving viability, or at birth? (see also Gillon 2001; Kissling 2001; Buckle & Dawson 1988; Warren 1988; Glover 1977: 123–6)

▪ ‘slippery slope’ arguments which reason that, if abortion is permitted, our moral characters and expectations will seriously decline; that is, if we allow abortion today, we will allow infanticide tomorrow and the next day we will allow euthanasia of other ‘useless’ persons.

Unfortunately, for reasons of space and time, consideration of these and similar problems must be left for another time.

C onclusion

As has been shown by the discussion advanced in this chapter, abortion is a highly complex and controversial issue, and one which is unlikely to be resolved to the satisfaction of all the parties involved. This means that nurses will invariably encounter moral disagreements in abortion contexts — many of which may not be able to be reconciled. The discussion here also warns the nursing profession that it cannot afford to be complacent or indecisive about developing a formal (policy) position on abortion practices and procedures, or the questions of social justice these raise. Equally important, the discussion here demonstrates the need for the abortion issue to be opened up for formal and informed discussion within the ranks of the nursing profession. It can never be assumed that nurses have had a trouble-free path to conscience-free participation in abortion work. If we do not know what experiences nurses have had in this area, we will never be in a position to advance a nursing perspective on the moral permissibility of abortion, much less on the extent to which nurses can be reasonably expected — against their moral conscience, and also against their emotional health — to assist (or not assist, as the case may be) with abortion work. In formulating policies on the abortion issue, however, the nursing profession must be careful not to lose sight of its moral commitment to respecting women’s personal choices (no matter how disagreeable these might appear to be). Individual nurse clinicians, meanwhile, must take care not to fall into the moralising trap of imposing their personal values on others — in this instance, women who have decided, for whatever moral reason, to abort a pregnancy which, if carried to full term, promises intolerable consequences. The point remains, however, that so long as the nursing profession remains indecisive about reaching a just position on the subject, women contemplating abortion will not be able to rest assured that they will receive safe and quality nursing care before, during and after an abortion procedure. Nurses choosing to work in abortion services, meanwhile, will continue to carry the emotional burdens of their distressing work silently, personally, and without the level of professional support that their peers receive in other (‘more acceptable’) distressing areas.

Case scenario 1

In 2001, a public health nurse who had been employed by a local US department of health from 1990 until 2001 lost her job ostensibly because of her deeply held religious belief that life begins at conception (Rutherford Institute 2002). Early in her employment, the nurse advised her supervisors of her religious opposition to abortion and requested not to be assigned to duties that required her to discuss with or provide advice on abortion to her patients. During the first 5 years of her employment, the nurse’s supervisor accommodated her requests and she was permitted to refer patients wanting the ‘morning after pill’ as an emergency contraception or information about abortion to other nurses. During this time, the nurse provided high-quality care to women who were regarded as having ‘high-risk pregnancies’ as well as education on how to improve the health of their pregnancies (Rutherford Institute 2002). In 1995, however, a new supervisor was appointed who was less tolerant of the nurse’s anti-abortion stance and was even openly critical of her for her views. The supervisor subsequently advised the nurse that, due to budget cuts, her position in the department was going to be cut and that if she wanted another position ‘she would have to be willing to dispense emergency contraception’ (Rutherford Institute 2002). After this, the nurse’s position was cut and, because of her unwillingness to work in an area that required her to dispense emergency contraception (and that could also act as an abortifacient), she was left without a job.

Case scenario 2

Nursing and midwifery staff involved in an abortion procedure carried out at a private hospital were astonished to discover that the expelled fetus, which was of 21–22 weeks’ gestation, ‘cried and moved and had an obvious heartbeat’ upon delivery (Schulz 1999: 2). A nurse subsequently contacted the doctor on call advising him that the abortion procedure had resulted in a ‘live birth’. Because the fetus was regarded as being of a ‘non-viable age’, however, the doctor allegedly advised that nothing further needed to be done. Since the fetus was not expected to live, it was covered in a stainless steel dish without medical attention. It was claimed that the fetus lived for 80 minutes after being aborted (Schulz 1999: 2). The staff involved were distressed about the situation and reported it to hospital management. The case later became the subject of a coronial inquiry to determine ‘why no care was given to a baby who obviously was alive’ (Schulz 1999: 2). The coroner was reported to have clarified that ‘the inquest was not concerned with the rights and wrongs of abortion. It was about the child’s rights during the 80 minutes it lived’ (Schulz 1999: 2). (See also legal cases of fetuses ‘born alive’ in Cave 2004; Meredith 2005.)

CRITICAL QUESTIONS

1. Is it reasonable for nurses who are opposed to abortion work to seek employment in organisations that provide abortion services?

2. In instances in which abortion procedures result in the delivery of a ‘live birth’ (an outcome that is not uncommon with late trimester abortions), what actions would you take and why?

3. In what circumstances might a nurse validly claim a ‘right’ to refuse to provide advice on and/or assist with abortion work and, conversely, a ‘duty’ to refuse?

4. What, if any position, should the nursing profession take on the abortion issue?

Endnote

1. Copyright © 1973, The Monist, La Salle, II 61301. All quotations from this work are reprinted with permission.