CHAPTER 13. Taking a stand: conscientious objection, whistleblowing and reporting nursing errors

L earning objectives

▪ Discuss critically the nature of conscience and its role in guiding ethical nursing conduct.

▪ Outline five conditions that must be met in order for a claim of conscientious objection to be genuine.

▪ Examine critically arguments both for and against the view that nurses ought to be permitted to conscientiously refuse to participate in certain procedures in nursing and health care contexts.

▪ Define whistleblowing.

▪ Discuss the possible adverse consequences to nurses of blowing the whistle in health care.

▪ Examine critically the conditions under which whistleblowing in health care might be justified.

▪ Define nursing error.

▪ Discuss critically the ethics of reporting nursing errors.

▪ Discuss the practical and ethical implications of taking a non-punitive approach to nursing error management.

I ntroduction

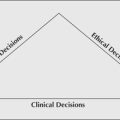

At some time during the course of their professional practice there will come a time when nurses must take a stand on what they consider, after careful thought and critical reflection, to be morally important. Taking a stand can involve either individual or collective action. Individual action may involve a nurse refusing conscientiously to participate in a controversial medical or nursing procedure; reporting an error, adverse event or some other troubling incident to a supervisor, an oversight unit or to some other authority (including an external statutory authority); seeking advice from a clinical ethics committee or some other decision-making committee; or speaking out in either a conference or some other public forum. On rare occasions, a nurse might decide to approach media outlets to have his or her concerns aired. Collective action, on the other hand, may involve groups of nurses embarking on an organised lobbying campaign aimed at particular target groups. Or, as has become increasingly common around the world, it may involve strike action — particularly in situations involving substandard working conditions that are placing patient safety at risk (see, e.g. Johnstone 2002a, 1999a; Salladay 2002).

Whatever action is taken, it is never free of moral risk. There are many examples in the nursing, legal and bioethics literature (too numerous to list here) of nurses having suffered both personally and professionally because they took a stand on what they deemed to be an important professional or moral issue. For example, nurses conscientiously refusing to participate in certain morally controversial medical procedures have sometimes lost their jobs or have been made to resign ‘voluntarily’ (some examples of which will be given shortly).

Despite the associated hazards and risks, nurses have a moral obligation to take a stand on important ethical issues. Nevertheless, there are some misconceptions about the nature of this obligation, the options open to nurses for taking a stand, and even about whether it is right to take a stand at all. Some nurses even fear that some of the options open to them are incompatible with their broader professional obligations as nurses and are therefore ‘unprofessional’. For some nurses this has caused enormous personal conflict, and has served more to compound the moral problems they face in the workplace than to help resolve them.

This chapter attempts to clarify some of the confusion surrounding various options open to nurses for taking a stand on a moral issue, and to show that these options might not only be compatible with professional nursing obligations, but may even be prima-facie professional nursing obligations in themselves. It is to discussing the particular options of conscientious objection, whistleblowing and reporting nursing errors that this chapter now turns.

C onscientious objection1

Nurses have been ‘conscientiously objecting’ to workplace practices and related processes for years (e.g. by sidestepping a particular patient assignment, changing shifts, declining to work in a particular ward or area, or taking a ‘sick day’ off work). Their objections, however, have rarely gained public attention. Indeed, it has only been in extreme situations, such as when a nurse has been dismissed or denied employment, or has been threatened in some way, have issues involving conscientious objection come to the attention of others outside of the unit or organisation where they have arisen. Those who have had the courage to formally voice their conscientious refusal to participate in certain medical procedures or organisational processes, or to carry out certain directives given by an employer or superior, have sometimes done so at great personal and professional cost. One of the most famous examples of this can be found in the much-cited United States (US) case of Corrine Warthen.

Corrine Warthen, a registered nurse of many years experience, was dismissed from her employing hospital of 11 years for refusing to dialyse a terminally ill bilateral amputee patient. Warthen’s refusal in this instance was based on what she cited as ‘ “moral, medical and philosophical objections” to performing this procedure on the patient because the patient was terminally ill and … the procedure was causing the patient additional complications’ ( Warthen v Toms River Community Memorial Hospital (1985: 205).

Warthen had apparently dialysed the patient on two previous occasions. In both instances, however, the dialysis procedure had to be stopped because the patient suffered severe internal bleeding and cardiac arrest ( Warthen’s case 1985: 230). It was the complications of severe internal bleeding and cardiac arrest that she was referring to in her refusal. Her dismissal came when she refused to dialyse the patient for a third time.

Believing she had been wrongfully and unfairly dismissed, Warthen took her case to the Supreme Court, where she argued in her defence that the Code for Nurses of the American Nurses’ Association (ANA) justified her refusal, since it essentially permitted nurses to refuse to participate in procedures to which they were personally opposed ( Warthen’s case 1985: 229).

The court did not find in her favour, however, and she lost her case. In making its final decision, the court made clear its position on a number of key points ( Warthen’s case 1985):

1. An employee should not have the right to prevent his or her employer from pursuing its business because the employee perceives that a particular business decision violates the employee’s personal morals, as distinguished from the recognised code of ethics of the employee’s profession … (p 233).

2. [In support of the hospital’s defence] it would be a virtual impossibility to administer a hospital if each nurse or member of the administration staff refused to carry out his or her duties based upon a personal private belief concerning the right to live … (p 234).

3. The position asserted by the plaintiff serves only the individual and the nurses’ profession while leaving the public to wonder when and whether they will receive nursing care … (p 234).

Another famous example of the personal and professional cost a nurse can pay for taking a stand on an issue can be found in the case of Frances Free (also from the US). Free, an experienced registered nurse, was dismissed by her employer after she had refused to evict a seriously ill bedridden patient. Free’s refusal ( Free v Holy Cross Hospital (1987): 1190), in this instance, was based on grounds that to evict the patient would have been:

in violation of her ethical duty as a registered nurse not to engage in dishonourable, unethical, or unprofessional conduct of a character likely to harm the public as mandated by the Illinios Nursing Act.

The female patient in question had been arrested for possession of a hand gun. Meanwhile, an ‘order’ had been given for the patient to be transferred to another hospital. The police officer guarding the patient pointed out, however, that because of certain outstanding matters, the other hospital would probably not accept the patient and it was likely that she would be returned to Holy Cross Hospital. Free communicated this information to the hospital’s chief of security who responded by telling her that the patient was to be removed from the hospital ‘even if removal required forcibly putting the patient in a wheelchair and leaving her in the park’ which was across the road from the hospital ( Free’s case: 1189). Although Free disagreed with removing the patient, she gave the necessary instructions for the patient’s transfer to the other hospital.

As part of the process of dealing with this situation, Free contacted the vice-president of her employing hospital to discuss the matter with him. It is reported that the vice-president ‘became agitated, shouted and used profanity in telling Free that it was he who had given the order to remove the patient’ ( Free’s case: 1189). After this incident, Free contacted the patient’s physician who stated that ‘he opposed the transfer’ and instructed Free ‘not to touch the patient but to document his order that the patient should remain at the hospital’ (p 1189). After checking the patient and ‘calming her down’, Free received a telephone call ‘ordering her to report to the office of the vice-president’. When she arrived at the vice-president’s office Free was advised ‘that her conduct was insubordinate and that her employment was immediately terminated’ (p 1189). Free subsequently took court action arguing that her dismissal was ‘unfair’. Free lost her case, however. Significantly, during the court proceedings, Free’s actions were characterised ‘as being of a personal as opposed to a professional nature and therefore as falling outside the scope of the Illinios Nursing Act’ (Johnstone 1994: 256).

These and similar cases demonstrate that the issue of conscientious objection by nurses is by no means trivial and deserves sustained attention by all concerned (e.g. see also the case of the public health nurse who ostensibly lost her job because of her conscientious objection to abortion and working in an area that required her to administer emergency contraceptives and abortifacients, presented as case scenario 1 in Chapter 9 of this book). In particular, attention needs to be given to clarifying the nature and authority of conscience, distinguishing between genuine and bogus claims of conscientious objection, and determining the kinds of policy there should be towards those who conscientiously refuse to perform or to participate in morally controversial medical and/or nursing procedures. As well as this, attention needs to be given to the question of: When, if ever, can a superior decently direct nurses to perform tasks which they are conscientiously opposed to performing? An additional question is: Can nurses decently refuse to assist with tasks which others do not regard as morally problematic? These and other key concerns raised by the conscientious objection debate are addressed in the following sections.

T he nature of conscience explained

The Oxford English Dictionary (2003) defines ‘conscience’ as:

the internal acknowledgment or recognition of the moral quality of one’s motives and actions; the sense of right and wrong as regards things for which one is responsible; the faculty or principle which pronounces upon the moral quality of one’s actions or motives, approving the right and condemning the wrong.

The Collins English Dictionary (2005) defines ‘conscience’ as a ‘sense of right and wrong that governs a person’s thoughts and actions’. These definitions, however, are inadequate to answer questions concerning the legitimacy and power of conscience as a bona fide moral authority. In short, while they help to describe what conscience is, these definitions say nothing about whether individuals should always obey their conscientious senses of right and wrong, or whether others can reasonably be expected to respect another’s conscientious claims. In order to find answers to these and related questions, a philosophical analysis is required, and will now be advanced.

Philosophical accounts of conscience fall roughly into three categories: as moral reasoning, as moral feelings, and as a combination of moral reasoning and moralfeelings (see Beauchamp & Childress 2001: 37–9; Rawls 1971: 205–11, 368–9; Mill 1962b: 281–4; Kant 1930: 129–35; Hume 1888: 458).

Conscience as moral reasoning

A reasonable or rationalistic account of conscience takes ‘extended consciousness’ encompassing the gathering of knowledge (Damasio 1999: 232), rational moral principles and reason as the source of one’s moral convictions. Conscientious judgments, by this view, are really critically reflective moral judgments concerning right and wrong (Garnett 1965; Broad 1940). Rational insight can be either religious or non-religious in nature, depending on what a person’s world views are. Either way, a rational conscience typically manifests itself as ‘a little voice inside one’s head saying what one should and should not do’ — also called ‘the “voice” of conscience’ (Benjamin 2004: 513). Or, to put this in moral terms, it tells us what our moral obligations and duties are. Statements of conscientious objection then are, by this view, merely statements of moral duty which individuals recognise and commit themselves to fulfil. Whether the duties or obligations identified impose overriding or absolute demands, or only prima-facie demands on the individual is, however, another matter entirely, and one that is considered shortly.

Conscience as moral feelings

There are two possible versions of a ‘moral feelings’ account of conscience — emotivist and intuitionist. Both consist of a tendency to spontaneously experience either emotions or intuitions ‘of a unique sort of approval of the doing of what is believed to be right and a similarly unique sort of disapproval of the doing of what is believed to be wrong’ (Garnett 1965: 81).

It is generally recognised that these feelings are quite different from the sorts of feelings we might have when, for example, looking at a beautiful painting (aesthetic approval) or an awful painting (aesthetic disapproval), or eating a favourite food (the feelings of mere liking) or smelling an awful smell (feelings of mere disliking), or witnessing an act of remarkable human achievement (feelings of admiration) or an act of extraordinary human failure (feelings of disdain). By contrast, in the case of wicked acts or the violation of duty, conscience may manifest itself in strong and distinguishable feelings of moral loathing, shame, remorse or even guilt (see Greenspan 1995), or, as Beauchamp and Childress (1989) suggest, the unpleasant feelings of ‘a loss of integrity, wholeness, peace, and harmony’ (p 387). To borrow from Fletcher (1966), conscience can manifest itself as ‘a sharp stone in the breast under the sternum, which turns and hurts when we have done wrong’ (p 54). In the case of virtuous acts, conscience may manifest itself as strong feelings of reassurance or moral goodness (Fletcher 1966: 54; Kant 1930: 130), or, as Beauchamp and Childress (1989) suggest, as feelings of integrity, wholeness, peace and harmony (p 387). Either way, moral feelings instruct individuals on what they ought and/or ought not to do. As with the rationalistic account, statements of conscience emerge as statements of obligation and duty.

Conscience as moral reason and moral feelings

The concept of conscience as a combination of reason and feelings basically involves an integrated response to ‘moral catalysts’ in the world. It does not rely on ‘blind emotive obedience’, as Kordig (1976) calls it, nor on an exclusive and blind devotion to reason. Rather, it relies on the mutually guiding and instructive forces of both moral sensibilities and moral reasoning. This account of conscience is, arguably, the most plausible of the three given, and is thus the one that underpins this discussion.

How conscience works

Now that we have briefly examined the essential nature of conscience, the next question is: How does conscience function as a moral authority?

It is generally recognised that conscience functions as a personal (internal) sanction and as a personal moral authority (Beauchamp & Childress 2001; Childress 1979). Claims of conscience typically identify individual people with their self-chosen or autonomously chosen standards and principles of conduct (Nowell-Smith 1954: 268). Further, they commit individual people to act in accordance with those principles. In other words, claims of conscience commit the individual person to act morally (Timms 1983: 41). Thus, when conscience is said to be ‘personal’ or ‘one’s own’, all that is being claimed is that a particular set of autonomously chosen moral standards has authority over a particular person — not, as is sometimes mistakenly thought, that the person has a unique and different set of moral standards from everybody else, and thus is a kind of ‘moral freak’.

Conscience can be appealed to both as a kind of ‘reviewer’ or ‘judge’ of past acts, and as an ‘authority on’ or as a ‘guide to’ future acts. Whether conscience is appealed to as judge or guide, however, it is important to understand that conscience is not morality itself, nor is it the ultimate standard (or even a standard) of morality. Rather, as Gonsalves explains (1985: 55), it is:

… only the intellect itself exercising a special function, the function of judging the rightness or wrongness, the moral value, of our own individual acts according to the set of moral values and principles the person holds with conviction.

Or, as Childress explains (1979: 319), it is merely ‘the mode of consciousness resulting from the application of standards’.

Gonsalves’ and Childress’ views make it plain that statements of conscience are not statements of a unique moral faculty or of unique moral standards. Rather, they are statements of a particular application of adopted moral standards. Conscientious objection, by this view, essentially translates into a case of moral disagreement in regard to which moral statements apply and what one’s moral duty is in a particular situation. If this is so, the case for respecting a conscientious objector’s claims becomes compelling — particularly in instances where there are no clear-cut moral grounds for settling a specific disagreement (as sometimes occurs in the cases of abortion, organ transplantation, assisting with the involuntary administration of electroconvulsive therapy [ECT] or psychotropic medication, administering blood to Jehovah’s Witness patients, and similar cases) (see also Wicclair 2000).

It should be noted here that, once it is accepted that claims of conscience translate into claims of duty, it is conceptually incorrect to speak of conscientious objection as a right (as some nursing position statements on the subject do). To assert this would be to assert that an individual has a ‘right to have a duty’, which is conceptually incorrect. It is more correct to speak of others being bound to respect another’s claim of conscience, just as they are bound to respect another’s claim of moral duty.

The problem remains, however, that consciences are fallible and can make mistakes (Seeskin 1978). As Nowell-Smith (1954: 247) points out, some of the worst crimes in human history have been committed by people acting on the firm convictions of conscience. Hitler, for example, believed he was fulfilling a supreme moral duty by purging the German race of its ‘Jewish disease’ (Kordig 1976). Others also point out that, in some instances, what appears to be a claim of conscience may be nothing more than a claim of prudence or self-interest or convenience. This invariably raises the question: Should I always obey my conscience? Further to this, claims of conscience can be insincere or counterfeit, raising the additional questions of: How can I distinguish between genuine and bogus claims of conscientious objection? Should I always respect another’s conscientious claims? It is to answering these questions that this discussion now turns.

B ogus and genuine claims of conscientious objection

For a conscientious objection to be genuine, it must satisfy at least five conditions.

1. It must have as its basis a distinctively moral motivation, as opposed to the motivations of mere self-interest, prudence, convenience or prejudice. By this is meant:

a. that the action has as its aim the maintenance of sound moral standards, and the achievement of a moral end (Garnett 1965);

b. that the person performing the act sincerely believes in the moral characteristics of the action in question, and sincerely desires to do what is right (Broad 1940: 75; Childress 1979: 334); and

c. that the desire to do what is right is sufficient to override considerations of fear, cowardice, self-interest and prejudice.

2. It must be performed on the basis of autonomous, informed and critically reflective choice. By this is meant:

a. that the action must be the individual’s ‘own’, so to speak — that is, it is not the product of coercion or manipulation; and

b. that that action has been carefully considered — that is, that the person has taken into account all the relevant factual as well as ethical information pertaining to the situation at hand, possible alternatives to the action being contemplated, and predicted moral outcomes of the action once it is taken (Broad 1940: 75).

3. It should be appealed to only as a last resort — that is, in defence of one’s moral beliefs. A claim of conscientious objection is a last resort when all other means of achieving a tolerable solution to a given moral problem have failed. Here conscientious objection is justified on grounds analogous to those justifying self-defence, which permit people to use reasonable force in order to preserve their integrity (in this case, their moral integrity) (Machan 1983: 503–5).

4. The conscientious objector must admit that others might have an equal and opposing claim of objection. For example, a nurse refusing on conscientious grounds to assist with an abortion procedure must be prepared to accept that the aborting surgeon may feel obliged as a matter of conscience to go ahead with the abortion. To quote from Broad: ‘What is sauce for the conscientious goose is sauce for the conscientious ganders who are his [sic] neighbours or his [sic] governors’ (Broad 1940: 78).

5. The situation in which it is being claimed must itself be of a nature which is morally uncertain; that is, there are no clear-cut moral grounds upon which the matter at hand can be readily and satisfactorily resolved, and competing views can be shown to be equally valid.

If we accept these criteria, the task of distinguishing bogus from genuine claims of conscientious objection becomes considerably easier. To illustrate this, consider four types of situations in which nurses commonly claim conscientious objection: the lawful but morally controversial directives of a superior; a conflict of personal values between a nurse and a patient; personal fear of contagion; and unsafe working conditions.

Conscientious objection to the lawful but morally controversial directives of a superior

Nurses as employees are compelled by the principle of employment law to obey the lawful and reasonable directives of an employer or superior. The problem is, however, that nurses might not always agree morally with the lawful directives they have been given, and thus may sometimes find themselves in the uncomfortable position of having to perform acts which violate their reasoned moral judgments (Johnstone 1998, 1994).

There are many examples of nurses having been caught in both personal and professional dilemmas on account of legal demands to obey the lawful though morally controversial directives of doctors and nurse superiors. Examples have typically involved situations in which nurses have been directed, against their will, to assist with morally controversial procedures such as abortion, euthanasia, ECT and organ transplantation. The difficulties nurses have encountered in such situations have been compounded by the fact that they have had little, if any, avenue for officially expressing their conscientious refusal without fear of losing their jobs or facing other threats.

Situations involving nurses’ conscientious refusal to follow lawful but morally questionable directives invariably pose the age-old question of whether an individual can, all things considered, be decently expected to follow morally controversial or morally bad, although legally valid, laws — or, in this case, lawful directives.

As can be readily demonstrated, the problem of legal–moral conflict is not new to philosophy. Questions of, for example, what is the proper relationship of morality to law, what is to count as a good legal system, or whether individuals ought to be compelled to obey immoral laws, have long been matters of philosophical controversy. Hart, an Oxford scholar and professor of jurisprudence, for example, argued half a century ago that existing law must not supplant morality ‘as a final test of conduct and so escape criticism’ (Hart 1958). He also argued that the demands of law must be submitted to the scrutiny and guidance of sound morality before they can be justly enforced (Hart 1961). Not surprisingly, these kinds of views have sparked intense debates in both philosophy and law. It is beyond the scope of this text to discuss Hart’s views and address the interesting questions concerning the philosophy of law that they raise. Nevertheless, it is assumed for argument’s sake here that any law which fails the test of sound moral scrutiny should be either adjusted or rejected; it is also assumed that to punish autonomous moral agents for refusing to obey lawful but morally questionable directives is morally unjust.

A number of other important considerations are worthy of attention here. First, there is the persuasive view that forcing nurses to act against their reasoned or conscientious judgments is to not only ignore or diminish their moral autonomy, but also to violate the principles of morality itself — not least those of autonomy and reflectivity (Muyskens 1982a: 61). Perhaps even more troubling is the possibility that violating nurses’ consciences would also unjustly violate their integrity as moral agents (see also Wicclair 2000; Childress 1979).

Second, it is generally recognised that if people are forced constantly to violate their conscience then their conscience will gradually weaken and lose its authority (Kant 1930). This in turn makes it easier for individuals to avoid fulfilling their perceived moral duties and/or acting in accordance with autonomously chosen moral standards. As a result, there is likely to be a general breakdown in compliance with moral rules and principles, and a general erosion of individual moral responsibility and accountability. It takes little to imagine what would happen to the moral fabric of the community at large if all its members were forced, say, by order of the state, constantly to violate their reasoned moral judgments or consciences. No less consideration is due to what may ultimately happen to the moral fabric of the nursing profession if its individual members are constantly forced to abandon their reasoned moral judgments and consciences in favour of preserving the prescriptions and proscriptions of law and convention.

Related to this is a third consideration — that moral duty ‘is mainly concerned with the avoidance of intolerable results’ (Urmson 1958: 72). If fulfilling one’s supposed duty does not avoid or prevent intolerable results, it seems reasonable to question whether in fact it was one’s duty in the first place. As with the case of supererogatory acts (that is, acts above the call of duty, such as those performed by saints and heroes), care must be taken to distinguish those deeds which can be reasonably expected of ‘ordinary’ persons (or ‘ordinary’ nurses) from those which it would merely be nice of ‘ordinary’ persons (nurses) to perform, but which could never be reasonably expected of them (Urmson 1958: 68). On this point, Urmson (1958: 71) argues: ‘… a line must be drawn between what we can expect and demand of others and what we can merely hope for and receive with gratitude when we get it’.

Fourth, those who coerce others to act against their conscience erroneously presume that coercion vitiates moral responsibility. This, however, is not so. Just as more sophisticated claims of duty cannot be escaped or deceived, neither can claims of conscience. It is a mistake to hold that, if a person is forced to perform an act to which they are conscientiously opposed, they are less morally culpable for that act, and that they will feel less morally guilty for having performed it. What users of force fail to understand is that an instance of moral violation still stands, regardless of whether it has been caused by an act of coercion or an act of free will.

Fifth, nurses are not automata or robots, but thinking, reasoning, feeling, responsible human beings. Legal law recognises this by the very fact that it can and does hold nurses independently accountable for their actions (Johnstone 1994). Given this, it is a mistake to hold that nurses have an unqualified duty to obey the directives of a superior.

Lastly, it is ultimately more desirable than not to have a health care system comprised of conscientious nurses. Nurses comprise 70% of the health care workforce. The prospect of 70% of health care providers being morally unconscientious is a bleak one. Since most of us cannot be saints, but can be conscientious, we need to preserve and cultivate conscientiousness (Nowell-Smith 1954: 259; Garnett 1965: 91). Only by doing this can we be assured of achieving and maintaining some sort of moral order in health care domains. As Seeskin (1978) argues, ‘… we have no guarantee that our deliberations will be perfect or our moral sensibilities adequate’ (p 299); it is for this reason, among others, that conscience and moral conscientiousness should be given a place among the moral virtues. We might be condemned as fanatics if we hold conscience to be infallible, but if we do not at least acknowledge its ultimateness in the scheme of moral reasoning, we might be guilty of moral negligence and moral irresponsibility (Seeskin 1978; Kordig 1976).

The consequences of such views have interesting implications for policy makers attempting to respond to the conscientious objection problem. These views seem to suggest that, even if nurses’ consciences are mistaken, on balance there are moral benefits to be gained by permitting their conscientious objections — not least, the benefits of fostering moral sensitivity and moral responsibility in the workplace. These views also suggest that, if nurses are not permitted conscientiously to object, then health care contexts, not to mention the community at large, will be morally worse off by virtue of being more at risk of suffering moral harms on account of receiving care that is not informed or guided by conscientious ethical beliefs and standards.

It might be objected here that permitting conscientious objection is not conducive to the efficient running of hospitals and other health services. There is, however, little support for this kind of claim. In the case of military service, for example, it has been found that objectors are rarely amenable to threats and usually make unsatisfactory soldiers if coerced, and that in fact there are generally not enough objectors to frustrate the community’s purpose (Benn & Peters 1959: 193). There is room to suggest that something similar is probably true of objectors in nursing. As many examples in the nursing literature have shown, nurses have preferred to resign and risk dismissal than perform acts which they find morally offensive. Further to this, those nurses who have been coerced have not wholly complied with given orders. (For example, I know of nurses who have resuscitated patients in cases of controversial DNR directives, and not resuscitated patients in the case of controversial CPR orders.) It is also unlikely that there are enough objecting nurses to obstruct the efficient running of the hospital system.

Where lawful directives entail a demand to perform morally controversial procedures, there is considerable scope for suggesting that a nurse has a firm moral basis upon which to conscientiously object. Issues such as abortion, organ transplants, electroconvulsive therapy, the enforced and involuntary treatment of psychiatric patients and euthanasia are all morally controversial, and, as yet, no morally clear-cut grounds exist for resolving them. Until these issues can be resolved satisfactorily, it would be morally indefensible and unjust to insist that nurses must, when directed, assist with abortion, organ transplantation, electroconvulsive therapy and euthanasia work — or any other work which is morally controversial. In other words, where a so-called ‘standard’ or ‘reasonable’ medical or nursing procedure is morally questionable, nurses cannot decently be forced to perform or participate in that procedure. Further, it is worth noting once again that what we have in a situation of conscientious objection is moral disagreement — something which, as discussed in Chapter 6, may not be resolvable. The most amenable solution seems to be to permit conscientious objection.

Conscientious objection and the problem of conflict in personal values

Between nurse and patient

The International Council of Nurses (ICN) (2006) Code for Nurses states that ‘the nurse’s primary professional responsibility is to people who require nursing care’. It further states that: ‘In providing care, the nurse promotes an environment in which the human rights, values, customs and spiritual beliefs of the individual, family and community are respected’ (ICN 2006). Sometimes, however, a nurse may find it genuinely difficult to respect a person’s (or a family’s or a community’s) values, customs and spiritual beliefs, and for this reason may decline to be involved in caring for such entities. Consider the following cases.

Case 1

A registered nurse working in a general medical ward was assigned a male patient who was known to be an orthodox Muslim. Upon learning of the man’s religion, the nurse refused to care for him, stating that she could not accept the attitudes of Muslim males towards women, and that if she cared for him she would be as good as condoning his (and his community’s) views.

Case 2

A registered nurse working in an infectious diseases unit was assigned a male patient in the end stages of AIDS. Upon learning that the patient was a homosexual and prior to his illness had been actively involved in the gay community, the nurse refused to accept the assignment. The nurse argued that as a Christian he could not condone homosexuality, and therefore it would be against his religious beliefs to care for the patient.

Case 3

A registered nurse working in a country hospital was asked to admit and care for a patient injured in a fight. When she recognised the patient as a member of a family who had been engaged in a feud with her own family for years, she declined to care for him. She stated as her reason that, were she to care for the man, she would be violating the loyalties she owed to her own family.

There is little doubt that all three registered nurses in the cases just given have sincere motivations behind their refusals to care for the patients in question. What is not so clear, however, is whether these motivations have a moral basis. For instance, their refusals to care for these patients seem to be based more on, for example, non-moral personal dislike, prejudice, fear, disdain or mere disapproval than on sincere moral motivation and the desire to achieve morally desirable ends. Second, it is not clear whether, by refusing to care for these patients, the nurses will preserve their moral integrity. In fact, it may be quite the reverse, since they have allowed personal interests to override the significant moral interests of their patients. Lastly, the professional demand to care for the patients in question is not itself morally controversial — at least, not in the same way that, say, the demand to care for and stabilise a ‘brain-dead’ patient for organ donation is (see Johnstone 1989: 302–18).

While it may be imprudent to compel the nurses in these cases to care for the patients assigned to them, it is not immediately apparent that it would be immoral to do so. It might be concluded then that their refusals can, at least from a moral perspective, be justly overridden. Nevertheless, there may still exist pragmatic grounds for permitting their refusals. If they cannot be relied upon to give adequate care, for example, it might be better to allow their refusal. If their prejudices and personal feelings are of such a nature as to seriously cloud their prudential judgments and indeed their ability to care and engage in an effective therapeutic relationship, it may be that they should not be allocated the patients in question. This, however, may be more a practical consideration rather than a moral one — although, granted, one which will probably have a significant moral dimension; namely, the patient’s wellbeing.

Conscientious objection — the fear of contagion and homophobia

The question of if, and when, and under what circumstances nurses may refuse to care for certain patients has become a particularly important and challenging one over the past two decades, largely because of the worldwide HIV/AIDS epidemic. Despite significant advancement in the care and treatment of people living with HIV/AIDS (estimated in 2006 to be around 39.5 million globally), the disease remains one of the most serious health problems in the world (United Nations [UN] & WHO 2006). Furthermore, although attitudes towards HIV/AIDS, and people living with HIV/AIDS are more positive and tolerant than they were two decades ago, discriminatory attitudes and practices by health workers towards patients with HIV/AIDS (especially those who are gay) are still a problem in some countries and contexts (Lohrmann et al 2000; Schuster et al 2005; Reis et al 2005; Röndahl et al 2003; Valois et al 2001; Walusimbi & Okonsky 2004). Research also shows that despite more progressive attitudes in society towards ‘diversity and difference’, gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgendered people are still regarded as ‘not yet equal’ (McNair & Thomacos 2005) and continue to experience significant prejudicial and discriminatory attitudes and behaviours on the part of nurses and doctors in health care contexts (Jones et al 2002; Mikhailovich et al 2001; Reis et al 2005; Schuster et al 2005). For example, when their sexual orientation is known by health care professionals, gay, lesbian and transgendered people in particular have reported such responses as ‘embarrassment by care providers, fear, ostracism, refusal to treat, demeaning jokes, avoidance of physical contact, rough physical handling, rejection of partners and friends, invasion of privacy, breaches of confidentiality, and feeling at risk of harm’ (Mikhailovich et al 2001: 182; see also McNair & Thomacos 2005; Reis et al 2005; Röndahl et al 2003; Schuster et al 2005).

Questions have been asked, both in Australia and overseas, about whether nurses can rightly refuse to care for HIV/AIDS patients (including infected newborns) (for an exhaustive discussion of this issue, see Crock 2001). During the early years of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, overseas research studies and opinion polls revealed that some nurses would rather abandon their practices and nursing careers than place themselves at risk by caring for HIV/AIDS patients (Huerta & Oddi 1992; Jemmott et al 1992; Melby et al 1992; Beard et al 1988; Lester & Beard 1988). In one US opinion poll, published in Nursing 88, it was revealed that 73% of nurses surveyed were concerned about their own safety, and 47% believed they had a right to refuse to care for HIV/AIDS patients; interestingly, an overwhelming majority (93%) stated that they had never refused to care for an HIV/AIDS patient, despite their fears (Brennan et al 1988). The poll also revealed that a staggering 80% of nurses surveyed stated that their own families were concerned about their (the nurses’) safety when caring for HIV/AIDS patients.

Other studies at the time also revealed that nurses caring for HIV/AIDS patients had been shunned by family, friends and neighbours, and even by other health care workers, who apparently feared association ‘with one who provides direct care’ (Huerta & Oddi 1992: 221; Nursing Times 1986a: 10). More recent research, however, has found that, even when concerned about contagion, most nurses and students of nursing have a positive attitude towards caring for patients with HIV/AIDS, are more empathic, less fearful and ‘are no longer worried about their relatives and friends after they come into contact with a person infected with AIDS’ (Lohrmann et al 2000: 700; Röndahl et al 2003; Walusimbi & Okonsky 2004). Even so, research is also showing that between 12% and 36% of health care workers would ‘feel uncomfortable’ working with a gay and/or HIV/AIDS positive patient and would refrain from providing care if given the opportunity to do so (Jones et al 2002; Reis et al 2005; Röndahl et al 2003; Schuster et al 2005).

Significantly, two of the most commonly cited reasons for refusing to care for HIV/AIDS patients are fear of contagion, and disapproval of patients’ lifestyles (especially those involving either homosexuality or intravenous drug use) (Crock 2001; Huerta & Oddi 1992: 223). A poignant example of how fear of contagion and disapproval of a patient’s lifestyle can affect the ability of nurses to care and, in turn, the patient’s overall wellbeing, is given below.

Case 4

A client was diagnosed as having AIDS upon his admission to hospital. During his inpatient stay, nurses often cracked open the door and called in to him to learn of his condition, but would not enter the room. The hospital staff would not bathe him, and he was not allowed to shower. Bloody linens were not removed from the room. His emergency bedside signal [call bell] was left unanswered for as long as eight hours. A pamphlet was left at his bedside that described homosexuality as a sinful practice (Staff of the National Health Law Program 1991: 260).

Although this is an American case, the prejudicial attitudes it demonstrates are not restricted to the national borders of the US. For example, when the AIDS epidemic started to evolve in Australia, a respected major hospital in Melbourne caused a public outcry when it imposed a ban on treating all people who had AIDS or who carried the HIV virus (Miller 1989b). The decision to impose the ban was made by the hospital’s medical advisory board, and was allegedly supported by both doctors and nurses working at the hospital, as well as by the Victorian branch of the Australian Medical Association (AMA) (Athersmith 1989a; Price 1989). As a point of interest, it was later revealed that nurses had not in fact been consulted about the decision to effect the ban (Curtis 1989). The hospital’s ban was the first case of its kind in Australia (Allender & Robinson 1989). Subsequently the Victorian Government took steps to outlaw hospital policies which effectively discriminated unjustly against HIV/AIDS patients.

It is doubtful whether HIV/AIDS (and/or other cases of infectious diseases — e.g. hepatitis B and C, drug-resistant tuberculosis, and SARS) presents a situation in which conscientious objection claims would be valid. Certainly, claims in these sorts of cases do not seem to satisfy all the five criteria of genuine conscientious objection listed earlier. For example, it is not clear that claims in these cases are based on a distinctive moral motivation aimed at maintaining sound moral standards or achieving a desired moral end. Nor is it clear that claims in these cases are based on informed and critically reflective choice (many may, in fact, be based on misinformed, fearful and arbitrary self-interested choice). It is also not clear that the claims of conscientious objection in these cases are necessary as a ‘last resort’ in ‘the defence of one’s moral integrity’. For one thing, it has yet to be shown how, if at all, caring for someone who is HIV positive threatens the moral integrity or standards of a caregiver (a point to be examined further shortly). Finally, it is far from clear that these cases involve a situation that is characteristically ‘morally uncertain’. (It has yet to be shown convincingly that it is unethical to care for someone who is seriously ill with an infectious disease.) While the objector may recognise that others’ conscientious claims are equally deserving in these cases, and thereby satisfy at least one of the five criteria listed, this is not enough to uphold a genuine claim of conscientious objection.

It should be noted, however, that, even though a claim of genuine conscientious objection might fail in cases of caring for people with potentially life-threatening infectious diseases, this does not necessarily mean that a given refusal to care by a nurse should not be permitted. One set of circumstances under which this might be so is where nurses are so distracted and so disturbed by their fear of contagion that they can no longer be relied upon to give safe, appropriate and therapeutically effective care. In such instances, it would obviously be better for the patient who has an infectious disease not to be cared for by such nurses. One reason for this is that the patient’s sense of wellbeing and self-worth — not to mention, his/her health outcomes — are not going to be maximised by nurses who are so overwhelmed by their own fear that they would neglect the patient (as happened in the case cited above). It needs to be noted, however, that nurses whose practice is ‘impaired’ by a personal fear of contagion have an obligation to seek remedial education and counselling to help address the problem of their ‘impaired practice’ (Johnstone 1998). In some jurisdictions, it might even result in a nurse’s deregistration. In 1990, for example, a nurse was deregistered by the United Kingdom Central Council (UKCC) for refusing to care for people who were ‘HIV, AIDS and hepatitis B positive’ (Young 1994: 103).

Another problem which needs to be addressed is that of homophobia (the ‘irrational fear of homosexuality’), which, as Huerta and Oddi (1992: 223) argue, can further compound the fear of caring for HIV/AIDS patients. Significantly, attitudinal studies conducted over the years have consistently found that some nurses feel uncomfortable with caring for male homosexuals and exhibit avoidance behaviour towards HIV/AIDS patients who belong to this group (Crock 2001; Lohrmann et al 2000; Huerta & Oddi 1992; Reis et al 2005). Nurses opposed to homosexuality also tend to believe that HIV/AIDS patients are ‘responsible’ for their disease, and, accordingly, these nurses ‘blame the victim’ (Crock 2001; Reis et al 2005; Viele et al 1984). Equally significant are research findings which show that nurses who are homophobic manifest ‘the greatest fear of HIV/AIDS and the least empathy for AIDS patients’ (Huerta & Oddi 1992: 224; Lohrmann et al 2000; Reis et al 2005).

While these studies are not conclusive, they nevertheless point to a need for nurses to examine their attitudes towards homosexuality and to explore ways in which prejudicial attitudes towards and fear of HIV/AIDS patients can be overcome (Crock 2001). One study has found, for example, that nurses can be helped to gain a more positive attitude towards and less fear of homosexuality by participating in sexuality workshops where opportunities can be provided to explore and share feelings about the issue, and to engage in other learning activities (Crock 2001; Valois et al 2001; Young 1988).

One group of people who may not be amenable to this kind of education, however, are those who are fundamentally opposed to homosexuality on religious grounds. I have, for instance, heard some nurses who hold conservative religious beliefs express the view that they ‘could not possibly care for a homosexual patient with HIV/AIDS, since to do so would be tantamount to condoning homosexuality, and thereby supporting a sinful practice’. (Similar arguments are used in the case of abortion; some nurses have expressed the view, for example, that caring for women who have had abortions is tantamount to condoning abortion.) The reasoning used here is, however, flawed. It is a fallacy to hold that caring for a particular class of patients is tantamount to condoning the lifestyles or life circumstances of those patients. If we were to accept this line of reasoning, we would be committed to accepting that, for example, caring for poor people is tantamount to condoning poverty, or that caring for unemployed people is tantamount to condoning unemployment, or that caring for homeless people is tantamount to condoning homelessness. We would, I think, reject the view that caring for these latter groups of people is tantamount to condoning their respective lifestyles, or to providing grounds upon which a morally defensible refusal to care for them could be based. Since the acts of caring for HIV/AIDS patients are demonstrably remote from the sexual acts to which some nurses are opposed on religious grounds, and since caring for patients who are homosexual does not entail performing acts proscribed by religious doctrine, it is not clear that a refusal to care for patients who are homosexual can be sustained (see also the collection of essays in Watt [2005] on the topic of conscience and the mediating Catholic principles of cooperation and complicity).

It might be objected here, however, that, unlike homosexuality, poverty, unemployment and homelessness are not ‘sins’ and therefore nurses opposed to sinful practices can care for people in these latter groups without compromising their religious beliefs and moral integrity. In fact, caring for these people might even be construed as ‘virtuous’. This, however, is not a satisfactory reply, since it fails to show why caring for these groups of people is not tantamount to condoning their lifestyles, which, significantly, can be shown to be injurious to these groups of people’s wellbeing and moral interests. Let us explore this further.

Why, for instance, is caring for a homosexual patient regarded as tantamount to condoning homosexuality, yet caring for an unemployed person is not regarded as tantamount to condoning unemployment? If we take out the descriptive statements referring to these groups whose respective lifestyles are in question, what we end up with is something like this: caring for members of group X is tantamount to condoning their lifestyles, but caring for members of group Y is not tantamount to condoning their lifestyles. No reasons are given why this is the case, however, demonstrating that the thinking being used here is at best arbitrary and at worst fallacious. Even if it is conceded that what makes a morally significant difference in this case is the ‘sinful’ nature of homosexuality, this will not help, since this seems to say that what makes caring for a particular group of people tantamount to condoning their lifestyles is the fact that what they do is ‘sinful’. If nurses holding conservative religious beliefs were to accept this, however, they would be committed logically to accepting that caring for a whole range of people would be tantamount to condoning their ‘sinful’ lifestyles, and thus that there exists a whole range of people for whom they should refuse to care. Nurses holding conservative religious beliefs would, for instance, be obliged to refuse to care for people who work on Sundays, bear false witness, steal, murder, covet their neighbours’ goods, fornicate, commit adultery, blaspheme, do not fear God, worship other gods, tell lies, take contraception, have attempted suicide, and have performed a whole range of other acts deemed sins in the Bible or other religious texts. Clearly, if nurses were to accept the view that caring for people who commit sins is tantamount to condoning the sins in question, they would probably have to give up nursing altogether, since many (if not most) people have committed at least some of the ‘sinful’ acts given above.

While the arguments presented here have had as their focus gay men, they could, of course, be applied equally to the cases of other groups of people whose lifestyles some nurses regard as being problematic or sinful — for example, intravenous drug users and prostitutes.

Conscientious objection and the problem of unsafe work conditions

A final type of situation to be considered here involves the common problem of nurses being expected to work in unsafe working conditions, most notably those caused by severe staff shortages. Typically, nurses might be ordered to work in an area with which they are unfamiliar and/or in which they are not educated to work, such as in an intensive care unit. They might also be expected to work at a staffing level which places patient safety and quality of care at risk. These two situations are inextricably linked. For example, if there was not a shortage of properly educated intensive care nurses, nurse administrators would not have to order an inexperienced nurse to go and ‘help out’ in the hospital’s intensive care unit. A nurse’s obligation to object to working under certain conditions may not only be morally imperative, however, but a legal requirement under ‘duty of care’ and the demand to exercise ‘due care’ provisions.

C onscientious objection and policy considerations

For a conscientious objection policy to be effective and reliable, it must carry at least two minimal requirements (see Childress 1979). First, conscientious objectors must demonstrate that their claims are sincere. A given proof need not be religious in nature, nor necessarily absolute. As we have seen throughout this book, it is not always inconsistent for nurses (or for anyone) to have a ‘moderate’ position on the moral permissibility of certain procedures, such as abortion and euthanasia/assisted suicide. Thus, it would not necessarily be inconsistent of nurses to, say, support abortion and to participate in most abortion procedures at their place of employment, yet nevertheless be opposed to a ‘particular case’ of abortion where the procedure in question fails to satisfy certain autonomously chosen moral standards. The same applies in the case of euthanasia/assisted suicide. Conscientious objection policies, then, must recognise and make provision for the moderate’s position, and accept that sometimes conscientious objectors might refuse to assist with a type of procedure they have previously assisted with, such as abortion.

A second minimal requirement is that employers must carry the burden of proof that no alternative is available when not permitting nurses to refuse on conscientious grounds to assist with a given procedure. It is difficult to accept that a claim of conscientious objection cannot be accommodated in cases where nurses have used rightful means in expressing a conscientious refusal — that is, superiors have been given advance notice of an intention to refuse, reasons for refusal have been made explicit, replacement or other attending personnel have not been unduly compromised, other interests of comparable moral worth have not been sacrificed, and patients have not been stranded. Where an administrator does not accept a nurse’s genuine conscientious objection claims, serious questions need to be asked about whether the administrator has sincerely tried to find viable alternatives which would make it possible for conscientiously objecting nurses to withdraw from situations they deem morally troubling or intolerable.

The key to settling the conscientious objection debate does not lie only in having enforceable mechanisms for protecting genuine conscientious objection claims, but also in having a demonstrable threshold beyond which nurses can base their claims. However, this threshold is one which can only be supplied by sound ethics education and agreed ethical standards within the profession.

Can superiors decently order nurses to perform tasks to which they are genuinely conscientiously opposed? The answer is ‘no’. To compel nurses to act against their conscience is to risk weakening their moral conscientiousness and hence their ability to be moral. To deny moral conscientiousness in health care domains is also to risk the moral interests of those requiring health care. Furthermore, superiors simply do not have the moral authority to dictate to another which moral standards ought and ought not to be appealed to in a given situation.

There is much to support the view that a health care system comprised of morally conscientious and sensitive nurses would be much better than one without such nurses. This seems to support the conclusion that genuine conscientious objection is not only morally permissible, but may even be, in the ultimate analysis, morally required.

The issue of conscientious objection in nursing is not as problematic as it used to be. Statements on conscientious objection and the circumstances in which it might be expressed are now reflected in most nursing codes of ethics and related position statements (see, e.g. ANA 2002; Royal College of Nursing, Australia [RCNA] 2000).

W histleblowing in health care

The ICN (2006) Code of Ethics makes plain that nurses have a stringent responsibility to ‘take appropriate action to safeguard individuals, families and communities when their health is endangered by a co-worker or any other person’. The codes of ethics ratified by other peak nursing organisations (e.g. the Australian Nursing Council, the New Zealand Nursing Council, the Nursing and Midwifery Council (UK), the American Nurses Association and the Canadian Nurses Association) have also taken a stance that obligates nurses to take appropriate action to safeguard individuals when placed at risk by the incompetent, unethical or illegal acts of others — including ‘the system’. Despite being a professional and ethical requirement, however, reporting acts that place others at risk may not be an easy thing to do and, as the nursing and legal literature amply demonstrates, may even be hazardous to the nurses who make such reports. Some notable examples of this are given below.

T heM oylan case ( Australia)

In 2002, the Australian Nursing Journal carried a feature article detailing the story of Kevin Moylan, a senior psychiatric nurse, who experienced a 6-year ‘journey into hell’ after he exposed the poor-quality practices at a psychiatric clinic in the Australian state of Tasmania (Armstrong 2002: 18–20). Moylan’s ordeal began after he reported a range of workplace safety issues to hospital management. His concerns included what he believed to be the legal and ethical abuse of patients, inadequate training of staff and the provision of incompetent services, and serious problems with workplace health and safety — including:

the employment of a temporary psychiatrist who was not registered, police reluctance to provide support to protect staff from dangerous patients, and the sexual harassment of patients.

(Armstrong 2002: 19)

The employment of the unregistered psychiatrist caused Moylan particular concern and provided the catalyst for him deciding that he ‘could not remain silent as patients were diagnosed, prescribed medication, and given electro-convulsive therapy by someone he considered a “fraud” ’ (Armstrong 2002: 19). The workplace safety issues provided a further catalyst for action after these ‘reached a critical level when Kevin [Moylan] himself was attacked by a patient’ (p 19). Significantly, when Moylan reported his concerns, rather than ‘being praised and rewarded for his advocacy role’ he was reportedly ‘isolated and intimidated into silence’ (p 19).

Concerned about the lack of response to the issues he had reported, Moylan decided to take the matter further and wrote to the then Tasmanian Minister for Health outlining his concerns. In a chain of circumstances remarkably similar to the Pugmire case (cited below) and the Pink case (referred to in Chapter 5), a copy of the letter was delivered to the Tasmanian Shadow Minister for Health who subsequently raised the matter in parliament, and named Moylan as the ‘whistleblower’. Unfortunately, this single act of naming removed Moylan’s anonymity and privacy and, in his own words, ‘changed his life forever’ (Armstrong 2002: 19). Over the next 6 years he lost his home, his farm, his livelihood and his health. Although the psychiatric clinic was eventually closed and Moylan received some compensation, his lost health, reputation and livelihood remain largely unaddressed. Now a campaigner against what he calls the ‘suppression of dissent in the system’, Moylan reflects:

I have been threatened, isolated, intimated and abused […] My actions were motivated by a desire to see justice done. I tried to protect my patients, but no-one protected me.

(quoted in Armstrong 2002: 19)

As a consequence of not being protected, at the time the Australian Nursing Journal report was published, Moylan was suffering from a post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and unable to work. He was reported as having ‘nothing left but his car and his dog’ (Armstrong 2002: 19).

T heP ugmire case (N ew Zealand)

In 1993, Neil Pugmire, a registered psychiatric nurse, wrote in confidence to the then Minister of Health outlining concerns he had about the Mental Health (Compulsory Assessment and Treatment) Act 1992 (New Zealand) and its failure to provide for the compulsory detainment of patients whom responsible mental health professionals strongly believed were ‘very dangerous’ (Liddell 1994: 14). To support his concerns, Pugmire used as an example a named patient whom mental health professionals thought was ‘highly likely’ to commit very serious sexual crimes against young boys. This concern was based on admissions by the named patient (who, 7 years previously, had attempted to rape and strangle two boys) that he had continual feelings of ‘wanting to commit sexual acts with little boys’ (p 15). The Minister, however, reputedly took the position that ‘mental health legislation should not be used to justify the detention of difficult or dangerous individuals’ (p 14). Dissatisfied with this response, Pugmire sent a copy of his letter to a member of the opposition, Mr Goff (p 14). In a chain of events, similar to those that occurred in the Moylan case (referred to above), Mr Goff subsequently released the letter publicly, but with the patient’s name deleted. However, the patient’s name was eventually revealed by other sources thus breaching his confidentiality. Consequently, Pugmire was suspended by his employer for ‘serious misconduct’ involving the ‘unauthorised disclosure of confidential patient information’ (p 16).

T heB ardenilla case (US)

In 1988, in what has been described as ‘one of the most influential whistleblowing incidents ever to be initiated by a nurse during [the 20th] century’, Sandra Bardenilla, a registered nurse, was awarded damages for wrongful dismissal (involuntary resignation) from her place of employment ( American Journal of Nursing 1988: 1576; Fry 1989b: 56; Anderson 1990: 5–6). Bardenilla lost her employment as a result of reporting her concerns about two physicians whom she believed had directed ‘unethical and potentially illegal nursing care to a comatose patient who later died’ (Fry 1989b: 56).

It is reported that during the course of attempting to have the matter addressed, Bardenilla was ‘sharply criticised and accused of overstepping her role as a nurse’ (Fry 1989b: 56). Bardenilla was instructed by her director of nursing to ‘be quiet and to apologise’ to the physicians concerned (Fry 1989b: 56). She was also advised to ‘adopt a more realistic attitude about the hospital system, and she was warned against taking her concerns outside the hospital’ (Veatch & Fry 1987: 176). Bardenilla did not accept these directives, however, and resigned from her position instead. Following her resignation, she formally reported the two physicians to the local county health department who initiated an investigation into the matter (Veatch & Fry 1987: 176; American Journal of Nursing 1988: 1576). Following the investigation into the death of the patient, the two attending physicians were charged with murder. Although the physicians were both subsequently acquitted of the charges against them, ‘the case had a strong influence on subsequent termination-of-treatment decisions across the US’ (Fry 1989b: 56). The consequences to Bardenilla, however, were extremely burdensome at both a personal and professional level. As Sara Fry notes (1989b: 56), although Bardenilla eventually received financial compensation for her employment losses, she nevertheless:

received a great deal of recrimination as a result of her actions. While she received the support of many individual nurses, she did not receive formal professional support or find re-employment an easy matter. She suffered personal harm and the matter dragged through the courts for a long time.

T heM acArthur health service case (A ustralia)

In 2002, four nurses met with the then New South Wales (NSW) Minister for Health to draw to his attention certain management and clinical practices that they believed were placing patients’ safety at risk — and had already resulted in patient deaths — at two hospitals that were part of the MacArthur Health Service (MHS) in NSW. These nurses, together with three other nurses who later came forward in the formal investigation that was to follow, had between 13 and 30 years’ nursing experience, and included clinical nurse specialists and nurse unit managers. As one report put it:

Their professional experience enabled them to identify deficiencies in patient care and to alert the management of the hospital to problems.

(Health Care Complaints Commission 2003: 2)

The Health Minister referred the matter to the Director-General of the NSW Department of Health; the Director-General, in turn, made a formal complaint to the NSW Health Care Complaints Commission who then formally investigated the matter. The Commission’s investigation included an analysis of 47 specific clinical incidents that occurred between June 1999 and February 2003, in the emergency departments, the intensive care unit (of one hospital), the operating suite (of one hospital) and on the medical wards of both of the hospitals involved. Significantly, ‘the evidence obtained about the incidents strongly supported the allegations by the nurse informants about the standard of care’ (Health Care Complaints Commission 2003: 4). Some examples of the clinical incidents verified are:

▪ no surgical review of a patient with very poor blood supply to her foot — an urgent surgical problem (an ischaemic foot), for more than two days;

▪ unacceptable delay in triage of a severely ill newborn baby;

▪ a patient with severe chest pain was discharged from in [sic] an emergency department when a bed with a cardiac monitor could not be found — she died a few hours later;

▪ a critically ill cardiac patient who was in shock was left untreated in [an] emergency department for many hours;

▪ failure to diagnose a patient with serious post-birth infection (puerperal sepsis) in the emergency department;

▪ a delay of over 12 hours in the transfer of a critically ill woman;

▪ post operative intra-abdominal infection not diagnosed for four days;

▪ an agitated psychotic patient who waited unsupervised in an emergency department for five hours and subsequently absconded.

(Health Care Complaints Commission 2003: 4)

The nurses’ ‘whistleblowing’ actions in this case cost them dearly. For instance, in the days, weeks and months following their action, they were vilified and isolated by some of their colleagues (‘because of the criticism of the health service brought about by the investigation’ that followed after their allegations were made public). All four of the nurses were also disciplined by the health service — one of whom was suspended. Of these nurses, two were disciplined after they had apparently ‘intervened’ on the behalf of a child patient in the operating theatres. Following an investigation into this particular matter, the health service recommended that the nurses be disciplined ‘over the way they had addressed a medical officer’ (Health Care Complaints Commission 2003: 5).

The matter did not end with the Health Care Complaints Commission’s investigation, however. In what arguably stands as one of the most significant nurse whistleblowing cases to occur in Australia, following the release of the Commission’s report, the current NSW Health Minister sacked the head of the NSW Health Care Complaints Commission and announced a new inquiry — to be headed by an eminent barrister at law (Johnstone 2004a). This sacking came amid claims that the Commission’s report did not go far enough in holding people accountable (Johnstone 2004a). In addition to the sacking of the Commission’s head, two doctors were suspended, nine other doctors were referred to the NSW Medical Board for investigation and possible disciplinary action, and disciplinary action was initiated against four senior administrative staff at the health service (Saunders 2003a, 2003b). As well, an investigation was commenced into two further allegations, notably, that the former Minister for Health threatened and bullied two of the nurses who first went to him with their allegations, and that crucial documents pertinent to the allegations had been shredded at the two hospitals involved (Saunders 2003a, 2003b).

Despite having their concerns validated and receiving an apology from the Minister for Health as well as the MacArthur Health Service (a subsequent inquiry into the disciplinary action taken by the Service concluded that there was no evidence linking the disciplinary action to the whistleblowing — the action was ostensibly taken on other grounds) (see Hindle et al 2006: 49), the nurses’ careers and lives were changed forever. Meanwhile questions raised in the news media about the nurses’ ‘real’ motivations in this case remain unanswered and continue to cast doubt on the nurses’ integrity in this case.

T heB undaberg Base Hospital case (A ustralia)

In 2003, Dr Jayant Patel, a general surgeon based in the US, was appointed as a surgical medical officer (and subsequently promoted to Director of Surgery) at Bundaberg Base Hospital in the Australian state of Queensland. Over a 2-year period between 2003 and 2005, Dr Patel operated on approximately 1000 patients, of whom 88 died and 14 suffered serious complications (Van Der Weyden 2005). During this period, Toni Hoffman, the nurse in charge of the intensive care unit at the hospital, had serious misgivings about Dr Patel’s practice and repeatedly raised her concerns about patient safety and Patel’s treatment of patients with the relevant hospital officials and other authorities — none of whom took her concerns seriously (see also Thomas 2007). Hoffman is reported to have spoken to ‘the police, the Queensland coroner and up to 12 other officials about patient deaths before she went to a state lawmaker’ and authorities started to take her concerns seriously with an official inquiry into the matter being called ( Reuter’s Health 2005).

The events that followed the inquires led to resignations of the Queensland Minister for Health and the Director-General of Queensland Health, the General Manager and Director of Medical Services of the Bundaberg Base Hospital, and the suspension of the Director of Nursing (Dunbar et al 2007). A clinical review, meanwhile, found that Dr Patel had ‘directly contributed’ to the deaths of eight patients and ‘may have exhibited an unacceptable level of care in another eight patients who died’ (Van Der Weyden 2005: 284). The review also reportedly found that although ‘in the comfortable majority of cases examined, Dr Patel’s outcomes were acceptable … [he] lacked many of the attributes of a competent surgeon’ (Van Der Weyden 2005: 284). Despite these findings, Dr Patel was able to leave Australia before investigations into his conduct were completed and any measures taken to hold him accountable for his actions (Dunbar et al 2007).

The ramifications for Toni Hoffman of being a ‘whistleblower’ have been huge (Jones & Hoffman 2005). In a published conversation with the editor of the Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing about the case, Hoffman describes her ‘aloneness’, fear and sense of threat she felt she was under :

… I went alone to see the Member of Parliament for my area. I was very fearful; I did not know what he was going to do […] I have been threatened by telephone and out in the community. I have been vilified on the stand and had to ‘cop it’. This situation was far worse than I had ever imagined.

(Hoffman, in Jones & Hoffman 2005: 5)

It has also been revealed from various sources (including the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s Australian Story ‘At Death’s Door’ (ABC 2005), that she was warned by senior medical officers and executives at the hospital that she could face disciplinary action and could even lose her job and serve jail time if she went public with her concerns (Australian Private Hospitals Association 2007). Despite being totally vindicated for her actions and her advocacy for patient safety at Bundaberg (in recognition of what she did, she was made Australian of the Year Local Hero 2006), in her own words, the entire affair has had ‘a huge personal toll’ (Australian Private Hospitals Association 2007).

The above cases and other examples demonstrating the consequences to nurses who ‘blow the whistle’ are just some among many that show that deciding whether to report unsafe practices or to remain silent is not a straightforward matter (see also the UK cases of Graham Pink and Dr Nigel Cox given respectively in Chapters 5 and 10 of this book). Here questions arise of: Why is whistleblowing problematic? And what, if anything, can be done to improve the status quo? It is to answering these questions that the remainder of this discussion now turns. Before proceeding, however, some clarification is required on what the term ‘whistleblowing’ refers to.

T he notion of whistleblowing/whistleblowers

The term ‘whistleblowing’ is a colloquial term that is used to refer to:

The voluntary release of non-public information, as a moral protest, by a member or former member of an organization outside the normal channels of communication to an appropriate audience about illegal and/or immoral conduct in the organization or conduct in the organization that is opposed in some significant way to the public interest.

(Boatright 1993: 133)

Citing Elliston et al (1985), Vinten (1994: 256–7) argues that in order for an act to count as whistleblowing, the following conditions must be met:

▪ an individual performs an action or series of actions intended to make information public

▪ the information is made a matter of public record

▪ the information is about possible or actual, non-trivial wrongdoing in an organisation

▪ the individual who performs the action is a member or former member of the organisation.

Vinten (1994) further clarifies that whistleblowing disclosures lack authorisation, and can apply to both internal and external whistleblowing (see also Coyne 2003; Dougherty & Weber 2004; McDonald 2002; Rosen 1999). Others contend that whistleblowing reports are also usually made to a person in a position of authority (i.e. who has the power to stop the wrong), or to some other entity who, if not having the direct power to stop the wrong, nevertheless is perceived to have the capacity to exert pressure on those who do have the power to stop the wrong — for example, the media (Rosen 1999).

A key reason people resort to whistleblowing is to cause other people to pay attention and to take action immediately. Like the siren of an ambulance or a police car, or the fire alarm in a building, the sound of the ‘whistleblower’ seeks to alert people immediately to the fact ‘that something is either happening or is about to happen [and] there is a need to pay attention to the alarm that has been sounded’ (Erlen 1999: 67). Erlen (p 67) explains:

Just as the ring of the alarm clock arouses people from sleep, so, too, does an act of whistleblowing. While other sounds and their respective messages do not always signal danger or caution, whistleblowing within the context of a health care situation says that something is seriously wrong.

D eciding to ‘go public’

A key question facing members of the nursing profession is: Are there situations in which nurses should ‘go public’? The short answer to this is yes, no, maybe — depending on the circumstances at hand and whether there genuinely are no other avenues for having the situation addressed.

There is no question that if and when encountering a situation in which the care of individuals is being — or is at risk of being — endangered by a co-worker or any other person, nurses have a stringent responsibility to take appropriate action. The issue here is not whether nurses should take action, but rather what kind of action they should take.

In situations involving an exceptionally serious failing that, in turn, is placing the public or the public interest at serious risk, and no other means exist for having the situation remedied, it is understandable that a nurse (or nurses) might consider whistleblowing as an option (Erlen 1999). Even so, every effort should be made to first try and correct the situation internally before ‘going public’ (Rosen 1999: 41). There are two reasons for this: first, as we have seen, there are significant risks associated with whistleblowing; second, given developments in clinical governance and clinical risk management in recent years, new and more effective processes are now being put in place in health care organisations across the globe that are enabling staff to raise issues of safety and quality within their organisations without having to resort to the extreme measure of whistleblowing (Johnstone 2004a). Let us consider these claims further.

R isks of whistleblowing