CHAPTER 89 Military Psychiatry

OVERVIEW

Negative effects of combat exposure can persist for decades, as Prigerson and colleagues1 demonstrated in a study of 2,583 men ages 18 to 54 who received standardized psychiatric interviews in the National Comorbidity Survey. They found that combat exposure resulted in high prevalence rates of psychiatric diagnoses and psychosocial problems: 28% had posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD); 21% engaged in spousal or partner abuse; 12% experienced job loss; 9% were currently unemployed; 8% had 12-month substance abuse problems within 1 year; 8% underwent divorce or separation; and 7% sustained major depressive disorder (MDD).

PSYCHIATRIC SYNDROMES IN THE IMMEDIATE AFTERMATH OF MILITARY OPERATIONS AND TERRORIST EVENTS

Delirium

In combat or following terrorism that leads to major illness or injuries, volume depletion and metabolic derangements can cause delirium (manifest by clouded consciousness, agitation or diminished responsiveness, and disorientation) (Table 89-1). Pharmacological agents (such as neuroleptics and benzodiazepines) used to manage agitation can further complicate medical assessment and management, especially surrounding combat-related injuries. Symptomatic management of behavioral problems with sedating agents should be initially reserved to protect the life or safety of the patient and other patients or staff. Resolution of the etiology of the delirium should be the primary goal; resolution requires attention to metabolic sequelae of the injury. Common causes of delirium in combat or in disaster settings include hypovolemia, hypoxemia, central nervous system mass effects, infection, and adverse effects of resuscitative medications.

Table 89-1 Common Psychiatric Syndromes and Phenomena in the Immediate Aftermath of Military Operations and Terrorist Events

Depression

Depressed mood or resignation in the aftermath of combat or a terrorist event may be difficult to distinguish from the malaise and lassitude common among the prodromes to exposure to many chemical and bioterrorism agents. When depressed mood and associated depressive symptoms disrupt social and occupational function, MDD is diagnosed.

Acute Stress Disorder and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Symptoms of acute stress disorder (ASD) and PTSD include reexperiencing phenomena (such as dreams and flashbacks), hyperarousal, avoidance of events or situations that resemble—even symbolically—the original trauma, and dissociative phenomena (such as derealization or numbing).2 When symptoms persist for more than 1 month, PTSD is diagnosed. ASD and PTSD do not occur in a vacuum. When one of these disorders exists, it is highly probable that another psychiatric condition (see Table 89-1) exists as well, especially MDD, panic attacks, panic disorder, substance use disorders, and generalized anxiety disorder. Having a physical injury increases the risk of both ASD and PTSD.3

Unexplained Physical Symptoms and Conversion Symptoms

Use of biological or chemical agents presents a challenging differential diagnosis and contagion problem. During World War I “gas hysteria” was common and threatened the integrity of entire military units. Psychological casualties in chemical and biological threat scenarios may outnumber and prove more costly in terms of personnel losses than physical casualties. Acute symptoms of gas hysteria may mimic symptoms (e.g., dyspnea, coughing, aphonia, and burning of the skin) of poison gas exposure. Patients may have air hunger and other symptoms that are consistent with anxiety and panic. Factors that predispose to psychological contagion include rates of wounding/exposure in the unit, lack of sleep, and lack of prior experience with these phenomena/attacks.4 Therefore, it is important to know what substances a patient has not been exposed to. Following a faked chemical or biological agent threat, there may be a large number of individuals who fear that they have been exposed and will have realistic symptoms based on their knowledge of the alleged agent and the vital sign abnormalities produced by anxiety/fear.

Battle Fatigue and Operational Stress

Beyond traditional psychiatric disorders, “battle fatigue” and “operational stress” are also important practical concepts in military psychiatry. Symptoms such as gastrointestinal distress, tremulousness, and transient perceptual disturbances (including depersonalization and derealization) occur in response to the traumatic exposure, to sleep deprivation, to loss of social supports, or to any combination of these stressful factors associated with military operations. Minor injury, parasitic infection, starvation, heat exhaustion, or cold injury may also deplete adaptive homeostatic mechanisms and contribute to operational stress symptoms.

EFFECTS OF RESUSCITATIVE MEDICATIONS

Resuscitative medications are crucial to effective management of acutely injured patients. Unfortunately, many of them can cause neuropsychiatric or autonomic symptoms (Table 89-2). It is important to find out which medications an injured patient has received, in what amounts, and over what time period. Agents such as intravenous (IV) fluids (e.g., water), epinephrine, lidocaine, atropine, sedatives, nitroglycerin, and morphine are commonly used and have significant psychiatric or autonomic effects. These effects can resemble symptoms of primary psychiatric disorders. For example, atropine causes significant anxiety and anticholinergic effects. Epinephrine causes elevations in blood pressure and heart rate, and stimulates patients to feel anxious or panicky. Morphine causes sedation and impairs orientation and responsiveness.

Table 89-2 Resuscitative Medications That Can Cause or Mimic Psychiatric or Neurological Syndromes

| Medications | Signs/Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Intravenous fluids (water) | Delirium/hyponatremia |

| Epinephrine | Blood pressure/heart rate elevations, anxiety |

| Lidocaine | Delirium, psychosis |

| Atropine | Delirium, anticholinergic effects, anxiety |

| Sedatives | Depressed consciousness/responsiveness |

| Nitroglycerin | Dizziness |

| Morphine | Sedation, delirium |

LEVELS OF CLINICAL PREVENTION AND INTERVENTION: SYMPTOMS VERSUS FUNCTION

Distress and highly emotional responses are nearly universal during combat. Therefore, initial psychiatric interventions must focus on the mobilization of effective function to allow the military mission to continue. Military psychiatric theory and doctrine have long operated on the principle that transient and near-universal symptoms (that represent normal responses) can become “medicalized” if physicians reinforce a view that these symptoms constitute a disease. Levels of clinical intervention are conceptualized and deployed according to this doctrine (Table 89-3).

Table 89-3 Levels of Psychiatric Intervention and Care following Combat or Terrorist Attack

| Intervention Level | Indication |

|---|---|

| Support during combat | Consultations with leaders to mobilize effective function, to allow the military mission to continue |

| Combat stress control teams | Manage distress and acute psychiatric syndromes (as closely as possible to the area of operations) to maximize chances of a rapid return to effective function; use a mobile “holding environment” |

| Traditional psychiatric clinics | In the theater of operations, at aeromedical evacuation staging areas, or at fixed military bases in the United States, traditional psychiatric assessment and treatment can be provided at different times following one’s departure from the theater of operations |

| Inpatient psychiatric clinics | For patients with severe psychiatric illness or those with safety issues |

| Consultation-liaison services | For physically injured patients who need psychiatric care in military hospitals and rehabilitation units |

| Veterans Administration and community medical facilities | For veterans returned to their communities with ongoing mental health needs |

Other service members complete their combat tours of duty, but then develop mental health concerns or impaired function after returning home. In 2004 an anonymous survey5 administered to United States servicemen either before, or 3 to 4 months after, deployment to Iraq (n = 2,530) or Afghanistan (n = 3,671) suggested that a significantly higher percentage met screening criteria for major depression, generalized anxiety, or PTSD (15.6% to 17.1%) after deployment to Iraq than they did after duty in Afghanistan (11.2%) or before deployment (9.3%). Over one-third of Iraq war veterans accessed mental health services in the year after returning home, and 12% were diagnosed with a mental disorder. These data highlight the importance of making mental health resources available to meet the needs of returning veterans, and not just to those recently exposed to combat or to terrorist attack.

FACTORS RELATED TO DEVELOPMENT OF PSYCHIATRIC DISORDERS AMONG SERVICE MEMBERS EXPOSED TO COMBAT OR TERRORIST ATTACK

Neurobiological Factors

The emotional and behavioral responses to trauma are rooted in a combination of social, autonomic, and voluntary mechanisms that are increasingly being understood at the molecular level (Table 89-4). In the immediate phase of the stress response, the release of corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), the secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), the surge of peripheral catecholamines, and the activation of cortical brain areas related to perception of threat accompany extremes of environmental stress. Changes in behavior and cognition correlate with these noradrenergic phenomena. The immediate impact of acute stress under most conditions is improved performance. However, as the capacity to act becomes inadequate to meet continued demands, the risk for cognitive dysfunction increases and behavior often becomes too narrowly focused. An aroused, but focused, state may result in a difficulty with shifting sets or changing plans of action (e.g., adapting). If extreme distress disrupts cognition and creates chaotic thinking, the overfocused fight-or-flight response may result in immobility.

Table 89-4 Factors Related to Development of Psychiatric Disorders among Service Members Exposed to Combat or Terrorist Attack

| Factor Type | Observations |

|---|---|

| Neurobiological factors | Corticotropin-releasing factor release |

| Adrenocorticotropin hormone release | |

| Peripheral catecholamine surge | |

| Amygdala activation | |

| Predisposing factors | Women are at higher risk for postcombat PTSD, anxiety disorder, depression |

| Men are at higher risk for substance use disorder, antisocial/violent behaviors | |

| Preexposure level of function | |

| Past traumatic exposure history and experience | |

| Protective factors | Unit cohesion |

| Unit loyalty and interpersonal trust | |

| Strong leadership | |

| Precipitating factors | Intensity and duration of combat exposure |

| Physical injury | |

| Witnessing death or atrocities | |

| Sexual assault | |

| Mitigating and perpetuating factors | Safety and security of recovery environment |

| Degree of secondary traumatization | |

| Rotation schedules | |

| Recognition and rewards | |

| Quality of medical and psychological assistance provided | |

| Psychosocial situation at home |

PTSD, Posttraumatic stress disorder.

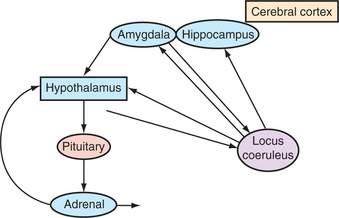

The immediate alarm response is followed by a cascade of neuronal and intracellular events that lead to elevated levels of CRF, increased synthesis of cortisol-related receptors, and activation of protein synthesis in subcortical nuclei of the amygdala that are responsible for the encoding of emotionally laden memories and the development of conditioned responses or habits. Hypersecretion of epinephrine also seems to exaggerate and consolidate fear-related memories. These changes may provide the molecular foundation for intrusive thoughts, exaggerated startle responses, and a general state of hyperarousal that is observed as clinically significant pathology in PTSD and ASD6 (Figure 89-1).

Predisposing Factors

The level of functional impairment in the aftermath of combat or disaster is related to pretrauma function. Individuals who function marginally in social, or in their occupational, roles before combat or exposure to disaster are at increased risk of poor function after exposure to trauma. The extent to which past traumatic experiences may produce future resilience or vulnerability is unclear. If a person has successfully negotiated combat or disaster situations in the past, he or she may be less traumatized by subsequent exposures. On the other hand, if past traumatic experiences have produced PTSD or other psychiatric syndromes, further traumatic exposures may trigger exacerbations, or emergence, of new psychiatric disorders.

MANAGEMENT AND CARE DELIVERY

Therapeutic Interventions in Psychiatric Casualties

Antipsychotics and anxiolytics used in the acute management of delirium or psychosis may alter levels of antimicrobial agents and acetylcholinesterase inhibitors used in the treatment of biological or chemical terrorist attack victims. Dose-related side effects (e.g., akathisia and somnolence) of antipsychotic agents may be mistaken for primary symptoms of an infectious, a post–physical-trauma, or a chemically mediated encephalopathy. Therefore, a conservative approach that minimizes the initial use of psychotropics is warranted. Short-acting hypnotics may be used to restore normal sleep patterns in cases where insomnia appears as the primary cause of dysfunction.

Psychosocial interventions have an important role in secondary prevention in military trauma victims. Group debriefing techniques and critical incident stress debriefings have been used, although there is no convincing evidence that such debriefings reduce the incidence of PTSD; in fact, several studies suggest that these interventions may be harmful.7 On the other hand, ongoing and frank discussions among squad members after a critical incident (such as an ambush or a raid) can open lines of communication to coordinate and evaluate the efficacy of actions, while fostering cohesion and group understanding of an event. These discussions, called “After Action Reports,” “Lessons Learned,” or “Historical Debriefings,” may serve to sustain the performance of persons critical to the management of the mission, may decrease individual isolation, and may help identify team members who may require further psychiatric or other mental health attention.

ETHICAL CHALLENGES

Physicians, including psychiatrists, may be asked to provide consultative assistance to persons who gather intelligence on detainees. This has created an ethical dilemma. Position statements and reports of a number of professional organizations (including the American Medical Association)8 and the Department of Defense indicate that health care professionals who provide treatment to detainees must not assist in interrogations, and that torture, or otherwise inhumane or coercive interrogations, is not acceptable. However, disparities in these reports suggest that the degree to which health professionals not engaged in the treatment of detainees may apply their knowledge and skill sets to assist interrogators in safe, ethical, and humane interrogations remains unsettled.

CONCLUSION

Health care professionals should consider behavioral and psychiatric issues in the context of an overall medical-surgical differential diagnosis in the aftermath of combat or a ter-rorist event, including possible chemical and biological attacks. When psychiatric signs and symptoms confuse or co-exist with medical-surgical injuries and conditions, psychiatric consultation early in the triage and management process can ensure more timely, accurate, efficacious, and cost-effective management of combat casualties or victims of terrorism.

1 Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Rosenheck RA. Population attributable fractions of psychiatric disorders and behavioral outcomes associated with combat exposures among US men. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(1):59-63.

2 American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2000.

3 Rundell JR, Ursano RJ. Psychiatric responses to war trauma. In: Ursano RJ, Norwood AE, editors. Emotional aftermath of the Persian Gulf War. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, 1996.

4 Jones FD. War psychiatry. In: Jones FD, editor. Textbook of military medicine. Part I, warfare, weaponry, and the casualty. Washington, DC: Office of the Surgeon General at TMM Publications, 1995.

5 Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, et al. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(1):13-22.

6 Southwick SM, Bremner JD, Rasmusson A, et al. Role of norepinephrine in the pathophysiology and treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:1192-1204.

7 Bryant RA. Psychosocial approaches to acute stress reactions. CNS Spectrums. 1998;10(2):116-122.

8 American Medical Association: Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs Report 10-A-06—physician participation in interrogation. June 2006.