Implantable Venous Access Device: Access, Deaccess, and Care

Implantable Venous Access Device: Access, Deaccess, and Care

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• Understanding of the implantable venous access device, including the septum and outer borders, is needed.

• Knowledge of the anatomy of the venous system is necessary.

• Understanding is needed of the principles of medication delivery. Intermittent use necessitates flushing with normal saline solution (NS) after each use and instillation of heparin as prescribed.

• Understanding of the principles of aseptic and sterile technique is necessary.

• The properties of chemotherapeutic or cytotoxic agents and preferred delivery techniques should be understood.

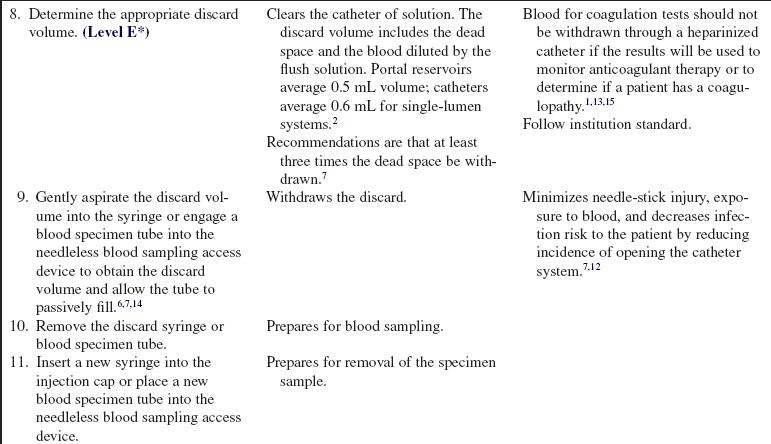

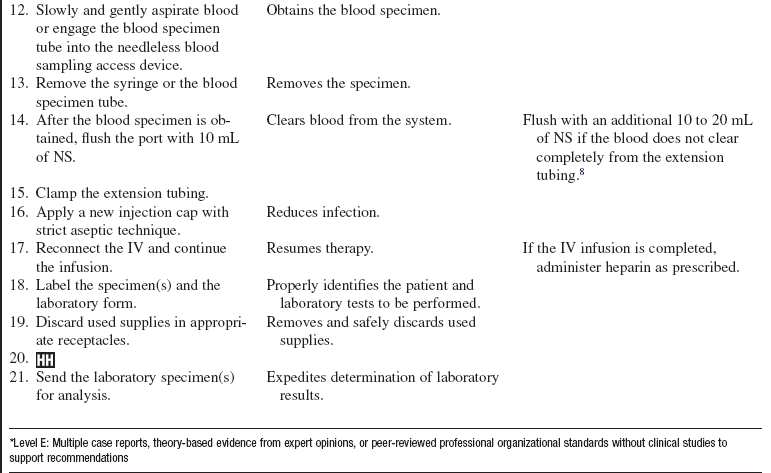

• Understanding of the consequences of infiltration of vesicant substances is needed.

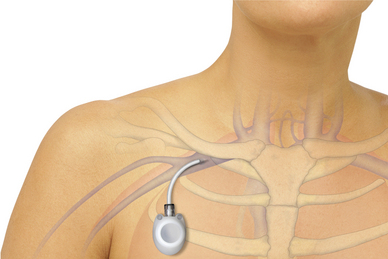

• Implanted venous access devices are surgically placed, totally implanted in a cutaneous pocket (usually in the chest wall), and designed to provide venous access for intermittent or continuous infusions, maintaining a patient’s intact body image when not accessed.

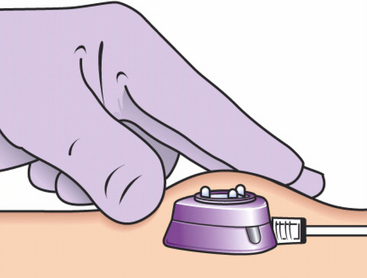

• Implanted devices consist of a slim tube or catheter connected to a reservoir, which is covered by a disc 2 to 3 cm in width (Figs. 83-1 and 83-2). The disc is made of silicone and is referred to as the septum. Provided a noncoring needle is used to access the septum, the septum is capable of resealing when deaccessed. The internal catheter is connected to the patient’s venous system and may consist of either silicone or polyurethane.5,15

Figure 83-1 Port placement. (Courtesy of Bard Corporation).

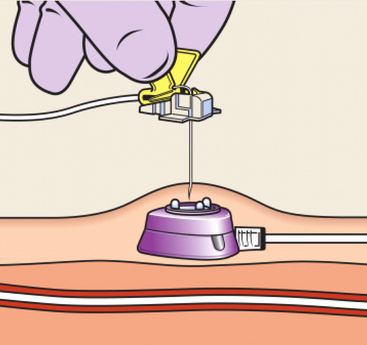

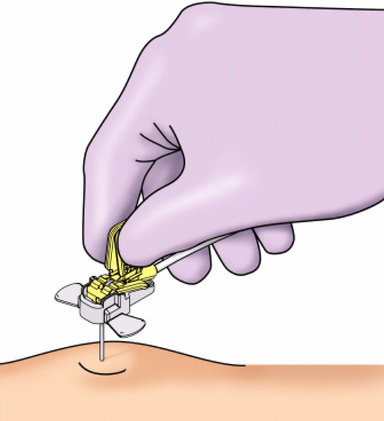

• The implanted venous access device is percutaneously accessed with a noncoring needle.

• The use of a noncoring needle allows for repeated access of the venous device without damage to the silicone core.

• The noncoring needle chosen should be of optimal length, with the most common length for adults 1½ or 1¾ inches. Patients with increased subcutaneous tissue may need a longer needle for access. Too short a needle may cause the flanges to press against the skin surrounding the portal chamber, leading to patient discomfort and possibly resulting in damage to the skin overlying the venous access device. Too long a needle may result in a rocking motion that can cause discomfort, possible migration out of the portal septum, or damage to the integrity of the septum, impairing it for further use.

EQUIPMENT

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Assess patient and family readiness to learn and identify factors that affect learning.  Rationale: Assessment allows the nurse to individualize teaching and maximize understanding.

Rationale: Assessment allows the nurse to individualize teaching and maximize understanding.

• Provide information about the implantable venous access device and the methods used for accessing it.  Rationale: Information assists the patient and family in understanding the procedure and decreases patient and family anxiety.

Rationale: Information assists the patient and family in understanding the procedure and decreases patient and family anxiety.

• Explain the patient’s role during the procedure and expected outcomes.  Rationale: The patient is able to participate in care, and cooperation is encouraged.

Rationale: The patient is able to participate in care, and cooperation is encouraged.

• Explain the anticipated sensations during the access procedure.  Rationale: Explanation allows the patient to alert the healthcare provider to unusual or unexpected sensations during the procedure.

Rationale: Explanation allows the patient to alert the healthcare provider to unusual or unexpected sensations during the procedure.

• Explain site care and signs and symptoms of infection and infiltration.  Rationale: Explanation enables the patient and family to participate in care, and the patient is encouraged to report untoward events to healthcare providers.

Rationale: Explanation enables the patient and family to participate in care, and the patient is encouraged to report untoward events to healthcare providers.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Review the patient’s medical history specifically related to problems with device implantation, complications with previous access, and allergies to antiseptic solutions.  Rationale: Baseline data are provided.

Rationale: Baseline data are provided.

• Obtain the patient’s vital signs.  Rationale: Baseline data are provided.

Rationale: Baseline data are provided.

• Review the patient’s current laboratory status, including coagulation results.  Rationale: Baseline coagulation studies are helpful in determination of the risk for bleeding. If results are abnormal, consult with the primary care provider before accessing the device.2

Rationale: Baseline coagulation studies are helpful in determination of the risk for bleeding. If results are abnormal, consult with the primary care provider before accessing the device.2

Patient Preparation

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Ensure that the patient and family understand preprocedural teaching. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

• Assist the patient to a supine position with the head of the bed elevated up to a 30-degree angle.  Rationale: Positioning prepares the patient and allows optimal access to the implanted venous access device.

Rationale: Positioning prepares the patient and allows optimal access to the implanted venous access device.

References

![]() 1. Barton, JC, Poon, MC. Coagulation testing of Hickman catheter blood in patients with acute leukemia. Arch Intern Med. 1986; 146(11):2165–2169.

1. Barton, JC, Poon, MC. Coagulation testing of Hickman catheter blood in patients with acute leukemia. Arch Intern Med. 1986; 146(11):2165–2169.

![]() 2. Beck, SL, et al. Standards of care for the patient with a venous access device. Salt Lake City, UT: American Cancer Society, Utah Division; 1990.

2. Beck, SL, et al. Standards of care for the patient with a venous access device. Salt Lake City, UT: American Cancer Society, Utah Division; 1990.

3. Camp, Sorrell, D, Accessing and Deaccessing Ports. Where is the evidence. Clin Jour of Oncol Nurs 2009; 13:587–590.

![]() 4. CDC. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter related bloodstream infection. MMWR. 2002; 5:1–26.

4. CDC. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter related bloodstream infection. MMWR. 2002; 5:1–26.

![]() 5. Deltec, Incorporated, Clinician information Port-A-Cath®, Port-A-Cath II and P. A. S. Port systems,. Deltec Incorporated, St Paul, MN, 2002:1–24. [Deltec, Inc].

5. Deltec, Incorporated, Clinician information Port-A-Cath®, Port-A-Cath II and P. A. S. Port systems,. Deltec Incorporated, St Paul, MN, 2002:1–24. [Deltec, Inc].

![]() 6. Frey, AM, Drawing blood from vascular access devices. J Infusion Nurs 2003; 26:285–293.

6. Frey, AM, Drawing blood from vascular access devices. J Infusion Nurs 2003; 26:285–293.

7. Hartkopf, L. Implanted Ports, computed tomography, power injectors, and catheter rupture. Clin J of Oncol Nurs. 2008; 12:809812.

![]() 8. Himberger, J, Himberger, L. Accuracy of drawing blood through infusing intravenous lines. Heart Lung. 2001; 30:66–73.

8. Himberger, J, Himberger, L. Accuracy of drawing blood through infusing intravenous lines. Heart Lung. 2001; 30:66–73.

9. Infusion Nurses Society. Infusion nursing standards of practice. J Infus Nurs. 2006; 29:S1–S92.

10. Infusion Nurses Society. Policies and procedures for infusion nursing, ed 3. Norwood, MA: Author INS; 2006,.

11. Johnson, K. Power injectable portal systems. J of Radiol Nurs. 2009; 28:27–31.

![]() 12. Mayo, DJ, Dimond, EP, Framer, W, et al. Discard volumes necessary for clinically useful coagulations studies from heparinized Hickman catheters. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1996; 23(4):671–675.

12. Mayo, DJ, Dimond, EP, Framer, W, et al. Discard volumes necessary for clinically useful coagulations studies from heparinized Hickman catheters. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1996; 23(4):671–675.

![]() 13. Polovich, M, Whitford, J, Olsen M: Oncology Nurses Society. Chemotherapy and biotherapy guidelines and recommendations for practice, ed 3. Pittsburgh: Oncology Nursing Press, Inc; 2009.

13. Polovich, M, Whitford, J, Olsen M: Oncology Nurses Society. Chemotherapy and biotherapy guidelines and recommendations for practice, ed 3. Pittsburgh: Oncology Nursing Press, Inc; 2009.

![]() 14. Pinto, KM. Accuracy of coagulation values obtained from a heparinized central venous catheter. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1994; 21(3):573–575.

14. Pinto, KM. Accuracy of coagulation values obtained from a heparinized central venous catheter. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1994; 21(3):573–575.

15. Schummer, W, Schummer, C, Schelenz, C, Case Report. The malfunction of implanted venous access devices. Brit J of Nurs. 2009; 12(4):210–214.

![]() 16. Yucha, C, DeAngelo, E, The minimum discard volume. J Intraven Nurs 1996; 19:141–146.

16. Yucha, C, DeAngelo, E, The minimum discard volume. J Intraven Nurs 1996; 19:141–146.

Camp-Sorrell, D, Mermel, L, Kluger, D, et al, The efficacy of chlorhexidine-impregnated sponge (BioPatch) for the prevention of intravascular catheter related infection. a prospective, randomized, controlled multi-center trial. abstract of the 40th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2000:422.

Rosenthal, K, Pinpointing intravascular device complications. Nurs Manage, 2003:37–42. [June].

Sabel, M, Smith, J, Principles of chronic venous access. recommendations based on the Roswell Park experience. Surg Oncol 1988; 6:171–177.

Seemann, S, Reinhardt, A. Blood sample collection from a -peripheral catheter system compared with phlebotomy. -J Intraven Nurs. 2000; 23:290–297.

Sterba, K. Controversial issues in the care and maintenance -of vascular access devices in the long-term/subacute care client. J Infus Nurs. 2001; 24:249–254.

Wu P-y, Yeh Y-C, Huang C-H, et al. Spontaneous migration of a Port-A-Cath catheter into ipsilateral jugular vein in two patients with severe cough. Ann Vasc Surg. 2005; 19:734–736.